1. Introduction

In recent decades, the progressive recolonization of the wolf (

Canis lupus italicus) along the Apennine and Pre-Alpine regions of Italy has been recognized as a conservation success. However, this recovery has also intensified conflicts with extensive and semi-extensive livestock farming systems, primarily due to increased predation on free-ranging livestock [

1,

2]. These interactions compromise not only the economic viability of livestock enterprises but also the resilience of local socio-ecological systems and the continuity of traditional pastoral practices, which are integral to the cultural identity and ecological integrity of mountain landscapes [

3].

Extensive and semi-extensive livestock systems warrant protection, as they can contribute positively to biodiversity conservation when managed appropriately, and they hold substantial socio-cultural value. Nevertheless, the demographic and spatial expansion of wolf populations has introduced new management challenges, particularly in relation to livestock protection and the development of effective coexistence strategies between large carnivores and rural communities [

4].

Across the EU, wolf range expansion has coincided with higher livestock depredation. In a baseline period 2012–2016, member-state reporting averaged ≈19,500 sheep killed per year (sample of EU countries). In 2020–2022, broader reporting across species indicates ≈65,000 livestock killed annually. In Italy, the sheep-and-goat sector contracted sharply: active ovicaprine farms fell by ~20% between 2019 and 2023, reaching 112,385 by December 2023—nearly 20,000 fewer in just one year [

5,

6].

Canis lupus is currently classified as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List (2023), and its protection is supported by robust international and European legislative frameworks that recognize its critical ecological role [

7]. The Bern Convention (1979) and CITES regulate habitat protection and wildlife trade, respectively [

8,

9]. At the European level, the Habitats Directive (92/43/EEC) [

10] promotes the conservation of the species, while EU funding mechanisms—particularly the LIFE Program—support concrete conservation and conflict mitigation initiatives [

11,

12].

Livestock protection is most effective when built as an integrated, context-specific system. Core tools include fencing (fixed, mobile, and especially electrified), continuous human presence (e.g., shepherding/range riding), and livestock-guarding or herding dogs. Electric or reinforced fences are highly effective in sensitive phases (lambing, night corrals) but only when construction and maintenance standards are sustained [

13].

Active human presence remains a strong deterrent by enabling immediate response and tight stock control; where continuous presence is impractical, operators increasingly pair scheduled checks with trained livestock-guarding dogs (LGDs). Properly socialized LGDs—such as the Italian Maremmano-Abruzzese—reduce depredation primarily through behavioral disruption (barking, patrolling, scent-marking, body blocking) and by creating a “landscape of fear” that alters predator space-use rather than eliminating predators [

14].

To frame deterrents conceptually, ethology distinguishes primary (chronic, non-contingent) versus secondary (reactive, cue-triggered) anti-predator defenses. Primary defenses include traits or habits like crypsis or nocturnality; secondary defenses include vigilance, alarm calls, flight, or freezing in response to odors, sounds, or motion cues [

15].

Applied to conflict mitigation, Shivik et al. categorize artificial tools as aversive repellents (e.g., chemical/olfactory or shock-based) versus behavior-contingent disruptive devices (e.g., radio-activated guards, responsive lights/sirens). Field trials in Wisconsin showed that behavior-contingent devices reduced carcass use relative to fladry controls. Fladry can work, but effectiveness typically wanes after weeks to a few months if animals habituate [

16].

North American work by Dalniel Kinka and Julie Young adds operational guidance: LGDs consistently cut losses across settings; effectiveness improves with training, stock bonding, and coverage; and deterrents that adapt to animal behavior (e.g., radio-triggered/human-activated systems, robotics) persist longer than static devices [

17].

Many prey species (e.g.,

Capreolus capreolus, Cervus elaphus, Dama dama) exhibit behavioral and physiological adaptations for predator detection and avoidance, particularly through olfactory cues. Exposure to carnivore-derived substances (urine, feces, scent gland secretions, or fur) can suppress non-defensive behaviors (e.g., feeding, grooming) and prompt relocation to perceived safer areas—offering potential applications in agro-pastoral protection [

18].

In the field of bioacoustics, Götz and Janik (2013) [

19] evaluated Acoustic Deterrent Devices (ADDs) for protecting aquaculture from pinniped predation, identifying challenges such as habituation, environmental noise interference, and potential auditory harm to both target and non-target species.

In Europe, experimental efforts have led to the development of portable deterrent prototypes, including the anti-wolf collar patented by Pietro Orlando (Patent No. 202019000003221, issued 22/02/2022 by the Italian Ministry of Economic Development – Patent and Trademark Office). This solar-powered, durable acoustic device emits modulated frequencies and represents a promising innovation for reducing predation and fostering coexistence between humans and wildlife.

Scientific literature increasingly supports the use of non-lethal technologies to mitigate conflicts between large carnivores and human activities, particularly in livestock farming [

20,

21]. A range of deterrents—acoustic, visual, electric, and chemical—have been tested with varying degrees of success depending on ecological and social context. However, the use of acoustic collars specifically targeting predators remains underexplored, especially in Mediterranean ecosystems.

Designing acoustic deterrents requires matching signals to each species’ hearing. Gray wolves perceive high frequencies (documented responses ≥20–30 kHz and, by canid analogy, up to ~45 kHz), while domestic dogs typically hear ~63 Hz–45–47 kHz. In contrast, common livestock hear less of the ultrasonic band: sheep ≈100 Hz–30 kHz, goats ≈78 Hz–37 kHz, and cattle ≈23 Hz–35–37 kHz. These differences enable targeted, high-frequency cues that are salient to wolves (and to dogs) but less audible to most livestock—provided output levels are controlled, and habituation is managed. Note that audibility ≠ aversion: field tests show some large mammals (including wolves) do not consistently avoid all ultrasonic signals; effectiveness improves with modulation (changing pitch or loudness over time) and with context-appropriate deployment [

22].

Table 1.

Comparative Auditory Capabilities and Functional Adaptations in Wolves, Dogs, and Livestock: Implications for Acoustic-Based Management Strategies.

Table 1.

Comparative Auditory Capabilities and Functional Adaptations in Wolves, Dogs, and Livestock: Implications for Acoustic-Based Management Strategies.

Feature /

Parameter |

Wolf (Canis lupus) |

Dog (Canis lupus

familiaris) |

Livestock (sheep, goats, cattle, horses) |

| Hearing range (Hz) |

~150–45,000 Hz (up to ~80,000 Hz in some sources) |

~67–45,000 Hz |

~23–40,000 Hz, depending on species |

| Peak sensitivity (Hz) |

~2,000–8,000 Hz (behaviorally); ~40,000–80,000 Hz (physiologically) |

~2,000–8,000 Hz (behaviorally); ~1,000–20,000 Hz |

~8,000–10,000 Hz (sheep/goats: ~10 kHz; cattle: ~8 kHz); ~1,000–8,000 Hz |

| Ultrasound detection |

Excellent; highly sensitive to ultrasonic range (up to 80 kHz) |

High; upper limit ~60 kHz |

Poor above ~20 kHz; limited response near 30–40 kHz |

| Sensitivity level |

Very high; adapted for long-distance detection and hunting |

High, but variable across breed, age, and training |

Moderate; suited to mid-frequency group alertness |

| Communication frequencies |

~150–780 Hz (howls) with higher harmonics |

Wide repertoire: barking, whining, growling |

Mostly low-frequency vocalizations: bleats, moos, neighs |

| Functional implication |

Detection of prey, predators, and conspecific calls; social communication |

Responsive to human cues and high-frequency commands |

Adapted for herd alertness; limited reliance on high-frequency acoustic signals |

| Adaptation |

Wild hunter: optimized for survival, navigation, and territorial vocalizations |

Domestic adaptation: tuned to canine–human communication |

Domesticated herd species: optimized for inter-individual contact and predator detection |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

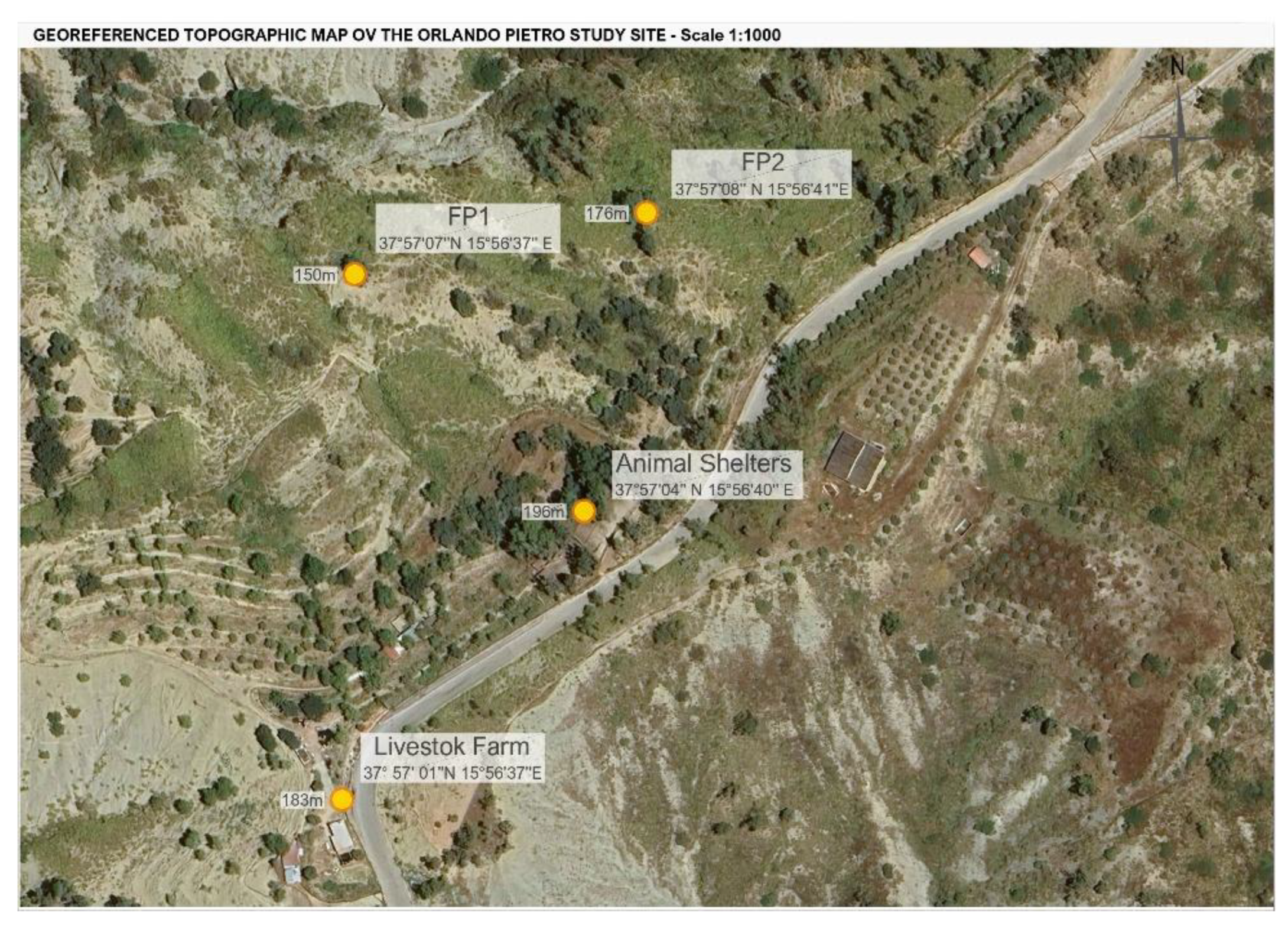

The field trial evaluating the effectiveness of the wolf deterrent collar was conducted from June to August 2024 at the Orlando Pietro farm, located in Contrada Vutumà, Bova Marina (Reggio Calabria), southern Italy, at an elevation of 200 meters above sea level (37°57′01″ N, 15°56′37″ E) [

23]. This site lies within a designated disadvantaged area under national and European Union rural development frameworks and is situated in the hilly Mediterranean landscape of the Grecanic zone of Calabria [

24]. The region experiences a typical Mediterranean climate, characterized by hot, arid summers and mild, wet winters. Annual average temperatures range from 9 °C to 31 °C, with mean annual precipitation of approximately 545 mm, predominantly occurring during the winter months. Seasonal variations in climatic parameters such as wind speed and relative humidity may influence the operational efficacy of acoustic deterrent systems (

Appendix A,

Table A1 for detailed climatic data).

2.2. Experimental Design

The trial was conducted on a cohort of 150 goats of Aspromonte (Capra dell’Aspromonte), an autochthonous breed well adapted to the mountainous and semi-arid environments of the southern Apennines, known for its hardiness and aptitude for extensive grazing. The animals were stratified into three homogeneous groups of 50 individuals each, balanced by age class—9 juveniles (<1 year), 10 primiparous and secondiparous (1–3 years), and 31 multiparous (>3 years); by sex (2 males and 48 females); and by physiological status—8 non-pregnant, 10 pregnant, and 30 lactating individuals. This stratification was designed to control for potential behavioural and physiological variability that could influence experimental outcomes. Each group was assigned to a separate 10-hectare paddock to ensure mutual isolation and was allowed to graze simultaneously during the months of June, July, and August 2024. Animal management adhered strictly to current animal welfare regulations, ensuring minimal stress. All individuals were identified in the National Database (B.D.N.) using ear tags and ruminal boluses registered to Azienda Agricola Orlando Pietro [

25].

The three experimental groups were subjected to distinct grazing management strategies:

SO: Grazing under the supervision of an experienced herder only.

SGD: Grazing with an experienced herder and livestock guardian dogs (Canis lupus familiaris, Maremmano-Abruzzese breed), recognized for their effectiveness in predator deterrence.

SGDC: Grazing with a herder, guardian dogs, and the application of an acoustic wolf-deterrent collar.

These management strategies were compared to evaluate their relative effectiveness in mitigating wolf predation, providing a basis for assessing the impact of integrated livestock protection measures.

2.3. Wolf-Deterrent Collar

The prototype wolf-deterrent collar (

Figure 1) was developed using additive manufacturing (3D printing) techniques, employing a high-performance technical plastic filament characterized by elevated mechanical and thermal resistance. A wood-like coloration was selected for its low thermal conductivity, minimizing the risk of overheating under direct solar exposure. The collar was ergonomically designed through digital modelling to accommodate three primary functional components: (i) two piezoelectric speakers (POFET model, 30 Vp-p, 2.5 Hz–60 kHz), (ii) a Kemo M048N frequency generator module, adjustable between 7 and 40 kHz, capable of producing a maximum estimated sound pressure level of 110 dB at a distance of 1 meter, and (iii) a 12V (1.5 W) photovoltaic panel connected to a 150 Ah rechargeable lithium-ion battery. This configuration ensures operational autonomy for up to four days in the absence of direct sunlight (see

Table 2 for technical specifications).

The entire system was integrated into a collar structure designed to meet IP65 standards for environmental protection, while maintaining lightweight and dynamic functionality suitable for use in extensive livestock systems.

The device emits short phrases of modulated tones built from natural harmonic intervals documented in the local bagpipe tradition. Supplementary materials: (Video S1: Wolf-Bagpipe

https://youtu.be/wVHFM7lb7kM ). These phrases sweep through a set of discrete fundamentals between 105 Hz and 1,200 Hz, using gentle amplitude (loudness) and frequency (pitch) modulation to create organic, non-monotonic cues. The specific fundamentals (ascending) are: 105, 204, 219.766, 247.237, 274.707, 298, 302.178, 329.649, 386, 412.061, 439.473, 439.532, 471, 494.473, 549.415, 551, 604.357, 628, 659.298, 702, 773, 841, 847, 906, 969, 1,030, 1,088, 1,145, and 1,200 Hz [

26]. These non-periodically sequenced, harmonically grounded intervals are broadcast by the wolf-deterrent collar to increase salience and reduce habituation.

Under open-field conditions with minimal physical obstructions, the acoustic range of the deterrent collar was estimated to span between 50 and 100 meters, corresponding to a coverage area of approximately 7,850 to 31,400 m

2. This variability is influenced by local topographic and meteorological conditions, consistent with findings by Götz and Janik (2013) on terrestrial acoustic signal propagation [

19]. The collar’s design and cost-efficiency make it a viable and economically accessible solution for small-scale livestock farms operating in mountainous regions with elevated predation pressure. As such, it supports the development of sustainable coexistence strategies between extensive livestock production and wildlife conservation.

2.4. Retrospective and Progressive Data Comparison and Analysis

To evaluate the impact of wolf predation on goat farming, a retrospective analysis was conducted at Azienda Agricola Orlando Pietro between 2020 and 2024, to document the historical occurrence of wolf attacks in the area. Concurrently, the study assessed the effectiveness of the wolf-deterrent acoustic collar by comparing predation rates across three experimental groups (SO, SGC, and SGDC) during the field trial, thereby quantifying the device’s ability to reduce predation events. In parallel, health and welfare indicators of the collared goats were continuously monitored to detect any potential adverse effects associated with the device’s use.

Throughout the experimental period, each group was systematically monitored through direct visual inspections and ethological observations to document wolf–goat interactions. Observers recorded complete predation sequences, including stealthy approaches along vegetative cover, prolonged herd surveillance from a distance, and pursuit behaviors targeting isolated or vulnerable individuals. Both successful and unsuccessful predation attempts were meticulously documented, generating a comprehensive behavioral dataset.

The behavioral and predation data were then analyzed to assess the relative effectiveness of the acoustic collar compared with traditional livestock protection measures. This comparative assessment followed the methodological framework proposed by Boitani (2003) and commonly applied in human–predator conflict studies [

27].

2.5. Camera Trapping

To confirm and monitor predator presence in the study area, two digital camera traps were installed approximately 100 meters from the livestock shelter (

Figure 2), strategically positioned to maximize the likelihood of capturing high-resolution images and videos of wildlife. The camera traps were positioned within the boundaries of the plots in order to monitor the three study areas.

The camera traps (CT1 and CT2) used were Spypoint Flex-M Trail models, equipped with pre-activated SIM cards enabling real-time data transmission and continuous capture technology for constant monitoring [

28]. These devices feature a detection radius of 27 meters and a trigger speed of 0.4 seconds, effectively documenting animal movement without disturbing natural behavior [

29]. Camera traps operate in colour during the day and switch to black-and-white mode at night, using low-impact infrared illumination, and are securely mounted to trees with straps to ensure stability and security behavior [

30].

2.6. Milk Production

Milk production was monitored during late lactation over a fixed two-month window (1 June–31 July 2024). Animals were stratified into three homogeneous groups of 50 individuals each: Smart Guard Dog Collar (SGDC), Shepherding with Guard Dogs (SGD), and Shepherding Only (SO). Each group was balanced by age class (9 juveniles <1 year, 10 primiparous or secondiparous 1–3 years, 31 multiparous >3 years), sex (2 males, 48 females), and physiological status (8 non-pregnant, 10 pregnant, 30 lactating). Milking occurred once daily following the farm’s routine. Group-level milk volume was measured at each milking with calibrated meters (±1 percent accuracy) and logged immediately after collection. For each group, average daily milk yield was computed as the mean of the daily volumes over the 62-day monitoring period. Husbandry, feeding, and watering were kept constant across groups [

31]

.

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficacy of Combined Protective Strategies

It is expected that a combination of traditional protection strategies and the benefit of the acoustic collar not only enhances herd protection through predator deterrence but also, the well-being of the herd and improvement in milk yield via stress reduction.

In the control group (SO), which relied solely on human supervision, the highest rates of predation and livestock mortality were recorded. These findings align with previous research indicating that human presence alone is often insufficient to deter wolf attacks, particularly in topographically complex environments that facilitate predator ambush and escape.

In contrast, the second group (SGD), where herds were guarded by an experienced herder supported by livestock guardian dogs, experienced a 26.39% reduction in wolf attacks and a significant decrease in predation-related mortality to 1.49%. These results support existing literature on the effectiveness of guardian dogs in mitigating conflicts with large carnivores. However, the persistence of sporadic predation events suggests that dogs alone may not provide complete protection, especially under sustained predation pressure.

The highest level of protection was observed in the third group (SGDC), which combined an experienced herder, guardian dogs, and a sentinel goat equipped with an anti-wolf acoustic collar. No predation events were recorded in this group despite confirmed wolf activity. The collar’s acoustic deterrent appears to work synergistically with the defensive behavior of guardian dogs, enhancing overall herd protection.

The device’s effective coverage range of anti-wolf collar contributed to the absence of predation across all SGDC farms during the monitoring period (June–July 2025). Further longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate its long-term efficacy across diverse ecological and management contexts.

The collar’s modulated, natural-harmonic sound patterns may help slow habituation—a common limitation of repetitive acoustic stimuli—but current evidence is limited to a single ~3-month field trial and does not demonstrate prevention of habituation. These patterns are also designed to minimize stress in domestic livestock, consistent with research on ethologically compatible auditory cues.

Based on field observations, dogs show no reaction to noise, suggesting that it does not cause them fear

Camera trap data confirmed continuous wolf presence across all experimental groups, underscoring the high and persistent predation pressure. These findings highlight the urgent need for effective livestock protection strategies, as mortality rates can reach critical thresholds without adequate preventive measures.

Beyond reducing predation, the SGDC group, according to the shepherds this group also showed improved productive performance, with an average daily milk yield of 30 L—15.38% higher than the 26 L recorded in the SO and SGD groups. This increase is plausibly linked to reduced stress levels due to the absence of predation, consistent with studies connecting lower environmental stress to enhanced milk production and animal welfare in small ruminants [

32]. Also, neither signs of acoustic-induced stress were observed in the livestock nor the dogs, such as escape attempts, altered feeding, or disrupted social interactions, behaviours that, according to other studies, indicate negative impact on animal welfare [

33].

4.2. Environmental Influences on Acoustic Deterrent Performance

The propagation of sound in atmospheric environments is governed by several physical parameters, including relative humidity, temperature, atmospheric pressure, and wind dynamics [

34,

35]. Among these, relative humidity plays a particularly critical role in modulating the absorption of high-frequency sound. Elevated humidity levels reduce acoustic attenuation—especially within the 2–8 kHz frequency range commonly employed in wildlife deterrent systems—thereby extending the effective transmission range of acoustic signals [

19,

36]. This effect is especially advantageous during nocturnal periods and in autumnal conditions, when ambient humidity tends to be higher.

Wind conditions also exert a significant influence on sound propagation. Favorable wind directions can enhance signal transmission by refracting sound waves along the wind path, whereas adverse or turbulent wind conditions may deflect sound trajectories or diminish sound pressure levels, thereby reducing the efficacy of deterrent systems [

37].

Temperature gradients, particularly vertical thermal inversions—frequently occurring during evening and nighttime in mountainous regions—can further enhance lateral sound propagation through refraction, effectively expanding the acoustic coverage area [

38]. These findings highlight the necessity of incorporating local topographic and meteorological variability into the design, calibration, and spatial deployment of acoustic deterrent devices. In complex terrains such as hilly or mountainous landscapes, where atmospheric dynamics are highly variable, site-specific acoustic performance assessments and adaptive calibration protocols are essential to ensure consistent operational effectiveness [

19].

These environmental factors are particularly relevant for interpreting the results of this study and for assessing the potential application of the collars in different regions. Variations in humidity, wind, and temperature regimes may lead to differences in deterrent effectiveness, indicating that results obtained under Mediterranean conditions cannot be directly extrapolated to drier continental or alpine contexts. Therefore, site-specific trials and calibration are essential to validate the broader applicability of acoustic collars and to ensure consistent performance across diverse ecological and climatic scenarios.

4.3. Perspectives and Work in Progress

As part of an ongoing pilot study aimed at testing innovative non-lethal tools for predator deterrence, three ovicaprine farms located within the Aspromonte National Park, in the province of Reggio Calabria (Southern Italy), were selected for the deployment of anti-wolf collars. Each farm—Romeo Carmelo (Bova), Romeo Giuseppe (Bova/Roghudi), and Stelitano Domenico (Bova Marina/Bova)—was equipped with three acoustic Anti-predation collars on June 3rd, 2025. All farms were in the transhumance period during the monitoring phase and managed approximately 150 goats and 150 sheep each.

From June 3rd to the present (late October 2025), no predation events or livestock losses attributable to wolves have been reported. While preliminary, these results indicate a potential deterrent effect of the device against wolf attacks in extensive grazing systems. Continued monitoring and an expanded sample size will be necessary to confirm these findings and evaluate long-term effectiveness under diverse ecological and management conditions.

Moreover, this deterrent supports the practice of transhumance, recognized by UNESCO (2019) as intangible cultural heritage, representing not only an ancient tradition but also a sustainable land management model [

39]. Its value lies in combining biodiversity conservation with the maintenance of traditional knowledge and cultural landscapes, offering significant insights for developing pastoral practices compatible with environmental protection and coexistence with wildlife.

For future studies, an environmental impact assessment of the anti-wolf collar is proposed across all scientific fields to safeguard the environment and ensure sustainable development [

40], and to validate this deterrent in contexts beyond the Mediterranean region.