1. Introduction

Fatal dog attacks represent a serious concern for public health, forensic medicine, and legal policy. Globally, dog bites are among the most frequent animal-related injuries, with the United States reporting approximately 4.5 million incidents annually, including 885,000 requiring medical attention and an average of 20 fatalities per year. While the U.S. benefits from robust epidemiological tracking systems such as DogsBite.org, the European context, and Italy in particular, remains underrepresented in systematic data collection and analysis [

1]. A systematic review by Giovannini et al. (2023) [

2] examined the medico-legal implications of canine aggression on an international scale. In Italy, the only national epidemiological study on fatal dog attacks in Italy was conducted by Ciceroni and Gostinicchi, covering the period from 1984 to 2009 [

3]. Their work offered a foundational profile of victims, breeds involved, and environmental contexts, but left a significant gap in longitudinal surveillance. Since then, Italian literature has focused primarily on ethological, behavioral, and forensic aspects [

4], without updating the epidemiological framework.

In response to rising public concern, the Italian Ministry of Health in 2003 issued an Ordinance (the so called Sirchia Ordinance), renewed in 2004, which imposed breed-specific restrictions and mandated the use of leashes and muzzles for dogs deemed dangerous [

5]. However, this approach was replaced in 2009 by a new ordinance emphasizing owner accountability and behavioral risk reporting, eliminating the breed list altogether [

6]. Despite these regulatory shifts, no national registry or centralized database has been established to monitor fatal dog attacks or behavioral risk factors.

Recent forensic studies have highlighted the complexity of canine aggression. Pomara et al. (2011) [

7] demonstrated the utility of bite mark analysis in pack attacks, and more recently, Giovannini et al. (2025) [

8] expanded this approach through a morphometric study that improved the reliability of lesion-to-weapon correlations and the interpretation of bite mark patterns in forensic investigations.

Iarussi et al. (2020) [

9] proposed a novel forensic method for identifying aggressive dogs via human DNA traces in the oral cavity. Benevento

et al. (2021) further emphasized the need for multidisciplinary collaboration between forensic medicine and veterinary science [

10]. In this context, Roccaro et al. (2021) provided an additional perspective by applying forensic genetics to identify the species or individual animal responsible for an attack, demonstrating the potential of molecular methods in complex medico-legal cases [

11]. Giovannini et al. (2023) [

2] conducted a systematic review of over 100 studies on the medico-legal implications of dog bites, underscoring the fragmented nature of current research and the absence of comprehensive epidemiological data.

In contrast, the United States maintains a publicly accessible database that tracks fatal dog attacks across multiple variables—including breed, ownership, victim age, and environmental context—enabling real-time surveillance and policy evaluation. Between 2020 and 2023, DogsBite.org recorded an average of 55–63 fatalities annually, with pit bulls involved in over 60% of multi-dog attacks and children under 9 and adults over 30 comprising the majority of victims [

12]. This model offers a valuable reference for Italy, where the lack of centralized data continues to hinder effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Given this context, the present study aims to fill the epidemiological gap by providing a systematic and updated analysis of fatal dog attacks in Italy from 2009 to 2025. Building upon the methodology of Ciceroni and Gostinicchi [

3], this research extends the observation window and incorporates multivariate statistical analysis to identify trends in victim demographics, breed involvement, ownership status, and environmental settings. The ultimate goal is to inform public health policy, enhance forensic protocols, and advocate for the creation of a national behavioral risk registry modeled on international best practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Selection

This study examined fatal dog attacks in Italy during the period 2009–2025 by systematically collecting data from national journalistic sources. The main newspapers consulted included Il Corriere della Sera, La Repubblica, and Il Messaggero, along with additional coverage from La Stampa, Il Mattino, and Il Corriere del Mezzogiorno. Additional details were also obtained from local news outlets covering the specific areas where the attacks occurred.

The search was conducted using the digital archives of these outlets, employing keywords such as “dead,” “mauled,” “attack,” “dog,” and “bite.” The investigation was performed year by year, beginning with the events of 2009 and continuing through 2025. Detailed case-level information, including date, location, victim demographics, dog breed, ownership status, and environmental context, is available in

Table S1 (S1-Supplementary Materials). Verified data from each report were extracted and summarized to support the analyses described below. A supporting appendix accompanies the analysis, providing a complete chronological account of the incidents along with references to the primary sources consulted (

S2- Supplementary Materials).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included cases met the following criteria:

- -

The fatality was directly attributable to the dog attack, whether occurring at the scene or later in hospital due to related complications (e.g., sepsis).

- -

The attacking dog(s) were identified and confirmed.

- -

The incident occurred within Italian territory.

- -

The report was corroborated by multiple independent sources.

Excluded cases involved:

- -

Unconfirmed cause of death.

- -

Unverified dog involvement.

- -

Single-source reports.

- -

Incidents outside Italy.

2.3. Definition of Study Variables

For each incident included in the analysis, data were collected on key epidemiological variables. These included the date (year and month) and location (province) of the event, as well as demographic details of the victims, such as age, sex, and number. Information was also gathered on the dogs involved, including their number, breed (or morphological/functional type), and ownership status—whether the animals belonged to the victim, to third parties, or were free-roaming or stray. Particular attention was paid to the number of dogs implicated in each attack, noting whether the aggression was carried out by a single dog, two dogs, or more than two dogs, the latter being classified as a pack attack. The environmental context in which the attack occurred was categorized, distinguishing between domestic settings, private gardens, public urban areas, and rural spaces. The database structure was designed to mirror that of the earlier study by Ciceroni and Gostinicchi (2009), thereby enabling direct comparisons with the cases documented between 1984 and 2009.

2.4. Data Analysis and Bias Control Strategies

The data collected were compiled into a structured database designed for both descriptive and exploratory statistical analysis, with the objective of identifying temporal trends, recurring characteristics, and potential risk factors associated with fatal dog attacks.

To ensure methodological rigor and minimize interpretative bias, several control strategies were implemented. Only incidents confirmed by at least two independent journalistic sources were included in the dataset. All available information was cross-verified to ensure narrative consistency and data reliability. Ambiguous or unverified cases were systematically excluded in order to preserve the accuracy and credibility of the analysis.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and proportions were calculated for categorical variables. Measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation, IQR) were computed for continuous variables such as victim age. Visualizations included bar charts, heatmaps, and stacked plots.

Inferential Analysis was performed as listed below:

- -

Chi-square tests were used to assess independence and goodness-of-fit across sex, age groups, geographic regions, and ownership categories.

- -

Binary logistic regression modeled the likelihood of attacks occurring in private vs. public settings, using predictors such as victim age, breed type, and ownership status.

- -

Multinomial logistic regression explored associations between victim age groups and dog ownership categories.

- -

Poisson regression assessed temporal trends in annual fatality counts, adjusting for potential overdispersion.

- -

Interaction effects were tested between age and environment, and breed type and ownership, to identify compound risk factors.

Model diagnostics included Hosmer-Lemeshow tests, AIC/BIC comparisons, and residual analysis. All statistical procedures were conducted using JASP (v0.18.3) and R (v4.3.1), with supplementary processing in Microsoft Excel.

4. Discussion

The present study offers a unique opportunity to examine the phenomenon of fatal dog attacks in Italy across two distinct timeframes governed by different regulatory strategies. The first period (1984–2009) was characterized by breed-specific preventive measures, while the second (2009–2025) marked a shift toward owner accountability and the behavioral assessment of individual animals [

3,

5,

6]. Despite this regulatory evolution, the annual number of fatal attacks rose from 1.28 to 3.18 cases per year, with a notable increase observed in the most recent five-year interval. These findings raise concerns about the practical effectiveness of a prevention model based solely on individual responsibility.

The increase in fatal incidents is likely driven by multiple contributing factors rather than a single cause. According to data from the National Canine Registry, the dog population in Italy has more than doubled over the past decade [

13,

14].

It is therefore plausible that the rising frequency of human–dog interactions has contributed to a higher absolute risk of fatal attacks. However, this interpretation should be considered alongside additional behavioral, management, and environmental determinants emerging from detailed case analyses.

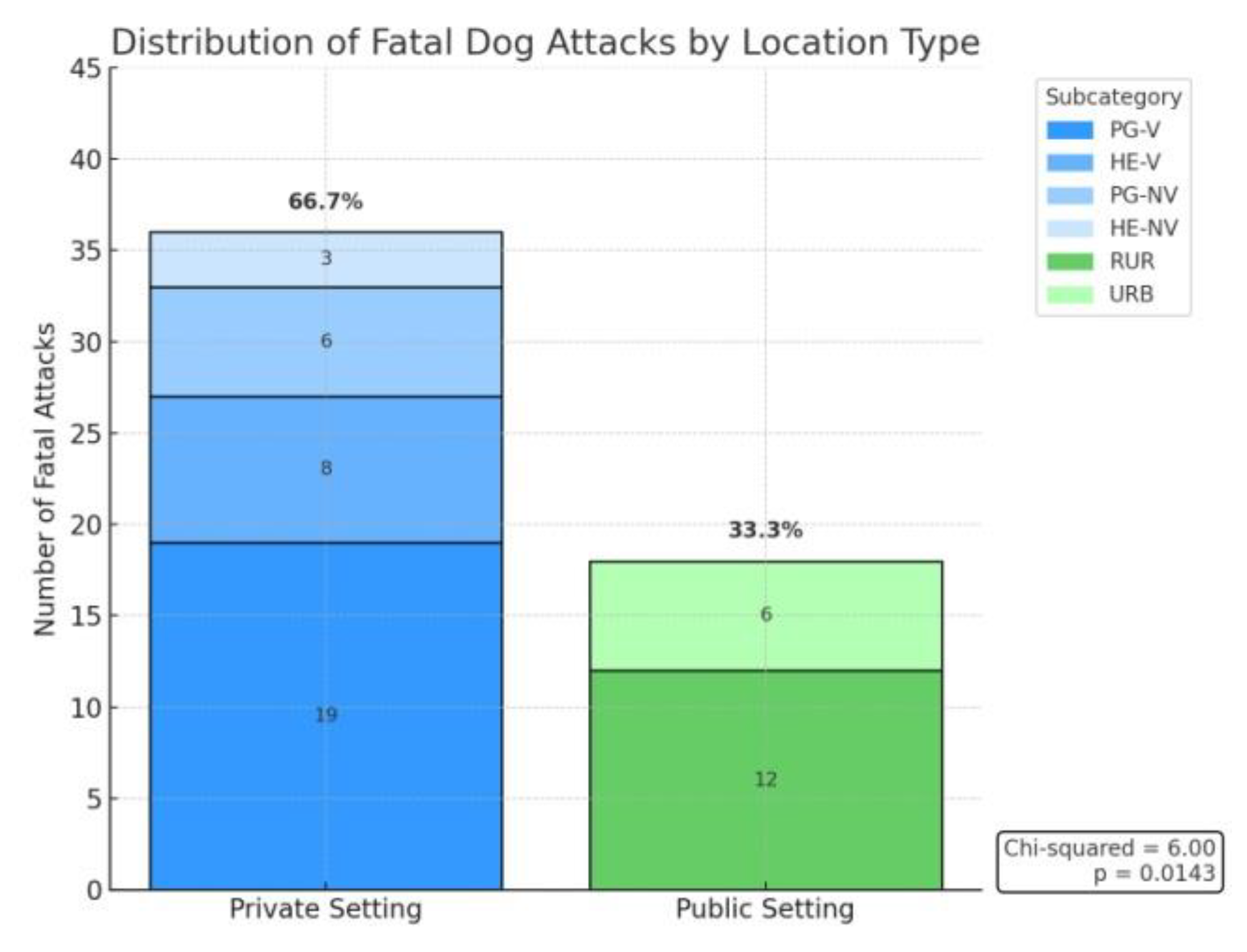

From an environmental perspective, 66.7% of attacks occurred in private settings, particularly within the victim’s home or garden. Although this could suggest a lifestyle shift toward closer domestic cohabitation, comparison with the 1984–2009 data reveals that private spaces have consistently represented the primary context of fatal attacks, suggesting a structural pattern rather than a recent trend.

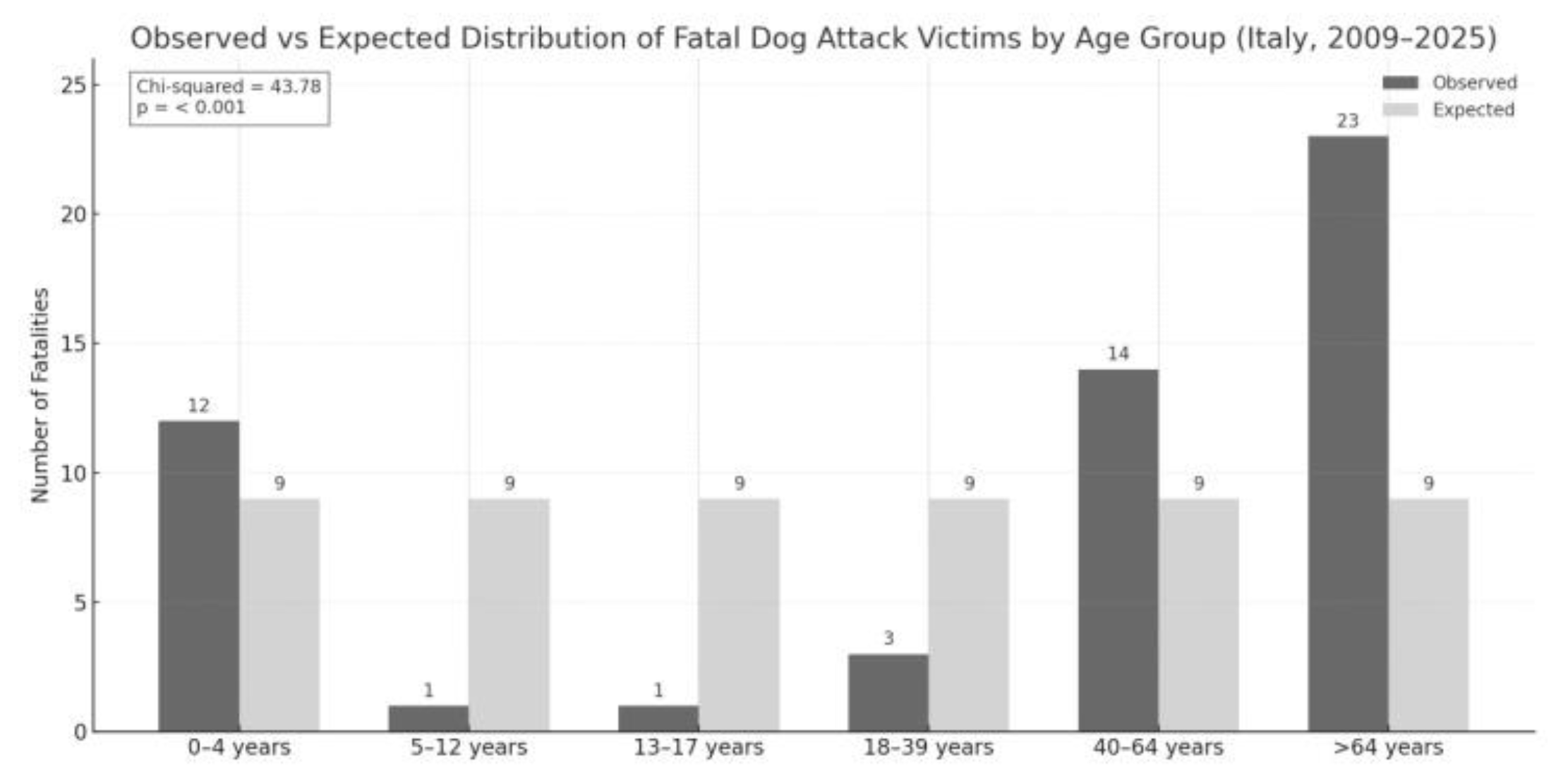

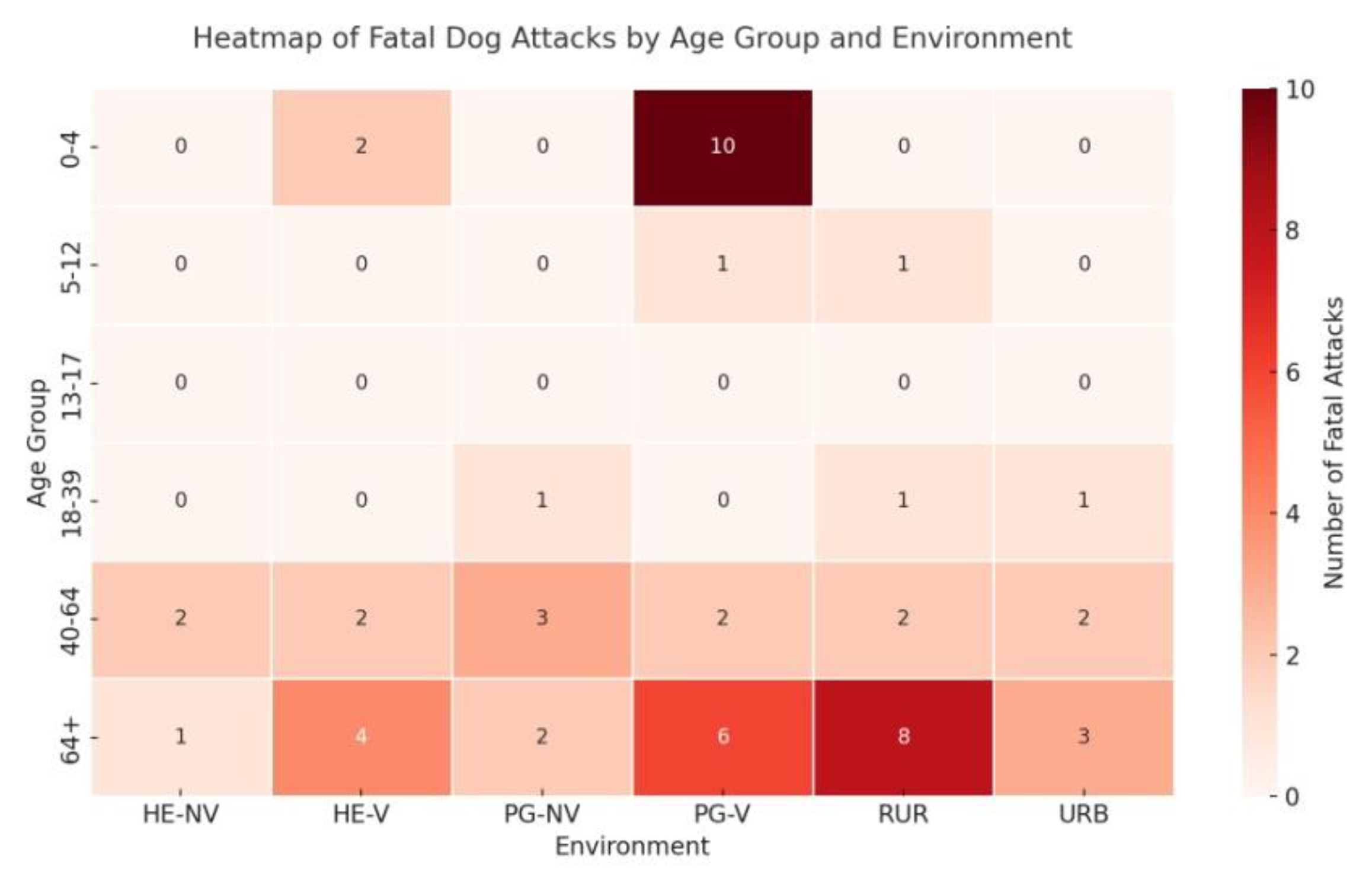

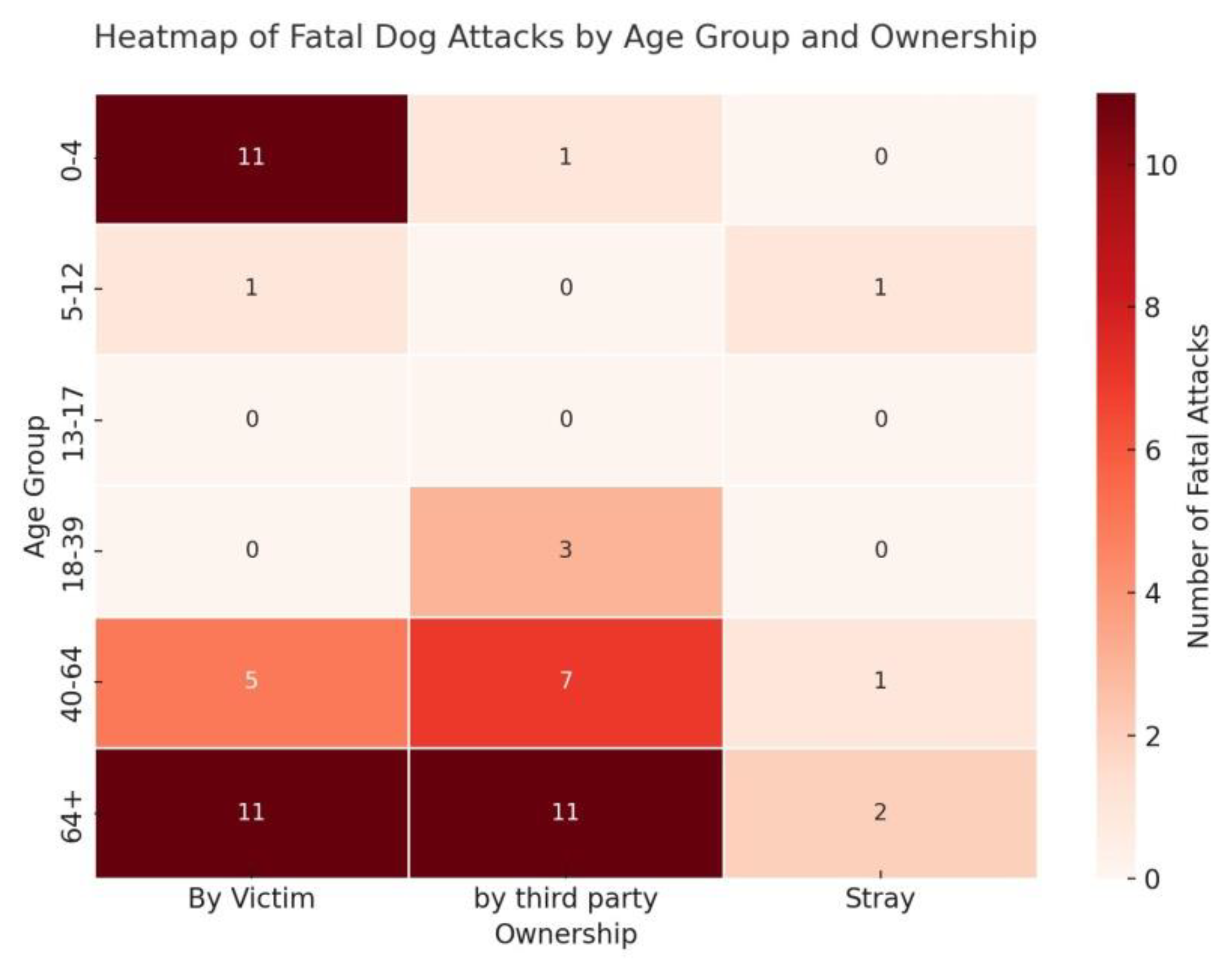

The analysis of victim demographics confirms heightened vulnerability at both ends of the age spectrum. Children aged 0–4 years and elderly individuals (≥64 years) were the most frequently affected groups. The heatmap analysis offers valuable insights: among young children, 91.7% of fatalities involved dogs owned by the victim's household, and 10 of the 12 deaths occurred in the family’s private garden (PG-V) (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). These findings clearly indicate that the risk does not arise from mere cohabitation with potentially dangerous dogs, but rather from the absence or inadequacy of adult supervision in domestic settings. Leaving very young children unattended in environments shared with animals of high injurious potential constitutes a serious and often underestimated hazard. This issue also carries legal implications: under Italian criminal law, specifically the Italian Penal Code (Articles 570 and 571), failure to adequately supervise minors—especially when it results in injury or death—may constitute criminal negligence. In this context, the lack of supervision in the presence of potentially dangerous dogs entails not only parental responsibility but also legal liability.

Among the elderly, the pattern is more heterogeneous. Fatalities were distributed across multiple environments—including private homes (HE-V), gardens (PG-V, PG-NV), and rural settings and involved dogs owned both by the victim and by third parties, as well as strays. This complexity may reflect the reduced ability of older individuals to respond to aggression or escape once an attack is initiated, irrespective of the context.

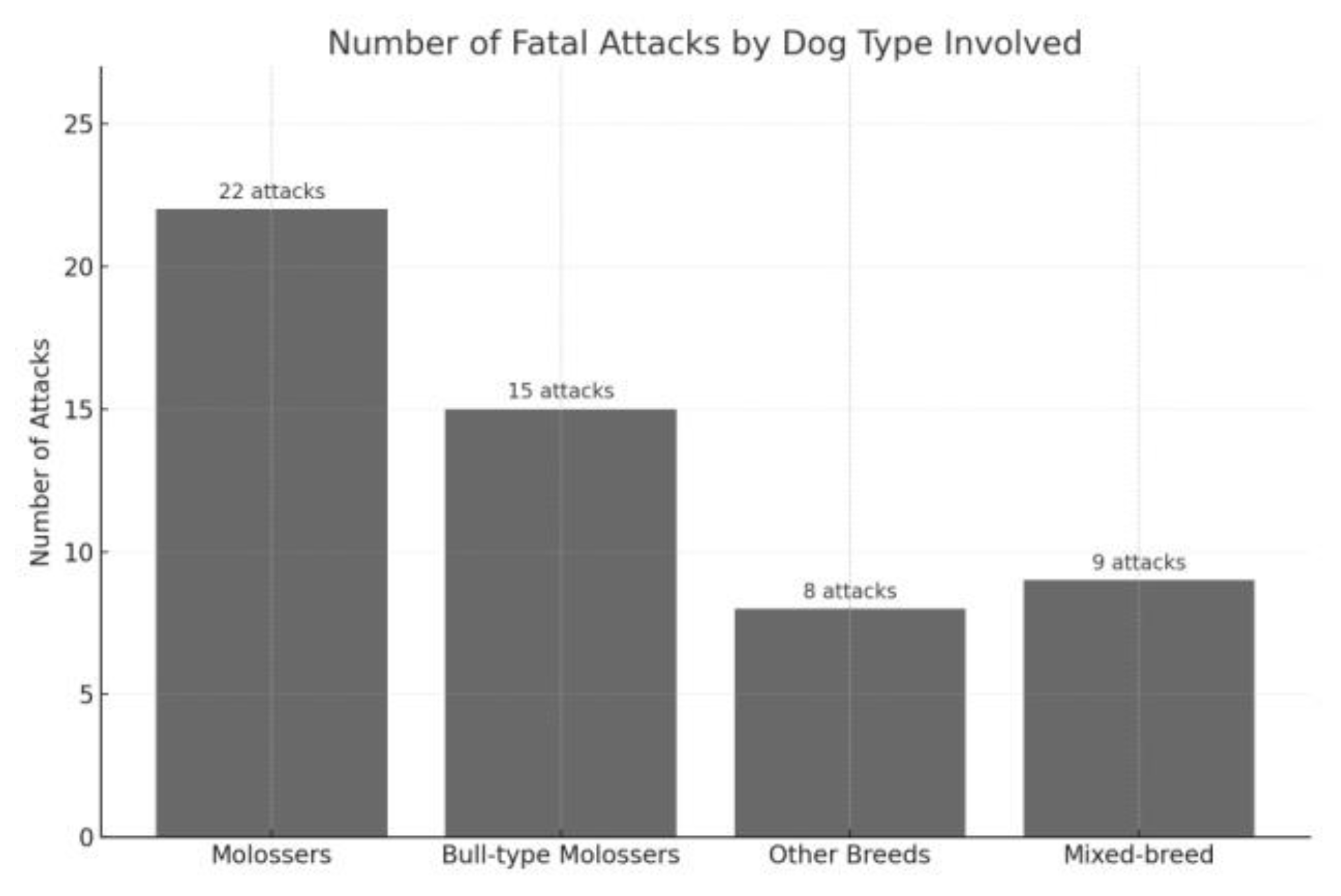

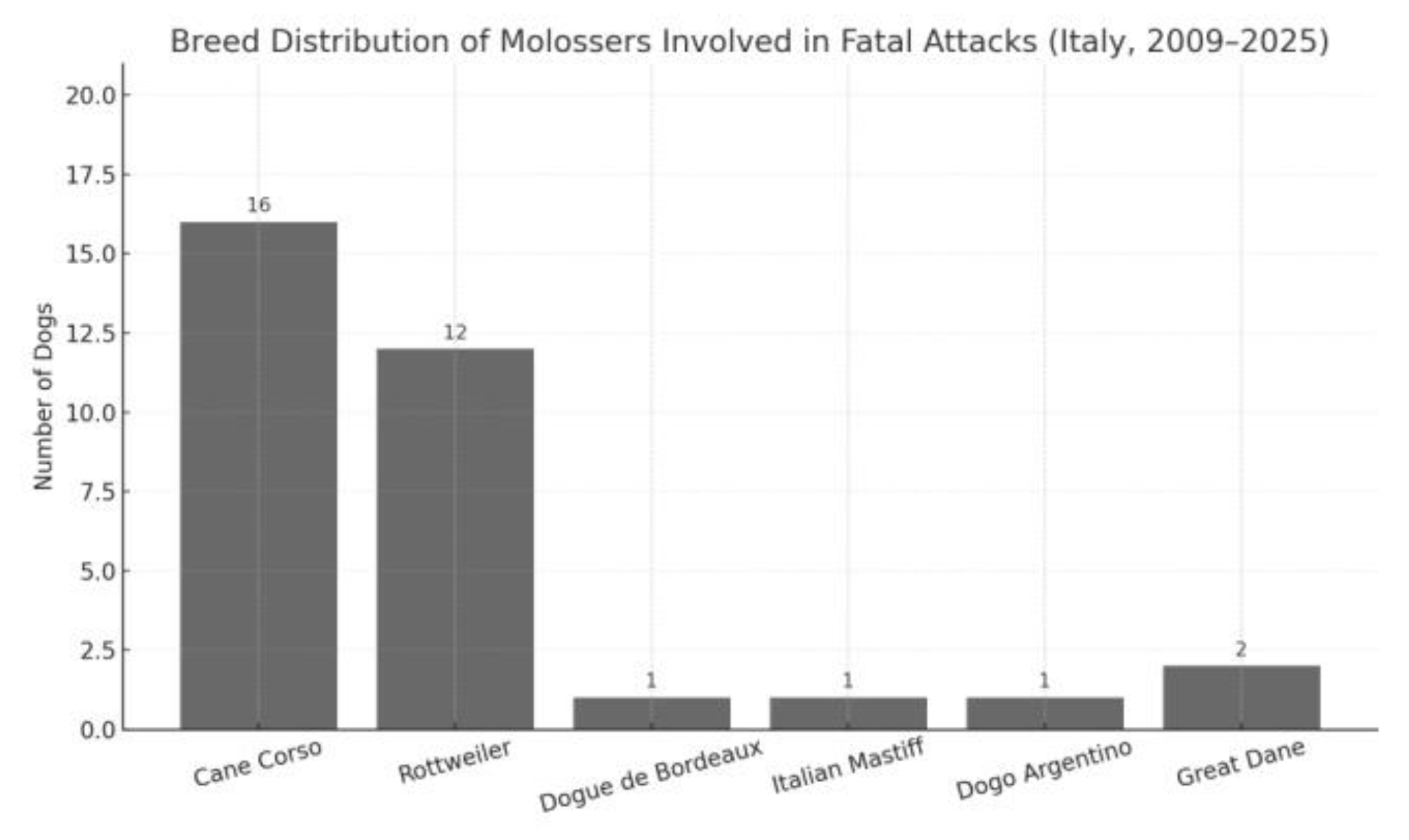

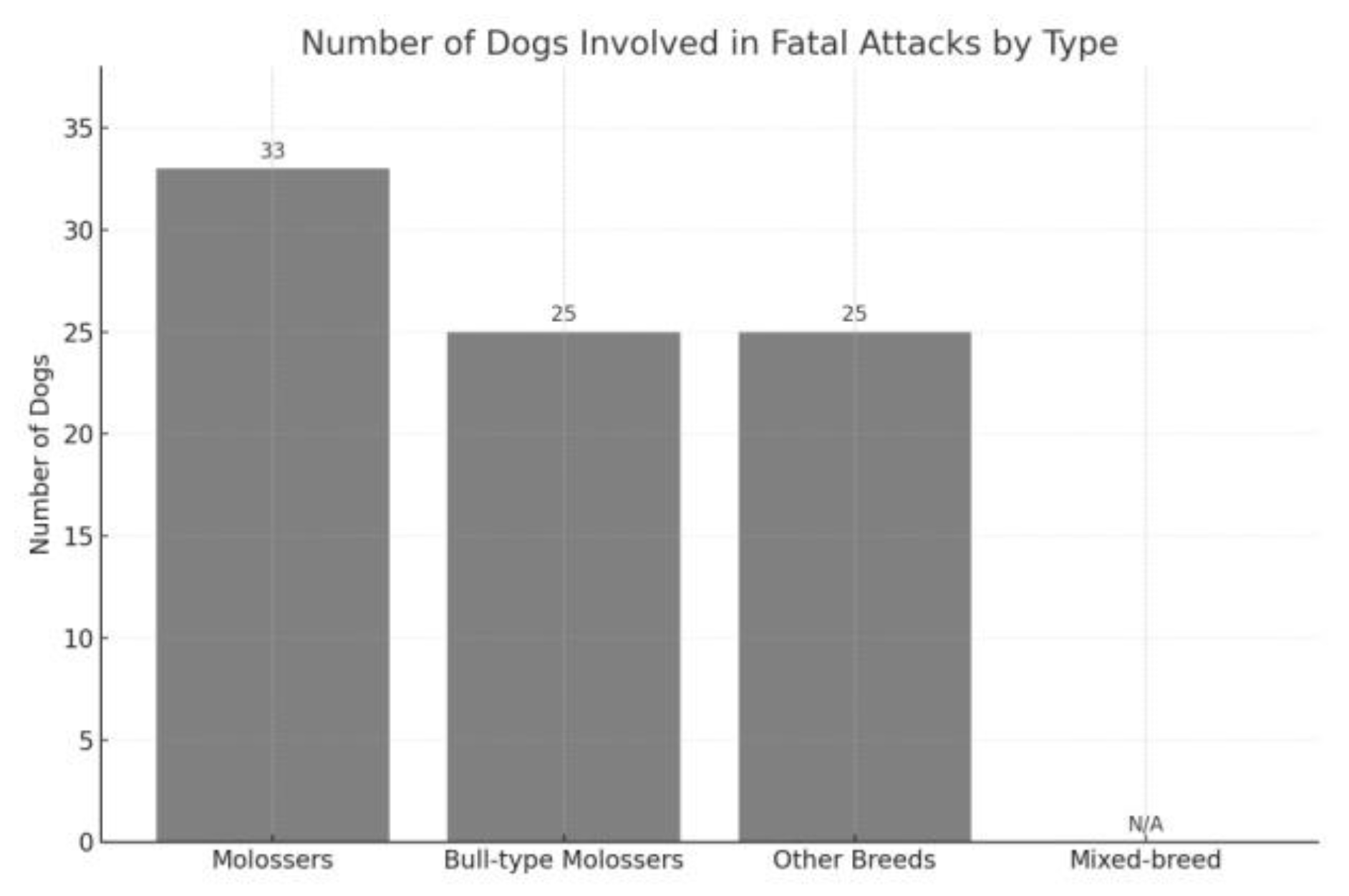

Our findings confirm a marked predominance of Molosser-type dogs in fatal attacks recorded in Italy between 2009 and 2025. In 22 of the 54 documented cases (41%), the attacking dogs belonged to this morphological group. This proportion closely mirrors that reported in the earlier study by Ciceroni and Gostinicchi (2009) [

3], where Molossers were involved in approximately 45% of fatal incidents recorded between 1984 and 2009.

However, a new and notable trend concerns bull-type Molossers. In the 1984–2009 dataset, no fatal attacks were attributed to this subgroup. In contrast, our current analysis identifies the first bull-type Molosser fatality in 2017, with a steady rise in subsequent years culminating in 15 fatal attacks involving these breeds. This increase suggests a growing prevalence of bull-type Molossers in the Italian canine population—possibly driven by market trends, cultural preferences, or an underestimation of the behavioral risks they may pose.

From an ethological standpoint, Molossers—particularly bull-type breeds—are characterized by behavioral traits that may increase the severity of aggressive incidents: strong bite retention, low thresholds for arousal, minimal warning signals prior to attack, and high resistance to pain or external deterrents [

15,

16]. These features do not imply inherent danger but do underscore the need for heightened awareness and responsible ownership.

In light of this evidence, renewed consideration should be given to implementing mandatory training programs for owners of breeds with high offensive potential. Such measures were previously embedded in Italian legislation until 2009 [

17]. As the ownership of dogs selectively bred for strength, endurance, and grip continues to expand, it is essential that handlers are fully informed of the associated responsibilities and risks.

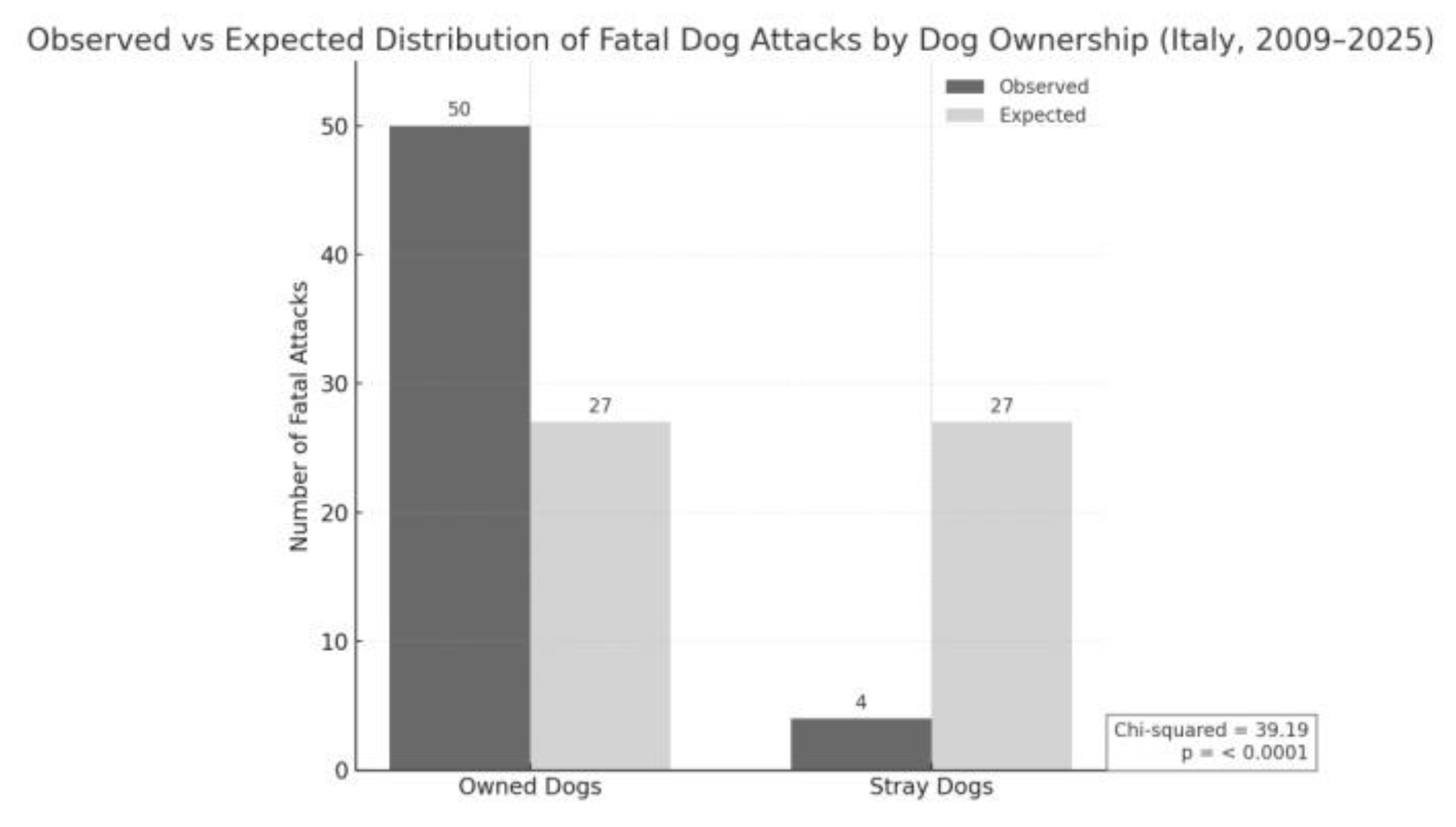

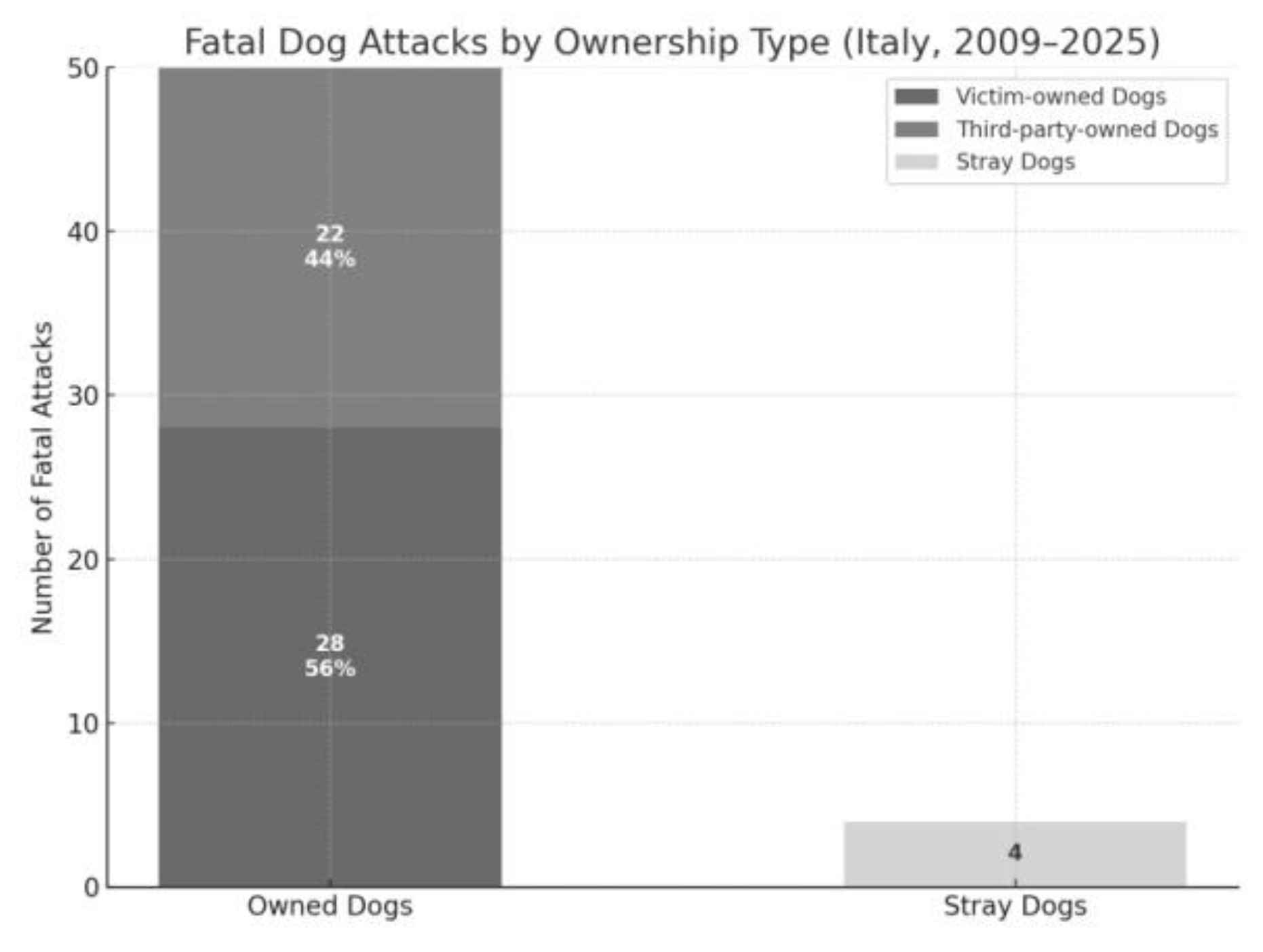

Against this backdrop of individual responsibility, the observed dynamics should be interpreted within a broader perspective that includes national exposure patterns and comparative international evidence. The analysis of Italian cases shows that over 92% of fatal attacks involved owned dogs, more than half belonging to the victim, underscoring the limitations of a prevention model based solely on individual owner responsibility. Only 7.4% of incidents involved stray dogs, confirming the effectiveness of the national stray control law (Framework Law 281/1991) [

18]. This finding suggests that the current challenge lies not in the management of stray dogs but in preventing aggressive behavior among owned animals and establishing effective behavioral monitoring mechanisms. Notably, in several documented cases, the attacking dogs had a known history of previous aggression, yet no corrective or preventive measures were implemented (

S2 – Supplementary Materials). This observation further emphasizes the need for proactive behavioral monitoring and intervention protocols.

At the European level, an analysis of Eurostat data from 19 countries (1995–2016) revealed a consistent rise in dog-related fatalities, with the highest incidence among children and elderly individuals [

19]. This trend situates the Italian experience within a broader context where shared demographic, social, and environmental factors contribute to increasing risk.

Similarly, a multicenter Turkish study conducted between 2014 and 2023 found that more than one-third of animal-attack deaths were attributed to dogs, predominantly in rural settings and mainly involving male victims [

20]. These findings indicate that in regions characterized by semi-owned dog populations and limited preventive policies, the likelihood of fatal attacks is amplified.

In a global context, the United States represents a paradigmatic case for comparison. Between 2020 and 2023, an average of more than 55 fatal dog attacks were recorded annually, with pit bulls implicated in over 60% of multi-dog incidents and a victim profile similar to that observed in Italy [

12] Unlike the European setting, however, the U.S. benefits from a centralized, publicly accessible database that compiles detailed data on breed, ownership, environmental context, and prior aggression history, enabling systematic surveillance and evidence-based policymaking. The database includes over twenty behavioral, demographic, and contextual variables for each case, allowing refined epidemiological comparison and risk modeling.

In light of these considerations, Italy would greatly benefit from establishing a national registry for monitoring dogs with behavioral risk, modeled on internationally validated systems. Such an instrument would harmonize data collection, facilitate early identification of high-risk subjects, and promote collaboration among veterinary medicine, forensic science, and public health authorities. Within this framework, the role of veterinarians remains pivotal, as emphasized by the World Veterinary Association [

21], which advocates a multidimensional approach based on clinical observation, responsible management, and environmental awareness.

Strengths and Limitations

This study represents the most comprehensive and methodologically rigorous epidemiological analysis of fatal dog attacks in Italy to date. By extending the observation window to 17 years and systematically collecting data from multiple verified journalistic sources, it fills a critical gap in national public health surveillance. The structured database enabled both descriptive and inferential statistical analysis, including multivariate modeling and interaction effects, which enhanced the depth and reliability of the findings.

The study also benefits from a multidisciplinary approach, integrating forensic, ethological, and legal perspectives. Comparative analysis with U.S. data further contextualizes the Italian experience and underscores the relevance of centralized behavioral risk monitoring systems. The identification of recurring victim profiles, breed involvement, and environmental contexts provides actionable insights for policymakers, veterinarians, and public health authorities.

Despite its strengths, the study is subject to several limitations. First, the reliance on journalistic sources (while necessary due to the absence of a national registry) may introduce reporting bias, incomplete coverage, or inaccuracies in breed identification and incident details. Although cross-verification and exclusion criteria were applied, the lack of access to forensic or veterinary records limits the ability to validate cases through institutional data.

Second, key variables such as the age, sex, and behavioral history of the attacking dogs were often unavailable, precluding more granular analysis. The retrospective design also restricts direct observation of environmental or behavioral triggers, relying instead on secondary descriptions that may lack nuance.

Third, while statistical modeling was employed to explore associations and predictors, the absence of standardized national data constrained the use of more advanced techniques such as survival analysis or spatial epidemiology. Finally, the study does not account for near fatal or non-lethal attacks, which may offer additional insights into risk dynamics and prevention strategies.

These limitations reinforce the urgent need for a centralized, publicly accessible national database—similar to the U.S. model—that systematically tracks fatal and non-fatal dog attacks, behavioral risk indicators, and intervention outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the most comprehensive epidemiological profile of fatal dog attacks in Italy to date, spanning a 17-year period and revealing persistent patterns of vulnerability, breed involvement, and environmental risk. Despite regulatory shifts toward owner accountability and behavioral monitoring, the number of fatalities has increased compared to the previous era of breed-specific legislation. The data underscore that fatal attacks are not random events but follow recurring dynamics, most notably involving molosser and bull-type breeds, owned dogs, and vulnerable victims such as preschool-aged children and the elderly.

The predominance of incidents in private settings, particularly within the victim’s own household, highlights the limitations of current prevention strategies and the urgent need for structural reform. Comparative analysis with the United States demonstrates the value of centralized, publicly accessible databases in tracking behavioral risk factors and informing policy. Italy’s reliance on fragmented reporting and the absence of a national registry severely constrain its ability to monitor trends, intervene early, and prevent future fatalities.

To address these gaps, we advocate for the creation of a national behavioral risk registry for dogs, integrated with veterinary, forensic, and public health systems. Such a registry should include mandatory reporting of aggressive incidents, standardized behavioral assessments, and enforceable intervention protocols. Only through coordinated, data-driven strategies can Italy move beyond reactive measures and toward a proactive model of canine aggression prevention—one that protects both human lives and animal welfare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.I. and F.S.; methodology, F.I. and F.S.; software, F.I. and F.S.; validation, F.I. and F.S.; formal analysis, F.I. and F.S.; investigation, F.I., F.S., S.P., M.F. and M.B.; resources, F.I., F.S., S.P., M.F., A.R., A.C. and M.B.; data curation, F.I., F.S., S.P., M.F., A.R., A.C. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.I. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.I. and F.S.; visualization, F.I. and F.S.; supervision, A.P., M.S. and C.P.; project administration, F.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

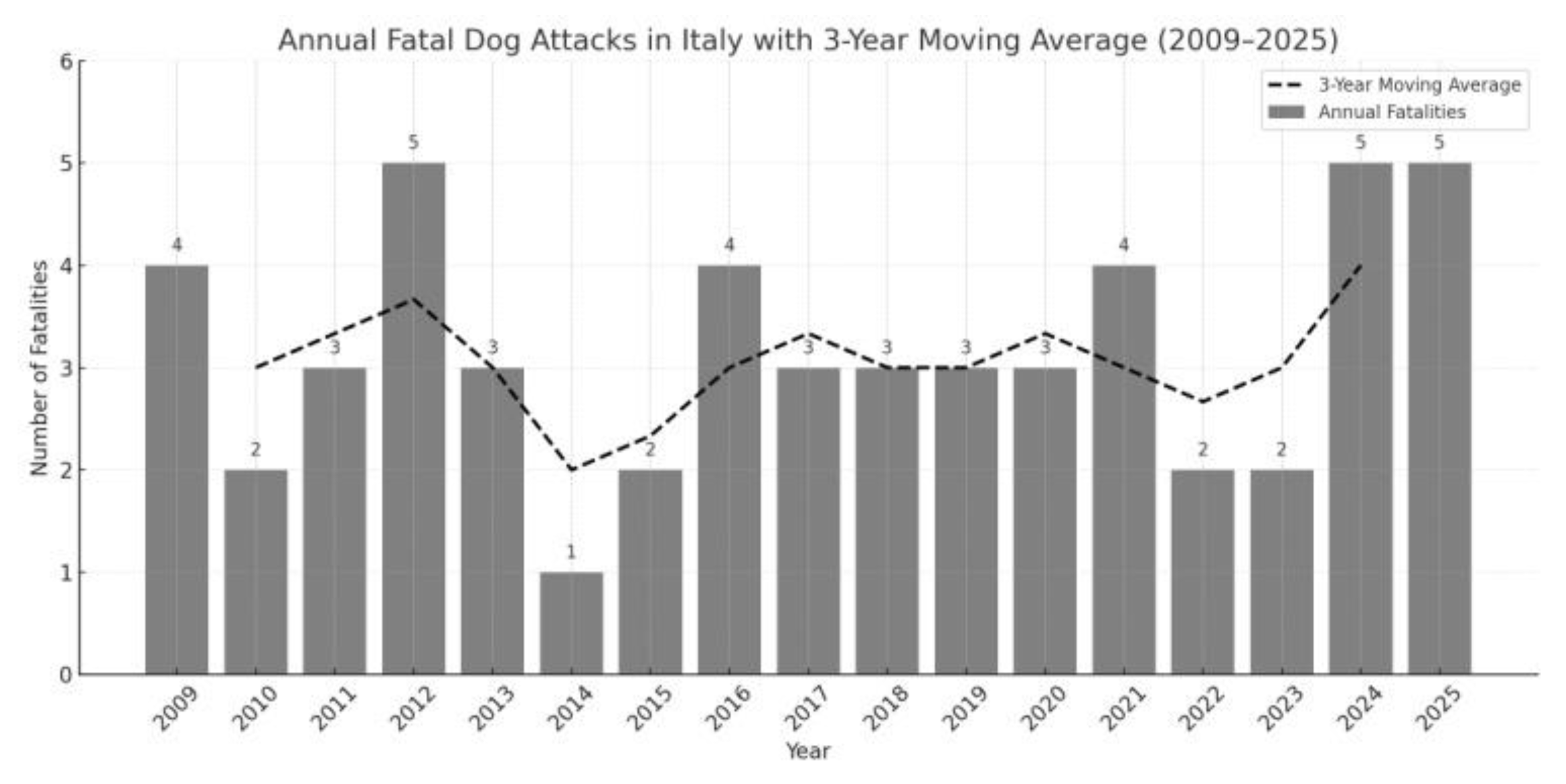

Figure 1.

Annual number of human fatalities resulting from fatal dog attacks in Italy from 2009 to 2025 (n = 54). Although a few peaks are observed (2012, 2024, 2025), the overall trend remains relatively stable throughout the study period.

Figure 1.

Annual number of human fatalities resulting from fatal dog attacks in Italy from 2009 to 2025 (n = 54). Although a few peaks are observed (2012, 2024, 2025), the overall trend remains relatively stable throughout the study period.

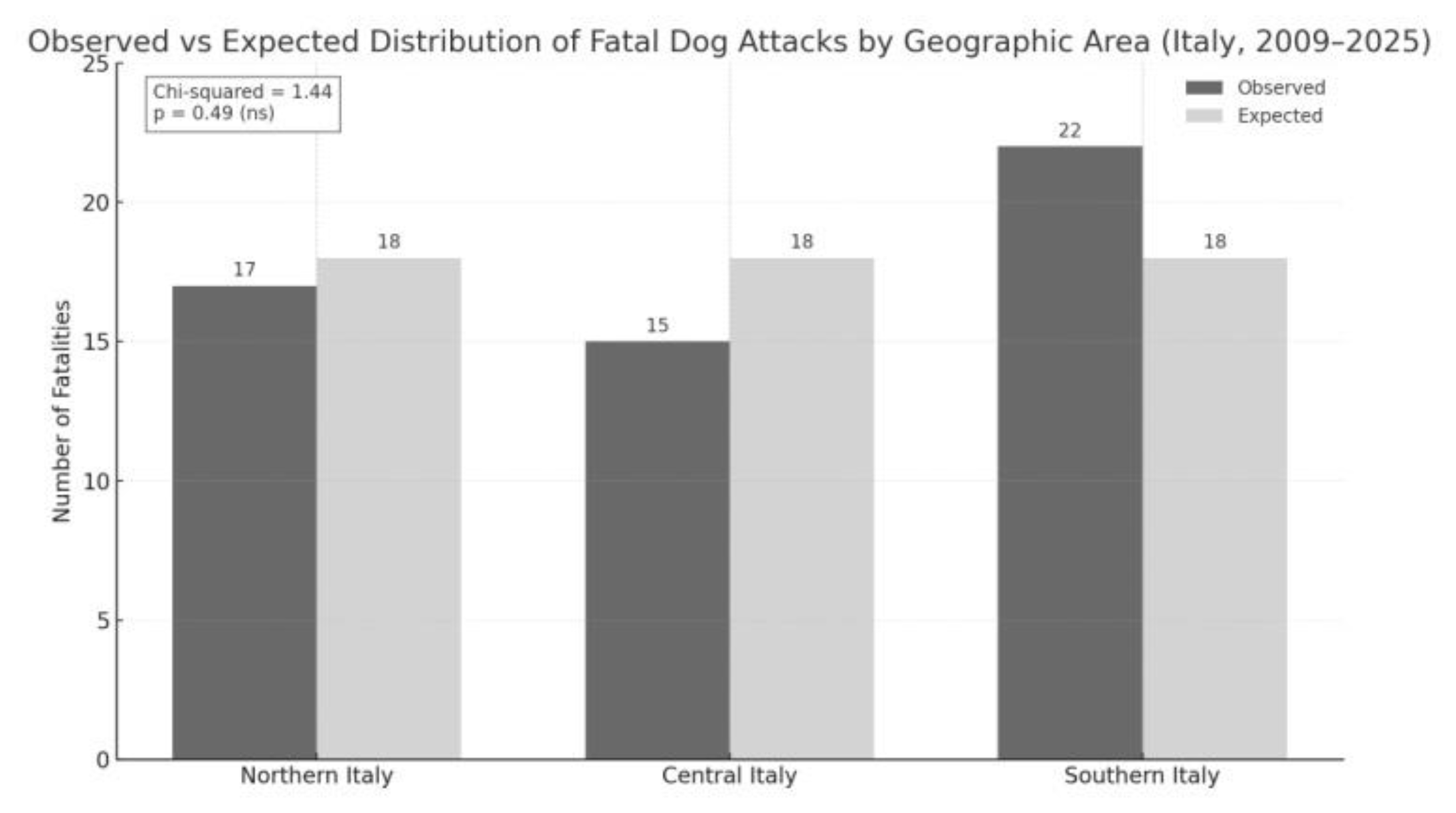

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of human fatalities resulting from fatal dog attacks in Italy between 2009 and 2025. Bars show observed and expected counts for each macro-region. The chi-squared test (χ² = 1.44; p = 0.49) revealed no statistically significant difference.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of human fatalities resulting from fatal dog attacks in Italy between 2009 and 2025. Bars show observed and expected counts for each macro-region. The chi-squared test (χ² = 1.44; p = 0.49) revealed no statistically significant difference.

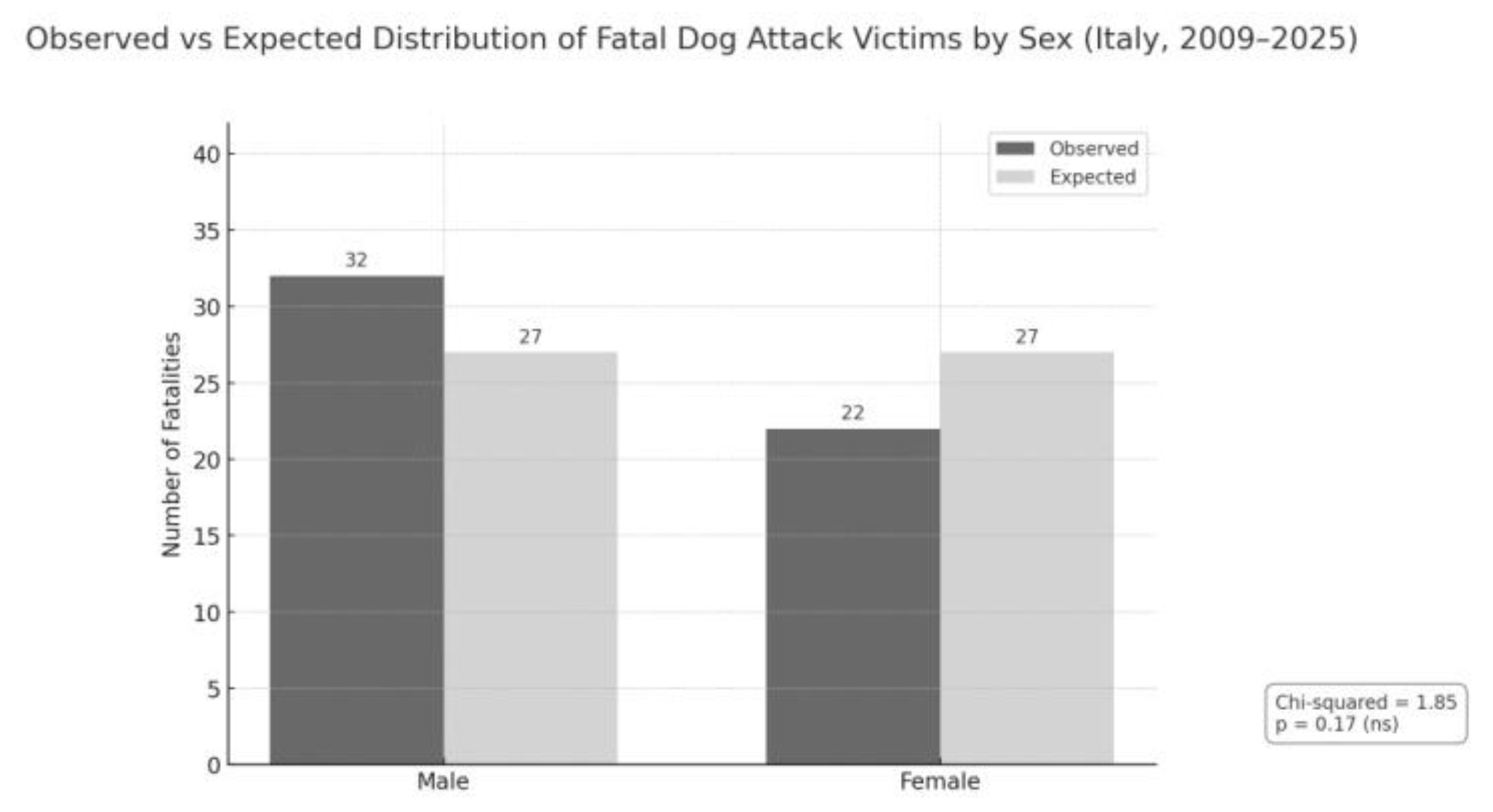

Figure 3.

Observed versus expected number of fatalities from dog attacks by sex in Italy (2009–2025). The slight predominance of male victims was not statistically significant, as indicated by the chi-squared test (χ² = 1.85; p = 0.17).

Figure 3.

Observed versus expected number of fatalities from dog attacks by sex in Italy (2009–2025). The slight predominance of male victims was not statistically significant, as indicated by the chi-squared test (χ² = 1.85; p = 0.17).

Figure 4.

Age-based distribution of human fatalities caused by dog attacks in Italy between 2009 and 2025. The analysis shows that both elderly individuals and young children experienced disproportionately high fatality counts compared to other age groups, as supported by a significant chi-squared result (χ² = 43.78; p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Age-based distribution of human fatalities caused by dog attacks in Italy between 2009 and 2025. The analysis shows that both elderly individuals and young children experienced disproportionately high fatality counts compared to other age groups, as supported by a significant chi-squared result (χ² = 43.78; p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Bar chart showing the frequency of fatal dog attacks in Italy by general dog type. Molossers were involved in the highest proportion of incidents (41%), followed by bull-type molossers (28%), mixed-breed dogs (17%), and other purebred dogs (15%).

Figure 5.

Bar chart showing the frequency of fatal dog attacks in Italy by general dog type. Molossers were involved in the highest proportion of incidents (41%), followed by bull-type molossers (28%), mixed-breed dogs (17%), and other purebred dogs (15%).

Figure 6.

Detailed breakdown of molosser breeds involved in fatal dog attacks. Cane Corso and Rottweiler were the most represented.

Figure 6.

Detailed breakdown of molosser breeds involved in fatal dog attacks. Cane Corso and Rottweiler were the most represented.

Figure 7.

Stacked bar chart comparing the total number of individual dogs implicated in fatal attacks, grouped by general dog type.

Figure 7.

Stacked bar chart comparing the total number of individual dogs implicated in fatal attacks, grouped by general dog type.

Figure 8.

The vast majority of fatal attacks between 2009 and 2025 were committed by owned dogs (n = 50), while only a small fraction involved stray dogs (n = 4).

Figure 8.

The vast majority of fatal attacks between 2009 and 2025 were committed by owned dogs (n = 50), while only a small fraction involved stray dogs (n = 4).

Figure 9.

Among the 50 fatal attacks involving owned dogs, 56% were perpetrated by dogs owned by the victim, and 44% by dogs belonging to third parties.

Figure 9.

Among the 50 fatal attacks involving owned dogs, 56% were perpetrated by dogs owned by the victim, and 44% by dogs belonging to third parties.

Figure 10.

Distribution of fatal dog attacks across private and public settings, highlighting a higher concentration of events within privately controlled environments. Legend: HE-NV = Non-victim home environment; PG-V = Victim’s private garden; PG-NV = Non-victim private garden; RUR = Rural environment; URB = Urban environment.

Figure 10.

Distribution of fatal dog attacks across private and public settings, highlighting a higher concentration of events within privately controlled environments. Legend: HE-NV = Non-victim home environment; PG-V = Victim’s private garden; PG-NV = Non-victim private garden; RUR = Rural environment; URB = Urban environment.

Figure 11.

Heatmap of fatal dog attacks by victim age group and environment. Children (0–4 years) were mainly attacked in their own gardens, while elderly victims (≥65) were most often involved in rural settings. Adults (40–64) showed a more varied distribution across environments.

Figure 11.

Heatmap of fatal dog attacks by victim age group and environment. Children (0–4 years) were mainly attacked in their own gardens, while elderly victims (≥65) were most often involved in rural settings. Adults (40–64) showed a more varied distribution across environments.

Figure 12.

Heatmap of fatal dog attacks in Italy (2009–2025) by victim age group and dog ownership. Children (0–4 years) were attacked almost exclusively by dogs from their own household, adults (18–39) by dogs owned by third parties, and the elderly (≥65) mainly by dogs of third parties. Stray dogs were rarely involved.

Figure 12.

Heatmap of fatal dog attacks in Italy (2009–2025) by victim age group and dog ownership. Children (0–4 years) were attacked almost exclusively by dogs from their own household, adults (18–39) by dogs owned by third parties, and the elderly (≥65) mainly by dogs of third parties. Stray dogs were rarely involved.