Submitted:

29 September 2023

Posted:

01 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

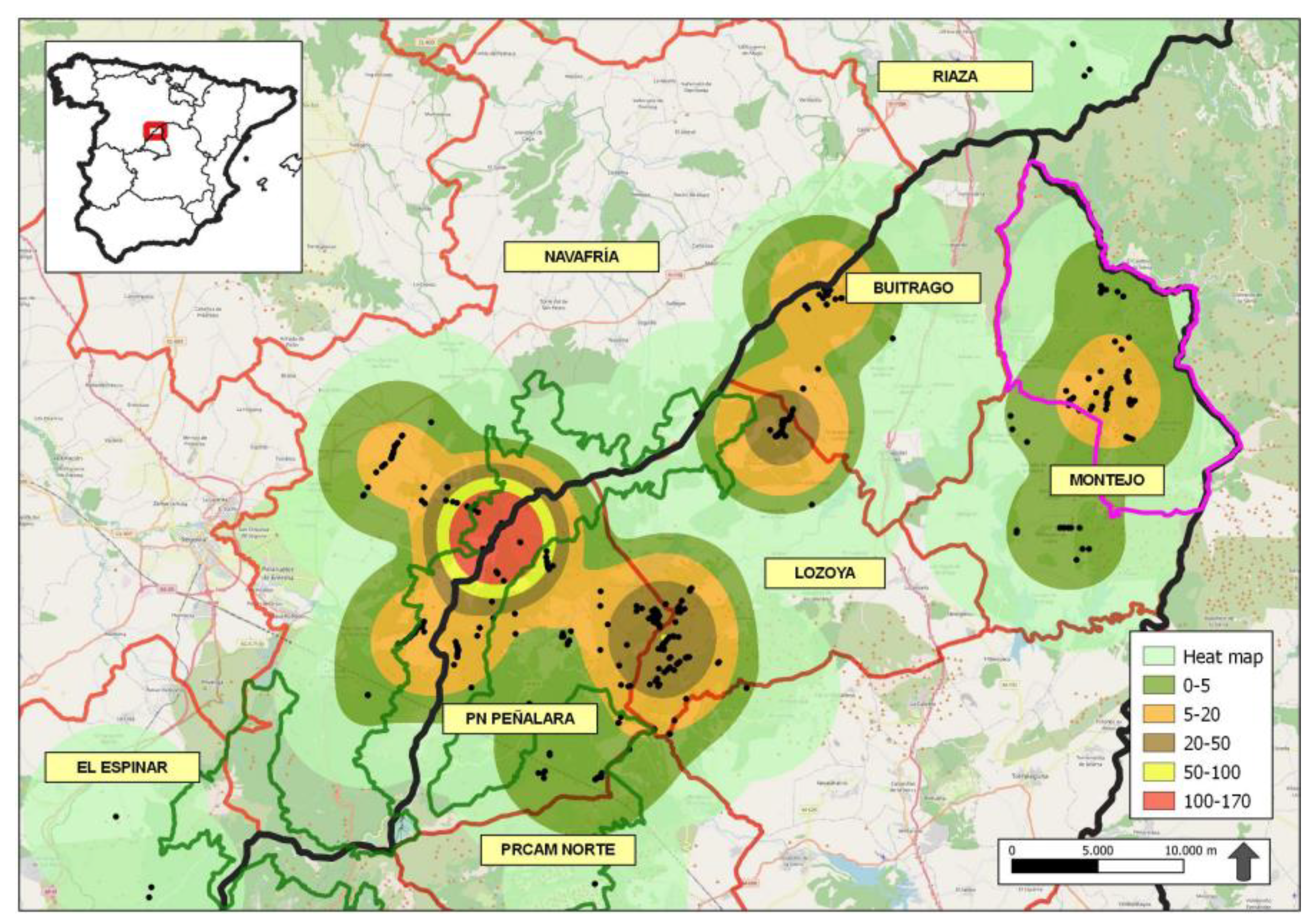

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Protection Measures for the Iberian Wolf and Its Conservation Conflicts

2.3. Collection of Faecal Samples

2.4. Identification of Wolf Prey Species

2.5. Mapping Using Kernel Densities

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Remarks

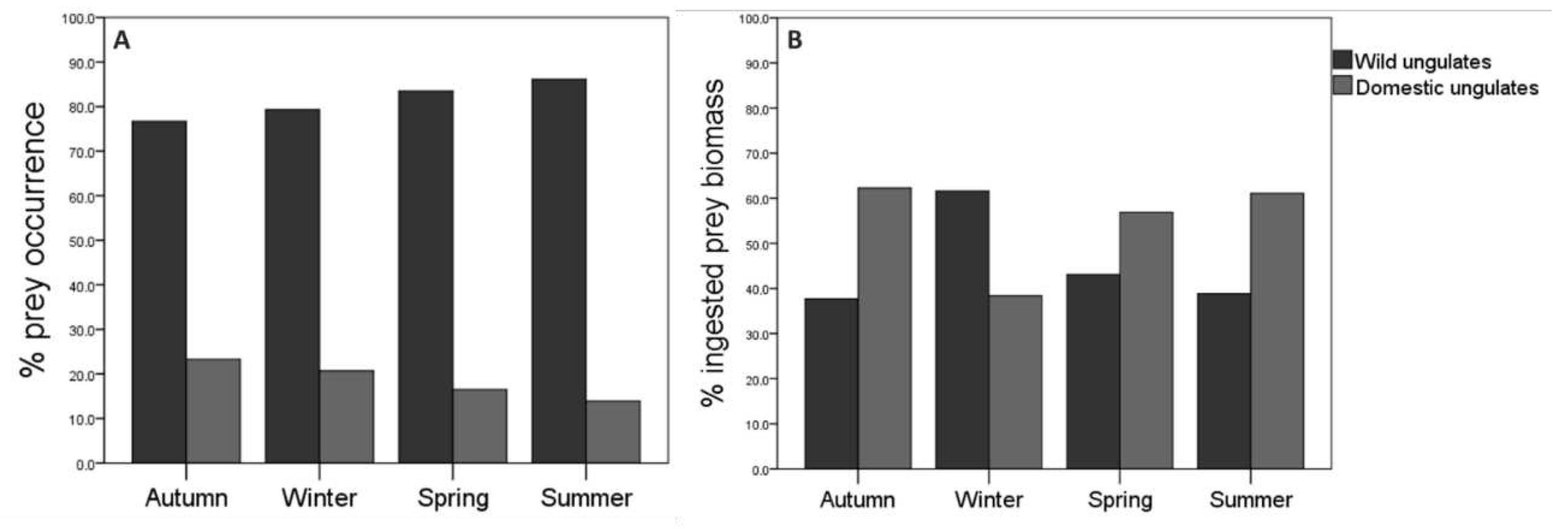

3.2. Seasonal Trends

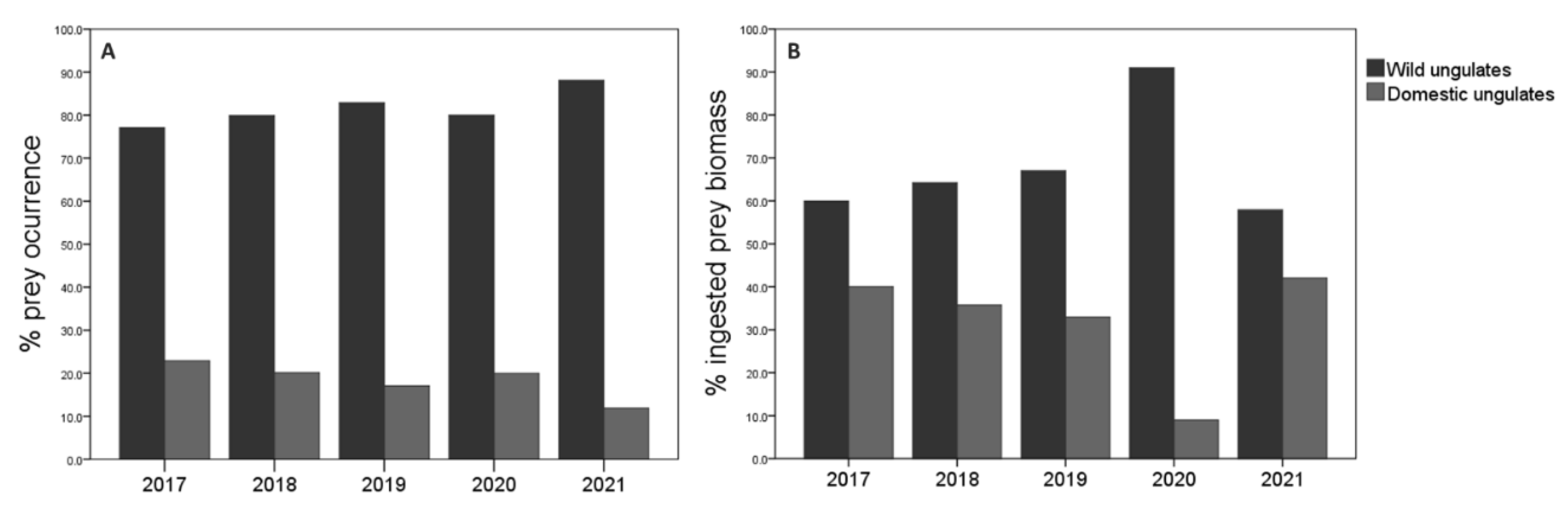

3.3. Annual Trends

3.4. Forest Regions Trends

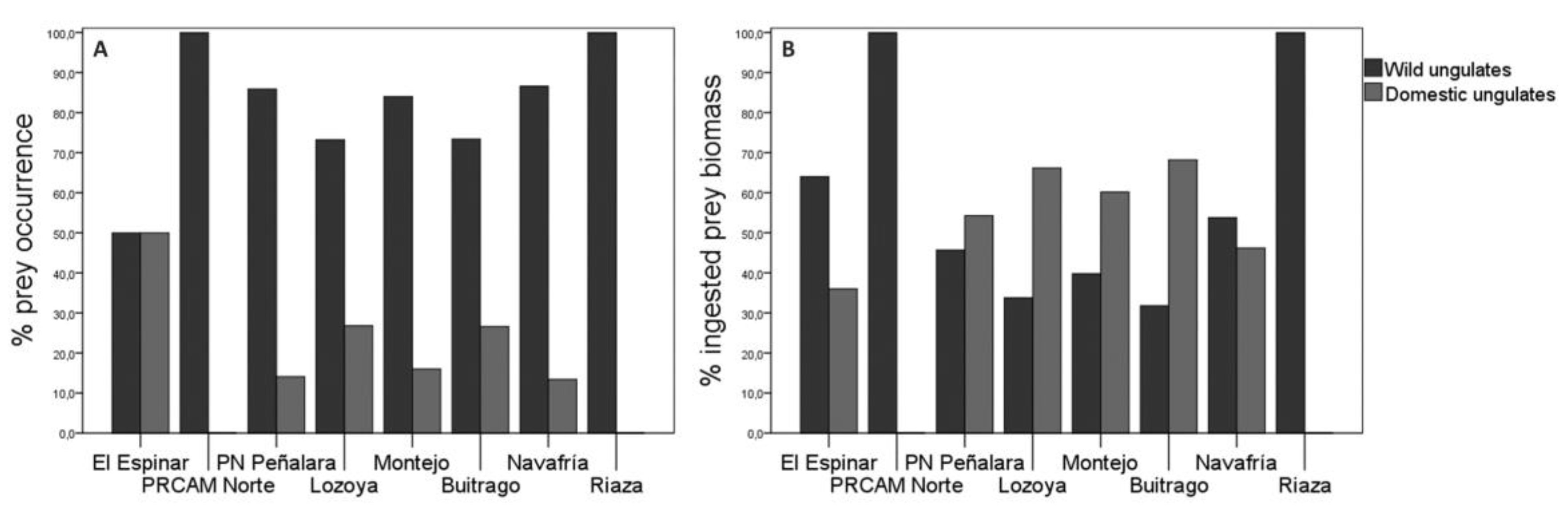

4. Discussion

- The diet of wolves in the Sierra de Guadarrama, Sierra del Rincón and surroundings primarily consists of wild ungulates, like other regions in Europe [41,77,84,85]. However, there were differences in wolf diet compared to areas south of the Duero River in the Iberian Peninsula [11]. Our study area is characterized by a multi-prey ecosystem and well-distributed wild ungulates, such as roe deer and wild boar. This could explain why these species were the main prey, while consumption of domestic livestock, particularly free-roaming cattle, was minimal. Additionally, the larger size of adult cattle makes them a challenging target for wolves, with attacks primarily targeting calves.

- Wild boar was the predominant prey, in terms of the most frequently encountered species in wolf scat samples, followed by roe deer, which is consistent with aligns with Mori et al. [86] in Italy. Wild boar populations in the Iberian Peninsula increased throughout the region since the 21st century [87,88,89], even at high elevations [90], while roe deer populations are strongly associated with forested areas [44,91]. This difference in the availability distribution explains why the most consumed prey was wild boar, although wolves heavily rely on roe deer as well. Ivlev’s index supports this conclusion, indicating positive selection for roe deer and wild boar compared to other prey species. When considering the percentage of ingested biomass, cattle were the most consumed species, but this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the difference in body size between cattle and other prey species (e.g., cattle outweigh wild boar by a factor of 10).

- Regarding seasonal patterns, the consumption of wild ungulates based on the percentage of appearance of prey was higher in spring and summer (reproductive and breeding season), decreasing its consumption in autumn and winter. In contrast, the consumption of domestic ungulates was higher in autumn and winter. Pups abound in spring and summer and are an easy prey for wolves, given their inexperience [23,92]. The scarcity of this prey species during the colder seasons can compromise cattle and they may be perceived more attractive to wolves. Specifically, roe deer was the most consumed prey in all seasons, except spring when wild boar became the predominant prey, likely due to the high reproductive rate and larger litters (ẋ=3.5 ind.; [43]) of wild boar compared to roe deer (ẋ=1.46 ind.; [93]). When considering ingested biomass, cattle consistently contribute the highest percentage in all seasons due to their larger body size. FNB findings suggest that wolves exhibit a specialized diet during spring and summer, while showing a more general feeding pattern in autumn and winter. During the reproductive seasons (spring and summer), wolves have a larger pool of prey to choose from, due to the increased population of ungulates resulting from birthing season. This allows them to selectively target specific prey and specialize their diet according to resources availability. Conversely, in winter, when food availability is limited, the wolf’s diet becomes more generalized, consuming both domestic species and wild ones. This suggests that the wolf in the study area is a facultative specialist species, adapting its feeding behavior depending on the seasons.

- In terms of annual patterns, the consumption of wild ungulates is higher than domestic ungulates. Wolf’s diet was mainly based on roe deer from 2017 to 2019, while wild boar prevailed in recent years, possibly due to a decrease in roe deer populations (F. Horcajada, unpublished data) since the establishment of wolves in the area. The presence of red deer in wolf scats in 2019, despite not being generally present in the study area (although it is present in the eastern and southern surroundings), could be attributed to the dispersal behavior of wolves [94,95] or bait placement by hunters [96] or intended for study by researchers [36]. Consumption on mountain goats was sporadic, except for a slight increase in 2019. Mountain goat frequent rough areas that are difficult to access and/or guarantee a successful attack from wolves [97]. Wolves prefer steep slopes and open habitats where wild ungulates are more easily detectable and accessible [98], which may explain their lower consumption of mountain goats. The consumption of domestic horse in 2019 was a sporadic event, likely consumed as carrion. Based on FNB, and considering the % occurrence of prey in scats, the wolf followed a specialist diet every year feeding on wild ungulates instead of domestic ones. However, based on the biomass ingested, the wolf diet could be considered generalist, except in 2021. This could be due to the different size of the preys, as previously discussed.

- Regarding the forest region pattern, wolves fed mainly on wild ungulates, especially roe deer and wild boar, in all forest regions. Among species of domestic ungulates, cattle were the most consumed prey. In most of the forest regions, the presence of cattle is greater than that of sheep and goats, except Navafría where goats and sheep are predominant (INE 2020). Although cattle are more numerous in most forest regions, the prey selection index was higher for sheep and goats. However, in the case of Navafría, where the presence of cattle is lower, wolves positively selected cattle and avoided sheep and goats.

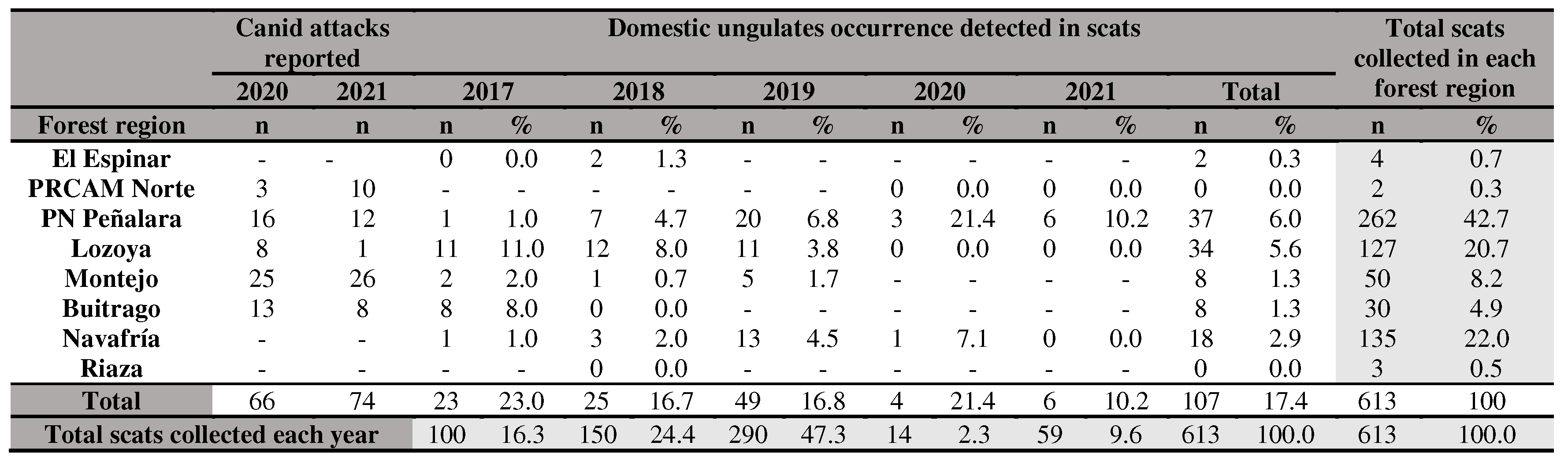

- Finally, an important concern in the study area is the inconsistency between official data on canid attacks on livestock provided by the Comunidad de Madrid and the findings regarding the wolf’s diet in different forest regions. For instance, the consumption of wild ungulates in PN Peñalara was significantly higher (2020: 78.6%, n=6; 2021: 88.2%, n=45) compared to domestic ungulates (2020: 21.4%, n=3; 2021: 10.2%, n=6 in PN Peñalara; Table 2). In Montejo, where the highest number of attacks was recorded, it paradoxically had one of the lowest consumption rates of domestic ungulates from 2017 to 2019. Despite the lack of diet data for Montejo in 2020-2021, which coincides with the peak number of attacks, the pattern of low domestic ungulates consumption in previous years suggests that the attacks may be primarily caused by other canids such as dogs rather than wolves. The higher number of attacks registered in 2020 and 2021 compared to the detection of domestic ungulate remains in wolf scats similar prey diversity indices in other regions like Buitrago (H’=1.27) and PN Peñalara (H’=1.22), further supports this hypothesis. We were unable to draw conclusions about the El Espinar, PRCAM Norte and Riaza forest regions due to low sample size.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Equation of Floyd et al. (1978), revised and adjusted by Weaver (1993)

Shannon Diversity Index Calculation

Niche Breadth (Levin’s Index) Calculation

Ivelev’s Electivity Index Calculation

Appendix B

Seasonal variation of wolf diet (n=637; pooled years)

| Prey occurrence | Ingested biomass | |||||

| Prey | Season | n | % | Kg | % | |

| Wild ungulates | Roe deer | Autumn | 83 | 43.9 | 141.4 | 13.2 |

| Winter | 49 | 44.1 | 83.5 | 20.1 | ||

| Spring | 76 | 38.0 | 129.4 | 10.7 | ||

| Summer | 73 | 53.3 | 124.3 | 15.5 | ||

| Red deer | Autumn | 1 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 0.5 | |

| Winter | 0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 1.2 | ||

| Spring | 1 | 0.5 | 5.1 | 0.4 | ||

| Summer | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Wild boar | Autumn | 54 | 28.5 | 233.2 | 21.8 | |

| Winter | 38 | 34.2 | 164.1 | 39.5 | ||

| Spring | 86 | 43.0 | 371.4 | 30.8 | ||

| Summer | 38 | 27.7 | 164.1 | 20.5 | ||

| Mountain goat | Autumn | 7 | 3.7 | 23.2 | 2.2 | |

| Winter | 1 | 0.9 | 3.3 | 0.8 | ||

| Spring | 4 | 2.0 | 13.3 | 1.1 | ||

| Summer | 7 | 5.1 | 23.2 | 2.9 | ||

| Total | Autumn | 145 | 76.7 | 402.8 | 37.7 | |

| Winter | 88 | 79.3 | 255.9 | 61.6 | ||

| Spring | 167 | 83.5 | 519.2 | 43.1 | ||

| Summer | 118 | 86.1 | 311.6 | 38.9 | ||

| Domestic ungulates | Cattle | Autumn | 18 | 9.5 | 630.7 | 59.1 |

| Winter | 4 | 3.6 | 140.2 | 33.7 | ||

| Spring | 19 | 9.5 | 665.7 | 55.2 | ||

| Summer | 13 | 9.5 | 455.5 | 56.9 | ||

| Domestic goat | Autumn | 12 | 6.3 | 20.34 | 1.9 | |

| Winter | 3 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 1.2 | ||

| Spring | 8 | 4.0 | 13.6 | 1.1 | ||

| Summer | 5 | 3.6 | 8.5 | 1.1 | ||

| Sheep | Autumn | 8 | 4.2 | 14.3 | 1.3 | |

| Winter | 3 | 2.7 | 14.2 | 3.5 | ||

| Spring | 4 | 2.0 | 7.1 | 0.6 | ||

| Summer | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Horse | Autumn | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Winter | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Spring | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Summer | 1 | 0.7 | 24.8 | 3.1 | ||

| Unidentified Livestock |

Autumn | 6 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Winter | 13 | 11.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Spring | 2 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Summer | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Total | Autumn | 44 | 23.3 | 665.3 | 62.3 | |

| Winter | 23 | 20.7 | 159.5 | 38.4 | ||

| Spring | 33 | 16.5 | 686.4 | 56.9 | ||

| Summer | 19 | 13.9 | 488.8 | 61.1 | ||

| Season | Faecal samples collected (n) | % Wild ungulates occurrence | % Domestic ungulates occurrence |

Statistical results in each season (wild vs domestic) |

| Autumn | 189 | 76.7 | 23.3 | χ2= 53.97; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Winter | 111 | 79.3 | 20.7 | χ2= 8.06; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Spring | 200 | 83.5 | 16.5 | χ2= 89.78; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Summer | 137 | 86.1 | 13.9 | χ2= 71.54; df=1; p=0.001 |

|

Statistical results in all seasons (Wild species vs domestic species) |

χ2=16.81; df=9; p=0.037, n=518 | χ2= 43.59; df=12; p=0.001, n=119 | ||

Percentage of occurrence of wild and domestic ungulates according to seasons. Statistical results according to season comparing the consumption of domestic or wild ungulates, respectively.

| Occurrence (n) | Biomass (Kg) | |||||

| B’ | B’ | |||||

| Wild/Dom | Wild/Wild | Dom/Dom | Wild/Dom | Wild/Wild | Dom/Dom | |

| Autumn | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.57 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| Winter | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

| Spring | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| Summer | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| Number of preys | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

Yearly changes of Iberian wolf diet (n=637; pooled seasons)

| Prey occurrence | Ingested biomass | |||||

| Prey | Years | n | % | Kg | % | |

| Wild ungulates | Roe deer | 2017 | 53 | 48.7 | 90.3 | 20.0 |

| 2018 | 87 | 51.5 | 148.2 | 20.4 | ||

| 2019 | 119 | 41.5 | 202.7 | 10.8 | ||

| 2020 | 9 | 30.0 | 15.3 | 5.3 | ||

| 2021 | 13 | 31.0 | 22.1 | 16.5 | ||

| Red deer | 2017 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2018 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2019 | 2 | 0.7 | 10.1 | 0.6 | ||

| 2020 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2021 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Wild boar | 2017 | 31 | 28.4 | 133.9 | 29.6 | |

| 2018 | 47 | 27.8 | 203.0 | 27.9 | ||

| 2019 | 100 | 34.8 | 431.9 | 23.0 | ||

| 2020 | 14 | 46.7 | 60.5 | 20.9 | ||

| 2021 | 24 | 57.1 | 103.7 | 77.1 | ||

| Mountain goat | 2017 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2018 | 1 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 0.5 | ||

| 2019 | 17 | 5.9 | 56.4 | 3.0 | ||

| 2020 | 1 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 1.1 | ||

| 2021 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Total | 2017 | 84 | 77.1 | 224.2 | 49.6 | |

| 2018 | 135 | 79.9 | 354.5 | 48.8 | ||

| 2019 | 238 | 82.9 | 701.1 | 37.4 | ||

| 2020 | 24 | 80.0 | 79.1 | 27.3 | ||

| 2021 | 37 | 88.1 | 125.8 | 93.6 | ||

| Domestic ungulates | Cattle | 2017 | 6 | 5.5 | 210.2 | 46.5 |

| 2018 | 10 | 5.9 | 350.4 | 48.3 | ||

| 2019 | 32 | 11.2 | 1121.3 | 59.8 | ||

| 2020 | 6 | 20.0 | 210.2 | 72.7 | ||

| 2021 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Domestic goat | 2017 | 6 | 5.5 | 10.2 | 2.3 | |

| 2018 | 8 | 4.7 | 13.5 | 1.9 | ||

| 2019 | 11 | 3.8 | 18.7 | 0.9 | ||

| 2020 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2021 | 3 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 3.8 | ||

| Sheep | 2017 | 4 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 1.6 | |

| 2018 | 4 | 2.4 | 7.1 | 0.9 | ||

| 2019 | 5 | 1.7 | 8.9 | 0.5 | ||

| 2020 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2021 | 2 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 2.7 | ||

| Horse | 2017 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2018 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2019 | 1 | 0.3 | 24.8 | 1.6 | ||

| 2020 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2021 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Unidentified livestock | 2017 | 9 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| 2018 | 12 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2019 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2020 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| 2021 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Total | 2017 | 25 | 22.9 | 227.5 | 50.4 | |

| 2018 | 34 | 20.1 | 371.0 | 51.1 | ||

| 2019 | 49 | 17.1 | 1173.7 | 62.6 | ||

| 2020 | 6 | 20.0 | 210.2 | 72.7 | ||

| 2021 | 5 | 11.9 | 8.7 | 6.4 | ||

| Year | Faecal samples collected (n) | % Wild ungulates occurrence | % Domestic ungulates occurrence |

Statistical results in each year (wild vs domestic) |

| 2017 | 109 | 77.1 | 22.9 | χ2=31.94; df=1; p=0.001 |

| 2018 | 169 | 79.9 | 20.1 | χ2=60.36; df=1; p=0.001 |

| 2019 | 287 | 82.9 | 17.1 | χ2=124.46; df=1; p=0.001 |

| 2020 | 30 | 80.0 | 20.0 | χ2=10.80; df=1; p=0.001 |

| 2021 | 42 | 88.1 | 11.9 | χ2=24.38; df=1; p=0.001 |

|

Statistical results in all years (wild species vs domestic species) |

χ2=16.81; df=9; p=0.037, n=518 | χ2= 43.59; df=12; p=0.001, n=119 | ||

| Ocurrence (n) | Biomass (Kg) | |||||

| B’ | B’ | |||||

| Wild/Dom | Wild/Wild | Dom/Dom | Wild/Dom | Wild/Wild | Dom/Dom | |

| 2017 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

| 2018 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.00 |

| 2019 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.35 | 0.90 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| 2020 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.70 | 0.20 | 0.00 |

| 2021 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.30 |

| Number of preys | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

Comparative of composition of Iberian wolf diet between forest regions based on 637 scats. The ingested prey biomass (in kg) was calculated using body masses.

| Prey occurrence | Ingested biomass | |||||

| Prey | Forest region | n | % | Kg | % | |

| Wild ungulates | Roe deer | El Espinar | 1 | 25.0 | 1.7 | 18.1 |

| PRCAM Norte | 1 | 50.0 | 1.7 | 28.3 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 114 | 43.5 | 194.1 | 13.2 | ||

| Lozoya | 62 | 48.9 | 105.6 | 15.1 | ||

| Montejo | 30 | 60.0 | 51.1 | 21.4 | ||

| Buitrago | 16 | 53.3 | 27.2 | 16.3 | ||

| Navafría | 46 | 34.1 | 78.3 | 11.0 | ||

| Riaza | 3 | 100.0 | 5.1 | 100 | ||

| Red deer | El Espinar | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 1 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 0.4 | ||

| Lozoya | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Montejo | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Buitrago | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Navafría | 1 | 0.7 | 5.0 | 0.7 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Wild boar | El Espinar | 1 | 25.0 | 4.3 | 45.9 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 1 | 50.0 | 4.3 | 71.7 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 106 | 40.5 | 457.8 | 31.2 | ||

| Lozoya | 28 | 22.0 | 120.9 | 17.3 | ||

| Montejo | 4 | 8.0 | 17.3 | 7.3 | ||

| Buitrago | 6 | 20.0 | 25.9 | 15.5 | ||

| Navafría | 67 | 49.6 | 289.4 | 40.7 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Mountain goat | El Espinar | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 4 | 1.5 | 13.3 | 0.9 | ||

| Lozoya | 3 | 2.4 | 10.0 | 1.4 | ||

| Montejo | 8 | 16.0 | 26.6 | 11.1 | ||

| Buitrago | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Navafría | 3 | 2.2 | 9.9 | 1.4 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Total | El Espinar | 2 | 50.0 | 6.0 | 64.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 2 | 100.0 | 6.0 | 100.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 225 | 85.9 | 670.2 | 45.7 | ||

| Lozoya | 93 | 73.2 | 236.5 | 33.8 | ||

| Montejo | 42 | 84.0 | 95.0 | 39.8 | ||

| Buitrago | 22 | 73.4 | 53.1 | 31.8 | ||

| Navafría | 117 | 86.6 | 382.6 | 53.8 | ||

| Riaza | 3 | 100.0 | 5.1 | 100.0 | ||

| Domestic ungulates | Cattle | El Espinar | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 22 | 8.4 | 770.9 | 52.5 | ||

| Lozoya | 12 | 9.4 | 420.5 | 60.0 | ||

| Montejo | 4 | 8.0 | 140.2 | 58.8 | ||

| Buitrago | 3 | 10.0 | 105.1 | 63.0 | ||

| Navafría | 9 | 6.7 | 315.3 | 44.3 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Domestic goat | El Espinar | 2 | 50.0 | 3.4 | 36.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 9 | 3.4 | 15.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Lozoya | 6 | 4.7 | 10.2 | 1.4 | ||

| Montejo | 1 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 0.7 | ||

| Buitrago | 4 | 13.3 | 6.8 | 4.1 | ||

| Navafría | 7 | 5.3 | 11.9 | 1.7 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sheep | El Espinar | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 6 | 2.3 | 10.7 | 0.7 | ||

| Lozoya | 5 | 3.9 | 8.9 | 1.3 | ||

| Montejo | 1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.7 | ||

| Buitrago | 1 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.1 | ||

| Navafría | 1 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.2 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Horse | El Espinar | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Lozoya | 1 | 0.9 | 24.8 | 3.5 | ||

| Montejo | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Buitrago | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Navafría | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Unidentified livestock | El Espinar | 0 | 0.0 | - | - | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | - | - | ||

| PN Peñalara | 0 | 0.0 | - | - | ||

| Lozoya | 10 | 7.9 | - | - | ||

| Montejo | 2 | 4.0 | - | - | ||

| Buitrago | 0 | 0.0 | - | - | ||

| Navafría | 1 | 0.7 | - | - | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | - | - | ||

| Total | El Espinar | 2 | 50.0 | 3.4 | 36.0 | |

| PRCAM Norte | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| PN Peñalara | 37 | 14.1 | 796.9 | 54.3 | ||

| Lozoya | 34 | 26.8 | 464.4 | 66.2 | ||

| Montejo | 8 | 16.0 | 143.7 | 60.2 | ||

| Buitrago | 8 | 26.6 | 113.8 | 68.2 | ||

| Navafría | 18 | 13.4 | 329.0 | 46.2 | ||

| Riaza | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

Percentage of occurrence of wild and domestic ungulates according to forest regions. Statistical results according to forest region comparing the consumption of domestic and wild ungulates.

| Forest region | Faecal samples collected (n) | % Wild ungulates occurrence | % Domestic ungulates occurrence |

Statistical results (wild vs domestic) |

| El Espinar | 4 | 50.0 | 50.0 | - |

| PRCAM Norte | 2 | 100.0 | 0.0 | - |

| PN Peñalara | 262 | 85.9 | 14.1 | χ2=134.90; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Lozoya | 127 | 73.2 | 26.8 | χ2=27.40; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Montejo | 50 | 84.0 | 16.0 | χ2=23.12; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Buitrago | 30 | 73.4 | 26.6 | χ2=6.53; df=1; p=0.11 |

| Navafría | 135 | 86.6 | 13.4 | χ2=72.6; df=1; p=0.001 |

| Riaza | 3 | 100.0 | 0.0 | - |

| Statistical results WYXYWX(wild species vs domestic species) | χ2=69.68; df=21; p=0.038, n=506 | χ2=30.94; df=20; p=0.065, n=107 | ||

References

- Keller, I.; Largiadèr, C.R. Recent Habitat Fragmentation Caused by Major Roads Leads to Reduction of Gene Flow and Loss of Genetic Variability in Ground Beetles. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, D. Using Spatial Indicators and Value Functions to Assess Ecosystem Fragmentation Caused by Linear Infrastructures. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinformation 2004, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancebo Quintana, S.; Martín Ramos, B.; Casermeiro Martínez, M.A.; Otero Pastor, I. A Model for Assessing Habitat Fragmentation Caused by New Infrastructures in Extensive Territories—Evaluation of the Impact of the Spanish Strategic Infrastructure and Transport Plan. J. Environ. Manage. 2010, 91, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullu, D. A Review on the Effect of Habitat Fragmentation on Ecosystem. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Laliberte, A.; Ripple, W. Range Contractions of North American Carnivores and Ungulates. Bioscience 2004, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybes, C.; Yalden, D. Mammal Review. 1995, pp. 201–227.

- Zlatanova, D.; Ahmed, A.; Vlasseva, A.; Genov, P. Adaptive Diet Strategy of the Wolf (Canis lupus L.) in Europe: A Review. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2014, 66, 439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Ripple, W.; Estes, J.; Beschta, R.; Wilmers, C.; Ritchie, E.; Hebblewhite, M.; Berger, J.; Elmhagen, B.; Letnic, M.; Nelson, M.; et al. Status and Ecological Effects of the World’s Largest Carnivores. Science 2014, 343, 1241484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvrier, J.; Duchamp, C.; Lauret, V.; Marboutin, E.; Cubaynes, S.; Choquet, R.; Miquel, C.; Gimenez, O. Mapping and Explaining Wolf Recolonization in France Using Dynamic Occupancy Models and Opportunistic Data. Ecography 2018, 41, 647–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, A.; Capitani, C.; Mattioli, L.; Apollonio, M. Livestock Damage and Wolf Presence. J. Zool. 2008, 274, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco Torres, R.; Silva, N.; Brotas, G.; Fonseca, C. To Eat or Not To Eat? The Diet of the Endangered Iberian Wolf (Canis lupus Signatus) in a Human-Dominated Landscape in Central Portugal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, M.R.; Sand, H.; Virgós, E. Promoting Grazing or Rewilding Initiatives against Rural Exodus? The Return of the Wolf and Other Large Carnivores Must Be Considered. Environ. Conserv. 2020, 47, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitani, L.; Linnell, J. Bringing Large Mammals Back: Large Carnivores in Europe. Rewilding Eur. Landsc. 2015, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, S.; Mysłajek, R.; Jedrzejewska, B. Patterns of Wolf Canis lupus Predation on Wild and Domestic Ungulates in the Western Carpathian Mountains (S Poland). Acta Theriol. (Warsz.) 2005, 50, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriggi, A.; Lovari, S. A Review of Wolf Predation in Southern Europe: Does the Wolf Prefer Wild Prey to Livestock? J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 1561–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S. Diet Composition of Wolves (Canis lupus) on the Scandinavian Peninsula Determined by Scat Analysis., School of Forest Science and Resource Management, Technical University of München, Germany., 2006.

- Ansorge, H.; Kluth, G.; Hahne, S. Feeding Ecology of WolvesCanis lupus Returning to Germany. Acta Theriol. (Warsz.) 2006, 51, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahler, D.R.; Smith, D.W.; Guernsey, D.S. Foraging and Feeding Ecology of the Gray Wolf (Canis lupus): Lessons from Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, USA. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1923S–1926S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daria Octenjak; Lana Pađen; Valentina Šilić; Slaven Reljić; Tajana Trbojević Vukičević; Josip Kusak Wolf Diet and Prey Selection in Croatia. Mammal Res. 2020, 65, 647–654. [CrossRef]

- Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation; Mech, L. D., Boitani, L., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, 2007; ISBN 978-0-226-51697-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lanszki, J.; Márkus, M.; Újváry, D.; Szabó, Á.; Szemethy, L. Diet of Wolves Canis lupus Returning to Hungary. Acta Theriol. (Warsz.) 2012, 57, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, T.; Boitani, L.; Chapron, G.; Ciucci, P.; Dickman, C.; Dellinger, J.; López-Bao, J.V.; Peterson, R.; Shores, C.; Wirsing, A.; et al. Food Habits of the World’s Grey Wolves. Mammal Rev. 2016, 46, n. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja, I. Prey and Prey-Age Preference by the Iberian Wolf Canis lupus Signatus in a Multiple-Prey Ecosystem. Wildl. Biol. 2009, 15, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlberg, S.; Bassi, E.; Viviani, V.; Apollonio, M. Quantifying Prey Selection of Northern and Southern European Wolves (Canis lupus). Mamm. Biol.—Z. Für Säugetierkd. 2016, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorovich, V.E.; Tikhomirova, L.L.; Jędrzejewska, B. Wolf Canis lupus Numbers, Diet and Damage to Livestock in Relation to Hunting and Ungulate Abundance in Northeastern Belarus during 1990–2000. Wildl. Biol. 2003, 9, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmers, C.C.; Post, E.; Hastings, A. The Anatomy of Predator-Prey Dynamics in a Changing Climate. J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewski, W.; Niedziałkowska, M.; Hayward, M.W.; Goszczyński, J.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Borowik, T.; Bartoń, K.A.; Nowak, S.; Harmuszkiewicz, J.; Juszczyk, A.; et al. Prey Choice and Diet of Wolves Related to Ungulate Communities and Wolf Subpopulations in Poland. J. Mammal. 2012, 93, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mech, L.D.; Fieberg, J. Re-Evaluating the Northeastern Minnesota Moose Decline and the Role of Wolves. J. Wildl. Manag. 2014, 78, 11431150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, A.; Lovari, S.; Khan, M.Z.; Mori, E. Sympatric Snow Leopards and Tibetan Wolves: Coexistence of Large Carnivores with Human-Driven Potential Competition. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2017, 63, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessing the Relationship between Illegal Hunting of Ungulates, Wild Prey Occurrence and Livestock Depredation Rate by Large Carnivores—Soofi—2019—Journal of Applied Ecology—Wiley Online Library Available online:. Available online: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2664.13266 (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Blanco, J.C.; Cuesta, L.; Reig, S. El Lobo (Canis lupus) En Espana. Situacion, Problematica y Apuntes Sobre Su Ecologia.; Madrid, 1990; p. 118.

- Cuesta, L.; Barcena, F.; Palacios, F.; Reig, S. The Trophic Ecology of the Iberian Wolf (Canis lupus signatus Cabrera, 1907). A New Analysis of Stomach’s Data. Mammalia 1991, 55, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, L.; Bárcena, F. Spatial Variability in Wolf Diet and Prey Selection in Galicia (NW Spain). Mammal Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaneza, L.; López-Bao, J.V. Indirect Effects of Changes in Environmental and Agricultural Policies on the Diet of Wolves. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2015, 61, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, G.; Kaczensky, P.; Linnell, J.; von Arx, M.; Huber, D.; Andrén, H.; López-Bao, J.V.; Adamec, M.; Álvares, F.; Anders, O.; et al. Recovery of Large Carnivores in Europe’s Modern Human-Dominated Landscapes. Science 2014, 346, 1517–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, Y.; Sgardelis, S.; Koutis, V.; Savaris, D. Wolf Depredation on Livestock in Central Greece. Mammal Res. 2009, 54, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nores, C.; González, F.; García, P. Wild Boar Distribution Trends in the Last Two Centuries: An Example in Northern Spain. IBEX J. Mt. Ecol. 1995, 3, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.; López-Bao, J.V.; Llaneza, L.; Álvares, F.; Lopes, S.; Blanco, J.C.; Cortés, Y.; García, E.; Palacios, V.; Rio-Maior, H.; et al. Cryptic Population Structure Reveals Low Dispersal in Iberian Wolves. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, A.; Bertelli, I.; Avanzinelli, E.; Tolosano, A.; Bertotto, P.; Apollonio, M. Predation by Wolves (Canis lupus) on Wild and Domestic Ungulates of the Western Alps, Italy. J. Zool. 2005, 266, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriggi, A.; Brangi, A.; Schenone, L.; Signorelli, D.; Milanesi, P. Changes of Wolf (Canis lupus) Diet in Italy in Relation to the Increase of Wild Ungulate Abundance. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2011, 23, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanesi, P.; Alberto, M.; Merli, E. Selection of Wild Ungulates by Wolves Canis lupus (L. 1758) in an Area of the Northern Apennines (North Italy). Ethol. Ecol. Evol.—ETHOL ECOL EVOL 2012, 24, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, N.F.; Álvares, F.; Ďurová, J.; Urban, P.; Bučko, J.; Iľko, T.; Brndiar, J.; Štofik, J.; Pataky, T.; Barančeková, M.; et al. What Drives Wolf Preference towards Wild Ungulates? Insights from a Multi-Prey System in the Slovak Carpathians. PloS One 2022, 17, e0265386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FernáNdez-Llario, P.; Carranza, J.; Mateos-Quesada, P. Sex Allocation in a Polygynous Mammal with Large Litters: The Wild Boar. Anim. Behav. 1999, 58, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcajada-Sánchez, F.; Barja, I. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Two Distance-Sampling Techniques for Monitoring Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus) Densities. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 2015, 52, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdmann, H.; Andersone-Lilley, Z.; Koppa, O.; Ozolins, J.; Bagrade, G. Winter Diets of WolfCanis lupus and LynxLynx Lynx in Estonia and Latvia. Acta Theriol. (Warsz.) 2005, 50, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbert, C.; Caniglia, R.; Fabbri, E.; Milanesi, P.; Randi, E.; Serafini, M.; Torretta, E.; Meriggi, A. Why Do Wolves Eat Livestock?: Factors Influencing Wolf Diet in Northern Italy. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 195, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucci, P.; Artoni, L.; Crispino, F.; Tosoni, E.; Boitani, L. Inter-Pack, Seasonal and Annual Variation in Prey Consumed by Wolves in Pollino National Park, Southern Italy. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2018, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Drummer, T.; Murphy, K.; Guernsey, D.; Evans, S. Winter Prey Selection and Estimation of Wolf Kill Rates in Yellowstone National Park, 1995-2000. J. Wildl. Manag. 2004, 68, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.; Reig, S.; Cuesta, L. Distribution, Status and Conservation Problems of the Wolf Canis lupus in Spain. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 60, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.C.; Cortés, Y. Ecología, Censos, Percepción y Evolución Del Lobo En España: Análisis de Un Conflicto. Sociedad Española Para La Conservación y Estudio de Los Mamíferos, Málaga, Spain. In Proceedings of the Sociedad Española para la Conservación y Estudio de los Mamíferos; Málaga; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, J.; Cortés, Y. Dispersal Patterns, Social Structure and Mortality of Wolves Living in Agricultural Habitats in Spain. J. Zool. 2007, 273, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouwborst, A. The EU Habitats Directive and Wolf Conservation and Management on the Iberian Peninsula: A Legal Perspective. Galemys Span. J. Mammal. 2014, 26, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibes-Mateos, M. Wolf Media Coverage in the Region of Castilla y León (Spain): Variations over Time and in Two Contrasting Socio-Ecological Settings. Animals 2020, 10, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espirito-Santo, C. Human Dimensions in Iberian Wolf Management in Portugal: Attitudes and Beliefs of Interest Groups and the Public toward a Fragmented Wolf Population. masters, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2007.

- Houston, M.; Bruskotter, J.; Fan, D. Attitudes Toward Wolves in the United States and Canada: A Content Analysis of the Print News Media, 1999–2008. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2010, 15, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bao, J.V.; Sazatornil, V.; Llaneza, L.; Rodriguez, A. Indirect Effects on Heathland Conservation and Wolf Persistence of Contradictory Policies That Threaten Traditional Free- Ranging Horse Husbandry. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redpath, S.M.; Gutiérrez, R.J.; Wood, K.A.; Sidaway, R.; Young, J.C. An Introduction to Conservation Conflicts. In Conflicts in Conservation: Navigating Towards Solutions; Cambridge University Press, 2015; pp. 3–18.

- Braña, F.; Campo, J.; Palomero, G. cta Biológica Montana. 1982, pp. 33–52.

- Salvador, A.; Abad, P.L. Food Habits of a Wolf Population (Canis lupus) in León Province, Spain. 1987, 51, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Urios, V.; Vila, C.; Bernáldez, E.; Delibes, M. Contribución al Conocimiento de La Alimentación Del Lobo Ibérico Canis lupus En La Sierra de La Culebra (Zamora). In Proceedings of the El lobo ibérico; Adm. Prov. Salamanca; pp. 47–56.

- Fernández, A.; Fernández, JM; Palomero, G. El lobo en Cantabria. Situación, problemática y apuntes sobre su ecología. 33–44.

- Barja, I.; de Miguel, F.J.; Bárcena, F. The Importance of Crossroads in Faecal Marking Behaviour of the Wolves (Canis lupus). Naturwissenschaften 2004, 91, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja, I.; de Miguel, F.; BÁRCENA, F. Faecal Marking Behaviour of Iberian Wolf in Different Zones of Their Territory. Folia Zool. -Praha- 2005, 54, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Steenweg, R.; Gillingham, M.; Parker, K.; Heard, D. Considering Sampling Approaches When Determining Carnivore Diets: The Importance of Where, How, and When Scats Are Collected. Mammal Res. 2015, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja, I. Decision Making in Plant Selection during the Faecal-Marking Behaviour of Wild Wolves. Anim. Behav. 2009, 77, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F.; Lovari, S.; Mancino, V.; Burrini, L.; Rossa, M. Food Habits of Wolves and Selection of Wild Ungulates in a Prey-Rich Mediterranean Coastal Area. Mamm. Biol. 2019, 99, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, I.B.; González, M.C.H.; Castilla, Á.N. Manual de los patrones macroscópicos y cuticulares del pelo en mamíferos de la península ibérica; UAM Ediciones, 2021.

- Zub, K.; Theuerkauf, J.; Jędrzejewski, W.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Schmidt, K.; Kowalczyk, R. Wolf Pack Territory Marking in the Białowieża Primeval Forest (Poland). Behaviour 2003, 140, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, R. SIG Aplicado à Segurança No Trânsito–Estudo de Caso No Município de Vitória–ES. Monogr. Apresentada Ao Dep. Geogr. UFES 2010.

- Kawamoto, M. Análise de Técnicas de Distribuição Espacial Com Padrões Pontuais e Aplicação a Dados de Acidentes de Trânsito e a Dados Da Dengue de Rio Claro-SP, Universidade Estadual Paulista Julio de Mesquita Filho, Instituto de Biociências de Botucatu, 2012.

- Rizzatti, M.; Batista, N.; Cezar Spode, P.; Bouvier Erthal, D.; Faria, R.; Scotti, A.; Trentin, R.; Petsch, C.; Turba, I.; Quoos, J. Mapeamento Da COVID-19 Por Meio Da Densidade de Kernel. Metodol. E Aprendizado 2020, 3, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Câmara, G. Análise de Eventos Pontuais. In Análise Espacial de Dados Geográficos; In: Druck S, Carvalho MS, Câmara G.; Monteiro AVM.: Brasília, EMBRAPA, 2004 ISBN 85-7383-260-6.

- BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Fundação Oswaldo Cruz. Introdução à Estatística Espacial para a Saúde Pública. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2007.

- Floyd, T.J.; Mech, L.D.; Jordan, P.A. Relating Wolf Scat Content to Prey Consumed. J. Wildl. Manag. 1978, 42, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.L. Refining the Equation for Interpreting Prey Occurrence in Gray Wolf Scats. J. Wildl. Manag. 1993, 57, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaneza, L.; Fernández, A.; Nores, C. Dieta Del Lobo En Dos Zonas de Asturias (España) Que Difieren En Carga Ganadera. Doñana Acta Vertebr. 1996, 23, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, A.; Valente, A.; Barros, T.; Carvalho, J.; Silva, D.; Fonseca, C.; Madeira de Carvalho, L.; Tinoco Torres, R. What Does the Wolf Eat? Assessing the Diet of the Endangered Iberian Wolf (Canis lupus Signatus) in Northeast Portugal. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutcheson, K. A Test for Comparing Diversities Based on the Shannon Formula. J. Theor. Biol. 1970, 29, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levins, R. Evolution in Changing Environments: Some Theoretical Explorations. (MPB-2) (Monographs in Population Biology, 2)—Levins, Richard: 9780691080628—AbeBooks; Princeton University Press, 1968.

- Jacobs, J. Quantitative Measurement of Food Selection. Oecologia 1974, 14, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urios, V. Eto-Ecología de La Depredación Del Lobo Canis lupus Signatus En El NO de La Península Ibérica. PhD Thesis, Tesis doctoral. Universidad de Barcelona, 1995.

- Blanco, J.C. Mamíferos de España; Planeta, 1998.

- Mateos-Quesada, P. Biología y Comportamiento Del Corzo Ibérico; Universidad de Extremadura, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2002.

- Wagner, C.; Holzapfel, M.; Kluth, G.; Reinhardt, I.; Ansorge, H. Wolf (Canis lupus) Feeding Habits during the First Eight Years of Its Occurrence in Germany. Mamm. Biol. 2012, 77, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, M.; DAGRADI, V.; Dondina, O.; PERVERSI, M.; Milanesi, P.; LOMBARDINI, M.; RAVIGLIONE, S.; REPOSSI, A. Short-Term Responses of Wolf Feeding Habits to Changes of Wild and Domestic Ungulate Abundance in Northern Italy. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, E.; Benatti, L.; Lovari, S.; Ferretti, F. What Does the Wild Boar Mean to the Wolf? Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2017, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, C.; Herrero, J. Sus Scrofa Linnaeus, 1758. Atlas Libro Rojo Los Mamíferos Esp. Dir. Gen. Para Biodivers.-SECEM-SECEMU Madr. 2007, 348–351.

- Fonseca, C.; Correia, F. Fonseca C, Correia F (2008). O Javali. Colecção Património Natural Transmontano. João Azevedo Editor (1.a Edição). Mirandela.; 2008; p. 168.

- Giménez-Anaya, A.; Bueno, C.G.; Fernández-Llario, P.; Fonseca, C.; García-González, R.; Herrero, J.; Nores, C.; Rosell, C. What Do We Know About Wild Boar in Iberia. In Problematic Wildlife II; Angelici, F.M., Rossi, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-42334-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, C.; Muñoz, A.; Navàs, F.; Fernández-Bou, M.; Sunyer, P.; Bonal, R.; Espelta, J.M. Principals Resultats Del Projecte “Impactboar” de Seguiment de l’activitat Del Senglar al Parc Nacional d’Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici. X Jornades Sobre Recer. Al Parc Nac. D’Aigüestortes Estany St. Mauric Dep. Territ. Sostenibilitat–Parc Nac. D’Aigüestortes Estany St. Maurici 2016, 209–218.

- Horcajada-Sánchez, F.; Barja, I. Local Ecotypes of Roe Deer Populations (Capreolus Capreolus L.) in Relation to Morphometric Features and Fur Colouration in the Centre of the Iberian Peninsula. Pol. J. Ecol. 2016, 64, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, L.; Capitani, C.; Gazzola, A.; Scandura, M.; Apollonio, M. Prey Selection and Dietary Response by Wolves in a High-Density Multi-Species Ungulate Community. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2011, 57, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Quesada, P.; Carranza, J. Reproductive Patterns of Roe Deer in Central Spain. Etología 2000, 8, 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, T.K.; Mech, L.D.; Cochrane, J.F. Wolf Population Dynamics. Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Univ. Chic. Press Chic. IL USA Pac. Clim. Eff. Ungulate Recruit. 2003, 481, 161–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kirilyuk, A.; Kirilyuk, V.; Minaev, A. Daily Activity Patterns of Wolves in Open Habitats in the Dauria Ecoregion, Russia. Nat. Conserv. Res. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromsigt, J.P.G.M.; Kuijper, D.P.J.; Adam, M.; Beschta, R.L.; Churski, M.; Eycott, A.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Mysterud, A.; Schmidt, K.; West, K. Hunting for Fear: Innovating Management of Human-Wildlife Conflicts. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, H.M.; Webb, N.F.; Merrill, E.H. Hierarchical Predation: Wolf (Canis lupus) Selection along Hunt Paths and at Kill Sites. Can. J. Zool. 2012, 90, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, E.; Caviglia, L.; Serafini, M.; Alberto, M. Wolf Predation on Wild Ungulates: How Slope and Habitat Cover Influence the Localization of Kill Sites. Curr. Zool. 2017, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prey occurrence | Ingested biomass | Prey mean mass (Kg) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prey | N | % | Kg | % | Adult | Youth | Mean | |

| Wild ungulates | Roe deer | 233 | 34.7 | 500.7 | 13.8 | 24.5 | 7.0 | 15.8 |

| Red deer | 2 | 0.3 | 10.1 | 0.3 | 90.0 | 25.0 | 57.5 | |

| Wild boar | 294 | 43.9 | 1006.3 | 27.7 | 75.0 | 22.0 | 48.5 | |

| Mountain goat | 21 | 3.1 | 69.7 | 1.9 | 61.0 | 11.0 | 36.0 | |

| Total | 550 | 82.0 | 1586.7 | 43.7 | ||||

| Domestic ungulates | Cattle | 55 | 8.2 | 1927.2 | 53.0 | 750.0 | 115.0 | 432.5 |

| Domestic goat | 28 | 4.2 | 47.5 | 1.3 | 26.3 | 5.0 | 15.7 | |

| Sheep | 15 | 2.2 | 26.8 | 0.7 | 28.5 | 5.0 | 16.8 | |

| Horse | 2 | 0.3 | 49.7 | 1.3 | 550.0 | 60.0 | 305.0 | |

| Unidentified livestock | 21 | 3.1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total | 121 | 18.0 | 2051.0 | 56.3 | ||||

| Total | 671 | 100.0 | 3637.8 | 100.0 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).