Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Wolf-Deterrent Collar

2.4. Retrospective and Progressive Data Comparison and Analysis

2.5. Camera Trapping

3. Results

3.1. Predation Events in the Three Trail Groups

3.2. Retrospective Analysis of Predation Losses (2020–2024)

3.3. Camera Trap Monitoring of Wolf Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Influences on Acoustic Deterrent Performance

4.2. Efficacy of Combined Protective Strategies

4.3. Perspectives and Work in Progress

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Ethical Considerations

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

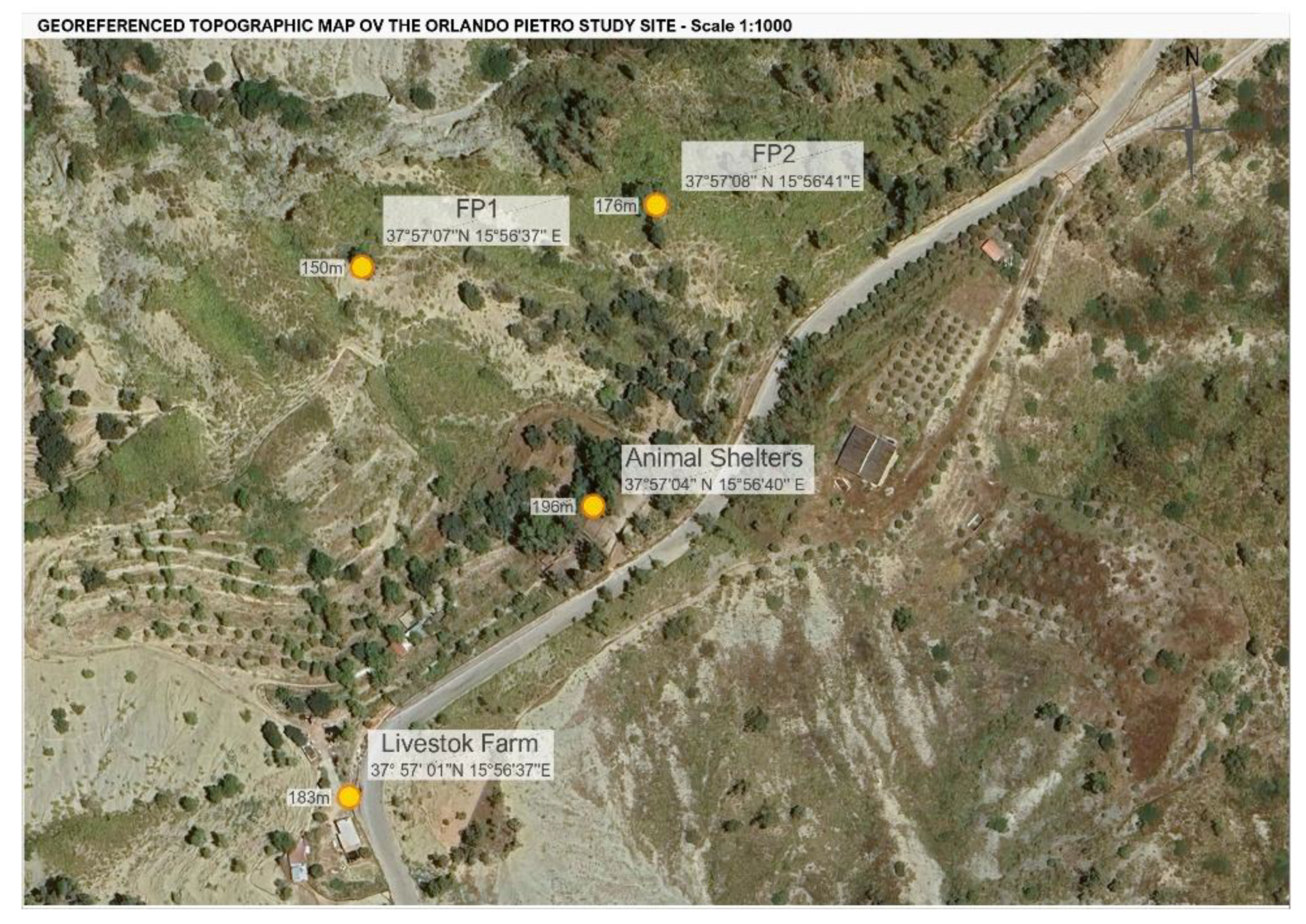

| FP1 | Camera Traps 1 |

| FP2 | Camera Traps 2 |

| PC | Group Experienced Herder Only |

| PCG | Group Herder and Guardian Dogs |

| PCGC | Group Herder + Guardian Dogs + Anti-Wolf Collar |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Parameter | Value / Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 200 m a.s.l. | According to Italian Geographic Military Institute (2023) |

| Coordinates | 37°57′01″ N, 15°56′37″ E | WGS84 system |

| Climate type | Mediterranean | Hot, dry summers; mild, wet winters |

| Annual mean temperature | 9 °C to 31 °C | Peaks ~34 °C in summer, rarely <6 °C in winter |

| Annual precipitation | ≈ 545 mm | Mostly concentrated in winter months |

| Warm season | mid-June to mid-September | Daily mean temperatures >28 °C |

| Cool season | late November to early April | Mean temperatures <18 °C |

| Peak solar radiation | July | Clear/partly cloudy skies ~96% of the time |

| Average wind speed | 13–21 km/h | Seasonal variability can affect sound propagation |

| Relative humidity | Variable | Seasonally dependent; relevant for acoustic systems |

References

- Boitani, L. Wolf conservation and recovery. Carnivore Conserv. 2003, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marucco, F.; Pletscher, D.H.; Boitani, L.; Schwartz, M.K.; Pilgrim, K.L.; Lebreton, J.D. Wolf survival and population trend using non-invasive capture–recapture techniques in the Western Alps. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 49, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucci, P.; Boitani, L. Wolf and dog depredation on livestock in central Italy. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 1998, 26, 504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Pittarello, M.; Carmignani, L.; Argenti, G.; Tardella, F.M. Livestock grazing and biodiversity conservation: Can they coexist in a Mediterranean context? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 277, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, G.; Bartolomé, J.; Bergmeier, E.; Bielsa, A.; Bugalho, M.N.; De Vries, F.; Plieninger, T. High Nature Value farming systems in Europe: Types, characteristics and policy support; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Cretois, B. Research for AGRI Committee-The revival of wolves and other large predators and its impact on farmers and their livelihood in rural regions of Europe; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. State of Nature in the EU: Results from Reporting under the Nature Directives 2013–2018; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ISMEA. Report on Italian Animal Husbandry 2023; Institute of Services for the Agricultural Food Market: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. Canis lupus: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ripple, W.J.; Estes, J.A.; Beschta, R.L.; Wilmers, C.C.; Ritchie, E.G.; Hebblewhite, M.; Schmitz, O.J. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science 2014, 343, 1241484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Europe. Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. Convention n. 104, Bern, Switzerland, 19 September 1979; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1979.

- UNEP-WCMC. CITES Trade Database – Canis lupus; United Nations Environment Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Centre: Cambridge, UK, 2023.

- European Commission. Natura 2000 and the Habitats Directive. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/natura-2000_en (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- European Council. Report on large carnivore populations and their management in Europe; European Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. EU funding for biodiversity and wildlife conservation: State of play; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ciucci, P.; Boitani, L. The return of the wolf: Strategies for coexistence. WWF: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Apollonio, M.; De Marinis, A. M.; Boitani, L. Wildlife and human activities. Pacini Publisher: Pisa, Italy, 2015, pp. 20-44.

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Odden, J.; Smith, M.E.; Aanes, R.; Swenson, J.E. Large carnivores that kill livestock: Do “problem individuals” really exist? Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2012, 30, 382–392. [Google Scholar]

- Espuno, N.; Lequette, B.; Poulle, M. L.; Migot, P.; Lebreton, J. D. Heterogeneity in wolf pack size and implications for depredation management. Ecological Modelling 2004, 180, 451–464. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori, V.; Mertens, A. Damage prevention methods in Europe: Experiences from LIFE Nature projects. Hystrix Ital. J. Mammal. 2012, 23, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, R. Livestock guarding dogs: Their current use worldwide; IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group: Gland, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gehring, T. M.; VerCauteren, K. C.; Landry, J. M. Utility of livestock-protection dogs for reducing predation on domestic sheep. Hum. Wildl. Interact. 2010, 4, 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.H. Defenses against visually hunting predators. In Perspectives in Ethology; Bateson, P.H., Klopfer, P.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 1, pp. 225–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, S.L.; Dill, L.M. Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: A review and prospectus. Can. J. Zool. 1990, 68, 619–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruuk, H. The Spotted Hyena: A Study of Predation and Social Behavior; Wildlife Behavior and Ecology series; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, R. J.; Blanchard, D. C.; Rodgers, J.; Weiss, S. M. The characterization and modelling of antipredator defensive behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2001, 25, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfelbach, R.; Blanchard, C. D.; Blanchard, R. J.; Hayes, R. A.; McGregor, I. S. The effects of predator odors on mammalian prey species: A review of field and laboratory studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005, 29, 1123–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, M. Defence in Animals: A Survey of Anti-Predator Defences. Longman: London, UK, 1974.

- Shivik, J.A.; Treves, A.; Callahan, P. Nonlethal techniques for managing predation: Primary and secondary repellents. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivik, J.A.; Martin, D.; Lutman, M. The use of conditioning stimuli to modify coyote predatory behavior. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 82, 195–211. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, P. J.; Mullet, C.; Gentle, M. N. Testing the efficacy of an ultrasonic device for excluding dingoes (Canis lupus dingo) from a resource. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2006, 7, 239–242. [Google Scholar]

- Götz, T.; Janik, V.M. Acoustic deterrent devices to prevent pinniped depredation: Efficiency, conservation concerns and possible solutions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2013, 492, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treves, A.; Karanth, K.U. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson-Nelson, S.; Gehring, T. M. Testing fladry as a non-lethal management tool for wolves in Michigan. Hum.-Wildl. Interact. 2010, 4, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.L.; Heffner, R.S. Auditory brainstem responses and sound localization in dogs (Canis familiaris). Behav. Neurosci. 1994, 108, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, R.S.; Heffner, H.E. Hearing ranges of laboratory animals. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2010, 49, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Strain, G.M. The basics of audiology for the canine practitioner. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2012, 42, 1099–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, H.E. Auditory sensitivity. In Encyclopedia of the Human Brain; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Krahé, C.; Taborsky, B.; Trillmich, F. Hearing abilities and auditory perception in livestock: A review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 214, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, R. S. Auditory awareness in domestic animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci.4 1998, 57, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDPI. Bioacoustic study of Indian wolf vocalizations. Animals 2022, 12, 631. [Google Scholar]

- Military Geographic Institute. Topographic map and geographic coordinates of the Italian territory. Military Geographic Institute Italy, 2023.

- Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies. List of disadvantaged areas and areas subject to natural or specific constraints pursuant to Regulation (EU) N° 1305/2013. Available online: https://www.politicheagricole.it/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Sevi, A.; Taibi, L.; Albenzio, M.; Muscio, A.; Dell’Aquila, S. Influence of parity and body condition score on colostrum quality and passive immunity in goat kids. Small Rumin. Res. 2001, 41, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Celi, P.; Di Trana, A.; Claps, S. Effects of different farming systems on immune response, oxidative stress, and metabolic profile in goats. Vet. J. 2008, 177, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Council Regulation (EC) No 21/2004 of 17 December 2003 on the identification and registration of animals kept for farming purposes. Official Journal of the European Union, L 5, 8 January 2004, pp. 8–17. Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2009.

- Gehring, T. M.; VerCauteren, K. C.; Landry, J. M. Livestock protection dogs in the 21st century. Biol. Conserv 2010, 142, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, P. B.; Hughes, N. K. A review of the evidence for the effectiveness of acoustic deterrents in reducing human–wildlife conflict. Mammal Rev. 2012, 42, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, G.S.A.; Vongraven, D.; Wilson, R.P. Bioacoustic deterrents for carnivore conflict mitigation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 247, 108577. [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor, K. M.; Brown, J. S.; Middleton, A. D.; Power, M. E.; Brashares, J. S. The influence of natural sounds on predator-prey interactions: Insights from acoustic ecology. Ecol. Lett. 2019, 22, 784–795. [Google Scholar]

- Zanette, L.; White, A.; Allen, M.; Clinchy, M. Use of acoustic signals to deter predators in wildlife management. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 912–921. [Google Scholar]

- Linnell, J.D.C.; Salvatori, V.; Boitani, L.; Ciucci, P. Managing human–carnivore conflicts: A review. Mammal Rev. 2020, 50, 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatori, V.; Mertens, A. Damage prevention methods in Europe: Experiences from LIFE Nature projects. Hystrix Ital. J. Mammal. 2012, 23, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kays, R.; Tilak, S.; Kranstauber, B.; Jansen, P.A.; Carbone, C.; Rowcliffe, M.; He, Z. Camera traps as sensor networks for monitoring animal communities. Int. J. Res. Rev. Wirel. Sens. Netw. 2011, 1, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, A.F.; Nichols, J.D.; Karanth, K.U. Camera traps in animal ecology: Methods and analyses; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meek, P.D.; Ballard, G.; Claridge, A. Camera traps-A review of methods and applications in wildlife ecology. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczensky, P.; et al. Livestock guarding dogs: The human–carnivore conflict mediator. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 184, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, H. E.; Sutherland, L. C.; Zuckerwar, A. J.; Blackstock, D. T.; Hester, D. M. Atmospheric absorption of sound: Update. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1995, 97, 680–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, T. F. W. Tutorial on sound propagation outdoors. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1996, 100, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomons, E.M. Computational Atmospheric Acoustics; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 9613-2. Acoustics-Attenuation of sound during propagation outdoors-Part 2: General method of calculation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- Ostashev, V.E.; Wilson, D.K. Acoustics in Moving Inhomogeneous Media; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Attenborough, K.; Li, K. M.; Horoshenkov, K. V. Predicting Outdoor Sound. CRC Press: London, 2007, pp. 251-350.

- Basten, T. G. H.; de Bree, H.-E.; van der Wal, N. J. Environmental influences on acoustic monitoring systems. Acta Acust. united Acust. 2015, 101, 741–751. [Google Scholar]

- Musiani, M.; Mamo, C.; Boitani, L.; Callaghan, C.; Gates, C.C.; Mattei, L.; Visalberghi, E.; Breck, S.; Volpi, G. Wolf depredation trends and the use of fladry barriers to protect livestock in western North America. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 1538–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCowan, B.; Anderson, K.; Heagerty, A.; Lefebvre, L. Effects of auditory enrichment on the behavior and welfare of laboratory animals. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 76, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hopster, H. The effect of music on animal behavior and welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2002, 76, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarczyk, R.; Ruczyński, I. Effects of traditional folk instruments sounds on animal behavior. Ethology 2020, 126, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, C. M. Welfare of sheep: Providing for welfare in an extensive environment. Small Rumin. Res. 2009, 86, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; De Rosa, G.; Grasso, F.; Braghieri, A. Animal welfare and productivity in sheep. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 18, 784–793. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, A.M.; Peake, T.M.; McGregor, P.K. The role of acoustic communication in animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 240, 105328. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, R.; et al. Effects of acoustic deterrents on livestock: Stress and productivity assessments. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2021, 24, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rushen, J.; de Passillé, A.M.; Munksgaard, L.; Jensen, M.B. The scientific assessment of animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, J. L.; Prieto, C. Effects of stress on livestock: Identification and mitigation. Livest. Sci. 2009, 124, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, T. Animal welfare and society concerns finding the missing link between animal behavior and welfare. Animals 2014, 4, 392–410. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Transhumance, the seasonal droving of livestock along migratory routes in the Mediterranean and in the Alps. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/transhumance-the-seasonal-droving-of-livestock-along-migratory-routes-in-the-mediterranean-and-in-the-alps-01470.

- European Commission. Guidance on the application of the Environmental Impact Assessment Directive. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eia/eia-guidelines/guidance_en.htm (accessed on 27 July 2025).

| Feature / Parameter |

Wolf (Canis lupus) | Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) |

Livestock (sheep, goats, cattle, horses) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing range (Hz) | ~150–45,000 Hz (up to ~80,000 Hz in some sources) [36,40] | ~67–45,000 Hz [37] | ~23–40,000 Hz, depending on species [38,39] |

| Peak sensitivity (Hz) | ~2,000–8,000 Hz (behaviorally); ~40,000–80,000 Hz (physiologically) [40] | ~2,000–8,000 Hz (behaviorally); ~1,000–20,000 Hz [37] | ~8,000–10,000 Hz (sheep/goats: ~10 kHz; cattle: ~8 kHz); ~1,000–8,000 Hz [38] |

| Ultrasound detection | Excellent; highly sensitive to ultrasonic range (up to 80 kHz) [36] | High; upper limit ~60 kHz [37] | Poor above ~20 kHz; limited response near 30–40 kHz [39] |

| Sensitivity level | Very high; adapted for long-distance detection and hunting | High, but variable across breed, age, and training | Moderate; suited to mid-frequency group alertness |

| Communication frequencies | ~150–780 Hz (howls) with higher harmonics [41] | Wide repertoire: barking, whining, growling [37] | Mostly low-frequency vocalizations: bleats, moos, neighs [40] |

| Functional implication | Detection of prey, predators, and conspecific calls; social communication | Responsive to human cues and high-frequency commands | Adapted for herd alertness; limited reliance on high-frequency acoustic signals |

| Adaptation | Wild hunter: optimized for survival, navigation, and territorial vocalizations | Domestic adaptation: tuned to canine–human communication | Domesticated herd species: optimized for inter-individual contact and predator detection |

| Components | Technical and Functional Specifications |

|---|---|

| Collar Material | Technical plastic filaments (high thermal and mechanical resistance, low conductivity) |

| Manufacturing Technology | 3D printing |

| Speakers | 2 piezoelectric POFET, 30 Vp-p, range 2.5 Hz–60 kHz, 14.07 watts |

| Generator Module | Kemo M048N, adjustable 7–40 kHz, max intensity 110 dB |

| Operating Frequency | 2.5 Hz–40 kHz |

| Power Supply Module | 12 V solar panel (1.5 W) + 150 Ah rechargeable lithium-ion battery |

| Energy Autonomy | 12 hours per day, up to 4 days without solar irradiation |

| Effective Range | Approximate useful radius of 50–100 meters, corresponding to 7,850–31,400 m2 (variable based on topography, morphology, and climate) |

| Emission System | Modulated intervals of frequencies based on natural harmonic sounds |

| Group | Livestock Category |

Month | Attacks | Prey | FP1(photos) | FP2 (photos) | Total Photos | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | Goats | June | 21 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 11 | Constant nocturnal presence |

| PC | Goats | July | 24 | – | 4 | 6 | 10 | Filmed episode |

| PC | Goats | August | 27 | – | 8 | 3 | 11 | Constant nocturnal presence |

| PCG | Goats | June | 11 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 9 | Wolf passages |

| PCG | Goats | July | 17 | – | 7 | 6 | 13 | Increased activity at dusk |

| PCG | Goats | August | 25 | – | 6 | 4 | 10 | Observed pair movement |

| PCGC | Goats | June | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 11 | Constant nocturnal presence |

| PCGC | Goats | July | 1 | – | 6 | 5 | 11 | Presence confirmed by video |

| PCGC | Goats | August | 0 | – | 5 | 5 | 10 | Observed pair movement |

| Year | Goats on Farm | Goats Predated by Wolf | Percentage | Total Stock |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 97 | 16 | 16 % | 81 |

| 2021 | 101 | 11 | 10 % | 98 |

| 2022 | 137 | 27 | 19 % | 110 |

| 2023 | 236 | 39 | 16 % | 197 |

| 2024 | 205 | 55 | 26 % | 150 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).