4.2. Species Accounts

4.2.1. Neoponera bugabensis (Forel, 1899)

Figures. 1b (head ☿); 13, 15, 16: a – c (☿); 14, 17: a – c (♀︎); 30a (distribution)

Pachycondyla theresiae var. bugabensis Forel, 1899: 14. ☿ lectotype [by designation of Mackay & Mackay, 2010: 224], Panama, Bugaba, Champion [leg.], (MHNG, AntWeb: CASENT0907242) [image examined, link].

Combinations. In Pachycondyla: Brown, 1995: 303; in Neoponera: Emery, 1901: 47; Schmidt and Shattuck, 2014: 151.

Subspecies of Neoponera theresiae: Emery, 1911: 72; Kempf 1972: 162; Bolton 1995: 303; Mackay, 2008: 198.

Status as species: MacKay and Mackay, 2010: 224 (redescription).

Worker and queen diagnosis. Head subquadrate (Figures 14b, 17b), sometimes slightly longer than broad (Fig. 15b), with longitudinal, weakly to well-impressed, irregular striae (Figs. 16b, 17b); antennal scape, when pulled posterad, exceeding posterior head margin by approximately 1.5 times (Figs. 14b, 16b) to 3 times (Fig. 15b) apical scape width; malar carina well-marked, it usually fades away before reaching anterior eye margin; humeral carina present, slightly salient; posterolateral margin of propodeum weakly carinate (Figs. 15a, 16a) or without carina; anterior margin of petiolar node either slightly inclined posterad (Figs. 8a, 10b) or steeper (Fig. 17a); posterolateral margin of node weakly carinate, carina usually blunt (Figs. 10b, 14a) mostly in Central American populations; anterior margin of node straight (Figs. 10b, 14a, 15a, 16a) or slightly concave, this latter only seen in queens from South America (Fig. 17a); dorsal appressed pilosity varying from pale yellowish-brownish (Fig. 16), to intense, brilliant golden (Figs. 14, 15), erect and suberect hairs on head and mesosomal dorsum either shorter or about as long as maximum eye length.

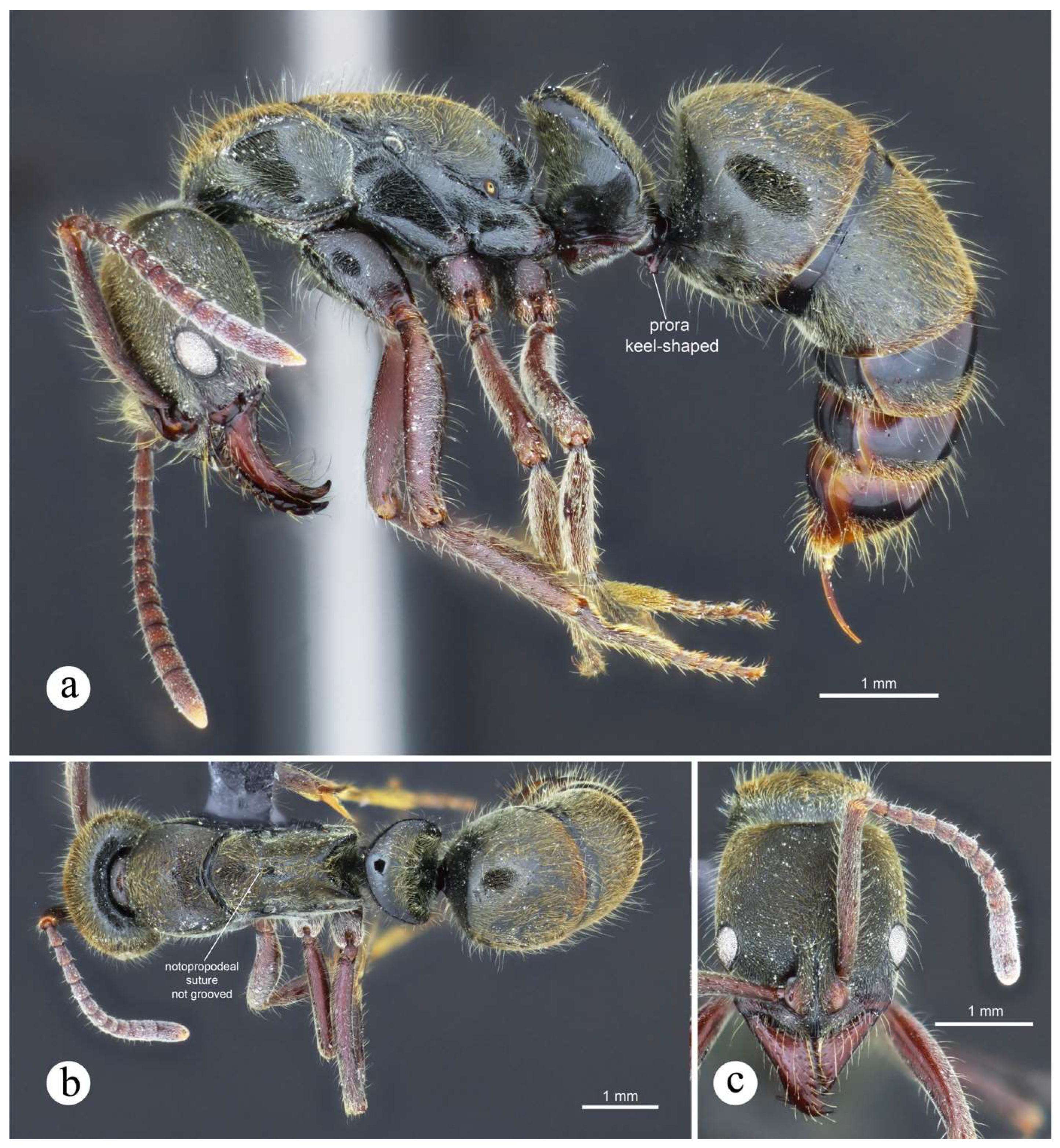

Figure 13.

Neoponera bugabensis. ☿ (MUCR: CASENT0637852), Costa Rica: Limón. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 13.

Neoponera bugabensis. ☿ (MUCR: CASENT0637852), Costa Rica: Limón. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 14.

Neoponera bugabensis. ♀︎ (JTLC: CASENT0617486), Honduras: Comayagua. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 14.

Neoponera bugabensis. ♀︎ (JTLC: CASENT0617486), Honduras: Comayagua. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 15.

Neoponera bugabensis_var1. ☿ (MUSENUV: MUSENUV22595), Colombia: Valle del Cauca. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 15.

Neoponera bugabensis_var1. ☿ (MUSENUV: MUSENUV22595), Colombia: Valle del Cauca. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 16.

Neoponera bugabensis_var2. ☿ (MUSENUV: HOR0985), Colombia: Valle del Cauca. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 16.

Neoponera bugabensis_var2. ☿ (MUSENUV: HOR0985), Colombia: Valle del Cauca. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 17.

Neoponera bugabensis_var2. ♀︎ (MUSENUV: HOR0983), Colombia: Valle del Cauca. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 17.

Neoponera bugabensis_var2. ♀︎ (MUSENUV: HOR0983), Colombia: Valle del Cauca. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Worker. Measurements (n = 14): HW: 1.73-2.1; HL: 2.02-2.45; EL: 0.5-0.65; SL: 1.72-2.7; WL: 3.15-3.8; PrW: 1.25-1.55; MsW: 0.76-0.95; MsL: 0.63-0.88; PW: 0.9-1.15; PH: 0.6-1.2; PL: 0.9-1.25; GL: 3.29-4.7; A3L: 1.18-1.5; A4L: 1.23-1.7; A3W: 1.4-1.7; A4W: 1.45-1.75; TLa: 8.49-10.7; TLr: 9.61-11.68. Indices. CI: 79.35-88.64; OI: 28.21-34.29; SI: 97.56-131.71; MsI: 105.71-123.33; LPI: 91.67-150.0; DPI: 80.0-111.11.

Queen. Measurements (n = 6): HW: 1.84-2.31; HL: 2.23-2.69; EL: 0.59-0.72; SL: 1.98-2.45; WL: 3.65-4.44; PrW: 1.45-1.81; MsW: 1.33-1.69; MsL: 1.3-2.25; PW: 1.04-1.2; PH: 1.02-1.25; PL: 1.1-1.28; GL: 4.2-5.5; A3L: 1.45-1.8; A4L: 1.6-1.95; A3W: 1.61-2.0; A4W: 1.69-2.12; TLa: 10.14-11.91; TLr: 11.21-13.91. Indices. CI: 82.0-90.2; OI: 29.27-33.68; SI: 95.65-121.28; MsI: 73.91-111.54; LPI: 97.78-109.52; DPI: 92.68-104.35.

Male. Described by MacKay and Mackay (2010).

Comments. Neoponera bugabensis is a medium-sized taxon in the N. foetida group (Fig. 12; ☿: TLa = 8.5 – 10.7 mm; ♀︎TLa: 10.1 – 11.9 mm). Populations of Central America have a cuticle with more intense golden pilosity than those from South America, and are amongst the most brilliant in the genus when light is directed to their cuticle. In a similar fashion to N. curvinodis, the examined material of N. bugabensis shows relatively large size variation as judged by the variable TLa in workers (Fig. 12). In addition, some body traits also show variations somewhat correlated with geographic distribution making this species one of the most hard-to-diagnose in the genus together with N. curvinodis.

Based on the below variations, this species can be categorized under three forms: the first matches the traits of the lectotype from Panama, thus this is the “true” N. bugabensis (Figs. 13, 14), and is the most widely distributed form. The other two, which here are called “variant – 1” (Fig. 15), and “variant – 2” (Figs. 16, 17), are more restricted to Costa Rica and to Colombia-Ecuador, respectively. These variants slightly differ from N. bugabensis in the form of the head, petiolar node, pilosity and color. Difference in scape length between N. bugabensis and its variant – 2 was also noticed, but it was not consistent across all individuals. Despite this, they are not described as new in this work since such traits, except for scape length, show some degree of plasticity in other species of the genus, for example, in N. crenata (Roger), N. curvinodis (Forel), N. oberthueri (Emery), N. rugosula Emery. On the other hand, the current specimen-set available for each variant: 5 specimens from Costa Rica belonging to variant – 1, and 5 specimens from Colombia-Ecuador belonging to variant – 2, is not representative enough to detect a putative case of lineage divergence as judged from a pattern of morphological discontinuities departing from the traits characterizing N. bugabensis.

No doubt, this is a “tricky species”, it may just be a highly variable form composed of ecotypes which are in process of adaptive speciation, or it may be a multi-species-in-one case for which morphological analysis alone is insufficiently informative. DNA sequencing may aid, but also increasing the specimen-set representing the whole known distribution is required. In Neoponera, a similar example occurring in this transitional region, i.e., southern Central America and northern South America, is possibly depicted by the gradation of striae on the petiolar node in N. mashpi Troya and Lattke populations: those from Central America show a tenuous nodal sculpture which is more clearly impressed in populations from South America (Troya and Lattke 2022).

The reader may use the following characters to distinguish these two variants from N. bugabensis. In parentheses are given the differential traits for the latter.

Variant – 1: 1) Head longer than broad in frontal view (vs. quadrate to subquadrate). 2) Antennal scape, when pulled posterad, exceeding posterior head margin by 2 – 2.5 times apical scape width (vs. 1.5 – 2 times). In a specimen from Valle del Cauca, Colombia (MUSENUV22595) the scape is even longer, exceeding said head margin by ca. 3 times apical scape width. 3) Petiolar node longer than high in lateral view (vs. relatively more symmetric). 4) Most erect hairs on body dorsum longer than maximum eye length (vs. mostly shorter).

Variant – 2. This form is very similar to variant – 1, including the head shape, antennal scape length, and length of erect hairs. The following characters, however, distinguish it from N. bugabensis: 1) Appressed pilosity pale yellowish, and that of gastral dorsum not entirely covering the integument (vs. intense golden and usually completely covering gastral integument). 2) Carina of dorsolateral margin of petiolar node relatively acute, somewhat similar to that in N. insignis (vs. blunt carina on dorsolateral nodal margin).

Neoponera bugabensis could be confused with the following five species in the N. foetida group: N. insignis (including the variant “villosa_cf2”), N. lineaticeps, N. theresiae, N. prasiosomis sp. nov., N. villosa. Of these, arguably N. insignis is very close phylogenetically to N. bugabensis (Troya et al. unpublished). Neoponera insignis and N. bugabensis occur in sympatry, at least in Costa Rica (Longino 2010), and N. villosa_cf2 is known from a single specimen from Darien, Panama. According to Longino (2010), and Mackay and Mackay (2010), N. insignis is identical to N. bugabensis, and these differ in the striae orientation of the mid clypeus: transverse on the former, and longitudinal in the latter. However, among the material examined, three specimens of N. insignis, a worker and queen from Parque Nacional Katios, Colombia (LACMENT142417), and a worker from Darién, Panama (JTL9077-1), carry longitudinal striae on the mid clypeus. This is another evidence supporting the hypothesis that clypeal striae are a plastic trait in Neoponera and should not be used in species diagnoses. Further evidence is presented under the treatment of N. curvinodis (see below), where more examples of clypeal striae variations are brought together for other species in the genus. Neoponera insignis is indeed nearly indistinguishable from N. bugabensis. The following features are helpful: 1) The head of N. insignis, as measured horizontally from eye to eye, is slightly broader than that of N. bugabensis, and apparently, as inferred from the few specimens examined (n = 4 ☿, 2♀) from Colombia, Costa Rica, and Panama, the eye does not break- but just reaches, or at most feebly exceeds the lateral head margin. In N. bugabensis the eye always exceeds such margin. 2) The antennal scape of N. insignis, when pulled posterad, exceeds the posterior head margin by one- or at most 1.5 times the apical scape width, while in N. bugabensis it always exceeds that margin by 1.5 up to 3 times the apical scape width. 3) The dorsoposterior nodal margin in N. insignis is carinate, with the carina relatively acute. In N. bugabensis that margin is usually blunt, especially in the Central American specimens, but apparently this is not always the case in populations from South America. Two queens from Ecuador, for example, one from Esmeraldas (MEPN38311), a site from the Chocó-Darién, and another from the Amazonian Parque Nacional Yasuní (MEPN34643) show a slightly acute nodal margin, less so however, than in N. insignis.

Neoponera lineaticeps is easily distinguishable from N. bugabensis just by examining the dorsum of head and the dorsoposterior nodal face which carry well-impressed longitudinal striae, especially those on head (Fig. 4a) which may also be referred as costae since these are thicker than those on the node. These striae (or costae) are absent in N. bugabensis.

Neoponera theresiae is distinguished from N. bugabensis in: 1) Showing longitudinally divergent striae on the proximal region of the mandibular dorsum (Fig. 6a). Neoponera bugabensis also bears striae on such region but these are significantly more attenuated. 2) Well-impressed striae are also present in N. theresiae laterally on the propodeum and petiolar node, as well as longitudinal, and irregularly shaped on the posterior nodal face. The body dorsum, of N. bugabensis, on the other hand, is virtually striae-less. 3) The head of N. insignis is somewhat circular-shaped rather than subquadrate as in N. bugabensis. This latter trait is perhaps the easiest way to separate both forms.

Neoponera prasiosomis sp. nov. has the following differing features as compared to N. bugabensis: 1) The eye is large as compared to head length, it represents at least 29% of that measure, while in N. bugabensis the eye mostly represents 27% or slightly less. 2) The cuticle of N. prasiosomis is greenish (holotype from Panama) or brownish (paratype from Ecuador), while the cuticle of N. bugabensis is usually black, or rarely castaneous in one specimen from Coclé, Panama (CASENT0632922). 3) Appressed hairs in N. prasiosomis are pale yellowish and less abundant, especially on the gastral dorsum, than those in N. bugabensis which are bright golden and abundant, so that the gastral cuticle is not easily discernible. 4) Neoponera prasiosomis is smaller than N. bugabensis (Fig. 12).

Neoponera villosa is larger than N. bugabensis (Fig. 12) and has a tumulus on the posterior petiolar node face. This structure is absent in N. bugabensis.

Neoponera insignis variant N. villosa_cf2 (Fig. 26) differs in the following from N. bugabensis: 1) The petiolar node is higher than long in lateral view, while in N. bugabensis is approximately symmetric. 2) The head and mesosomal cuticle are violaceous-black (see previous comment above about the cuticle of N. bugabensis). 3) The gaster is covered by abundant, relatively opaque, yellow hairs, so that the cuticle is virtually invisible (Fig. 26). Gastral hairs of N. bugabensis are golden bright and the cuticle is slightly discernible. 4) This is a small form (TLa = 8 mm), clearly smaller than N. bugabensis (TLa: 8.5 – 10.3, Fig. 12).

Distribution notes. The elevational range of N. bugabensis spans from nearly the sea level, mostly in lowland rain forests, up to about 2300 m in mountainous Andean humid forests. Examined records belong from a number sites in Central America and northwestern South America. Mackay and Mackay (2010) report also a site near Puerto Maldonado, southeastern Peruvian Amazon. Neoponera bugabensis has been collected in various ecosystem types, from the Oaxacan montane humid forests near the Gulf of Mexico, to the Talamancan montane, Isthmian Atlantic and Pacific forests in Central America, to the Colombian and Ecuadorian Chocó-Darien, and the Napo moist forests (Amazonian) Ecuador.

Natural history notes. See Mackay and Mackay (2010) and Longino (2010). From the present material: this arboreal species has been collected mostly in mature, well-preserved forests, using several techniques like fogging, pitfall, arboreal pitfall, and directly by hand, either in daylight or at night, this latter though through insecticidal canopy knockdown.

Material examined. 22☿️, 3♀. COLOMBIA – Nariño: • 1☿️; Altaquér, Reserva Natural Río Ñambí; 1.3, -78.0833; alt. 1351m; 2010-04-08; Flores, E. leg.; hand collected; (MEPN). – Risaralda: • 6☿️; Puerto de Oro; 5.2995, -75.8869; alt. 1500m; 1991-09-01; Fernández, F. leg.; (ICN). – Valle del Cauca: • 1☿️; Guandal; 3.893, -77.069; alt. 6m; 1998-02-03; Riascos, Y. leg.; (ICN). • 1☿️; Km 18; 3.4, -76.5; (MUSENUV). • 1☿️; Vereda Campo Alegre, R. Bravo; 3.8167, -76.5167; alt. 1413m; 1984-02-05; Cepeda, O. leg.; (ICN). COSTA RICA – Heredia: • 1☿️; 16km SE La Virgen; 10.2682, -84.0842; alt. 500m; 2001-04-11; ALAS leg.; (JTLC). • 1☿️; La Selva Biological Station; 10.4333, -84.0167; alt. 50m; 1991-10-15; Longino, J. leg.; (INBC). – Limón: • 1☿️; Res. Biol. Hitoy Cerere; 9.6531, -83.0229; alt. 650m; 2015-06-11; Longino, J. leg.; (MUCR). ECUADOR – Esmeraldas: • 1♀; Reserva Ecológica Mache Chindul, Laguna de Cube; 0.3875, -79.65; alt. 434m; 2016/11; Troya, A. leg.; fogging; (MEPN). – Orellana: • 1♀; Parque Nacional Yasuní, Tiputini Biodiversity Station, 288 km SE Quito; -0.6319, -76.1442; alt. 230m; 2002-07-21; Erwin, T.; et al. leg.; fogging; (MEPN). • 2☿️; Parque Nacional Yasuní, Tiputini Biodiversity Station, 288 km SE Quito; -0.6167, -76.1333; alt. 240m; 2002-07-21; Erwin, T.; et al. leg.; fogging; (MEPN). – Pichincha: • 1☿️; Puerto Quito; -0.1, -79.2667; 1984/07; Ponce, P. leg.; (QCAZ). HONDURAS – Comayagua: • 1♀; PN Cerro Azul Meámbar; 14.8693, -87.8979; alt. 1170m; 2010-05-22; LLAMA leg.; (JTLC). • 1☿️; Parque Nacional Cerro Azul Meámbar; 14.8698, -87.8987; alt. 1120m; 2010-05-20; LLAMA leg.; (JTLC). MEXICO – Puebla: • 1☿️; 4km WNW Hueytamalco; 19.9567, -97.327; alt. 790m; 2019-06-15; Longino, J. leg.; (JTLC). NICARAGUA – Chontales: • 4km NE Cuapa; 12.2888, -85.3535; alt. 850m; 2011-04-20; Longino, J. leg.; hand collected; (JTLC). • 1☿️; 4km NE Cuapa; 12.2888, -85.3535; alt. 850m; 2011-04-20; Longino, J. leg.; hand collected; (JTLC). PANAMA – Chiriqui: • 1☿️; Bugaba; 8.4833, -82.6167; alt. 350m; Champion leg.; (MHNG). – Coclé: • 1☿️; 6 km NNW El Copé, Parque Nacional Omar Torrijos; 8.6669, -80.5887; alt. 790m; Longino, J. leg.; hand collected; (JTLC). – Panamá: • 1☿️; Cerro Azul, Los Altos; 9.22, -79.41; alt. 838m; 1994-05-24; Smith, N.; Kassabian, R. leg.; (UCDC).

Geographic range. Southern Mexico: Puebla, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Southern Peru*. *: Literature record.

Back_to_table_of_contents

4.2.2. Neoponera curvinodis (Forel 1899)

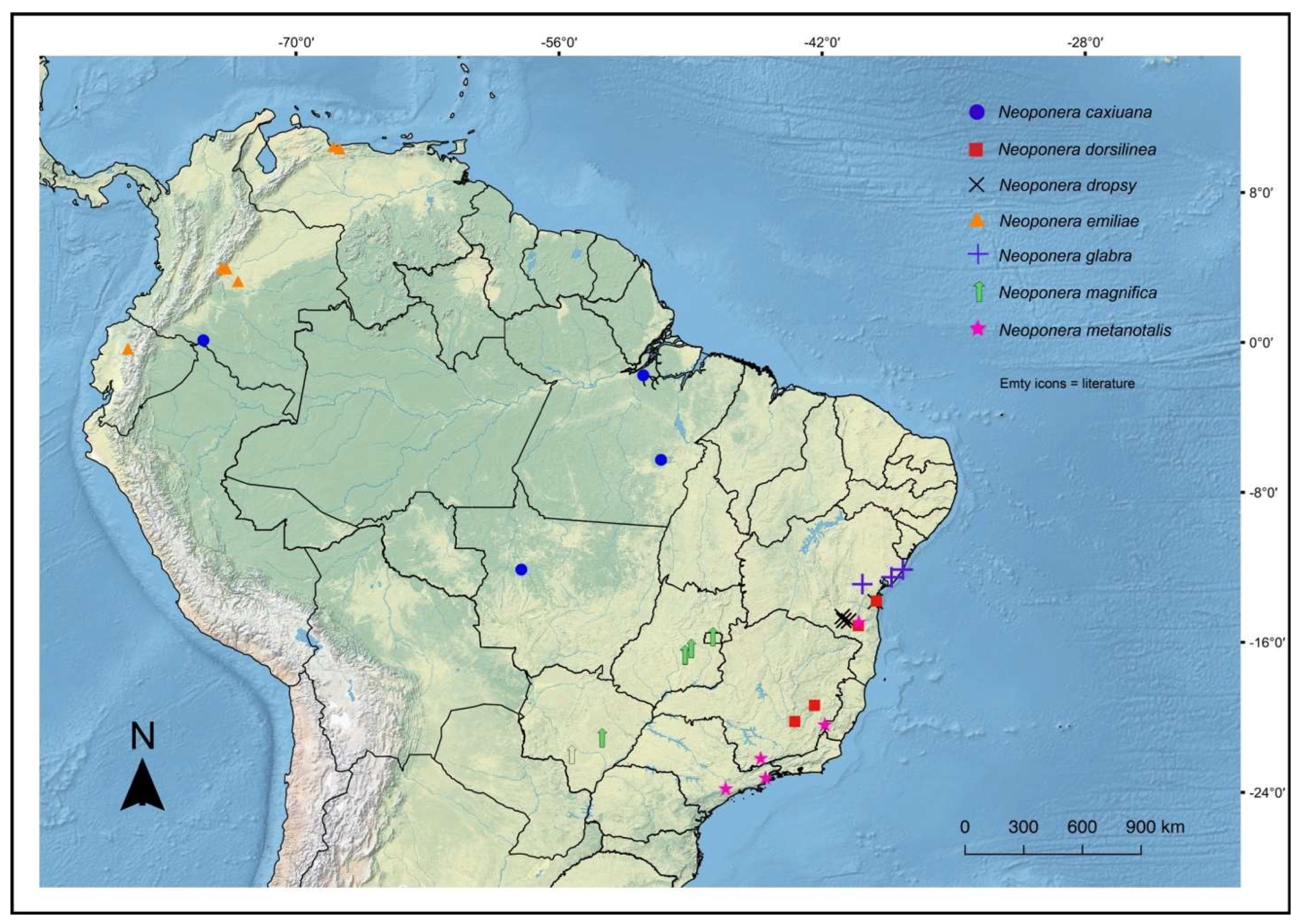

Figures. 7c (pronotum ☿); 8b, c (petiole ♀︎); 11a (propodeum♀︎); 18: a – e (☿); 30b (distribution).

Pachycondyla villosa curvinodis Forel, 1899:15. ☿ syntype, Guatemala, [Quetzaltenango province], Las Mercedes, Torola, Champion [leg.], MHNG [absent from collection]; ☿ syntype, Panama, [Chiriquí province] Bugaba, Volcan de Chiriqui, Champion, [leg.], (MHNG) [absent from collection].

Neoponera bactronica Fernandes et al. 2014: 136. Figs. 1 – 14, 106, 107 (☿, ♂). ☿ holotype, Brazil, Bahia, Ilhéus, CEPEC Genética, PI24 bis Phenotype 2, XI.1998, leg. D. Fresneau, (MZSP) [examined]; 5 ☿, 3 ♂ paratypes: ☿, same data as for the holotype, (INPA: INPA–HYM033260) [examined]; ☿, same data as for the holotype, except: #4905, 17.I.1995, leg. Arouca J., (NHMW) [not examined]; ♂, same data as for the holotype, except: CEPEC#4587, 15.X.1986, leg. P. Terra, (MZSP) [examined]; ♂, same data as for the holotype, except: CEPEC#4587, 23.II.1988, leg. P. Terra, (INPA: INPA–HYM033261) [examined]; ♂, same data as for the holotype, (CPDC) [not examined]; 2 ☿, same data as for the holotype, (CPDC) [not examined]; ☿, same data as for the holotype, except: CEPEC, 6.XI.2007, leg. A.F.R. Carmo & I. C. Nascimento, (MPEG) [not examined]. Syn. nov.

Neoponera billemma Fernandes et al. 2014: 140. Figs. 15 – 29 (☿, ♀︎). ☿ holotype, Brazil, Pará, Benevides, Morelândia, 16.VI.1988, leg. Bittencourt, (MZSP) [examined]; 1 ☿, 2 ♀︎ paratypes: ☿ Brazil, Goiás, 1980, leg. Kent Redford, #124, (INPA: INPA–HYM033262) [examined]; ♀︎, same data as preceding, (NHMW) [not examined]; ♀︎, Brail, São Paulo, Rio Claro, 22.VIII.2000, leg. D. Fresnau, (CPDC) [not examined]. Syn. nov.

Neoponera subversa Lucas et al. 2002: 256. Fig. 1c (☿). (nomen nudum, unavailable). Syn. nov.

☿ neotype [present designation], Guatemala, Patulul [information on label hand written by A. Forel] (MHNG: MHNGENTO00097877) [image examined]. Note: material from A. Forel collection at MHNG; misidentified by him as N. villosa].

Combinations. In Neoponera: Emery, 1901: 47; in Pachycondyla: MacKay & MacKay, 2010: 297

Subspecies of Neoponera villosa: Forel, 1901: 45.

Status as species. MacKay & MacKay, 2010: 297 [redescription].

Senior synonym of Neoponera inversa: Emery, 1911: 73

Worker and queen diagnosis. Head rectangular, longer than broad, lateral head margin moderately straight, posterior head margin concave (Fig. 18a); antennal scape, when pulled posterad, exceeding posterior head margin by two times apical scape width, usually slightly more (Fig. 18b); posterolateral propodeal margin with raised carina, feebly crenulate (Fig. 18a, 11a), posterior propodeal face usually slightly concave dorsally, just in between propodeal carinae; in lateral view, anterior margin of petiolar node straight, inclined posterad, distal portion usually slightly curved anterad (Fig. 8b, 18a); in lateral view, posterior nodal margin convex, meeting anterodorsally with anterior margin in acute angle, ca. 45° (Fig. 8b); anterolateral nodal face usually feebly deflate, this is better discernible on the distal nodal portion (Fig. 8b, 18d).

Worker. Measurements (n = 64): HW: 2.12-2.91; HL: 2.38-3.28; EL: 0.56-0.85; SL: 2.44-3.25; WL: 3.94-5.03; PrW: 1.56-2.19; MsW: 1.0-1.44; MsL: 0.75-1.22; PW: 1.12-1.56; PH: 1.25-1.72; PL: 1.08-1.62; GL: 3.69-6.0; A3L: 1.47-2.09; A4L: 1.56-2.16; A3W: 1.81-2.31; A4W: 1.94-2.5; TLa: 10.79-13.91; TLr: 11.5-15.31. Indices. CI: 75.56-118.42; OI: 23.92-32.35; SI: 97.78-129.41; MsI: 108.57-140.74; LPI: 83.7-113.08; DPI: 85.42-115.79.

Queen. Measurements (n = 16): HW: 2.62-3.12; HL: 2.94-3.44; EL: 0.72-0.91; SL: 2.56-3.25; WL: 4.75-5.56; PrW: 2.0-2.56; MsW: 1.81-2.06; MsL: 1.65-2.62; PW: 1.38-1.75; PH: 1.45-1.88; PL: 1.25-1.69; GL: 4.81-6.69; A3L: 2.0-2.38; A4L: 2.0-2.41; A3W: 2.31-2.69; A4W: 2.44-2.84; TLa: 13.31-15.38; TLr: 13.94-17.12. Indices. CI: 88.24-97.87; OI: 24.47-31.82; SI: 93.18-107.14; MsI: 76.54-112.12; LPI: 80.7-98.11; DPI: 83.02-120.0.

Male. Described by Fernandes et al. (2014). The following is added to their diagnosis: notauli not touching posteriorly; shallow to absent anteromedian dorsal groove on propodeum, showing horizontal rugae; propodeum posterolaterally with blunt carina which does not reach dorsum; in lateral view, anterior margin of petiolar node mostly straight (it does not show the typical distally curved projection of workers and queens); lateral nodal margin feebly angulate, but this is hardly discernible since it bears abundant, slightly raised piligerous punctae; abundant yellow subappressed pilosity, most of which is arranged in groups of stacked hairs, like if they were combed; abdominal sternum VII flat to feebly concave, bearing appressed hairs though not abundant.

Figure 18.

Neoponera curvinodis neotype. ☿ (MHNG: MHNGENTO00097877), Guatemala. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view; d. Petiole in anterolateral view; e. Collection labels. Note: A. Forel misidentified this specimen as N. villosa. Images by Bernard Landry, MHNG.

Figure 18.

Neoponera curvinodis neotype. ☿ (MHNG: MHNGENTO00097877), Guatemala. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view; d. Petiole in anterolateral view; e. Collection labels. Note: A. Forel misidentified this specimen as N. villosa. Images by Bernard Landry, MHNG.

Male. Measurements (n = 4): HW: 1.38-1.72; HL: 1.44-1.69; EL: 0.84-0.89; SL: 0.31-0.38; WL: 4.06-4.5; PrW: 1.62-1.75; MsW: 1.84-2.09; MsL: 2.31-2.5; PW: 0.78-0.88; PH: 0.94-1.09; PL: 1.06-1.19; GL: 5.0-5.62; A3L: 1.44-1.72; A4L: 1.56-1.81; A3W: 1.31-1.59; A4W: 1.81-2.0; TLa: 9.69-10.78; TLr: 12.0-12.88. Indices. CI: 92.59-105.77; OI: 50.91-61.36; SI: 20.0-22.73; MsI: 74.68-90.54; LPI: 103.03-120.0; DPI: 69.44-82.35.

Comments. Neoponera curvinodis is the largest species in the N. foetida group (Fig. 12; ☿ TLa = 10.8 – 13.9 mm; ♀︎TLa = 13.3 – 15.4 mm), and is the second largest in the genus after N. commutata Roger. Size variation in the worker caste is relatively large (SD = 0.69), and it is assumed something similar occurs in the queen, but few specimens were gathered and measured so as to reach a more solid conclusion.

Neoponera zuparkoi, N. villosa, and in particular N. inversa are morphologically most similar to N. curvinodis (see comparison further below). Their distinction can be daunting if diagnostic features are not carefully examined. Plasticity is prevalent in both N. curvinodis and N. inversa. Some variations like the shape and orientation of the mid clypeal striae, or the shape of the humeral carina and of the petiolar node can certainly obscure their taxonomic distinction. For example, the humeral carina can be well-developed and salient (Fig. 7c, 18c), or just feebly emerging from the cuticle.

The following three body regions are considered plastic in both workers and queens in Neoponera curvinodis, none of these variations are geographically correlated: the head lateral margin, the carina at the propodeal posterolateral margin, and the anterior margin of the petiolar node. The first two are less variable than the third. As for the lateral head margin, a moderately straight form (Fig. 18b) is dominant over a somewhat curved form (link). Both variations are usually imperceptible and can be detected only when examining numerous specimens representing a broad geographic range. The propodeal carina, on the other hand, is easier to distinguish, it may be clearly raised with weak crenulae (Fig. 11a, 18a), which is the most common form, or it may be just slightly raised with almost no signs of crenulae (Fig. 11b). The distal region of the anterior nodal margin may be curved anterad (Fig. 8b), or the margin is just slightly concave to straight distally (Fig. 8c). When the first state is present, the anterolateral nodal face is usually deflate. Both forms, concave or straight nodal margin, can be present in specimens obtained from the same collection events, and even from the same nest series (Fig. 8b, c). The degree to which the cuticle of the petiolar node is deflate or contracted is perhaps the clearest example of plasticity in this species, but also in N. inversa. We hypothesize this could be the result of a physiological condition since it is present even among nestmates. We assume it could be due to variations in individual development, maybe linked to factors like diet (Thompson 1999, West-Eberhard 2005). If this hypothesis is further tested and potentially supported, then the question would be ¿Why it is present only in these lineages, i.e., N. curvinodis and N. inversa, and not in, for example, N. villosa and N. zuparkoi which are closely related to them? If this is not supported, and physiology does not play a role here, another potential explanation would come from evolution itself, by considering instead these changes in morphology, especially on the node, an adaptive response over (unknown) selection pressures of the environment. However, since both species occur in sympatry, especially in several South American regions (Fig. 30b), interspecific gene flow may also play a part here. If this is the case, then populational analyses, using for example maternally-inherited genetic material, would be useful for identifying first-generation hybrids, also called F1. A recent study by Weyna et al. (2022), showed that ultraconserved elements can also be used to unveil hybridization history in non-model organisms. They also found that amongst a number of tested organisms, ants showed the highest number of F1 hybrids, which suggests higher rates of recent hybridization.

Whatever the causes involved for explaining this phenomenon in both species, such phenotypic plasticity likely was the source of confusion while identifying N. curvinodis from its very similar congeners, in particular with N. inversa. The following features of workers and queens of N. curvinodis, in combination with the taxonomic key, make easier their distinction: 1) The lateral head margin is moderately straight, so that the head outline is typically rectangular-shaped (slightly convex in N. inversa); 2) The posterolateral propodeal margin usually has a crenulate, raised carina (absent or weakly developed in N. inversa); 3) The petiolar node is relatively broad in lateral view: ☿ PL = 1.1 – 1.63 mm, with the dorsoposterior margin meeting with the anterior margin in 45° angle. In N. inversa the node is narrower: ☿ PL = 1 – 1.25 mm, with its dorsoposterior margin usually meeting with the anterior margin in 30° – 35° angle; 4) The anterolateral distal nodal face is deflate (frequently), or not deflate at all (rarely), while in N. inversa is always deflate, so that the nodal top seems more curved anterodorsad than in N. curvinodis; 5) Neoponera curvinodis is bigger (☿ TLa = 10.8 – 13.9 mm) than N. inversa (☿ TLa = 10.2 – 12.2 mm). Notes: 1. While identifying these two taxa it is recommended making a final decision based on these five characters together; 2. Although the range cited for the variables Petiolar Length (PL) and Total Length accurate (TLa) was obtained from a number of specimens and localities in the Neotropics, the reader may expect these limits to fall out of such ranges.

Both N. curvinodis and N. inversa are distinguishable from N. villosa by examining the shape of the petiolar node: In N. villosa the anterior margin is vertically straight or nearly so, and the convex dorsoposterior face has a tumulus, better discernible in lateral view (Fig. 2b). This tumulus is absent in N. curvinodis and N. inversa. Also, the anterior half of the nodal dorsal margin is almost horizontally straight in N. villosa, it meets in ca. 90° angle with its anterior margin, and the nodal top is convex, in lateral view. In N. curvinodis and N. inversa the nodal dorsal margin is always inclined posterad, and the nodal top is relatively acute.

Neoponera curvinodis is also very similar to N. zuparkoi, but the nodal shape of this latter is not deflate anteriorly, and has a tumulus on the posterodorsal face. The nodal shape of N. zuparkoi is almost identical to that of N. villosa (see prior paragraph). In addition, the humeral carina of N. zuparkoi is not salient, while in N. curvinodis is either strongly or feebly salient. The anterior mesopleural margin of N. zuparkoi has a protruding, anteroventrally directed cuticular lobe (Figs. 7a-b). Such region in N. curvinodis is only carinate as in all other members of the N. foetida group.

Justification for the neotype designation. The primary type material, which should be located in MHNG in Geneve, is absent from collection (Bernard Landry, pers. comm.). Since the worker syntype was collected by Mr. Champion, the other possible repositories for this specimen are the BMNH in London, or the USNM in Washington D.C. Information on this subject was requested to the BMNH and their online collections database was searched. The USNM ant collection was also examined. The type material is not vouchered in those institutions. Brian Fisher’s imaging team could not locate this type in other relevant insect collections either. Designation of a neotype is necessary since this form is barely distinguishable from its highly similar congener, N. inversa, but also from N. zuparkoi and N. villosa, although with relatively less degree of difficulty. The chosen neotype is a worker from Patulul in Guatemala, a site approximately 230 Km west Las Mercedes, the type locality of this species. This specimen was misidentified by Auguste Forel as N. villosa (hand written on original label, Fig. 18e), and its morphology matches that of other specimens collected in Costa Rica, which are part of his collection preserved in MHNG, and identified by him as N. villosa var. curvinodis. The newly designated neotype is well-preserved and potentially suitable for molecular analyses.

Neoponera bactronica and N. billemma as junior synonyms of N. curvinodis. Two sources of evidence support these synonymies:

1) The morphology of the examined type material of N. bactronica and N. billemma match the form of the presently designated neotype of N. curvinodis. The above shown variable body regions detected in N. curvinodis are also present in examined populations of the synonymized forms. Furthermore, the NMDS analysis based on 24 morphometric variables shows that specimens previously identified as N. bactronica, N. billemma, and N. curvinodis share almost all of their morphospace represented in the first two dimensions of the ordination with a strong stress value of 0.0893, thus indicating the observations are not randomly grouped (Fig. 19). These results are statistically supported by the pairwise contrast test which suggests these three forms are not different (p adjusted = 1). The global PERMANOVA analysis, on the other hand, rejected the null hypothesis that all observations are equal (p < 0.000999, 33% variance explained). This result is coherent with the taxa that share only some of their morphospace, this is, N. inversa and N. villosa, and does not apply to the other three forms which are grouped under the morphospace of a single species, here considered N. curvinodis.

Figure 19.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) representing the distribution of specimens (icons) in the morphospace of some closely related species of the N. foetida group, two of which are here considered junior synonyms of N. curvinodis. Abbreviated letters represent the 24 morphometric variables involved in the analysis. The closer these are to the observations, the more relevant they are for explaining the observed ordination. Dashed circles represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 19.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) representing the distribution of specimens (icons) in the morphospace of some closely related species of the N. foetida group, two of which are here considered junior synonyms of N. curvinodis. Abbreviated letters represent the 24 morphometric variables involved in the analysis. The closer these are to the observations, the more relevant they are for explaining the observed ordination. Dashed circles represent the 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, the diagnostic characters of both N. bactronica and N. billemma do not support their specific status. As for N. bactronica, the first two characters, namely “head strongly punctate on frontal face; notopropodeal groove strongly marked on dorsum” (Fernandes et al. 2014, pg. 136) are also present in all lineages of the N. foetida group. The dorsal punctae on the head are usually shown in combination with striae of differing depth degree. In Neoponera this trait is highly homoplastic, thus not useful for species diagnoses in most cases, except for few species in the N. aenescens group, like N. carbonaria (Smith) where the head dorsum is typically micropunctate. The second trait, the notopropodeal groove, shows little interspecific variation and is considered apomorphic in the N. foetida group. This trait is absent in almost all species of the N. crenata group, its siter clade, and is regained in the remaining Neoponera groups (Troya et al. unpublished). The third character “petiole without striae and longer than high in lateral view” (Fernandes et al. 2014, p. 136) is partially informative because the ratio of the nodal length vs its height is not intraspecifically constant. Also, most workers identified as N. bactronica have the node slightly higher than long as seen laterally, not longer than high as reported in Fernandes et al. (2014). Similar morphometric measurements were obtained in N. curvinodis and N. inversa. In N. villosa, the opposite pattern is found where the node is slightly longer than high, or rather symmetric. As for N. billemma, a pattern is impossible to discern since only two workers are known. However, the node of the paratype is also higher than long.

Current nodal morphometrics of N. curvinodis, N. inversa, and N. villosa match those of Lucas et al. (2002) for their morphospecies “Pvi2”, “Pvi1”, and “Pvv”, respectively. Lucas et al. (2002) believed Pvi2 belonged to a new species and provisionally called it “Pachycondyla subversa” (currently nomen nudum). Based on Forel’s (1899) illustration of N. curvinodis, specifically on the measurement of the petiolar node (height and length) and on the shape of the anterior margin, i.e., concave, Mackay and Mackay (2010) inferred that Pvi2 closely matches N. curvinodis. This is also supported here since the nodal shape of Pvi2 (Fig. 1c in Lucas et al. 2002) matches that of the neotype of N. curvinodis.

Therefore, if Pvi2 represents N. curvinodis (and not a new, but distinct species from N. inversa according to Mackay and Mackay 2010), then further erection of a new lineage (i.e., N. bactronica) was not required. Since N. curvinodis and N. inversa are so similar, commonly collected, and occur in sympatry in most regions for which we gathered specimens, it is crucial to first examine as much material as possible from their entire range. Examination of the type material is also very important, but also revising historical specimens identified by Forel.

Neoponera billemma, on the other hand, is diagnosed as a species with “Strong transverse striae on the [mid] clypeus; anterior face of petiole lightly striate below and concave” (Fernandes et al. 2014, p. 141). The first trait, the mid clypeal striae, is another plastic feature in Neoponera. Among the material thus far examined for the genus, these striae can vary intraspecifically with no detected geographical pattern. Although these striae are usually longitudinal in Neoponera, sometimes these are also: horizontal e.g., JTLC: INBIOCRI001281564 from Costa Rica (N. insignis); oblique, e.g., CPDC: AT570 from Bahia, Brazil (N. villosa); fingerprint-like, e.g., CPDC: AT922 from Distrito Federal, Brazil (N. curvinodis); mixed: horizontal and longitudinal, e.g., JTLC: CASENT0617097 from Honduras (N. bugabensis); or simply smooth, without striae, e.g., JTLC: JTL7597-S from Nicaragua (N. villosa). Out of the N. foetida group, the horizontally impressed striae also occur in for example, the N. crenata group: MZSP: MZSP123017 from Santa Catarina, Brazil (undescribed species). As for the second trait, “petiolar node lightly striate below”, cited as diagnostic for N. billemma in Fernandes et al. (2014), many specimens from all species in the N. foetida group show these striae in variable depth degree. Finally, the nodal anterolateral concavity is another plastic feature of N. curvinodis, as previously commented.

2) Phylogenetic evidence. The phylogeny of the genus based on ultraconserved elements recovered with high support (100 % bootstrap) N. curvinodis, N. inversa, and N. villosa as distinct but closely related lineages (Troya et al., unpublished). Neoponera zuparkoi and the morphospecies N. ecu2923 (see details further below under that species), emerge as sister to N. inversa, with low support, though. Santos et al. (2018) tested the specific status of the first three species and also included N. bactronica. Based on specimens from two regions of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest they sequenced two mitochondrial genes (CO1, 16S) and studied their karyotypes. They concluded these represent four distinct lineages. We agree with them except for N. bactronica which is grouped with N. curvinodis in the same clade (see their Fig. 2). Nonetheless, they suggested that N. bactronica and N. curvinodis diverged recently, and proposed further research on this issue. Mendoza-Ramírez et al. (2019) sequenced two mitochondrial genes (CO1, Cyt b) and eight nuclear microsatelites of the above species plus N. solisi and N. bugabensis. In their phylogeny N. curvinodis is sister to N. bactronica + N. villosa (Fig. 2 in their work). Neoponera bactronica, however, was represented by specimens from only two regions: a site in Mato Grosso (Brazil), and another from Colombia. Neoponera curvinodis was better represented by four specimens from: Chiapas (Mexico), Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and two from the same site in Mato Grosso. The authors showed that both N. bactronica and N. curvinodis have considerably high intraspecific genetic distances, up to 5.1% and 9.5 % for the CO1 and Cyt b, respectively, which is depicted in, for example, the long branch separating the Brazilian specimens from those of Colombia. They brought out two potential causes for this result: 1) A marked mitochondrial genetic structure which has been observed in other broadly ranged lineages, like Solenopsis saevissima (Smith), or 2) Each form could represent more than one species. Similarly, in the Neoponera phylogeny one N. curvinodis specimen (INPAHYM033801-2) from Santa Catarina, southern Brazil showed a significantly larger branch than its conspecific (DZUP549372) from Sergipe, northeast Brazil. The observed plasticity of this species probably mirrors its high intraspecific genetic distance, in particular between geographically divergent populations.

In this revision we cannot confirm nor deny a multispecies hypothesis to further understand the systematics of N. curvinodis. Yet, the present data set does not seem to favor a cryptic status since this taxon is now re-diagnosed, although showing some level of intraspecific variation among the proposed characters. This new diagnosis fits well in the phylogeny of Neoponera (Troya et al., unpublished) allowing distinction from its putatively closest species, N. inversa, N. villosa, and N. zuparkoi.

Natural history and distribution notes. See Mackay and Mackay (2010), and Fernandes et al. (2014). From the presently examined material: Neoponera curvinodis has been collected during daylight, in a variety of habitats from primary well-preserved, to second-growth, to relatively disturbed forests, using mostly canopy-aimed techniques like fogging, pitfall and arboreal Malaise, and less intensely through CDC, and mercury light trapping, Malaise, beating, sweeping, pan-trapping, Winkler, and hand collecting. Specimens and/or colonies have been found in Cinnamomum chavarrianum (Lauraceae), Miconia cinerascens, Clidemia hirta (Melastomataceae), Qualea grandiflora (Vochysiaceae), Theobroma cacao (Malvaceae) in agriculture systems, as well as in palms (e.g., Bactris spp.) and bromeliads. The elevational record extends from nearly the sea level up to 2300 m, this latter obtained in Cordillera del Cóndor, Ecuador. Neoponera curvinodis has been abundantly collected in the Atlantic Forest, and a number of records belong also from most Brazilian biomes except for the Pampa. Outside Brazil, records span from Amazonia, to the Venezuelan Cordillera de la Costa and Formación Lara-Falcón, to the Chocó-Darién and the Pacific and Atlantic lowland forests in Central America.

Material examined. 218☿️, 22♀, 15♂. BRAZIL – Acre: • 1☿️; Senador Guiomard; -10.0667, -67.6167; alt. 214m; 2014-05-31; Denicol, M. R.; Santos, A. M. leg.; arboreal pitfall; (DZUP). – Amapá: • 1♀; [no locality given]; 1.0, -52.0; 1978-10-22; Torres, M. leg.; (MPEG). • 1☿️; [no locality given]; 1.0, -52.0; 1978-10-21; Torres, M. leg.; (CPDC). – Amazonas: • 1☿️; Br. 174, Km 44; -2.724, -60.0472; alt. 72m; 1994-11-17; Harada, A. leg.; (INPA). • 1☿️; Carabinaui river; -2.5307, -62.1502; alt. 146m; 1995-04-28; Motta; et al. leg.; light trap; (INPA). • 1♂; Liberdade river, Estirão da preta; -7.35, -71.8167; alt. 175m; 2011-05-11; Rafael, J.; et al. leg.; hand collected; (INPA). • 1☿️; Manaus; -3.1167, -60.0167; alt. 65m; 1989-02-26; Vogh, R. leg.; (INPA). • 1♀; Reserva Florestal Adolpho Ducke, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA); -2.9167, -59.9833; alt. 65m; 2010-05-16; Belmont, E. leg.; (INPA). – Bahia: • 2☿️; 1.5 km E of Guaratinga; -16.5833, -39.7667; alt. 151m; 2002-12-06; Santos, J. R. M. leg.; baiting; (CPDC). • 1☿️; 16 km N of Vitoria da Conquista; -15.0333, -49.9; alt. 752m; 2003-07-14; Carmo, J. C. S. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; 20 km E of Anadaraí; -12.7508, -41.1669; alt. 323m; 2001-03-16; Santos, J. R. M. leg.; (CPDC). • 1♂; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.75, -39.2167; alt. 61m; 1986-10-15; Terra, P. leg.; (MZSP). • 1♂; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.75, -39.2167; alt. 61m; 1988-02-23; Terra, P. leg.; (INPA). • 1♀; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.7659, -39.2159; alt. 53m; 1999-01-28; Delabie, J. H. C. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.75, -39.2167; alt. 61m; 1998-11-01; Fresneau, D. leg.; (MZSP). • 3☿️; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.75, -39.2167; alt. 61m; (CPDC). • 1☿️; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.7659, -39.2159; alt. 53m; 2017-08-01; Carvalho, E.; Queiroz, J. leg.; Malaise; (CPDC). • 1☿️; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.7659, -39.2159; alt. 53m; 2012-05-17; Silva, J. A. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; 3.3 Km N main entrance CEPLAC-CEPEC, Ilhéus-Itabuna road; -14.75, -39.2167; alt. 61m; 1998-11-01; Fresnau, D. leg.; (INPA). • 1☿️; Andaraí; -12.8, -41.33; alt. 400m; 1993-01-01; Almeida, C. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Andaraí; -12.758, -41.177; alt. 340m; 2001-03-16; Santos, J. R. M. leg.; (CPDC). • 1♂; Fazenda Bom Jesus; -7.1397, -45.3467; alt. 214m; 1992-04-11; Cardoso, P. leg.; (INPA). • 3☿️; Fazenda Bom Jesus; -7.1397, -45.3467; alt. 214m; 1992-02-10; Cardoso, P. leg.; (CPDC). • 2☿️; Fazenda Bom Jesus; -7.1397, -45.3467; alt. 214m; 1992-04-11; Cardoso, P. leg.; (INPA). • 3☿️; Fazenda Silêncio ; -13.8585, -40.0838; alt. 214m; 1997-12-02; Argolo, J. S. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Ilhéus; -14.7972, -39.035; alt. 23m; 1988-09-27; Diniz leg.; hand collected; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Indaiá; -14.52, -40.37; alt. 790m; 1988-02-04; Santos, J. R. M. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Itabuna; -14.79, -39.28; alt. 60m; 2002-09-01; Santos, J. R. M. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Itapebi; -15.9687, -39.5321; alt. 195m; 1980-04-11; Forbes; Benton leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Porto Seguro; -16.4455, -39.0658; alt. 3m; 1998-11-07; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Porções; -14.52, -40.36; alt. 770m; 2004-01-25; Mariano, E. leg.; (CPDC). • 1♂; Reserva Biológica do Una; -15.1768, -39.1053; alt. 108m; 2011-11-01; Sena, D. U. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; São Domingos, Praia do Norte ; -14.7466, -39.0627; alt. 5m; 1995-05-07; Delabie, J. H. C. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; São José, Chapada Diamantina; -11.4408, -39.8778; alt. 392m; 2001-03-22; Santos, J. R. M. leg.; Winkler; (CPDC). – Distrito Federal: • 1☿️; APA Gama Cabeça de Veado; -15.8667, -47.8333; alt. 1080m; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Area de Proteção Ambiental Gama Cabeça de Veado; -15.8667, -47.8333; alt. 1080m; 2000-03-02; Mirelle, P. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Area de Proteção Ambiental Gama Cabeça de Veado; -15.8667, -47.8333; alt. 1080m; 2000-02-01; Mirelle, P. leg.; (CPDC). • 2♀; Brasilia; -15.8261, -47.9207; alt. 1080m; 1976-07-06; Diniz, J. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Brasilia; -15.8261, -47.9207; alt. 1080m; 1976-07-06; Diniz, J. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Fazenda Agua Limpa; -15.9488, -47.9342; alt. 1085m; 2007-05-24; Maravalhas, J. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Parque Nacional de Brasilia; -15.7293, -47.9613; alt. 1120m; 2014-01-18; Sendoya, S. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; RECOR IBGE; -15.9163, -47.8672; alt. 1161m; 2017-11-01; Lasmar, C. leg.; pitfall; (DZUP). – Goiás: • 1☿️; 17 km NE of Jataí, Fazenda Rio Paraíso; -17.7333, -51.6167; alt. 891m; 2011-01-28; Diniz, J. leg.; pan trap; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Açude; -17.8587, -51.727; alt. 788m; 2005-08-20; Paniago, G. leg.; (DZUP). • 1♀; Fazenda Luziana; -17.8715, -51.7309; alt. 831m; 2002-05-08; Diniz.; et al. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Fazenda Santa Lucia; -17.0635, -51.6155; alt. 537m; 2008-10-10; Diniz, J. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Goiás; -15.8257, -49.836; 1970-01-01.000001980; Redford, K. leg.; (INPA). • 1☿️; Parque Nacional Chapada dos Veadeiros; -14.0388, -47.623; alt. 1287m; 2003-02-01; Ribas, C.; Madureira, M. leg.; arboreal pitfall; (DZUP). • 1♀; Parque Natural Municipal Mata Do Açude; -17.8605, -51.728; alt. 791m; 2005-11-12; Diniz, J. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Parque Natural Municipal Mata Do Açude; -17.8605, -51.728; alt. 791m; 2005-12-21; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Pequena Central Hidrelétrica (PCH) de Fazenda velha; -17.9706, -51.7627; alt. 623m; 2009-03-18; pan trap; (DZUP). – Mato Grosso: • 1☿️; Chapada dos Guimarães; -15.45, -55.7333; alt. 726m; 1983-11-27; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Chapada dos Guimarães; -15.45, -55.7333; alt. 726m; 1983-07-08; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Chapada dos Guimarães; -15.3, -55.9333; alt. 257m; 1983-12-04; (DZUP). • 1♀; Colégio Agricultura Buriti, Chapada dos Guimarães; -15.45, -55.7333; alt. 726m; 1982-11-12; Zanuto, M. leg.; (MPEG). • 1☿️; Sesc. Pantanal; -16.5083, -56.4161; alt. 135m; 2017-04-01; Lasmar, C. leg.; pitfall; (DZUP). – Mato Grosso do Sul: • 1♀; 28 km E of Bataiporã; -22.35, -52.9333; alt. 294m; 2012-12-03; Savaris, M.; Lampert, S. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Dourados Rodovia Itahum Km 2; -22.221, -54.8055; alt. 445m; 2019-07-14; Santos,P.; et al. leg.; (DZUP). – Minas Gerais: • 1☿️; Boa Esperança; -21.0667, -45.6; alt. 845m; 2014-03-19; Queiroz; et al. leg.; pitfall; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Chapada dos Guimarães; -15.3, -55.9333; alt. 308m; 1983-07-04; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Fazenda Recife; -16.0167, -41.2667; 1989-07-21; Paiva, R. leg.; (MZSP). • 1☿️; Itumirim; -21.2333, -44.8167; alt. 925m; 2014-02-19; Queiroz; et al. leg.; arboreal pitfall; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Itumirim; -21.2167, -44.8333; alt. 925m; 2014-02-19; Queiroz; et al. leg.; arboreal pitfall; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Itumirim; -21.2167, -44.8333; alt. 885m; 2014-02-19; Queiroz; et al. leg.; arboreal pitfall; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Parque Estadual do Rio Preto; -18.1167, -43.3333; alt. 845m; 2017-11-01; Reis, A.; et al. leg.; pitfall; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Pq. Floresta do Río Doce; -19.7, -42.7333; alt. 580m; 1989-09-23; Mel, G. A. R. leg.; (DZUP). • 1♀; UFU, Campus Santa Mônica; -19.5167, -52.2667; alt. 870m; 2013-12-23; Bueno, B. leg.; (DZUP). – Paraná: • 1☿️; 7 km NW of Paranavaí, BR376 km 96; -23.0167, -52.5; alt. 486m; 2019-02-20; Azevedo, F.; Freitas, D. S. leg.; pitfall; (DZUP). • 1♀; Antonina; -25.3, -48.7667; alt. 114m; 2014-03-02; Calixto, J.; Feitosa, R. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Antonina; -25.3, -48.6833; alt. 25m; 2009-09-14; Donatti, A. J.; Souza, J. M. T. leg.; (DZUP). • 1♀; Antonina centro; -25.4307, -48.7127; alt. 40m; 1966-01-19; Azevedo, M. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Entorno do rio Brumado; -25.3402, -48.885; alt. 397m; 2017-10-18; Pinto, A.; et al. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Foz do Iguaçu; -25.5, -54.5833; alt. 206m; 2000-08-20; Delabie, J. leg.; hand collected; (CPDC). • 1♀; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1984-12-06; Malaise; (DZUP). • 3☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-12-27; Malaise; (DZUP). • 2☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-05-13; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1984-12-10; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1984-12-03; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-05-17; light trap; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-01-21; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-02-04; Malaise; (DZUP). • 2☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-01-06; Malaise; (DZUP). • 2☿️; Instituto Agronômico do Paraná; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-01-28; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Morretes; -25.4, -49.25; alt. 963m; 1985-02-25; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Ourizona; -23.4167, -52.2; alt. 457m; 2005-07-23; Barbosa, A. C. leg.; (DZUP). • 5☿️; Parque Nacional Iguaçu, 19 Km SE Foz do Iguaçu; -25.65, -54.4333; alt. 225m; 2017-10-01; Troya, A. leg.; hand collected; (MEPN). • 1☿️; Reserva Guaricica, Sede SPVS; -25.3136, -48.6956; alt. 6m; 2019-03-23; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Reserva Natural Guaricica; -25.3, -48.6833; alt. 25m; 2010-01-14; Donatti, A. J.; Souza, J. M. T. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Reserva Natural Guaricica; -25.3, -48.6833; alt. 25m; 2009-12-09; Donatti, A. J.; Souza, J. M. T. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Reserva Natural Guaricica; -25.3, -48.6833; alt. 25m; 2010-12-12; Souza, J. M. T. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Reserva Natural Guaricica; -25.3, -48.6667; alt. 110m; (DZUP). – Pará: • 1☿️; Benevides ; -1.35, -48.25; alt. 31m; 1988-06-16; Bittencourt, N. leg.; (MZSP). • 1☿️; Fazenda Florentino; -7.1167, -55.3833; alt. 967m; 2010-12-12; Krinsk, D. leg.; pitfall; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Floresta Nacional Caxiuanã; -1.7333, -51.45; alt. 21m; 2016-09-29; Silva, R.; et al. leg.; pitfall; (MPEG). – Pernambuco: • 1☿️; Tapera; -9.3898, -40.5146; alt. 381m; 1929-01-26; Pickel, B. leg.; (INPA). – Rio de Janeiro: • 2☿️; Ilha Grande; -23.1518, -44.2289; alt. 991m; 2013-11-18; Leponce, M.; Queiroz, J. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; [locality not given]; -22.9477, -43.212; alt. 280m; 1927-12-22; Conde, O. leg.; (INPA). – Rondônia: • 1♀; Ji-Paraná; -10.88, -61.95; 1984-07-15; Overal, W. leg.; hand collected; (MPEG). • 1☿️; Reserva do INPA; -10.7, -62.2; 1985-03-29; Ramos, F. leg.; hand collected; (MPEG). – Roraima: • 1☿️; Parque Nacional Serra da Mocidade; 1.6, -61.9; alt. 600m; 2016-01-15; Xivier, F.; et al. leg.; (INPA). – Santa Catarina: • 1♀; Unidade de Conservação Ambiental Desterro-UCAD; -27.5167, -48.5; alt. 241m; (CPDC). • 1♀; Unidade de Conservação Ambiental Desterro-UCAD; -27.5167, -48.5; alt. 241m; 2005-08-19; Zillikens, A. leg.; (INPA). • 1☿️; Unidade de Conservação Ambiental Desterro-UCAD; -27.5833, -48.5333; alt. 22m; 2005-08-19; Schmid, V. leg.; (DZUP). • 3☿️; Unidade de Conservação Ambiental Desterro-UCAD; -27.5167, -48.5; alt. 241m; 2005-08-19; Zillikens, A. leg.; (INPA). – Sergipe: • 1☿️; Santa Luzia do Itanhi; -11.4167, -37.4167; alt. 6m; 1993-10-05; Delabie, J. leg.; hand collected; (CPDC). • 1☿️; São Cristovão; -10.9, -37.1833; alt. 21m; 1995-01-01; Feneron , R. leg.; (CPDC). • 1♀; UFS; -10.9167, -37.1; alt. 7m; 2015-06-16; Cruz, N. G. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Campus São Cristóvão; -10.9264, -37.1026; alt. 9m; Feneron, R. leg.; (CPDC). – São Paulo: • 1♀; 33 km SW of José Bonifácio, Rio Tietê; -21.2199, -49.9575; alt. 359m; 1979-09-02; Diniz, J. leg.; (DZUP). • 3☿️; Eng. Schmitt; -20.8669, -49.31; alt. 517m; 1970-11-16; Diniz, J. L. M.; Caballero leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Estação Ecologica de Itirapina; -22.2144, -47.9234; alt. 770m; 2014-03-06; Sendoya, S. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Fazenda Campininha; -22.2167, -47.1167; alt. 722m; 1977-05-27; (DZUP). • 2☿️; Ilha dos pescadores (Ilha da Vitória); -23.75, -45.0; alt. 33m; 1964-03-24; D. Zoologia leg.; (MZSP). • 2☿️; Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas (Ibilce), UNESP; -20.7852, -49.3598; alt. 533m; 1996-10-25; Izzo, T. J. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Iporanga; -24.5859, -48.5945; alt. 96m; 1961-11-01; Lenko, K.; Reichardt leg.; (INPA). • 6♂; Mata de Santa Genebra; -22.8228, -47.1094; alt. 631m; 2009-11-01; Fernandes, I. leg.; (INPA). • 1♀; Mata de Santa Genebra; -22.8228, -47.1094; alt. 631m; 2009-11-01; Fernandes, I. leg.; (INPA). • 61☿️; Mata de Santa Genebra; -22.8228, -47.1094; alt. 631m; 2009-11-01; Fernandes, I. leg.; (INPA). • 1☿️; Pratânia; -22.7667, -48.7333; alt. 657m; 2015-02-01; Veiga, P. A. S. leg.; (DZUP). • 1♂; Ribeirão preto, Campos da USP; -21.166, -47.8499; alt. 605m; 2019-03-02; Glaser, S. leg.; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Sete Barras; -24.3667, -47.9167; alt. 14m; 2004-07-11; Melo, G. leg.; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Sete Barras; -24.3667, -47.9167; alt. 14m; 2005-03-24; Melo, G. leg.; Malaise; (DZUP). • 2☿️; Sete Barras; -24.3667, -47.9167; alt. 14m; 2005-01-08; Melo, G. leg.; Malaise; (DZUP). • 1☿️; Severínia; -20.8062, -48.8092; alt. 579m; 1995-09-12; Fowler, H. G. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Sitio Caranda; -22.0861, -48.1274; alt. 663m; 2016-12-01; Oliveira, J. leg.; CDC; (MPEG). • 1♂; UNESP - Campus; -22.397, -47.5478; alt. 628m; 1999-11-01; Fresneau, D. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; UNESP - Campus; -22.397, -47.5478; alt. 628m; 1999-11-01; Fresneau, D. leg.; (CPDC). COLOMBIA – Chocó: • 3☿️; Estación Silvicultura al Bajo Atrato; 7.0406, -77.3378; alt. 149m; 1992-07-01; Mendoza, L. leg.; (MEPN). • 1☿️; Estación Silvicultura al Bajo Atrato; 7.0406, -77.3378; alt. 149m; 1994-02-01; Ferro, L. leg.; (ICN). • 1☿️; Parque Nacional Natural Los Katios, Centro administrativo Sautatá; 7.85, -77.1335; alt. 96m; 2003-05-20; Cansia, A. leg.; pitfall; (IAvH). – Nariño: • 1☿️; Tumaco; 1.7875, -78.7913; alt. 5m; 2015-09-16; (MEPN). – Valle del Cauca: • 1☿️; Anchicaya ; 3.616, -76.909; alt. 350m; 1970-11-01; (MUSENUV). • 1♀; Bajo Anchicaya ; 3.689, -76.94; alt. 270m; 1983-03-01; Quintero, J. leg.; (MUSENUV). • 2☿️; Bajo Anchicaya ; 3.689, -76.94; alt. 270m; 1983-03-01; Quintero, J. leg.; (MUSENUV). • 1♀; Cali; 3.4, -76.5; 1983-02-01; Manzano, M. leg.; (MUSENUV). • 1☿️; San Cipriano, Buenaventura; 3.84, -76.898; alt. 80m; 2002-02-28; Gutiérrez, C. leg.; (MUSENUV). • 1☿️; San Cipriano, Buenaventura; 3.84, -76.898; alt. 80m; 2002-06-08; Gutiérrez, C. leg.; (MUSENUV). COSTA RICA – Limon: • 2☿️; Zent, 23 Km WNW Puerto Limón; 10.0167, -83.2667; alt. 21m; 1958-11-01; Lara, F. leg.; (MZSP). – Puntarenas: • 1☿️; 14 km E Palmar Norte; 8.95, -83.3333; alt. 120m; 1985-08-01; Ward, P. S. leg.; (PSWC). • 1☿️; Parque Nacional Corcovado, Sirena Station; 8.533, -83.533; 1992-06-03; McDonald, M. J. leg.; (AMNH). ECUADOR – Manabi: • 1☿️; Estación Científica Río Palenque; -0.7333, -79.8; alt. 180m; 1980-12-29; Sandoval, S. leg.; (MZSP). – Napo: • 1☿️; Limoncocha; -0.3998, -76.6001; alt. 280m; 1972-06-30; Kazan, P. leg.; (QCAZ). – Zamora Chinchipe: • 2☿️; Paquisha alto, Hito 2, 15 Km SE Fruta del Norte, Cordillera del Cóndor; -3.9003, -78.4829; alt. 2325m; 2008-03-15; Troya, A. leg.; fogging; (MEPN). FRENCH GUIANA – Cayenne: • 1☿️; Base Vie; 5.1667, -52.65; alt. 10m; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Montagne dês Chevaux; 4.7333, -52.4333; alt. 75m; 2011-11-19; Team, S. E. A. G. leg.; (DZUP). NICARAGUA – Región Autónoma del Atlántico Sur: • 1☿️; RN Kahka Creek; 12.671, -83.7175; alt. 30m; 2011-06-06; LLAMA leg.; Malaise; (JTLC). PANAMA – Colón: • 2♂; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2003-10-01; Dejean, A.; et al. leg.; (CPDC). • 1♀; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2004-03-08; Pizon, S. leg.; Malaise; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2522, -79.9894; alt. 96m; 2003-10-27; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2004-10-12; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2003-09-01; Schmidl, J. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2003-10-01; Dejean, A.; et al. leg.; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2004-02-17; Springae, N. D; Pizon, S leg.; Malaise; (CPDC). • 2☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2003-04-01; (CPDC). • 1☿️; Bosque Protector San Lorenzo; 9.2833, -79.9667; alt. 13m; 2003-10-05; Kitching, R. leg.; Light trap; (CPDC). PERU – Cusco: • 1☿️; Quince Mil, km 8; -13.2167, -70.7167; alt. 633m; 2012-08-20; Cavichioli, R.; et al. leg.; Malaise; (DZUP).

Geographic range. Mexico (Chiapas)*, Guatemala, Honduras*, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela*, Guyana*, French Guiana, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia*, Brazil (Acre, Amapá, Bahia, Distrito Federal, Espirito Santo*, Goiás, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pará, Paraná, Piauí*, Rio de Janeiro, Rondônia, Roraima, Santa Catarina, São Paulo, Sergipe), Paraguay*, Argentina (Misiones)*. *: Literature records.

4.2.3. Neoponera dismarginata (Mackay & Mackay 2010)

Figures. 2a (petiole ♀︎); 20: a – e (☿); 31a (distribution).

Pachycondyla dismarginata MacKay & MacKay, 2010: 301, Figs. 111, 256, 257. ☿ holotype, Costa Rica, Heredia Prov., 16 km. N Vol. (Volcán) Barba, 10°17’N, 84 05’W, 950 m., 4-14.vii.1986, J. Longino (leg.) #1380-S, wet forest, workers on vegetation, (MCZC: MCZ-ENT00036273) [image examined, link]. Paratypes: 3 ☿ [same data as for holotype], (INBC, MCZC, WEMC) [not examined]. Note: Collection data transcribed ipsis litteris directly from holotype label.

Combination in Neoponera: Schmidt & Shattuck, 2014: 151.

Status as species: Fernandes et al., 2014: 134.

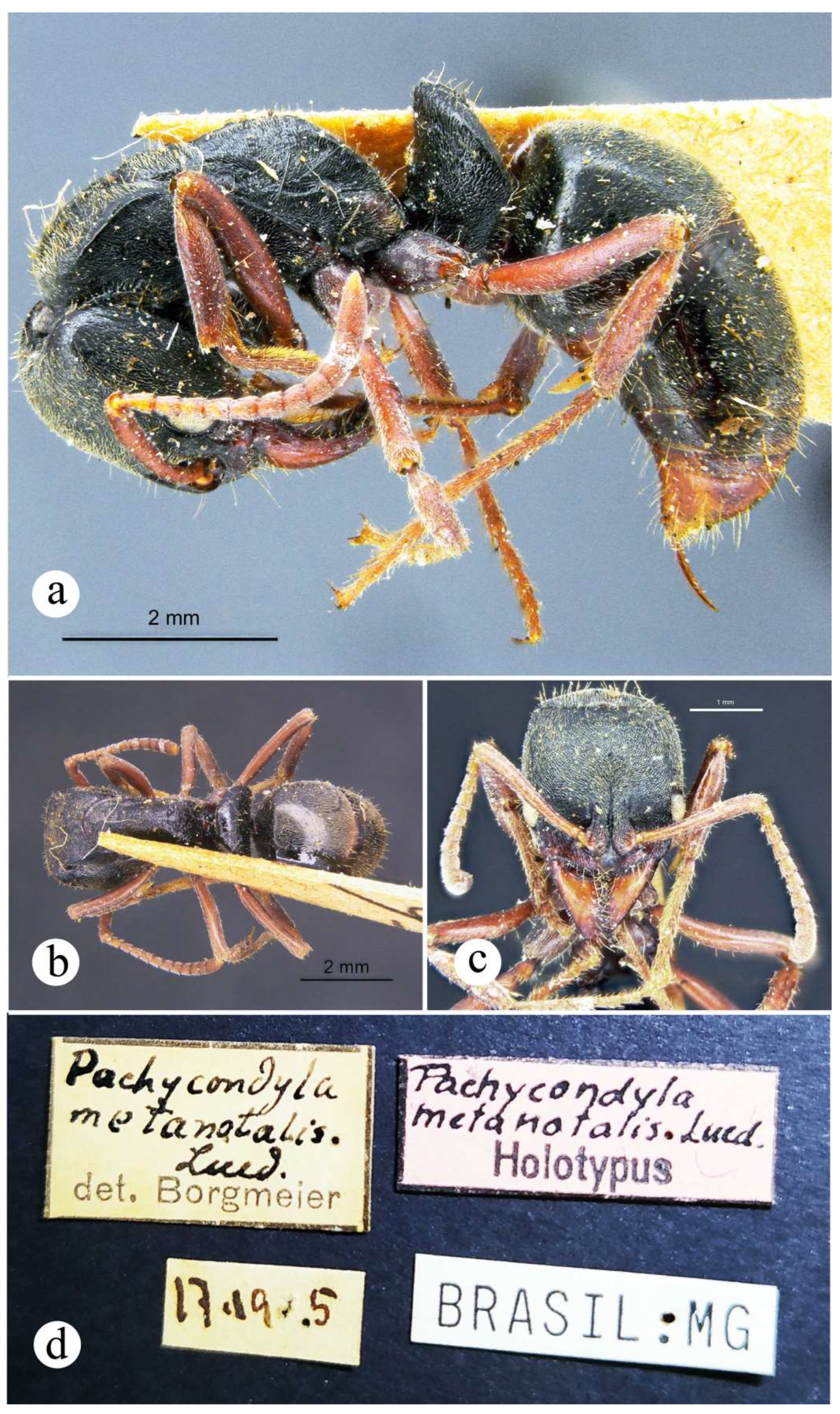

Worker (and probably queen) diagnosis. Head longer than broad in frontal view; malar carina virtually absent, though a tiny longitudinal swelling combined with well-impressed rugae is present anteriorly (Fig. 20e); antennal scape very long, when pulled posterad exceeding posterior head margin by about four times apical scape width (Fig. 20c); eye relatively small (as compared to head length), distance from anterior eye margin to mandibular insertion slightly longer than maximum eye length (Fig. 20e); clypeus bearing well-impressed, irregular longitudinal striae, mid clypeus convex, relatively acute (Fig. 20c); humeral carina present, slightly acute anteriorly, not salient; mesosternal process highly reduced, stump-shaped; metasternal process well-developed as in all congeners of the N. foetida group, dorsally with longitudinal well-impressed striae; posterolateral propodeal margin convex, not carinate (Fig. 20a); petiolar node subtriangular in lateral view, anterior and posterior margins irregularly straight, posterior face convex, nodal top slightly anterior to vertical midline (Fig. 2a, 20a); lateral nodal carina completely absent (Fig. 2a); subpetiolar process with well-developed, acute cusp and relatively flat dome (Fig. 2a); prora very small, slightly discerned laterally, anteriorly blunt (Fig. 2a); appressed pilosity white-brownish, not abundant and composed of tiny hairs (in contrast to most other congeners of the group where these hairs are longer and abundant); cuticle light castaneous.

Worker. Measurements (n = 3): HW: 2.25-2.3; HL: 2.6-2.85; EL: 0.6-0.72; SL: 3.25-3.3; WL: 4.3-4.5; PrW: 1.5-1.75; MsW: 1.0-1.2; MsL: 0.85-0.95; PW: 1.1-1.15; PH: 1.3-1.4; PL: 1.25-1.3; GL: 4.25-4.9; A3L: 1.5-1.75; A4L: 1.75-1.9; A3W: 1.9-2.05; A4W: 2.0-2.05; TLa: 11.7-11.98; TLr: 12.65-13.2. Indices. CI: 80.7-86.54; OI: 26.67-31.09; SI: 141.3-146.67; MsI: 117.65-129.41; LPI: 89.29-100.0; DPI: 88.0-88.46.

Queen and male. Unknown.

Comments. In the N. foetida group, N. dismarginata is the second largest species after N. curvinodis (Fig. 12; ☿ TLa = 11.7 – 12 mm). Since only four specimens were examined, all of them basically equal, no inference about morphological variation is possible for this Costa Rican endemic. Some body features like the long antennal scape, the tiny feebly impressed malar carina, the shape of the node, among others, make this taxon very singular among its congeners in this species-group, but also among species in the genus. Thus, it is unlikely for it to be misidentified with other Neoponera. Only N. apicalis (Latreille) and N. obscuricornis (Emery) show a relatively similar node, but their integument is dull black and the head has large eyes, clearly larger than N. dismarginata. Mackay and Mackay (2010) point out that N. bugabensis and N. insignis show malar carinae which do not reach the anterior eye margin, and because of that they are “placed” with N. dismarginata. Nevertheless, the malar carina of the latter is so poorly developed that it hardly would be closely related to those species based just on this single trait. Longino (2010) mentions that the “cheeks” (= malar region) have distinct carinae which reach the anterior eye margin. This is a typo, however, since the image of a specimen (INBIOCRI002278957) shown just above Longino’s text depicts otherwise.

Figure 20.

Neoponera dismarginata. ☿ (JTL: JTL9295). a. Lateral view; b. Dorsal view; c. Head in frontal view; d. Close-up of head in anterolateral view.

Figure 20.

Neoponera dismarginata. ☿ (JTL: JTL9295). a. Lateral view; b. Dorsal view; c. Head in frontal view; d. Close-up of head in anterolateral view.

Neoponera dismarginata is the putative sister lineage of N. solisi (Troya et al. unpublished), but it is quite different to it. The petiolar node of N. solisi is somewhat block-shaped in lateral view with scarce appressed pubescence and the posterior face is glabrous, while the node of N. dismarginata is subtriangular in lateral view and carries relatively abundant appressed pilosity.

Distribution notes. Populations of N. dismarginata apparently are not rare in Costa Rica from where it has been collected in a number of sites since 1984 up to 2015 according to AntWeb.org. It appears though that this is a true endemic for that region since no other records have been found in several other Central American countries where some sampling campaigns have been carried out (see for example the LLAMA and ADMAC projects led by J. Longino)

Natural history notes. See Longino (2010).

Material examined. 4☿️. COSTA RICA – Heredia: • 1☿️; 16km N Vol. Barba; 10.2833, -84.0833; alt. 950m; 1986-07-09; (MCZC). – Limón: • Cerro Platano, 26km WSW Limón; 9.8682, -83.2408; alt. 1140m; 2015-06-16; Longino, J. leg.; hand collected; (MUCR). • 1☿️; Cerro Platano, 26km WSW Limón; 9.8682, -83.2408; alt. 1140m; 2015-06-16; Longino, J. leg.; hand collected; (MUCR). – Puntarenas: • 2☿️; Wilson Botanical Garden, 4km S San Vito; 8.7833, -82.9667; alt. 1200m; 1990-03-22; Longino, J. leg.; (JTLC).

Geographic range. Costa Rica.

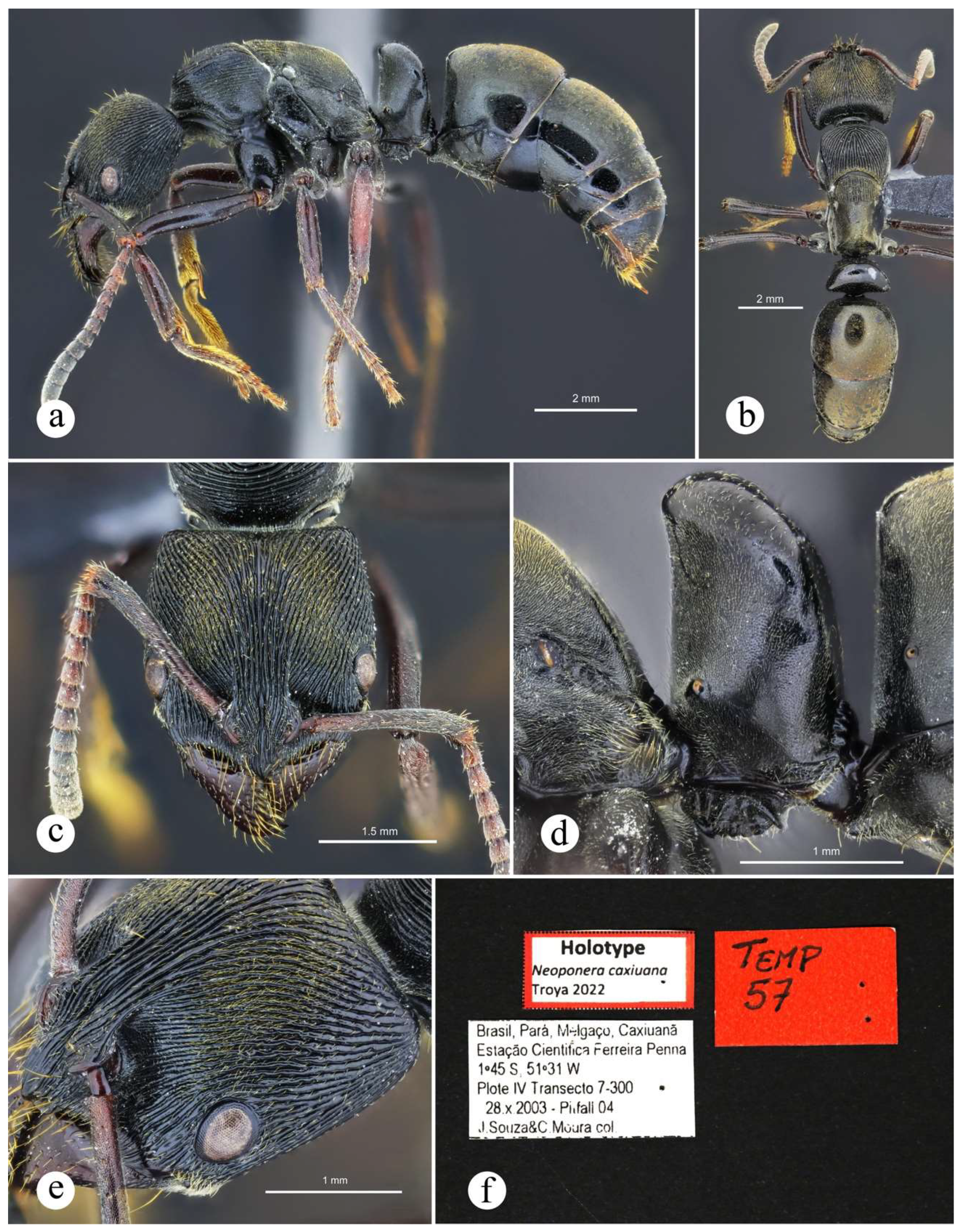

4.2.4. Neoponera fisheri (Mackay & Mackay 2010)

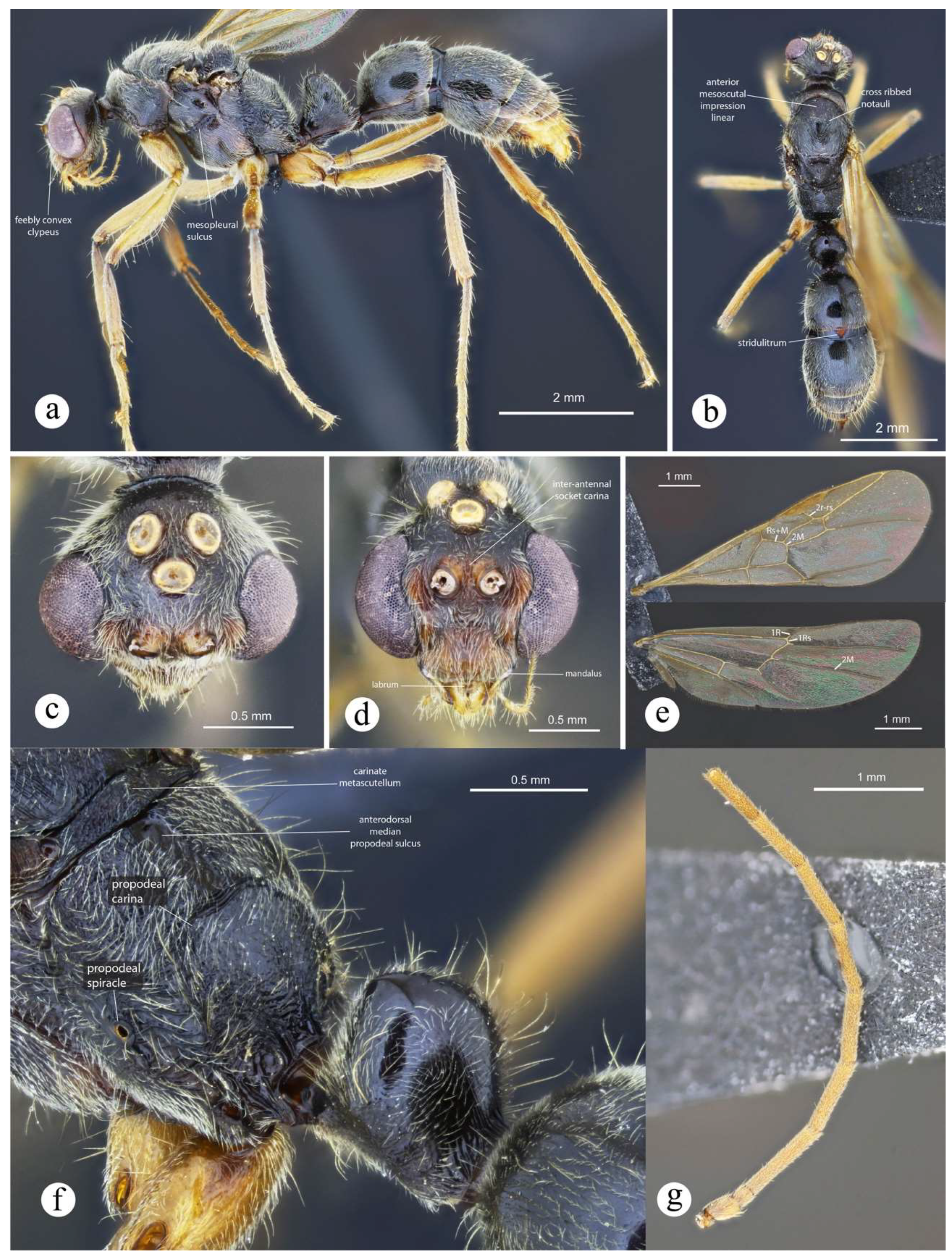

Figures. 1a (head ♀︎); 21: a – c (♀︎); 31a (distribution).

Pachycondyla fisheri MacKay & MacKay, 2010: 328, Figs. 30, 32, 34, 278, 279, 293, 451- 454. ☿ holotype, Panama, Colon Prov., Santa Rita Ridge, 9°21’N, 79°47’W, 250 m., 24.iii.189, B.L. Fisher (leg.), rain forest ex Cecropia hispidissima, (CASC: CASENT092338) [image examined, link]. Paratypes: 9 ☿, 6♀, 2 ♂︎, [same data as for holotype], (CASC, GFMP, IAVH, MCZC, USNM, WEMC) [not examined]. Note: Paratype from IAVH absent from collection.

Combination in Neoponera: Schmidt & Shattuck, 2014: 151.

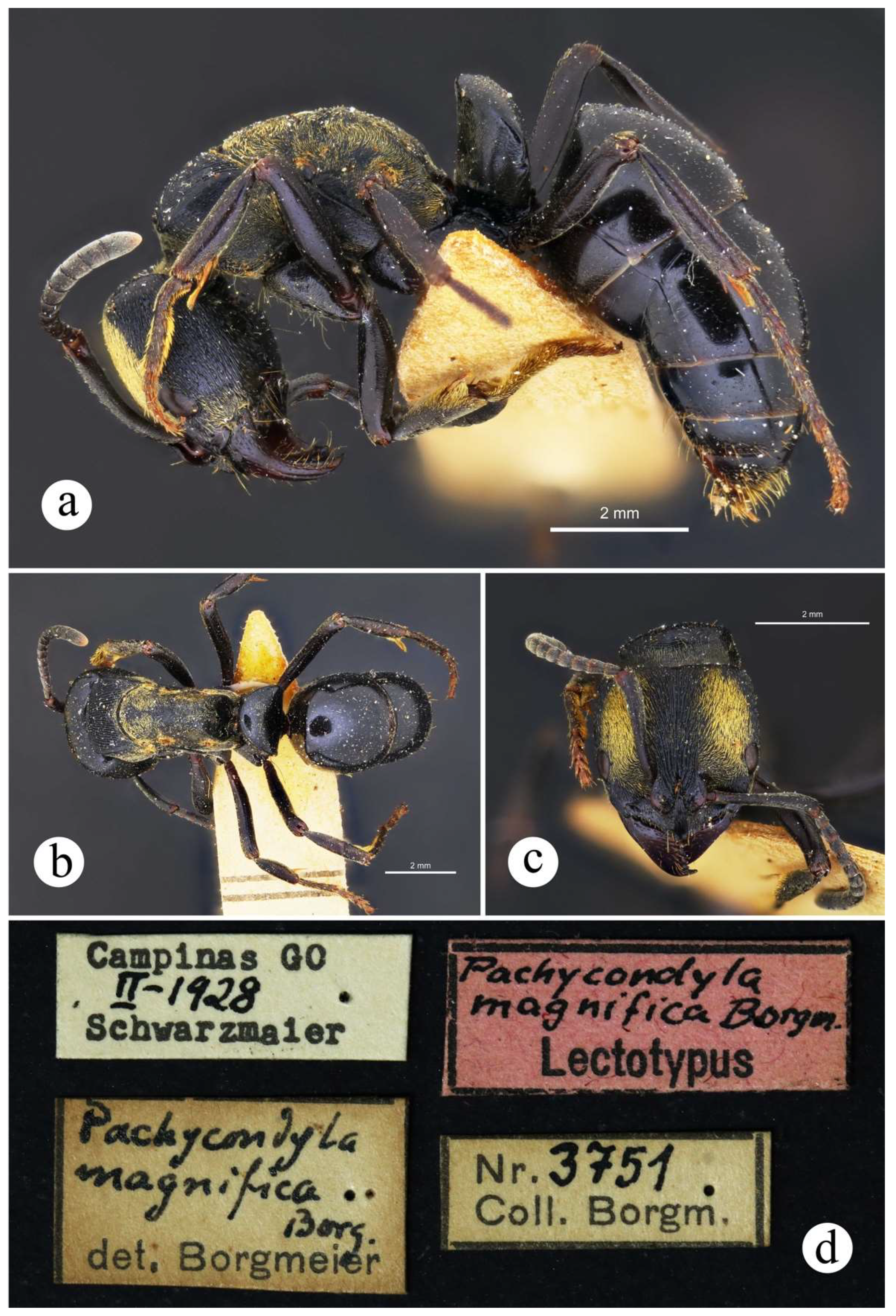

Worker and queen diagnosis. Head subtrapezoidal, narrowed anteriorly; masticatory margin of mandible with eight to nine teeth, gradually decreasing in size, denticles absent, except for one proximal (Fig. 21b); eye, especially on workers, less globose than in all other congeners in the N. foetida group, and placed slightly anteriorly on head; mid clypeus strongly concave, somewhat like harelip (Fig. 21b); antennal scape, when pulled posterad, fails to reach posterior head margin by about one apical scape width (Fig. 1a, 21b); malar carina present but tiny, feebly protuberant anteriorly (Fig. 1a, 21b); humerus weakly marginate anteriorly, particularly on worker, but a true carina is absent; notopropodeal groove cross ribbed in workers only; mesopleural groove tenuously impressed on workers, and vestigial on queens (Fig. 21a); meso- and metasternal processes well-developed, fang-shaped; in lateral view, petiolar node somewhat block-shaped with broadly curving margin posteriorly in workers (link), and subtriangular in queens, with convex top (Fig. 21a); posterolateral nodal margin lacking carina (Fig. 21a); posterior nodal face glabrous (Fig. 5a); subpetiolar process smooth, lacking horizontal striae, instead bearing one or two longitudinal carinae; pale yellowish appressed pilosity although covering body surface, formed by fine, thin hairs, so that cuticle is clearly discerned.

Figure 21.

Neoponera fisheri. ♀︎ (PSWC: CASENT0843089), Panama, Coclé. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 21.

Neoponera fisheri. ♀︎ (PSWC: CASENT0843089), Panama, Coclé. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Worker. Measurements (n = 1): HW: 2.6; HL: 2.75; EL: 0.65; SL: 1.9; WL: 4.25; PrW: 1.6; MsW: 1.3; MsL: 1.1; PW: 1.35; PH: 1.15; PL: 1.2; GL: 5.09; A3L: 1.65; A4L: 1.95; A3W: 1.95; A4W: 2.25; TLa: 11.8; TLr: 13.29. Indices. CI: 94.55; OI: 25; SI: 73.08; MsI: 118.18; LPI: 104.35; DPI: 112.5.

Queen. Measurements (n = 1): HW: 2.75; HL: 2.85; EL: 0.8; SL: 2.1; WL: 4.55; PrW: 2.2; MsW: 1.2; MsL: 0.8; PW: 1.5; PH: 1.2; PL: 1.2; GL: 5.66; A3L: 2.0; A4L: 2.15; A3W: 2.15; A4W: 2.5; TLa: 12.75; TLr: 14.26. Indices. CI: 96.49; OI: 29.09; SI: 76.36; MsI: 150; LPI: 100; DPI: 125.

Male. Described by Mackay and Mackay (2010).

Comments. Neoponera fisheri is a relatively large species in the N. foetida group (Fig. 12). Few specimens are known, all of them collected in three sites from Panama (AntWeb.org), their body color varies from castaneous to black. Besides this, the overall morphology seems to be quite similar among the scant material available. Nevertheless, a queen from Coclé (CASENT0843089) shows a mid-clypeal triangular-shaped concavity carrying horizontal striae in frontal view, which is different from the equivalent structure in a worker from Nusagandi (MZSP) where this concavity is subrectangular and lacks striae. In addition, this same worker shows an anterior tiny ocellus (about two times smaller than those of the queen) and two posterior ocellar pits (see below a discussion about this).

Neoponera fisheri is another peculiar species in terms of morphology in the N. foetida group. Mackay and Mackay (2010) believed this as a possible link between species in the N. aenescens and the N. foetida groups. They placed N. fisheri in the former although without certainty, and further suggested that it may deserve its own complex. Mackay and Mackay’s view about this species was in some way accurate because it is “almost” a link between two species-groups, but these are the N. crenata and the N. foetida groups. In the phylogeny of the genus, N. fisheri is placed at the base of the latter clade, and sister to all species in it (Troya et al., unpublished). From an evolutionary perspective, this placement makes sense since this lineage shares scant traits with its clade partners, namely the shape of head sculpture, and the fang-shaped metasternal process with broad lobes. Of these, only the latter is considered apomorphic between all species in the N. foetida group. Nevertheless, even with a well-supported phylogeny at hand we would refrain to suggest that the morphology of N. fisheri depicts the ancestral features of the remaining clade members. Whether these unusual features, like the short antennal scapes (unique among species in the genus), the strongly concave mid clypeus, the fused mesopleural plates of the queen, among others, represent ancestral states which have been lost in all other species of the group, or may these traits be independently gained as a function of the environment, for example through adaptive speciation, is a topic which warrants further research.

Out of the N. foetida group, another species with unique morphology features (among its clade partners) is N. luteola which belongs to the N. crenata group. Interestingly, some body regions of both N. fisheri and N. luteola are similar, like the outline of the head bearing somewhat flat eyes (less globose than in most other Neoponera belonging to these two sister clades), the shape and sculpture of the node, and the shape of the mesosoma. Current evidence supports a potential partnership between Neoponera luteola and some Cecropia plants in South America (Gutiérrez-Valencia et al. 2017). No (sufficient) evidence is still available for N. fisheri but it could well represent a similar case since specimens were collected inside Cecropia plants in different sites and years in Panama.

Natural history notes. Almost nothing is known about the biology and ecology of N. fisheri. The labels of the two examined specimens show that the worker and other nestmates (queen and larva) were collected by Phil Ward in three adjacent internodes of a Cecropia insignis (Urticaceae). The other group of individuals, consisting of the type material which was not physically examined here, was collected by Brian Fisher inside a C. hispidissima.

In regards to the ocellus observed in the worker from Nusagandi: ocelli-bearing workers is a relatively rare condition in Neoponera, but it has been seen in for example, members of the N. apicalis (N. apicalis, N. cooki), and N. aenescens groups (N. aenescens, N. carbonaria), being more frequent in N. cooki. Ocelli are usually found in worker ants which show crepuscular and night foraging behavior; these allow them capturing more light in dimly lit conditions (Narendra and Ribi 2017). In contrast to members of the N. apicalis and N. aenescens groups which are predominantly epigeic, where light incidence on the forest floor is reduced as compared to upper forest strata, most species in the N. foetida group, including N. fisheri, are arboreal. Apparently, the ocelli in workers of this group are quite rare, and thus far, has not been seen in workers of the arboreal N. crenata group, except for few specimens of N. goeldii (pers. obs.). Neoponera goeldii is arguably a nocturnal arboreal forager (Orivel et al. 2000). Perhaps, some N. fisheri workers forage at dawn or during the night, more frequently though than others with different schedule in their foraging behavior. Longino ( 2010) observed N. dismarginata workers in Costa Rica foraging at night. However, ocelli are thus far apparently absent from workers of this latter species.

Material examined. 3☿️, 2♀, 1♂. PANAMA – Coclé: • 1♀; 6 km NNW El Copé, Parque Nacional Omar Torrijos; 8.6719, -80.595; alt. 840m; 2015-01-22; Ward, P. S. leg.; hand collected; (PSWC). • 1☿️; 6 km NNW El Copé, Parque Nacional Omar Torrijos; 8.6719, -80.595; alt. 840m; 2015-01-22; Ward, P. S. leg.; hand collected; (DZUP). • 6 km NNW El Copé, Parque Nacional Omar Torrijos; 8.6719, -80.595; alt. 840m; 2015-01-22; Ward, P. S. leg.; hand collected; (DZUP). – Panama: • 1☿️; 42km W of Tupile, Reserva Nusagandi; 9.3489, -78.966; alt. 346m; 1989-10-26; Fisher, B. leg.; hand collected; (MZSP). • 1♂; Puerto Colón, Santa Rita ridge; 9.35, -79.7833; alt. 250m; 1989-03-24; Fisher, B. leg.; hand collected; (UTEP) [image from AntWeb]. • 1♀; Puerto Colón, Santa Rita ridge; 9.35, -79.7833; alt. 250m; 1989-03-24; Fisher, B. leg.; hand collected; (UTEP). • 1☿️; Puerto Colón, Santa Rita ridge; 9.35, -79.7833; alt. 250m; 1989-03-24; Fisher, B. leg.; hand collected; (CAS).

Geographic range. Panama.

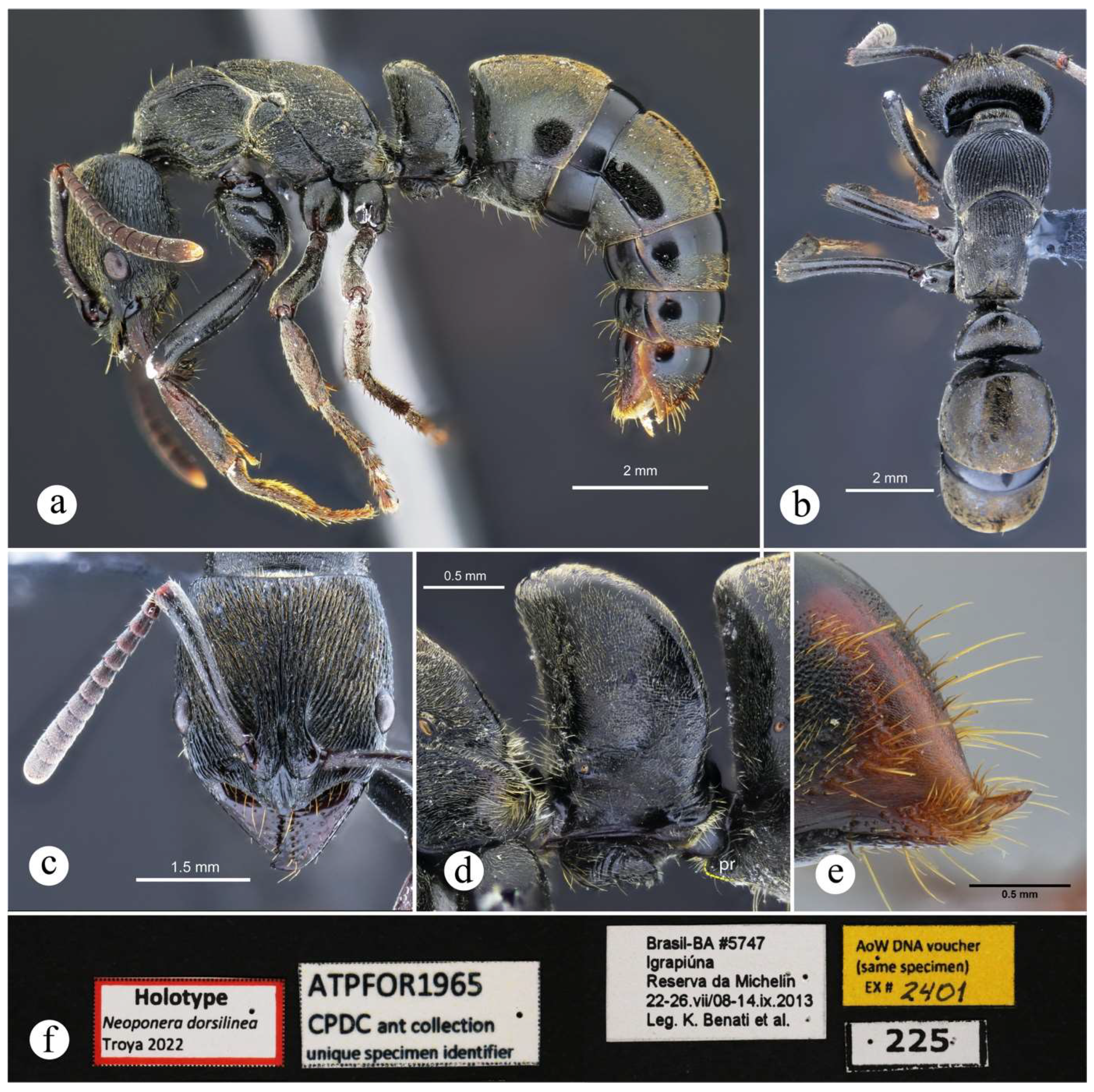

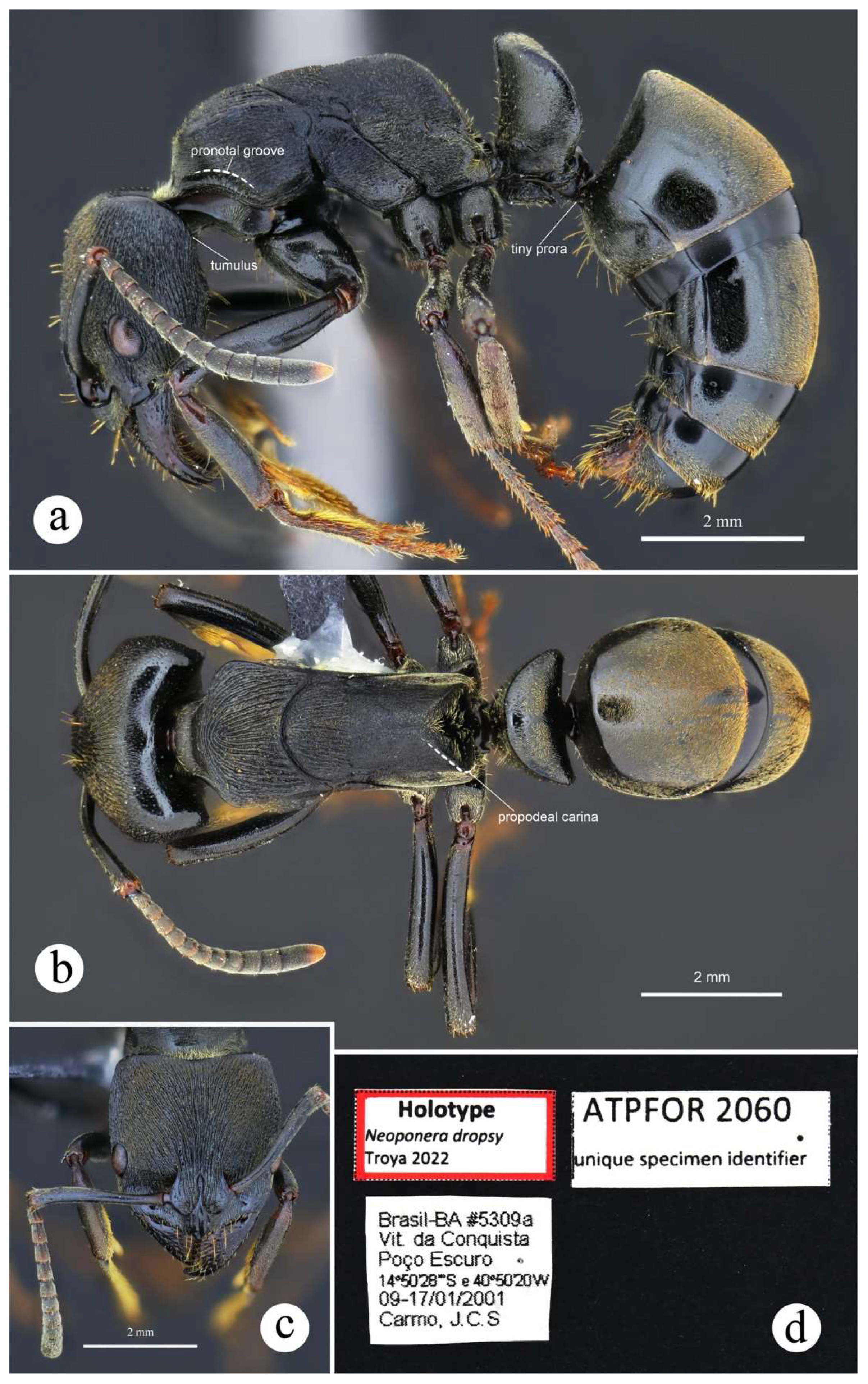

4.2.5. Neoponera foetida (Linnaeus, 1758)

Figures. 3a (petiole ☿); 22: a – c (♀︎); 31b (distribution)

Formica foetida Linnaeus, 1758: 582 ♀︎ “America meridionali” [no locality given], Rolander [leg.], (ZMLS) [absent from collection].

Combinations. In Ponera: Smith, 1858: 95; in Pachycondyla: Roger, 1863: 18; Brown, 1995: 305; in Neoponera: Emery, 1901: 47; Schmidt & Shattuck, 2014: 151.

Status as species. Linnaeus, 1767: 965; Roger, 1860: 312 [redescription]; MacKay & MacKay, 2010: 332 [redescription].

Neoponera pedunculata Smith, 1858: 96. Syn. nov.

Senior synonym of Neoponera lobata: Retzius 1783: 75.

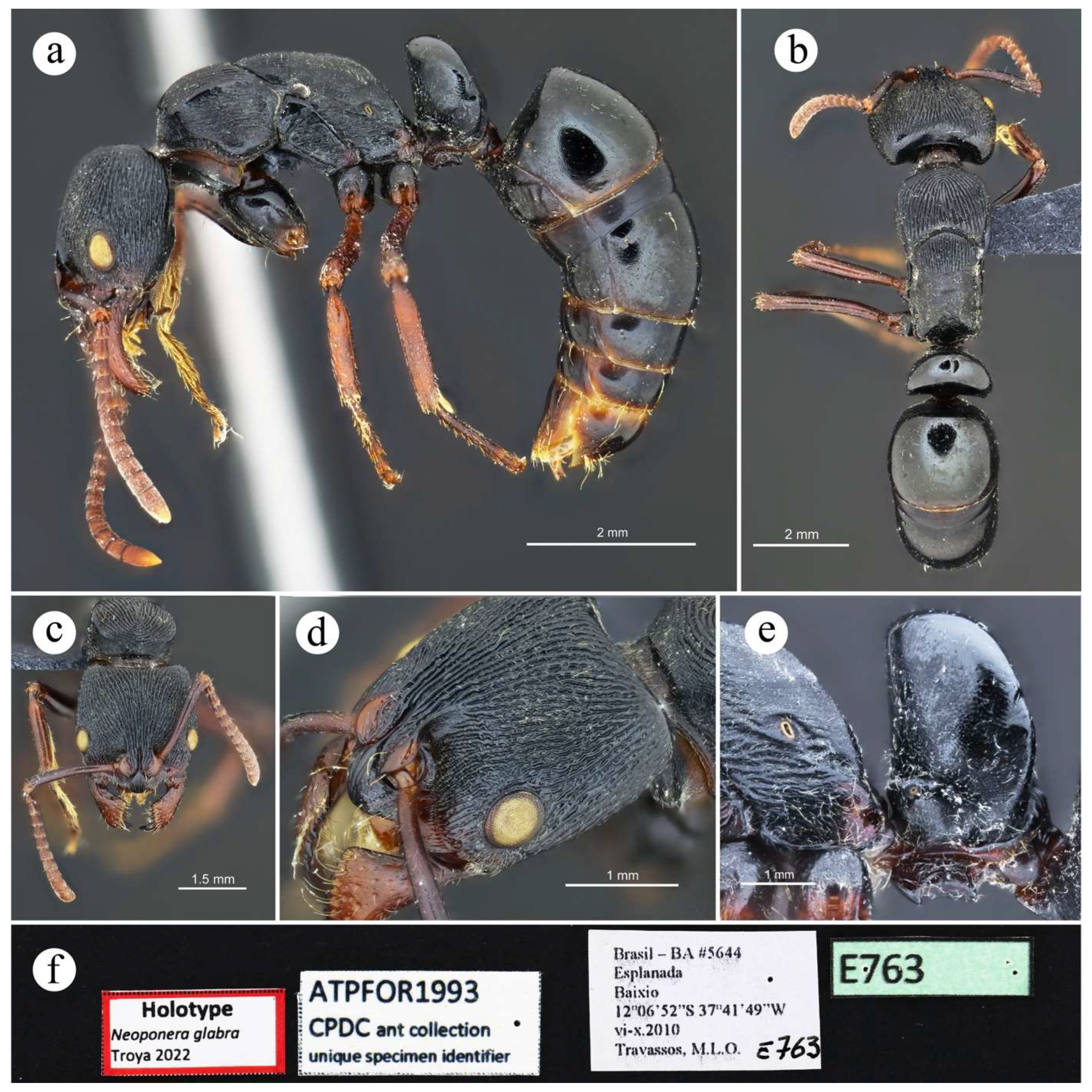

Worker and queen diagnosis. Head subrectangular; antennal scapes, when pulled posterad, exceeding posterior head margin by about 1.5 times apical scape width; humeral carina salient, shelf-like (Figs. 7c, 22a); petiolar node block-shaped, with dorsal margin horizontally straight up to about the mid region and immediately broadly curving posterad, anterior margin mostly straight (Figs. 3a, 22a); node covered by usually gross horizontal striae, except by mid ventral region on lateral face (Fig. 3a); prora keel-shaped, tip usually acute, directed ventrad.

Worker. Measurements (n = 12): HW: 2.0-2.45; HL: 2.2-2.75; EL: 0.6-0.75; SL: 1.9-2.55; WL: 3.45-4.45; PrW: 1.5-1.9; MsW: 0.8-1.1; MsL: 0.75-0.97; PW: 1.1-1.5; PH: 0.9-1.46; PL: 0.95-1.19; GL: 3.7-4.44; A3L: 1.25-1.75; A4L: 1.35-1.85; A3W: 1.35-2.15; A4W: 1.5-2.2; TLa: 9.2-11.75; TLr: 10.3-12.46. Indices. CI: 86.96-98.0; OI: 25.53-35.0; SI: 95.0-107.5; MsI: 94.12-122.22; LPI: 79.4-127.78; DPI: 100.0-136.36.

Figure 22.

Neoponera foetida. ♀︎ (MPEG: ATPFOR1848), Brazil, Amazonas. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Figure 22.

Neoponera foetida. ♀︎ (MPEG: ATPFOR1848), Brazil, Amazonas. a. Lateral view; b. Head in frontal view; c. Dorsal view.

Queen. Measurements (n = 2): HW: 2.2-2.75; HL: 2.45-2.8; EL: 0.6-0.7; SL: 2.25-2.75; WL: 4.25-5.09; PrW: 1.75-2.2; MsW: 1.0-1.65; MsL: 0.7-1.75; PW: 1.4-1.55; PH: 1.15-1.2; PL: 1.25-1.25; GL: 4.3-5.66; A3L: 1.5-1.95; A4L: 1.6-2.2; A3W: 2.1-2.3; A4W: 2.2-2.45; TLa: 11.05-13.29; TLr: 12.25-14.8. Indices. CI: 89.8-98.21; OI: 25.45-27.27; SI: 100.0-102.27; MsI: 94.29-142.86; LPI: 104.17-108.7; DPI: 112.0-124.0.

Male. Unknown.

Comments. Neoponera foetida is a medium-sized taxon in the N. foetida group (Fig 12; (☿ TLa = 9.2 – 11.75 mm; ♀︎TLa = 11 – 13.29 mm). Because of the coarse striae covering most of the petiolar node, this species is fairly easy to distinguish from all others in the group. Another potentially apomorphic populational trait is the salient humeral carina, which is slightly less protruding in specimens from Central America than those from South America. Other than that, the overall morphology of N. foetida is typical of this group, and it shows closer resemblance to the morphology of N. villosa, N. curvinodis, N. inversa, and N. zuparkoi, with which it forms a clade (Troya et al., unpublished).

This is the only species in the N. foetida group for which, thus far there are no clues about the location of the primary type material for any caste, except for the male which is still unknown. The ZMLS collection in Sweden could be a probable candidate, however, while writing this manuscript the museum staff confirmed to us it is not there either (ZMLS staff, pers. comm.). Roger (1860) redescribed this species based on a queen but this is also apparently lost since it is not vouchered at the MNHU collection. Despite the nodal striae being conspicuous in N. foetida, these are almost identically displayed on the node of at least two other Neoponera: N. striatinodis (Emery) and an unidentified Neoponera from Orellana, Ecuador, which belongs to the N. crenata group (collection codes: MEPNINV3375, MEPNINV28815). Neoponera foetida is today relatively easy to identify, but probably it was not in the past due to the scarcity of reference specimens in collections. It is thanks to Roger’s (1860) redescription and to De Geer's (1773) illustration of the nodal striae of N. lobata (currently senior synonym of N. foetida) that this species is now identifiable, and most importantly, diagnosable. For this reason, no attempt is made here to designate a neotype. The reader can use the present diagnosis and taxonomic key to recognize this species. Fernandes et al. (2014), Mackay and Mackay (2010), and AntWeb.org images (link) are also useful resources.