Submitted:

05 April 2023

Posted:

05 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Materials

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Nests Collection and Caste Structure Laboratory Assessment

2.3. Estimation of Eggs Number per Nest

2.4. Estimation of Individual Population Size from Matured Colonies

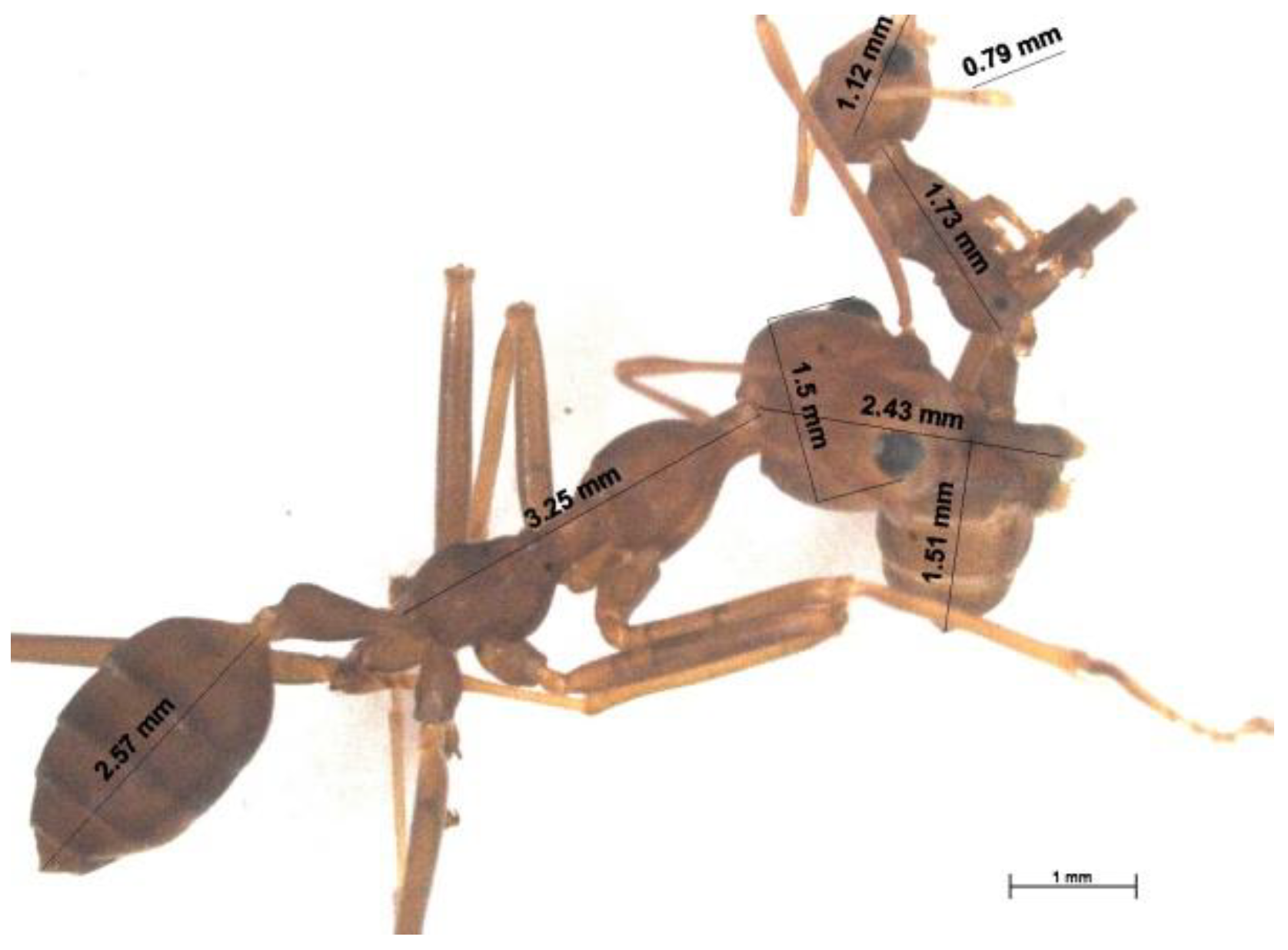

2.5. Individual Worker Caste Measurements

2.6. Monitoring Reproductive Caste Emergence

2.7. Intermediate Workers Evaluation

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Oecophylla Smaragdina Colony Social Structure Description

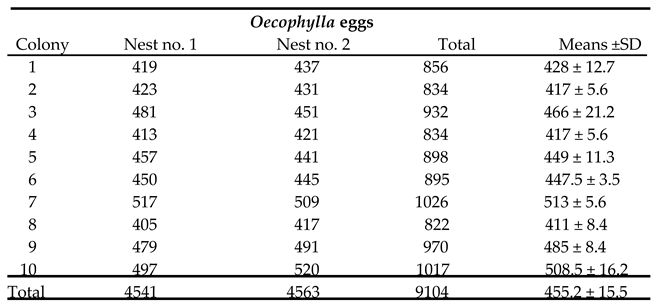

4.2. Colonies Eggs Count Estimation

4.3. Colony Caste Composition-Description

4.4. Colonies Dissected Nest Content – Reproductive Population Size Estimation

4.5. Workers Caste Description

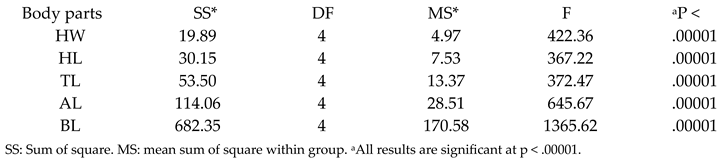

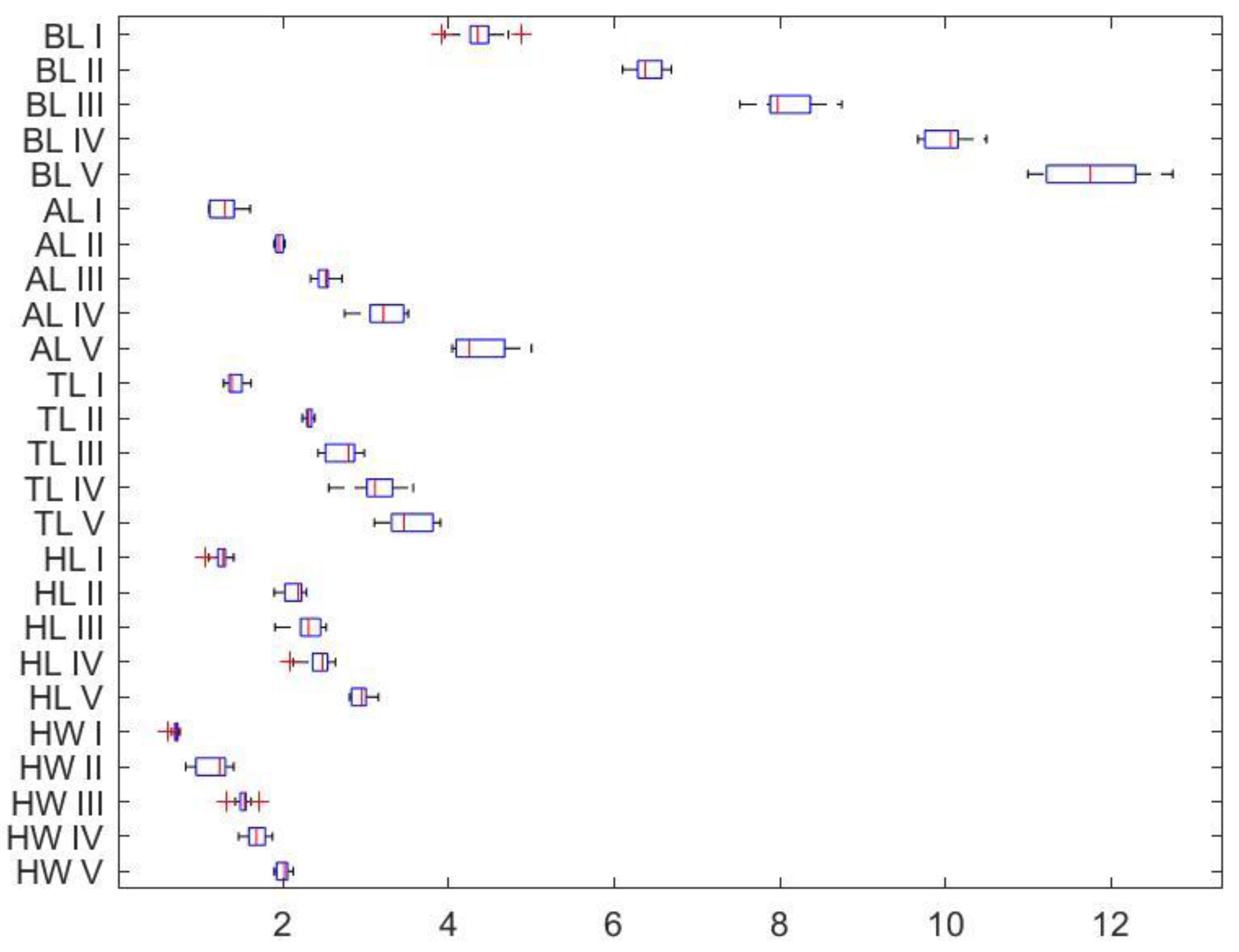

4.6. Worker Castes Body Size Analysis

| HW mm | HL mm | TL mm | AL mm | BL mm | Worker Castes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.99 | 2.93 | 3.53 | 4.38 | 11.8 | V |

| 1.68 | 2.43 | 3.14 | 3.20 | 9.99 | IV |

| 1.51 | 2.28 | 2.73 | 2.50 | 8.10 | III |

| 1.15 | 2.12 | 2.30 | 1.95 | 6.41 | II |

| 0.70 | 1.25 | 1.411 | 1.27 | 4.36 | I |

| ±0.49 | ±0.61 | ±0.81 | ±1.19 | ±2.92 | ±SD |

| 0.223 | 0.27 | 0.365 | 0.53 | 1.30 | SEM |

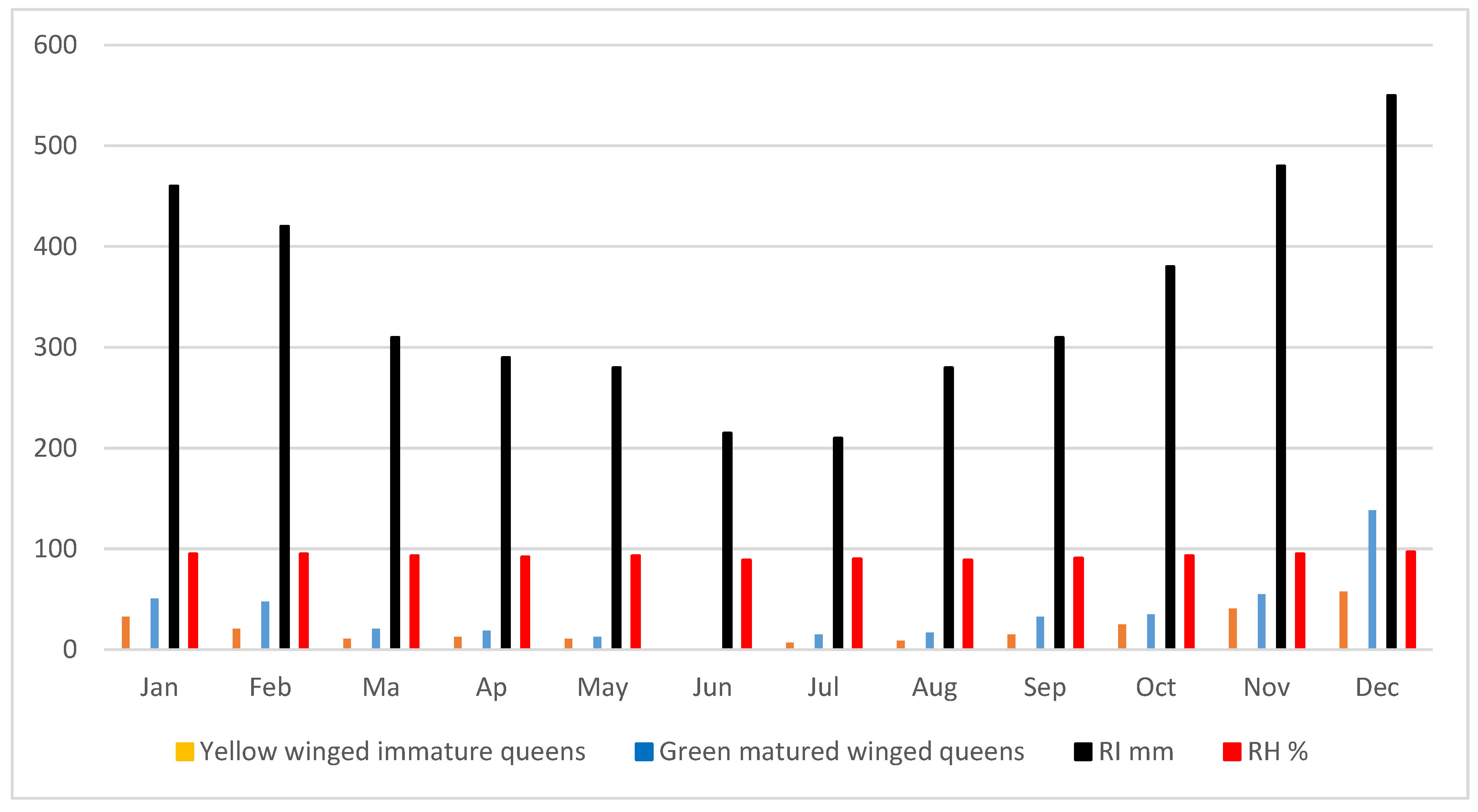

4.7. Emergence-Abundance of Reproductive Individuals

|

Months |

Jan |

Feb |

Ma |

Ap |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

Means ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow winged queens |

33 |

21 |

11 |

13 |

11 |

0 |

7 |

9 |

15 |

25 |

41 |

58 |

20.3 ±16.5 |

| Green winged queens |

51 |

48 |

21 |

19 |

13 |

0 |

15 |

17 |

33 |

35 |

55 |

138 |

37 ±36 |

| Gravid queen | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Drone males | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 250 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| *RI mm | 460 | 420 | 310 | 290 | 280 | 215 | 210 | 280 | 310 | 380 | 480 | 550 | 348.75 ±108.3 |

|

1RH % Locations |

95 MPOB TIP |

95 ** |

93 Felda PK |

92 ** |

93 ** |

89 Felda GBP |

90 MPOB SB |

89 UM |

91 Felcra Johor |

93 Felcra Johor |

95 Felda GBP |

97 UM |

92.6 ±2.5 |

| Colony No. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

Means ±SD |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young colony winged queens/nest Brood nests Total queens/colony Older Colony Winged queens/nest |

9 11 99 19 |

8 9 72 21 |

11 14 143 17 |

10 13 110 21 |

12 16 156 31 |

8 10 64 25 |

7 9 63 17 |

9 13 108 15 |

11 15 132 13 |

12 18 159 35 |

9. 7 ±1.76 12.9 ±2.9 111.8 ±36.5 20.2 ±7.04 |

||

|

Brood nests Total queens/ colony *Drone males |

25 251 |

30 269 |

23 234 |

34 283 |

41 377 |

35 291 |

24 245 |

21 216 |

19 192 |

47 403 |

28.32 ±9.2 257.7 ±67.2 N/A |

4.8. Comparative Novel Intermediate Workers Behaviours

5. Discussion

5.1. O. smaragdina Colony Social Structure – Novel Intermediate Workers Caste

5.2. Novel Intermediate Workers Behaviours

6. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

References

- Advento, A. D., Yusah, K. M., Naim, M., Caliman, J. P., & Fayle, T. M. (2022a). Which Protein Source is Best for Mass-Rearing of Asian Weaver Ants?. Journal of Tropical Biology & Conservation (JTBC), 19, 93-107. [CrossRef]

- Advento, A. D., Yusah, K., Salim, H., Naim, M., Caliman, J. P., & Fayle, T. (2022b). The first record of the parasitic myrmecophilous caterpillar Liphyra brassolis (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) inside Asian weaver ant (Oecophylla smaragdina) nests in oil palm plantations. Biodiversity Data Journal, 10, e83842. [CrossRef]

- AntWeb. Version 8.64.2. California Academy of Science, online at https://www.antweb.org. Accessed 22 September 2021.

- Azuma, N., Kikuchi, T., Ogata, K., & Higashi, S. (2002). Molecular phylogeny among local populations of weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina. Zoological Science, 19(11), 1321-1328. [CrossRef]

- Azuma, N., Ogata, K., Kikuchi, T., & Higashi, S. (2006). Phylogeography of Asian weaver ants, Oecophylla smaragdina. Ecological Research, 21(1), 126-136. [CrossRef]

- Barsagade, D. D., Masram, P. P., & Nagarkar, D. A. (2020). Surface ultra-structural studies on antennae in polymorphs of weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina; Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with reference to sensilla. Indian Journal of Agricultural Research, 54(5), 555-562. [CrossRef]

- Bochynek, T., & Robson, S. K. A. (2014). Physical and Biological Determinants of Collective Behavioural Dynamics in Complex Systems: Pulling Chain Formation in the Nest-Weaving Ant Oecophylla smaragdina. PLoS ONE, 9(4). [CrossRef]

- Chapuisat, M., & Keller, L. (2002). Division of labour influences the rate of ageing in weaver ant workers. Proceedings of Biological Sciences, 269(1494), 909–913. [CrossRef]

- Crozier, R. H., Schlüns, E. A., Robson, S. K. A., & Newey, P. S. (2010). A masterpiece of evolution Oecophylla weaver ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News, 13, 57–71.

- Dejean, A., Corbara, B., Orivel, J., & Leponce, M. (2007). Rainforest canopy ants: the implications of territoriality and predatory behavior. Functional Ecosystems and Communities, 1(2), 105-120.

- Dejean, A., Ryder, S., Bolton, B., Compin, A., Leponce, M., Azémar, F.,... & Corbara, B. (2015). How territoriality and host-tree taxa determine the structure of ant mosaics. The Science of Nature, 102(5-6), 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Exélis, M. P & Azarae, H. I. (2013). Studies on the predatory activities of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on Pteroma pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in oil palm plantations in Teluk Intan, Perak (Malaysia). Asian Myrmecology, 5, 163–176.

- Exélis, M. P. (2015). An ecological study of Pteroma pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae): in oil palm plantation with emphasis on the predatory activities of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on the bagworm. 2013. Masters. Dissertation, Universiti of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia.

- Exélis, M. P., Ramli, R., Ibrahim, R. W., & Idris, A. H. (2023). Foraging Behaviour and Population Dynamics of Asian Weaver Ants: Assessing Its Potential as Biological Control Agent of the Invasive Bagworms Metisa plana (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in Oil Palm Plantations. Sustainability, 15(1), 780. [CrossRef]

- Greenslade, P. J. M. 1972. Comparative ecology of four tropical ant species. Insectes Sociaux, 19, 195–212. [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B. (1983). Territorial behavior in the green tree ant (Oecophylla smaragdina). Biotropica, 15(4), 241-250. [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B. (1998). Cooperation and Communication of Weaver Ants (Oecophylla). Jiussi News, 40.

- Hölldobler, B., & Wilson, E. O. (1990). The Ants. Belknap Press, Cambridge.

- Kamhi, J. F., Nunn, K., Robson, S. K. A., & Traniello, J. F. A. (2015). Polymorphism and division of labour in a socially complex ant: neuromodulation of aggression in the Australian weaver ant, Oecophylla smaragdina. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282(1811). [CrossRef]

- Kümmerli, R., & Keller, L. (2009). Patterns of split sex ratio in ants have multiple evolutionary causes based on different within-colony conflicts. Biology Letters 5, 713–716. [CrossRef]

- Lim, G. T. (2007). Enhancing the weaver ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), for biological control of a shoot borer, Hypsipyla robusta (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), in Malaysian mahogany plantations. Virginia Tech University electronic Doctoral Dissertation. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/handle/10919/26850.

- Lokkers, C. (1990). Colony dynamics of the green tree ant (Oecophylla smaragdina FAB.) in a seasonal tropical climate. – PhD thesis, James Cook University of North Queensland, Townsville, Queensland, 301.

- Mahima, K. V., Anand, P. P., Seena, S., Shameema, K & Manogem, E. M. (2021). Caste-specific phenotypic plasticity of Asian weaver ants: Revealing the allometric and non-allometric component of female caste system of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) by using geometric morphometrics. Sociobiology, 68(2), 5941. http://periodicos.uefs.br/index.php/sociobiology/article/view/5941/5904 . [CrossRef]

- Masram, P. P., & Barsagade D. D. (2021). Morphological and surface ultra-structural studies of legs in polymorphs of weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) with reference to sensilla. International Journal of Zoological Investigations, 7, 26-39. [CrossRef]

- MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox. (2021). The Mathworks Inc. Natick, Massachusetts, USA.

- Meunier, J., West, S. A., & Chapuisat, M. (2008). Split sex ratios in the social Hymenoptera: a meta-analysis. Behavioral Ecology, 19(2), 382–390. [CrossRef]

- Nene, W., Rwegasira, G. M., Mwatawala, M., Nielsen, M. G., & Offenberg, J. (2016a). Foraging behavior and Preferences for Alternative Supplementary Feeds by the African Weaver Ant, Oecophylla longinoda Latreille (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 50, 117-128. [CrossRef]

- Nene, W. A., Rwegasira, G. M., Nielsen, M. G., Mwatawala, M., & Offenberg, J. (2016b). Nuptial flights behavior of the African weaver ant, Oecophylla longinoda Latreille (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and weather factors triggering flights. Insecte Sociaux, 63, 243–248. [CrossRef]

- Newey, P. S., Robson, S. K. A & Crozier, R. H. (2010). Weaver ants Oecophylla smaragdina encounter nasty neighbours rather than dear enemies. Ecology, 91(8), 2366-2372.

- Nielsen, M. G., Peng, R., Offenberg, J., & Birkmose, D. (2015). Mating strategy of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in northern Australia. Austral Entomology, 55(3), 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Offenberg, J. (2015). Ants as tools in sustainable agriculture. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(5), 1197–1205. [CrossRef]

- Peng, R., Christian, K., & Gibb, K. (1998). How many queens are there in mature colonies of the green ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius)? Australian Journal of Entomology, 37(3), 249-253.

- Pfeiffer, M., Ho, C.T., & Lay, T. C. (2007). Exploring arboreal ant community and co-occurrence patterns in plantations of oil palms (Elaeis guineensis) in Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia. In structuring of animal communities: Interspecific interactions and habitat selection among ants and small mammals. Habilitationsschrift zur Erlangung der Venia Legendi an der Universität Ulm. Fakultät für Naturwissenschaften. http://www.antbase.net/pdf/pfeiffer-habil.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M., Ho, C. T., & Chong Lay, T. (2008). Exploring arboreal ant community composition and co-occurrence patterns in plantations of oil palm Elaeis guineensis in Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia. Ecography, 31(1), 21-32. [CrossRef]

- Pimid, M., Hassan, A., Tahir, N. A., & Thevan, K. (2012). Colony Structure of the Weaver Ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology, 59(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Pinkalski, C., Damgaard, C., Jensen, K. V, Gislum, R., Peng, R., & Offenberg, J. (2015). Non-destructive biomass estimation of Oecophylla smaragdina colonies: a model species for the ecological impact of ants. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 8, 464–473. [CrossRef]

- Powell, S., Costa, A. N., Lopes, C. T., & Vasconcelos, H. L. (2011). Canopy connectivity and the availability of diverse nesting resources affect species coexistence in arboreal ants. Journal of Animal Ecology, 80, 352-360. [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A & Ohkawara, K. (2019). Invasive Ants Affect Spatial Distribution Pattern and Diversity of Arboreal Ant Communities in Fruit Plantations, in Tarakan Island, Borneo. Sociobiology, 66(4), 527-535. [CrossRef]

- Robson, S. K., & Traniello, J. F. A. (1999). Key individuals and the organisation of labor in ants. In: Detrain C., Deneubourg J.L., Pasteels J.M. (eds) Information Processing in Social Insects. Birkhäuser, Basel, 239-259.

- Rwegasira, R. G., Mwatawala, M., Rwegasira, G. M., & Offenberg, J. (2015). Occurrence of sexuals of African weaver ant (Oecophylla longinoda Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) under a bimodal rainfall pattern in eastern Tanzania. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 105(2), 182-186. [CrossRef]

- Schlüns, E. A., Wegener, B. J., Schlüns, H., Azuma, N., Robson, S. K. A., & Crozier, R. H. (2009). Breeding system, colony and population structure in the weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina. Molecular Ecology, 18(1), 156-167.

- Trible, W., & Kronauer, D. J. C. (2017). Caste development and evolution in ants: it's all about size. Journal of Experimental Biology, 220(1), 53-62.

- Vanderplank, F. L. (1960). The Bionomics and Ecology of the Red Tree Ant, Oecophylla sp., and its Relationship to the Coconut Bug Pseudotheraptus wayi Brown (Coreidae). Journal of Animal Ecology, 29(1), 15-33. [CrossRef]

- Van Itterbeeck, J., Sivongxay, N., Praxaysombath, B., & van Huis, A. (2014). Indigenous knowledge of the edible weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina Fabricius Hymenoptera: Formicidae from the Vientiane Plain, Lao PDR. Ethnobiology Letters, 5, 4-12. [CrossRef]

- Verghese, A., Jayanthi, P. D. K., Sreedevi, K., Devi, K. S., & Pinto, V. (2013). A quick and non-destructive population estimate for the weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina Fab. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Current Science, 104, 641–646.

- Vidhu, V. V., & Evans, D. A. (2011). Identification of a third worker caste in the colony of Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius) based on morphology and content of total protein, free amino acids, formic acid and related enzymes. Entomon, 36(1/4), 205-212.

- Vidhu, V. V., & Evans, D. A. (2015). Importance of Formic Acid in Various Ethological States of Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius). In: A. K Chakravarthy Ed. New Horizons in Insect Science: Towards Sustainable Pest Management. Part II: Insect Physiology. Springer India, II, 53-60.

- Villalta, I., Oms, C. S., Angulo, E., Molinas-González, C. R., Devers, S., Cerdá, X., & Boulay, R. (2020). Does social thermal regulation constrain individual thermal tolerance in an ant species? Journal of Animal Ecology, 89(9), 2063-2076.

- Wargui, R., Offenberg, J., Sinzogan, A., Adandonon, A., Kossou, D., & Vayssières, J. F. (2015). Comparing different methods to assess weaver ant abundance in plantation trees. Asian Myrmecology, 7, 1–12.

- Wilson, E. O. (1984). The relation between caste ratios and division of labor in the ant genus Pheidole (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 16(1), 89-98. [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Nest 1 | Nest 2 | Pooled Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observations N | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| Sum | 4,541.0000 | 4,563.0000 | 9,104.0000 |

| Mean | 454.1000 | 456.3000 | 455.2000 |

| Sum of squares SS | 2,075,533.0000 | 2,094,329.0000 | 4,169,862.0000 |

| Sample variance S2 | 1,496.1000 | 1,359.1222 | 1,353.7474 |

| Sample std. dev. S | 38.6795 | 36.8663 | 36.7933 |

| std. dev. of mean SE | 12.2315 | 11.6581 | 8.2272 |

| SS | Df | Mean square MS |

F-statistic P value |

| 24.2000 | 1 | 24.2000 | F: 0.0170; P: 0.8979 |

| Nest 1 vs Nest 2 | aTukey HSD Q statistic | Tukey HSD P-value | Tukey HSD inference |

| N = 20 | 0.1841 | 0.8980410 | > 0.05 |

| Scheffé T-statistic | Scheffé p-value | Scheffé inference | |

| Nest 1 – Nest 2 pair | 0.1302 | 0.8978541 | > 0.05 |

| Variables | Nest one | Nest two | Nest three | Total nest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean ±SD | ||||

| Number of leaflets | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8.33 ± 0.5 |

| Nest length | 57.0 | 47.0 | 60.0 | 47.0 | 60.0 | 54.6 ± 11.5a |

| Nest width | 25.0 | 11.0 | 27.0 | 11.0 | 27.0 | 21.0 ± 7.0a |

| Nest height | 15.0 | 9.0 | 20.0 | 2.0 | 23.0 | 14.6 ± 8.5a |

| ***Height from the ground | 6.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 7.33 ± 1.15 |

| Total workers | 14279 | 4985 | 16623 | 4985 | 16623 | 11962 ±6155 |

| Number of major workers Number of intermediate workers** |

5753 4175 |

2009 1458 |

6379 5101 |

2009 1458 |

5753 5101 |

4713 ±2363 3578 ±1893 |

| Number of minor workers | 4351 | 3721 | 5143 | 3721 | 5143 | 1387 ± 1098a |

| Number of winged green queens Number of newly emerged queens* |

17 5 |

15 9 |

19 11 |

15 5 |

19 11 |

17 ± 2 8.33 ±3 |

| Number of drone males : 0 Number of worker pupae |

1255 | 342 | 357 | 15 | 2038 | 878 ± 792a |

| Number of larvae | 854 | 427 | 1375 | 427 | 1375 | 885.3 ±474.7 |

| Egg volume | 3.1 | 4.5 | 15.2 | 3.1 | 15.2 | 7.6 ± 1.6a |

| Queen larvae | 21 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 12 ±10.8 |

| Male larvae | 37 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 22 ±19.4 |

| Eggs count | 1874 | 4890 | 0 | 0 | 4890 | 2254 ±2515 |

| Variables | Colony (3 nests) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean ±SD | |

| Number of leaflets | 6 | 19 | 13.33 ± 4a |

| Nest length | 30.0 | 60.0 | 49.0 ± 12.3a |

| Nest width | 8.0 | 30.0 | 17.0 ± 7.0a |

| Nest height | 2.0 | 23.0 | 10.4 ± 6.7a |

| Nest volume | 829.4 | 16618.5 | 5889.1 ± 6347.9a |

| Height from the ground | 9.0 | 10.0 | 9.6 ± 0.5a |

| Total workers | 2448 | 64761 | 16432 ± 20896a |

| Number of major workers Number of intermediate workers |

1205 201 |

40873 19102 |

15045 ± 19828a 6723.3 ±20170 |

| Number of minor workers | 376 | 4786 | 1387 ± 1098a |

| Number of winged queens* Number of newly emerged queens** Number of males1 |

0 10 0 |

138 33 0 |

64.6 ± 63.9b 21.3 ±11.5 0 |

| Number of worker pupae Queen larvae Male larvae |

154 0 0 |

2038 37 49 |

918 ± 991a 22 ±19.4 29.6 ±26 |

| Number of workers larvae | 71 | 6509 | 2821.6 ± 3319.6a |

| Egg volume Eggs count |

0.0 0 |

4.7 3845 |

1.0 ± 1.6a 1505.6 ± 2053.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).