Submitted:

04 April 2023

Posted:

05 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Methods

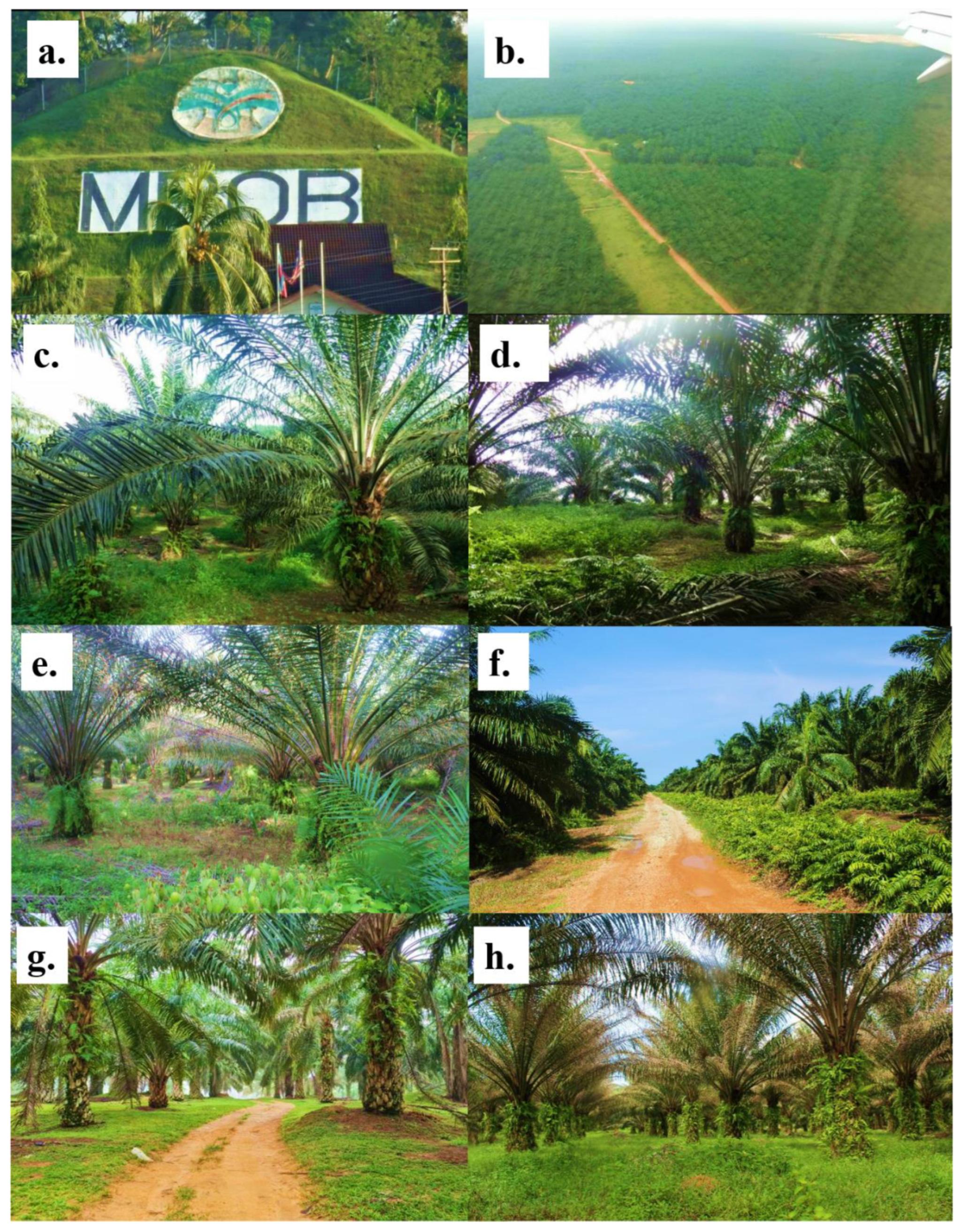

2.1. Study sites

2.2. Surveying the presence-absence of Asian weaver ants in oil palm plantations

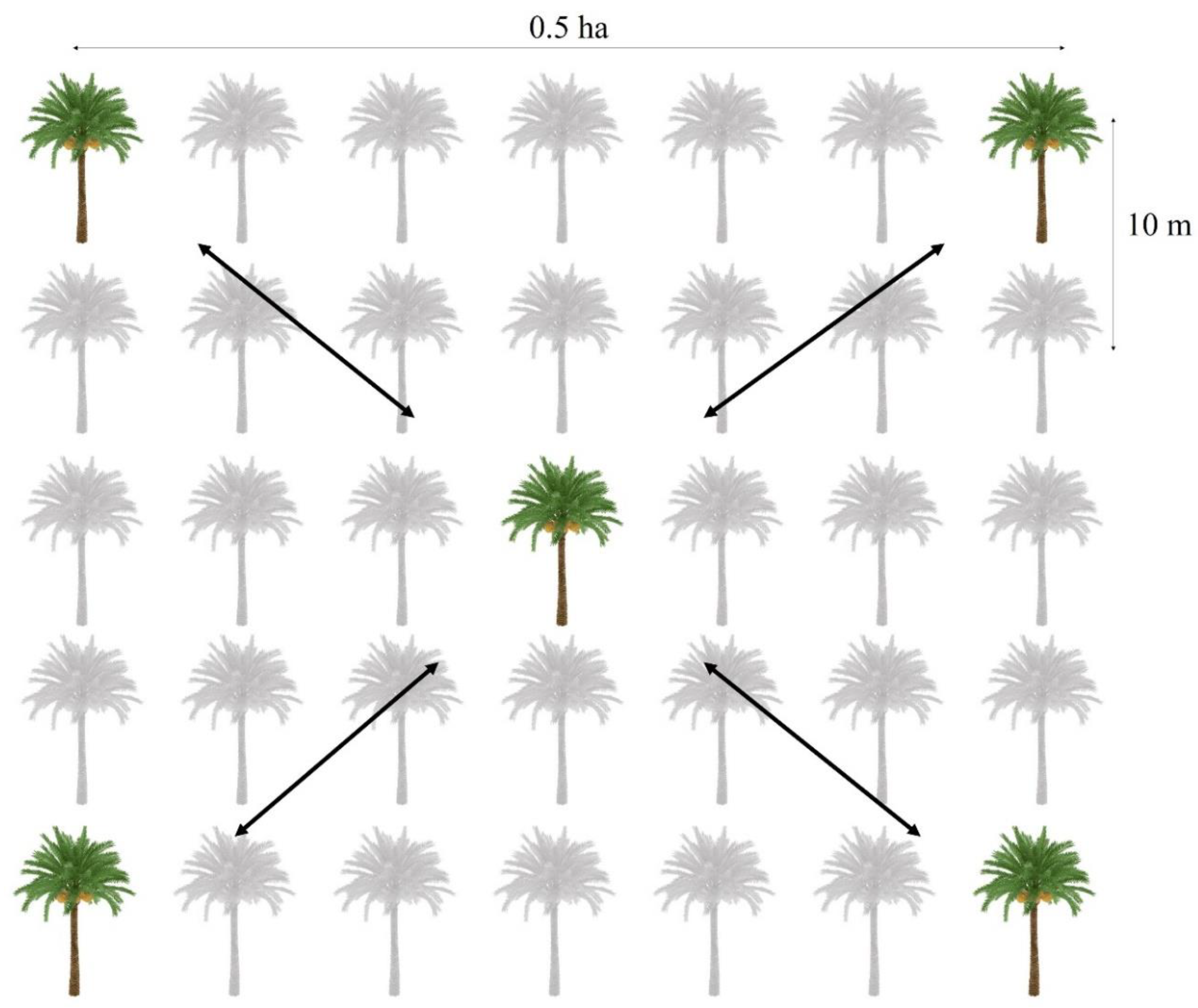

2.3. Nests occupancy patterns in selected plantations

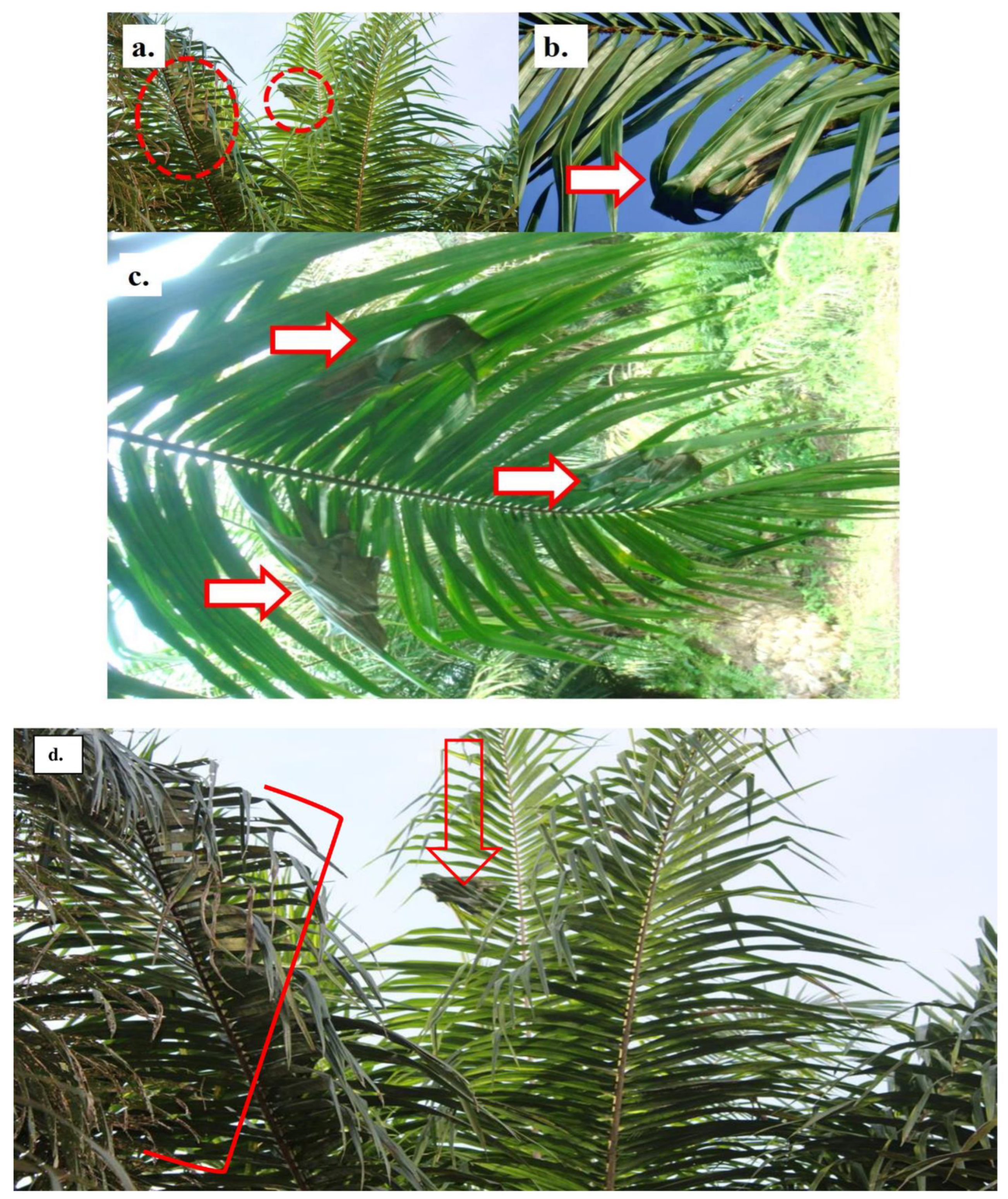

2.4. Brood and barrack nests discrimination

2.5. Nests distribution patterns in relation to maturity status

3. Statistical analysis

3.1. Discriminant analysis

3.2. Colonies age estimation

4. Results

4.1. Spatial distribution of Asian weaver ant colonies

4.2. Colonies nests distribution patterns

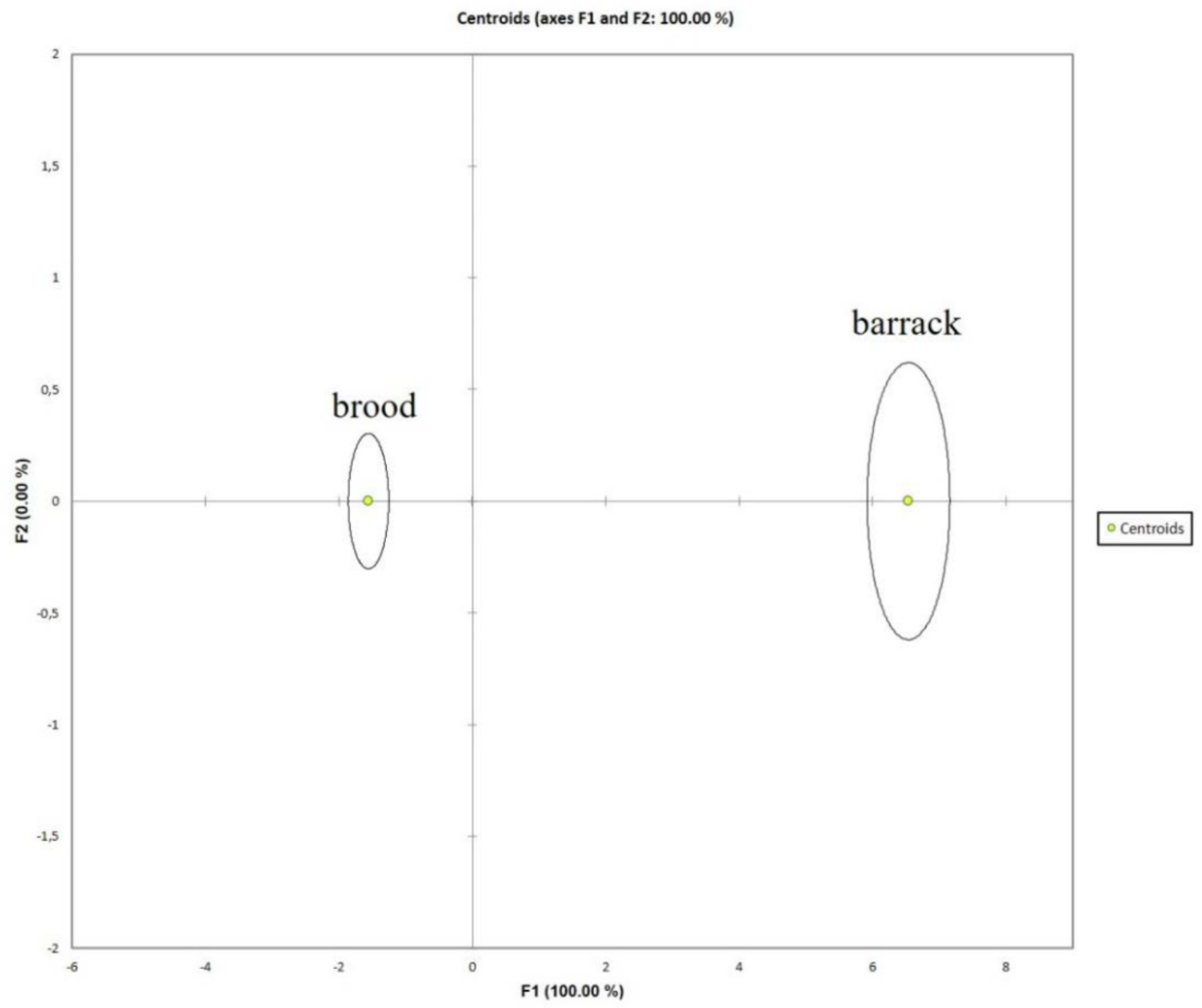

4.3. Discrimination of brood and barrack nests

4.4. Age estimation validation by Pearson correlation coefficient analysis

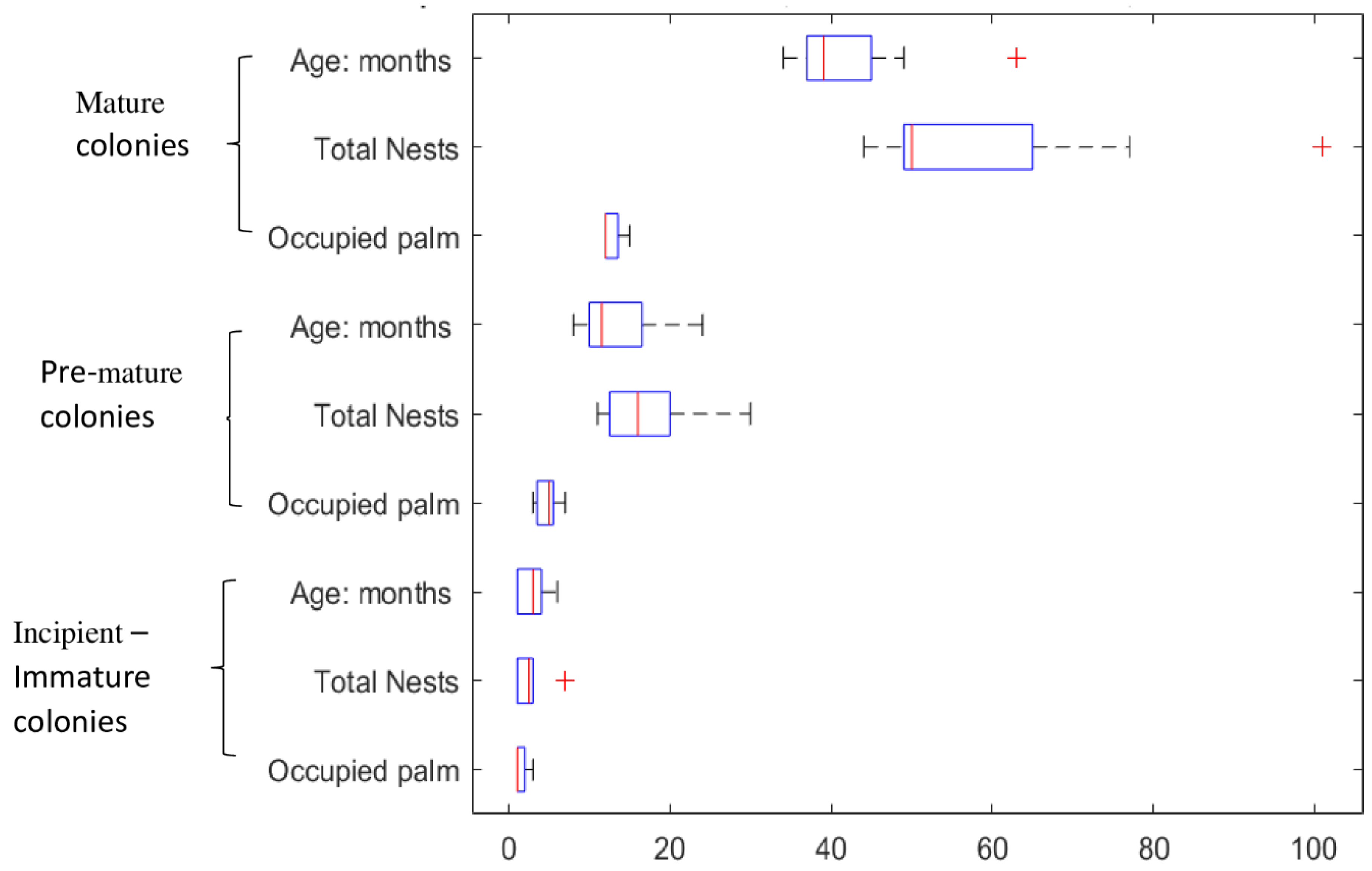

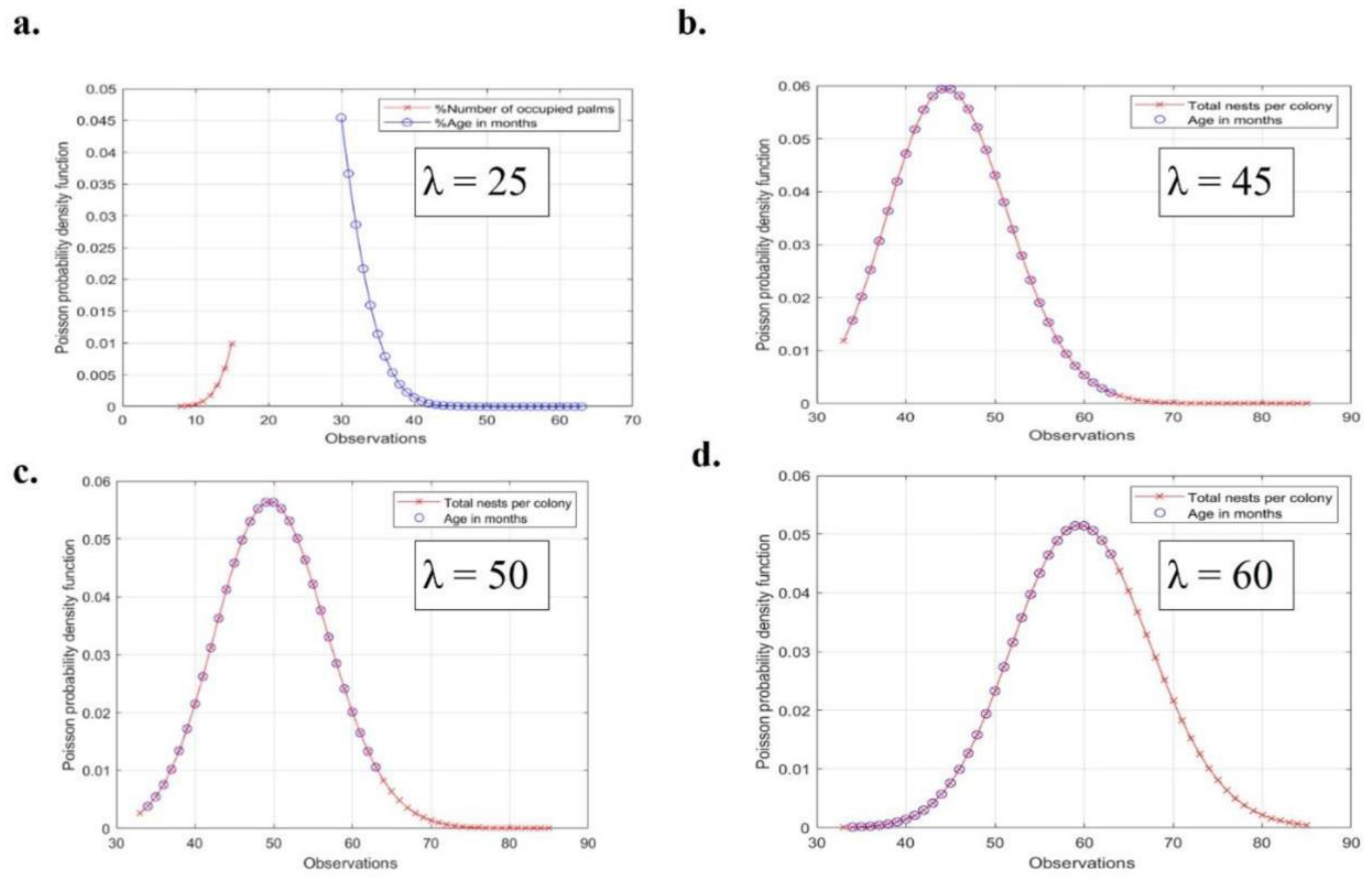

4.5. Colonies age estimation

5. Discussion

5.1. Distribution of Oecophylla smaragdina colonies

5.2. Colonies nests distribution patterns

5.3. Difference between brood and barrack nests

5.4. Average colonies age status of Oecophylla smaragdina

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. The ants. Harvard University Press; 1990.

- Wetterer, JK. Geographic distribution of the weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina. Asian myrmecology. 2017 Jan 1; 9:1-2.

- Peng RK, Christian K. The weaver ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), an effective biological control agent of the red-banded thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in mango crops in the Northern Territory of Australia. International journal of pest management. 2004 Apr 1; 50(2):107-14. [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.K.; Christian, K. Effective control of Jarvis's fruit fly,Bactrocera jarvisi(Diptera: Tephritidae), by the weaver ant,Oecophylla smaragdina(Hymenoptera: Formicidae), in mango orchards in the Northern Territory of Australia. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2006, 52, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.; Rawi, C.S.M.; Ahmad, A.H.; Al-Shami, S.A. Efficacy of Insecticide and Bioinsecticide Ground Sprays to Control Metisa plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in Oil Palm Plantations, Malaysia. . 2015, 26, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamarudin N, Ali SR, Masri MM, Ahmad MN, Manan CA, Kamarudin N. Controlling Metisa plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) outbreak using Bacillus thuringiensis at an oil palm plantation in Slim River, Perak, Malaysia. Journal of Oil Palm Research. 2017 Mar 1; 29(1):47-54. [CrossRef]

- Exélis MP, Idris AH. Studies on the predatory activities of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on Pteroma pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in oil palm plantations in Teluk Intan, Perak (Malaysia). Asian myrmecology. 2013 Jan 1; 5(1):163-76.

- Peng, R.; Christian, K.; Gibb, K. The best time of day to monitor and manipulate weaver ant colonies in biological control. J. Appl. Èntomol. 2011, 136, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng RK, Christian K, Gibb K. Implementing Ant Technology in Commercial Cashew Plantations and Continuation of Transplanted Green Ant Colony Monitoring: A Report for the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. 2004 May; 1-37.

- Binh, NT. (2010). Assessment of an integrated cashew improvement program, using weaver ants as a major component, in cashew production in Vietnam. Charles Darwin University and Institute of Agricultural Science for South Vietnam. 2010 March; (Doctoral Dissertation, Charles Darwin University), 17-135. https://ris.cdu.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/44469117/Thesis_CDU_34457_Nguyen_TB. [CrossRef]

- Exélis, MP. An ecological study of Pteroma pendula (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in oil palm plantations with emphasis on the predatory activities of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on the bagworm/Exelis Moise Pierre. 2015 March; (Msc Dissertation, University of Malaya).

- Dejean A, Corbara B, Orivel J, Leponce M. Rainforest canopy ants: the implications of territoriality and predatory behavior. Functional Ecosystems and Communities. 2007; 1(2):105-20.

- Peng, R.; Christian, K.; Gibb, K. How many queens are there in mature colonies of the green ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius)? Aust. J. Èntomol. 1998, 37, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuisat, M.; Keller, L. Division of labour influences the rate of ageing in weaver ant workers. 269. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, B.H.; Schaible, R. Life Span Evolution in Eusocial Workers—A Theoretical Approach to Understanding the Effects of Extrinsic Mortality in a Hierarchical System. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng RK, Nielsen MG, Offenberg J, Birkmose D. Utilisation of multiple queens and pupae transplantation to boost early colony growth of weaver ants Oecophylla smaragdina. Asian Myrmecology. 2013; 5(1):177-84.

- Blüthgen N, Fiedler K. Interactions between weaver ants Oecophylla smaragdina, homopterans, trees and lianas in an Australian rain forest canopy. Journal of animal ecology. 2002 Sep; 71(5):793-801. [CrossRef]

- Crozier RH, Newey PS, Schluens EA, Robson SK. A masterpiece of evolution–Oecophylla weaver ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News. 2010 May; 13(5):57-71.

- Lim, GT. Enhancing the weaver ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), for biological control of a shoot borer, Hypsipyla robusta (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), in Malaysian mahogany plantations. 2007. (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech).

- Offenberg, J.; Peng, R.; Nielsen, M.G. Development rate and brood production in haplo- and pleometrotic colonies of Oecophylla smaragdina. Insectes Sociaux 2012, 59, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, C.; Andersen, A.N. Cooperation Between Dealate Queens During Colony Foundation in the Green Tree Ant, Oecophylla Smaragdina. Psyche: A J. Èntomol. 1989, 96, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissing, S.W.; Pollock, G.B. An experimental analysis of pleometrotic advantage in the desert seed-harvester antMessor pergandei (Hymenoptera; Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux 1991, 38, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, K.; Hölldobler, B. Colony founding by queen association and determinants of reduction in queen number in the antLasius niger. Anim. Behav. 1995, 50, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronauer, D.J.C.; Miller, D.J.; Hölldobler, B. Genetic evidence for intra– and interspecific slavery in honey ants (genusMyrmecocystus). 270. [CrossRef]

- Tschinkel, W.R. Brood raiding and the population dynamics of founding and incipient colonies of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Ecol. Èntomol. 1992, 17, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood BJ, Kamarudin N. A review of developments in integrated pest management (IPM) of bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) infestation in oil palms in Malaysia. Journal of Oil Palm Research. 2019 Dec 10; 31(4):529-39.

- Wood BJ, Kamarudin N. Bagworm (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) Infestation in the centennial of the Malaysian oil palm industry—A review of causes and control. Journal of Oil Palm Research. 2019 Sep 1; 31(3):364-80. [CrossRef]

- Exélis, M.P.; Ramli, R.; Ibrahim, R.W.; Idris, A.H. Foraging Behaviour and Population Dynamics of Asian Weaver Ants: Assessing Its Potential as Biological Control Agent of the Invasive Bagworms Metisa plana (Lepidoptera: Psychidae) in Oil Palm Plantations. Sustainability 2022, 15, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Ishak, M.Y.; Makmom, A.A. Nexus between climate change and oil palm production in Malaysia: a review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokkers, C. Colony dynamics of the green tree ant (Oecophylla smaragdina Fab.) in a seasonal tropical climate. 1990. (Doctoral dissertation, James Cook University).

- Van Mele P, Cuc NT. Evolution and status of Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius) as a pest control agent in citrus in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. International Journal of Pest Management. 2000 Jan 1; 46(4):295-301. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, N. Seasonal pattern in the territorial dynamics of the arboreal ant Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal-Bombay Natural History Society. 2007 Jan; 104(1):30.

- Jander, R.; Jander, U. The Light and Magnetic Compass of the Weaver Ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ethology 1998, 104, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, M.S.; Azid, A.; Khalit, S.I.; Sani, M.S.A.; Lananan, F. Comparison of prediction model using spatial discriminant analysis for marine water quality index in mangrove estuarine zones. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsudin, M.S.; Azid, A.; Khalit, S.I.; Sani, M.S.A.; Lananan, F. Comparison of prediction model using spatial discriminant analysis for marine water quality index in mangrove estuarine zones. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrea RS, Morgan BJ. Analysis of capture-recapture data. CRC Press; 2014 Aug 1.

- Mukaka, M.M. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. . 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish journal of emergency medicine. 2018 Sep 1; 18(3):91-3. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig JA, Reynolds JF. Statistical ecology: a primer in methods and computing. John Wiley & Sons; 1988. 18 May.

- Gowda, D.M. PROBABILITY MODELS TO STUDY THE SPATIAL PATTERN, ABUNDANCE AND DIVERSITY OF TREE SPECIES. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimid M, Hassan A, Tahir NA, Thevan K. Colony structure of the weaver ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Fabricius)(Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Sociobiology. 2012; 59(1):1-0. [CrossRef]

- MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox. The Mathworks Inc. Natick, Massachusetts, USA. 2021.

- Blüthgen, N.; Stork, N.E. Ant mosaics in a tropical rainforest in Australia and elsewhere: A critical review. Austral Ecol. 2007, 32, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.W.; Lessard, J.; Bernau, C.R.; Cook, S.C. The Tropical Ant Mosaic in a Primary Bornean Rain Forest. Biotropica 2007, 39, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Tuck, H.C.; Lay, T.C. Exploring arboreal ant community composition and co-occurrence patterns in plantations of oil palm Elaeis guineensis in Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia. Ecography 2008, 31, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim NR, Wan Jusoh WFA, Mohd Nasir MNS. Short Communication. Ant diversity in a Peninsular Malaysian mangrove forest and oil palm plantation. Asian Myrmecology. 2010; Volume 3, 5–8.

- Van Wijngaarden PM, Van Kessel M, Van Huis A. Oecophylla longinoda (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as a biological control agent for cocoa capsids (Hemiptera: Miridae). In Proceedings of the Netherlands Entomological Society Meeting. 2007; (Vol. 18, 21-30).

- Nene, WA. Aspects of ecology of weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Tanzania. 2016, (. Doctoral Dissertation, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro.

- Wargui R, Offenberg J, Sinzogan A, Adandonon A, Kossou D, Vayssières JF. Comparing different methods to assess weaver ant abundance in plantation trees. Asian Myrmecology. 2015; 7, 159-170.

- Dejean, A.; Djieto-Lordon, C.; Durand, J.L. Ant Mosaic in Oil Palm Plantations of the Southwest Province of Cameroon: Impact on Leaf Miner Beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Èntomol. 1997, 90, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Izwan A, Amiruddin BA. Diversity of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at Kuala Lompat, Krau Wildlife Reserve, Pahang, Malaysia. The Journal of Wildlife and Parks. 2014; 28, 31-39.

- Vayssières, J.; Grechi, I.; Sinzogan, A.; Ouagoussounon, I.; Todjihoundé, R.; Modjibou, S.; Tossou, J.; Adandonon, A.; Kikissagbé, C.; Tamò, M.; et al. Host plants and associated trophobionts of the weaver ant Oecophylla longinoda Latreille (Hymenoptera Formicidae) in Benin. Agric. For. Èntomol. 2021, 24, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, K.; Maschwitz, U. The symbiosis between the weaver ant,Oecophylla smaragdina, andAnthene emolus, an obligate myrmecophilous lycaenid butterfly. J. Nat. Hist. 1989, 23, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Christian, K. Integrated pest management in mango orchards in the Northern Territory Australia, using the weaver ant,Oecophylla smaragdina, (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) as a key element. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2005, 51, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, M.; Bolton, B. Competition between ants for coconut palm nesting sites. J. Nat. Hist. 1997, 31, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B. Territories of the African Weaver Ant (Oecophylla longinoda [Latreille]); A Field Study. 51. [CrossRef]

- Offenberg, J. The use of artificial nests by weaver ants: A preliminary field observation. Asian Myrmecology. 2014 Jan 1; 6(1):6.

- Schlüns EA, Wegener BJ, Schlüns H, Azuma N, Robson SK, Crozier RH. Breeding system, colony and population structure in the weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina. Molecular Ecology. 2009 Jan; 18(1):156-67.

- Exélis, MP, Ramli R, Idris AH, Latif SA, Yaakop S, Ibrahim RW. Relationships between weather parameters and foraging daily activity of Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in oil palm plantations: Case Study. 14 November. [CrossRef]

- Van Mele, P.; Cuc, N.T.T.; VanHuis, A. Direct and indirect influences of the weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina on citrus farmers' pest perceptions and management practices in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2002, 48, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, M.J.; Khoo, K.C. Role of Ants in Pest Management. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 1992, 37, 479–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthicharoencha D, Chantarasawat N. Ant species diversity in the establishing area for advanced technology institute at Lai-Nan sub-district, Wiang Sa district, Nan province, Thailand. Tropical Natural History. 2006 Oct 1; 6(2):67-74.

- Olotu, MI. Effect of seasonality on abundance of African weaver ant Oecophylla longinoda (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in cashew agro-ecosystems in Tanzania. African Journal of Agricultural Research. 2016 Apr 21; 11(16):1439-44. [CrossRef]

- Rwegasira RG, Mwatawala MW, Rwegasira GM. Seasonal population structure of African weaver ants Oecophylla longinoda (Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) under bimodal rainfall pattern in Tanzania. Methods for Enhancing Weaver Ant (Oecophylla Longinoda latreille) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Populations for Sustainable Control of Insect Pests of Crops. Doctoral Dissertation, Sokoine University of Agriculture. MOROGORO, TANZANIA. 2016; 74-88.

- Ribeiro S, Espirito Santo N, Delabie J, Majer J. Competition, resources and the ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) mosaic: a comparison of upper and lower canopy. Mycological Progress. 2013; 18:113-20.

- Pfeiffer, M.; Tuck, H.C.; Lay, T.C. Exploring arboreal ant community composition and co-occurrence patterns in plantations of oil palm Elaeis guineensis in Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia. Ecography 2008, 31, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holldobler, B. Territorial Behavior in the Green Tree Ant (Oecophylla smaragdina). Biotropica 1983, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exélis, MP, Ramli R. A Review on Distribution Pattern, Nesting Style, Mating Behavior, Colony Organization of Asian weaver ant Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Occupying Strategic Biome-agroforestry Systems of Asia. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bigger, M. Observations on the insect fauna of shaded and unshaded Amelonado cocoa. Bull. Èntomol. Res. 1981, 71, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, S.M.; Ittonen, M.; Seppä, P.; Helanterä, H. Limited dispersal and an unexpected aggression pattern in a native supercolonial ant. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 3671–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, M.M.; Guo, X.; Wong, T.; Malaekeh, A.; Harrison, J.F.; Fewell, J.H. Cooperation among unrelated ant queens provides persistent growth and survival benefits during colony ontogeny. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangma JS, Prasad SB. Population and Nesting Behaviour of Weaver Ants, Oecophylla smaragdina from Meghalaya, India. Sociobiology. 2021 Dec 23; 68(4):e7204-. [CrossRef]

- Offenberg J, Cuc NT, Wiwatwitaya D. The effectiveness of weaver ant (Oecophylla smaragdina) biocontrol in Southeast Asian citrus and mango. Asian Myrmecology. 2013 Jan 1; 5(1):139-49.

- Peng, R.; Christian, K.; Gibb, K. Locating queen ant nests in the green ant, Oecophylla smaragdina (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux 1998, 45, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Itterbeeck, J.; Sivongxay, N.; Praxaysombath, B.; Van Huis, A. Indigenous Knowledge of the Edible Weaver Ant Oecophylla smaragdina Fabricius Hymenoptera: Formicidae from the Vientiane Plain, Lao PDR. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2014, 5, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Itterbeeck, J.; Sivongxay, N.; Praxaysombath, B.; van Huis, A. Location and external characteristics of the Oecophylla smaragdina queen nest. Insectes Sociaux 2015, 62, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwegasira, R.G.; Mwatawala, M.; Rwegasira, G.M.; Mogens, G.N.; Offenberg, J. Comparing different methods for trapping mated queens of weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda; Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderplank, F.L. The Bionomics and Ecology of the Red Tree Ant, Oecophylla sp., and its Relationship to the Coconut Bug Pseudotheraptus wayi Brown (Coreidae). J. Anim. Ecol. 1960, 29, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayle, T.M.; Turner, E.C.; Snaddon, J.L.; Chey, V.K.; Chung, A.Y.; Eggleton, P.; Foster, W.A. Oil palm expansion into rain forest greatly reduces ant biodiversity in canopy, epiphytes and leaf-litter. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2010, 11, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, D.A. Designing agricultural landscapes for biodiversity-based ecosystem services. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2017, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pag-Ong, AI. Taxonomy and diversity of ants associated with cacao and evaluation of Oecophylla smaragdina Fabricius (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) for biological control of Helopeltis bakeri Poppius (Hemiptera: Miridae) in Quezon and Laguna, Philippines. 2021. Doctorate dissertation, De La Salle University, Manila Philippines.

- Eilenberg, J. Concepts and visions of biological control. In: Eilenberg J, Hokkanen H. (eds). An ecological and societal approach to biological control. Springer, Dordrecht. 2006:1-1.

- Gonzálvez, F.G.; Santamaría, L.; Corlett, R.T.; Rodríguez-Gironés, M.A. Flowers attract weaver ants that deter less effective pollinators. J. Ecol. 2012, 101, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Gonzálvez FG, Llandres AL, Corlett RT, Santamaría L. Possible role of weaver ants, Oecophylla smaragdina, in shaping plant–pollinator interactions in South-East Asia. Journal of Ecology. 2013 Jul; 101(4):1000-6. [CrossRef]

| Plantations | Number of colonies | Total Number of nests** | Average Number of nests/ colony | Range of occupied palms/colony | Total Number of occupied palms/total sampling | Average number of palm/ colony | Estimated range of occupied land surface/colony m2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM Jr* | 27 | 1105 | 40.92 | 8-21 | 320 | 11.85 | 800-2100 |

| Felcra Jr | 20 | 1109 | 55.45 | 10-12 | 200 | 10 | 1000 |

| Boustead Jr | 16 | 832 | 52 | 10-15 | 197 | 12.3 | 1000-1500 |

| MPOB Pr* | 27 | 1216 | 45 | 7-15 | 351 | 13 | 700-1500 |

| MPOB Sb | 20 | 1083 | 54.15 | 12 | 240 | 12 | 1200 |

| MPOB Sr | 16 | 1598 | 99.8 | 12-25 | 219 | 13.6 | 1200-2500 |

| Felda Pr | 10 | 390 | 39 | 7-8 | 72 | 7.2 | 700-800 |

| Total | 136 | 7333 | 386.32 | 7-25 | 1599 | 80 | 4 x 106*** |

| Mean | 19.4 | 1047.5 | 55.2 | 7-25 | 228.42 | 11.42 | 1342.85 |

| Contrast | Difference | Standardized difference | Critical value | Pr > Diff | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| brood vs barrack | 3.9524 | 9.4998 | 2.0086 | < 0.0001 | Yes |

| Tukey's d critical value: | 2.8405 | ||||

| Category | LS means | Standard error | Lower bound (95%) | Upper bound (95%) | Groups |

| brood | 7.9524 | 0.1824 | 7.5859 | 8.3188 | A |

| barrack | 4.0000 | 0.3739 | 3.2490 | 4.7510 | B |

| Category* | LS means(Var1) | Groups | |||

| brood | 7.9524 | A | |||

| barrack | 4.0000 | B | |||

| Model type | Significant variables ranking | Dataset | Correct classification, % | Number of nest and p-values of Fisher distance1,2 | Total nest | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable, F-statistics and p-value | Variable and VIP value | Brood | Barrack | ||||

| Discriminant analysis | Number of minor workers (F-statistics: 127.6578, p-value: < 0.0001); Height from the ground (F-statistics: 90.2458, p-value: < 0.0001); Number of worker pupae (F-statistics: 39.5015, p-value: < 0.0001); Number of larvae (F-statistics: 38.3714, p-value: < 0.0001); Number of total workers (F-statistics: 21.0614, p-value: < 0.0001); Number of leaflets (F-statistics: 9.6910, p-value: < 0.0031); and Number of winged queen (F-statistics: 5.1609, p-value: < 0.0274) |

Not related | Training dataset | ||||

| Brood | 100.00 | 18 (1) | 0 (< 0.0001) | 18 | |||

| Barrack | 100.00 | 0 (< 0.0001) | 10 (1) | 8 | |||

| Total | 100.00 | 26 | |||||

| Validation dataset | |||||||

| Brood | 100.00 | 18 (1) | 0 (< 0.0001) | 18 | |||

| Barrack | 100.00 | 0 (< 0.0001) | 10 (1) | 8 | |||

| Total | 100.00 | 26 | |||||

| Partial least square -discriminant analysis | Not related | Number of minor workers (VIP: 1.7272); Height from the ground (VIP: 1.6345); Number of worker pupae (VIP: 1.3537); Number of larvae (VIP: 1.3427); Number of total workers (VIP: 1.1093); Number of major workers (VIP: 0.9928); and Number of leaflets (VIP: 0.8210) |

Training dataset | ||||

| Brood | 95.24 | 16 (1) | 2 (< 0.0001) | 18 | |||

| Barrack | 100.00 | 0 (< 0.0001) | 10 (1) | 8 | |||

| Total | 96.15 | 26 | |||||

| Validation dataset | |||||||

| Brood | 95.24 | 16 (1) | 2 (< 0.0001) | 18 | |||

| Barrack | 100.00 | 0 (< 0.0001) | 10 (1) | 8 | |||

| Total | 96.15 | 26 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).