1. Introduction

Ultra-deep geological conditions are complex, with extensive multi-scale fractures and cavities, creating harsh engineering environments prone to severe lost circulation and large and medium leaks [

1,

2]. Managing such leaks is challenging, with significant drilling fluid loss. Unlike small leaks, severe lost circulation often halts drilling operations and causes sudden wellbore pressure drops [

3]. This significantly impacts drilling safety and cost reduction. For example, the Jialingjiang Formation in western Chongqing’s shale gas block has well-developed fractures and cavities, with frequent severe lost circulation during the third drilling phase. In this area, 50.4% of Jialingjiang Formation wells experience complex lost circulation, averaging 5,152.46 m

3 lost per well and 80.99-day treatment cycles [

4]. In the Middle East, over 30% of wells drilling carbonate fracture reservoirs experience severe wellbore leaks, with over 50% of lost time attributed to such leaks [

5]. Severe Lost Circulation, with sudden onset and unpredictability, renders conventional plugging methods ineffective. Efficient, reliable plugging materials and techniques are lacking. Single-time plugging success rates are generally low. For example, single-time plugging success rates are below 10% in western Chongqing’s Erkaifault and below 25% in Xinjiang’s Shunbei Block [

6]. In Saudi Arabia’s Ghawar Oilfield’s fractured Permian Khuff Formation, single-time plugging success rates are below 20%[

7,

8].

Low plugging success rates stem mainly from severe lost circulation (loss rate >50 m

3/h). In such formations, lost circulation channels are wide and irregular [

9]. In field drilling, the bridging method is widely used for its simplicity and low cost [

10]. However, in large lost circulation channels, bridging agent particles and fibers often fail to effectively retain, bridge, and seal, causing plugging failures. Thus, chemical plugging has emerged as a key supplement for severe lost circulation [

11,

12]. Chemical gels are fluid prior to cross-linking, enabling penetration of diverse lost circulation channels. After solidification, a dense, high-strength plug is formed, suitable for sealing complex, irregular fractures [

13,

14]. For example, Ying-Rui Bai synthesized a gel with favorable strength, flexibility, and oil absorption for controlling circulation loss in fractured formations [

15]; Guancheng Jiang developed a high-temperature, high-strength cross-linked polymer gel (GelHTCMG) with 9.8 MPa pressure-bearing capacity at 150°C, sealing 3 mm slots [

16]; Binqiang Xie et al. developed a novel HMP-Gel (hydrophobically modified polyacrylamide and polyethyleneimine) with excellent sealing in high-permeability carbonates and 1–3 mm fractures [

17]; Dao et al. proposed a resorcinol-hexamethylenetetramine gel for ultra-high-temperature reservoir water control; however, its excessively short gelation time and high strength at extreme temperatures hinder meeting fractured formation sealing requirements, limiting its use [

18].

Thus, despite gel materials being applied in severe lost circulation scenarios with some success, their plugging performance still has significant shortcomings, hindering widespread adoption. On one hand, gel rheological properties are highly sensitive to environmental conditions, easily influenced by temperature and formation water salinity, resulting in premature gelation and failed leak sealing [

19,

20]. On the other hand, gels have limited pressure-bearing capacity, ineffective for large-scale lost circulation channels. Additionally, good flowability aids entry into lost circulation channels but increases difficulty in controlling gel retention and gelation time [

21].

To address the limitations of chemical gels in severe lost circulation control, various plugging technologies are reviewed, and bridging plugging materials are introduced for use in combination with chemical gels to explore their application potential in severe lost circulation formations. This method combines the excellent adaptability of gels to different channel morphologies with the tendency of bridging particles to retain in channels, with the aim of achieving a synergistic plugging effect. Additionally, to address the inherent performance limitations of gels, focus is placed on two aspects: selecting crosslinking agents, introducing functional fillers to enhance structural strength and gel control capabilities, and optimizing gelation time control strategies. This innovative gel-bridging coupled plugging system combination is promising for providing more efficient and feasible technical solutions for on-site management of severe lost circulation formations.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials and Instruments

The polymer gel agent used in this experiment is water-soluble polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, medium polymerization degree, molecular weight 120,000–150,000), supplied by Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., to balance the appropriate solution viscosity and post-gelation mechanical strength. Crosslinking agents include 2 wt% glutaraldehyde, 1 wt% borax (sodium tetraborate), and 1 wt% sodium tripolyphosphate, all purchased from Shandong Longhui Chemical Co., Ltd. Filler materials are 1 wt% starch, 1 wt% montmorillonite, and 1 wt% hydrophilic nanosilica, all supplied by Jingzhou Jiahua Technology Co., Ltd. The water-based drilling fluid used is the potassium-based polyacrylamide system commonly used in the Tarim Oilfield, Xinjiang, with a density of 1.50 g/cm3.

During the experiment, gel stirring was conducted using a JJ-1 timer-controlled electric stirrer (Shanghai Puchun Metrology Instrument Co., Ltd.); temperature control was achieved using an HH series digital display constant temperature water bath (Changzhou Guoyu Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd.). Gel mechanical properties were tested using an MD-NJ5 gel strength tester (Linan Fengyuan Electronics Co., Ltd.) and a DFC-0712B dual-cylinder pressure thickening tester (Shenyang Jinouke Petroleum Instrument Technology Development Co., Ltd.). Rheological parameters were measured using an LVDV-11+P Brookfield viscometer (Jingzhou Jiahua Technology Co., Ltd.). Gel properties under thermal aging conditions were evaluated using the XGRL-4A high-temperature roller heating furnace (Qingdao Chuangmeng Instrument Co., Ltd.). Fracture simulation plugging tests were conducted using the simulated natural fracture plugging instrument manufactured by Jingzhou Talin Mechanical and Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Co., Ltd.

2.2. Preparation of Particle-Reinforced Gel

In recent years, acrylamide copolymer crosslinked gels have seen widespread use in oilfield plugging. However, their amide groups hydrolyze at high temperatures, converting to carboxylic acids, causing polymer particles to harden continuously and lose plasticity. In contrast, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a non-ionic polymer, resists high-temperature hydrolysis, preventing hardening failure. Its low toxicity, water dilution resistance, and excellent water resistance enable slight gel swelling after prolonged water immersion, enhancing plugging effectiveness. Additionally, gel-rock pore wall bonding strength is significantly enhanced post-gelation. Based on these advantages, water-soluble PVA (120,000–150,000 molecular weight) was selected as the main agent, with a particle-reinforced gel prepared via the following steps: first, PVA was placed in an 80 °C water bath and stirred to full dissolution; simultaneously, 1 wt% starch, montmorillonite, or hydrophilic nanosilica particles were physically stirred for 4 h and ultrasonically dispersed for 1 h to obtain a uniformly dispersed filler suspension; this suspension was slowly added to the PVA solution and stirred at 80 °C for full filler dispersion; Finally, a crosslinking agent (e.g., glutaraldehyde, borax, sodium tripolyphosphate) was added at the pre-selected ratio and pre-cured in an 80 °C water bath for 1–2 h to adjust viscosity and ensure pumpability. Subsequently, samples were transferred to a high-temperature roller heating furnace for 80 °C thermal aging (8 h), completing final curing to produce high-strength, gelation time-controlled particle-reinforced PVA gel.

2.3. Gel Properties Evaluation Method

2.3.1. Gel Properties Evaluation Method

The gelation time of the gel at 80 °C was determined using the DFC-0712B dual-cylinder pressure thickener. The sample was placed into the thickener cylinder, rotor speed was set in accordance with ASTM D737-18 standards, the time required for viscosity to transition from low (pumpable state) to high (gel state) was recorded, and the average of three tests was taken as the gelation time.

2.3.2. Gel Strength Test

The maximum force required for the probe to penetrate the gelled sample at a constant speed (1 mm/s) was measured using the MD-NJ5 Gel Strength Tester. Each group of samples was tested after being allowed to stand at room temperature for 24 hours, with the test repeated five times. The average value and standard deviation were then calculated to evaluate the gel’s puncture resistance and toughness.

2.3.3. Rheological Characterization

Viscosity changes of the gel in each base formulation at 25 °C under different shear rates (17–1021 s-1) were measured using the LVDV-11+P Brookfield viscometer. Viscosity-shear rate curves were analyzed to determine the gel’s pseudoplastic or Bingham plastic characteristics, thereby revealing its rheological behavior during wellbore pumping and within lost circulation channels.

2.3.4. Thermal Stability Evaluation

Gel samples from each base formulation were cut into cylinders (25 mm diameter × 20 mm height), and their initial gel strength was first determined; they were then placed in an XGRL-4A high-temperature roller heating furnace and subjected to rolling aging at temperatures ranging from 80 °C to 120 °C (with one experimental set conducted every 5 °C) for 4 hours. After removal, gel strength was measured again and compared with the initial value to evaluate mechanical stability under high-temperature conditions. Subsequently, the removed samples were aged at 120°C for 60 hours, with the current-to-original volume ratio recorded every 5 hours to assess the thermal stability of gels from each base formulation under long-term high-temperature conditions.

2.3.5. Temperature Sensitivity Analysis

Viscosity changes of the optimized gel system at different temperatures were tested using a Brookfield viscometer at a constant shear rate of 17 s-1. The total test duration was 250 minutes, with temperatures ranging from 20°C to 140°C. Measurements were taken every 10 minutes, and data points with significant changes were selected to plot the resulting curve. This was performed to simulate and evaluate whether the optimized gel system could maintain a low-viscosity, fast-flowing state prior to being pumped into the target layer.

2.3.6. Contamination Resistance Testing

To simulate the effects of on-site mud contamination on the optimized gel system, water-based drilling fluids with 5 wt%, 10 wt%, 15 wt%, and 20 wt% (mass fraction) concentrations were mixed with the ungelified PVA–filler–crosslinker system at a 1:1 volume ratio. After thorough mixing, the gelation time of the contaminated gel and its strength 24 hours post-gelation were measured at 80 °C to assess the inhibitory effect of drilling fluid components on gelation behavior.

2.3.7. Microstructural Analysis

The morphology of gel systems without nanomaterials and those with nanomaterials was observed and compared using a scanning electron microscope (field emission type, Hitachi SU8010) after gelation at 80°C and 24-hour aging. Prior to testing, gel samples were freeze-dried for 24 hours to remove moisture and sputter-coated with gold to enhance conductivity. The microscopic pore structure, network crosslinking morphology, and filler distribution were observed, and the effects of nanomaterials on the gel’s microstructural density and pore uniformity were analyzed.

2.3.8. Selection of Optimal Bridging Particles

The candidate bridging agent (particles) at a concentration of 1 wt% was added to the PVA solution. Stirring was performed using a JJ-1 timer-controlled electric stirrer at 500 rpm for 15 minutes. The mixture was then allowed to stand, and settling time and dispersion uniformity were observed at 25 °C. Based on particle suspension duration and final settling rate, the solid-phase material most suitable for synergistic suspension and bridging with the gel system was selected.

2.3.9. Simulated Natural Fracture Plugging Experiment

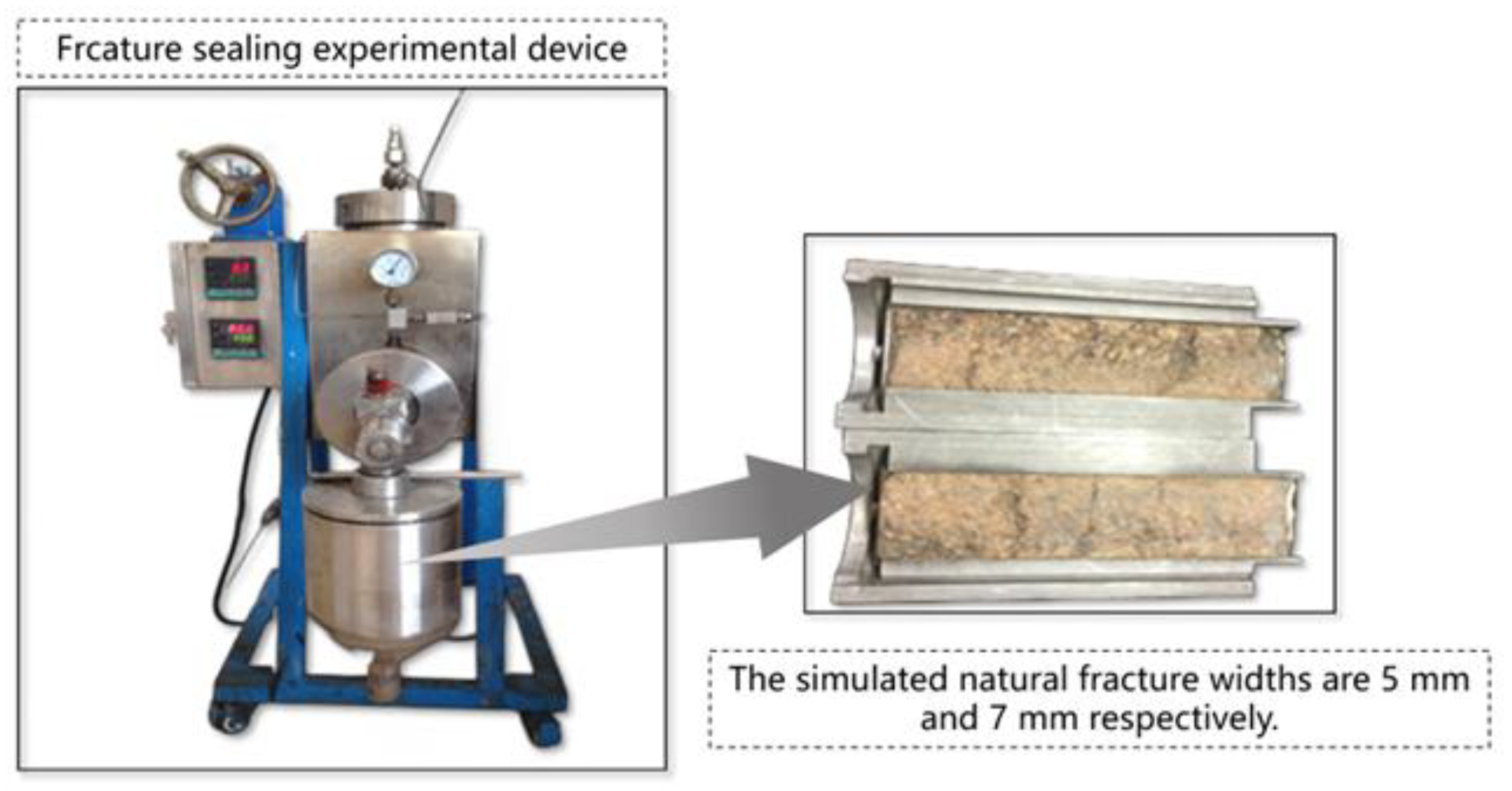

As shown in

Figure 1, a natural fracture high-temperature and high-pressure loss evaluation device manufactured by Jingzhou Taling was utilized, equipped with a natural sandstone flat fracture module (7 mm width) to simulate a severe lost circulation formation environment. Under conditions of 120 °C, 5 MPa pore pressure, and 10 MPa downhole pressure, pre-prepared gel–bridge coupled plugging fluid was injected, with leakage rates recorded over time. Sealing efficiency and stability time were compared among single-use bridge particles, single-use gel, and composite systems to quantitatively assess the field application potential of coupled plugging technology.

3. Mechanism of Action

In complex lost circulation formations, conventional chemical gels, due to their low initial viscosity, tend to flow rapidly upon entering high-permeability or fractured channels, making effective sealing difficult. Particularly in high-temperature environments, conventional gels have limited pressure-bearing capacity, rendering them prone to being squeezed into deeper channels or expelled, thus impairing the plugging effect. To address this, nanoparticles are introduced in this paper to overcome the issues of insufficient strength and poor temperature resistance in conventional gels, and a bridging agent is combined with the gel to compensate for the deficiencies of single materials in complex lost circulation channels, such as poor retention and weak pressure-bearing capacity. Through the synergistic action of multiple mechanisms, excellent plugging performance is achieved by the two [

22].

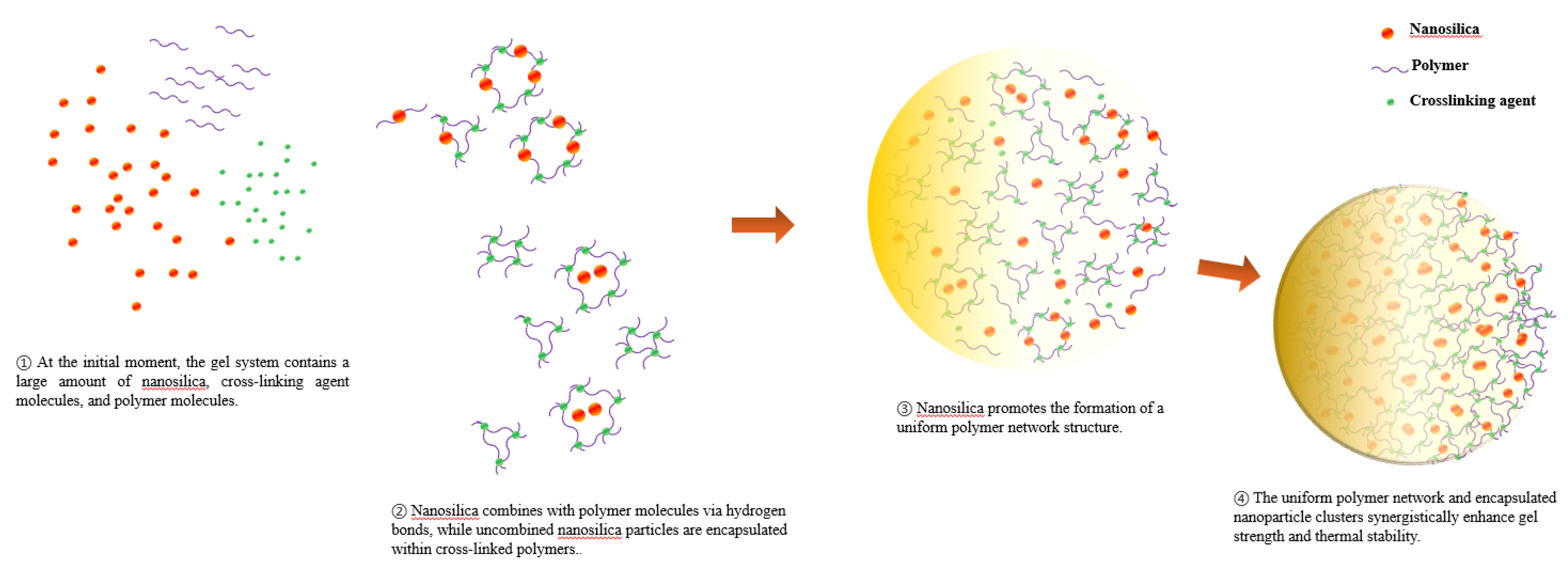

(1) Mechanism of action of nanomaterials in enhancing gel properties

The mechanism by which nanosilica enhances the mechanical properties and temperature resistance stability of the gel is illustrated in

Figure 2. Nanosilica dispersed within the gel system can interact with polymer molecules via hydrogen bonding, thereby inhibiting their degradation at high temperatures [

23]. Furthermore, due to the hydrophilic nature of hydroxyl groups on the surface of nanoparticles, the dehydration of the gel at high temperatures can be delayed, allowing the gel system to retain more moisture to resist high-temperature effects. Meanwhile, the combination of nanosilica with polymer molecules improves the originally disordered distribution of polymer molecules within the gel system, forming a more uniform polymer network and significantly enhancing gel strength. In addition, during the crosslinking process, some nanosilica forms aggregates that fill the pores of the network structure, increasing its compactness and thereby further enhancing the strength of the network structure [

24].

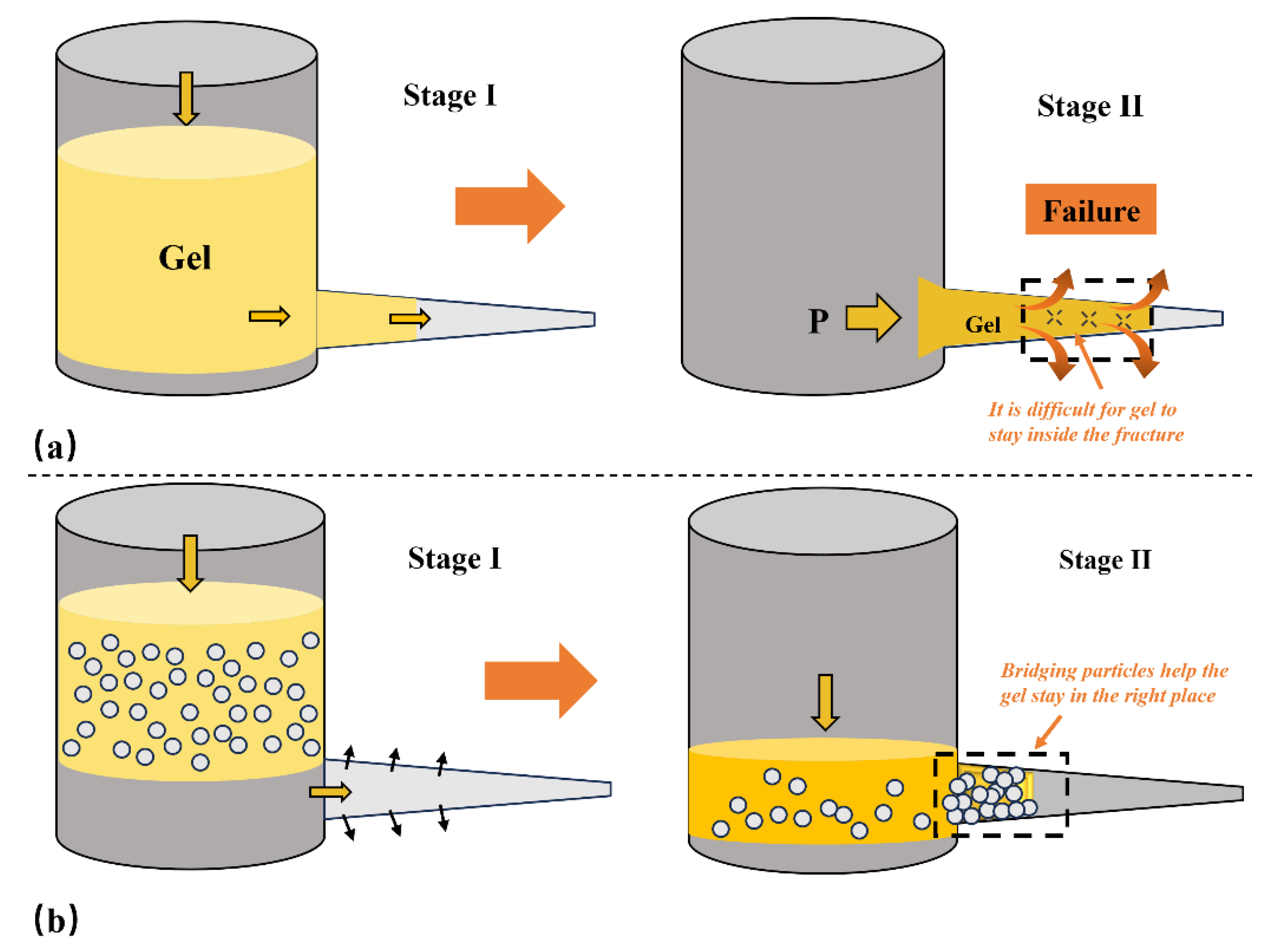

(2) Gel - Synergistic mechanism of coupled plugging

Figure 3(a) illustrates that conventional chemical gels, due to their low initial viscosity, flow rapidly upon entering fracture channels, rendering effective plug formation difficult.

Figure 3(b) illustrates the mechanism of gel-bridging coupled plugging. In the initial stage, uncrosslinked gel injected into high-permeability fractures, due to its low viscosity, is prone to leakage and loss with the fluid. Without a pilot structure, it is difficult for the gel to remain, expand, and gel within the channel. By adding bridging particles (rigid large particles, elastic micro-particles) to the gel system, a multi-scale physical plugging framework is first formed, which serves to achieve rapid initial plugging and flow rate regulation. Particles become embedded, bridge, and deposit within the fracture, particularly at fracture openings or in high-permeability zones, forming an initial “particle bridge plug” that effectively reduces local flow velocities and pressure gradients [

25]. Subsequently injected gel acts as an “adhesive,” adhering to particle surfaces and enveloping interparticle gaps to “bond” discrete particles into a cohesive whole, thereby forming a continuous, dense elastic network structure. The aforementioned composite plugging structure incorporates a dual mechanism of “rigid support + elastic bonding,” effectively enhancing the retention capability and high-pressure resistance of the plugging section. Therefore, gel-bridging coupled plugging not only addresses the issue of single gels struggling to retain effectively in high lost circulation channels but also significantly improves structural stability and mechanical properties post-gelation, demonstrating excellent adaptability to severe lost circulation formations and field application potential [

26].

4. Discussion of Experimental Results

4.1. Selection of Crosslinking Agents

When severe lost circulation occurs in the wellbore, control of the gel’s gelation time via gel plugging is essential to ensure adequate coverage of the severe lost circulation area by the gel. If gelation time is too short, the gel may gel before reaching the lost circulation area, preventing it from reaching the affected zone. If gelation time is too long, the gel may gel outside the loss area, resulting in poor plugging performance. The type of crosslinking agent significantly influences the gel’s gelation time [

19].

Polyvinyl alcohol gel (PVA Gel) can be prepared using various crosslinking agents and methods. The selection of crosslinking agents and methods affects the gel’s performance and characteristics. Glutaraldehyde, borax, and sodium tripolyphosphate will be used as crosslinking agents in the experiment to determine the system’s gelation time. Additionally, the ratio of pH adjusters will be adjusted to influence gelation time, thereby screening for the crosslinking agent with the most suitable gelation time. The base formulation used is: distilled water + 10% PVA + pH adjuster + crosslinking agent.

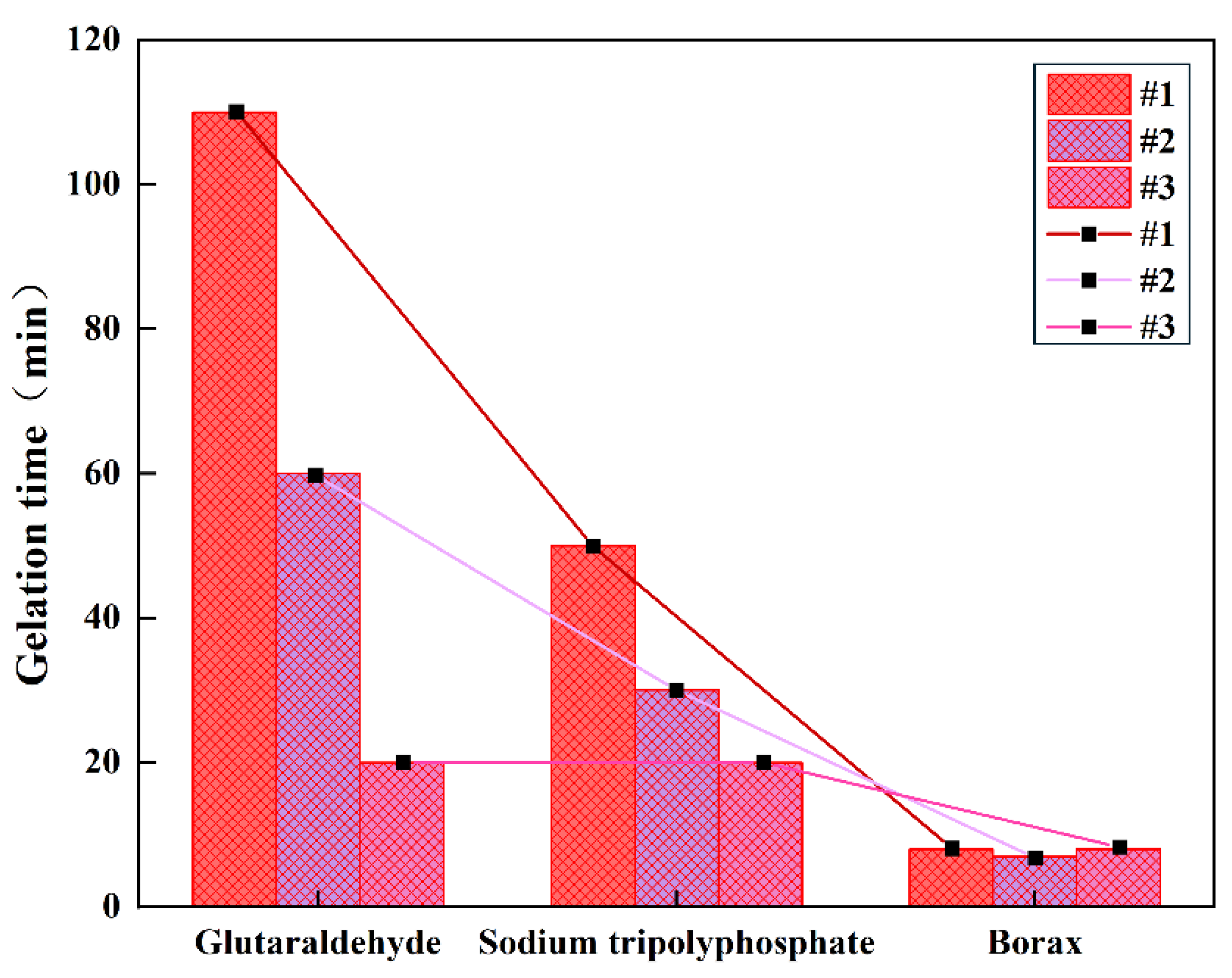

As shown in

Table 1, the use of different crosslinking agents does affect the gelation time of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) gel; notably, when glutaraldehyde is used as the crosslinking agent, gelation time is prolonged, and this can be controlled by adjusting the pH value. As shown in

Figure 4, the maximum gelation time can reach 110 minutes. A longer gelation time allows the gel system to enter the fracture from the wellbore smoothly, covering the entire lost circulation channel and forming an effective sealing structure. It also provides an extended time window for on-site construction.

4.2. Regulation of Gel Properties

In addition to crosslinking agent selection, factors such as polymer main agent amount, crosslinking agent concentration, and pH regulator dosage also influence the gel’s gelation time and mechanical properties. A composite pH regulator system using citric acid and sodium citrate was employed in this study, and orthogonal experiments (L9 (3

3)) were conducted to design a total of 9 experimental groups. The primary factors under investigation included polymer matrix dosage, crosslinking agent dosage, and the citric acid-to-sodium citrate ratio. The orthogonal experimental factor level table and orthogonal experimental results analysis table are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The most suitable gel system formulation for rotation was comprehensively determined by analyzing the effects of main agent concentration, crosslinking agent concentration, and pH regulator ratio on system gelation time, along with testing gel strength. Analysis of the orthogonal experimental results shows that range data comparison indicates factor C has the largest range value (75.66), making the citric acid-to-sodium citrate ratio the most significant factor influencing PVA Gel gelation time. pH values can influence the chemical environment of the crosslinking reaction, thereby enabling precise control of gelation time. Under different pH conditions, reaction rates between the crosslinking agent and polymer vary. Based on gel strength analysis, Experiment 6 was selected as the optimal formulation. Excessively high polymer concentrations may result in excessive solution viscosity, impacting gelation time and flowability during injection. The optimal main agent concentration is controlled at 10%. As shown in

Table 3, the gelation time of this polymer gel can be controlled between 20 and 120 minutes, enabling timely adjustment of gelation time during construction based on site conditions.

4.3. Selection of Optimal Gel Fillers

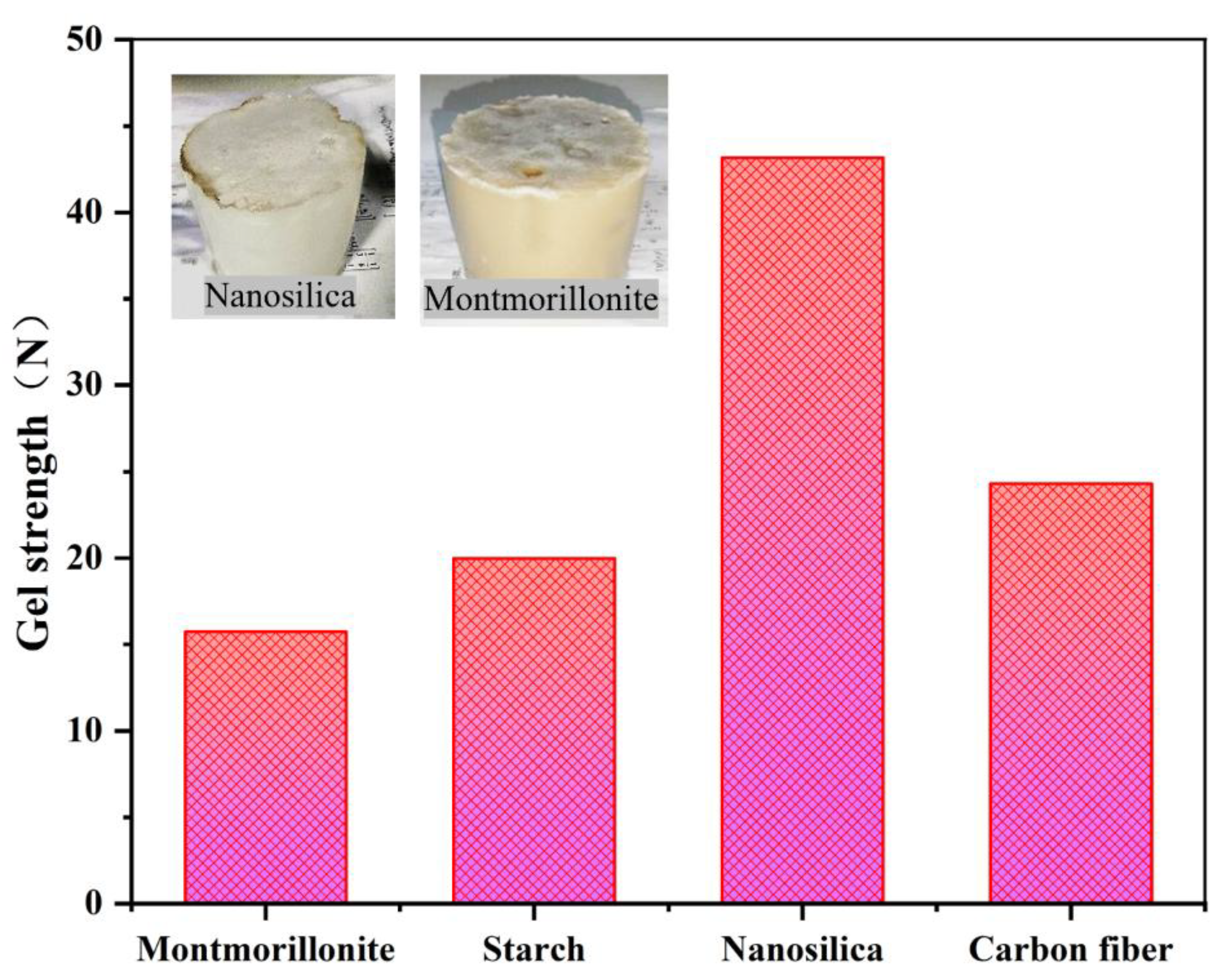

As shown in the orthogonal experiment results in

Table 3, the original strength of PVA Gel ranges from 4 to 22 N. To achieve higher strength, the gel’s strength was enhanced in this study by adding filler materials. After a review of relevant literature, 1% montmorillonite, starch, and nanosilica were selected as filler materials for experimentation, and gel strength was measured. Based on previously determined experimental conditions, the base formulation was 500 mL distilled water + 1% nanosilica + 10% PVA + 3% citric acid + 3% sodium citrate + 2% glutaraldehyde. The experimental results are presented in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5, the use of nanosilica as the gel filler material results in better enhancement of gel strength. Nanosilica is uniformly dispersed in the aqueous solution via ultrasonication, followed by the complete dissolution of PVA Gel in the solution, forming a stable dispersion system that effectively enhances the gel’s mechanical and functional properties. As observed in the physical sample images, the montmorillonite-containing gel exhibits a jelly-like consistency and is easily crushed. The nanosilica-containing gel exhibits better elasticity and greater toughness, rendering it less prone to crushing [

28]. The use of nanomaterials to enhance gel strength is a common method; for this purpose, stable dispersion of nanomaterials within the gel is essential. In the experiment, nanosilica exhibited excellent dispersion in the PVA polymer gel. Therefore, nanosilica was selected as the filler material. The resulting basic gel formulation was: distilled water + 10 wt% PVA particles + 3 wt% citric acid + 3 wt% sodium citrate + 1 wt% nanosilica + 2 wt% glutaraldehyde.

4.4. Selection of Optimal Gel Filler Addition Amount

To determine the appropriate amount of filler material, four basic formulations were established to investigate changes in gel properties. These included: a basic formulation without nanosilica, a basic formulation with 0.5 wt% nanosilica, a basic formulation with 1.0 wt% nanosilica, and a basic formulation with 1.5 wt% nanosilica.

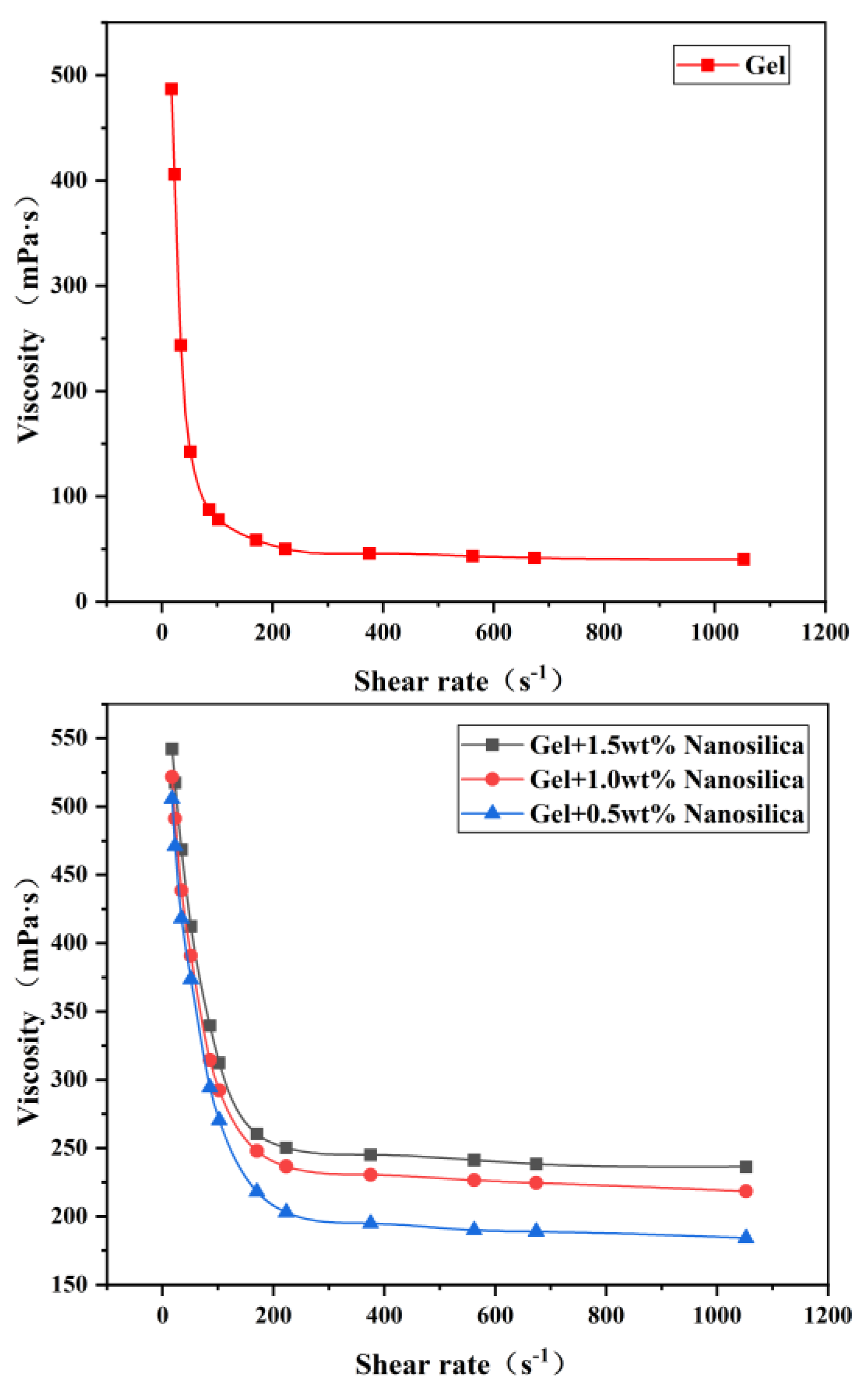

(1) Evaluation of gel rheological properties

As shown in

Figure 6, both the polymer gel before and after nanosilica addition exhibit shear-thinning characteristics, indicating that the prepared gel system can maintain a low viscosity and rapid flow state prior to being pumped to the target layer. A comparison of

Figure 6(a) and (b) reveals that the system’s viscosity increases significantly after nanosilica addition, with the decreasing trend becoming more gradual. This indicates that during the crosslinking reaction, nanosilica can form hydrogen bonds with polymer molecules and arrange themselves in an ordered manner within the polymer network structure, thereby significantly enhancing the strength of the gel structure [

27].

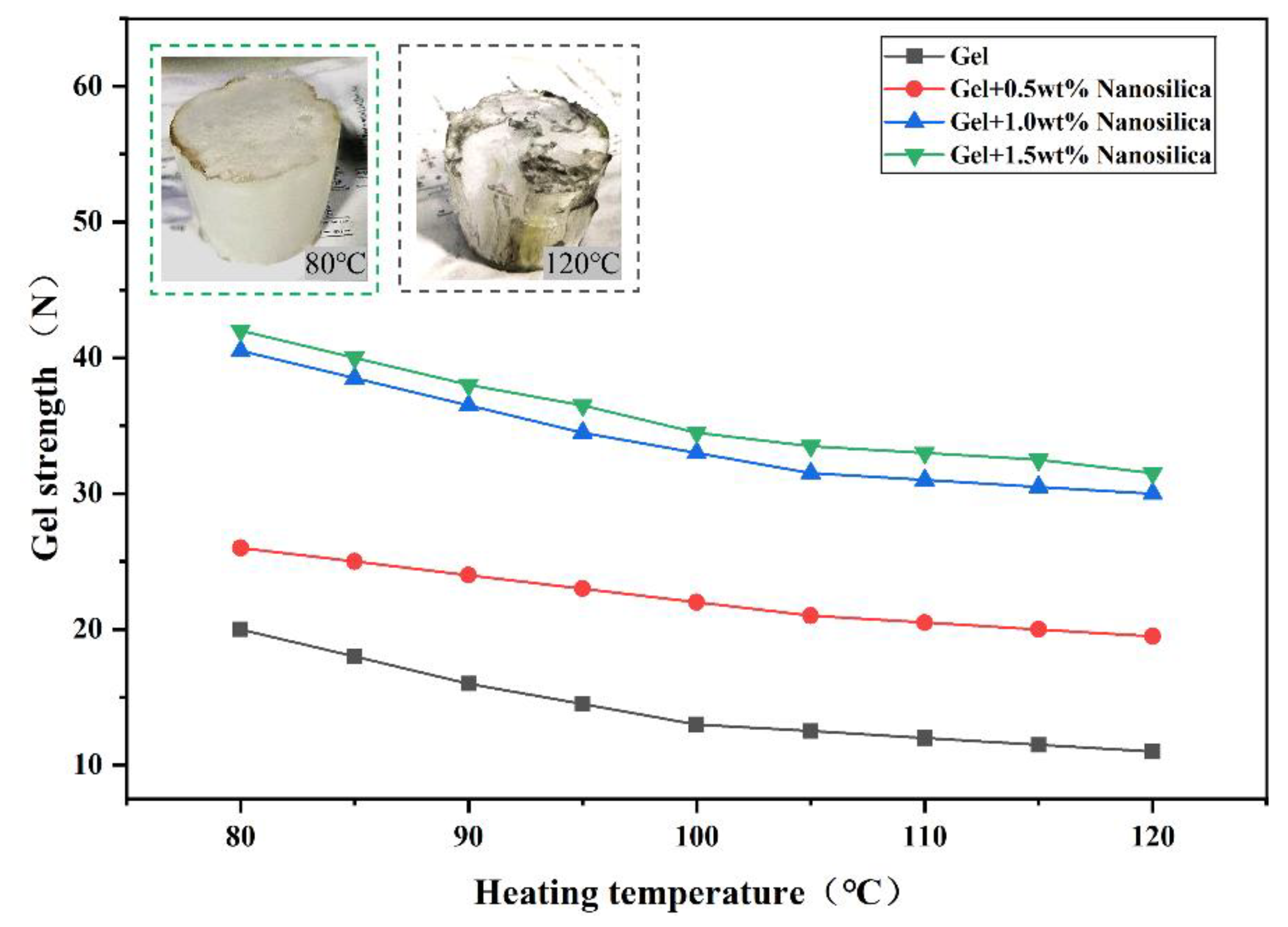

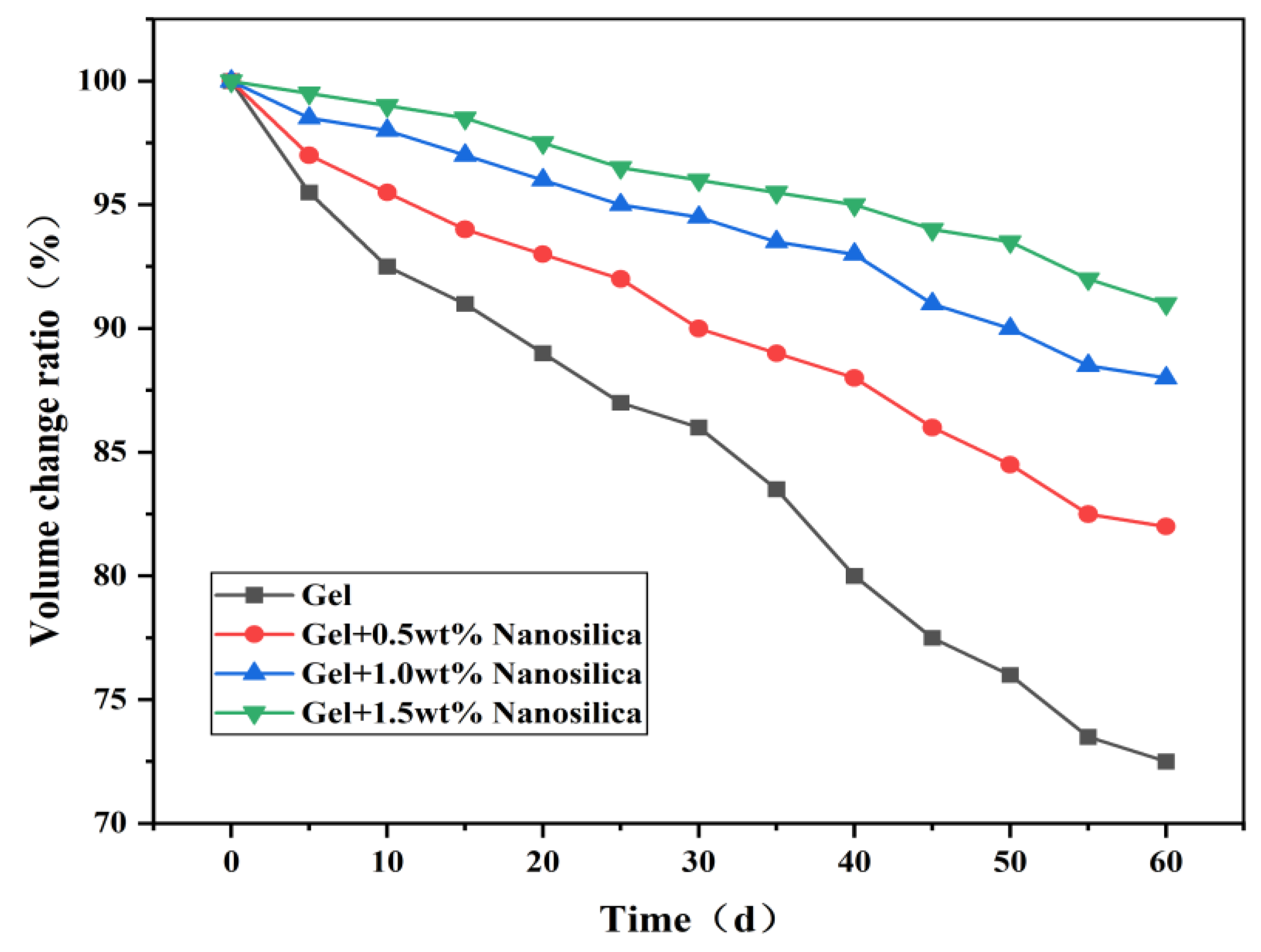

(2) Evaluation of the thermal resistance of the gel

Figure 7 shows four base formulations exhibit slight, non-significant gel strength decreases with increasing temperature. However, nanosilica-containing gels exhibit significantly higher strength than those without. This arises from nanosilica acting as a crosslinking agent during crosslinking, interacting with polymers to form a joint network and enhance overall gel strength.

Figure 8 shows gels without nanosilica shrink in volume over time at 120°C aging. This reflects polymer thermal degradation at high temperatures, causing gel shrinkage and volume decrease [

28]. However, nanosilica addition slows the gel’s volume change. This is due to nanosilica inhibiting polymer thermal degradation and forming hydrogen bonds with system water, resisting high-temperature evaporation and improving thermal stability.

Increasing nanosilica concentration increases crosslinking particles, raising crosslinking density and improving the gel system’s strength and thermal stability [

29]. At 1.0 wt%, gel strength and volume changes stabilize, indicating saturated crosslinking between nanosilica and polymers. Overall, 1% nanosilica addition leads to high-temperature gel strength decrease but retention above 30 N, meeting design requirements. Thus, a 1 wt% nanosilica base formulation was selected for subsequent experiments to investigate gel system and particle-gel composite properties.

4.5. Analysis of Temperature Sensitivity of Nanomaterials-Reinforced Gel Systems

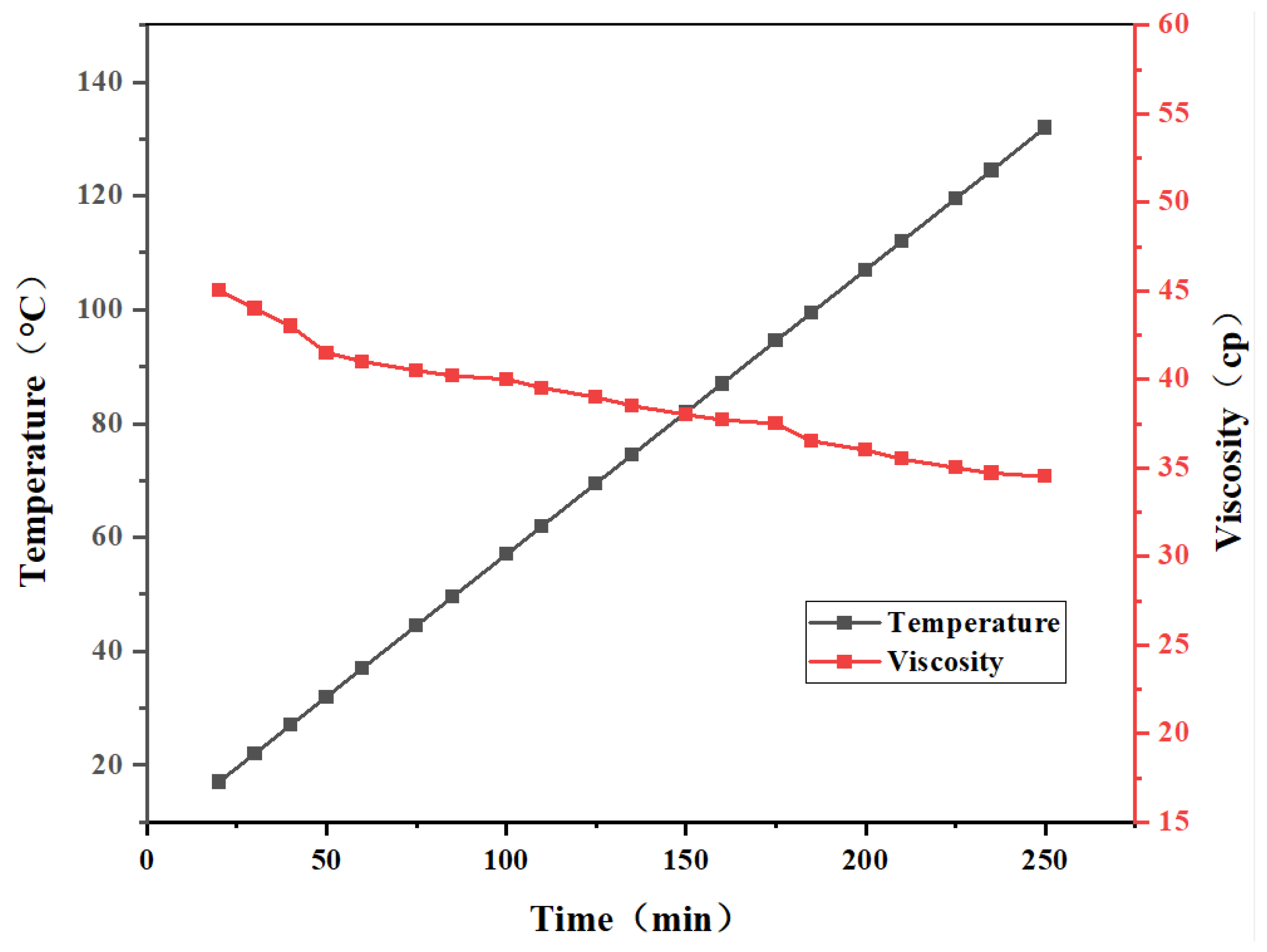

Viscosity changes of the gel system with 1.0 wt% nanosilica added under a specific temperature gradient are shown in

Figure 9. The results indicate that as temperature gradually increases from 20°C to 140°C, the gel system’s viscosity decreases slightly, with no significant overall change. The gel’s overall viscosity remains between 33,000 and 47,000 mPa·s, indicating that nanosilica addition can partially resist high-temperature damage to the gel system’s network structure [

30]. At its lowest viscosity, the gel can carry bridging particles into the fracture, facilitating fracture filling with bridging material, while thickening at the leakage site to significantly reduce fluid loss.

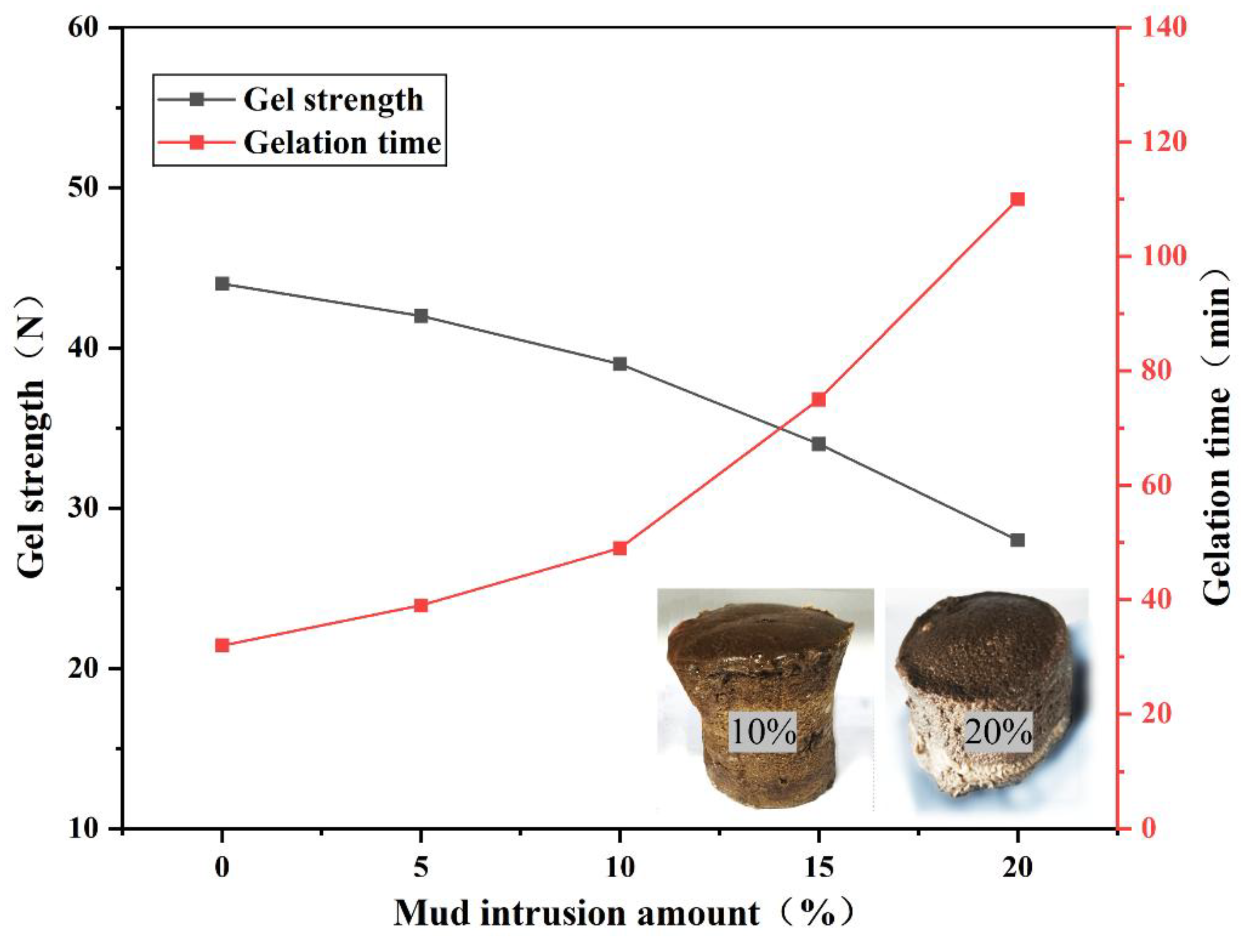

4.6. Contamination Resistance of Nanomaterials - Reinforced Gel Systems

As shown in

Figure 10, with increasing mud concentration, the gel system’s strength and gelation time change minimally at concentrations below 10.0 wt%. However, as concentration increases from 10% to 20%, the gel system’s strength changes by 12.8% and 17.6%, respectively, while gelation time changes by 53.1% and 46.6%, respectively. This indicates that water and solid particles in the mud significantly slow the crosslinking reaction rate while disrupting the gel system’s network structure, thereby affecting gel strength [

31]. To address prolonged gelation time, the pH of the gel solution can be adjusted by modifying the citric acid-to-sodium citrate ratio to control gelation time. A longer gelation time allows the gel system to enter the fracture from the wellbore smoothly, cover the entire lost circulation channel, and form an effective sealing structure. It also provides an extended time window for on-site construction [

32]. Furthermore, experimental results indicate that mud intrusion has minimal impact on gel system strength. Although increased mud intrusion gradually reduces gel system strength, at 20% intrusion, the gel system strength remains at 30 N, meeting sealing requirements and demonstrating excellent contamination resistance of the gel system.

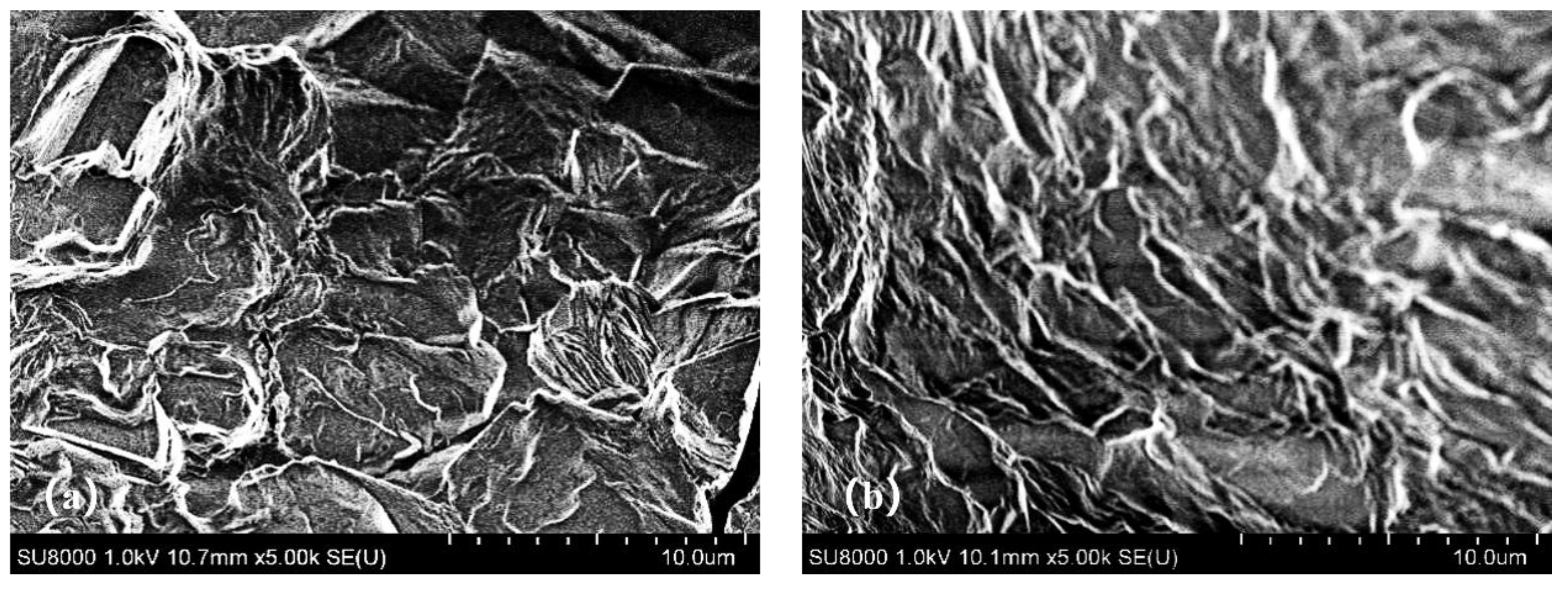

4.7. Microscopic Analysis of Nanomaterials-Reinforced Gel Systems

The scanning electron microscope microstructures of gel systems with and without nanosilica particles are shown in

Figure 11. As shown in

Figure 11(a), the surface of the gel system without nanosilica particles is relatively rough, with large pores and irregular structures. In contrast,

Figure 11(b) shows that following the introduction of nanosilica particles, the gel system exhibits a more uniform network structure. This indicates that nanosilica particles are uniformly distributed within the gel system network, where they serve a filling and reinforcing role, resulting in an overall finer and smoother structure [

33].

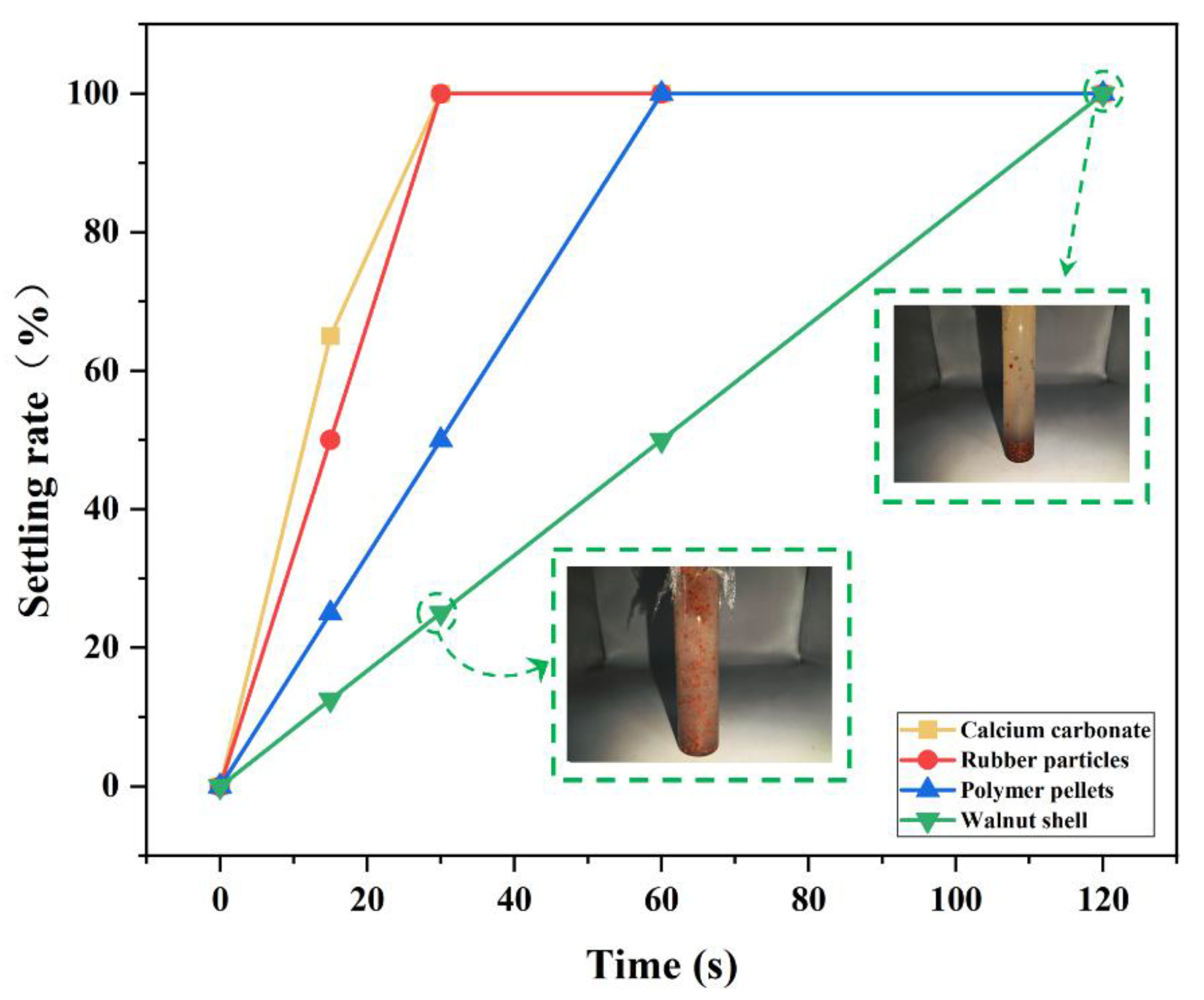

4.8. Optimal Bridging Plugging Material Compatible with Gel Systems

In the coupled bridging and gel plugging system, the primary function of bridging materials is to form bridges within lost circulation channels, thereby assisting the gel in remaining within such channels. Therefore, the suspension performance of bridging materials is particularly important. If the suspension performance of bridging materials is poor, bridging particles may not be effectively carried into lost circulation channels, and significant differences in plugging slurry concentration may occur between front and rear sections [

31]. In this study, four particle materials—walnut shells, calcium carbonate, rubber particles, and polymer particles—were selected to evaluate their suspension properties in the gel.

The experimental results are presented in

Figure 12. After stirring, calcium carbonate and rubber particles settled completely within 30 seconds, whereas polymer particles settled completely within 60 seconds. Due to their lowest density among plant materials and strong suspension capacity, walnut shells exhibited a settling rate of only 50% at 60 seconds and complete settling by 120 seconds, indicating the best settling stability. Therefore, walnut shells were ultimately selected as the bridging material for the coupled plugging method, with a gel system introduced to enhance the strength and shear resistance of the plugging structure [

32].

4.9. Evaluation of Gel-Bridging Coupled Plugging Method Under Simulated Severe Lost Circulation Conditions

The fracture plugging simulation experiment is designed to simulate the plugging state of gel in a geological formation environment, thereby assessing the quality of plugging in lost circulation channels and providing validation for the actual simulation process of plugging fractured leaking formations. A fracture plugging simulation device manufactured by Hai’an Petroleum Technology Co., Ltd. is used to evaluate the plugging effect. The fracture module is composed of steel, shaped as a wedge-shaped fracture with a width range of 5–8 mm. Plugging results are indicated by pressure-bearing capacity and lost circulation volume. Under conditions simulating large subsurface formation fractures using a 7 mm natural fracture, different leak plugging methods were employed to seal the fracture. The sealing capabilities of the different methods were evaluated based on lost circulation volume and pressure-bearing capacity during the fracture sealing process. The selected methods included bridging plugging, gel plugging, and coupled plugging.

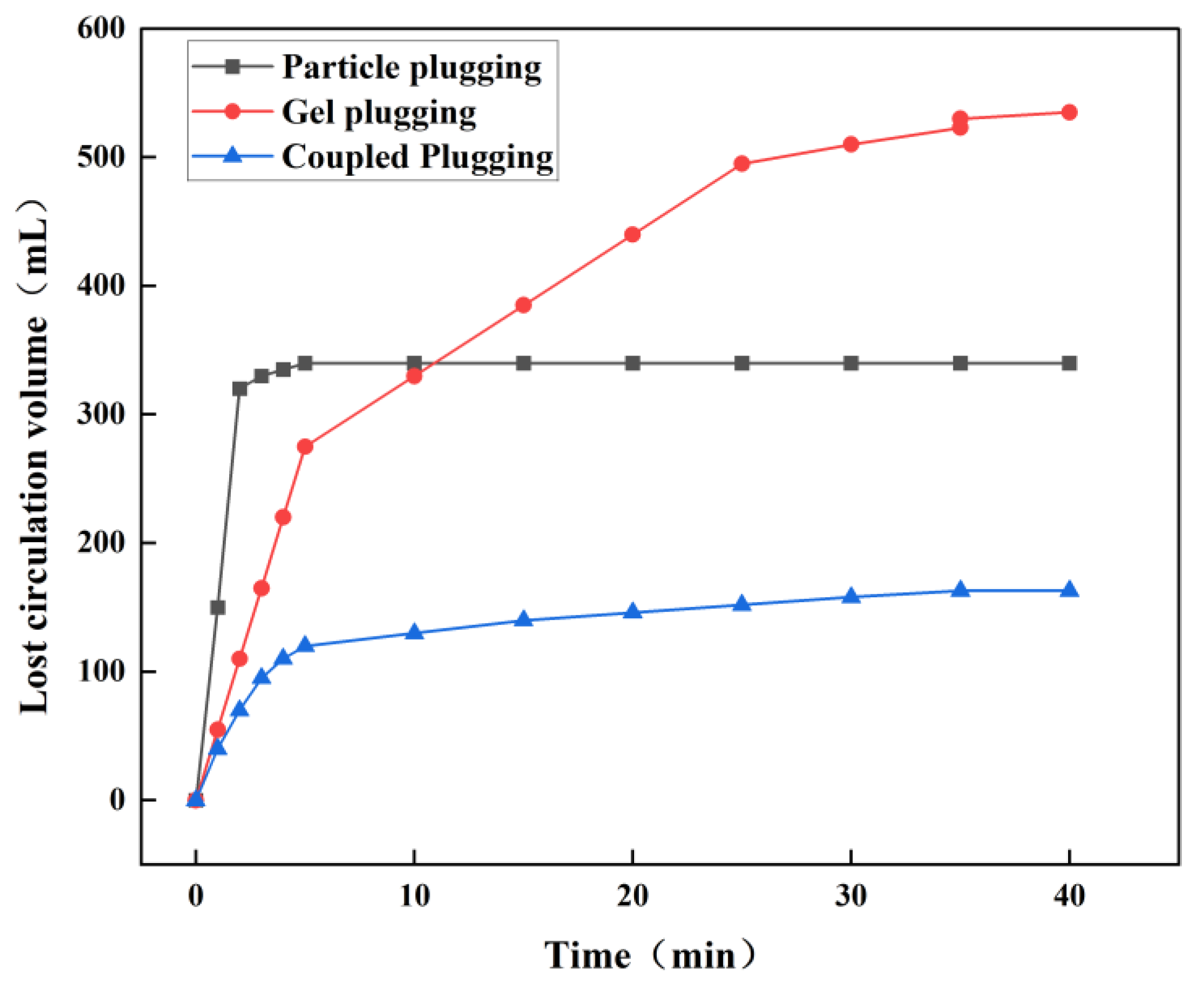

(1) Relationship between lost circulation volume and time under three leak plugging methods for a 7 mm fracture.

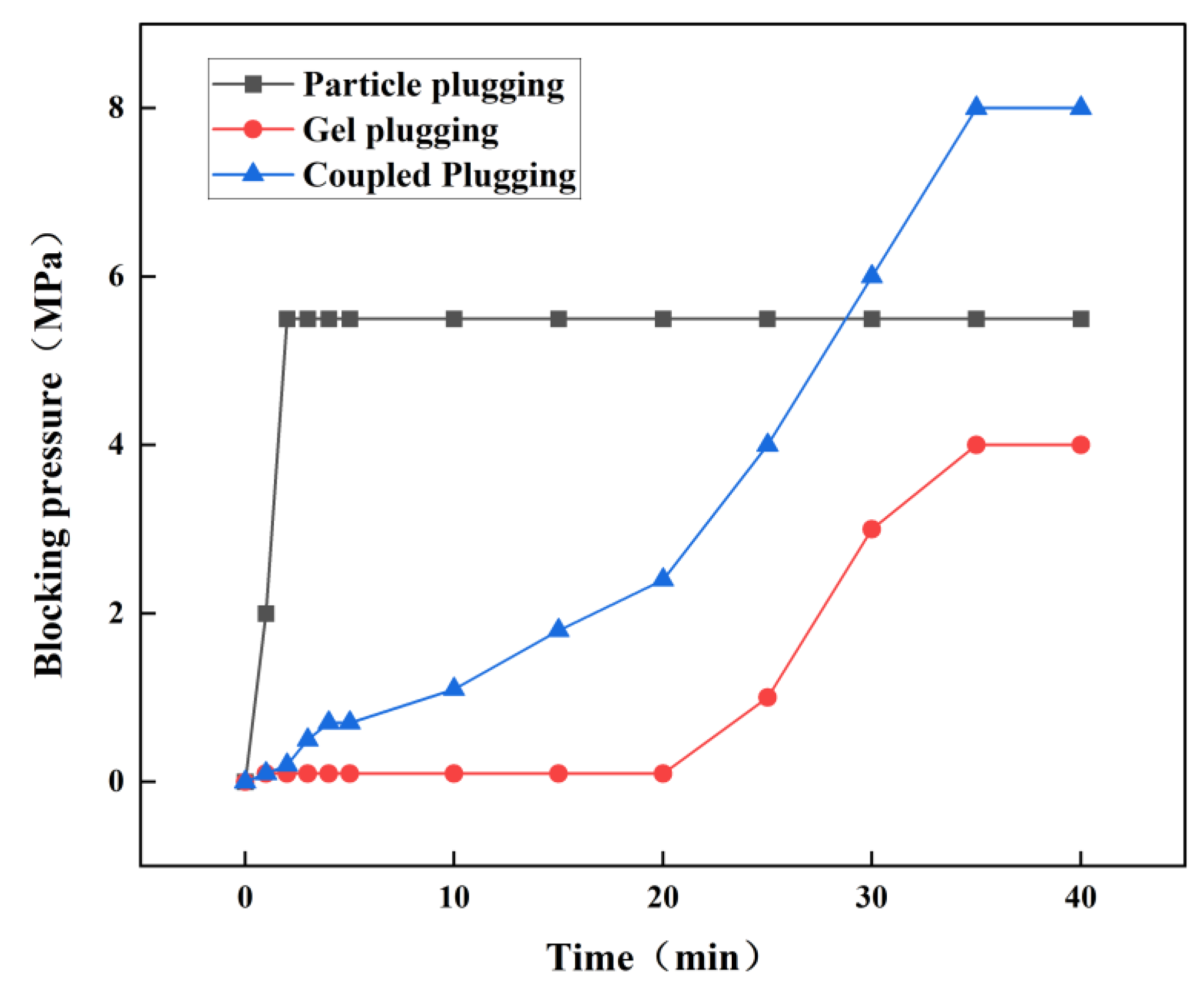

(2) Relationship between downward pressure and time for three leak plugging methods under a 7 mm fracture

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show particle plugging exhibits rapid pressure rise within 5 minutes, with particles quickly forming a supporting skeleton at the fracture entrance. However, loose particle bridging causes rapid increases in lost circulation volume. Pressure stabilizes at 5.5 MPa with lost circulation volume at 340 mL, as particles fill skeleton gaps to form a denser plugging layer. However, large particles primarily fill the fracture entrance, risking re-leakage during reconstruction [

33]. Gel plugging initially involves uncrosslinked gel with low flow resistance and higher lost circulation volume. Gel crosslinking increases over time, increasing flow resistance. At 5 minutes, lost circulation volume is 275 mL (slowing rate); at 25 minutes, it reaches 495 mL and stabilizes.

Figure 14 shows pressure rises after 20 minutes, indicating gel network formation and effective plugging. Coupled plugging involves initial particle skeleton formation, obstructing gel flow with pressure rising slowly to 0.7 MPa at 5 minutes. Crosslinking increases over time, with particles filling remaining spaces. At 8 MPa, lost circulation volume stabilizes at 163 mL with pressure stabilization, indicating a stable composite sealing layer [

34].

A comparison of the plugging performance of different leak plugging methods reveals that in bridging plugging, particle bridging within the fracture is of poor quality, resulting in weak pressure-bearing capacity, a loose plugging layer, and a high likelihood of re-leakage. This aligns well with actual on-site conditions. The gel plugging method also exhibits insufficient pressure-bearing capacity in large fractures, indicating that gel alone lacks adequate compressive and shear resistance within such fractures. Mechanical strength is enhanced in the coupled plugging method by incorporating particles into the gel system to form more robust plugging segments. This highlights the critical role of physical bridging materials within the gel system.

5. Conclusions

Gel-bridging coupled plugging technology, which involves the addition of nanomaterials and plugging particles to the gel, offers advantages over single leak plugging methods. Its mechanism of action involves two aspects: nanomaterials can significantly enhance the gel’s thermal resistance and mechanical properties; the bridging agent acts as a supporting skeleton, working with the gel to form an elastic network structure that helps form a more stable plugging structure after gelation.

After testing the rheological properties and thermal resistance of four base gel formulations, 1.0 wt% nanosilica particles were selected as the optimal filler material. Performance evaluation of the optimized gel system revealed that at an aging temperature of 120°C, gel strength reached 30 N, with rheological properties remaining relatively stable across different temperatures (33,000–47,000 mPa·s). The system exhibits low viscosity, ease of pumping, strong gel strength after gelation, and excellent thermal and contamination resistance.

Walnut shells were selected as the bridging material to enhance the sealing strength and shear resistance of the gel-bridging composite system. Experimental results from a 7 mm wide fracture plugging test show that the plugging pressure of the gel-bridging coupled plugging system reaches 8 MPa, with lost circulation volume controlled at 163 mL. Compared to single gel or bridging plugging methods, the coupled method exhibits lower lost circulation volume, higher pressure-bearing capacity, and better mechanical strength of the formed plugging layer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Fuhao Bao and Lei Pu; methodology, Fuhao Bao; software, Fuhao Bao; validation, Lei Pu; formal analysis, Fuhao Bao and Lei Pu; investigation, Fuhao Bao; resources, Lei Pu; data curation, Fuhao Bao; writing—original draft preparation, Fuhao Bao; writing—review and editing, Fuhao Bao and Lei Pu; visualization, Lei Pu; supervision, Lei Pu; project administration, Lei Pu; funding acquisition, Lei Pu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Open Foundation of Cooperative Innovation Center of Unconventional Oil and Gas, Yangtze University (Ministry of Education & Hubei Province), No. UOG2024-10 and the Open Fund of Hubei Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Engineering (Yangtze University),No, YQZC 202513.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank The Bakken Laboratory of YANGTZE University for their support. At the same time, I would like to thank my teacher Mingbiao Xu for his help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zheng, X.; Duan, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cui, X.; Qin, D. Application of Solvent-Assisted Dual-Network Hydrogel in Water-Based Drilling Fluid for Lost Circulation Treatment in Fractured Formation. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 1166–1173. [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.; Tian, L.; Wang, X. Effect of Nano-SiO2 on the Performance of Modified Cement-Based Materials. Integrated Ferroelectrics 2021, 216, 151–167. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tang, T.; Ou, B.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J. High Strength and Strong Thixotropic Gel Suitable for Oil and Gas Drilling in Fractured Formation. Gels 2025, 11, 578. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ge, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, M. New Insights and Experimental Investigation of High-Temperature Gel Reinforced by Nano-SiO2. Gels 2022, 8, 362. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, L.; Fu, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. Study on Plugging Mechanism of Gel Plugging Agent in Fractured Carbonate Oil Reservoirs. Chem Technol Fuels Oils 2023, 59, 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Al Ramadan, M.; Aljawad, M.S. Long-Term Investigation of Nano-Silica Gel for Water Shut-Off in Fractured Reservoirs. Gels 2024, 10, 651. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Chi, L.; He, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L. Evaluating and Study of Natural Gas Injecting in Shunbei-1 Block Fault-Controlled Fractured-Cavity Type Reservoir. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1399921. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Development Characteristics of Silurian Strike-Slip Faults and Fractures and Their Effects on Drilling Leakage in Shunbei Area of Tarim Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 938765. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, R.; Zhou, J.; Chen, H.; Tan, Y. A Novel Hyper-Cross-Linked Polymer for High-Efficient Fluid-Loss Control in Oil-Based Drilling Fluids. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 626, 127004. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Jiang, M.; Xu, J.; Xu, M.; Meng, S.; Wang, D. Design and Plugging Property of Composite Pressure Activated Sealant. Natural Gas Industry B 2020, 7, 557–565. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Niu, C.-C.; Yang, X.-Y. Improved Understanding Nanocomposite Gel Working Mechanisms: From Laboratory Investigation to Wellbore Plugging Application. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2020, 191, 107214. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Deng, Z.; He, Y.; Li, Z.; Ni, X. Cross-Linked Polyacrylamide Gel as Loss Circulation Materials for Combating Lost Circulation in High Temperature Well Drilling Operation. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 181, 106250. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, Q.; Zhang, D. A Novel Targeted Plugging and Fracture-adaptable Gel Used as a Diverting Agent in Fracturing. Energy Science & Engineering 2020, 8, 116–133. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Shi, X.; Hu, G. Research Progress of High-Temperature Resistant Functional Gel Materials and Their Application in Oil and Gas Drilling. Gels 2022, 9, 34. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.-R.; Dai, L.-Y.; Sun, J.-S.; Jiang, G.-C.; Lv, K.-H.; Cheng, R.-C.; Shang, X.-S. Plugging Performance and Mechanism of an Oil-Absorbing Gel for Lost Circulation Control While Drilling in Fractured Formations. Petroleum Science 2022, 19, 2941–2958. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Deng, Z.; He, Y.; Li, Z.; Ni, X. Cross-Linked Polyacrylamide Gel as Loss Circulation Materials for Combating Lost Circulation in High Temperature Well Drilling Operation. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2019, 181, 106250. [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Tchameni, A.P.; Luo, M.; Wen, J. Enhanced Hydrophobically Modified Polyacrylamide Gel for Lost Circulation Treatment in High Temperature Drilling. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2021, 325, 115155. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Bai, B.; Hou, J. Polymer Gel Systems for Water Management in High-Temperature Petroleum Reservoirs: A Chemical Review. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 13063–13087. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Chaudhry, S. High-Performance Silica Nanoparticle Reinforced Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) as Templates for Bioactive Nanocomposites. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2013, 33, 2601–2610. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Development of Nanomontmorillonite-Reinforced Terpolymer Gels for High-Temperature Petroleum Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 8579–8588. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, C. A Polymer Plugging Gel for the Fractured Strata and Its Application. Materials 2018, 11, 856. [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, L.J.; Giraldo, M.A.; Llanos, S.; Maya, G.; Zabala, R.D.; Nassar, N.N.; Franco, C.A.; Alvarado, V.; Cortés, F.B. The Effects of SiO2 Nanoparticles on the Thermal Stability and Rheological Behavior of Hydrolyzed Polyacrylamide Based Polymeric Solutions. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering 2017, 159, 841–852. [CrossRef]

- Hamza, A.; Shamlooh, M.; Hussein, I.A.; Nasser, M.S.; Salehi, S. Rheology of Triamine Functionalized Silica Reinforced Polymeric Gels Developed for Conformance Control Applications. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 1093–1098. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.-J.; Zhu, D.-Y.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Qin, J.-H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Hou, J.-R. Effect of Nano TiO2 and SiO2 on Gelation Performance of HPAM/PEI Gels for High-Temperature Reservoir Conformance Improvement. Petroleum Science 2023, 20, 3819–3829. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ge, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, A. Enhancing Temperature Resistance of Polymer Gels by Hybrid with Silica Nanoparticles. Petroleum Science and Technology 2022, 40, 3037–3059. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Luo, P. Research and Performance Evaluation of Modified Nano-silica Gel Plugging Agent. J of Applied Polymer Sci 2023, 140, e53873. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, L.; Dong, G.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z. High-Temperature-Resistant and Gelation-Controllable Silica-Based Gel for Water Management. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 23398–23406. [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Seddiqi, K.N.; Hou, J.; Fujii, H. Experimental Performance Evaluation and Optimization of a Weak Gel Deep-Profile Control System for Sandstone Reservoirs. ACS Omega 2024, acsomega.3c10244. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.; Menzel, C.; Johansson, C.; Andersson, R.; Koch, K.; Järnström, L. The Effect of pH on Hydrolysis, Cross-Linking and Barrier Properties of Starch Barriers Containing Citric Acid. Carbohydrate Polymers 2013, 98, 1505–1513. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, L.; Fu, M.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y. Study on Plugging Mechanism of Gel Plugging Agent in Fractured Carbonate Oil Reservoirs. Chem Technol Fuels Oils 2023, 59, 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Huang, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; He, J. Nano-Film-Forming Plugging Drilling Fluid and Bridging Cross-Linking Plugging Agent Are Used to Strengthen Wellbores in Complex Formations. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 22804–22810. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zuo, J. Experimental Investigation on the Nanosilica-Reinforcing Polyacrylamide/Polyethylenimine Hydrogel for Water Shutoff Treatment. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 6650–6656. [CrossRef]

- Qi, N.; Li, B.; Chen, G.; Liang, C.; Ren, X.; Gao, M. Heat-Generating Expandable Foamed Gel Used for Water Plugging in Low-Temperature Oil Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 1126–1131. [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Su, C.; Liu, C.; Cao, W.; He, X.; Ding, H.; Mei, J.; Yan, K.; Cheng, Q.; Lu, X. Synthesis and Performance Evaluation of an Organic/Inorganic Composite Gel Plugging System for Offshore Oilfields. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 12870–12878. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Simulation of natural large fracture plugging experimental apparatus.

Figure 1.

Simulation of natural large fracture plugging experimental apparatus.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of nanomaterials-reinforced gel against high temperature and mechanical properties.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of nanomaterials-reinforced gel against high temperature and mechanical properties.

Figure 3.

Gel-bridged coupled plugging method(a) Conventional gel plugging mechanism(b)Gel-bridging coupled plugging mechanism.

Figure 3.

Gel-bridged coupled plugging method(a) Conventional gel plugging mechanism(b)Gel-bridging coupled plugging mechanism.

Figure 4.

The effect of different crosslinking agents on the gelation time of gel.

Figure 4.

The effect of different crosslinking agents on the gelation time of gel.

Figure 5.

The effect of different crosslinking agents on the gelation time of gel.

Figure 5.

The effect of different crosslinking agents on the gelation time of gel.

Figure 6.

Apparent viscosity of gel as a function of shear rate (a) Gel without nanosilica (b) Gel with nanosilica added.

Figure 6.

Apparent viscosity of gel as a function of shear rate (a) Gel without nanosilica (b) Gel with nanosilica added.

Figure 7.

Strength changes of each gel at different temperatures.

Figure 7.

Strength changes of each gel at different temperatures.

Figure 8.

Volume change ratio of each gel at an aging temperature of 120°C.

Figure 8.

Volume change ratio of each gel at an aging temperature of 120°C.

Figure 9.

Analysis of temperature sensitivity of nanomaterials-reinforced gel systems.

Figure 9.

Analysis of temperature sensitivity of nanomaterials-reinforced gel systems.

Figure 10.

Changes in gelation time and gel strength of nanomaterials-reinforced gel systems.

Figure 10.

Changes in gelation time and gel strength of nanomaterials-reinforced gel systems.

Figure 11.

Scanning electron microscope microstructure of nanomaterials-reinforced gel systems (a) Gel system without nanoparticles (b) Gel system with 1.0 wt% nanoparticles added.

Figure 11.

Scanning electron microscope microstructure of nanomaterials-reinforced gel systems (a) Gel system without nanoparticles (b) Gel system with 1.0 wt% nanoparticles added.

Figure 12.

Changes in the settling rate of various bridging plugging materials over time.

Figure 12.

Changes in the settling rate of various bridging plugging materials over time.

Figure 13.

The relationship between lost circulation volume and time for the three leak plugging methods under a 7mm fracture.

Figure 13.

The relationship between lost circulation volume and time for the three leak plugging methods under a 7mm fracture.

Figure 14.

The relationship between blocking pressure and time for the three leak plugging methods under a 7mm fracture.

Figure 14.

The relationship between blocking pressure and time for the three leak plugging methods under a 7mm fracture.

Table 1.

Gel base formula using different crosslinking agents.

Table 1.

Gel base formula using different crosslinking agents.

| Formula |

Crosslinking agent |

PH adjuster |

| ➀ |

#1 |

2.0% glutaraldehyde |

1.5% citric acid + 4.5% sodium citrate |

| #2 |

2.0% glutaraldehyde |

2.0% citric acid + 4.0% sodium citrate |

| #3 |

2.0% glutaraldehyde |

3.0% citric acid + 3.0% sodium citrate |

| ➁ |

#1 |

1.0% borax |

1.5% citric acid + 4.5% sodium citrate |

| #2 |

1.0% borax |

2.0% citric acid +4.0% sodium citrate |

| #3 |

1.0% borax |

3.0% citric acid +3.0% sodium citrate |

| ➂ |

#1 |

1.0% Sodium tripolyphosphate |

1.5% citric acid +4.5% sodium citrate |

| #2 |

1.0% Sodium tripolyphosphate |

2.0% citric acid +4.0% sodium citrate |

| #3 |

1.0% Sodium tripolyphosphate |

3.0% citric acid +3.0% sodium citrate |

Table 2.

L9 (33) Orthogonal experimental factor level table.

Table 2.

L9 (33) Orthogonal experimental factor level table.

| Horizontal |

Factors |

| A (main agent concentration/% ) |

B (crosslinking agent concentration/% ) |

C (citric acid: sodium citrate) |

| 1 |

8% |

1.5% |

1:3 |

| 2 |

10% |

2% |

1:2 |

| 3 |

12% |

2.5% |

1:1 |

Table 3.

Analysis table of L9 (33) orthogonal experiment results.

Table 3.

Analysis table of L9 (33) orthogonal experiment results.

| Serial number |

Factors |

Gelation time/min |

Gel strength/N |

| A |

B |

C |

| Experiment 1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

111 |

4.27 |

| Experiment 2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

83 |

19.73 |

| Experiment 3 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

23 |

16.86 |

| Experiment 4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

57 |

21.27 |

| Experiment 5 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

42 |

12.38 |

| Experiment 6 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

120 |

21.21 |

| Experiment 7 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

19 |

23.62 |

| Experiment 8 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

80 |

20.96 |

| Experiment 9 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

65 |

14.83 |

| Mean A |

72.33 |

62.33 |

103.66 |

|

| Mean B |

67.33 |

62.66 |

68.33 |

|

| Mean C |

54.66 |

69.33 |

28 |

|

| extreme difference |

17.67 |

7 |

75.66 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).