Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Scaffolds

2.3. Characterization of Scaffolds

2.3.1. Morphology and Elemental Analysis

2.3.2. Structure

2.3.3. Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and Thermogravimetry (TGA)

2.3.4. Physical-Chemical Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.3.5. Bio-Chemical Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.3.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3. Results and Discussion

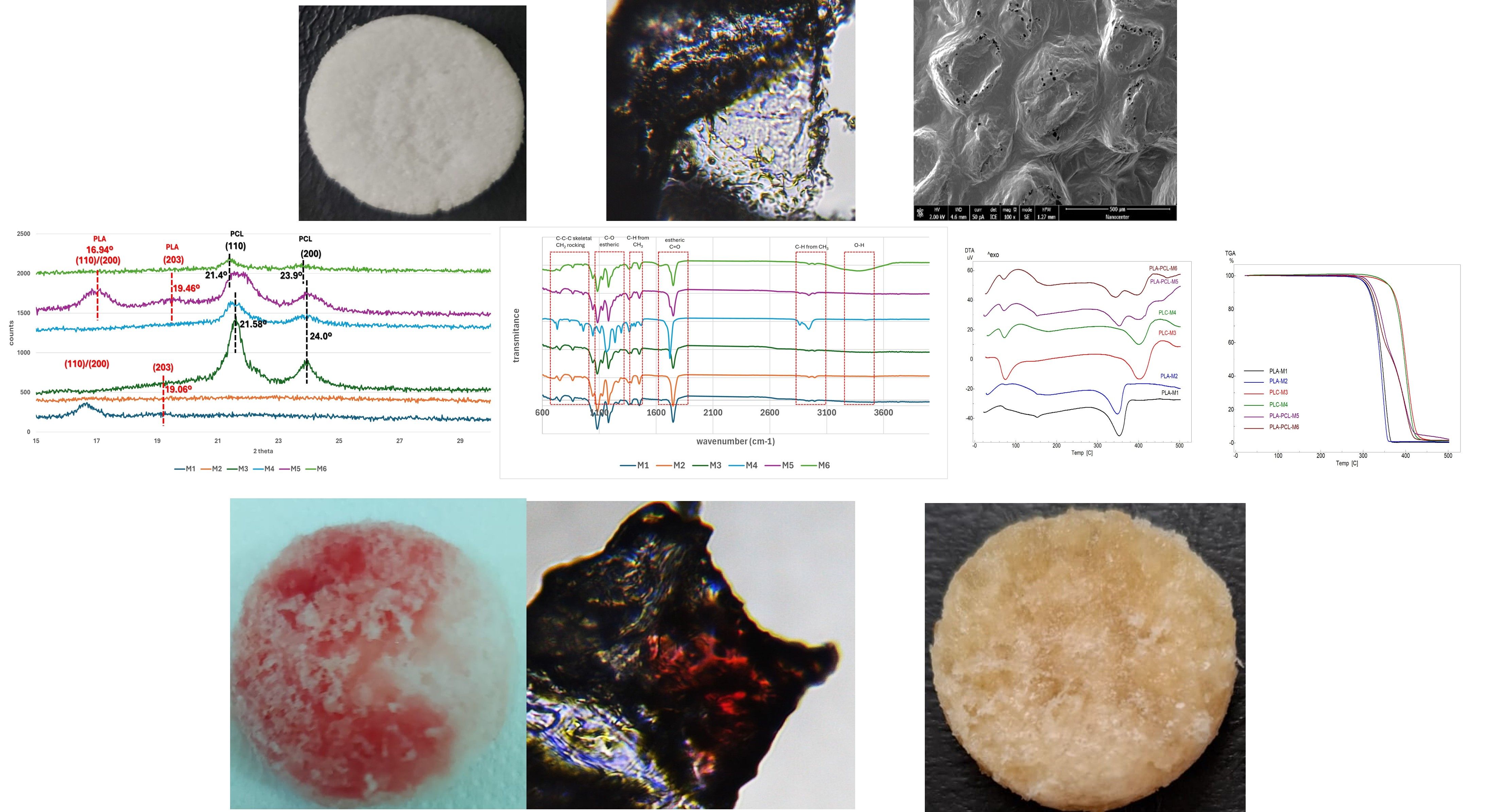

3.1. Morphology and Elemental Analysis

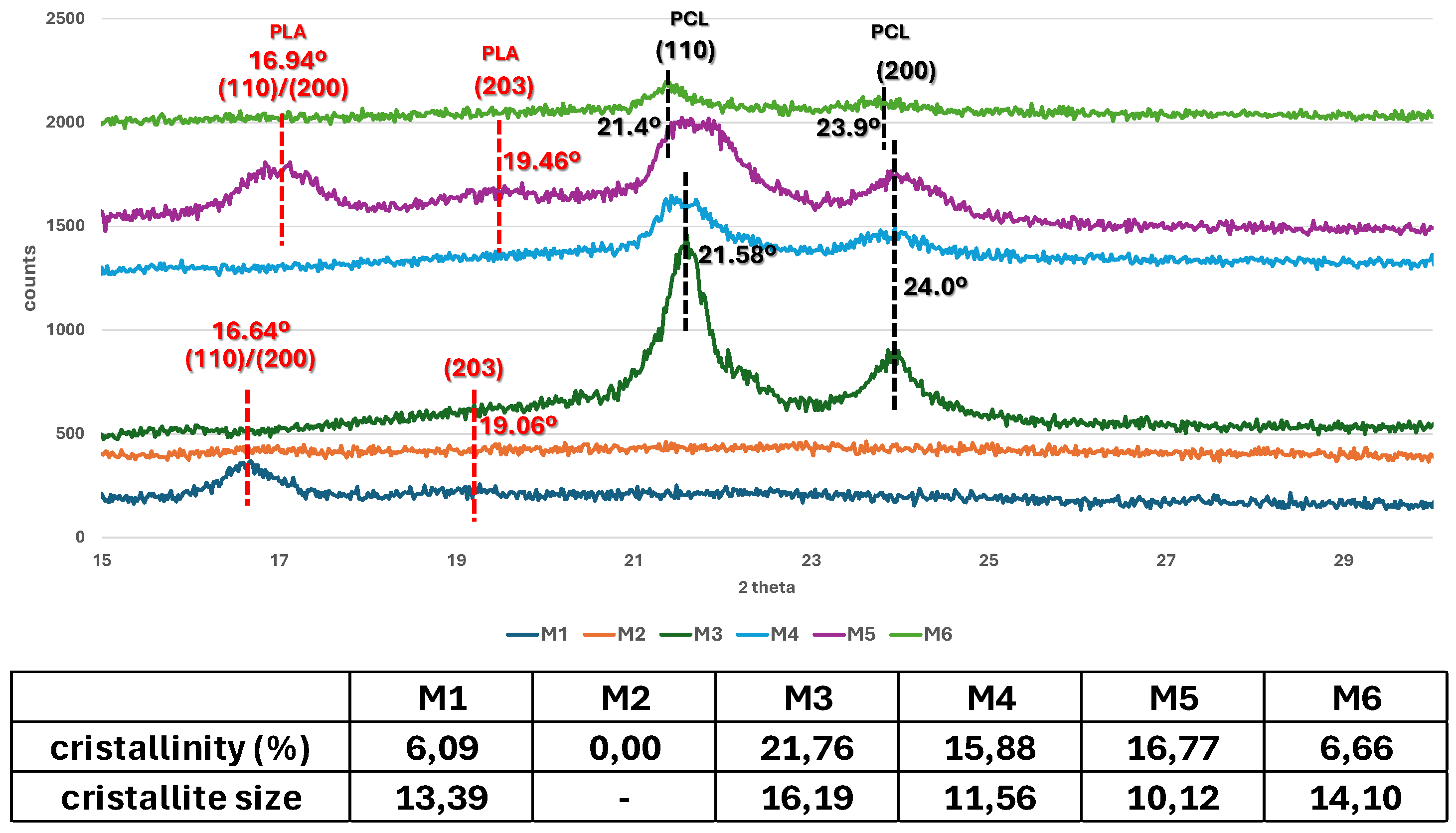

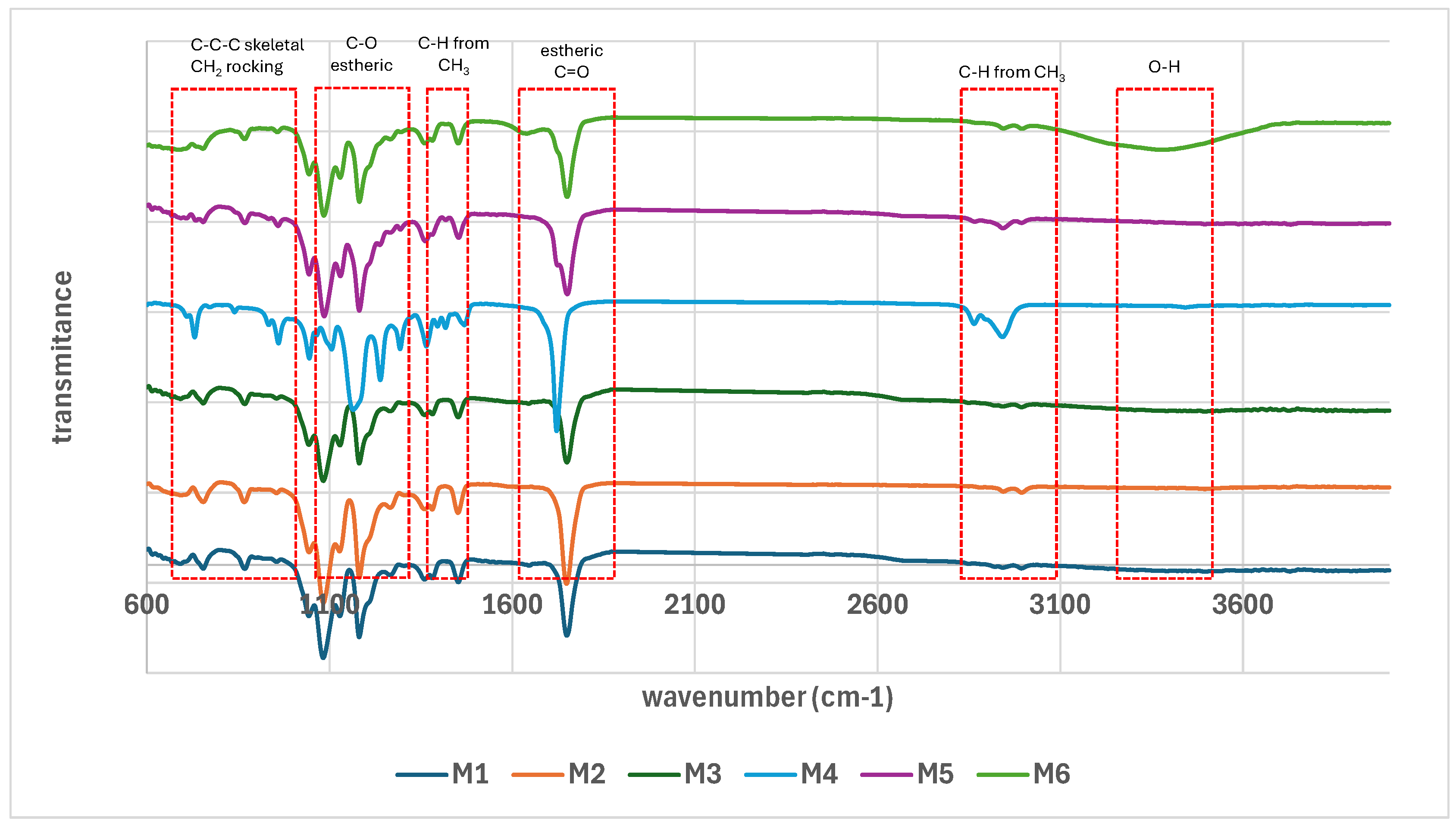

3.2. Structure of the Scaffolds

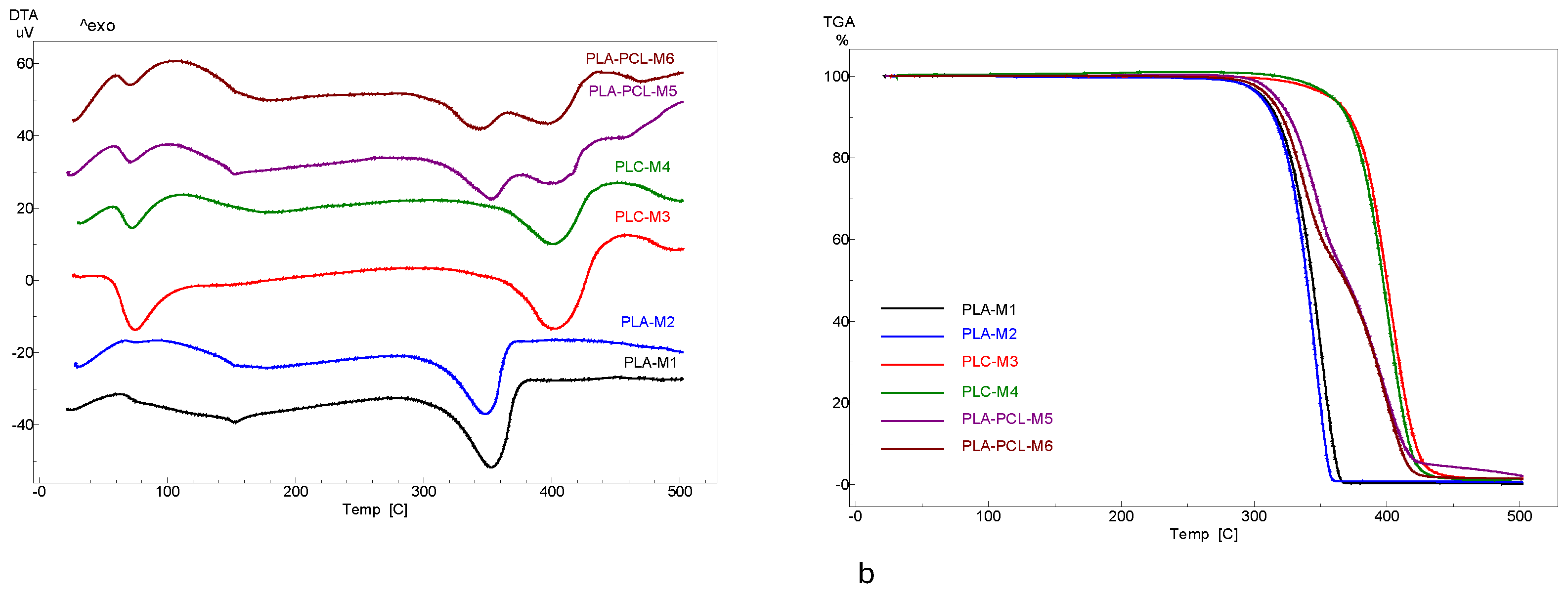

3.3. Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and Thermogravimetry (TGA)

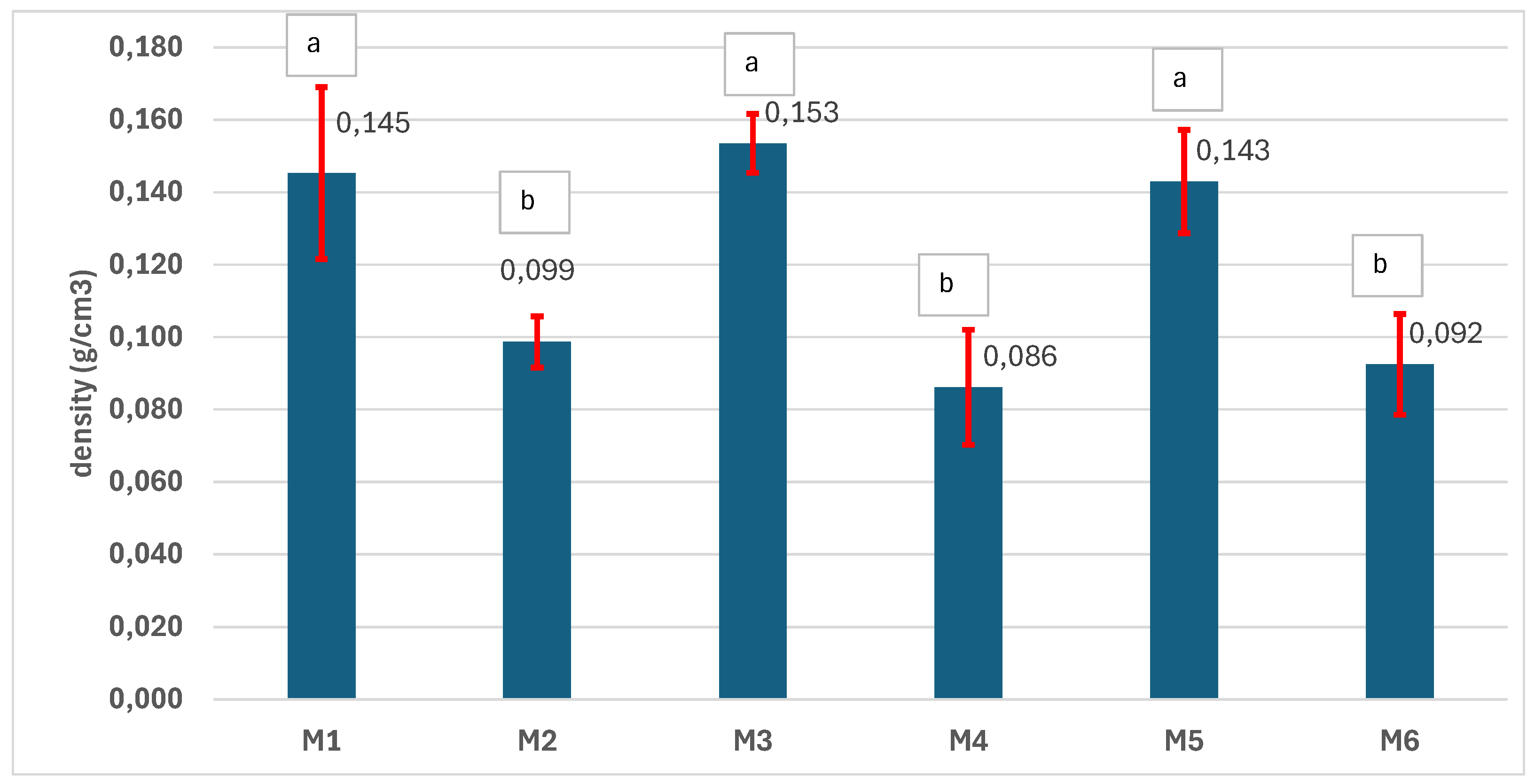

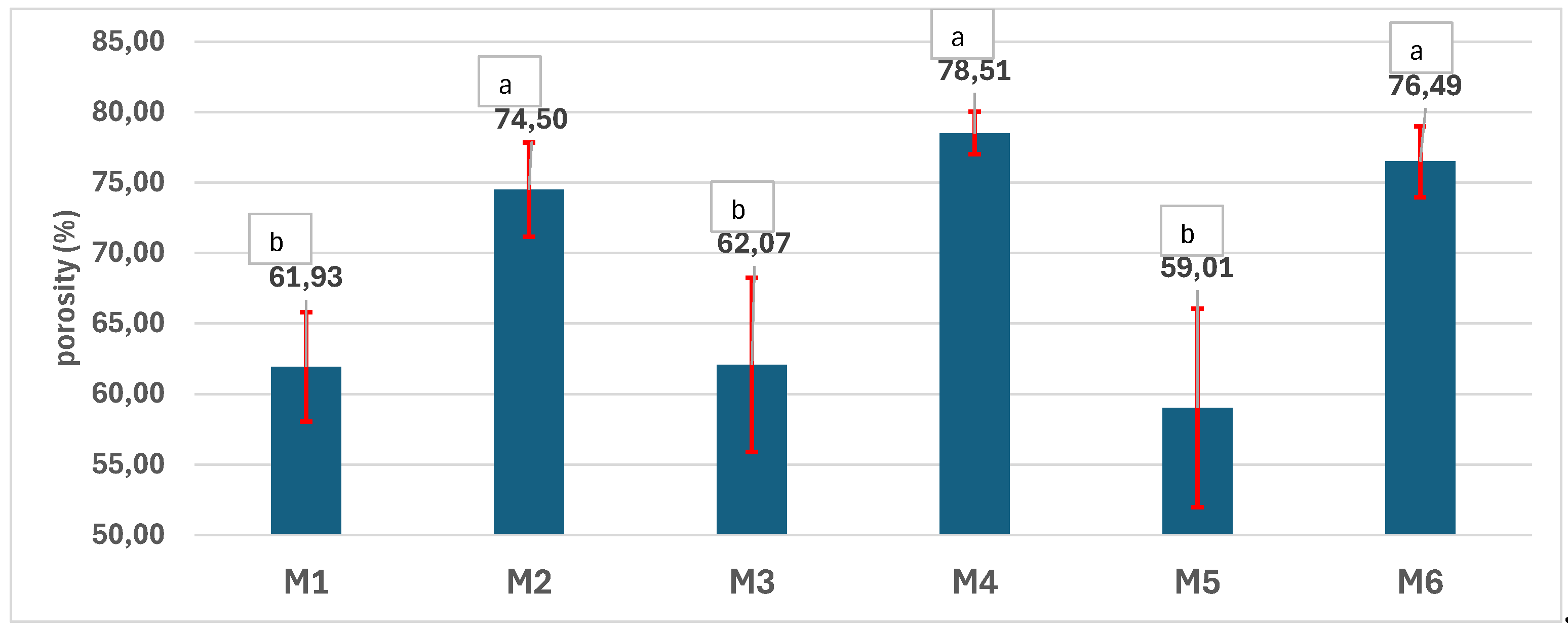

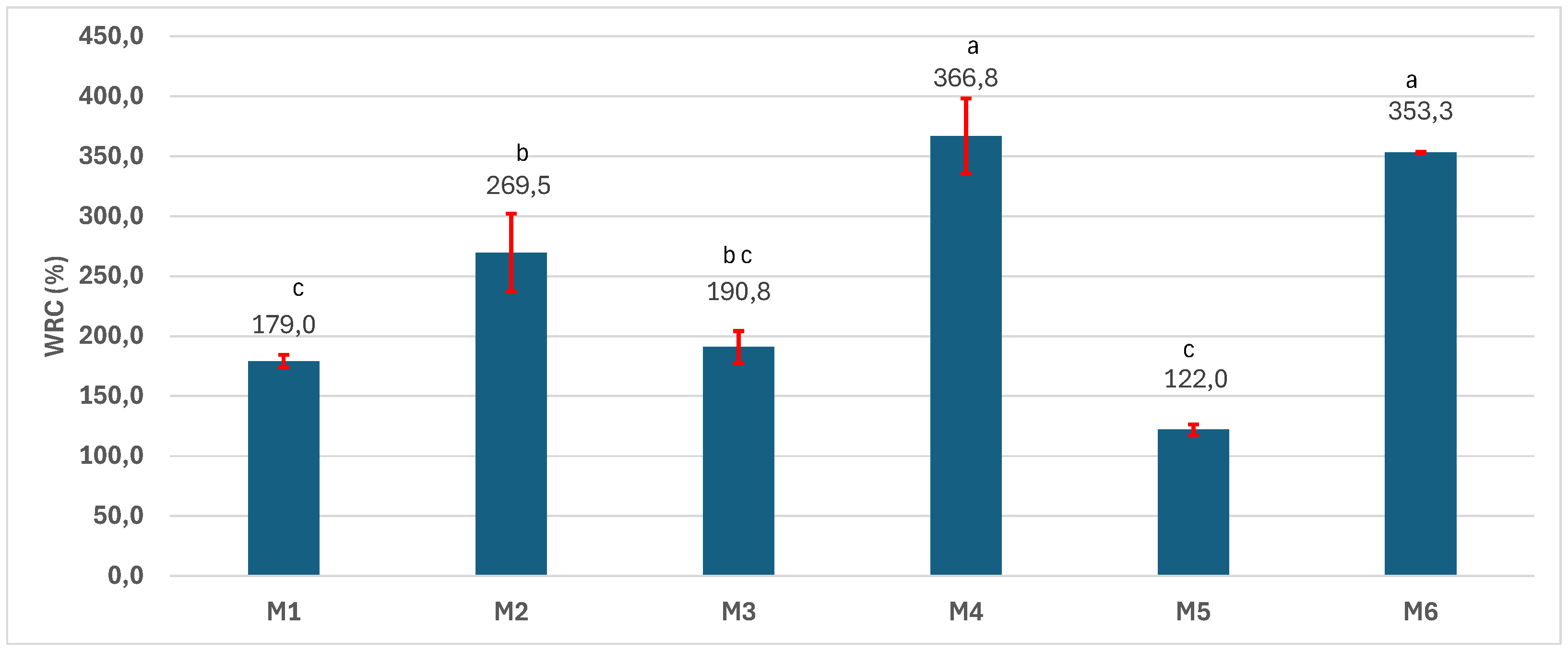

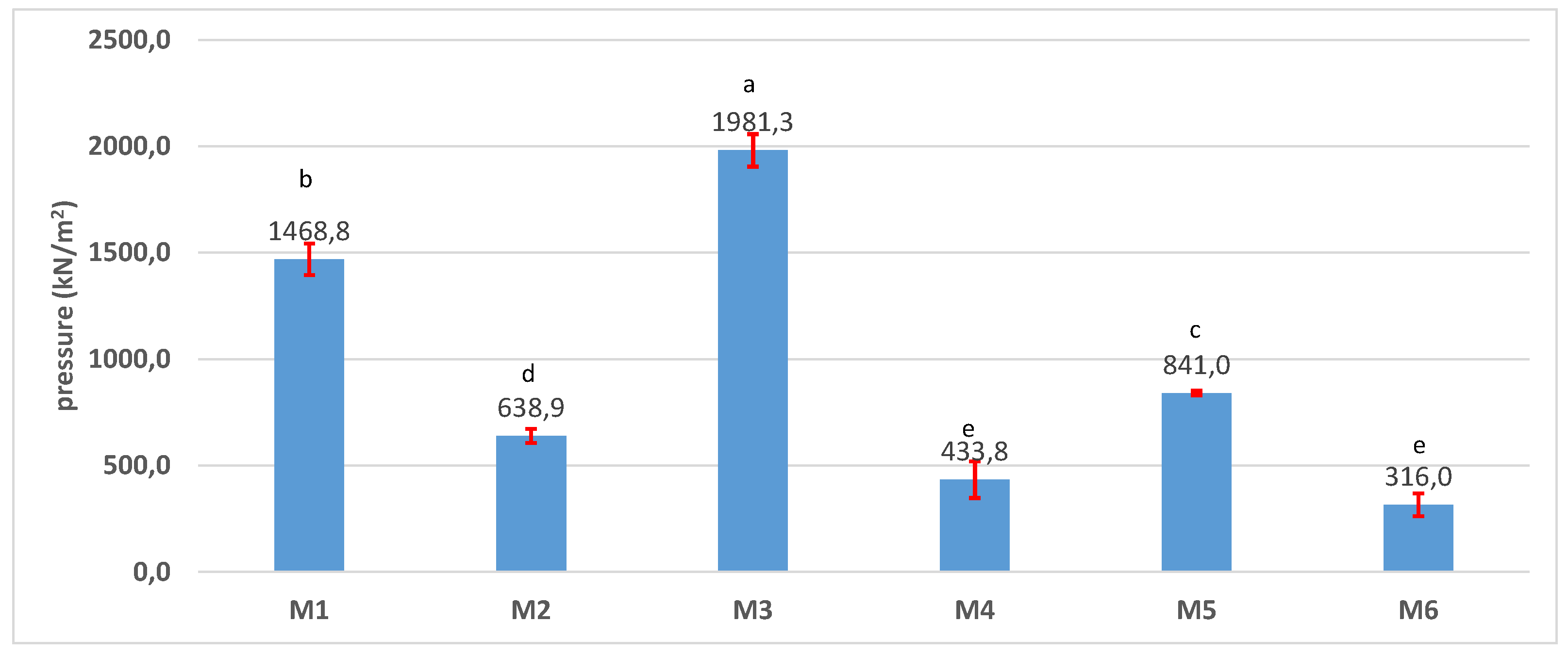

3.4. Physical-Chemical Characterization of the Scaffolds

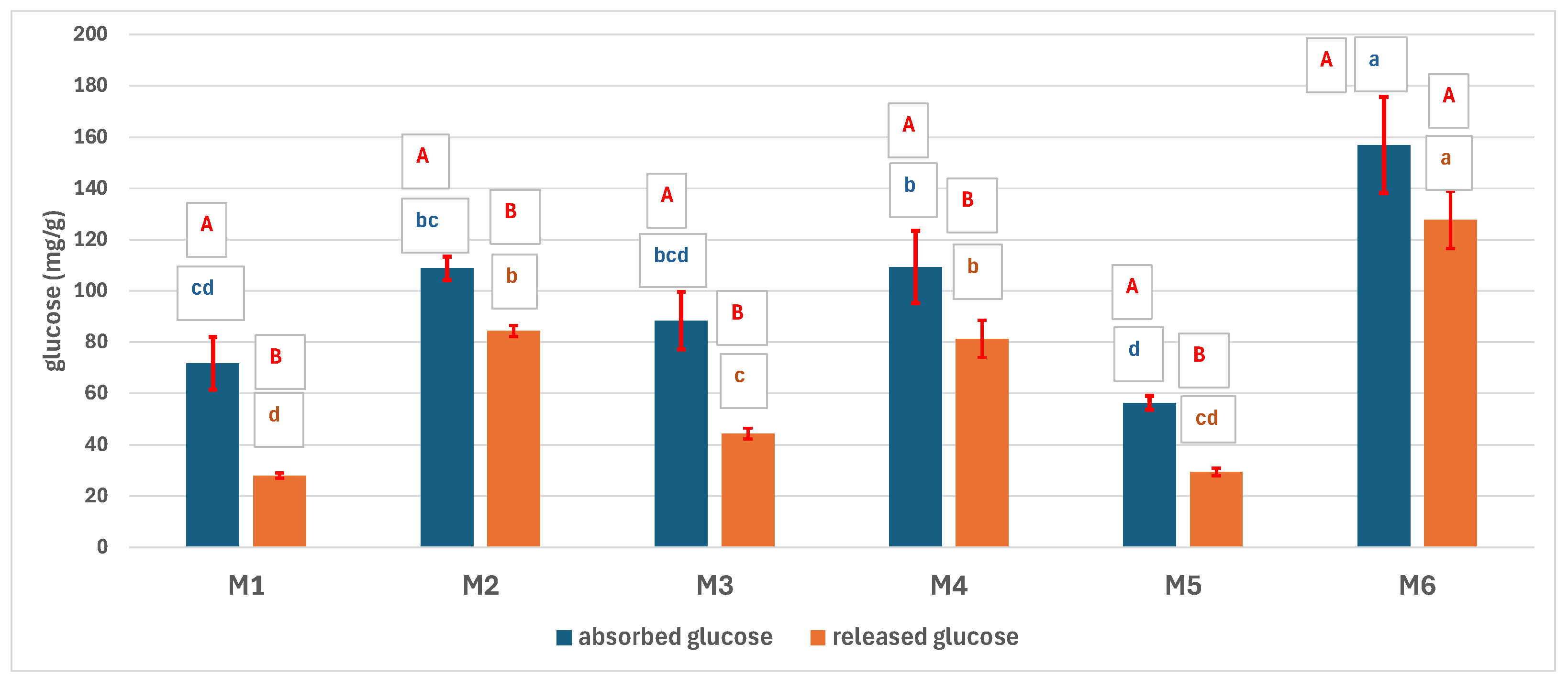

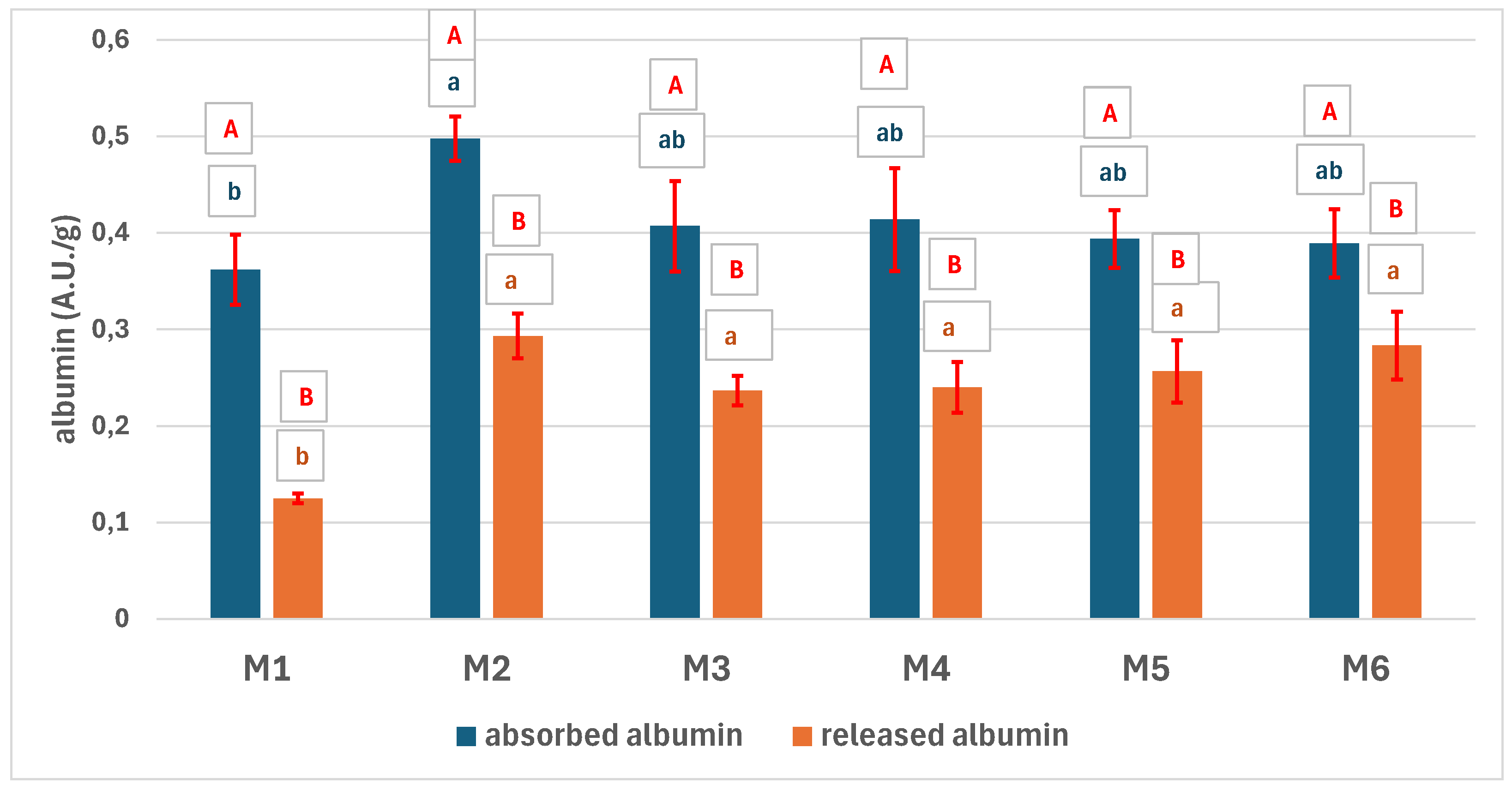

3.5. Bio-Chemical Characterization of the Scaffolds

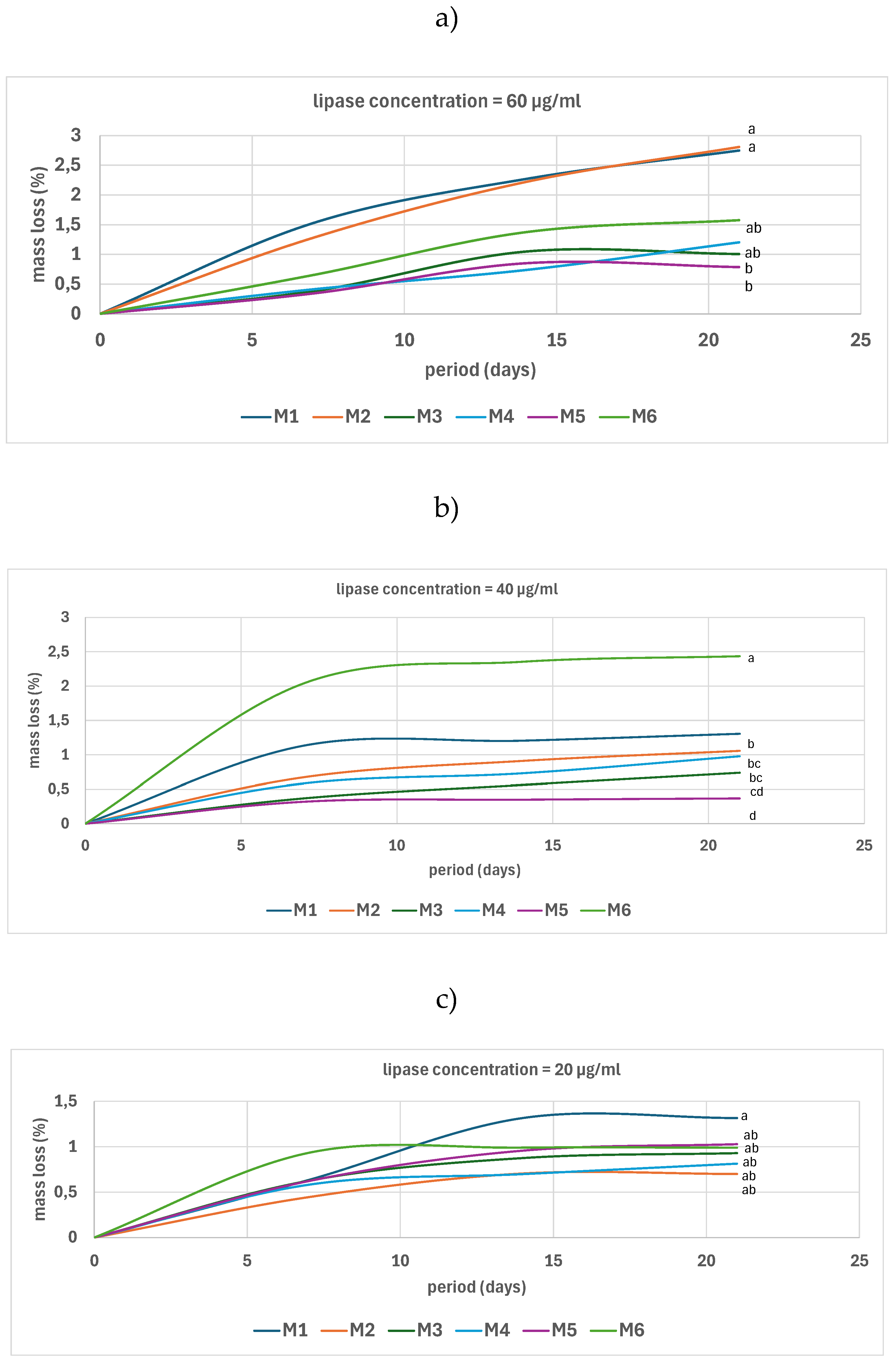

3.5.1. In Vitro Biodegradability

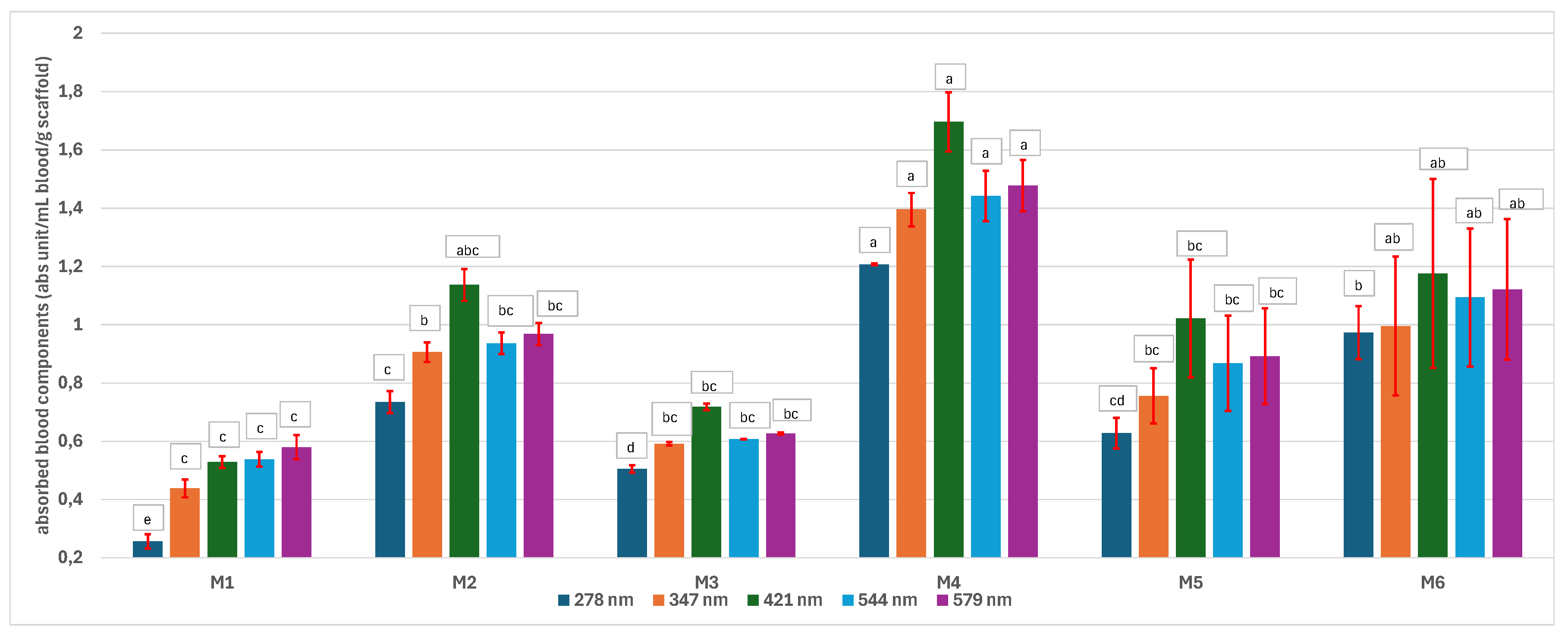

3.5.2. The Absorption of Blood Components on the Scaffolds

3.5.3. The Biocompatibility of the Scaffolds

4. Conclusions

References

- Yıldırım, S.; Demirtaş, T.T.; Dinçer, C.A.; Yıldız, N.; Karakeçili, A. Preparation of Polycaprolactone/Graphene Oxide Scaffolds: A Green Route Combining Supercritial CO2 Technology and Porogen Leaching. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2017, 133, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, C.; Liu, X.; De Isla, N.; Wang, X.; Rahouadj, R. Defining a Scaffold for Ligament Tissue Engineering: What Has Been Done, and What Still Needs to Be Done. Journal of Cellular Immunotherapy 2018, 4, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, R.; Kumar, V.; Ranjan, N.; Gupta, J.; Bhura, N. On 3D Printed Thermoresponsive PCL-PLA Nanofibers Based Architected Smart Nanoporous Scaffolds for Tissue Reconstruction. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2024, 119, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.J.; Cano, P.; Rabionet, M.; Puig, T.; Ciurana, J. 3D-Printed PCL/PLA Composite Stents: Towards a New Solution to Cardiovascular Problems. Materials 2018, 11, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitjamit, S.; Thunsiri, K.; Nakkiew, W.; Wongwichai, T.; Pothacharoen, P.; Wattanutchariya, W. The Possibility of Interlocking Nail Fabrication from FFF 3D Printing PLA/PCL/HA Composites Coated by Local Silk Fibroin for Canine Bone Fracture Treatment. Materials 2020, 13, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; He, J.; Huang, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, S.; Ji, S.; Chu, B.; Liu, W. Fetal Dermis Inspired Parallel PCL Fibers Layered PCL/COL/HA Scaffold for Dermal Regeneration. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2021, 170, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdefaramarzi, R.S.; Ebrahimian-Hosseinabadi, M.; Khodaei, M. 3D Printed Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(ε-Caprolactone)/Graphene Nanocomposite Scaffolds for Peripheral Nerve Tissue Engineering. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2024, 17, 105927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejali, A.; Ebrahimian-Hosseinabadi, M.; Kharazi, A.Z. Polyglycerol Sebacate/Polycaprolactone/Reduced Graphene Oxide Composite Scaffold for Myocardial Tissue Engineering. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uquillas, J.A.; Malik, N. Tissue Engineering, Chapter Scaffold design and fabrication, ISBN 978-0-12-824459-3 2023 Elsevier.

- Mihaly-Cozmuta, L. Statistica Experimentala, UTPress Publishing House Cluj Napoca, Romania, ISBN 978-606-737-171-0 2016 pg. 193 and 201.

- Hussain, M.; Khan, S.M.; Shafiq, M.; Al-Dossari, M.; Alqsair, U.F.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, M.I. Comparative Study of PLA Composites Reinforced with Graphene Nanoplatelets, Graphene Oxides, and Carbon Nanotubes: Mechanical and Degradation Evaluation. Energy 308, 132917. [CrossRef]

- Zain, S.K.M.; Sazali, E.S.; Ghoshal, S.K.; Hisam, R. In Vitro Bioactivity and Biocompatibility Assessment of PCL/PLA–Scaffolded Mesoporous Silicate Bioactive Glass: Role of Boron Activation. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 2023, 625, 122763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yu, J.; Liang, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Peng, S. Crystallization Behaviors Regulations and Mechanical Performances Enhancement Approaches of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Biodegradable Materials Modified by Organic Nucleating Agents. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 233, 123581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korra, S.; Madhurya, N.; Kumar, T.S.; Sainath, A.V.S.; Murthy, P.S.K.; Reddy, J.P. Extension of Shelf-Life of Mangoes Using PLA-Cardanol-Amine Functionalized Graphene Active Films. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 139849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Liu, C.; Coppola, B.; Barra, G.; Di Maio, L.; Incarnato, L.; Lafdi, K. Effect of Porosity and Crystallinity on 3D Printed PLA Properties. Polymers 2019, 11, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhameed, D.; Morsi, M.A.; Elsisi, M.E. Impact of CoCl2 on the Structural, Morphological, Optical, and Magnetic Properties of PCL/PVC Blend for Advanced Spintronic/Optoelectronic Applications. Ceramics International 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Kazarian, S.G. How Does High-Pressure CO2 Affect the Morphology of PCL/PLA Blends? Visualization of Phase Separation Using in Situ ATR-FTIR Spectroscopic Imaging. Spectrochimica Acta Part a Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2020, 243, 118760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürler, N.; Pekdemir, M.E.; Torğut, G.; Kök, M. Binary PCL–Waste Photopolymer Blends for Biodegradable Food Packaging Applications. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, 1279, 134990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Hanaor, D.A.H.; Gan, Y. Dynamic Contact Angle Hysteresis in Liquid Bridges. Colloids and Surfaces a Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2018, 555, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Ma, H.-L.; Du, Z.-H.; Yang, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.-Q. Hydrophilic and Antibacterial Modification of Poly(Lactic Acid) Films by γ-Ray Irradiation. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 21439–21445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, T.; Surianarayanan, S.; Downs, C.; Zhou, Y.; Berry, J. Nanofiber Alignment Regulates NIH3T3 Cell Orientation and Cytoskeletal Gene Expression on Electrospun PCL+Gelatin Nanofibers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Moreno-Serna, V.; Saavedra, M.; Cordoba, A.; Canales, D.; Alfaro, A.; Guzmán-Soria, A.; Orihuela, P.; Zapata, S.; Grande-Tovar, C.D.; et al. Electrospun Scaffolds Based on a PCL/Starch Blend Reinforced with CaO Nanoparticles for Bone Tissue Engineering. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 273, 132891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Fan, Z.; Huang, J.; Mao, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J. Tissue Engineering ECM-Enriched Controllable Vascularized Human Microtissue for Hair Regenerative Medicine Using a Biomimetic Developmental Approach. Journal of Advanced Research 2021, 38, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatov, F.; Zimina, A.; Chubrik, A.; Kolesnikov, E.; Permyakova, E.; Voronin, A.; Poponova, M.; Orlova, P.; Grunina, T.; Nikitin, K.; et al. Effect of Recombinant BMP-2 and Erythropoietin on Osteogenic Properties of Biomimetic PLA/PCL/HA and PHB/HA Scaffolds in Critical-Size Cranial Defects Model. Biomaterials Advances 2022, 135, 112680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, K.A.; Kulkarni, A.S.; Jankoski, P.E.; Newton, T.B.; Derbigny, B.; Clemons, T.D.; Watkins, D.L.; Morgan, S.E. Biocompatible Glycopolymer-PLA Amphiphilic Hybrid Block Copolymers with Unique Self-Assembly, Uptake, and Degradation Properties. Biomacromolecules 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hou, Z.; Chen, S.; Guo, J.; Hu, J.; Yang, L.; Cai, G. Aspergillus Oryzae Lipase-Mediated in Vitro Enzymatic Degradation of Poly (2,2′-Dimethyltrimethylene Carbonate-Co-ε-Caprolactone). Polymer Degradation and Stability 2023, 211, 110340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, S.A.; Mohammadi, M.; Saeed, M.; Haramshahi, S.M.A.; Shahmahmoudi, Z.; Pezeshki-Modaress, M. Biomimetic Fiber/Hydrogel Composite Scaffolds Based on Chitosan Hydrogel and Surface Modified PCL Chopped-Microfibers. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 278, 134936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamparelli, E.P.; Marino, M.; Scognamiglio, M.R.; D’Auria, R.; Santoro, A.; Della Porta, G. PLA/PLGA Nanocarriers Fabricated by Microfluidics-Assisted Nanoprecipitation and Loaded with Rhodamine or Gold Can Be Efficiently Used to Track Their Cellular Uptake and Distribution. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 667, 124934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahghasempour, L.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Haddadi, A.; Kabiri, M. Evaluation of Lactobacillus Plantarum and PRGF as a New Bioactive Multi-Layered Scaffold PU/PRGF/Gelatin/PU for Wound Healing. Tissue and Cell 2023, 82, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeStefano, V.; Khan, S.; Tabada, A. Applications of PLA in Modern Medicine. Engineered Regeneration 2020, 1, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Y. Preparation and Adsorption Performance of Cellulose-Graft-Polycaprolactone/Polycaprolactone Porous Material. BioResources 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadas, D.; Nagy, Z.K.; Csontos, I.; Marosi, G.; Bocz, K. Effects of Thermal Annealing and Solvent-Induced Crystallization on the Structure and Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Microfibres Produced by High-Speed Electrospinning. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2020, 142, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, A.; Verma, A.; Garg, M.; Goswami, K.; Mishra, V.; Singh, A.K.; Agrawal, G.; Murab, S. Osteogenic Citric Acid Linked Chitosan Coating of 3D-Printed PLA Scaffolds for Preventing Implant-Associated Infections. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 282, 136968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlotta, D. Literature Review of Poly(Lactic Acid). Journal of Polymer Environment 2001, 9, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasua, J.R.; Arraiza, A.L.; Balerdi, P.; Maiza, I. Crystallinity and Mechanical Properties of Optically Pure Polylactides and Their Blends. Polymer Engineering and Science 2005, 45, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample code | PLA (g) | PCL (g) | CH2Cl2 (ml) |

polymer:NaCl (wt:wt) |

NaCl (g) |

Image | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 9 | - | 51 | 1:8 | 72 |  |

||||||

| M2 | 9 | - | 51 | 1:16 | 144 |  |

||||||

| M3 | - | 9 | 51 | 1:8 | 72 |  |

||||||

| M4 | - | 9 | 51 | 1:16 | 144 |  |

||||||

| M5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 51 | 1:8 | 72 |  |

||||||

| M6 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 51 | 1:16 | 144 |  |

||||||

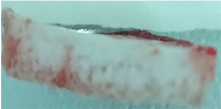

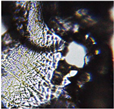

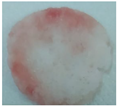

| Washing status of the scaffolds | ||||||||||||

| After the first day of washing |  |

Incomplete washing |  |

Complete washing |  |

|||||||

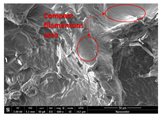

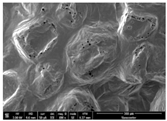

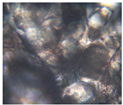

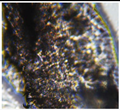

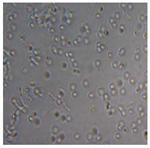

| Sample code | Microscopic image (mag 10X) |

SEM image |

|---|---|---|

| M1 |  |

|

| M2 |  |

|

| M3 |  |

|

| M4 |  |

|

| M5 |  |

|

| M6 |  |

|

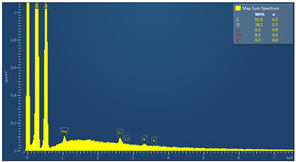

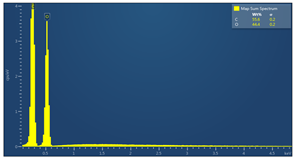

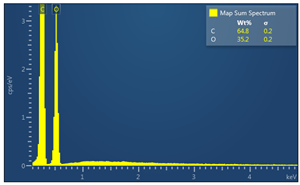

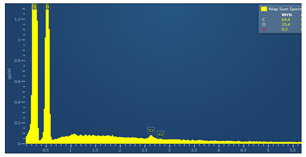

| Sample code | Map sum spectrum |

|---|---|

| M1 |  |

| M2 |  |

| M3 |  |

| M4 |  |

| M5 |  |

| M6 |  |

| Sample code | DTA events | TG mass loss | Total mass loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Exo 63°C glass transition Endo 152°C melting |

- | -99.0% |

| - | |||

| Endo 353°C decomposition | 273-315°C: -8,0% | ||

| 315-380°C: -91% | |||

| M2 | Exo 77°C glass transition Endo 154°C melting |

- | -98.2% |

| - | |||

| Endo 347°C decomposition | 275-315°C: -8.9% | ||

| 315-380°C: -89.3% | |||

| M3 | Endo 75°C melting PCL | - | -99.2% |

| Endo 402°C decomposition | 310-370°C: -8.6% | ||

| 370-426°C: -84.9% | |||

| Exo 455°C combustion/degradation | 426-500°C: -4.7% | ||

| M4 | Endo 72°C melting PCL | - | -99.1% |

| Endo 400°C degradation | 315-380°C: -19.1% | ||

| 380-427°C: -78% | |||

| Exo 453°C combustion/degradation | 427-500°C: -2% | ||

| M5 | Endo 72°C melting PCL Endo 153°C melting PLA |

- | -98.3% |

| - | |||

| Endo 352°C decomposition of PLA Endo 398°C decomposition of PCL |

270-315°C: -4.9% | ||

| 315-380°C: -38.6% | |||

| 380-420°C: -50.8% | |||

| Exo 430°C combustion | 420-500°C: -4% | ||

| M6 | Endo 71°C melting PCL Endo 154°C melting PLA |

- | -98.4% |

| - | |||

| Endo 344°C decomposition PLA Endo 396°C decomposition PCL |

270-315°C: -6.4% | ||

| 315-350°C: -33.3% | |||

| 350-420°C: -57.9% | |||

| Exo 436°C combustion/degradation | 420-500°C: -1.8% |

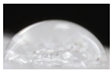

| Sample code | Replicate 1 | Replicate 2 | Replicate 3 | Average contact angle * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 |  |

|

|

54.1±6.5 a |

| M2 |  |

|

|

53.6±7.9 a |

| M3 |  |

|

|

62.3±5.3 a |

| M4 |  |

|

|

63.8±17.8 a |

| M5 |  |

|

|

55.2±5.6 a |

| M6 |  |

|

|

60.3±5.8 a |

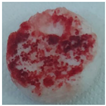

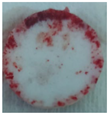

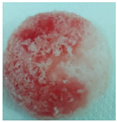

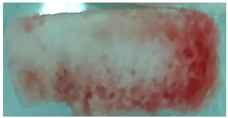

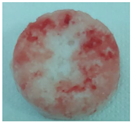

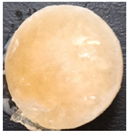

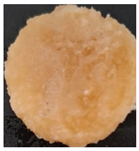

| Sample code | Macroscopic images | Microscopic images (10X) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Front view | Section view | ||

| M1 |  |

|

|

| M2 |  |

|

|

| M3 |  |

|

|

| M4 |  |

|

|

| M5 |  |

|

|

| M6 |  |

|

|

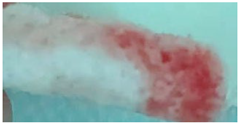

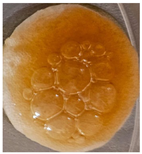

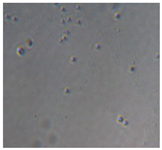

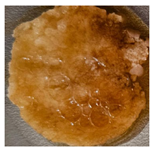

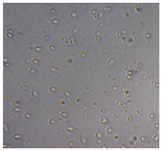

| Sample code | After 2 days | After 5 days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macroscopic image | Microscopic image of the Lactobacillus cell from the scaffold surface | ||

| M1 |  |

|

|

| M2 |  |

|

|

| M3 |  |

|

|

| M4 |  |

|

|

| M5 |  |

|

|

| M6 |  |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).