1. Introduction

As of today, there are intensive and competitive efforts from different research groups all over the world to develop new types of novel scaffolds in bone tissue engineering, as it is extensively discussed and illustrated in some recent review papers [

1,

2].

It is well known that the optimally designed scaffolds can be a promising material to accelerate bone healing, providing the most optimim environment for bone cell attachment and growth inducing new bone formation. This is the reason why the enhanced bioactivity is required from the implants. Scaffolding acts as a supportive framework for the cultivation of cells in a controlled environment, with additional cell stimulation promoting the formation of a matrix necessary for constructing a tissue base for transplant purposes. Recent progress in tissue engineering includes the formulation of novel biomaterials designed to suit particular local environments and clinical needs [

3,

4]. These scaffold materials can be prepared and utilized in a very various way, which can determine their mechanical and chemical characteristic, their surface area, porosity, micro- and nano-structure thus affecting their biological performance [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

One of the best ways to increase the biocompatibility/bioactivity of these biopolymer-based scaffolds is a calcium phosphate phase incorporation as filler material. It is common knowledge that calcium phosphates (in particular the hydroxyapatite phase) are the main mineral constituents of the natural bones, they can greatly assist in bone cell attachment and growth. By utilizing targeted preparation conditions and the correct quantity of biomineral supplements, the chemical properties and biological efficacy of these scaffolds can be effectively tailored to meet the stringent standards necessary for biomedical uses [

11,

12,

13].

The primary idea of applying novel biodegradable biocomposite scaffolds is that they can serve as an intermediary surface that enhances the adhesion, growth, and proliferation of bone cells, along with promoting the formation of new bone tissue. Once the bones are healed, the degradation of scaffolds occurring in the body is considered favorable from both a clinical and biomedical viewpoint. The dissolution rate of the scaffolds can be tailored by embedding the calcium phosphate particles within appropriately selected biopolymer materials. Our thorough investigation and review of existing literature indicate that cellulose acetate (CA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) are the most appropriate scaffold materials for medium to long-term applications. A crucial consideration is that the composite scaffolds made from bioceramics and biopolymers break down into harmless by-products, which the body can fully eliminate after the process of ossification [

14,

15,

16]. The PCL is an FDA-approved biocompatible synthetic polymer with moderate biodegradability in biological environments [

17]. It consists of serial connected hexanoate units and has a polar ester group and five non-polar methylene groups resulting in a slight amphiphilic nature besides its intrinsic hydrophobicity [

18,

19]. Contrarily, cellulose acetate is a natural, biocompatible as well as biodegradable polymer. Practically, it is the acetate ester of cellulose [

20]. CA possesses many specific properties that are advantageous in various applications, such as in drug delivery systems, in scaffolds, in medical coatings, in filtration (such as membrane filters), and last but not least, in food packaging [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Embedding calcium phosphate particles and other bioactive materials into the base polymer matrix has a great effect on the morphology and structure of the composites thus affecting their biodegradable potential. In our work, amorphous-nanocrystalline calcium phosphate phases were obtained by chemical precipitation from organic calcium and phosphorus sources and a post-treatment method was also used to obtain an optimal biomineralized CP phase that contains the necessary trace elements (Mg, Zn) in an optimized concentration. There is abundant research and review papers detailing the usefulness and benefits of the presence of these essential trace elements within the calcium phosphate matrix [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. As a novelty, we have thoroughly compared the two types of composites (natural and synthetic based) and evaluated the morphological changes that the ceramic powder addition caused in the structure of base polymer films, which have not yet been reported in the scientific literature in such detail. We have also performed immersion tests in saline solution to its effect on the microstructure and sample mass over time, reflecting their chemical stability.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphological Assessment of the Amorphous Apatite, Biomineralized Apatite, and the Two Types of Composites

2.1.1. Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis

The shapes and sizes of the particles within the pure apatite and the biomineralized apatite were compared as well as their incorporation into the cellulose acetate and the PCL matrices studied.

As

Figure 1 reveals, the CP powder prepared by the wet chemical method from the organic gluconate salt of calcium consists of very small, randomly oriented needle-like particles that form larger, flower-like agglomerations and rounded blocks at some spots. The length of the needle-like particles is around 100-150 nm, but not longer than 200 nm (

Figure 1 a). On the other hand, the organic Mg and Zn bioactive components added powder has even smaller and densely packed, very thin, thorn-like particles with a seemingly lower number of agglomerates (

Figure 1 b). This little change in morphology can be attributed to the mineral incorporation into the structure. Moreover, these kinds of needle- or thorn-like structures for different calcium apatites are also discussed in other research works [

32,

33,

34]. The composites demonstrate completely different structures. The surface of samples contains many small holes and indentations in the cases of both types of polymers. They have mainly shapeless formations with embedded small particles in the base matrix.

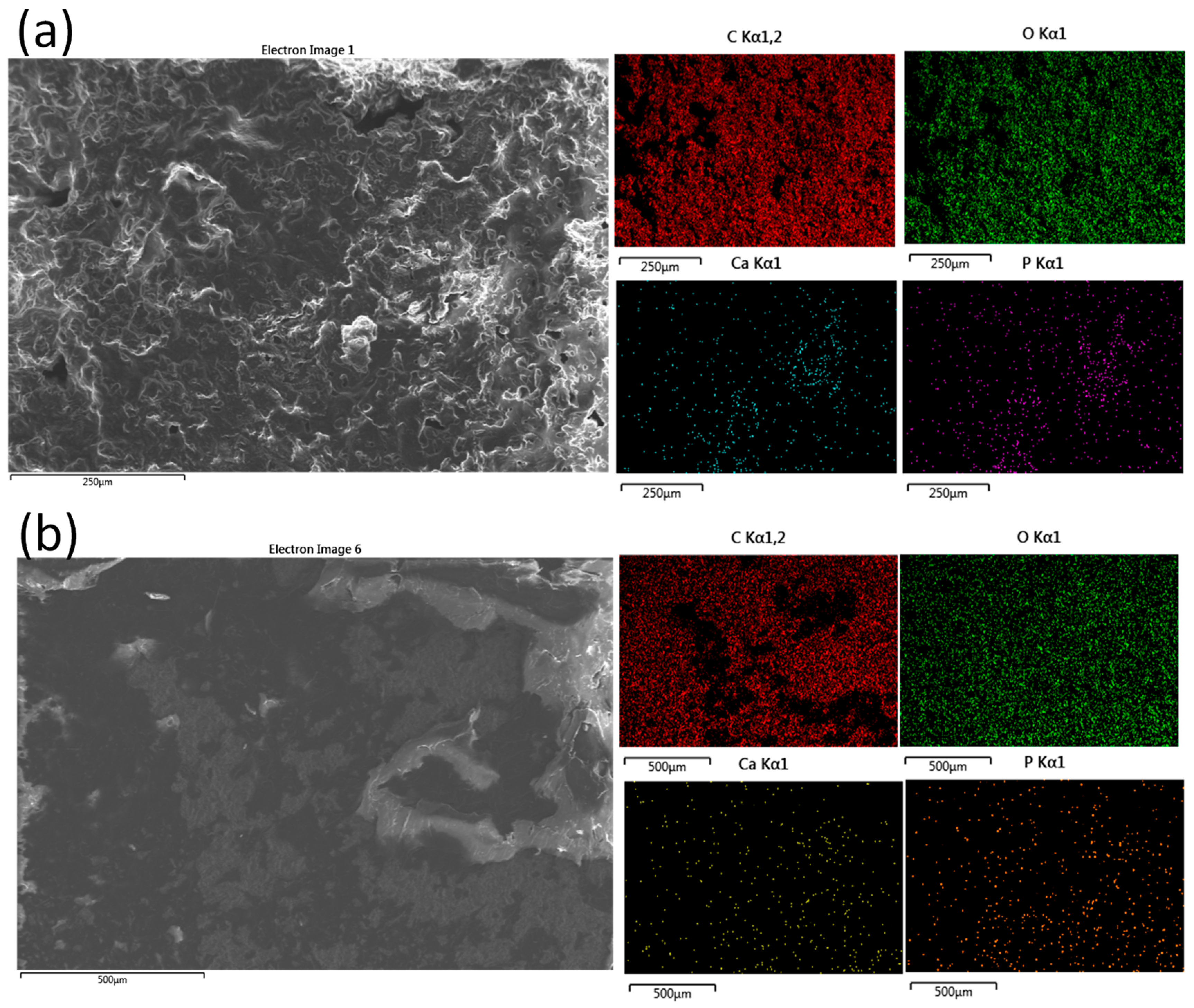

Elemental mapping was performed to check the bioactive elements’ incorporation and distribution in the calcium apatite phase, as shown in

Figure 2.

As

Figure 2 illustrates, all the doping elements are successfully incorporated into the pure CP matrix. It is also visible that the Mg and Zn element distribution within the investigated area is quite homogeneous and the quantity of Zn element is lower following the preparation parameters.

Additionally, we have also scanned the bioactive mCP powder distribution within the polymer matrices (

Figure 3) at lower magnification, covering a larger surface area.

The performed elemental mapping clearly proves the distribution characteristics of the mCP particles. The dispersion of the biomineralized apatite powder is even in both cases; the Ca and P signals are visible in the whole investigated area. However, in the case of PCL polymer, the signals are stronger and denser at some places, which shows their aggregation tendency or the imperfect mixing during the composite preparation. In these samples, the Mg and Zn signals were below the detection limit.

Since the elemental concentration provided by the EDS method is inaccurate, we carried out ICP-AES measurements. The resulting elemental composition and Ca/P ratios of apatite samples can be seen in

Table 1.

As can be seen in

Table 1, the pure CP sample has a Ca/P elemental ratio of around 1.845, which is higher compared to the value in the hydroxyapatite phase. This can imply that the powder is a specific amorphous calcium apatite that has been reported elsewhere [

35,

36,

37,

38]. In the case of mCP, the Ca percentage decreased a little because of the Mg and Zn component addition. The measured percentages reflect sufficiently the elemental ratios applied during the wet chemical precipitation since the Mg and Zn are present in the mCP powder in similar rations. The calculated Ca/P ratio was around 1.649 which is close to the reported elemental ratio in the hydroxyapatite phase, however, when we take into account the other doping elements, the (Ca+Mg+Zn)/P ratio changes to 2.154. The Mg and Zn elements are reportedly enable to incorporate into the calcium phosphate phases thus making the apatite more similar to the natural bones. It is also described, that the Ca to P ratio in human bones can vary between a wide range of around 1.7-2.33, depending on the research work and group [

39,

40]. Comparable broad calcium to phosphorus molar ratios have been reported in the cases of different ion-doped apatites. In a recent research work, Unosson et al. [

39] prepared amorphous calcium magnesium fluoride phosphate particles that are usable in preventive dentistry. The particles were prepared by co-precipitation and their amorphous feature originated from substituting Mg

2+ for Ca

2+, which impedes the nucleation and growth process of hydroxyapatite crystals. In this case, the Ca/P ratios varied between 1.2 and 2.0, while the Mg content was around 7 Wt.% in the CaP samples. There is another interesting report [

40] on the preparation of Mg and Zn added calcium phosphate material where an amorphous calcium phosphate phase co-doped with Mg and Zn elements was chemically precipitated and transformed into Mg, Zn β-tricalcium phosphate phase by calcination. In this case, the Mg content (in mol%) changed from 5.86 to 8.09, the Zn concentration varied between 0.71 and 2.81, while the calculated (Ca

2+ - Mg

2+ - Zn

2+)/P molar ratio was between 1.47 and 1.56, according to the chemical analyses.

As it is also widely discussed in the scientific literature, the Mg incorporation into the CaP phase can result in a new phase formation, which is the whitlockite (Ca18Mg2(HPO4)2(PO4)12) [

41], whilst the Zn incorporation can form parascholzite phase (CaZn2(PO4)2⋅2(H2O)) [

42].

2.1.2. Structural Analyses of CP and mCP Powders and Their Composites with PCL and cA Polymers by XRD Measurements

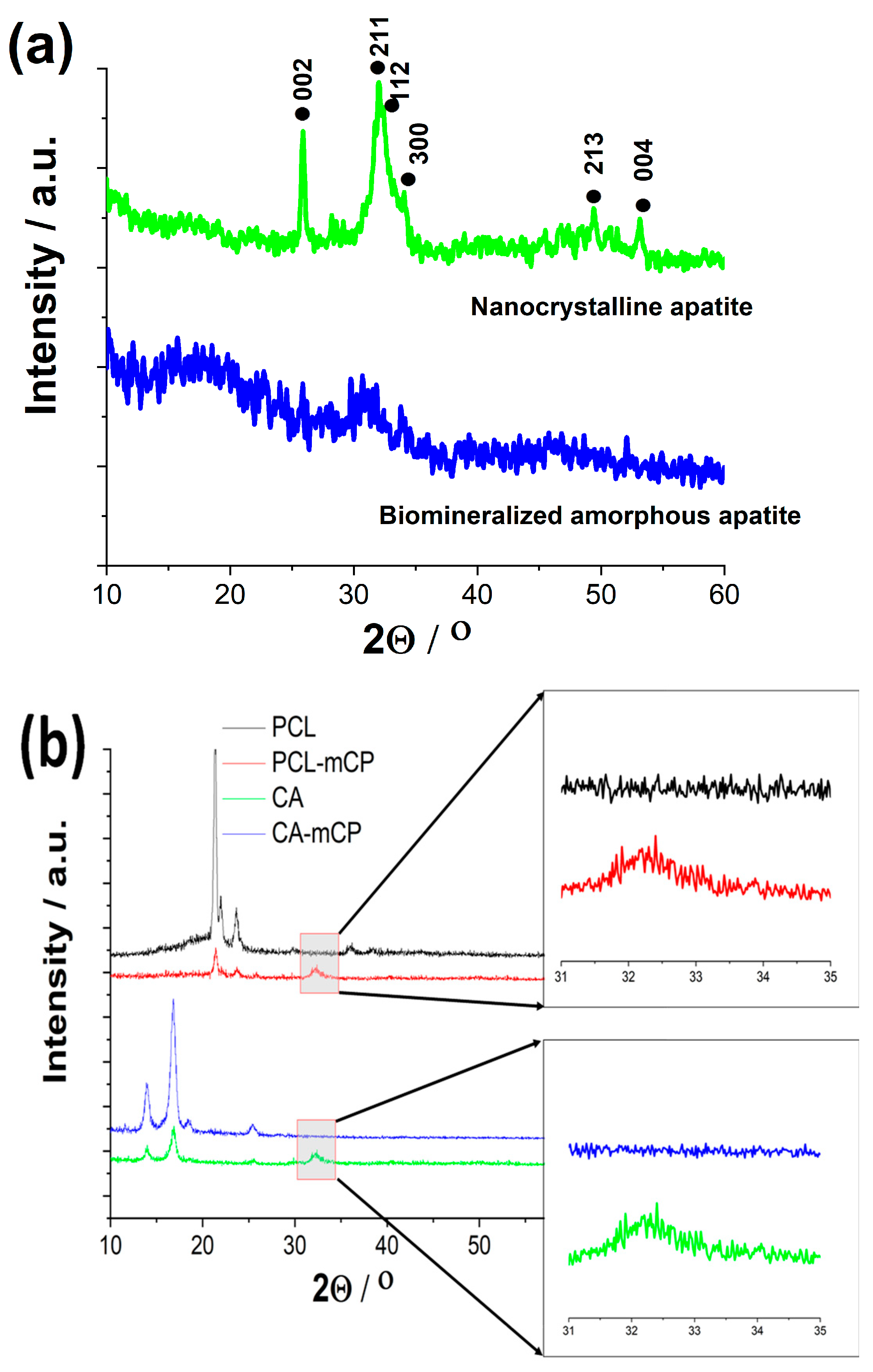

XRD measurements have been performed to determine the phase compositions of CP and biomineralized CP powders and their composites with a naturally derived polymer, such as CA, and a synthetic biopolymer, such as PCL (see

Figure 4).

The XRD pattern of the pure CP powder, prepared from organic Ca-gluconate salt, clearly shows the broadened and merged characteristic peaks of nanocrystalline or amorphous apatite with the triple-peak of hydroxyapatite crystal at 2Θ = 31.7°, 32.2° and 32.9° as well as other minor peaks at around 49° and 53°,

corresponding to Bragg’s reflection planes 213, and 004, respectively (JCPDS 01-086-1199). This pattern was also reported in other research works [

43,

44] as a nanocrystalline apatite. It is also visible that the biomineralization process, namely the organic magnesium and zinc component addition to the base CP powder in a relatively low concentration altered the micro- and nano-structure of the resulting powder. The XRD spectrum in this case a noisy line, with a very small and wide peak emergence at 2Θ from 30 to 33 region, which indicates that the powder in this case contains a very small, nano-sized or even amorphous structure with a random crystal orientation [

45,

46].

The XRD patterns of the PCL as well as the PCL-mCP composite show the characteristic peaks at 2Θ of 21.3° and 23.6° that correspond to the PCL according to JCPDS file no. 96-720-5590. The pattern of PCL-mCP exhibits noticeably broadened and weak peaks compared to the pattern of pure PCL, and in addition, there are extra merged peaks between 2Θ of 31° and 33° that can be linked to the amorphous apatite (enlarged areas in

Figure 4b). This result is well aligned with other works that investigate calcium phosphate-containing PCL composites [

47]. For example, Garcia et al. [

48] prepared polycaprolactone/calcium phosphates hybrid scaffolds that contained plant extracts with a 3D printing method and proved the incorporation of the CP particles into the polymer matrix and they observed homogeneous distribution of calcium and phosphorus within the filaments. On the other hand, Comini et al. [

49] produced a novel poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL)-based calcium phosphate composites containing silver particles that can be used as bone scaffolds. In their case, the XRD patterns of the composite scaffolds distinctly revealed the unique peaks associated with hydroxyapatite (HA) and beta-tricalcium phosphate, in addition to those of PCL.

The pattern of the cellulose acetate sample has the main characteristic peaks at around 14°, 16.7°, 18.5°, and 25.5°, which are the main characteristic peaks of cellulose acetate according to other research works [

50]. The CA-mCP composite sample presents a lower degree of crystallinity than the pure CA sample with widened peaks and lower intensity, similar to the PCL-mCP sample. The extra peaks related to the apatite are also visible in the 31° - 33° 2 theta region (also in

Figure 4 b).

2.1.3. Short-Term Immersion Measurements

We have monitored the changes in both morphology and weight of composites over a short-term (two weeks) period of immersion to check the biodegradability capacity of composite samples and to gain insight into the morphological change caused by the soaking procedure in general. In addition, we measured the concentrations of the dissolved calcium, magnesium, zinc, and phosphorous ions by ICP-AES in different time intervals.

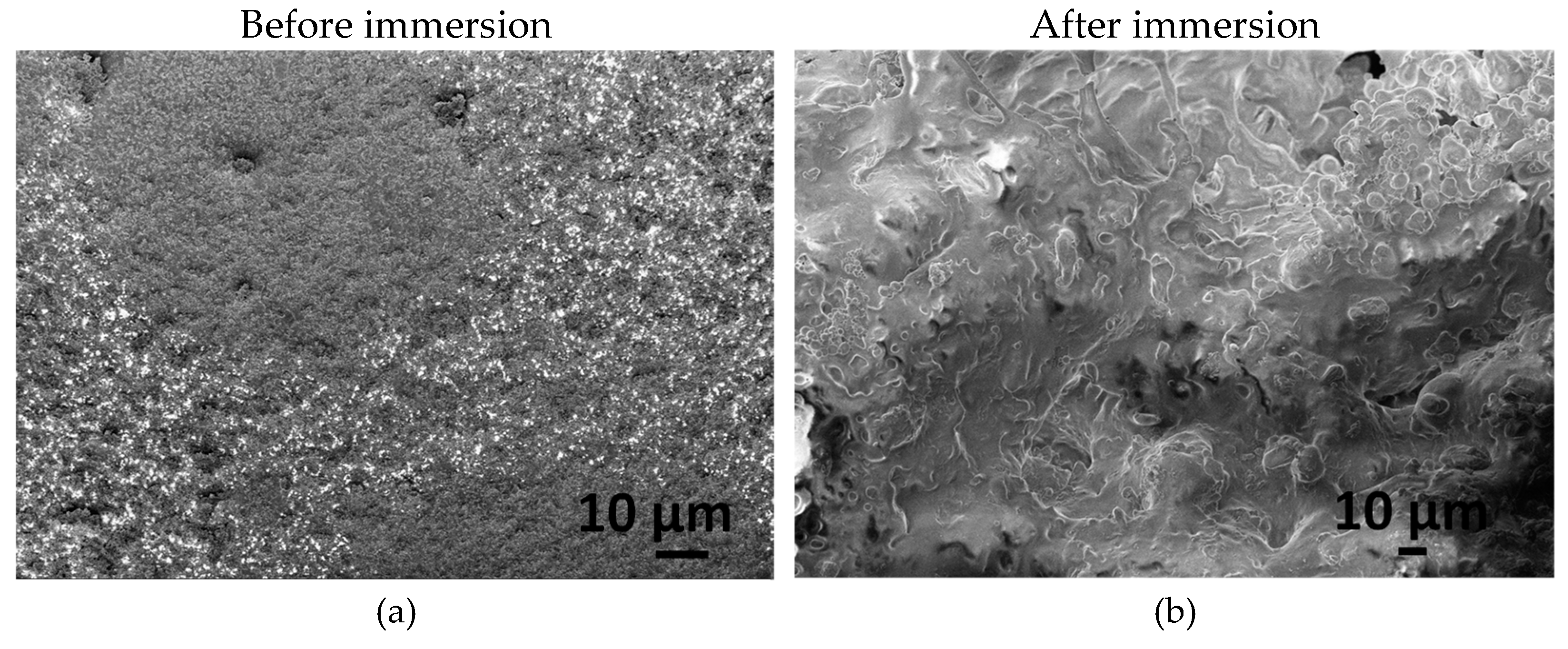

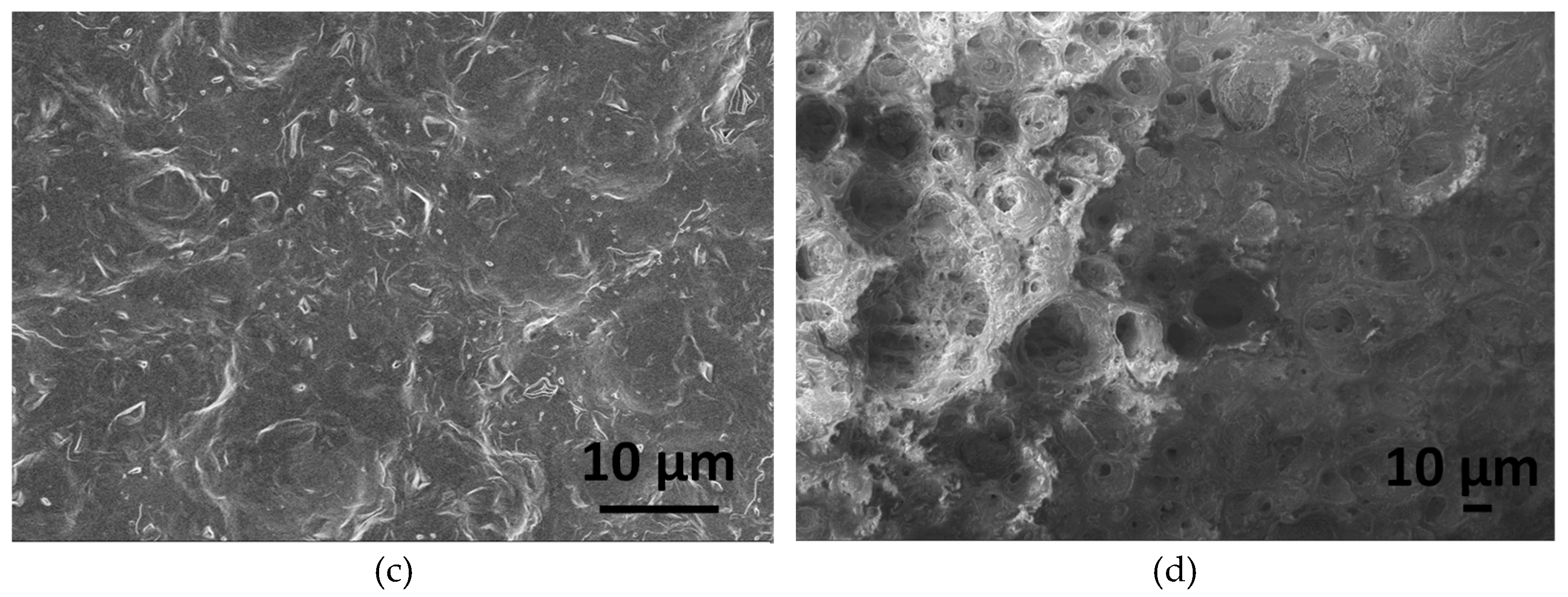

Figure 5 illustrates the morphology of CA-mCP and the PCL-mCP samples as prepared and after two weeks of immersion in saline solution.

The differences in morphology before and after immersion in saline are noticeable for both CA- and PCL-based composites. The start of degradation of both polymer composites can be detected by observing how the morphology changes during the immersion period. After immersion, the shapes of the polymer particles became poorly outlined, resulting in a fused shapeless structure that surrounds the mCP granulates. The number of pores increased after soaking and they became larger. This larger porous structure is more outstanding in the case of PCL-mCP composite. Generally, both types of polymers’ decomposition happen faster than the CP phase dissolution, since the calcium phosphate materials intrinsically possess a lower degradation rate which means lower solubility.

Numerous studies in scientific publications have explored the dissolution and degradation characteristics of both CA [

51,

52,

53] and PCL polymers [

54,

55], as well as their composites with bioceramics in biological environments [

56,

57,

58] that support and reflect our results.

We also monitored the possible weight changes in samples immersed in the saline solution.

As

Figure 6 reveals, the weight change of the PCL-mCP sample is almost negligible, it only decreases by 0.5 percent over the short-time immersion period, remaining almost constant within the margin of error, which proves its moderate degradability. This characteristic of the PCL polymer was described elsewhere [

59], stating that the PCL degradation might occur from a few months to several years depending on its molecular weight, crystallinity rate, porosity, micro-, and nanostructure as well as the polymer thickness, and the environment [

60,

61]. On the other hand, the CA-based composite showed a very slight increase in weight but this increasing tendency changed after one week of immersion. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that the nature of cellulose acetate is hydrophilic and easily can adsorb and bind water molecules and or mineral salts within its structure even in a dried state. This result is in accordance with the reported findings in the scientific literature [

20,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]

Figure 6.

Sample weight changes during the two-week immersion period in saline solution at room temperature. Values are graphed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Figure 6.

Sample weight changes during the two-week immersion period in saline solution at room temperature. Values are graphed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Figure 7.

Cumulative concentrations of the dissolved bioactive ions from CA-mCP (a) and PCL-mCP (b) composites soaked in saline solution at room temperature. The values are normalized to the unit area of samples. All data points are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

Figure 7.

Cumulative concentrations of the dissolved bioactive ions from CA-mCP (a) and PCL-mCP (b) composites soaked in saline solution at room temperature. The values are normalized to the unit area of samples. All data points are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3).

The ion release curves of both polymer composites show a similar pattern, such as the calcium and phosphorus concentrations are higher at each time point which is due to their higher amount in the composite materials. The measured concentrations of Mg and Zn ions are around 10 times lower and show a slight and gradual increasing tendency over time. On the other hand, the phosphorous concentration demonstrates a saturation curve which means a fast increase in values at the early stage of immersion then reaches a saturated state owing to the possible dissolution/precipitation processes when insoluble phosphate precipitate forms. The calcium ion has almost similar curve feature (a semi-saturation curve), which can imply mainly calcium phosphate phase precipitates, however, after around one week of immersion they start to increase again in the cases of both CA and PCL matrices. This tendency has also been observed in other research works regarding ion-loaded bioceramics [

68,

69,

70]. It is also mentionable that the measured ion concentrations are systematically higher for the CA-based composites owing to the base polymer’s unique chemical characteristics and hydrophilicity.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Different Calcium Phosphate Nano-Powders

The previously optimized calcium phosphate phase was prepared by wet precipitation method, dissolving calcium gluconate (C

12H

22O

14Ca, Molar Chemicals Ltd. - ≥99.0%) and disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na

2HPO

4, VWR International Ltd. - 99%, AnalaR NORMAPUR) as it is described in our previous paper [

30]. The pH of the suspension was adjusted to 11 with 50 g/L sodium hydroxide (NaOH, VWR International Ltd. - ≥99.5% ACS, at a pH value of 11) for 24 hours to promote the apatite formation. After the apatite formation was completed, bioactive substances were added to the suspension in calculated concentrations. The bioactive materials were organic magnesium gluconate (C

12H

22O

14Mg, Molar Chemicals Ltd. - ≥99.0%) and zinc gluconate (C

12H

22O

14Zn, Molar Chemicals Ltd. - ≥99.0%) salts that are all extensively used as nutritional supplements to treat magnesium and zinc deficiency in patients. The calculated Ca/Mg/Zn elemental weight ratio was 1/0.2/0.1. Finally, the powders were collected and used for further characterization and composite preparation.

4.2. Preparation of mCP-PCL and mCP-CA Composite Scaffolds

For the PCL-based composite preparation, (Polycaprolactone, average Mw ~1,300,000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA)) the concentration of the polymer solution was 10% (w/v) in dichloromethane (DCM) solvent. The composite was formed by adding freshly prepared mCP particles into the polymer solution in 0.2g/10mL concentration under vigorous stirring.

The same preparation parameters were applied in the case of CA (cellulose acetate average Mw ≈100,000, Acros Organics, Geel, Antwerp, Belgium, acetyl content 39.8%) biopolymer but the applied solvent was acetone. The composite concentration was similarly 0.2g mCP in a 10 ml polymer solution. The final suspensions in both cases were poured into silicon molds (in the shape of a disc of 30 mm diameter) and left to dry under ambient conditions. The dried composite films were then collected and further characterized.

4.3. Characterization Methods

4.3.1. X-ray Diffraction Analysis

The structure of biomineralized CaP powder and composites were analyzed with an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker AXS D8 Discover with Cu Kα radiation source, λ= 0.154 nm) using Göbel mirror and scintillation detector (Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany). The operation parameters were at 40kV and 40 mA. The diffraction patterns were collected from 10° to 65° 2θ range with 0.3°/min steps and 0.02° step size. Diffrac.Eva software was used to evaluate the measured XRD patterns and to detect the potential crystallite phases.

4.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphological properties of calcium phosphate powders as well as the pure and bioceramic loaded PVP and CA fibres were examined by field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Thermo Scientific, Scios2, Waltham, MA, US) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry (Oxford Instrument EDS detector X-Maxn, Abingdon, UK). Map sum spectrum was recorded on samples using 6 keV accelerating voltage.

4.3.3. Short-Term Immersion Tests

The bioresorbable characteristics of CA-mCP and PCL-mCP composite samples were studied by a simple immersion test. All the samples were soaked in saline solution (0.9% NaCl solution). The samples’ size was 30mmx1mm discs. The working surface area (in connection with liquid during immersion) of all composites was set to 15 cm2. During the soaking procedure, the composite samples were immersed in 10 mL saline solution in separate containers at room temperature for two weeks. The purpose of this test was to follow the quantitative change in the mass of the composite during soaking as well as the qualitative change in the morphology of the composite particles. The percentage of weight change was determined by the formula: W% = (Ws - Wd)/Ws X 100%; Ws is the starting weight of the sample and Wd is the weight of the dried samples after different set times of soaking (0, 1, 7 and 14 days). The samples were taken out at the above-pointed intervals, washed repeatedly with distilled water, and dried to a constant weight

4.3.4. ICP-AES Measurements

To determine the exact elemental ratio in CP and mCP powders and to check the possible dissolution of different ions (Ca2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+) from the composites, an inductively coupled plasma–atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) technique with ICP-AES spectrometer (Spectro, Spectro Arcos) was utilized. The measurement was carried out in a cyclone fog chamber in the presence of an internal standard (1 ppm Y). Four-point calibration was applied, and standard solutions in concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 ppm were recorded for each element. The CP and mCP powders were dissolved in 10 mL 1 N HCl solution to determine the elemental composition.

To assess the short-term dissolving characteristics of both composite types, samples (with a particular working area of 10 cm2) were immersed in 5 mL of saline solution. Samples were collected from the supernatant at different time intervals: 0, 1, 7, 14 days. The concentrations of Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+ ions were measured.

5. Conclusions

Biomineralized and nanocrystalline CP powders were successfully prepared by the wet chemical method from the organic gluconate salt of calcium. The prepared powder consists of very small, randomly oriented needle-like particles with some agglomerations and larger blocks. The organic Mg and Zn bioactive components addition caused a change in the morphology, the particles became smaller and more densely packed with a lower number of agglomerates.

The XRD measurements also have proven the CP powder to be nanocrystalline or quasi-amorphous, while the mCP powder to be completely amorphous showing only widely broadened and small characteristic peaks. The mCP powder contained the Mg and Zn trace elements in 15 Wt.% in total with a Mg: Zn ratio of around 3:1 as the ICP-AES measurement revealed.

The mCP powder addition to the base polymer solutions (both CA and PCL) also induced a noticeable change in the polymers’ microstructure. The bioceramic particles were evenly distributed into the polymer matrices, according to the SEM elemental mapping.

The short-term immersion tests confirmed the moderate degradability of both types of composites, however, their degradation characteristics were different. This can be attributed to the different physical and chemical properties of the two polymers since the cellulose acetate is hydrophilic whilst the PCL is mainly hydrophobic. Besides, the ICP measurements detected continuous and gradual ionic dissolution from the composites in both cases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.; methodology, M.F.; XRD measurements, Zs.E.H.; ICP-AES measurements, I.T.; validation, M.F., Zs.E.H.; and C.B.; investigation, M.F.; resources, M.F.; data curation, M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F.; writing—review and editing, M.F.; supervision, C.B. and K.B; project administration, M.F.; funding acquisition, M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office – NKFIH OTKA-FK 146141.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Z. Kovacs (Centre for Energy Research, Hungary) for the SEM measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alkhursani, S.A.; Ghobashy, M.M.; Al-Gahtany, S.A.; Meganid, A.S.; Abd El-Halim, S.M.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, F.S.; Atia, G.A.N.; Cavalu, S. Application of Nano-Inspired Scaffolds-Based Biopolymer Hydrogel for Bone and Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Polymers 2022, 14, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.S.B.; Ponnamma, D.; Choudhary, R.; Sadasivuni, K.K. A Comparative Review of Natural and Synthetic Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds. Polymers 2021, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifin, N.; Sudin, I.; Ngadiman, N.H.A.; Ishak, M.S.A. A Comprehensive Review of Biopolymer Fabrication in Additive Manufacturing Processing for 3D-Tissue-Engineering Scaffolds. Polymers 2022, 14, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathanael, A.J.; Oh, T.H. Encapsulation of Calcium Phosphates on Electrospun Nanofibers for Tissue Engineering Applications. Crystals 2021, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, Y. Calcium Phosphate-Based Nanomaterials: Preparation, Multifunction, and Application for Bone Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2023, 28, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, H.A.; Mabroum, H.; Lahcini, M.; Oudadesse, H.; Barroug, A.; Youcef, H.B.; Noukrati, H. Manufacturing methods, properties, and potential applications in bone tissue regeneration of hydroxyapatite-chitosan biocomposites: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 243, 125150. [Google Scholar]

- Soleymani, S.; Naghib, S.M. 3D and 4D printing hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and regeneration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushra, A.; Subhani, A.; Islam, N. A comprehensive review on biological and environmental applications of chitosan-hydroxyapatite biocomposites. Compos. Part C 2023, 12, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska-Lesniewicz, A.; Szczepanska, P.; Kaminska, M.; Nowosielska, M.; Sobczyk-Guzenda, A. 6-step manufacturing process of hydroxyapatite filler with specific properties applied for bone cement composites. Ceram Int 2022, 48, 26854–26864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Segura-Egea, J.J.; Díaz-Cuenca, A. Sol–Gel Technologies to Obtain Advanced Bioceramics for Dental Therapeutics. Molecules 2023, 28, 6967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altayyar, SS. The Essential Principles of Safety and Effectiveness for Medical Devices and the Role of Standards. Med Devices (Auckl) 2020, 13, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Ki, M.-R.; Han, Y.; Pack, S.P. Biomineral-Based Composite Materials in Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliaz, N.; Metoki, N. Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics: A Review of Their History, Structure, Properties, Coating Technologies and Biomedical Applications. Materials (Basel) 2017, 10, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Rezwan, K.; Chen, O.; Blaker, J.J.; Boccaccini, A.R. Biodegradable and Bioactive Porous Polymer/Inorganic Composite Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sobrino, R.; Muñoz, M.; Rodríguez-Jara, E.; Rams, J.; Torres, B.; Cifuentes, S.C. Bioabsorbable Composites Based on Polymeric Matrix (PLA and PCL) Reinforced with Magnesium (Mg) for Use in Bone Regeneration Therapy: Physicochemical Properties and Biological Evaluation. Polymers 2023, 15, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, J.R.A.; Souza, V.G.L.; Fuciños, P.; Pastrana, L.; Fernando, A.L. Methodologies to Assess the Biodegradability of Bio-Based Polymers—Current Knowledge and Existing Gaps. Polymers 2022, 14, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Bhattacharyya, C.; Sahu, R.; Dua, T.K.; Kandimalla, R.; Dewanjee, S. Polymeric nanotherapeutics: An emerging therapeutic approach for the management of neurodegenerative disorders. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 91, 105267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.W.; Hamad, T.I.; Haider, J. Biological properties of polycaprolactone and barium titanate composite in biomedical applications. Sci Prog 2023, 106, 368504231215942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vach Agocsova, S.; Culenova, M.; Birova, I.; Omanikova, L.; Moncmanova, B.; Danisovic, L.; Ziaran, S.; Bakos, D.; Alexy, P. Resorbable Biomaterials Used for 3D Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering: A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Hakkarainen, M. Degradable or not? Cellulose acetate as a model for complicated interplay between structure, environment and degradation. Chemosphere, 2021, 265, 128731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wsoo, M.A.; Shahir, S.; Boharia, S.P.B.; Nayan, N.H.M.; Razak, S.I.A. A review on the properties of electrospun cellulose acetate and its application in drug delivery systems: A new perspective. Carbohydrate Research, 2020, 491, 107978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cidade do Carmo, C.; Brito, M.; Oliveira, J.P.; Marques, A.; Ferreira, I.; Baptista, A.C. Cellulose Acetate and Polycaprolactone Fibre Coatings on Medical-Grade Metal Substrates for Controlled Drug Release. Polymers 2024, 16, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatanpour, V.; Pasaoglu, M.E.; Barzegar, H.; Teber, O.O.; Kaya, R.; Bastug, M.; Khataee, A.; Koyuncu, I. Cellulose acetate in fabrication of polymeric membranes: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oprea, M.; Voicu, S.I. Cellulose Acetate-Based Materials for Water Treatment in the Context of Circular Economy. Water 2023, 15, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, P.; Salem, K.S.; Hubbe, M.A.; Pal, L. Advances in barrier coatings and film technologies for achieving sustainable packaging of food products – A review. Trends in Food Sci Techn 2021, 115, 461–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalera, C.H.; Figueroa, I.A.; Casas-Luna, M.; Rodríguez-Gómez, F.J.; Piña-Barba, C.; Montufar, E.B.; Čelko, L. Magnesium Strengthening in 3D Printed TCP Scaffold Composites. J Compos Sci 2023, 7, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornelas, J.; Dornelas, G.; Rossi, A.; Piattelli, A.; Di Pietro, N.; Romasco, T.; Mourão, C.F.; Alves, G.G. The Incorporation of Zinc into Hydroxyapatite and Its Influence on the Cellular Response to Biomaterials: A Systematic Review. J Funct Biomater 2024, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G.C.; Barbaro, K.; Kuroda, P.A.B.; Imperatori, L.; De Bonis, A.; Teghil, R.; Curcio, M.; Innocenzi, E.; Grigorieva, V.Y.; Vadalà, G.; et al. Incorporation of Ca, P, Mg, and Zn Elements in Ti-30Nb-5Mo Alloy by Micro-Arc Oxidation for Biomedical Implant Applications: Surface Characterization, Cellular Growth, and Microorganisms’ Activity. Coatings 2023, 13, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Bae, J.-S.; Kim, Y.-I.; Yoo, K.-H.; Yoon, S.-Y. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Performances of Magnesium-Substituted Dicalcium Phosphate Anhydrous. Materials 2024, 17, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furko, M.; Detsch, R.; Tolnai, I.; Balázsi, K.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Balázsi, C. Biomimetic mineralized amorphous carbonated calcium phosphate-polycaprolactone bioadhesive composites as potential coatings on implant materials. Ceram Int 2023, 49, 18565–18576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, D.M.; Hamilton, J.G.; Peak, D. The Influences of Magnesium upon Calcium Phosphate Mineral Formation and Structure as Monitored by X-ray and Vibrational Spectroscopy. Soil Syst 2020, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čadež, V.; Erceg, I.; Selmani, A.; Domazet Jurašin, D.; Šegota, S.; Lyons, D.M.; Kralj, D.; Sikirić, M.D. Amorphous Calcium Phosphate Formation and Aggregation Process Revealed by Light Scattering Techniques. Crystals 2018, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Åhlén, M.; Tai, C.-W.; Bajnóczi, É.G.; de Kleijne, F.; Ferraz, N.; Persson, I.; Strømme, M.; Cheung, O. Highly Porous Amorphous Calcium Phosphate for Drug Delivery and Bio-Medical Applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheah, C.W.; Al-Namnam, N.M.; Lau, M.N.; Lim, G.S.; Raman, R.; Fairbairn, P.; Ngeow, W.C. Synthetic Material for Bone, Periodontal, and Dental Tissue Regeneration: Where Are We Now, and Where Are We Heading Next? Materials 2021, 14, 6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiropoulou, P.; Fountos, G.; Martini, N.; Koukou, V.; Michail, C.; Kandarakis, I.; Nikiforidis, G. Bone calcium/phosphorus ratio determination using dual energy X-ray method. Phys Med 2015, 31, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourkoumelis, N.; Balatsoukas, I.; Tzaphlidou, M. Ca/P concentration ratio at different sites of normal and osteoporotic rabbit bones evaluated by Auger and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. J Biol Phys 2012, 38, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzaphlidou, M.; Zaichick, V. Calcium, phosphorus, calcium-phosphorus ratio in rib bone of healthy humans. Biol Trace Elem Res 2003, 93, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, T.; Sakae, T.; Nakada, H.; Kaneda, T.; Okada, H. Confusion between Carbonate Apatite and Biological Apatite (Carbonated Hydroxyapatite) in Bone and Teeth. Minerals 2022, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unosson, E.; Feldt, D.; Xia, W.; Engqvist, H. Amorphous Calcium Magnesium Fluoride Phosphate—Novel Material for Mineralization in Preventive Dentistry. Appl Sci 2023, 13, 6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadjieva, D.; Gergulova, R.; Sezanova, K.; Kovacheva, D.; Titorenkova, R. Mg, Zn Substituted Calcium Phosphates—Thermodynamic Modeling, Biomimetic Synthesis in the Presence of Low-Weight Amino Acids and High Temperature Properties. Materials 2023, 16, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiseliene, R.; Linkaite, G.; Zarkov, A.; Kareiva, A.; Grigoraviciute, I. Large-Scale Green Synthesis of Magnesium Whitlockite from Environmentally Benign Precursor. Materials 2024, 17, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, A.A.; Abdulaziz, F.; Alyami, M.; Alotibi, S.; Sakka, S.; Mallouh, S.A.; Abu-Zurayk, R.; Alshaaer, M. The Effect of Full-Scale Exchange of Ca2+ with Zn2+ Ions on the Crystal Structure of Brushite and Its Phase Composition. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouet, C. Apatite Formation: Why It May Not Work as Planned, and How to Conclusively Identify Apatite Compounds, Hindawi Publishing Corporation. BioMed Res Int 2013, 2013, 490946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gandhi, A.A.; Zeglinski, J.; Gregor, M.; Tofail, S.A.M. A Complementary Contribution to Piezoelectricity from Bone Constituents. IEEE TDEI 2012, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, K.A.; Petzold, C.; Pluduma-LaFarge, L.; Kumermanis, M.; Haugen, H.J. Structural and Chemical Hierarchy in Hydroxyapatite Coatings. Materials 2020, 13, 4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; He, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Tan, Z. Characteristics of (002) Oriented Hydroxyapatite Coatings Deposited by Atmospheric Plasma Spraying. Coatings 2018, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, C.; Tulliani, J.M.; Tadier, S.; Meille, S.; Chevalier, J.; Palmero, P. Novel calcium phosphate/PCL graded samples: Design and development in view of biomedical applications. Mat Sci Eng C 2019, 97, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Orozco, Y.; Betancur, A.; Moreno, A.I.; Fuentes, K.; Lopera, A.; Suarez, O.; Lobo, T.; Ossa, A.; Peláez-Vargas, A.; Paucar, C. Fabrication of polycaprolactone/calcium phosphates hybrid scaffolds impregnated with plant extracts using 3D printing for potential bone regeneration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comini, S.; Sparti, R.; Coppola, B.; Mohammadi, M.; Scutera, S.; Menotti, F.; Banche, G.; Cuffini, A.M.; Palmero, P.; Allizond, V. Novel Silver-Functionalized Poly(ε-Caprolactone)/Biphasic Calcium Phosphate Scaffolds Designed to Counteract Post-Surgical Infections in Orthopedic Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, F.N.; Faria-Tisher, P.C.S.; Duarte, J.L.; Carvalho, G.M. Preparation and characterization of microporous cellulose acetate films using breath figure method by spin coating technique. Cellulose 2017, 24, 4981–4995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbruyns, L.; Van de Perre, D.; Hölter, D. Biodegradability of Cellulose Diacetate in Aqueous Environments. J Polym Environ 2024, 32, 1326–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Liang, Y.; Sun, L.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Dong, D.; Liu, H. Degradation Characteristics of Cellulose Acetate in Different Aqueous Conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.L.; Hassabo, A.G. Modified Cellulose Acetate Membrane for Industrial Water Purification. Egypt J Chem 2022, 65, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimowska, A.; Morawska, M.; Bocho-Janiszewska, A. Biodegradation of poly(ε-caprolactone) in natural water environments. Polish J Chem Techn 2017, 19, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, D.S. Solubility parameters and solvent affinities for polycaprolactone: A comparison of methods. J Appl Polym Sci 2020, 137, 48908–48920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziadek, M.; Zagrajczuk, B.; Menaszek, E.; Cholewa-Kowalska, K. A new insight into in vitro behaviour of poly(ε-caprolactone)/bioactive glass composites in biologically related fluids. J Mater Sci 2018, 53, 3939–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaght, F.E.; Azzaoui, K.; El Idrissi, A.; Jodeh, S.; Khalaf, B.; Rhazi, L.; Bellaouchi, R.; Asehraou, A.; Hammouti, B.; Sabbahi, R. Synthesis, characterization, and biodegradation studies of new cellulose-based polymers. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bading, M.; Olsson, O.; Kümmerer, K. Analysis of environmental biodegradability of cellulose-based pharmaceutical excipients in aqueous media. Chemosphere 2024, 352, 141298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevoralová, M.; Koutný, M.; Ujcic´, A.; Starý, Z.; Šerá, J.; Vlková, H.; Šlouf, M.; Fortelný, I.; Kruliš, Z. Structure Characterization and Biodegradation Rate of Poly(ε-caprolactone)/Starch Blends. Front Mater 2020, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, M.V.; Girase, A.; King, M.W. Degradation of Poly(ε-caprolactone) Resorbable Multifilament Yarn under Physiological Conditions. Polymers 2023, 15, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leja, K.; Lewandowicz, G. Polymer biodegradation and biodegradable polymers. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2010, 19, 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Fornazier, M.; Gontijo de Melo, P.; Pasquini, D.; Otaguro, H.; Pompêu, G.C.S.; Ruggiero, R. Additives Incorporated in Cellulose Acetate Membranes to Improve Its Performance as a Barrier in Periodontal Treatment. Front. Dent. Med. 2021, 2, 776887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, M.; Meybodi, S.M.; Zarei, A.; et al. Cellulose acetate nanofibrous wound dressings loaded with 1% probucol alleviate oxidative stress and promote diabetic wound healing: an in vitro and in vivo study. Cellulose 2022, 29, 5359–5374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidale, L.; Ruiz, N.; Heinze, T.; El-Seoud, O. Cellulose Swelling by Aprotic and Protic Solvents: What are the Similarities and Differences? Macromol Chem Phys 2008, 209, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villabona-Ortíz, Á.; Ortega-Toro, R.; Pedroza-Hernández, J. Biocomposite Based on Polyhydroxybutyrate and CelluloseAcetate for the Adsorption of Methylene Blue. J Compos Sci 2024, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.S.; Aguado, R.; Bértolo, R.; et al. Enhanced water absorption of tissue paper by cross-linking cellulose with poly(vinyl alcohol). Chem Pap 2022, 76, 4497–4507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sango, T.; Koubaa, A.; Ragoubi, M.; Yemele, M.C.N.; Leblanc, N. Insights into the functionalities of cellulose acetate and microcrystalline cellulose on water absorption, crystallization, and thermal degradation kinetics of a ternary polybutylene succinate-based hybrid composite. Ind Crops Prod 2024, 222, 222–119572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, A.; Cadar, O.; Frangopol, P.T.; Petean, I.; Tomoaia, G.; Paltinean, G.-A.; Racz, C.P.; Horovitz, O.; Tomoaia-Cotisel, M. Ion release from hydroxyapatite and substituted hydroxyapatites in different immersion liquids: in vitro experiments and theoretical modelling study. R Soc Open Sci 2021, 8, 201785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutthavas, P.; Schumacher, M.; Zheng, K.; Habibović, P.; Boccaccini, A.R.; van Rijt, S. Zn-Loaded and Calcium Phosphate-Coated Degradable Silica Nanoparticles Can Effectively Promote Osteogenesis in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, H.; Lallukka, M.; Miola, M.; Spriano, S.; Vernè, E.; Raineri, D.; Leigheb, M.; Ronga, M.; Cappellano, G.; Chiocchetti, A. Human T-Cell Responses to Metallic Ion-Doped Bioactive Glasses. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).