1. Introduction

Bone tissue engineering provides an effective approach for restoring bone lost or damaged due to injury, disease, or surgical procedures. A key component of this approach is the design of a porous scaffold that provides a three-dimensional environment, facilitating nutrient and oxygen delivery while promoting cell attachment, growth, and differentiation for new bone tissue formation. The ideal scaffold must be biocompatible, supporting normal cellular processes without causing toxicity. It should also be biodegradable, maintain adequate mechanical strength, and feature pores larger than 300 µm to support cell penetration and bone tissue growth [

1,

2]. In recent years, natural polymers like collagen, gelatin, alginate, and chitosan have gained popularity for scaffold creation in bone tissue engineering. These polymers are favored for their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxic nature, and they offer structural characteristics similar to the native extracellular matrix, enabling enhanced cell interaction, attachment, and growth [

3].

Chitosan (CS) is widely regarded as a key natural polymer for scaffold fabrication in bone tissue engineering [

4]. It consists of linear chains of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine units connected by β (1-4) glycosidic bonds. CS is obtained by deacetylating chitin, a substance found in the shells of crustaceans like shrimp and crabs [

5]. CS closely resembles glycosaminoglycans, key bone and cartilage extracellular matrix components, where they interact with collagen fibers and support cell-cell adhesion [

6,

7]. CS scaffolds have demonstrated the ability to support osteoblastic cell attachment and proliferation, exhibiting strong osteoconductivity that promotes bone growth both in vitro and in vivo studies [

8,

9]. Despite their benefits, CS scaffolds have limited mechanical strength, restricting their use in load-bearing applications. Combining CS with other polymers to create composite scaffolds has become a promising solution to address this limitation. This approach has generated significant attention for its potential in advancing new applications [

10,

11].

Bacterial cellulose (BC) is a white gelatinous substance produced by specific bacteria such as

Acetobacter xylinum [

12]. The chemical structure of BC is similar to CS, with the key difference being that BC contains a hydroxyl group at the C-2 position on the glucose molecule rather than the amino group found in CS [

13]. BC offers several valuable properties, including excellent biocompatibility, a highly porous three-dimensional nanofibrillar structure, superior mechanical strength in dry and wet conditions, and an impressive ability to retain water. These attributes make BC an ideal material for biomedical applications, such as drug delivery, artificial skin, blood vessels, wound care, and tissue engineering scaffolds [

14].

The combination of chitosan (CS) and bacterial cellulose (BC) has gained considerable attention because their structural similarities lead to composite materials that harness the biological benefits of CS and the enhanced mechanical strength of BC [

15]. Various studies have explored the production of CS-BC composites, such as adding CS to the culture medium during BC biosynthesis or immersing BC in CS solutions. These approaches have demonstrated that CS can integrate with BC microfibrils, forming a denser network structure within the composite material [

16,

17]. Additionally, CS molecules can occupy the voids in the BC network, fostering strong interactions between the two components [

18]. Although CS-BC composite materials show improved mechanical properties, enhanced cell attachment, and better cell growth compared to individual BC or CS, the pore size in the composite materials tends to decrease relative to that of natural BC. This is attributed to the incorporation of CS into the BC network [

19,

20]. The pore size of natural BC pellicles is typically under 100 nm, which can hinder cell infiltration and migration [

21].

Various methods for creating polymer scaffolds have been developed, such as solvent casting/particulate leaching (SCPL), freeze-drying, gas foaming, electrospinning, and phase separation [

22]. SCPL is the most commonly used method due to its straightforward process. The process involves dissolving a polymer in a solvent, combining it with a porogen such as sodium chloride (NaCl) crystals, molding the mixture, and then leaching the porogen and solvent to create a porous scaffold [

23]. One of the key benefits of SCPL is that it allows precise control over the porosity and pore size of the scaffold by adjusting the quantity and particle size of the NaCl crystals incorporated into the mixture [

24]. Our previous work successfully fabricated a CS-BC composite scaffold with a three-dimensional porous structure using the SCPL method. We dissolved CS and BC in a sodium hydroxide (NaOH)/urea solution, and added NaCl crystals (450-500 μm) in the mixture to achieve the desired porosity and pore size. The resulting CS-BC composite scaffold had a porosity of about 92% and pore sizes averaging 300-500 μm, along with strong mechanical properties and high water absorption [

25]. However, its biocompatibility and biodegradability still need to be thoroughly investigated to evaluate how the incorporation of CS with BC affects the scaffold's performance, which is essential for determining its suitability for bone tissue engineering. So, this study aims to evaluate the in vitro biodegradation and osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells on the CS-BC composite scaffold prepared via the SCPL method by analyzing cell attachment, proliferation, and osteogenic-gene expression using real time-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of CS-BC Composite Scaffold

In our previous report, we successfully fabricated a porous CS-BC composite scaffold with a 1:1 weight ratio using the SCPL method. The process began by dissolving 0.1 g of chitosan (CS) powder (extracted from shrimp shells, ≥75% deacetylated, C3646-25G, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in 10 mL of a NaOH/urea/water solution pre-cooled to -12 °C (weight ratio 7:12:81, KA482 and KA817, KEMAUS, Australia) to prepare a 1 wt% CS solution. This solution underwent six freeze-thaw cycles to improve its consistency. 0.1 g of bacterial cellulose (BC) powder was added and gently mixed at -12 °C to achieve a uniform solution. Following this, 8 g of sodium chloride (NaCl) crystals (KA465, KEMAUS, Australia), with particle sizes between 450 and 500 μm, were added and evenly distributed throughout the CS-BC mixture. The prepared solution was transferred into a glass tube and left to solidify. It was then immersed in distilled water multiple times until the pH reached 7. The sample underwent overnight freezing at -20 °C, followed by a 24-hour freeze-drying process at -50 °C using a freeze-dryer (Millrock Technology Inc., New York, USA).

2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 250, Netherlands) was used to observe the porous structural scaffolds. Cross-sectional scaffolds were mounted on the adhesive aluminum stubs and covered with a thin gold layer using a modular coater system (Quorum Model Q150R, United Kingdom). The images were captured using an acceleration voltage of 15 to 20 kV to evaluate detailed surface and structural characteristics.

2.3. In Vitro Biodegradable Study

The scaffold’s biodegradability was assessed through an in vitro biodegradation study. The samples were immersed in 5 mL of PBS-lysozyme solution (pH 7.4) containing 10,000 U/mL lysozyme from Sigma-Aldrich (L1667, USA), kept under 37 °C of an incubator and the fresh solution was replaced every 3 days [

26]. The scaffold’s initial dry weight was denoted as Wi. After being incubated for 7, 14, and 21 days, the scaffolds were removed from the solution, rinsed gently with distilled water, and dried in an oven at 35 °C. The dried scaffolds were again weighted and denoted as Wt. The scaffolds submerged in PBS solution without lysozyme were also performed as the control group. A percentage of weight loss (W

L%) due to the scaffold’s biodegradability was determined using the following equation:

2.4. In Vitro Biocompatible Study

2.4.1. Cell Culturing and Seeding Procedure

The preosteoblastic mouse cell line, MC3T3-E1, was cultured in a growth medium supplemented with alpha-MEM (SH30265.02, Cytiva, HyClone Laboratories, Utah, USA), 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum, 1600044, Gibco, USA) and 1% antibiotic mix (penicillin/streptomycin,15240062, Gibco, USA), and maintained in a 5% CO₂ incubator at 37 °C. Before testing, the circular discs of scaffolds (15x1 mm) were sterilized using 70% ethanol and UV light for 10 and 20 minutes, respectively. Sterilized scaffolds were then placed into the 24-well tissue culture plates, pre-incubated in growth medium at 37 °C overnight, and seeded with 3.5 × 10⁴ cells per well directly onto each scaffold in triplicate. Control wells without scaffolds were also included for comparison. The fresh growth medium was replacled every two days.

2.4.2. Cell Attachment

SEM examined the MC3T3-E1 cells attached to CS-BC scaffolds following incubation for 1, 3, and 7 days, with preparation steps including PBS washing, fixation, dehydration, drying, and gold sputter-coating.

2.4.3. Cell Proliferation

The MTT assay (M6494, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was performed to evaluate cell proliferation on CS-BC scaffolds at a determined time (on days 1, 3, and 7). After washing in PBS solution, each sample well was treated with 500 µL of MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL in phenol red-free DMEM) and incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 4 hours. Afterward, the MTT solution was replaced with dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to dissolve the formazan crystals, and the optical density (OD) values were measured in triplicate at 570 nm.

2.5. Cell Differentiation

Following 24 hours of seeding, the growth medium was replaced with an osteogenic medium to promote osteoblastic differentiation. The osteogenic medium comprised of the growth medium, 50 µg/mL L-ascorbic acid (A92902, Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 10 nM dexamethasone (D4902, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 10 nM β-glycerophosphate (G9422, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The cultures were set at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ incubator, maintained for 7, 14 and 21 days, and the fresh medium was renewed every two days.

2.5.1. Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Enzyme Activity Assay

ALP activity, which indicates osteoblastic differentiation, was measured using the BCIP/NBT substrate system (203790, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) following the protocol of Wang et al. [

27], with OD readings taken at 405 nm.

2.5.2. Gene Expression Analysis by RT-qPCR

Cellular RNA was isolated from MC3T3-E1 cells in triplicate composite scaffolds using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA synthesis was performed using a reverse transcription kit (iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix, Bio-Rad, USA), following the supplier’s protocol. A thermal cycler (T100, Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., USA) performed the reverse transcription condition at 25 °C for 5 minutes, 46 °C for 20 minutes and 95 °C for 1 minute, respectively. Osteoblastic differentiation was evaluated by RT-qPCR using the FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Mix kit (Roche Diagnostics, Germany). The reactions were operated with a LightCycler 480 II system (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) and the following settings: 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 seconds, 58 °C for 30 seconds, and 72 °C for 30 seconds. Negative controls without cDNA were included to ensure specificity. Specific primers for osteocalcin (OCN), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), collagen type I (COL-1), and bone sialoprotein (BSP) were used to check osteogenic-related gene, which were normalized against the expression level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, as internal control) with results expressed as fold changes compared to controls [

28], all primers are listed in

Table 1.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was conducted in triplicate, and the data are expressed as mean values with corresponding standard deviations. The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed data normality, while Levene's test was applied to evaluate variance homogeneity. For statistical comparisons, an independent t-test was employed for two-group analyses, while one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc tests was used for multi-group comparisons. IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to conduct the statistical analyses and all graphical data visualizations were created with GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. SEM Analysis of CS-BC Composite Scaffold Morphology

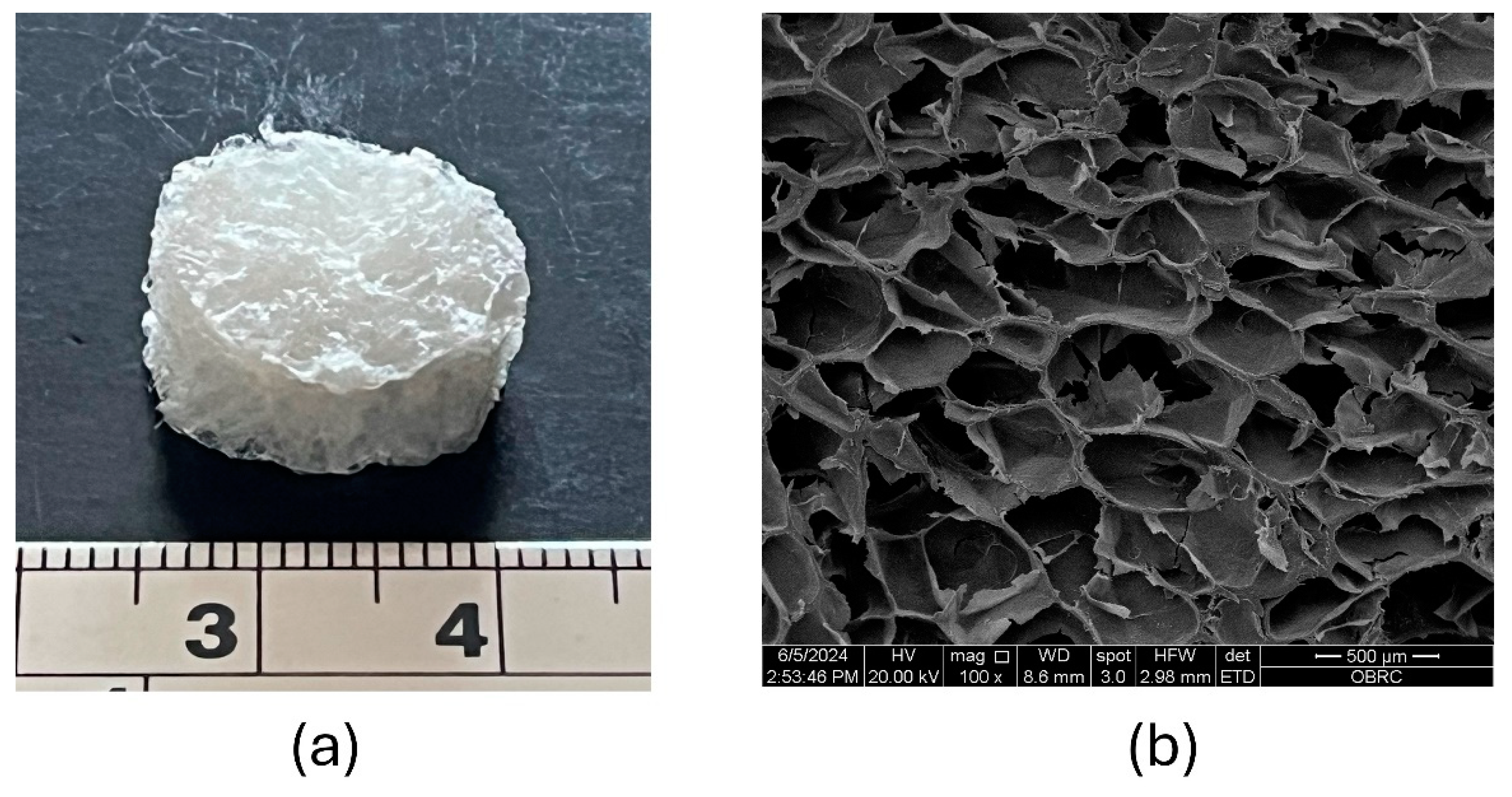

The CS-BC composite scaffold fabricated using the SCPL method is depicted in

Figure 1a, showcasing a three-dimensional porous sponge structure after the freeze-drying process. The SEM image in

Figure 1b illustrates the cross-section of the freeze-dried CS-BC composite sponge, revealing a porous network with uniformly distributed pores and rough pore walls. The pore sizes ranging from approximately 300 to 500 µm were revealed. These structural characteristics suggest that the CS-BC composite scaffold possesses favorable morphology and pore size.

3.2. The Biodegradation of CS-BC Scaffold

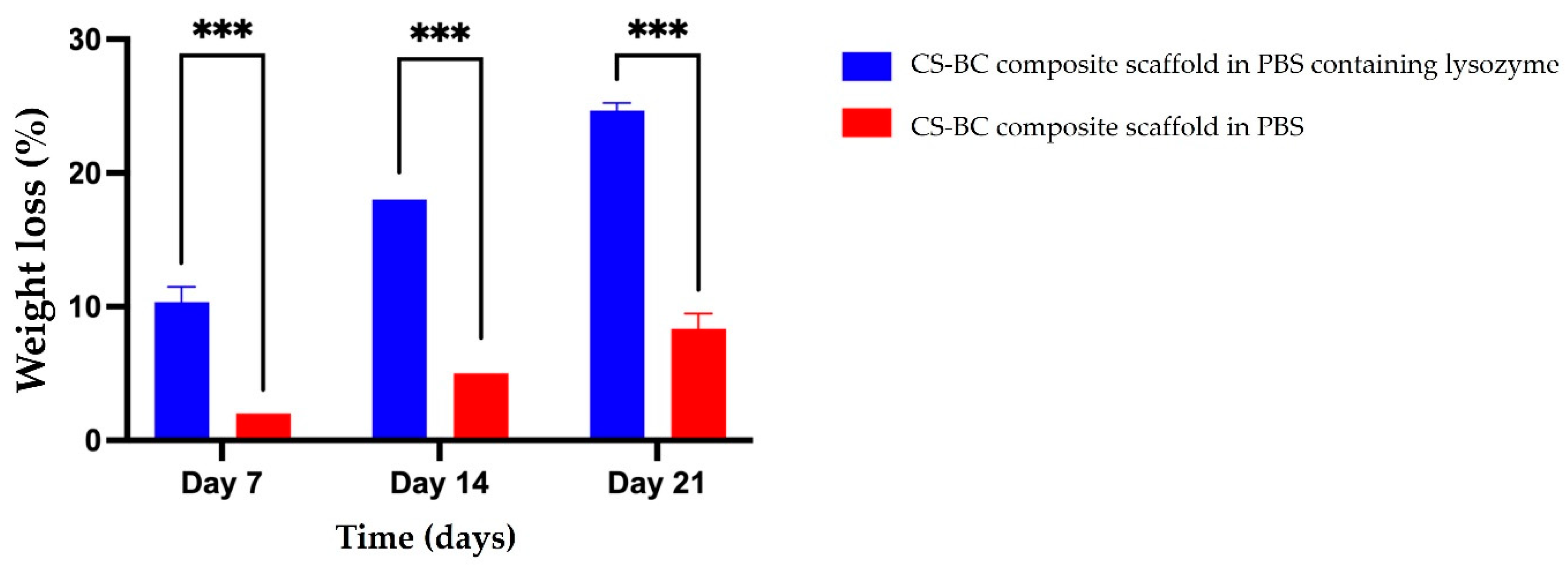

The biodegradation behavior of the developed CS-BC composite scaffolds was evaluated through an in vitro study. The scaffolds were immersed in PBS solution with and without lysozyme, and the weight loss percentage was assessed over various time points (7, 14, and 21 days), as shown in

Figure 2. The results revealed a gradual increase in weight loss across all groups throughout the degradation period. Precisely, the weight loss of the CS-BC composite scaffolds was measured at 10% (±1.15), 18% (±0.00), and 24% (±0.58) on days 7, 14, and 21, respectively. The control group showed weight loss of 2% (±0.00), 5% (±0.00), and 8% (±1.15) at the respective time points, demonstrating that the CS-BC composite scaffolds experienced significantly more significant weight loss. The results confirm the biodegradability of CS-BC scaffolds in the presence of lysozyme, with their degradation rate dependent on the incubation duration.

3.3. MC3T3-E1 Cell Attachment and Proliferation on the CS-BC Composite Scaffold

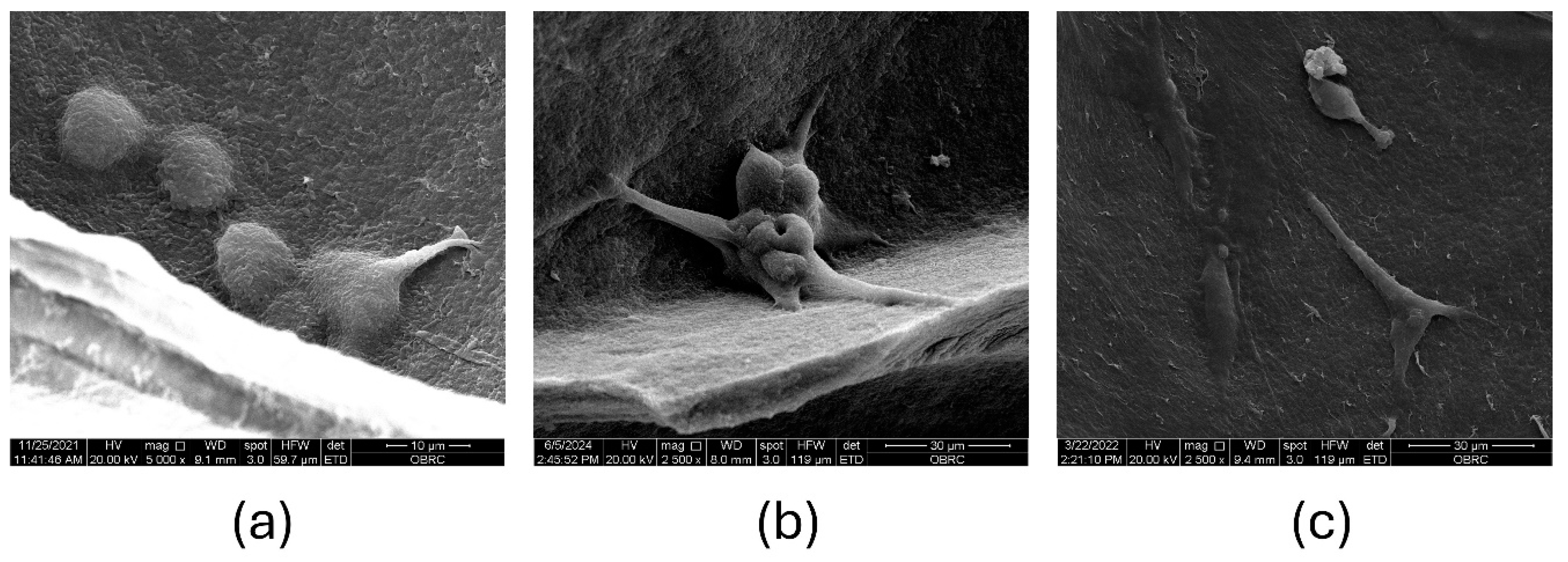

The evaluation of MC3T3-E1 cell attachment and proliferation on the CS-BC scaffold are depicted in

Figures 3a-c. On day 1 post-seeding, SEM images revealed individual cells with a spherical morphology beginning to adhere to the pore walls of the composite scaffold (

Figure 3a). The cells appeared evenly distributed across the surface, indicating efficient seeding. The initial spherical shape suggests that the cells were in the early stages of attachment as they began establishing interactions with the scaffold material. By day 3, the cells exhibited an irregular, rounded morphology with visible microvilli-like projections extending to anchor themselves to the scaffold surface (

Figure 3b). These projections indicate active cell-scaffold interaction, which is crucial for promoting cellular adhesion and subsequent proliferation. The cells appeared to bridge across the pores, demonstrating the scaffold's ability to support cellular spreading and integration. By day 7, the cells displayed a flattened shape and remained securely attached to the pore walls of the scaffold (

Figure 3c). This morphological change suggests that the cells had adapted to the scaffold's surface and achieved stable adhesion. Additionally, the cells showed signs of forming a continuous layer, potentially indicating the onset of extracellular matrix production.

Cell proliferation was assessed quantitatively using the MTT assay, with results presented in

Figure 4. The optical density (OD) values of the cells cultured on the composite scaffold increased progressively throughout the experiment, indicating enhanced metabolic activity and proliferation over time. On day 1, the OD value for MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on the CS-BC composite scaffold was significantly lower than the control group, suggesting that the initial adhesion phase required an adjustment period as the cells adapted to the scaffold's surface. However, by day 3, the OD value for the composite scaffold group showed a marked increase, surpassing the control, highlighting the scaffold's supportive environment for cellular proliferation. By day 7, the OD values of both groups were comparable, with no statistically significant difference (ns), indicating consistent cell viability across both conditions. The results of the MTT assay (

Figure 4) underscore the CS-BC composite scaffold's ability to sustain cellular attachment and promote proliferation over time. The observed increase in OD values from day 1 to day 7 reflects the scaffold's biocompatibility and capacity to support the metabolic activity of MC3T3-E1 cells. These findings further confirm that the scaffold provides a favorable microenvironment for cellular growth. This makes it a potential candidate for bone tissue engineering applications.

3.4. MC3C3-E1 Cell Differentiation on the CS-BC Composite Scaffold

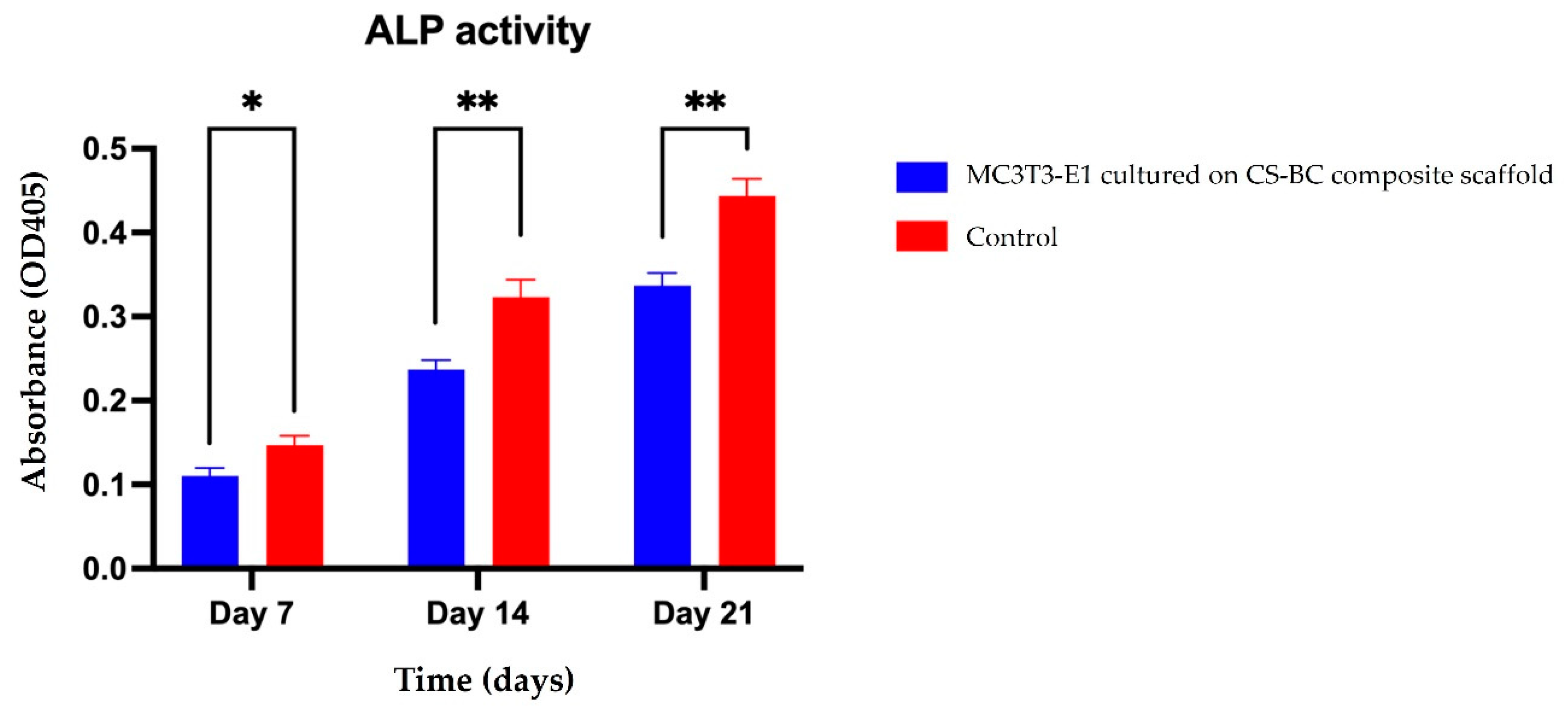

Early markers of osteoblastic differentiation, such as ALP enzyme activity, reflect the progression of the osteogenic process.

Figure 5 presents the ALP activity of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on the CS-BC composite scaffold under osteogenic induction conditions over 21 days. The optical density (OD) values showed a time-dependent increase in ALP activity, highlighting the scaffold's supportive role in cell differentiation. On day 7, the ALP activity was relatively low, suggesting that the cells were in the early stages of differentiation. By day 14, a notable increase in ALP activity was observed, indicating that the cells were advancing toward osteoblastic maturation. On day 21, ALP activity peaked, approximately doubling compared to the levels recorded on day 7 and showing a further increase compared to day 14. These findings emphasize the CS-BC composite scaffold's potential to effectively promote and sustain osteoblastic differentiation over time.

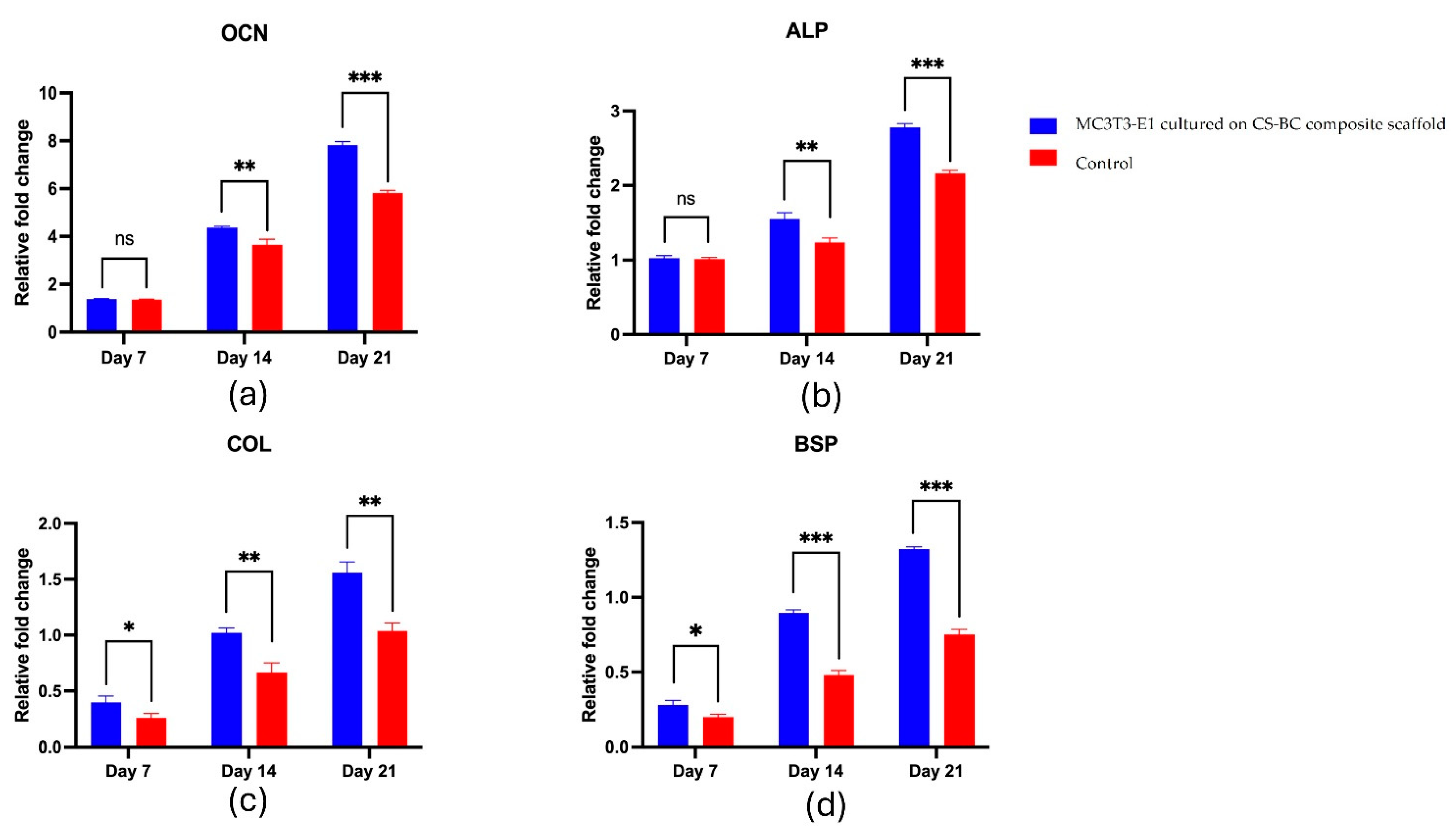

The gene expression analysis revealed a gradual increase in key osteogenic markers over 21 days. The mRNA levels of OCN, ALP, COL-1, and BSP progressively elevated in the scaffold group and were consistently higher than in the control group, as shown in

Figure 6a-d. OCN expression remained similar to the control on Day 7, then significantly increased by Day 14, peaking at Day 21 (

Figure 6a). ALP showed no significant difference on Day 7 but rose significantly by Day 14 and continued to increase through Day 21 (

Figure 6b). COL-1 exhibited a moderate yet significant increase on Day 7, further intensifying on Day 14 and reaching a marked elevation by Day 21 (

Figure 6c). Likewise, BSP expression was comparable to the control on Day 7 but significantly increased on Day 14 and peaked on Day 21 (

Figure 6d). Overall, these results suggest that the CS-BC scaffold supports osteogenic differentiation effectively.

4. Discussion

A suitable scaffold for tissue engineering of bone should offer a well-defined three-dimensional porous structure and sufficient mechanical stability. In addition, it must exhibit biodegradability and biocompatibility, ensuring non-toxicity while supporting cell adhesion, cell division, cell proliferation, and cell differentiation toward the formation of new bone tissue [

29]. This study fabricated a CS-BC composite scaffold using the SCPL method, with NaOH/urea solution as the solvent and NaCl particles as the pore-forming agent. The scaffold displayed a porous structure with pore sizes between 300 and 500 µm. Its morphology revealed high porosity, a connected pore network, and consistent pore distribution with surface roughness. These features are critical for facilitating nutrient exchange and promoting effective cell attachment, which is essential for tissue regeneration. Previous research has indicated that increased pore roughness enhances cell spreading, while pore sizes exceeding 300 µm are particularly conducive to cell infiltration. Such pore dimensions are widely regarded as optimal for supporting bone tissue formation. [

30,

31].

Biodegradation is a critical property of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering, requiring them to gradually degrade to create space for new bone growth and matrix deposition following cell proliferation [

32]. This study assessed the in vitro biodegradation of CS-BC composite scaffolds using a PBS solution containing lysozyme, an enzyme naturally present in various human and animal tissues and fluids [

33]. The results showed a consistent reduction in the scaffolds’ weight over time, indicating their biodegradability in the presence of lysozyme. This degradation behavior is likely due to the β (1→4) glycosidic bonds between glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine in chitosan, which lysozyme can cleave [

34]. Additionally, bacterial cellulose may contribute to the degradation process due to its structural instability, reduced crystallinity, and the morphological characteristics of the scaffold [

35]. The findings suggest that the CS-BC composite scaffold has a prolonged degradation rate, making it a strong contender for bone tissue engineering applications.

The biocompatibility of scaffolds is essential in bone tissue engineering, as it directly influences cellular adherence, cell division, proliferation, and differentiation [

36]. In this study, the CS-BC composite scaffold demonstrated excellent biocompatibility with MC3T3-E1 cells, supporting their attachment and proliferation without exhibiting cytotoxic effects. The scaffold’s natural composition, derived from CS and BC, and its extracellular matrix-like structure significantly enhanced osteoblastic attachment and proliferation [

37,

38]. These properties underline the suitability of CS-BC scaffolds for bone tissue applications. Furthermore, the scaffold's ability to promote early osteoblastic differentiation was demonstrated by increased ALP activity and the showing of osteogenesis-related genes [

39]. These findings suggest that CS-BC composite scaffolds hold promise as a viable substrate for promoting bone regeneration in tissue engineering applications.

The initiation of osteoblastic differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells is marked by increased ALP activity, a critical process for promoting bone mineralization [

40]. In this study, the CS-BC composite scaffold demonstrated the ability to enhance ALP activity over time, confirming its role in supporting the differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells. The scaffold also facilitated the upregulation of key osteogenic-related genes, including OCN, ALP, COL-1, and BSP, which are essential for various stages of osteoblastic differentiation [

41,

42]. OCN, pivotal in bone matrix formation, showed elevated expression, indicating the transition of cells to the mineralization phase [

43]. ALP plays a key role in extracellular matrix mineralization, with its expression rising during differentiation, serving as a marker for osteoblast differentiation [

44]. COL-1, the primary component of the bone matrix, is produced during the differentiation of osteoblasts [

45]. Moreover, BSP is a marker for late differentiation of osteoblasts and a gene related to the mineralization phase of bone formation and support cell attachment [

46]. The relative expression level of OCN, ALP, COL-1 and BSP had been observed in the in vitro studies in various composite scaffolds such as CS/hydroxyapatite/collagen, hydroxyapatite/CS/gelatin, BC/collagen, BC/gelatin/hydroxyapatite and polyglycolide/ polycaprolactone. These gene expressions were found to be low on the initial time, but they were significantly upregulated over time and demonstrated notable differences when compared to the control group [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Our findings revealed that the expression levels of osteogenic-related genes, OCN, ALP, COL-1, and BSP, in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on the CS-BC composite scaffold consistently increased over time and were considerably more remarkable than the control group. These results highlight the ability of the CS-BC composite scaffold to enhance the osteoblastic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed a CS-BC composite scaffold, demonstrating its practical potential for bone tissue regeneration applications. The scaffold was produced using the SCPL method, with NaOH/urea solution as the solvent and NaCl particle as a porogen to create a three-dimensional porous structure characterized by high porosity and pore sizes exceeding 300 µm. The CS-BC composite scaffold demonstrated excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability, providing a supportive environment for MC3T3-E1 cell adherence, cell division, proliferation, and osteoblastic differentiation. Further investigations, particularly in vivo studies, are essential to comprehensively evaluate the scaffold's osteogenic capabilities and potential for clinical applications in bone regeneration.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org., Table 1: Osteogenic-related genes and primer sequences for RT-qPCR analysis in MC3T3-E1.; Figure S1: Photograph of the freeze-dried CS-BC composite sponge (a) and SEM image of the surface morphology and porosity of the cross-sectional scaffold (b) at 100X magnification.; Figure S2. Percentage of weight loss of CS-BC composite scaffolds following immersion in PBS with and without lysozyme at different time intervals. Statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.; Figure S3. SEM images showing the attachment of MC3T3-E1 cells on CS-BC composite scaffolds: Day 1 at 5,000X magnification (a), Day 3 at 2,500X magnification (b), and Day 7 at 2,500X magnification (c).; Figure S4. Proliferation of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds compared to the control group (scaffold-free) at days 1, 3, and 7 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns: not significant).; Figure S5. ALP activity of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds and scaffold-free control groups at days 7, 14, and 21 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).; Figure 6. RT-qPCR analysis for OCN (a), ALP (b), COL-1 (c), and BSP (d) expression in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds and scaffold-free control groups at days 7, 14, and 21 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., S.P. and S.S.; methodology, S.Y., S.P. and S.S.; software, S.C.; validation, S.Y., S.P. and S.C.; formal analysis, S.Y.; investigation, S.Y.; resources, S.Y. and S.S.; data curation, S.Y., S.P., S.C. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; visualization, S.Y. and S.C.; supervision, S.P.; project administration, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the excellent technical support of Dr. Narin Intarak and Dr. Tipthanan Chotipinit, Center of Excellence in Genomics and Precision Dentistry, Clinical Research Center, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. We are grateful to Prof. Thantrira Porntaveetus, Mr. Noppadol Sa-Ard-Iam and the Biomaterial Testing Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, for their facilities and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wubneh, A.; Tsekoura, E.K.; Ayranci, C.; Uludağ, H. Current state of fabrication technologies and materials for bone tissue engineering. Acta. Biomater 2018, 80, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.T.; Munguia-Lopez, J.G.; Cho, Y.W.; Ma, X.; Song, V.; Zhu, Z.; Tran, S.D. Polymeric scaffolds for dental, oral, and craniofacial regenerative medicine. Molecules 2021, 26, 7043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chocholata, P.; Kulda, V.; Babuska, V. Fabrication of scaffolds for bone-tissue regeneration. Materials 2019, 12, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hasan, A.; Negi, Y.S. Effect of Carbon-based fillers on xylan/chitosan/nano-HAp composite matrix for bone tissue engineering application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 197, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavya, K.C.; Jayakumar, R.; Nair, S.; Chennazhi, K.P. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan/gelatin/nSiO2 composite scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 59, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Baek, S.D.; Venkatesan, J.; Bhatnagar, I.; Chang, H.K.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, S.K. In vivo study of chitosan-natural nano hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 67, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januariyasa, I.K.; Ana, I.D.; Yusuf, Y. Nanofibrous poly (vinyl alcohol)/chitosan contained carbonated hydroxyapatite nanoparticles scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 107, 110347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Ali, M.; Zeeshan, R.; Mutahir, Z.; Iqbal, F.; Nawaz, M.A.H.; Shahzadi, L.; Chaudhry, A.A.; Yar, M.; Luan, S.; Khan, A.F.; Rehman, I.U. Chitosan/hydroxyapatite (HA)/hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose (HPMC) spongy scaffolds-synthesis and evaluation as potential alveolar bone substitutes. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces. 2017, 160, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Porous chitosan/nano-hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds incorporating simvastatin-loaded PLGA microspheres for bone repair. Cells Tissues Organs 2018, 205, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, J.; Pallela, R.; Bhatnagar, I.; Kim, S.K. Chitosan-amylopectin/hydroxyapatite and chitosan-chondroitin sulphate/hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanimozhi, K.; Khaleel-Basha, S.; Sugantha-Kumari, V. Processing and characterization of chitosan/PVA and methylcellulose porous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 61, 484–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stumpf, T.R.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Cao, X. In situ and ex situ modifications of bacterial cellulose for applications in tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018, 82, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, F.; Hu, X.H.; Chu, L.Q.; Jia, S.R.; Xie, Y.Y.; Zhong, C. Development of bacterial cellulose/chitosan based semi-interpenetrating hydrogels with improved mechanical and antibacterial properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Barud, H.G.; da Silva, R.R.; da Silva Barud, H.; Tercjak, A.; Gutierrez, J.; Lustri, W.R.; de Oliveira, O.B.J.; Ribeiro, S.J.L. A multipurpose natural and renewable polymer in medical applications: bacterial cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 153, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.C.; Lien, C.C.; Yeh, H.J.; Yu, C.M.; Hsu, S.H. Bacterial cellulose and bacterial cellulose-chitosan membranes for wound dressing applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina, L.; Guaresti, O.; Requires, J.; Gabilondo, N.; Eceiza, A.; Corcuera, M.A.; Retegi, A. Design of reusable novel membranes based on bacterial cellulose and chitosan for the filtration of copper in wastewaters. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 193, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikibe, J.E.; Lata, R.; Rohindra, D. Bacterial cellulose/chitosan hydrogels synthesized in situ for biomedical application. J. Appl. Biosci. 2021, 162, 16675–16693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecka-Zelga, J.; Zelga, P.; Szulc, J.; Wietecha, J.; Ciechańska, D. An in vivo biocompatibility study of surgical meshes made from bacterial cellulose modified with chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, N.; Du, R.; Zhao, F.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Z. Characterization of antibacterial bacterial cellulose composite membranes modified with chitosan or chitooligosaccharide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, V.A.; Gofman, I.V.; Dubashynskaya, N.V.; Golovkin, A.S.; Mishanin, A.I.; Ivan'kova, E.M.; Romanov, D.P.; Khripunov, A.K.; Vlasova, E.N.; Migunova, A.V.; Baranchikov, A.E.; Ivanov, V.K.; Yakimansky, A.V.; Skorik, Y.A. Chitosan composites with bacterial cellulose nanofibers doped with nanosized cerium oxide: characterization and cytocompatibility evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Mishra, R.; Roy, P.; Singh, R.P. 3-D macro/microporous-nanofibrous bacterial cellulose scaffolds seeded with BMP-2 preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells exhibit remarkable potential for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, G.; Clarke, J.; Picard, F.; Riches, P.; Jia, L.; Han, F.; Li, B.; Shu, W. 3D bioactive composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2017, 3, 278–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Lee, K.; Wang, X.; Yoshitomi, T.; Kawazoe, N.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G. Interconnected collagen porous scaffolds prepared with sacrificial PLGA sponge templates for cartilage tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 8491–8500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.; Bertacchini, J.; D'Avella, D.; Anselmi, L.; Maraldi, T.; Marmiroli, S.; Messori, M. Development of solvent-casting particulate leaching (SCPL) polymer scaffolds as improved three-dimensional supports to mimic the bone marrow niche. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 96, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodsanga, S.; Poeaim, S. Effect of NaOH/urea solution as a solvent and salt crystals as a porogen on the fabrication of porous composite scaffold of bacterial cellulose-chitosan for tissue engineering. Int. J. Agric. Technol. 2024, 20, 877–892, https://doi.org/ijat‐aatsea.com/past_v20_n2.html. [Google Scholar]

- Shakir, M.; Zia, I.; Rehman, A.; Ullah, R. Fabrication and characterization of nanoengineered biocompatible n-HA/chitosan-tamarind seed polysaccharide: bio-inspired nanocomposites for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, S.; Chai, S.; Wang, P.; Qin, J.; Pei, W.; Bian, H.; Jiang, Q.; Huang, C. Preparing printable bacterial cellulose based gelatin gel to promote in vivo bone regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, X. An improvement of the 2ˆ(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat. Bioinforma. Biomath. 2013, 3, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Motiee, E.S.; Karbasi, S.; Bidram, E.; Sheikholeslam, M. Investigation of physical, mechanical and biological properties of polyhydroxybutyrate-chitosan/graphene oxide nanocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 247, 125593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thadavirul, N.; Pavasant, P.; Supaphol, P. Development of polycaprolactone porous scaffolds by combining solvent casting, particulate leaching, and polymer leaching techniques for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 3379–3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Wu, W.; Qing, Y.; Tang, X.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, Y. Adhesion and proliferation of osteoblast-like cells on porous polyetherimide scaffolds. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1491028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A.; Mondal, T.; Bhattacharya, J. An in vitro evaluation of zinc silicate fortified chitosan scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020, 164, 4252–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Dinda, A.K.; Potdar, P.D.; Chou, C.F.; Mishra, N.C. Fabrication and characterization of novel nano-biocomposite scaffold of chitosan-gelatin-alginate-hydroxyapatite for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 64, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atak, B.H.; Buyuk, B.; Huysal, M.; Isik, S.; Senel, M.; Metzger, W.; Cetin, G. Preparation and characterization of amine functional nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan bionanocomposite for bone tissue engineering applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 164, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zha, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Ren, R.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhao, L. A janus, robust, biodegradable bacterial cellulose/Ti3C2Tx MXene bilayer membranes for guided bone regeneration. Biomaterials Advances 2024, 161, 213892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Hu, X.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Peng, L.; Chen, D.; Xiong, C.; Zhang, L. Chitosan-coated hydroxyapatite and drug-loaded polytrimethylene carbonate/polylactic acid scaffold for enhancing bone regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 253, 117198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L.; Jung, G.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Han, J.S.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, D.G; Zhang, M.; Kim, D.J. Preparation and characterization of nano-sized hydroxyapatite/alginate/chitosan composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 54, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. , Yang, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, D. Biomimetic design of platelet-rich plasma controlled release bacterial cellulose/hydroxyapatite composite hydrogel for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, N.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, P. Modulation of osteogenesis in MC3T3-E1 cells by different frequency electrical stimulation. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0154924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Qin, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhou, L.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Ye, L.; Yue, S.; Zheng, Q.; Li, D. Astragalin promotes osteoblastic differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells and bone formation in vivo. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.G.; Cho, I.H. Characteristics and osteogenic effect of zirconia porous scaffold coated with β-TCP/HA. J. Adv. Prosthodont 2014, 6, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Gao, J.; Xing, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, G. Comparative evaluation of the physicochemical properties of nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen and natural bone ceramic/collagen scaffolds and their osteogenesis-promoting effect on MC3T3-E1 cells. Regen. Biomater. 2019, 6, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Pu, X.; Liao, X.; Huang, Z.; Yin, G. A novel akermanite/poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) porous composite scaffold fabricated via a solvent casting-particulate leaching method improved by solvent self-proliferating process. Regen. Biomater. 2017, 4, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Lin, S.; Rizkalla, A.S.; Mequanint, K. Porous and biodegradable polycaprolactone-borophosphosilicate hybrid scaffolds for osteoblast infiltration and stem cell differentiation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 92, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, M.J.; Lim, D.S.; Kim, S.O.; Park, C.; Choi, Y.H.; Jeong, S.J. Effect of rosmarinic acid on differentiation and mineralization of MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells on titanium surface. Anim. Cells Syst. 2021, 25, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriero Mdel, M.; Ramis, J.M.; Perelló, J.; Monjo, M. Differential response of MC3T3-E1 and human mesenchymal stem cells to inositol hexakisphosphate. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 30, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Chi, Z.; Yang, R.; Xu, D.; Cui, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Liu, C. Chitin-hydroxyapatite-collagen composite scaffolds for bone regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 184, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, P.; Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Gao, Y.; Guo, Y. Nacre-mimetic hydroxyapatite/chitosan/gelatin layered scaffolds modifying substance P for subchondral bone regeneration. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, XC.; Li, XY.; Zhang, L.L.; Jiang, F. A 3D porous microsphere with multistage structure and component based on bacterial cellulose and collagen for bone tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dai, K. Modification and evaluation of micro-nano structured porous bacterial cellulose scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 75, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Gao, G.; Yin, X.; Pu, X.; Shi, B.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yin, G. MBG/ PGA-PCL composite scaffolds provide highly tunable degradation and osteogenic features. Bioactive Materials 2022, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Photograph of the freeze-dried CS-BC composite sponge (a) and SEM image of the surface morphology and porosity of the cross-sectional scaffold (b) at 100X magnification.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the freeze-dried CS-BC composite sponge (a) and SEM image of the surface morphology and porosity of the cross-sectional scaffold (b) at 100X magnification.

Figure 2.

Percentage of weight loss of CS-BC composite scaffolds following immersion in PBS with and without lysozyme at different time intervals. Statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Percentage of weight loss of CS-BC composite scaffolds following immersion in PBS with and without lysozyme at different time intervals. Statistical significance is indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

The attachment of MC3T3-E1 cells on the CS-BC composite scaffolds was evaluated through SEM images: Day 1 at 5,000X magnification (a), Day 3 at 2,500X magnification (b), and Day 7 at 2,500X magnification (c).

Figure 3.

The attachment of MC3T3-E1 cells on the CS-BC composite scaffolds was evaluated through SEM images: Day 1 at 5,000X magnification (a), Day 3 at 2,500X magnification (b), and Day 7 at 2,500X magnification (c).

Figure 4.

MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation on CS-BC composite scaffolds was compared to the control group (scaffold-free) on days 1, 3, and 7 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns: not significant).

Figure 4.

MC3T3-E1 cell proliferation on CS-BC composite scaffolds was compared to the control group (scaffold-free) on days 1, 3, and 7 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns: not significant).

Figure 5.

ALP activity of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds and scaffold-free control groups at days 7, 14, and 21 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

ALP activity of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds and scaffold-free control groups at days 7, 14, and 21 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR analysis for OCN (a), ALP (b), COL-1 (c), and BSP (d) expression in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds and scaffold-free control groups at days 7, 14, and 21 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR analysis for OCN (a), ALP (b), COL-1 (c), and BSP (d) expression in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on CS-BC composite scaffolds and scaffold-free control groups at days 7, 14, and 21 (Statistical significance indicated as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Osteogenic-related genes and primer sequences for RT-qPCR analysis in MC3T3-E1 cells.

Table 1.

Osteogenic-related genes and primer sequences for RT-qPCR analysis in MC3T3-E1 cells.

| Gene names |

Forward/Reverse primer sequences |

| OCN |

5’-TGACCTCACAGATCCCAAGCC-3’/5’-ATACCGTAGATGCGTTTGTAGGC-3’ |

| ALP |

5’-CCTTGCCTGTATCTGGAATCCT-3’/5’-GTGCAGTCTGTGTCTTGCCTG-3’ |

| COL-1 |

5’-GGGTCTAGACATGTTCAGCTTTGTG-3’/5’-ACCCTTAGGCCATTGTGTATGC-3’ |

| BSP |

5’-CCTCCTCTGAAACGGTTTCCA-3’/5’-TCTGCATCTCCAGCCTCCTTG-3’ |

| GAPDH |

5’-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3’/5’-GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA-3’ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).