1. Introduction

Lumpy Skin Disease Virus (LSDV) is a transboundary pathogen affecting cattle and causing significant economic losses, particularly in Africa and Asia. The disease leads to decreased milk production, hide damage, reproductive failures, and high treatment and vaccination costs [

1,

2]. In regions where livestock forms a central component of rural livelihoods and food security, such as sub-Saharan Africa, these impacts are especially devastating [

3]. The global economic burden of LSDV has intensified with its expansion beyond Africa, with outbreaks in Asia alone estimated to have caused losses of approximately USD 1.45 billion [

4]. In Ethiopia, median losses per dead animal were valued at USD 375, with herd-level losses reaching USD 1176 [

5], while the 2022 outbreak in Pakistan affected over 5 million farmers [

1].

Initially endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, LSDV has now been reported across the Middle East, Asia, and Europe, with a rapid geographic expansion observed since 2012, when more than 98% of outbreaks were recorded [

2]. Recent outbreaks in countries such as Russia [

6], China [

7], Turkey [

8], and Nigeria [

9] highlight its widespread distribution. Environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, vector abundance, and land use influence its transmission patterns [

10]. Additionally, informal livestock trade and genetic recombination have contributed to its continued spread [

11].

LSDV is primarily vector-transmitted, with mosquitoes [

12,

13], stable flies [

14,

15], and ticks [

16,

17] identified as key mechanical vectors. While direct transmission between cattle is considered rare, seasonal outbreaks often coincide with peak vector activity [

2]. There is also emerging evidence for venereal, airborne, and alimentary transmission [

18]. Clinically, LSD presents with fever, nodular skin lesions, emaciation, and reproductive failure, leading to substantial morbidity [

19].

Vaccination remains the most effective control strategy, but vaccine efficacy varies by region and strain. In Ethiopia, the Kenyan sheep pox vaccine (KS1 O-180) showed limited effectiveness, with reproduction ratios nearly identical between vaccinated and unvaccinated cattle [

5]. Other studies have also reported vaccine failures in dairy herds [

20]. In contrast, the Neethling vaccine strain (This is a specific strain of LSDV that has been selected and attenuated for use in vaccines), demonstrated significantly better protection in Israel and parts of Europe, with an average efficacy of 79.8% during the 2016–2017 Balkan epidemic [

21,

22]. However, the emergence of new LSDV variants due to genetic mutations and recombination, especially between vaccine and field strains, has raised concerns about current vaccine efficacy [

23,

24,

25].

LSDV has a large double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 151 kilobase pairs, encoding about 156 genes involved in replication, immune evasion, and host range [

26]. Although genetically conserved, LSDV displays sufficient diversity through mutations and recombination to result in distinct viral lineages with different epidemiological profiles [

27]. Recombinant strains have demonstrated altered transmission routes and enhanced oronasal spread, complicating control efforts. Studies in Uganda and Nigeria have shown genetic similarities between African and Eurasian strains [

28], and genomic analysis of LSDV isolates from India and Bangladesh revealed close similarity to historical Kenyan strains, suggesting a common exotic source [

29], emphasizing the need for continuous genomic monitoring.

Despite the African origin of LSDV and its continued burden in African cattle populations, there is a notable shortage of complete genome sequences from West and Central Africa. To date, only one full genome has been reported from this region, limiting our understanding of local viral diversity and hindering efforts to assess vaccine compatibility and strain evolution. Given the increased frequency and severity of outbreaks, it is essential to fill this knowledge gap through regional genomic surveillance and characterization.

This study aims to address this gap by characterising LSDV strains circulating in Nigeria, Cameroon, and the Benin Republic. Through molecular detection, sequencing, and comparative genomic analysis, we provide insights into the evolutionary dynamics of LSDV in West and Central Africa and their implications for disease control and vaccine development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Sample Collection

Samples were collected from cattle from three countries (Nigeria, Cameroon and Benin). Nigeria shares boundaries with both Cameroon and Benin. The sampled animals were from farms, cattle markets and abattoirs. These locations were areas where contact or local veterinarians reported cases of cattle with pox-like lesions. The sampling activity was done by experienced veterinarians who purposefully sampled animals with skin nodules of varying sizes, severity and stages and typical of LSD. Samples collected include skin scabs, nodule aspirates, and oral and nasal swabs (the oral and nasal swabs were pooled into one sample for each animal). Collected samples were stored in DNA/RNA shields and transferred into mobile freezers (-4 °C). Then, they were transported to the Institute for Genomics and Global Health (IGH), Redeemer’s University, Ede, Nigeria, and stored at -80 °C until laboratory analysis.

Figure 1.

Map of Africa highlighting the study area.

Figure 1.

Map of Africa highlighting the study area.

2.2. Fly Collection and Processing

Flies were also collected from sampled sites. The flies were captured using fine-mesh scoop nets and baited conical traps containing FLY IN BAIT® and decomposing organic matter. Captured flies were immediately transferred into labelled zip lock bags and transported in an ice box to maintain the cold chain. Upon arrival at the laboratory, samples were stored at –20°C. Identification was carried out based on morphological characteristics, including sex differentiation and species classification using key features of the head, thorax, abdomen, and general body structure. Processed flies were grouped into pools, each consisting of 10 flies of the same sex and species (fly type). All pools were stored in 1.5 ml safe-lock Eppendorf® tubes containing 500 µl of RNA/DNA Shield for downstream molecular analysis.

2.3. DNA Extraction and qPCR

The extraction process utilised the QIAamp DNA Mini kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The methodologies varied depending on the sample type, particularly involving the homogenisation of skin scabs. A TaqMan-based qRT-PCR analysis was conducted using specific primers (LSDV-F: TGAATTAGTGTTGTTTCTTC; LSDV-R: GGGAATCCTCAAGATAGTTCG) and a probe (LSDV-P: FAM-TGCCGCAAAATGTCGA-MGB) to target the P32 gene of the LSD virus. RT-PCR amplifications were performed in a 25 µl reaction mix containing 5 µl of extracted sample nucleic acid or template controls, along with 20 µl of the prepared master mix. The PCR master mix comprised 6.25 µl of TaqPath 1-Step RT-qPCR reaction mix, 1 µl of each primer, 0.5 µl of probe, and 11.25 µl of nuclease-free water. The thermocycling conditions for the PCR were set at 50 °c for 2 minutes, followed by 95 °c for 5 minutes, and then 40 amplification cycles (95 °c for 15 seconds, 58 °c for 15 seconds). The reaction was performed on a Lightcycler 96 by Roche Sequencing, and a CT value <40 was considered a positive sample.

2.4. Library Construction, Hybridisation Capture and Sequencing

We performed library construction following the methods used by [

30]. Libraries were constructed using the Twist library preparation kits (Twist Biosciences, USA). The indexed libraries were pooled and then set up for liquid hybridisation capture using the VirCapSeq-VERT probe by employing the Twist Fast Hybridisation Reagents (Twist Biosciences, USA). The enriched and purified pools were quantified and thereafter normalised. Paired-end sequencing was carried out using a P3 (300-cycle) cartridge and flowcell on the Illumina NextSeq 2000 instruments (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis to determine the level of significance on the rate of positivity across sampled countries and the sample types was carried out using IBM SPSS 27. P value <0.05 was considered significant.

2.6. Bioinformatics Analysis

The FastQ files generated from sequencing were first taken through FastQC to check for the quality of the reads. Afterwards, the reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic to remove poor-quality reads and adapters. This was followed by taxonomic classification using Kraken2. The pre-processed reads were aligned to the reference genome (NC003027) using BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner). Finally, a consensus genome was generated using iVar. This involved aligning the BAM files, variant calling, and constructing a high-confidence consensus sequence with a read depth of 10x set as the cut-off.

Phylogenetic analysis was done using a final dataset of 34 sequences, consisting of the 2 newly assembled LSDV sequences from this study (with completeness > 90% as compared to the reference genome- NC003027) and 32 sequences retrieved from the NCBI virus database. These 32 sequences were selected as representatives from the different LSDV clusters as outlined by [

31]. The multiple sequence alignment was performed using the online MAFFT tool (MAFFT alignment and NJ/UPGMA). The maximum likelihood tree was constructed using IQTREE2 and iTOL (Interactive Tree of Life) was used for visualisation and annotation.

Variant analysis was done to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs or single-base substitutions) and Indels using NUCmer version 3.1. NUCmer (part of MUMmer) was used for pairwise alignment, comparing the 2 newly assembled Cameroonian genomes and 4 representatives of the established sub-lineages of the 1.2 LSDV cluster [

31] to the LSDV reference genome (NC003027). To refine the alignment data from NUCmer, Delta-filter (a built-in post-processing tool in MUMmer) was used to keep high-quality matches and to eliminate weak alignments. Additionally, AWK (a text-processing tool) was used to remove ambiguous SNPs, ensuring high-quality variant calls.

A custom-built SnpEff was used for genetic variant annotation and functional impact predictions. The unique variants within the two Cameroonian genomes from our study were identified, and their position in the ORFs as well as their effect were evaluated. The result generated from NUCmer and SnpEff was converted to CSV files, and visualisations were done using R.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Distribution

A total of 172 Cattle were sampled across the three countries. In Cameroon, 57 cattle were sampled from eight farms and one cattle market. In Benin Republic, 55 cattle were sampled from nine farms. In Nigeria, 60 cattle were sampled from two abattoirs. Overall, swabs constituted the largest proportion of sample types collected (53.5%), followed by skin scabs (43.1%) and nodule aspirates (3.4%). In Benin Republic and Nigeria no nodule aspirates was collected. In Cameroon, nodule aspirates were collected from 10 (10.6%) animals (

Table 1). The distribution of pooled fly samples varied across the three countries (

Table 2). Five fly pools each from Nigeria and Cameroon were analysed, while 31 pools of flies from the Benin Republic were analysed.

3.2. PCR Result

An animal was confirmed positive when one of the samples collected from that animal tested positive by PCR. Fourteen animals (14/172, 8.1%) had at least one sample test positive with five of these animals testing positive in more than one sample type. Positive animals were from three farms (3/8) and one cattle market (1/1) in Cameroon, one farm (1/9) in Benin Republic and one abattoir (1/2) in Nigeria. Among the countries studied, Cameroon had the highest positivity rate, with 17 out of 94 samples testing positive (18.1%). In contrast, Nigeria and the Benin Republic showed significantly (χ2=31.4, p<0.001) lower LSDV PCR positivity rates of 0.8% (1/120) and 1.2% (1/83), respectively compared to Cameroon (

Table 3). PCR results also varied by sample type. Skin scabs showed the highest positivity rate of 9.4% (12/128) among the sample types (table 3). However, the association between sample type and PCR positivity was not statistically significant (χ2=3.9, p=0.139). Of the 41 fly pools tested by PCR, only one fly pool (flesh fly pool from Cameroon) tested positive for LSDV by PCR (

Table 2).

3.3. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

Of the 28 samples sequenced, 15 tested positive for LSD by PCR, but 13 of the 28 sequenced samples had reads mapping to LSDV. Among these, two samples exhibited genome completeness exceeding 90% when compared to the reference genome LSDV NI-2490 (NC003027). Notably, one sample with LSDV reads was PCR-negative, although the read count was substantially low, whereas three PCR-positive samples did not yield any LSDV reads through sequencing. The two samples with genome completeness above 90% were collected from Cameroon.

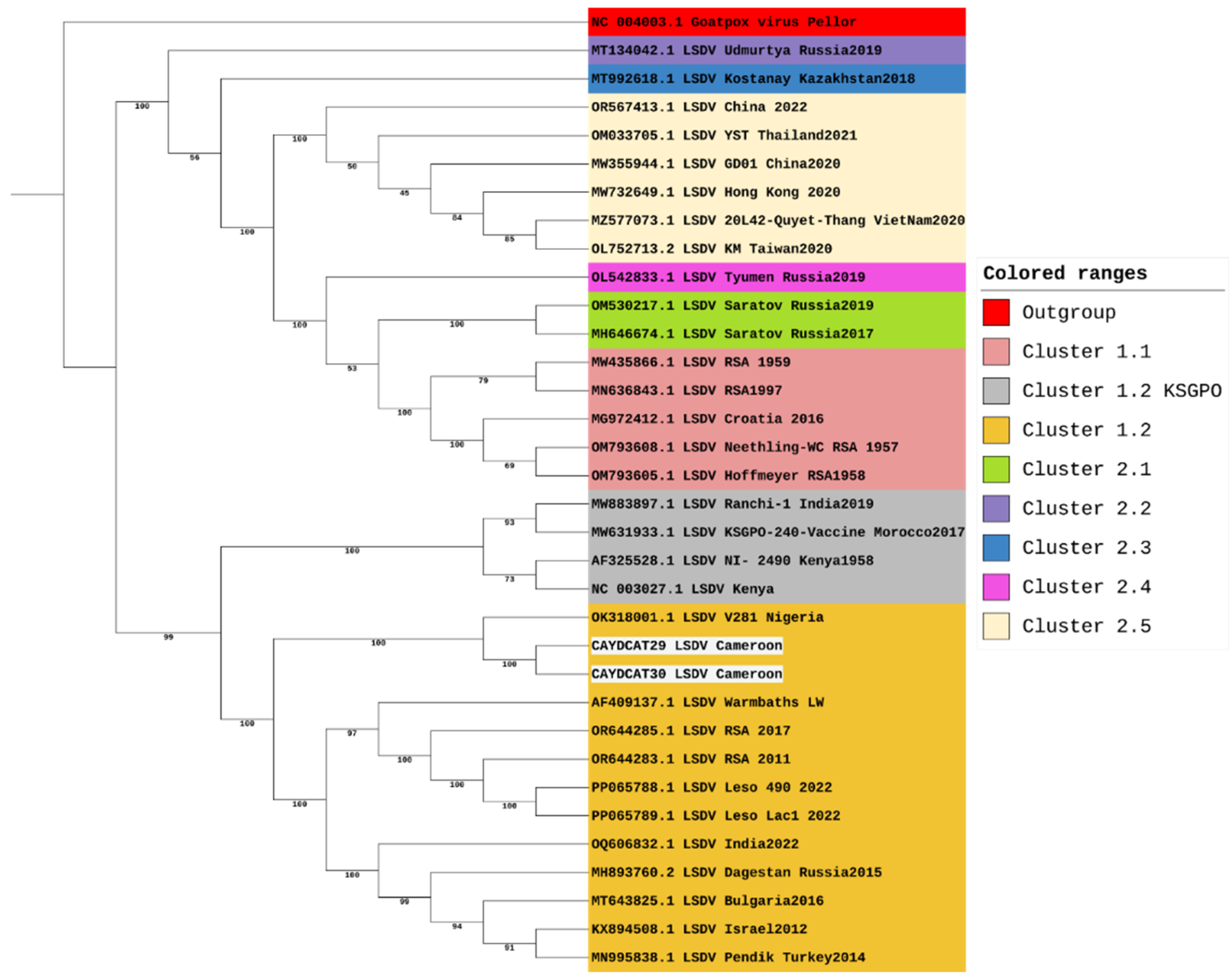

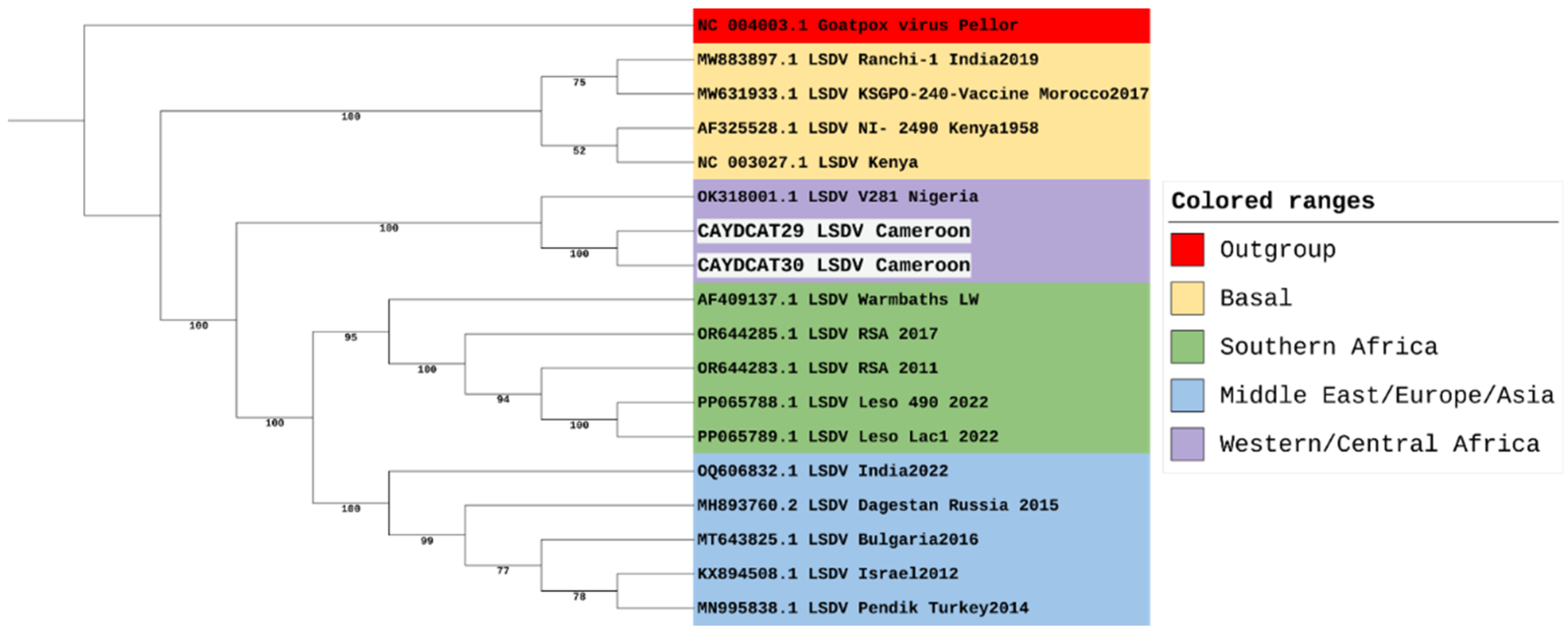

The maximum likelihood tree (

Figure 2) was constructed using 34 sequences, including two from Cameroon (>90% completeness) and 32 from the NCBI virus database. LSDV strains are sorted into 7 clusters, with clusters 1.1 and 1.2 being the classical strains and clusters 2.1 to 2.5 containing vaccine recombinant strains. Phylogenetic analysis shows that the two Cameroon genomes cluster together within cluster 1.2 and are closely related to other African strains but are distantly related to classical strains in cluster 1.1 and vaccine recombinant strains. These two sequences form a clade with the only LSDV strain (whole genome) from Nigeria available on NCBI (OK318001). This shows that the Nigerian strain is the most closely related to the two sequences from this study.

Being the most divergent of the 7 LSDV clusters, a maximum likelihood tree focusing on cluster 1.2 was constructed to focus on its three established sub-lineages (

Figure 3). However, our sequences from Cameroon, together with the sequence from Nigeria, do not all fit into any of the three sub-lineages of cluster 1.2. This suggests that while the LSDV strains from Nigeria and Cameroon might be closely related to the strains from Southern Africa, and some strains from Europe, Asia and the Middle East, these three strains appear slightly distinct from other strains within cluster 1.2. Hence, we suggest that these three strains could belong to a separate sub-lineage and could be tagged the Western/Central African sub-lineage within the LSDV 1.2 cluster.

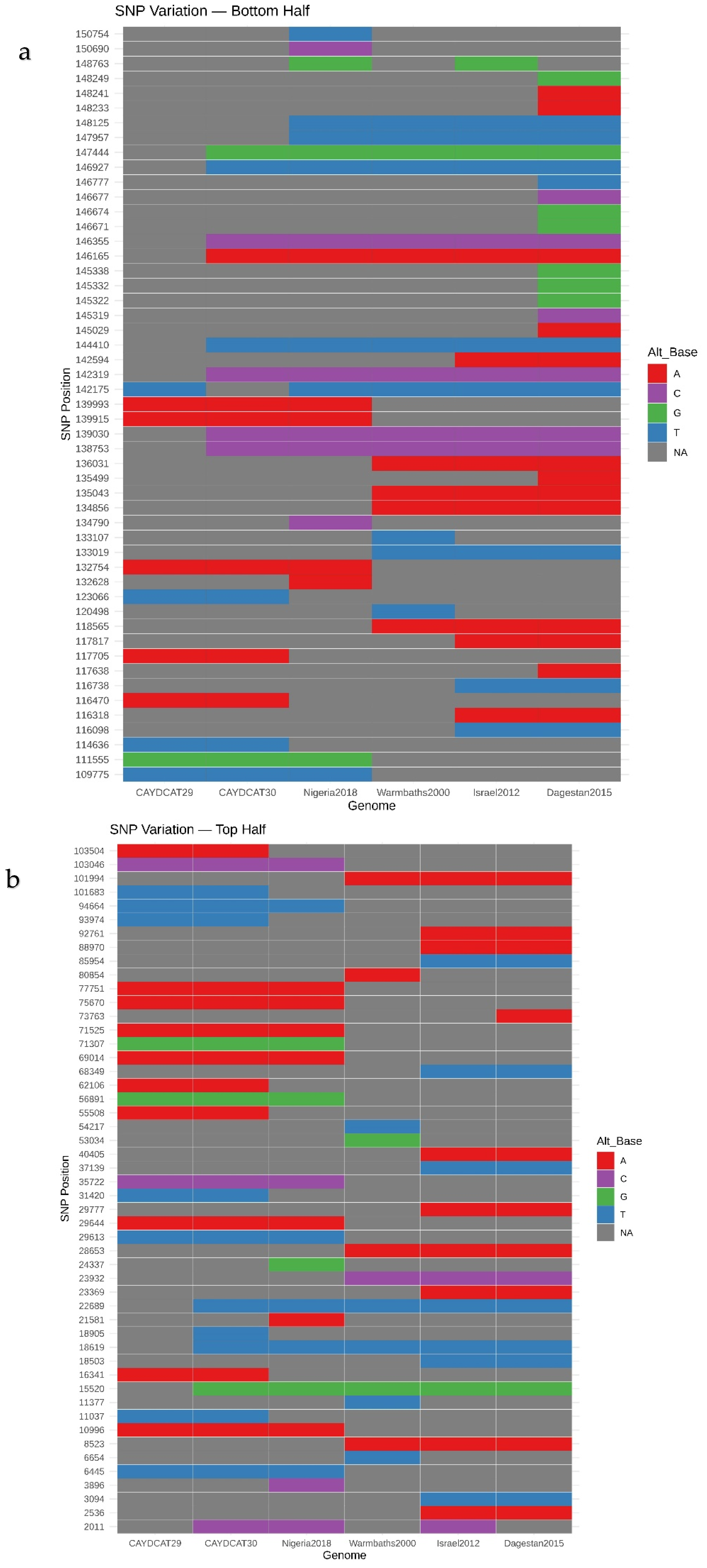

3.4. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Cameroonian LSDV Genomes Reveals SNP and Indel Variations

To characterise the genetic diversity of LSDV strains circulating in Cameroon, two whole genomes from this study (designated CAYDCAT29 and CAYDCAT30) were analysed. These were compared to four representative genomes from established sub-lineages of the LSDV cluster 1.2: Dagestan2015, Warmbaths 2000, Nigeria2018, and Israel2012. All 6 genomes were compared to the LSDV reference genome (NC003027) to obtain variant reports using NUCmer.

Quantification of the single-base substitutions (SNPs), insertions, and deletions in each sequence (

Table 4) revealed that the two newly assembled Cameroonian LSDV genomes displayed relatively low mutations compared to the other 4 reference representatives. CAYDCAT29 showed 124 single-base substitutions, 14 insertions, and 22 deletions, while CAYDCAT30 showed a modestly higher number of substitutions (n = 136), with 24 insertions and 25 deletions. Among the genome representatives, Dagestan2015 showed the highest number of single-base substitutions (n = 147), suggesting a more divergent lineage within cluster 1.2. Warmbaths2000 showed the highest number of insertions (n = 78), while Israel2012 presented the highest number of deletions (n = 45). These differences reflect distinct evolutionary trajectories within the cluster.

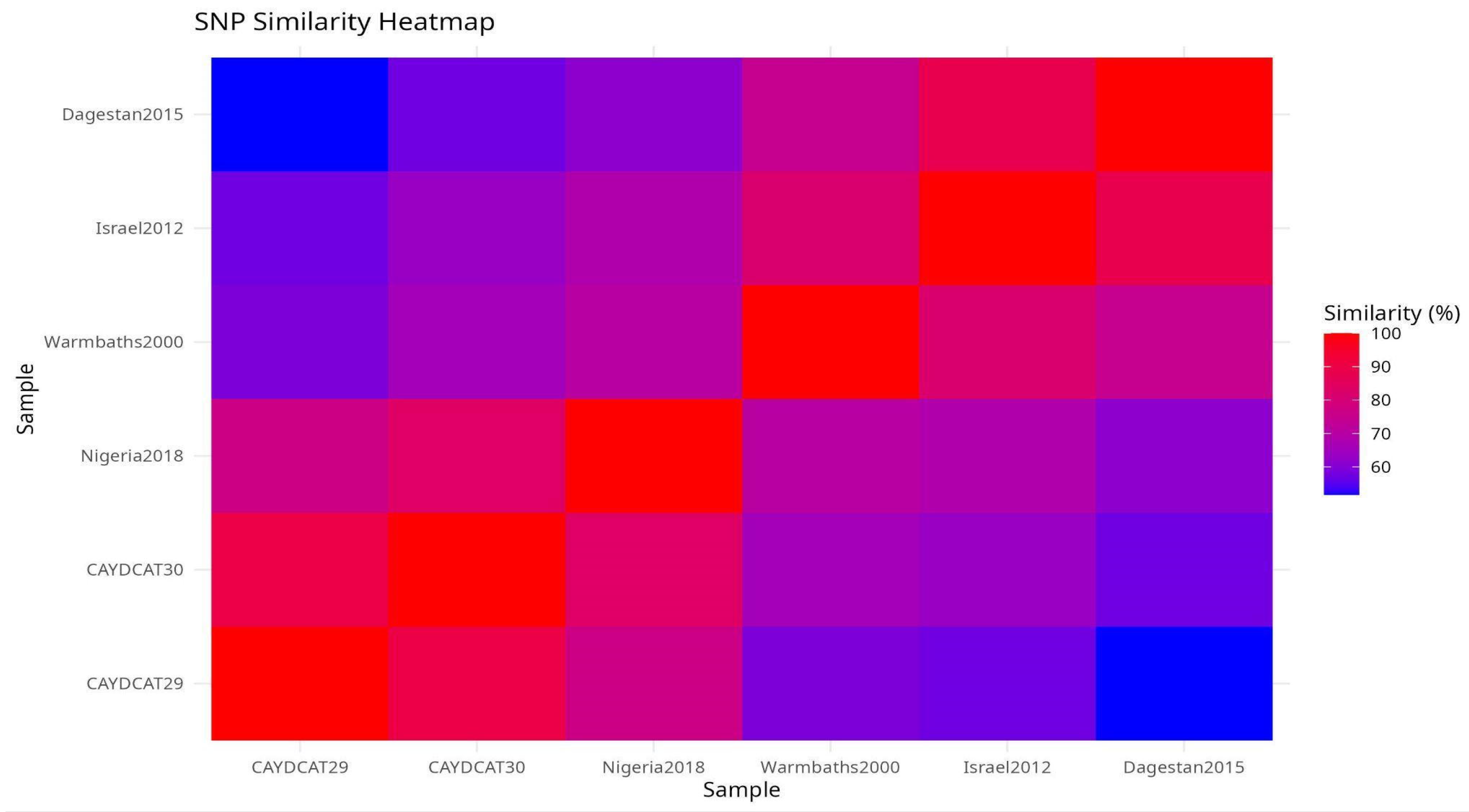

A total of 101 unique SNP positions were identified across the six genomes, spanning both coding and non-coding regions. SNP heatmap plots (

Figure 4a,b) revealed a high degree of conservation between the Cameroonian genomes. CAYDCAT29 and CAYDCAT30 exhibited nearly identical SNP signatures, further supporting their close relationship. Notably, several SNPs were conserved between the Cameroonian LSDV genomes and Nigeria2018, suggesting a shared sub-lineage or recent common ancestor.

To explore overall genomic similarity, we constructed a heatmap (

Figure 5) using the Jaccard similarity coefficient, which quantifies the proportion of shared SNPs relative to the total set of unique SNPs between genome pairs. This approach captures both convergent and divergent SNP signatures across the genomes. CAYDCAT29 and CAYDCAT30 exhibited the highest similarity (>85%), consistent with a shared origin. Both genomes also have close SNP patterns with Nigeria2018 (Jaccard similarity between 75 and 85%), further supporting their placement within a Central/West African subset of LSDV cluster 1.2. In contrast, Warmbaths2000, Israel2012, and especially Dagestan2015 showed lower similarity to the Cameroonian LSDV genomes (Jaccard indices <62%), suggesting more distant evolutionary relationships. These patterns confirm that the Cameroonian strains are genetically distinct but most closely related to Nigeria2018, supporting the hypothesis of regional continuity in virus evolution within cluster 1.2.

3.5. Functional Impact of Genetic Variation in Cameroonian LSDV Genomes

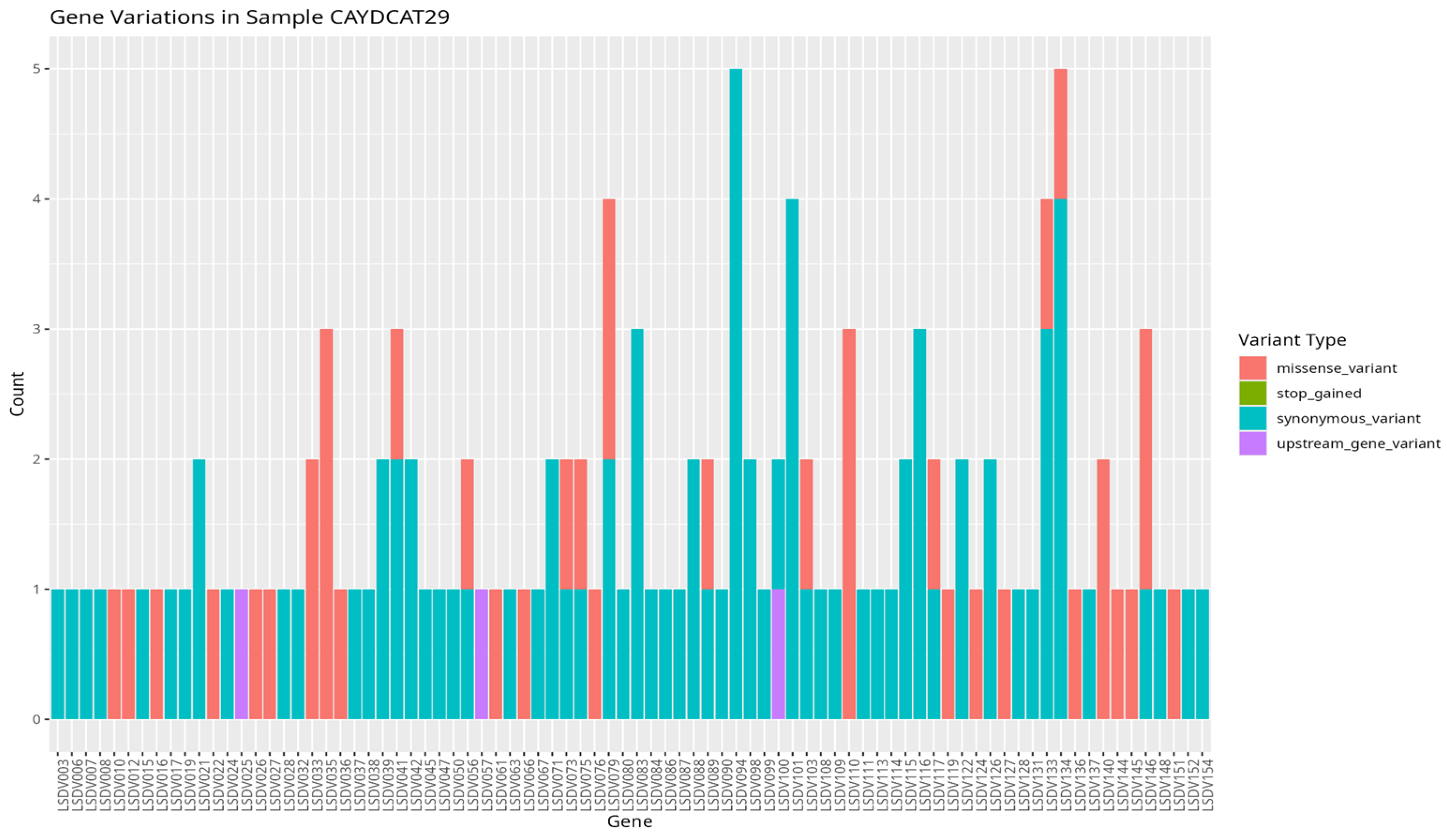

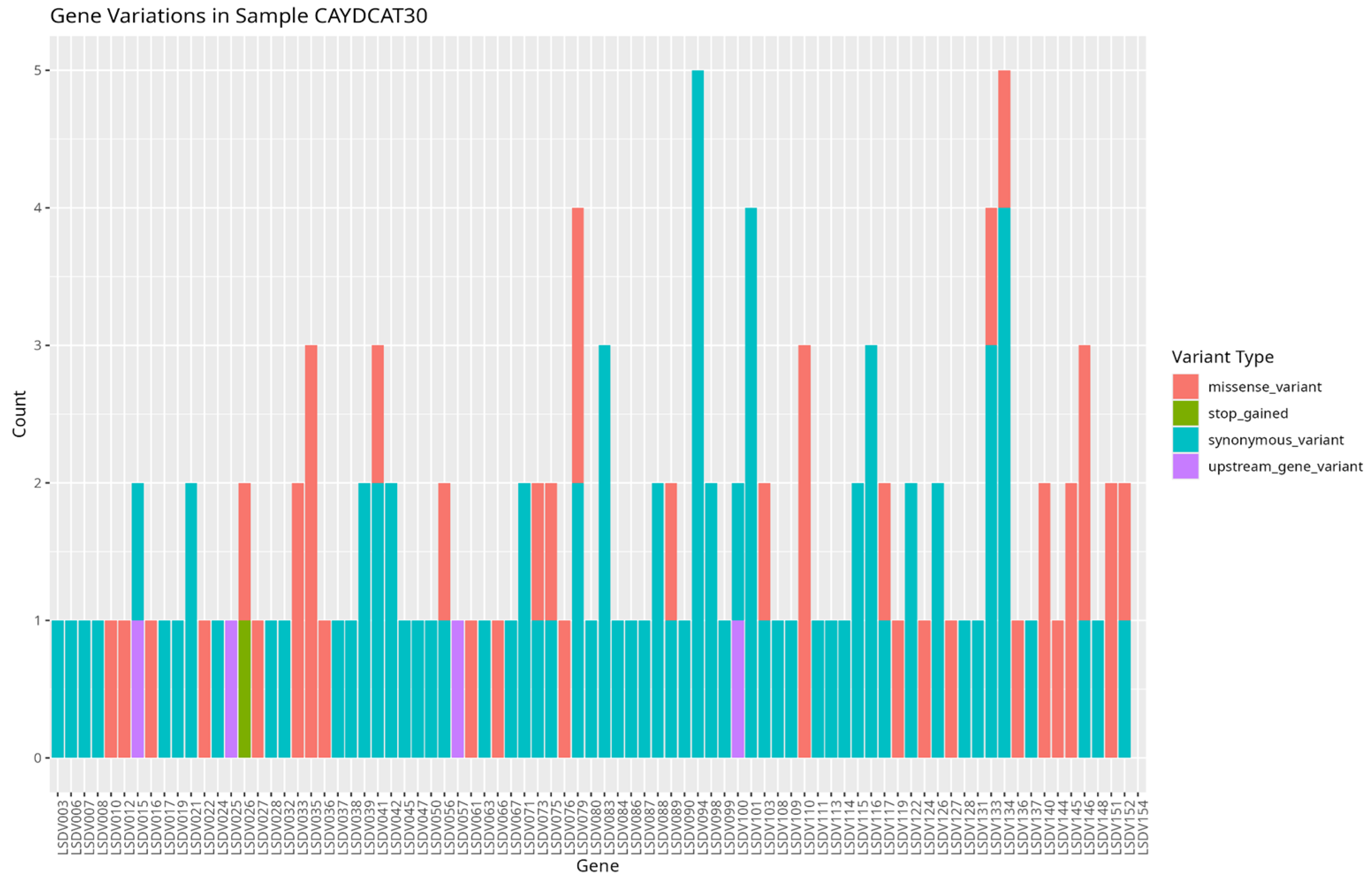

To assess the functional characteristics of the genetic variations in the Cameroonian LSDV genomes, we examined the distribution of mutations across affected genes and their potential functional consequences. A total of 82 genes in CAYDCAT29 and 81 genes in CAYDCAT30 were found to contain at least one sequence variant (

Table 5). Among these, 23 genes in CAYDCAT29 and 25 genes in CAYDCAT30 harboured two or more mutations. Furthermore, 35 genes in CAYDCAT29 and 37 genes in CAYDCAT30 encoded non-synonymous mutations and only one gene, LSDV154, was uniquely mutated in CAYDCAT29, while no genes were uniquely affected in CAYDCAT30. Overall, 126 and 133 mutations were functionally annotated in CAYDCAT29 and CAYDCAT30, respectively. The most prevalent class of coding variation was synonymous substitutions (n = 86 in CAYDCAT29; n = 85 in CAYDCAT30), followed by missense mutations (n = 40 and 43, respectively). Notably, a single stop-gained mutation was observed in CAYDCAT30 but absent in CAYDCAT29. Additionally, both genomes carried a small number of upstream gene variants (n = 3 in CAYDCAT29; n = 4 in CAYDCAT30).

Furthermore, our study identified several genes harbouring missense variants that may influence viral gene expression and immune suppression. Missense variants were observed in genes encoding ankyrin repeat proteins LSDV012 and LSDV145, which have been reported to inhibit interferon-induced proteins, particularly IFIT1, thereby enhancing viral replication [

32]. Similarly, mutations were identified in LSDV144 and LSDV151, which encode kelch-like proteins involved in protein-protein interactions that facilitate immune evasion [

33]. Missense variants were also detected in LSDV140, homologous to poxvirus N1R/p28, which is known to suppress apoptosis and promote viral virulence [

34]. Additionally, the phospholipase-D-like protein LSDV146 plays a role in viral dissemination [

35,

36] also exhibited missense variation.

Among structural proteins, our study identified missense variants in the gene encoding the putative extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) maturation protein LSDV027, which is essential for viral dissemination as inferred from UniProt. Similarly, missense variants were found in the virion core protein genes LSDV041 and LSDV103, which undergo proteolytic processing during the transition from immature virion to mature virion [

26,

33,

37]. Missense variants were also present in LSDV073 and LSDV075, which encode putative viral membrane proteins with putative roles involving viral entry, membrane fusion, and virion assembly [

33].

Several genes encoding viral enzymes also had mutations (missense variants). These mutations can potentially affect viral transcription and replication. Variants were observed in LSDV036 and LSDV119, which encode RNA polymerase subunits and are involved in viral mRNA synthesis [

26]. Missense variations were also present in LSDV079 and LSDV089, which encode mRNA-capping enzyme subunits responsible for ensuring mRNA stability and efficient translation [

38]. Additionally, missense variants were detected in LSDV066, a thymidine kinase essential for nucleotide metabolism and viral replication [

39], and LSDV133, a DNA ligase-like protein that plays a role in genome integrity by repairing and ligating DNA strands [

40].

Our study also identified upstream gene variants in several essential viral genes. Variants were observed in LSDV015, which encodes an IL-18 binding protein known to modulate immune responses by inhibiting IL-18 activity [

41]. Upstream variants were also present in LSDV025, which encodes a serine/threonine kinase involved in viral replication [

42]. Additionally, mutations were found in LSDV057 and LSDV100, which encode a putative virion core protein and an intracellular mature virus membrane protein, respectively, potentially influencing virion assembly and infectivity [

43,

44].

Figure 6.

Gene variation profile in sample CAYDCAT29. Distribution of gene variants across all genes, showing the count of missense_variant, stop_gained, synonymous_variant, and upstream_gene_variant.

Figure 6.

Gene variation profile in sample CAYDCAT29. Distribution of gene variants across all genes, showing the count of missense_variant, stop_gained, synonymous_variant, and upstream_gene_variant.

Figure 7.

Gene variation profile in sample CAYDCAT30. Distribution of gene variants across all genes, showing the count of missense_variant, stop_gained, synonymous_variant, and upstream_gene_variant.

Figure 7.

Gene variation profile in sample CAYDCAT30. Distribution of gene variants across all genes, showing the count of missense_variant, stop_gained, synonymous_variant, and upstream_gene_variant.

4. Discussion

This study revealed LSDV in cattle from Benin Republic, Cameroon, and Nigeria. Despite low percentage positivity, we added two new LSDV genomes in the global database and identified a potentially new West and Central Africa sub-lineage of the virus. Only the Nigerian strain of LSDV in the GenBank is closely related to the sequences from this study.

The genomic analysis identified a new subgroup of Cameroonian and Nigerian strains within the classic LSDV cluster 1.2, suggesting a unique evolutionary sub-lineage specific to West and Central Africa [

45]. Recent studies have revealed increased diversity within the LSDV cluster 1.2 [

46]. Furthermore, several strains within the 1.2 cluster, such as the Pendik Turkey strain in 2014/2015 [

8] and the Evros strain in Greece and Turkey [

47], have been attributed to various outbreaks across Eurasia and South Asia. Moreover, historical analysis suggests that cluster 1.1 strains have been displaced by cluster 1.2 strains in South Africa, with an estimated substitution rate of 7.4 × 10-6 substitutions/site/year [

48]. The rapid pace of LSDV mutations supports the diversity of sub-clusters within the 1.2 cluster, and this could mean changes in the virulence of the pathogen, transmission dynamics, or immune response in affected cattle populations. This has great implications for vaccine effectiveness and the ability of several regions to curb outbreak cases. For this reason, we suggest the need for polyvalent vaccines or regionally-based vaccines coupled with effective control of transboundary cattle movement. Our findings also highlight the value of whole-genome sequencing in uncovering regional diversity and the need to revisit current classification strategies, which put underrepresented African strains into consideration. By doing so, better genomic and genetic information can be gathered to support the development of effective vaccines.

The findings from our study further revealed a relatively low number of substitutions and indels among the Cameroonian and Nigerian LSDV genomes, suggesting sgenomic conservation and evolutionary stability within this regional sub-lineage. Conversely, marked divergence from strains in Europe, Asia, and Southern Africa reflects the continuous evolution of the strains in these regions. For example, multiple strains from South Africa belong to clusters 1.1 and 1.2 [

49], and LSDV strains from Russia, India, and China have representatives across multiple LSDV clusters [

46,

50,

51]. This could explain the relatively low report of mortality and morbidity associated with LSDV in the western and central African region [

52] due to better adaptation among host animals as opposed to the recurrent outbreaks within Eurasia and Asia [

2,

53], where recent outbreaks, especially in Southeast Asia, have shown unusually high mortality rates [

54]. However, given that this study was a one off, with limited full genomes assembled, there is a need for continued surveillance in Western and Central Africa to detect the true epidemiological picture of the disease in this region, as well as the need for broader African genomic datasets to better define LSDV’s global diversity and inform phylogeographic analyses.

The identification of non-synonymous mutations in several LSDV genes, particularly those involved in immune modulation and antigen presentation, carries important implications for vaccine design. Key mutated genes identified in this study, including LSDV012, LSDV144, LSDV145, and LSDV151, encode ankyrin repeats and kelch-like proteins. These proteins are known to suppress host immune factors, such as interferon-induced proteins like IFIT1, facilitating immune evasion [

32]. Similar mutations have been observed in other LSDV strains. Unique Kenyan-like LSDV strains circulating in India exhibited truncated versions of kelch-like proteins encoded by LSD_019 and LSD_144, which may influence virulence and host range [

55]. Supporting this, a functional study in sheeppox virus demonstrated that deletion of the kelch-like gene SPPV-019, a homolog of LSDV019, led to marked in vivo attenuation, with infected sheep exhibiting dramatically reduced clinical symptoms, viremia, and virus shedding, showing the role of kelch-like genes in regulating capripoxvirus virulence and immune modulation [

56]. This could imply that strains carrying this truncation or deletion in the kelch protein gene are relatively less virulent. Moreover, the role of kelch protein deletion in reducing virulence of the virus makes it important in vaccine design. A recent study demonstrated that vaccinia virus strains lacking the C2 kelch-like gene not only exhibited attenuation in vivo but also induced a stronger CD8⁺ T cell memory response and improved protection against viral challenge, compared to control strains retaining the gene [

57]. These findings highlight the functional significance of kelch-domain proteins in immune modulation and virulence, and their deletion offers a promising strategy for the design of live attenuated vaccines that are both safer and more immunogenic.

Additionally, the study demonstrated that the Cameroonian strains do not fall into established sub-lineages, indicating genomic divergence from strains used for the development of vaccines such as the Neethling strain [

58]. If the immunodominant regions of the virus, especially within the envelope proteins and core virion proteins, have accumulated substantial mutations, current vaccines may offer reduced protection. For instance, LSDV027, a gene encoding the extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) maturation protein, is key for virus dissemination and immune recognition [

59]. Experimental data from vaccinia virus provides further support for this concern. A study by [

60] found that the introduction of a single amino acid mutation in the B5R EEV envelope glycoprotein (WR.c3) induced lower titers of antibodies, suggesting that alterations in EEV surface proteins may impair humoral immune responses. This further supports the need for polyvalent vaccines or regionally-based vaccines coupled with effective control of transboundary cattle movement.

Missense mutations identified in key virulence-associated genes (LSDV140 and LSDV146) suggest potential modulation of the virus's pathogenic behaviour. The LSDV140 gene, a homologue of the N1R/p28 protein found in other poxviruses, is known to suppress host cell apoptosis, thereby promoting viral survival [

34]. Mutations in this gene may either enhance or impair its anti-apoptotic function, potentially influencing the severity and duration of infection. Similarly, LSDV146, which encodes a phospholipase-D-like protein involved in viral dissemination, could influence the efficiency of intra-host spread [

35,

36]. Changes in this gene may affect how extensively the virus invades host tissues, thereby shaping the clinical presentation of the disease. Collectively, these mutations may make the strain more virulent. A strain that replicates more rapidly and suppresses immune detection may elicit a weaker immune response while also causing more severe disease, thereby complicating efforts to achieve effective immunisation and long-term protection. It should however, be noted that while all these mutations could potentially affect the virulence of the virus or its immunogenic activities, functional studies are required to directly link these mutations to phenotypic changes.

Most positive samples were skin scabs, with the lowest positivity seen in oral/nasal swabs. This adds to the report that skin scabs could be the most reliable sample for LSDV detection [

7,

61]. This implies that while it would be easy to collect oral/nasal swabs, their lower yield suggests they should be complemented with other sample types in outbreak investigations.

SDV was also detected in flesh flies (Sarcophaga spp). Although various arthropods have been linked to LSDV transmission, this is the first report of LSDV in flesh flies. Due to their feeding on exposed wounds [

62], it suggests other arthropods might also mechanically transmit LSD. Therefore, comprehensive vector control strategies are essential to prevent LSDV spread, especially in regions where arthropods are primary vectors, during disease outbreaks.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study identified further divergence within the 1.2 cluster with the possibility of a western/central African sub-lineage. Moreover, the presence of high-impact mutations in genes necessary for viral replication and immunogenicity suggests the ability of these Cameroonian strains to evade host immune responses and the limitations of current vaccines in this region. Our study also identified flesh flies as a novel arthropod involved in LSDV transmission. We, therefore, recommend the development of polyvalent vaccines that take into consideration the peculiarities in the antigenicity of the different LSDV strains circulating in the different regions of the world where LSDV outbreaks have been recorded. It is important to note that sampling in Nigeria was done in one southwestern state and in abattoirs alone. Therefore, the result from this study might not reflect the true picture of the epidemiology of LSDV in Nigeria.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.; methodology, A.H., validation, A.S. and O.O., C.H. and A.H.; formal analysis, J.F., O.O., A.A., O.A., A.S., F.S. and H.S.; investigation, J.F., M.P., U.F., A.S., O.A., O.O., A.A. and A.H.; resources, C.B., F.B., C.H. and AH.; data curation, J.F., O.A. and O.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F., H.S., O.O. and O.A.; writing—review and editing, C.B., F.B., C.H. and A.H.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, C.H. and A.H.; project administration, C.B., F.B., C.H. and A.H.; funding acquisition, C.B, F.B., and A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding support for this study was provided by the USDA GPADZ project and LifeStock International.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Veterinary Research Institute, Vom, Nigeria (AEC/02/170/24).

Informed Consent Statement

This is not applicable as our study did not involve human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

sequences derived from this study has been submitted to GenBank under the ascension number PV963838 and PV963839 with Bioproject PRJNA1290111

Acknowledgments

we acknowledge the technical and laboratory support provided by IGH staff.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Meaning |

| LSDV |

Lumpy Skin Disease Virus |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic Acid |

| qPCR |

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR |

| CT |

Cycle Threshold |

| EEV |

Extracellular Enveloped Virus |

| ORF |

Open Reading Frame |

| SNP |

Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism |

| Indel |

Insertion or Deletion Mutation |

| NCBI |

National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| MAFFT |

Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform |

| IQTREE2 |

Efficient software for phylogenomic inference |

| iTOL |

Interactive Tree of Life |

| BWA |

Burrows-Wheeler Aligner |

| NUCmer |

Nucleotide MUMmer (alignment software) |

| SnpEff |

SNP Effect Predictor |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| MUMmer |

Maximal Unique Match aligner |

| AWK |

A pattern scanning and processing language |

| VirCapSeq-VERT |

Virus Capture Sequencing for Vertebrates |

| IGH |

Institute of Genomics and Global Health |

References

- L. Khan, “A comprehensive review on lumpy skin disease,” Pure and Applied Biology, vol. 13, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Jyoti, S. S. Jyoti, S. Karki, R. Nepal, and K. Kaphle, “A Review of Global Epidemiology of Lumpy Skin Disease, its Economic Impact, and Control Strategies,” Authorea (Authorea), Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Adedeji et al., “Recurrent outbreaks of lumpy skin disease and its economic impact on a dairy farm in Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria,” Niger Vet J, vol. 38, pp. 151–158, Jun. 2017.

- W. Modethed et al., “An evaluation of financial losses due to lumpy skin disease outbreaks in dairy farms of northern Thailand,” Front Vet Sci, vol. 11, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. Molla, M. C. M. W. Molla, M. C. M. de Jong, G. Gari, and K. Frankena, “Economic impact of lumpy skin disease and cost effectiveness of vaccination for the control of outbreaks in Ethiopia,” Prev Vet Med, vol. 147, pp. 100–107, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sprygin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Epidemiological characterization of lumpy skin disease outbreaks in Russia in 2016,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 65, pp. 1514–1521, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Li et al., “Quantitative real-time PCR detection and analysis of a lumpy skin disease outbreak in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China,” Front Vet Sci, vol. 9, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Şevik and M. Doğan, “Epidemiological and Molecular Studies on Lumpy Skin Disease Outbreaks in Turkey during 2014-2015,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 64, pp. 1268–1279, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. Adedeji, O. B. J. Adedeji, O. B. Akanbi, J. A. Adole, N. C. Chima, and M. Baje, “Outbreak of lumpy skin disease in a dairy farm in Keffi, Nasarawa State, Nigeria,” Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, vol. 16, p. 80, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Machado, F. G. Machado, F. Korennoy, J. Alvarez, C. Picasso-Risso, A. Perez, and K. VanderWaal, “Mapping changes in the spatiotemporal distribution of lumpy skin disease virus,” bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory), Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Moudgil, J. G. Moudgil, J. Chadha, L. Khullar, S. Chhibber, and K. Harjai, “Lumpy skin disease: Insights into current status and geographical expansion of a transboundary viral disease,” Microb Pathog, vol. 186, p. 106485, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. CHIHOTA, L. F. M. CHIHOTA, L. F. RENNIE, R. P. KITCHING, and P. S. MELLOR, “Mechanical transmission of lumpy skin disease virus by Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae),” Epidemiol Infect, vol. 126, pp. 317–321, Jun. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Pâslaru, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Putative roles of mosquitoes (Culicidae) and biting midges (Culicoides spp.) as mechanical or biological vectors of lumpy skin disease virus,” Med Vet Entomol, vol. 36, pp. 381–389, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Paslaru et al., “Potential mechanical transmission of Lumpy skin disease virus (LSDV) by the stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) through regurgitation and defecation,” Current Research in Insect Science, vol. 1, p. 100007, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Gubbins, “Using the basic reproduction number to assess the risk of transmission of lumpy skin disease virus by biting insects,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 66, pp. 1873–1883, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. S. M. TUPPURAINEN et al., “Mechanical transmission of lumpy skin disease virus by Rhipicephalus appendiculatus male ticks,” Epidemiol Infect, vol. 141, pp. 425–430, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Lubinga, E. S. M. J. C. Lubinga, E. S. M. Tuppurainen, J. A. W. Coetzer, W. H. Stoltsz, and E. H. Venter, “Transovarial passage and transmission of LSDV by Amblyomma hebraeum, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus and Rhipicephalus decoloratus,” Exp Appl Acarol, vol. 62, pp. 67–75, Jun. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Shumilova, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “A Recombinant Vaccine-like Strain of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Causes Low-Level Infection of Cattle through Virus-Inoculated Feed,” Pathogens, vol. 11, p. 920, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Faris, K. N. Faris, K. El-Bayoumi, M. El-Tarabany, and E. Ramadan Kamel, “Prevalence and Risk Factors for Lumpy Skin Disease in Cattle and Buffalo under Subtropical Environmental Conditions,” Adv Anim Vet Sci, vol. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Zewdie, B. G. Zewdie, B. Mammo, E. Gelaye, B. Getachew, and B. Bayssa, “Isolation, Molecular Characterisation and Vaccine Effectiveness Study of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus in Selected Diary Farms of Central Ethiopia,” J Biol Agric Healthc, vol. 9, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Gera, E. Klement, E. Khinich, Y. Stram, and N. Y. Shpigel, “Comparison of the efficacy of Neethling lumpy skin disease virus and x10RM65 sheep-pox live attenuated vaccines for the prevention of lumpy skin disease – The results of a randomized controlled field study,” Vaccine, vol. 33, pp. 4837–4842, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Klement, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Neethling vaccine proved highly effective in controlling lumpy skin disease epidemics in the Balkans,” Prev Vet Med, vol. 181, p. 104595, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sprygin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Analysis and insights into recombination signals in lumpy skin disease virus recovered in the field,” PLoS One, vol. 13, p. e0207480, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ma, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Genomic characterization of lumpy skin disease virus in southern China,” Transbound Emerg Dis, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Byadovskaya, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “The changing epidemiology of lumpy skin disease in Russia since the first introduction from 2015 to 2020,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 69, pp. e2551–e2562, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Tulman, C. L. R. Tulman, C. L. Afonso, Z. Lu, L. Zsak, G. F. Kutish, and D. L. Rock, “Genome of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus,” J Virol, vol. 75, pp. 7122–7130, Jun. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Krotova, O. Byadovskaya, I. Shumilova, A. van Schalkwyk, and A. Sprygin, “An in-depth bioinformatic analysis of the novel recombinant lumpy skin disease virus strains: from unique patterns to established lineage,” BMC Genomics, vol. 23, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Ochwo et al., “Molecular detection and phylogenetic analysis of lumpy skin disease virus from outbreaks in Uganda 2017–2018,” BMC Vet Res, vol. 16, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Sudhakar, N. S. B. Sudhakar, N. Mishra, S. Kalaiyarasu, S. K. Jhade, and V. P. Singh, “Genetic and phylogenetic analysis of lumpy skin disease viruses (LSDV) isolated from the first and subsequent field outbreaks in India during 2019 reveals close proximity with unique signatures of historical Kenyan NI-2490/Kenya/KSGP-like field strains,” Transbound Emerg Dis, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Kapoor et al., “Validation of the VirCapSeq-VERT system for differential diagnosis, detection, and surveillance of viral infections,” J Clin Microbiol, vol. 62, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mazloum, A. Van Schalkwyk, S. Babiuk, E. Venter, D. B. Wallace, and A. Sprygin, “Lumpy skin disease: history, current understanding and research gaps in the context of recent geographic expansion,” Front Microbiol, vol. 14, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Xie et al., “A poxvirus ankyrin protein LSDV012 inhibits IFIT1 in a host-species-specific manner by compromising its RNA binding ability,” PLoS Pathog, vol. 21, p. e1012994, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Schlosser-Perrin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Constitutive proteins of lumpy skin disease virion assessed by next-generation proteomics,” J Virol, vol. 97, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Nicholls and T. A. Gray, “Cellular source of the poxviral N1R/p28 gene family,” Virus Genes, vol. 29, pp. 359–364, Jun. 2004. [CrossRef]

- T.-C. Sung, “Mutagenesis of phospholipase D defines a superfamily including a trans-Golgi viral protein required for poxvirus pathogenicity,” EMBO J, vol. 16, pp. 4519–4530, Jun. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Husain and, B. Moss, “Similarities in the Induction of Post-Golgi Vesicles by the Vaccinia Virus F13L Protein and Phospholipase D,” J Virol, vol. 76, pp. 7777–7789, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, J. X. Yuan, J. Dong, Z. Xiang, Q. Zhang, P. Tao, and A. Guo, “A Genome-Wide Screening of Novel Immunogenic TrLSDV103 Protein of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus and Its Application for DIVA,” The FASEB Journal, vol. 39, Jun. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Abolnik, “Comparative sequence analysis of the South African vaccine strain and two virulent field isolates of Lumpy skin disease virus,” Arch Virol, vol. 148, pp. 1335–1356, 2003. [CrossRef]

- B. Wallace and G. J. Viljoen, “Importance of thymidine kinase activity for normal growth of lumpy skin disease virus (SA-Neethling),” Arch Virol, vol. 147, pp. 659–663, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Suwankitwat, T. Deemagarn, K. Bhakha, T. Songkasupa, P. Lekcharoensuk, and Pi. Arunvipas, “Monitoring of genetic alterations of lumpy skin disease virus in cattle after vaccination in Thailand,” J Anim Sci Technol, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Reading and G. L. Smith, “Vaccinia Virus Interleukin-18-Binding Protein Promotes Virulence by Reducing Gamma Interferon Production and Natural Killer and T-Cell Activity,” J Virol, vol. 77, pp. 9960–9968, Jun. 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Abduljalil, H. A. J. M. Abduljalil, H. A. Al-Madhagi, A. A. Elfiky, and M. M. AlKhazindar, “Serine/threonine kinase of Mpox virus: computational modeling and structural analysis,” J Biomol Struct Dyn, vol. 42, pp. 12434–12445, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Carter, M. C. Carter, M. Law, M. Hollinshead, and G. L. Smith, “Entry of the vaccinia virus intracellular mature virion and its interactions with glycosaminoglycans,” J Gen Virol, vol. 86, pp. 1279–1290, Jun. 2005. [CrossRef]

- X. Meng, A. X. Meng, A. Embry, D. Sochia, and Y. Xiang, “Vaccinia Virus A6L Encodes a Virion Core Protein Required for Formation of Mature Virion,” J Virol, vol. 81, pp. 1433–1443, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. Haga et al., “Sequencing and Analysis of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Whole Genomes Reveals a New Viral Subgroup in West and Central Africa,” Viruses, vol. 16, p. 557, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Breman, A. C. Breman, A. Haegeman, N. Krešić, W. Philips, and N. De Regge, “Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Genome Sequence Analysis: Putative Spatio-Temporal Epidemiology, Single Gene versus Whole Genome Phylogeny and Genomic Evolution,” Viruses, vol. 15, p. 1471, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- I. Agianniotaki et al., “Lumpy skin disease outbreaks in Greece during 2015–16, implementation of emergency immunization and genetic differentiation between field isolates and vaccine virus strains,” Vet Microbiol, vol. 201, pp. 78–84, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Van Schalkwyk, O. Byadovskaya, I. Shumilova, D. B. Wallace, and A. Sprygin, “Estimating evolutionary changes between highly passaged and original parental lumpy skin disease virus strains,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 69, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- van, Schalkwyk; et al. , “Potential link of single nucleotide polymorphisms to virulence of vaccine-associated field strains of lumpy skin disease virus in South Africa,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 67, pp. 2946–2960, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. V Saltykov, A. A. Y. V Saltykov, A. A. Kolosova, N. N. Filonova, A. N. Chichkin, and V. A. Feodorova, “Genetic Evidence of Multiple Introductions of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus into Saratov Region, Russia,” Pathogens, vol. 10, p. 716, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Krotova, A. Mazloum, O. Byadovskaya, and A. Sprygin, “Phylogenetic analysis of lumpy skin disease virus isolates in Russia in 2019-2021,” Arch Virol, vol. 167, pp. 1693–1699, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Atai et al., “Epidemiological features of lumpy skin disease outbreaks amongst herds of cattle in Bokkos, north-central Nigeria,” Sokoto Journal of Veterinary Sciences, vol. 19, pp. 81–88, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. R. Khan et al., “A review: Surveillance of lumpy skin disease (LSD) a growing problem in Asia,” Microb Pathog, vol. 158, p. 105050, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Wilhelm and M. P. Ward, “The Spread of Lumpy Skin Disease Virus across Southeast Asia: Insights from Surveillance,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 2023, p. e3972359, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Genomic characterization of Lumpy Skin Disease virus (LSDV) from India: Circulation of Kenyan-like LSDV strains with unique kelch-like proteins,” Acta Trop, vol. 241, p. 106838, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Balinsky et al., “Sheeppox Virus Kelch-Like Gene SPPV-019 Affects Virus Virulence,” J Virol, vol. 81, pp. 11392–11401, Jul. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R.-Y. Zhang, M. A. R.-Y. Zhang, M. A. Pallett, J. French, H. Ren, and G. L. Smith, “Vaccinia virus BTB-Kelch proteins C2 and F3 inhibit NF-κB activation,” Journal of General Virology, vol. 103, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Shumilova et al., “An Attenuated Vaccine Virus of the Neethling Lineage Protects Cattle against the Virulent Recombinant Vaccine-like Isolate of the Lumpy Skin Disease Virus Belonging to the Currently Established Cluster 2.5,” Vaccines (Basel), vol. 12, p. 598, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Smith, A. G. L. Smith, A. Vanderplasschen, and M. Law, “The formation and function of extracellular enveloped vaccinia virus,” Journal of General Virology, vol. 83, pp. 2915–2931, Jun. 2002. [CrossRef]

- I. GURT, I. I. GURT, I. ABDALRHMAN, and E. KATZ, “Pathogenicity and immunogenicity in mice of vaccinia viruses mutated in the viral envelope proteins A33R and B5R,” Antiviral Res, vol. 69, pp. 158–164, Jul. 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Sudhakar et al., “Lumpy skin disease (LSD) outbreaks in cattle in Odisha state, India in 19: Epidemiological features and molecular studies,” Transbound Emerg Dis, vol. 67, pp. 2408–2422, Jun. 2020. 20 August. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Sherman, “Wound Myiasis in Urban and Suburban United States,” Arch Intern Med, vol. 160, pp. 2004–2014, Jun. 2000. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).