1. Introduction

Senecavirus A (SVA), also known as Seneca Valley virus, is a non-enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the family

Picornaviridae [

1]. It is the sole member of the genus

Senecavirus. The SVA genome is approximately 7.2 kb in length and encodes a polyprotein that is processed into four structural proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4) and eight non-structural proteins. SVA was first identified in 2002 as a contaminant in cell culture media and considered a harmless virus [

2,

3].

Since its initial discovery, retrospective analyses have revealed that SVA had been silently circulating in North American swine populations as early as the late 1980s. The virus was sporadically detected in various clinical samples between 1988 and 2005, though its pathogenic role was unclear at the time. A 2007 case in Canada, where vesicular lesions were observed in pigs transported to the United States, raised suspicions about SVA as a potential vesicular disease agent. Similarly, an isolated case in Indiana, USA, in 2012, also linked SVA to vesicular symptoms. However, it was not until large-scale outbreaks in Brazil (2014) and the United States (2015) that SVA was recognized as an emerging pathogen responsible for vesicular disease in swine. The virus was soon identified in several other countries, including the People’s Republic of China (PROC), Colombia, and Thailand, demonstrating its potential for global spread [

3,

5,

6,

8,

9,

10]. These outbreaks, particularly in Brazil, were associated not only with vesicular lesions in pigs but also with epidemic transient neonatal losses (ETNL), characterized by high mortality in neonatal piglets.

In the USA, SVA has circulated in swine populations for over 30 years, with serological studies confirming its persistence[

1]. The clinical signs of SVA infection, including lethargy, anorexia, fever, lameness, and the presence of vesicles on the snout, oral cavity, and coronary band, are indistinguishable from those of other vesicular diseases, including FMD, swine vesicular disease (SVD), vesicular stomatitis (VS), and vesicular exanthema of swine (VES)[

4,

8,

9].

Molecular epidemiology studies have reclassified SVA strains into distinct phylogenetic clades, with more recent strains displaying increased pathogenicity compared to historical isolates. The widespread circulation of SVA and its ability to induce lesions indistinguishable from those caused by foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) pose significant challenges to veterinary diagnostics and disease control. In non-FMD-endemic regions such as Taiwan, where strict surveillance measures are in place to maintain FMD-free status, the presence of SVA as a vesicular disease agent highlights the importance of continued monitoring and investigation into its epidemiology and genetic characteristics.

SVA was first isolated from blood-contaminated effluent collected from a truck used to transport pig carcasses to a rendering plant in 2006. However, the first clinical detection of SVA in Taiwan occurred in 2012, when a contracted veterinarian at a farrow-to-finish swine farm in Hualien County reported suspected vesicular lesions on the coronary bands of finisher swine to the Local Animal Disease Inspection Authority (LADIA). Samples were collected by veterinarians from LADIA and submitted to the Veterinary Research Institute (VRI) under the Ministry of Agriculture in Taiwan for testing. All samples tested negative for FMD, SVD, VS, and VES, but SVA was identified. Subsequently, SVA was isolated from two clinical cases of pigs with vesicular lesions in Taiwan. In 2018, a veterinary meat inspector at an abattoir in Tainan City also observed vesicular lesions in swine in lairage and reported them to the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Agency. In 2020, the owner of a farrow-to-finish swine farm in Tainan City also reported vesicular lesions in finisher swine to the LADIA. Samples from both cases were collected by veterinarians of LADIA and sent to the VRI for testing for FMD, SVD, VS, VES, and SVA. SVA was isolated from these samples, while agents of other vesicular diseases were not detected and these diseases ruled out. Although SVA has not been associated with significant economic losses to date, its emergence as a vesicular disease pathogen that results in clinical signs almost identical to FMD highlights the need for enhanced surveillance and understanding of its epidemiology[

4].

Among vesicular diseases of swine, foot and mouth disease (FMD) is prominent due to its highly contagious nature and devastating economic consequences, posing significant threats to the swine industry[

10]. After more than 23 years of concerted effort, Taiwan achieved FMD-free status without vaccination for the Taiwan, Penghu, and Matsu regions in 2020. To maintain this status, all vesicular disease cases in swine must be treated as suspected FMD until confirmed otherwise through laboratory testing[

11]. This underscores the critical importance of understanding the epidemiology of the emerging vesicular disease pathogen, SVA, in Taiwan.

However, there is limited information on the prevalence and genetic characteristics of SVA in Taiwanese swine population. Establishing baseline epidemiological and phylogenetic data for SVA is essential for improving understanding of its infection dynamics and assessing its potential impact on the swine industry[

12].

To address these gaps, this study was designed to: investigate the phylogenetic and epidemiological characteristics of SVA in Taiwan by determining the animal level and farm level seroprevalence of SVA in swine across the country; and characterize the genetic profile of Taiwanese SVA isolates. By comparing these isolates with those from other countries, this study seeks to provide critical insights of the epidemiology of SVA in Taiwan and support the development of effective surveillance and control strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Samples archived from previous investigations of cases of vesicular disease were also included in this study for sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. These samples had all been confirmed, at the time of collection, to be negative for FMD, SVD, VS and VES. These archived samples included vesicular epithelial samples collected from cases of vesicular lesions in finisher pigs aged 20–26 weeks in Taiwan in 2012, 2018, and 2020. Additionally, a 2006 strain (ID: HC061119) was isolated from blood-contaminated effluent collected from a truck used for transporting pig carcasses to a rendering plant. Two SVA isolates from 2021 and 2022 were also obtained from oral swab samples collected from swine that had initially tested positive for FMDV NSP antibodies in a separate FMD surveillance program. These FMD test results were subsequently confirmed as false positives based on negative results in virus neutralization tests (VNT) and nucleic acid detection for FMDV. Specifically, one strain from 2021 (ID: 1102577) was isolated from oral swabs collected from 20–26-week-old pigs in a farm in Tainan City, and one strain from 2022 (ID: 1111570) was isolated from oral swabs collected from a 20-week-old pig in a farm in Pingtung County. Additionally, another strain from 2022 (ID: 1111388) was isolated from lymph node tissue collected from a dead 8-week-old pig from a farm in Pingtung County. According to records from the veterinarian of local animal disease inspection agency, this pig had exhibited agonal respiration (gasping) prior to death. Testing conducted at the VRI identified PRRSV and SVA from the collected tissues, while FMDV and other major swine diseases were ruled out.

2.2. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Oral swab samples were placed in 3 mL of Minimum Essential Media (MEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) immediately after collection. At the laboratory the cotton swab was pressed against the tube wall to extract the liquid and the samples centrifuged at 3,000 rpm and the supernatant collected. To prepare a 10% (w/v) homogenate, vesicular epithelial samples were homogenized and mixed with 3 mL of MEM supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 1% antibiotics. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm, and the supernatant collected. The supernatants derived from swabs and tissue homogenates were subjected to automated nucleic acid extraction using the TANBead Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit (Taiwan Advanced Nanotech Inc., Taoyuan City, Taiwan). The nucleic acid extract was eluted with 100 μL elution buffer according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the LightCycler® 480 system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) in a 20 µL reaction mixture containing 4 µL of LightCycler® 480 Probes Master (2×; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 0.1 µL of AMV Reverse Transcriptase (10 U/µL; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), 1 µL each of forward and reverse primers (20 µM), 0.5 µL of probe (10 µM), 3 µL of RNA template, and 10.4 µL of DEPC-treated water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The thermal program was as follows: 50°C for 30 min (1 cycle), 95°C for 3 min (1 cycle), followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, and a final step at 40°C for 30 s. The synthesized cDNA was stored at −80°C until use.

2.3. Amplification of the SVA Genome and Sequencing

To amplify the SVA genome, we designed seven primer pairs based on the sequence of strain USA/KS15-031348/2015 (MN233025), as detailed in

Table 1. PCR conditions were optimized to amplify the complete genome with the Phusion Green Hot Start II High Fidelity DNA Polymerase kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

PCR products were purified from agarose gels followed by Sanger’s sequencing using the BigDye Terminator V3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the same primers as in the PCR. The sequencing reaction was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR reactions were performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 2700 Thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the following cycling parameters: 96°C initial denaturation for 1 min, followed by 45 cycles of 96°C denaturation for 10 sec, 50°C annealing for 10 sec, and 60°C elongation for 4 min. The sequencing products were analyzed using an ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Each nucleotide position was confirmed by sequencing at least two times.

2.4. Sequence Identity and Phylogenetic Analysis

The full length sequences and 4 structural proteins(VP1-4) of the 7 isolated SVA strains from this study were aligned with 18 reference sequences available in GenBank (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), as well as 12 additional sequences provided by the Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method in MEGA XI software (Pennsylvania State University, PA, USA) with a substitution model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates to determine the genetic relationships between the Taiwanese SVA strains and those from other countries.

2.5. Epitope Sequencec Analysis

In addition, amino acid sequence comparisons of known B cell epitopes were conducted by MEGA XI software. A total of nine previously identified linear B cell epitopes within VP1, VP2, and VP3 regions were analyzed based on published literature[

13,

14,

15]. The selected epitopes included

21GELAAP

26 within VP1;

12DRVITQT

18,

71WTKAVK

76,

98GGAFTA

103,

150KSLQELN

156,

177SLGTYYR

183,

248YKEGAT

253 and

266SPYFNGL

272 within VP2;

192GWFSLHKLTK

201 within VP3. Aligned amino acid sequences from seven Taiwanese isolates and 30 representative global SVA strains were analyzed to identify potential amino acid substitutions within these epitope regions.

2.6. Serological Surveillance

Serum samples were collected from commercial swine farms in Taiwan across 19 administrative divisions (counties/cities) of five regions: northern, central, southern, eastern, and the offshore islands regions. Three administrative divisions—Keelung City, Taipei City, and Lienchiang County—were excluded due to the absence of representative swine populations. The sample size was determined using the online Epitools sample size calculator (

https://epitools.ausvet.com.au/) assuming an expected herd level seroprevalence of 7.4% as reported in a 2022 study conducted on SVA seroprevalence in swine older than 20 weeks of age in the USA [

16], with a 5% precision and a 95% confidence interval. Based on a 2020 survey by the Ministry of Agriculture, Taiwan there were a total of 6,497 swine farms in Taiwan. Using this number as the population of farms at risk, at least 106 swine farms were required to be sampled, however a total of 300 farms were subsequently sampled to increase representativeness and reliability of the study. Serum samples were collected from at least 14 swine on each selected farm, a number calculated to be 95% confident of detecting at least three seropositive animals assuming a within-herd animal level seroprevalence of 20%. If there were fewer than 14 swine on the selected farm, all swine on that farm were sampled. The selected swine were monitored longitudinally, with two serum samples collected. The first sample set of samples was taken during the nursery stage (6-12 weeks), and the second set collected from the same pigs during the finisher stage (20-26 weeks) stages. This sampling design allowed for the detection of neutralizing antibody changes between the two stages. Serum samples were heat-inactivated at 56 °C for 30 minutes and stored at -20°C for subsequent analysis.

2.7. Anti-SVA Neutralizing Anitibody Assay

Antibodies to SVA were detected using the VNT assay. Serial two-fold dilutions of serum were carried out and mixed with 100 TCID

50 of the W107-0691 Taiwanese strain. After incubation at 37°C for 1 hour, then added the BHK-21 cells and inoculated at 37°C for 48 hours. Neutralizing titers were defined as the highest serum dilution that completely inhibited the cytopathic effect. Samples with neutralization antibody titters ≥1:64 were classified as positive[

17]. Farms were classified as seropositive for SVA if farm had over than two anti-SVA VNT-positive pigs of the same stage.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

To compare the herd level seroprevalence of SVA among different groups, pairwise comparisons were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10.4.1 (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA, USA ). Odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were also calculated to compare the seroprevalence between the regions. The OR calculations followed the methodology described in Statistical Methods in Epidemiology, Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Vol. 12, Oxford University Press, by Kahn HA and Sempos CT (1989). The SVA seroprevalence in administrative divisions was displayed using maps created with QGIS 3.28.7 (QGIS.org, an Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project headquartered in Beaverton, OR, USA).

4. Discussion

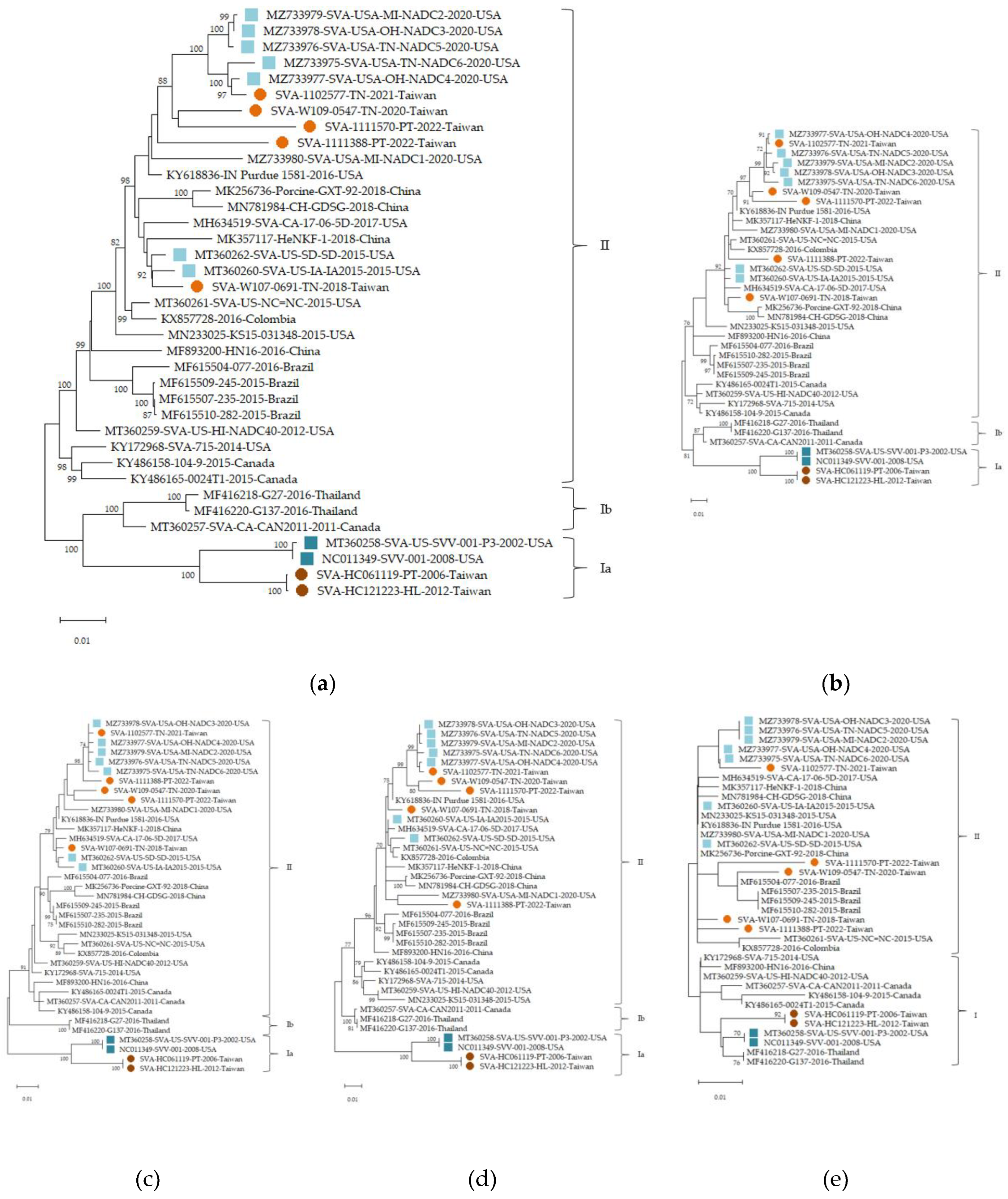

The phylogenetic analysis of SVA isolates from Taiwan revealed distinct clustering patterns corresponding to group Ia and II, consistent with studies by Joshi et al. (2020). HC061119 and HC121223, belonging to group Ia, showed high nucleotide identity (95.5% and 95.7%) with US-SVV-001-P3-2002, a strain with close phylogenetic relationship to the earliest characterized SVA viruses in the USA[

5]. This suggested that the Taiwanese historical strains may have originated from an early lineage of SVA. Furthermore, the five more recent Taiwanese strains (2018–2022) exhibited higher nucleotide (95.7–98.8%) and amino acid (97.2%–98.4%) sequence identity with SVA-USA-TN-NADC5-2020 (MZ733977), indicating the potential influence of international animal transport on viral evolution. Similar clustering of recent isolates within group II has been observed in other countries, emphasizing the global spread and diversification of SVA. A study by Buckley et al. (2021) further supported the evolutionary trends of SVA strains, reporting genetic differences between the SVV 001/2002 strain and other contemporary SVA strains. Their study revealed that SVV 001/2002 belonged to an independent evolutionary clade, while the other strains clustered within a separate clade[

18]. These findings aligned with our analysis of Taiwanese SVA strains, which also demonstrated genomic evolution of SVA. To further delineate the genetic relationships among SVA strains, we constructed phylogenetic trees based on the complete genome and the four structural protein-coding regions: VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1. The clustering patterns derived from nucleotide sequences analyses of VP1-VP3 were largely consistent with those from the full-length sequences phylogenetic tree, reinforcing the robustness of the observed phylogenetic groupings. Conversely, VP4 exhibited lower resolution with inconsistent clustering, likely due to the shorter sequence length and limited variability of the VP4 region. Therefore, VP4-based phylogenetic analysis should be interpreted with caution and regarded as supplementary to the more informative VP1–VP3-based results. These structural protein nucleotide sequence level comparisons provide additional evidence for the genetic divergence between the older Taiwanese strains (e.g., SVA-HC121223-HL-2012 in group Ia) and contemporary isolates, supporting the hypothesis of multiple introduction events or independent evolutionary events. Joshi et al. (2020) analyzed the full-length sequences of historical and contemporary SVA strains and reported a 6.32% genetic divergence between them. Their phylogenetic analysis revealed that most SVA strains cluster based on their geographic origins, suggesting independent evolution in different regions. However, some contemporary strains from PROC and Colombia clustered with strains isolated from the USA, indicating possible cross-regional transmission of SVA strains[

5]. Houston et al. (2020) provided a comprehensive review of the global distribution and evolutionary trends of SVA. They noted that historical SVA strains were primarily detected in North America, whereas contemporary SVA strains have spread globally, including the Americas and Asia. Furthermore, they highlighted the genetic divergence between historical and contemporary SVA strains, which aligns with the findings of Joshi et al. (2020). Previous reviews supported our observations on the global dissemination and genetic evolution of SVA, reinforcing the complexity of its evolutionary dynamics and transmission patterns[

3]. Furthermore, Saeng-chuto et al. (2018) reported that the SVA strains detected in Thailand were closely related to Canadian strains, suggesting that international swine transport is a contributing factor in the spread of SVA[

19]. The clustering of contemporary Taiwanese SVA isolates within group II highlights potential regional transmission patterns and viral evolution. Understanding these evolutionary dynamics is crucial for developing targeted control measures.

Moreover, analysis of linear B cell epitopes revealed high sequence conservation across Taiwanese and global strains, supporting their potential utility in broad-range diagnostic assays and immunogen design. Notably, most epitopes remained unchanged despite phylogenetic divergence, indicating antigenic stability. The few observed amino acid substitutions were rare and limited to individual strains, suggesting minimal impact on epitope-based recognition. These findings reinforce the suitability of conserved epitopes as reliable molecular targets. Interestingly, a substitution observed within the VP2 ¹²DRVITQT¹⁸ epitope was only observed in early North American isolates, including the first reported USA strain MT360258 (2002), NC011349 (2008), and one Canadian strain KY486158 (2015). This variation was absent in all other strains, including recent global and Taiwanese isolates. Such a pattern suggests that the T15I substitution may represent a variation from early SVA lineages rather than a feature of ongoing antigenic drift. Its disappearance in contemporary strains might reflect evolutionary constraints or selection pressure favoring the conserved DRVITQT motif. Similarly, a unique W71G substitution in the VP2 ⁷¹WTKAVK⁷⁶ epitope was observed in only one recent Taiwanese strain (1111570), with no comparable variation detected in other strains. The high conservation of this epitope in contemporary strains further supports its potential for serological assay development.

As an emerging vesicular disease pathogen in swine, SVA has spread across major swine-producing regions in the Americas and Asia [

8], with recent cases now reported in Europe. Notably, during a bilateral video conference on SVA research between VRI and the Pirbright Institute in the United Kingdom in 2024, it was highlighted that SVA cases have been detected in the UK, further emphasizing its expanding geographic distribution (UK Government News, 2024). Despite its growing geographic distribution in the swine industry, information on the animal and herd level prevalence of SVA is scant. One of the major challenges in studying the epidemiology of SVA is its tendency to result in subclinical infections, which may be unlikely to be detected without active surveillance or laboratory confirmation [

5,

16,

20]. Therefore, establishing baseline prevalence data is crucial for enhancing our understanding of the virus’s occurrence within pig populations and its national geographic distribution.

Our study revealed distinct differences in the seroprevalence of SVA between nursery and finisher swine, both at the herd and animal levels. The herd level seroprevalence for nursery swine was 53.0% (95% CI, 47.2–58.8), while for finisher swine, it was significantly lower at 6.7% (95% CI, 4.1–10.1, P<0.0001). Similarly, the animal level seroprevalence in nursery swine was 36.2% (95% CI, 34.8–37.7), which was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than the 4.6% (95% CI, 4.0–5.3) detected in finisher swine. However, herds were not significantly likely to seroconvert or become seronegative between the two sampling time points. Among the six herds classified as late seroconversion—those seronegative at the nursery stage but seropositive at the finisher stage—RRT-PCR testing was performed, and viral RNA was detected in three of them. This indicates that active or recent infection likely occurred between the two sampling points. The detection of SVA RNA in these herds provides additional support for the interpretation that late seroconversion reflects recent exposure post-weanings. It also underscores the dynamic nature of SVA transmission and highlights the value of integrating serological and molecular surveillance to capture the complete picture of virus circulation within herds.

The seropositive pigs in the nursery stage that turned seronegative in the finisher stage suggest possible shifts in immunity. Which are likely driven by maternal antibody transfer followed by subsequent viral exposure to the environment. These findings provide valuable insight into the immune status of pigs across different stages of growth and support the hypothesis that maternal immunity plays a key role in the immunity patterns observed in Taiwanese swine, as reported in other international studies ([

21,

22]). The observed reduction in seroprevalence with age in our study differs from the findings reported by Houston et al. (2019), where the herd level seroprevalence in nursery-finisher pigs (6–26 weeks) and sows (>26weeks) in the USA were 42.7% and 75.8%, respectively. Houston et al. noted in their discussion that while pigs around six weeks of age were included in their study, the presence of maternal antibodies in the youngest pigs could not be completely ruled out. This grouping approach and the potential influence of maternal immunity may have contributed to the higher overall seroprevalence reported in their study compared to our stratified analysis of different growth stages [

22]. In contrast, the seroprevalence of 7.4% in finisher pigs (20 weeks or older) reported by Preis et al. (2022) aligns closely with the low seroprevalence observed in finisher pigs in our study. Our study found a higher seroprevalence in nursery pigs compared to finisher pigs, which is consistent with Houston et al.'s findings of a higher prevalence in nursery-finisher pigs compared to the lower prevalence reported by Preis et al. in finisher pigs. Additionally, Preis et al. reported a herd level seroprevalence of 17.3% in breeding pigs, which was higher than that observed in finisher pigs[

23]. The stark contrast between the high sow seroprevalence reported by Houston et al. (2016) (75.8%) and the much lower rate observed by Preis et al. (2022) (17.3%) may indicate a declining trend in SVA circulation in the USA swine population over time. Notably, Houston’s study was conducted in 2016, shortly after the peak of SVA outbreaks in 2015, whereas Preis’s study was conducted during 2018–2019, when viral transmission may have diminished. This temporal difference underscores the importance of longitudinal surveillance in tracking the epidemiological dynamics of emerging vesicular diseases. In addition to temporal factors, methodological differences may also account for some of the variation in seroprevalence estimates. Preis et al. used immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for serological detection, while Houston et al. employed both ELISA and IFA with parallel interpretation, potentially increasing assay sensitivity. In contrast, our study used VNT, which, while more time and resource-intensive, is recommended by WOAH as the gold standard for antibody detection in other vesicular disease of swine caused by

Picornaviridae viruses, such as foot and mouth disease, due to its high specificity and reliability.

SVA transmission can occur through both direct contact with infected pigs and indirect contact with contaminated environments, transportation vehicles, or personnel. Breeding herds typically have higher stocking densities compared to nursery-finisher herds, which may facilitate more efficient viral transmission, further exacerbating the spread of SVA in these environments[

24]. Furthermore, sows could experience immune suppression during their reproductive cycles, which may increase their susceptibility to SVA infections. This immune suppression in sows could contribute to the higher SVA prevalence reported in these animals[

25], as the compromised immune response makes them more likely to virus shedding and subsequent transmission to their piglets. This, in conjunction with persistent viral shedding, may contribute to the higher seroprevalence in sows compared to nursery-finisher pigs [

25]. It was demonstrated that piglets born to SVA-infected sows acquire maternal antibodies, which can persist for up to 98 days post-birth[

21]. As sows are usually kept in commercial piggeries for several years they are more likely to be exposed to infection. The persistent nature of SVA infections complicates control efforts, as sows have been shown to shed the virus for up to 60 days post-infection. In contrast, when pigs are moved to nursery-finisher pens after weaning, they are housed in larger spaces with lower stocking density, reducing their potential exposure to the virus. Additionally, the faster turnover rate of nursery-finisher pigs—typically slaughtered around six months—further reduces their exposure time. Maternal immunity[

22] likely contributes to the higher seroprevalence observed in nursery swine compared to finishers, which aligns with the findings of this study.

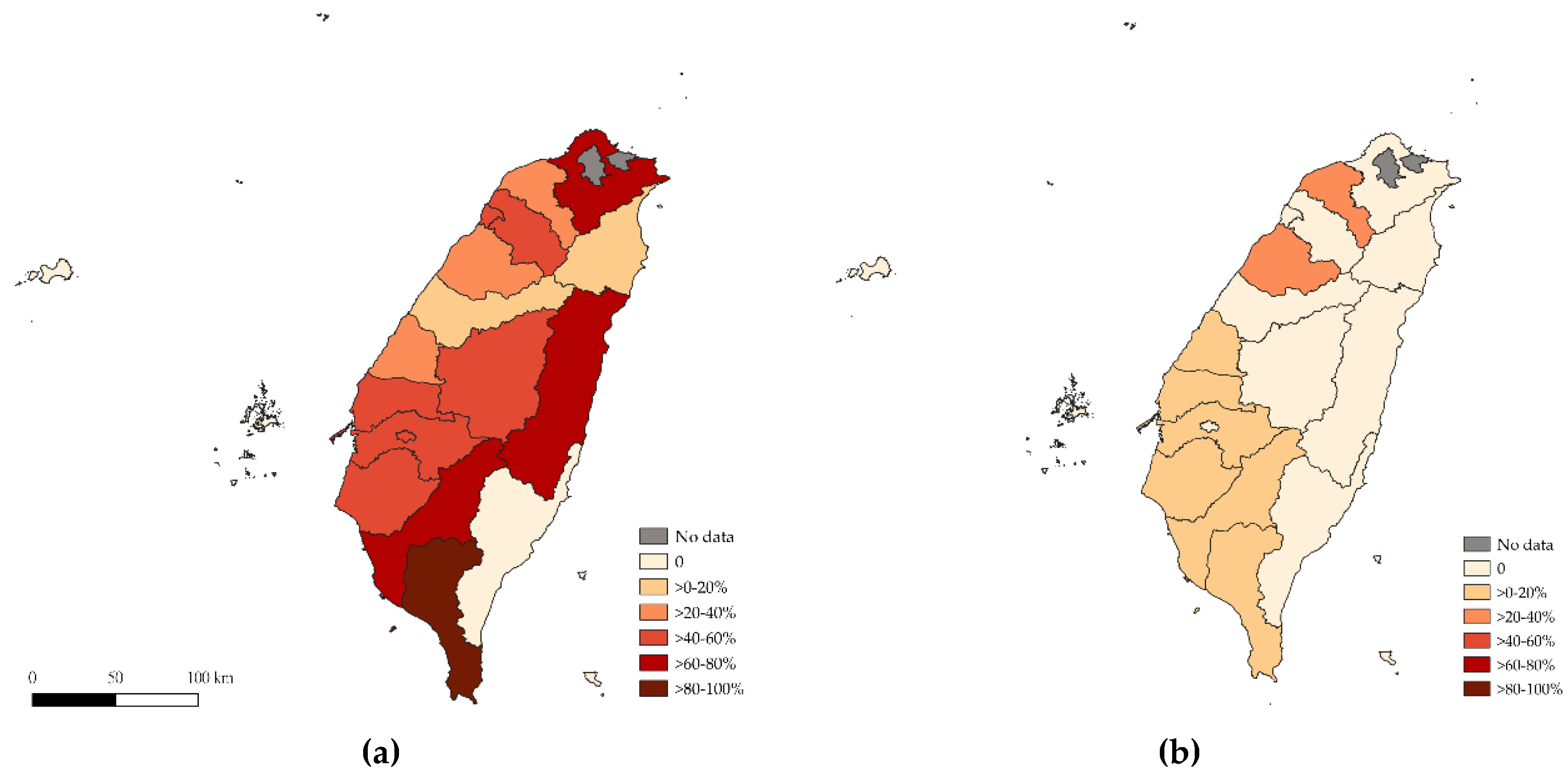

Our study also highlights significant regional variations in SVA seroprevalence. The herd level seroprevalence in nursery swine was significantly higher in the southern region compared to the northern region (OR 3.3; 95% CI, 1.4–7.7, P < 0.01). Also, the animal level seroprevalence in the central region was 1.5 times higher than that in the northern region (OR 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1–1.9, P = 0.0033), while the southern region exhibited even higher odds of seropositivity (OR 2.7; 95% CI, 2.2–3.5, P < 0.0001). For finisher swine, the highest herd level seroprevalence was observed in the central region, where the animal level seroprevalence was significantly higher than that of offshore islands (OR 8.5; 95% CI, 1.2–61.2, P = 0.0055). This regional difference may suggest that environmental or management factors, such as swine density, and farm-to-farm contacts, may play a role in SVA spread. Swine farming in Taiwan is primarily concentrated in the central and southern regions, which could contribute to the higher seroprevalence observed in these areas. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of regional differences and management factors in influencing the prevalence of swine diseases[

11,

16]. The close contact among pigs during mixing at markets or transportation significantly increases the risk of SVA transmission. Studies from North Carolina in USA have demonstrated that the circulation of SVA is prevalent in secondary markets (slaughterhouses that purchased lower quality pigs and cull sow markets[

8]). This highlighted that direct or indirect close contact between pigs, whether through mixing at markets or in densely stocked environments, facilitates the spread of the virus. Interestingly, no seropositive farms were detected from offshore islands in both the nursery and finisher stages. This might be a result of their geographical isolation.

Although SVA infection typically does not cause systemic disease, its vesicular lesions are clinically indistinguishable from those caused by high-consequence diseases such as FMD. The time and resources required for differential diagnosis are substantial, emphasizing the importance of studies like this in providing essential baseline data and informing the development of improved surveillance and diagnostic strategies.