Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, Viruses, Antibodies, and Animals

2.2. Clinical Sample Collection and Virus Detection

2.3. Viral Isolation and Identification

2.4. Plaque Assay and Plaque Size Determination

2.5. One-Step Growth Curve of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

2.6. Amplification and Sequencing of gB, gC, gD, and gE Genes of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

2.7. Complete Genome Sequencing of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

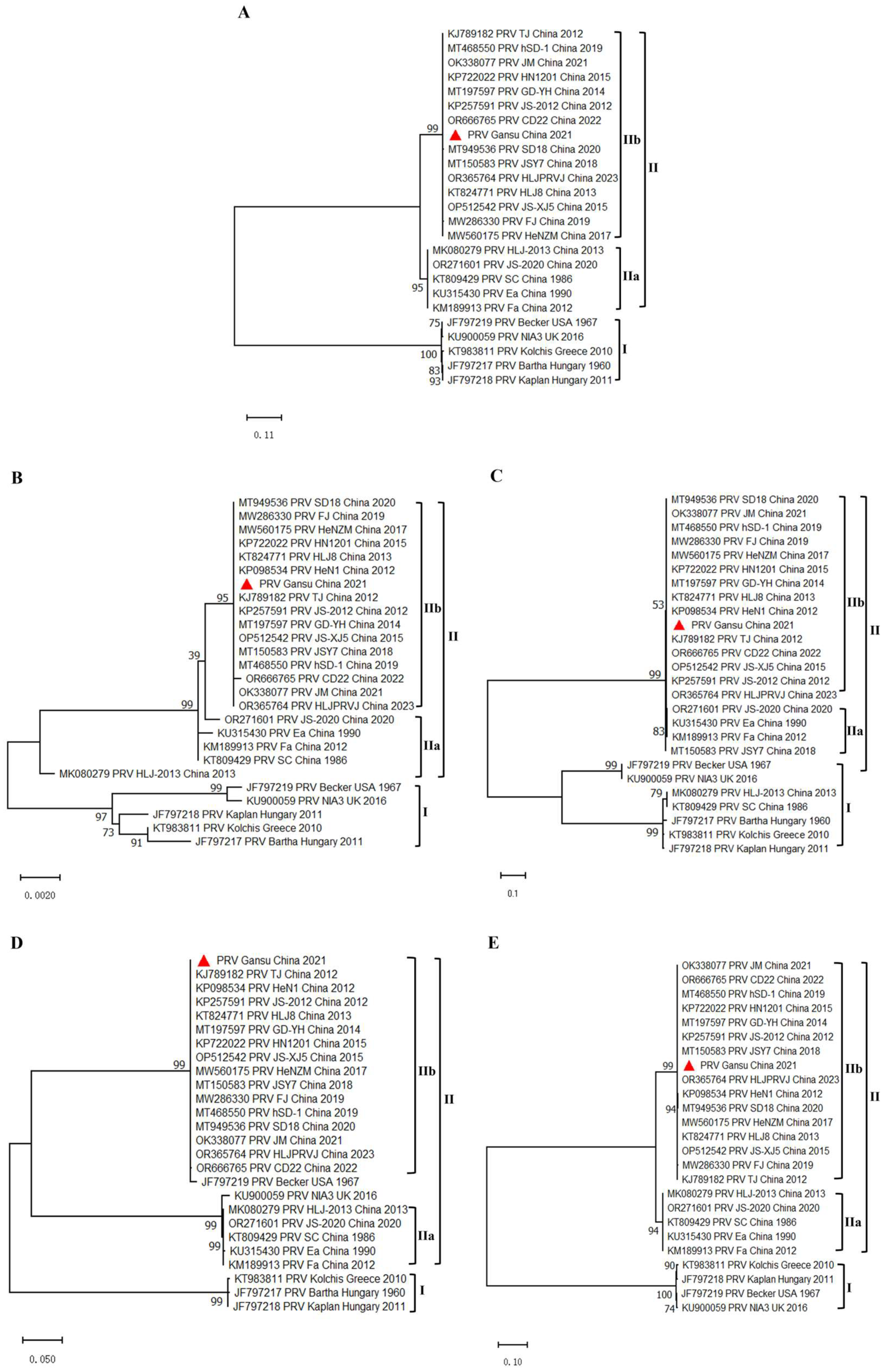

2.8. Phylogenetic Analyses of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

2.9. Challenge of Mice with the PRV GS-2021 Strain

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Detection of PRV in Clinical Brain Tissue using PCR

3.2. Isolation and Identification of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

3.3. Biological Characteristics of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

3.4. Genetic Features of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of the PRV GS-2021 Strain

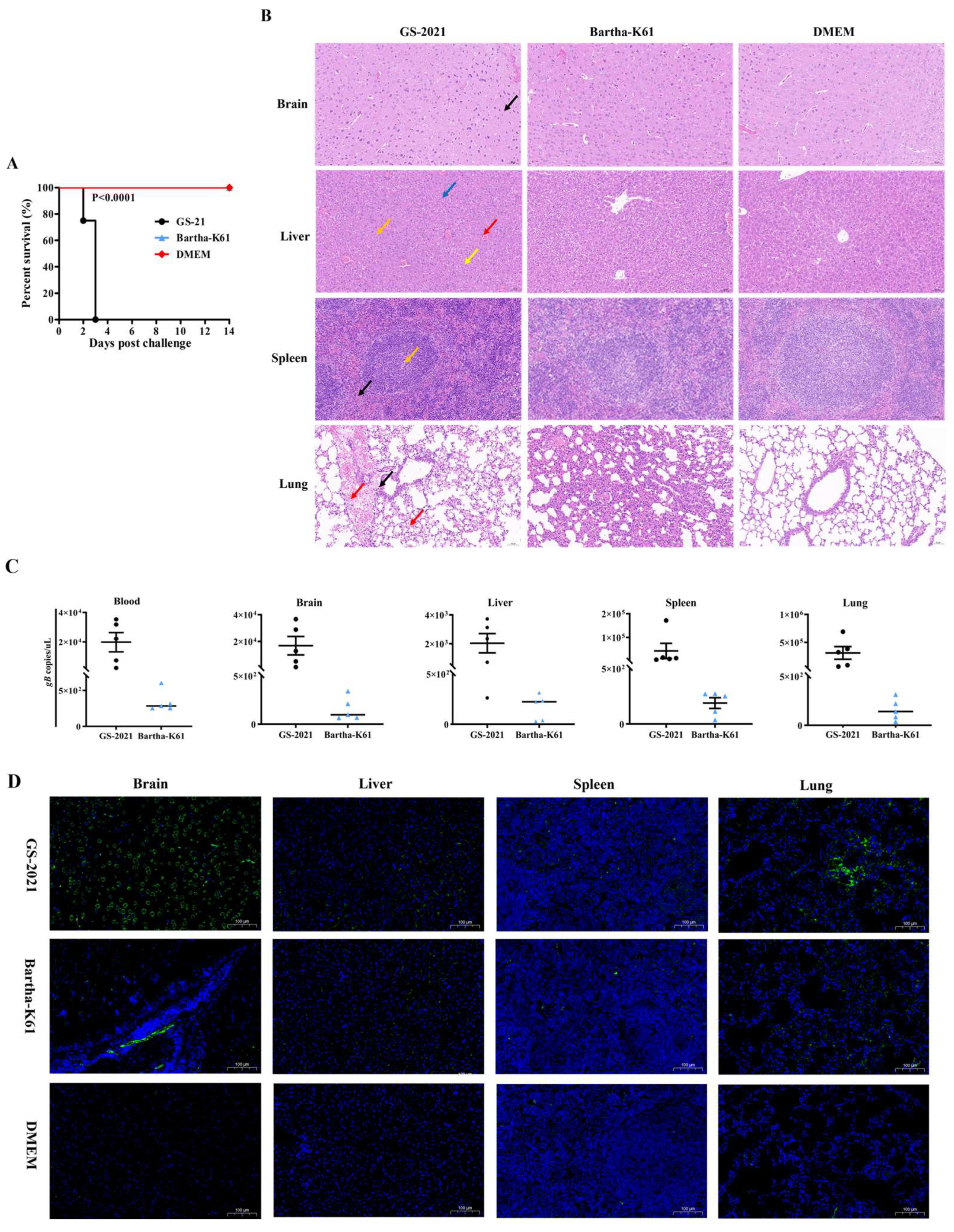

3.6. Pathogenicity of the PRV GS-2021 Strain in Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pomeranz, L.E.; Reynolds, A.E.; Hengartner, C.J. Molecular biology of pseudorabies virus: impact on neurovirology and veterinary medicine. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005, 69, 462–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.; Hahn, E.C.; Tottewitz, F.; Kramer, M.; Klupp, B.G.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Freuling, C. Pseudorabies virus in wild swine: A global perspective. Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 1691–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minamiguchi, K.; Kojima, S.; Sakumoto, K.; Kirisawa, R. Isolation and molecular characterization of a variant of Chinese gC-genotype II pseudorabies virus from a hunting dog infected by biting a wild boar in Japan and its pathogenicity in a mouse model. Virus Genes 2019, 55, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.J.; Xue, T.; Zhao, X.; Zou, J.; Pu, H.L.; Hu X.L., Tian, Z.G. Pseudorabies virus associations in wild animals: Review of potential reservoirs for cross-host transmission. Viruses 2022, 14, 2254.

- Duan, S.H.; Li, Z.M.; Yu, X.J.; Li, D. Alphaherpesvirus in pets and livestock. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laval, K.; Enquist, L.W. The neuropathic itch caused by Pseudorabies virus. Pathogens 2020, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Guo, W.Z.; Xu, Z.W. Fluctuant rule of colostral antibodies and the date of initial immunization for the piglets from sows inoculated with pseudorabies virus gene-deleted vaccine SA215. Chin. J. Vet. Med. 2004, 24, 320–322. (In Chinese).

- He, Q.G.; Chen, H.C.; Fang, L.R.; Wu, B.; Liu, Z.F.; Xiao, S.B.; Jin, M.L. The safety, stability and immunogenicity of double genenegative mutant of pseudorabies virus strain (PRV HB-98). Chin. J. Vet. Med. 2006, 26, 165–168. (In Chinese).

- Chen, Q.Y.; Wu, X.M.; Che, Y.L.; Chen, R.J.; Hou, B.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, L.B.; Zhou, L.J. The immune efficacy of inactivated Pseudorabies vaccine prepared from FJ-2012∆gE/gI strain. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, Y.; Wang, C.H.; Yuan, J.; Li, N.; Song, K.; Qiu, H.J. Control of swine pseudorabies in China: Opportunities and limitations. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 183, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freuling, C.M.; Müller, T.F.; Mettenleiter, T.C. Vaccines against pseudorabies virus (PrV). Vet Microbiol. 2017, 206, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.L.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, D.M.; Zhang, Q.; Han, T.; Li, X.; Gu, X.X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.Y.; Qu, P.; Liu, J.H.; Zhao, X.Y.; Tian, K.G. Pathogenic pseudorabies virus, China, 2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.Q.; Peng, J.M.; Tian, Z.J.; Zhao, H.Y.; Li, N.; Liu, Y.M.; Chen, J.Z.; Leng, C.L.; Sun, Y.; Chang, D.; Tong, G.Z. Pseudorabies virus variant in Bartha-K61-vaccinated pigs, China, 2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.M.; Chen, Q.Y.; Chen, R.J.; Che, Y.L.; Wang, L.B.; Wang, C.Y.; Yan, S.; Liu, Y.T.; Xiu, J.S.; Zhou, L.J. Pathogenicity and whole genome sequence analysis of a Pseudorabies virus strain FJ-2012 isolated from Fujian, Southern China. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med Microbiol. 2017, 2017, 9073172. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.Z.; Li, N.; Cong, X.; Wang, C.H.; Du, M.; Li. L.; Zhao, B.B.; Yuan, J.; Liu, D.D.; Li, S.; Li Y.F.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, H.J. Pathogenicity and genomic characterization of a pseudorabies virus variant isolated from Bartha-K61-vaccinated swine population in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2014, 174, 107–115.

- Gu, Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, J.; Hou, C.; Sun, H.; Yang, W.; Bai, J.; Jiang, P. A novel inactivated gE/gI deleted pseudorabies virus (PRV) vaccine completely protects pigs from an emerged variant PRV challenge. Virus Res. 2015, 195, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Li, G.; Liang, C.; Liu, F.; Tian, Q.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, H.; Tong, G. A live, attenuated pseudorabies virus strain JS-2012 deleted for gE/gI protects against both classical and emerging strains. Antivir. Res. 2016, 130, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, R.M.; Zhou, Q.; Song, W.B.; Sun, E.C.; Zhang, M.M.; He, Q.G.; Chen, H.C.; Wu, B.; Liu, Z.-F. Novel pseudorabies virus variant with defects in TK, gE and gI protects growing pigs against lethal challenge. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5733–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.T.; Auclert, L.Z.; Zhai, X.F.; Wong, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.N.; Xing, G.; Wang, S.L.; He, W.; Li, K.M.; Wang, L.; Han, G.Z.; Veit, M.; Zhou, J.Y. Suo, G. Interspecies transmission, genetic diversity, and evolutionary dynamics of pseudorabies virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 1705–1715.

- Bo, Z.Y.; Li, X.D. A Review of pseudorabies virus variants: genomics, vaccination, transmission, and zoonotic potential. Viruses 2022, 14, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Kuang, Y.; Li, Y.F.; Guo, H.H.; Zhou, C.Y.; Guo, S.B.; Tan, C.; Wu, B.; Chen, H.C.; Wang, X.R. The epidemiology and variation in pseudorabies virus: a continuing challenge to pigs and humans. Viruses 2022, 14, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yao, J.; Yang, Y.D.; Luo, W.; Yuan, X.M.; Yang, L.C.; Wang, A.B. Current status and challenge of pseudorabies virus infection in China. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 588–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.Y.; Sun, Z.; Tan, F.F.; Guo, L.H.; Wang, Y.Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L.L.; Li, X.D.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, K.G. Pathogenicity of a currently circulating Chinese variant pseudorabies virus in pigs. World J. Virol. 2016, 5, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, S.L.; Lei, J.L.; Cong, X.; Xiang, G.T.; Luo, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, H.J. Dose-dependent pathogenicity of a pseudorabies virus variant in pigs inoculated via intranasal route. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 168, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.Z.; Li, S.; Wang, X.B.; Zou, M.M.; Gao, S. Bartha-k61 vaccine protects growing pigs against challenge with an emerging variant pseudorabies virus. Vaccine 2017, 35, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, X.B.; Wang, W.B.; Gao, S.; Liu, X.F.; Kai, Y.; Chen, C.H. Efficacy of the Bartha-K61 vaccine and a gE-/gI-/TK- prototype vaccine against variant porcine pseudorabies virus (vPRV) in piglets with sublethal challenge of vPRV. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.H.; Li, L.; Pan, H.C.; Wang, X.B.; Gao, Q.Q.; Huan, C.C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, L.Y.; Gao, S.; Kai, Y.; Chen, C.H. Same dosages of rPRV/XJ5-gI-/gE-/TK- prototype vaccine or Bartha-K61 vaccine similarly protects growing pigs against lethal challenge of emerging vPRV/XJ-5 strain. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 896689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, K.V.; Michailidou, M.; Grivas, I.; Petridou, E.; Stamelou, E.; Efraimidis, K.; Chen, L.; Drew, T.W.; Kritas, S.K. Bartha-K61 vaccine protects nursery pigs against challenge with novel European and Asian strains of Suid herpesvirus 1. Vet. Res. 2022, 53, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yan, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Yan, H.; Gao, Z.Y.; Wang. L.L.; Li, X.D.; Tan, F.F.; Tian, K.G. Construction of a gE-deleted Pseudorabies virus and its efficacy to the new-emerging variant PRV challenge in the form of killed vaccine. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 684945.

- Zhang, C.; Guo, L.; Jia, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Tan, F.; Tian, K. Construction of a triple gene-deleted Chinese Pseudorabies virus variant and its efficacy study as a vaccine candidate on suckling piglets. Vaccine 2015, 33, 2432–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.F.; Lai, Z.; Shu, Y.H.; Qi, S.H.; Ma, J.J.; Wu, B.Q.; Gong, J.P. Isolation and identification of porcine pseudorabies virus (PRV) C strain. Acta Agric. Shanghai 2015, 31, 32–36. (In Chinese).

- Tang, Y.D.; Liu, J.T.; Wang, T.Y.; An, T.Q.; Sun, M.X.; Wang, S.J.; Fang, Q.Q.; Hou, L.L.; Tian, Z.J.; Cai, X.H. Live attenuated pseudorabies virus developed using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Virus Res. 2016, 225, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Z.Y.; Miao, Y.Y.; Xi, R.; Gao, X.Y.; Miao, D.L.; Chen, H.; Jung, Y.Se.; Qian, Y.J.; Dai, J.J. Emergence of a novel pathogenic recombinant virus from Bartha vaccine and variant pseudorabies virus in China. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan L, Yao J, Lei L, Xu K, Liao F, Yang S, Yang L, Shu X, Duan D, Wang A. Emergence of a novel recombinant Pseudorabies virus derived from the field virus and its attenuated vaccine in China. Front Vet Sci. 2022, 9, 872002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Qin, S.; Huang, X.; Xu, L.; Ouyang, K.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Z.; Huang, W. Isolation and identification of two novel pseudorabies viruses with natural recombination or TK gene deletion in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2023, 280, 109703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian Z, Liu P, Zhu Z, Sun Z, Yu X, Deng J, Li R, Li X, Tian K. Isolation and characterization of a novel recombinant classical Pseudorabies virus in the context of the variant strains pandemic in China. Viruses. 2023, 15, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Zhu L, Zhao J, Yin X, Feng Y, Wang X, Sun X, Zhou Y, Xu Z. Genetic evolution analysis of novel recombinant pseudorabies virus strain in Sichuan, China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020, 67, 1428-1432.

- Huang J, Tang W, Wang X, Zhao J, Peng K, Sun X, Li S, Kuang S, Zhu L, Zhou Y, Xu Z. The Genetic Characterization of a novel natural recombinant Pseudorabies virus in China. Viruses. 2022, 14, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Cheng J, Pan H, Yang F, Zhu X, Wu J, Pan H, Yan P, Zhou J, Gao Q, Huan C, Gao S. Analysis of the recombination and evolution of the new type mutant pseudorabies virus XJ5 in China. BMC Genomics. 2024, 25, 752. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.D.; Wei, Q.T.; Wu, C.Y.; Ye, Z.Q.; Qin, L.T.; Chen, T.; Sun, Z.; Tian, K.G.; Li, X.D. Isolation and pathogenicity of a novel recombinant pseudorabies virus from the attenuated vaccine and classical strains. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1579148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; Zhou, Y.J.; Qiu, Y.X.; Lei, L.; Wang, C.; Zhu, P.; Duan, D.Y.; Lei, H.Y.; Yang, L.C.; Wang, N.D.; Yang, Y.; Yao, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, A.B. Pseudorabies in pig industry of China: Epidemiology in pigs and practitioner awareness. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 973450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.W.; Weng, S.S.; Cheng, Q.; Cui, P.; Li, Y.J.; Wu, H.L.; Zhu, Y.M.; Xu, B.; Zhang, W.H. Human endophthalmitis caused by pseudorabies virus infection, China, 2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1087–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Guan, H.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.J.; Zhao, X.H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.M. Characteristics of human encephalitis caused by pseudorabies virus: A case series study. Int J Infect Dis. 2019, 87, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tao, X.G.; Fei, M.M.; Chen, J.; Guo, W.; Li, P.; Wang, J.Q. Human encephalitis caused by pseudorabies virus infection: a case report. J Neurovirol. 2020, 26, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Lu, J.H.; Zhang, W.H.; Gao, G.F. Pseudorabies virus: a neglected zoonotic pathogen in humans? Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Chen, X.X.; Zhang, G.P. Human PRV infection in China: an alarm to accelerate eradication of PRV in domestic pigs. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.D.; Zhao, Y.; Yi, A.F. Human encephalitis caused by Pseudorabies virus in China: A case report and systematic review. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2022, 22, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.Q.; Hu, Z. P.; Zhang, Y. C.; Wu, X.M.; Zhang, H.N. Case report: Metagenomic next-generation sequencing for diagnosis of human encephalitis and endophthalmitis caused by Pseudorabies virus. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 8, 753988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Gao, J.; Hua, R.Q.; Zhang, G.P. Pseudorabies virus as a zoonosis: scientific and public health implications. Virus Genes 2025, 61, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Wang, X.J.; Xie, C.H.; Ding, S.F.; Yang, H.N.; Guo, S.B.; Li, J.X.; Qin, L.Z.; Ban, F.G.; Wang, D.F.; Wang, C.; Feng, L.X.; Ma, H.C.; Wu, B.; Zhang, L.P.; Dong, C.X.; Xing, L.; Zhang, J.W.; Chen, H.C.; Yan, R.Q.; Wang, X.R.; Li, W. A novel human acute encephalitis caused by pseudorabies virus variant strain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e3690–e3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Liu, Q.Y.; Zhang, Y.B.; Wu, B.; Chen, H.C.; Wang, X.R. Cytopathic and genomic characteristics of a human-originated pseudorabies virus. Viruses 2023, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.H.; Fu, P.F.; Chen, H.Y.; Wang, Z.Y. Pseudorabies virus: From pathogenesis to prevention strategies. Viruses 2022, 14, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehl, J.; Teifke, J.P. Comparative pathology of pseudorabies in different naturally and experimentally infected species-A review. Pathogens 2020, 9, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.J.; Cheng, N.; Yang, C.; Li, X.L.; Sun, J.Y.; Sun, Y.F. Emergence and etiological characteristics of novel genotype pseudorabies virus variant with high pathogenicity in Tianjin, China. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 197, 107061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.L.; Gong, J.S.; Shen, J.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.B.; Liu, Q.X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Q.P. Advances in molecular epidemiology and detection methods of pseudorabies virus. Discov. Nano. 2025, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.F.; Zhao, W.; Li, K.M.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.C.; Su, S.; Zhou, J.Y.; Lei, J.; Xing, G.; Sun, H.F.; Shi, Z.Y.; Gu, J.Y. Genome characteristics and evolution of pseudorabies virus strains in eastern China from 2017 to 2019. Virol. Sin. 2019, 34, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Li, S.E.; He, W.; Liu Z.J.; Zhou, X.N.; Ma, Z.X.; Sun, Y.P. Investigation and prevention of Pseudorabies in pig farms in Qingyang, Gansu. Gansu Anim Husbandry and Vet Med. 2011, 41, 5–6. (In Chinese).

- Kang, W.B.; Song, J.G.; Zhou, F.; Xue, X.J.; Zhang, L.; Kang, X.H. Serological investigation and suggestions of prevention and control of pseudorabies in large-scale pig farms in Gansu Province. Anim. Sci. Abroad 2015, 35, 50–52. (In Chinese).

- Wang, M.J.; Wang, J.Q.; Cheng, X.L.; Wang, Y. Sero-epidemiological investigation on Pseudorabies in scaled swine farms in Tianshui city of Gansu Province. China Anim Health Inspection 2023, 40, 15–18. (In Chinese).

- Tang, Y.D.; Liu, J.T.; Wang, T.Y.; Sun, M.X.; Tian, Z.J.; Cai, X.H. Comparison of pathogenicity-related genes in the current pseudorabies virus outbreak in China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, C.; Wei, Q.; Ye, Z.; Wang, W.; Sun, Z.; Tian, K.; Li, X. Emergence and characterization of three Pseudorabies variants with moderate pathogenicity in growing pigs. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.L.; Kong, Z.J.; Liu, P.; Fu, Z.D.; Zhang, J.D.; Liu, M.D.; Shang, L.Y. Natural infection of a variant pseudorabies virus leads to bovine death in China. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.Q. ; Liu, Ning. ; Tan, L.; Gao, L.; Zhu G.Y.; Tao, Z.Z.; Liu, B.Y.; Wang, A.B.; Yao, J. Isolation and biological characterization of a variant pseudorabies virus strain from goats in Yunnan Province, China. Vet Res Commun. 2025, 49, 149. [Google Scholar]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5' - 3') | Length |

|---|---|---|

| gB gC gD gE gB gE gB |

TGTACCTGACCTACGAGGCGTCATG GTGGGAGCCGTCACACGCGCCAGC TGTGTGCCACTAGCATTAAATCCGTT GTTCAACGCGCGGTCGTTTATTGAT ATACACTCACCTGCCAGCGCCATG ACCATCATCATCGACGCCGGTACT GTTGAGACCATGCGGCCCTTTCT GGACCGGTTCTCCCGGTATTTAAG TGCCCACGCACGAGGACTACTACG CGCCATAGTTGGGTCCATTCGTCAC TGCAGAACAAGGACCGCACCCTGT GCGAGATGAGGAGCTCGTTGTCGT AAGTTCAAGGCCCACATCT TGAAGCGGTTCGTGATGG FAM-CAAGAACGTCATCGTCACGACCG-BHQ |

2818 bp 1605 bp 1262 bp 1786 bp 258 bp 282 bp 88 bp |

| Strain | Accession Number | Genotype | Country | Isolation Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TJ | KJ789182 | IIb | China | 2012 |

| HeN1 | KP098534 | IIb | China | 2012 |

| JS-2012 | KP257591 | IIb | China | 2012 |

| HLJ8 | KT824771 | IIb | China | 2013 |

| GD-YH | MT197597 | IIb | China | 2014 |

| HN1201 | KP722022 | IIb | China | 2015 |

| JS-XJ5 | OP512542 | IIb | China | 2016 |

| HeNZM | MT775883 | IIb | China | 2017 |

| JSY7 | MT150583 | IIb | China | 2018 |

| FJ | MW286330 | IIb | China | 2019 |

| hSD-1 | MT468550 | IIb | China | 2019 |

| SD18 | MT949536 | IIb | China | 2020 |

| JM | OK338077 | IIb | China | 2021 |

| CD22 | OR666765 | IIb | China | 2022 |

| HLJPRVJ | OR365764 | IIb | China | 2023 |

| HLJ-2013 | MK080279 | IIa | China | 2013 |

| JS-2020 | OR271601 | IIa | China | 2020 |

| SC | KT809429 | IIa | China | 1986 |

| Ea | KU315430 | IIa | China | 1990 |

| Fa | KM189913 | IIa | China | 2012 |

| Kolchis | KT983811 | I | Greece | 2010 |

| Bartha | JF797217 | I | Hungary | 1960 |

| Kaplan | JF797218 | I | Hungary | 2011 |

| Becker | JF797219 | I | USA | 1967 |

| NIA3 | KU900059 | I | UK | 2016 |

| Strain | Accession Number |

Genome Sequence | T (%) | C (%) | A (%) | G (%) | G+C (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TJ | 143642 | 143642 | 13.27 | 36.94 | 13.10 | 36.69 | 73.63 |

| HeN1 | 141803 | 141803 | 13.26 | 36.96 | 13.05 | 36.73 | 73.69 |

| JS-2012 | 145312 | 145312 | 13.29 | 36.78 | 13.21 | 36.73 | 73.50 |

| HLJ8 | 142298 | 142298 | 13.22 | 36.91 | 13.08 | 36.79 | 73.70 |

| GD-YH | 146012 | 146012 | 13.17 | 36.83 | 13.07 | 36.93 | 73.76 |

| HN1201 | 144173 | 144173 | 13.27 | 36.81 | 13.18 | 36.73 | 73.54 |

| JS-XJ5 | 141955 | 141955 | 13.22 | 37.05 | 12.99 | 36.75 | 73.79 |

| HeNZM | 144235 | 144235 | 13.33 | 36.61 | 13.09 | 36.98 | 73.58 |

| JSY7 | 144315 | 143452 | 13.17 | 36.98 | 13.01 | 3684 | 73.82 |

| FJ | 142763 | 142763 | 13.19 | 36.86 | 13.43 | 36.52 | 73.38 |

| hSD-1 | 143236 | 143236 | 13.25 | 36.88 | 13.12 | 36.75 | 73.63 |

| SD18 | 143905 | 143905 | 13.24 | 36.87 | 13.10 | 36.79 | 73.66 |

| JM | 144046 | 144046 | 13.19 | 36.92 | 13.06 | 36.83 | 73.75 |

| CD22 | 142472 | 142472 | 13.23 | 37.05 | 13.03 | 36.69 | 73.74 |

| HLJPRVJ | 143520 | 143520 | 13.29 | 36.93 | 13.10 | 36.69 | 73.61 |

| HLJ-2013 | 142560 | 142560 | 13.23 | 36.95 | 13.09 | 36.73 | 73.67 |

| JS-2020 | 143246 | 143246 | 13.27 | 36.88 | 13.10 | 36.74 | 73.62 |

| SC | 142825 | 142825 | 13.26 | 36.93 | 13.13 | 36.68 | 73.61 |

| Ea | 142334 | 142334 | 13.28 | 36.89 | 13.12 | 36.72 | 73.60 |

| Fa | 141930 | 141930 | 13.25 | 36.89 | 13.06 | 36.80 | 73.70 |

| Kolchis | 141542 | 141542 | 13.23 | 37.11 | 13.08 | 36.58 | 73.69 |

| Bartha | 137764 | 137764 | 13.19 | 36.98 | 13.10 | 36.73 | 73.71 |

| Kaplan | 140377 | 140377 | 13.22 | 37.05 | 13.10 | 36.63 | 73.68 |

| Becker | 141113 | 141113 | 13.15 | 37.00 | 13.11 | 36.74 | 73.74 |

| NIA3 | 142228 | 142228 | 13.15 | 36.97 | 13.11 | 36.77 | 73.74 |

| Comparison with the PRV GS-2021 Strain |

Nucleotide Identities (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Sequence | gB | gC | gD | gE | |

| Chinese PRV variant strains | 99.59-99.96 | 99.90-100.00 | 99.90-100.00 | 99.80-100.00 | 99.70-99.90 |

| Chinese classical PRV strains | 98.40-99.48 | 99.30-99.80 | 96.90-99.70 | 99.50-99.70 | 99.70 |

| Foreign classical PRV strains | 96.02-97.31 | 98.40-98.50 | 94.90-96.30 | 98.90-99.30 | 97.70-98.0 |

| Group | Mice number in each group |

Dose (PFU) | Mortality | LD50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS-2021 | 8 | 104 | 8/8 | 102.125/0.01ul |

| 8 | 103 | 8/8 | ||

| 8 | 102 | 3/8 | ||

| Bartha-K61 | 8 | 106 | 5/8 | 105.75/0.01ul |

| 8 | 105 | 1/8 | ||

| 8 | 104 | 0/8 | ||

| DMEM | 8 | / | 0/8 | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).