1. Introduction

Porcine circoviruses are among the most significant viral agents affecting global swine health. They have implications for animal welfare, productivity, and economic sustainability.

The

Circoviridae family contains multiple viruses that can infect swine, including domestic pigs and wild boars. Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) is the most studied virus in this family due to its association with porcine circovirus-associated diseases (PCVAD). PCVAD is a complex of syndromes that causes severe illness and reproductive disorders in swine. In 2016, a new member of the

Circoviridae family emerged: porcine circovirus type 3 (PCV3). It was first reported in the United States and later in several other locations, including Asia and European countries such as Italy [

2], Spain [

3], Poland [

4] and Portugal [

5]

While the pathogenic potential of PCV3 remains under investigation, it has been detected in both symptomatic and asymptomatic animals, suggesting that it may play a role in subclinical infections or act as a cofactor in disease development. PCV2 has been effectively controlled in many commercial pig populations through widespread vaccination, leading to a significant reduction in clinical disease and viral prevalence [

7,

8]. However, there is currently no available vaccine for PCV3, and its epidemiological dynamics are still understudied. This knowledge gap raises concerns about PCV3 circulation, particularly in regions where it coexists with PCV2.

The role of wild boars (

Sus scrofa) as reservoirs for swine pathogens is receiving increased attention. Their growing populations and potential to interact with domestic herds, either directly or through shared environments, pose challenges to biosecurity and disease control [

9].

Recent studies by our research group have shown that PCV2 remains in circulation in the swine population despite control measures implemented in Portugal through vaccination programs since 2007 [

5,

8].

The goal of this study is to evaluate the prevalence of PCV2 and PCV3 in domestic pigs and wild boars in mainland Portugal, as well as to compare the viral loads in both groups, using Cycle threshold (Ct) values. By examining both populations and including multiple tissue types and production stages, this research contributes to a better understanding of virus circulation, the impact of vaccination, and potential interactions between PCV2 and PCV3.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample collection and nucleic acids extraction

From August to December 2024, feces from 160 domestic pigs were collected from domestic pig farms in seven districts of mainland Portugal (Santarém, Lisbon, Leiria, Setúbal, Aveiro, Faro, and Coimbra). Additionally, 120 organ samples from various tissues were collected from wild boars in seven districts (Santarém, Évora, Beja, Aveiro, Guarda, Castelo Branco, and Portalegre) from October 2023 to February 2025. The selection of different districts for sampling domestic pigs and wild boars, with only two overlapping, enabled full coverage of the southern and central regions of mainland Portugal.

Sample preparation involved diluting a small amount of feces to 20% (w/v) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The suspension was vortexed to ensure thorough homogenization, then centrifuged at 2,000× g for 10 minutes to remove debris. The organ samples were homogenized at 20% (w/v) in PBS in a Precellys tissue homogenizer (Bertin Technologies, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) with zirconium spheres, and clarified at 2,000 ×g for 5 minutes. Nucleic acids were extracted using the IndiMag Pathogen Kit (Indical) on the KingFisher Flex nucleic acid extraction system (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.2. qPCR for PCV2 and PCV3 detection

For both PCV2 and PCV3, the reaction mix included 1 µM of forward primer, 1 µM of reverse primer, 0.2 µM of probe, and 12.5 µL of buffer (SPEEDY NZYTaq 2x Colourless Master Mix from NZYTech, Portugal). For PCV2, 5 µL of DNA was used, while for PCV3, only 2.5 µL of sample was used. The total volume was adjusted to 25 µL with nuclease-free water. Primer sequences are listed in

Table 1.

The qPCR amplification program performed to detect PCV2 viral rep gene consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 2 seconds, annealing at 52°C for 5 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 5 seconds. For the PCV3 qPCR, targeting the cap gene, the amplification program included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 2 seconds and an annealing/extension step at 60°C for 5 seconds.

The viral load was inferred from the cycle threshold (Ct) values, with lower Ct values indicating higher amounts of viral DNA present in the sample, as fewer amplification cycles are needed to reach the detection threshold.

2.3. Conventional PCR amplification of positive qPCR samples

Four PCV2-positive samples (3 from pigs and 1 from a wild boar) and 1 PCV3-positive sample from a wild boar were selected for Sanger sequencing based on their collection sites, in order to infer genetic differences between different districts in mainland Portugal

PCV2 reaction mix included 1 µM primer S4, 1 µM primer AS4 (

Table 1), 12.5 µL of NZYTaq II 2x Green Master Mix (NZYTech, Portugal), 5 µL DNA and water to a total volume of 25 µL. The amplification program started with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 58°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 90 seconds, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. The amplified fragment has an expected size of 494 bp.

PCV3 reaction mix included 1 µM primer PCV3_seq2_FW, 1 µM primer PCV3_seq2_RV (

Table 1), 12.5 µL NZYTaq II 2x Green Master Mix (NZYTech, Portugal), 2.5 µL DNA and water to a total volume of 25 µL. The amplification program started with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 56°C for 30 seconds and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, and a final extension step at 72°C for 5 minutes. The amplified fragment has an expected size of 825 bp.

The amplification products were observed in a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis with GreenSafe (NZYTech, Portugal) in GelDoc Go Imaging System (BioRad, USA) and the specific products were excised and purified using the NZYGelpure kit (NZYTech, Portugal). Primer sequences are listed in

Table 1.

2.4. Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing was carried out using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The forward and reverse primers from the amplification step were used. Each reaction (10 µl total volume) included 1 µl of sequencing buffer, 2 µl of sequencing mix, 2.5 µM primer, and an appropriate volume of DNA, adjusted based on fragment concentration. The sequencing protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 96°C for 1 minute, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 96°C for 10 seconds, annealing at 58°C for PCV2 or 56°C for PCV3 for 5 seconds, and extension at 60°C for 1 minute. The products were purified using sodium acetate (3M, pH 5.2), 125 mM EDTA, and 100% ethanol. After drying, samples were resuspended in formamide and sequenced using a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence reads were assembled with SeqScape v2.5 software (Applied Biosystems).

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis

To identify the genotypes of PCV2 and PCV3 strains circulating in domestic pigs and wild boars in Portugal, the sequences obtained were aligned with representative GenBank sequences originated from different hosts, regions, and years. Multiple sequence alignments were performed using AliView program (version 1.28). The best-fit substitution models were selected in MEGA X (v10.0.5) based on model selection criteria. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum likelihood method: the TIM2+F+I+G4 (Transitional model 2) model was applied for PCV2 and the TN+F+I+G4 (Tamura-Nei) model for PCV3. Initial trees for heuristic searches were generated using the Neighbor-Joining algorithm with distances estimated via the Maximum Composite Likelihood method. Site-specific rate heterogeneity was modeled using a discrete Gamma distribution with invariant sites allowed.

3. Results

Samples from domestic pigs were categorized into six production stages: Quarantine (n = 5), Nursery (n = 24), Fattening (n = 28), Breeding Stalls (n = 21), Gestation (n = 44), and Maternity (n = 38). All 160 samples were collected from feces. In contrast, the 120 samples from wild boars were collected from various tissues, including the liver, spleen, bone marrow, lungs, retropharyngeal lymph nodes, submandibular lymph nodes, and diaphragm. The presence of PCV2 and PCV3 viruses was detected in all types of analyzed tissues (

Table 2).

Of the 280 swine tested, 33.93% (n = 95) were infected with PCV2 and 30.00% (n = 84 were infected) with PCV3. Coinfection was detected in 1 domestic pig and in 52 wild boars. While 87.50% (n = 140) of domestic pigs tested negative for both viruses, 3 pigs positive for PCV2, 18 for PCV3, and 1 coinfection case were detected. In contrast, only 11.67% (n = 14) of wild boars tested negative for PCV2 and PCV3 (92 tested positive for PCV2, 66 for PCV3, and 52 for both).

The positivity rate in domestic pigs varied by production stage, with PCV2 present only in early stages of production (nursery and fattening), while PCV3 was found in all groups (

Table 2).

Compared to our 2023 study [

5], which focused solely on domestic pigs, both PCV2 and PCV3 infection rates appear to have declined: PCV2 decreased from 3.2% to 1.9% and PCV3 decreased from 19.4% to 11.2%. Concerning wild boar, samples from 2023 to 2025 were included in this study. The results were similar, showing a decrease in infection rates for both viruses: PCV2 declined from 93.3% in 2023 to 71.2% in 2024, and PCV3 showed a small reduction from 66.7% to 51.7. The coinfection level declined from 63.3% to 37.1%. These results are summarized in

Table 2.

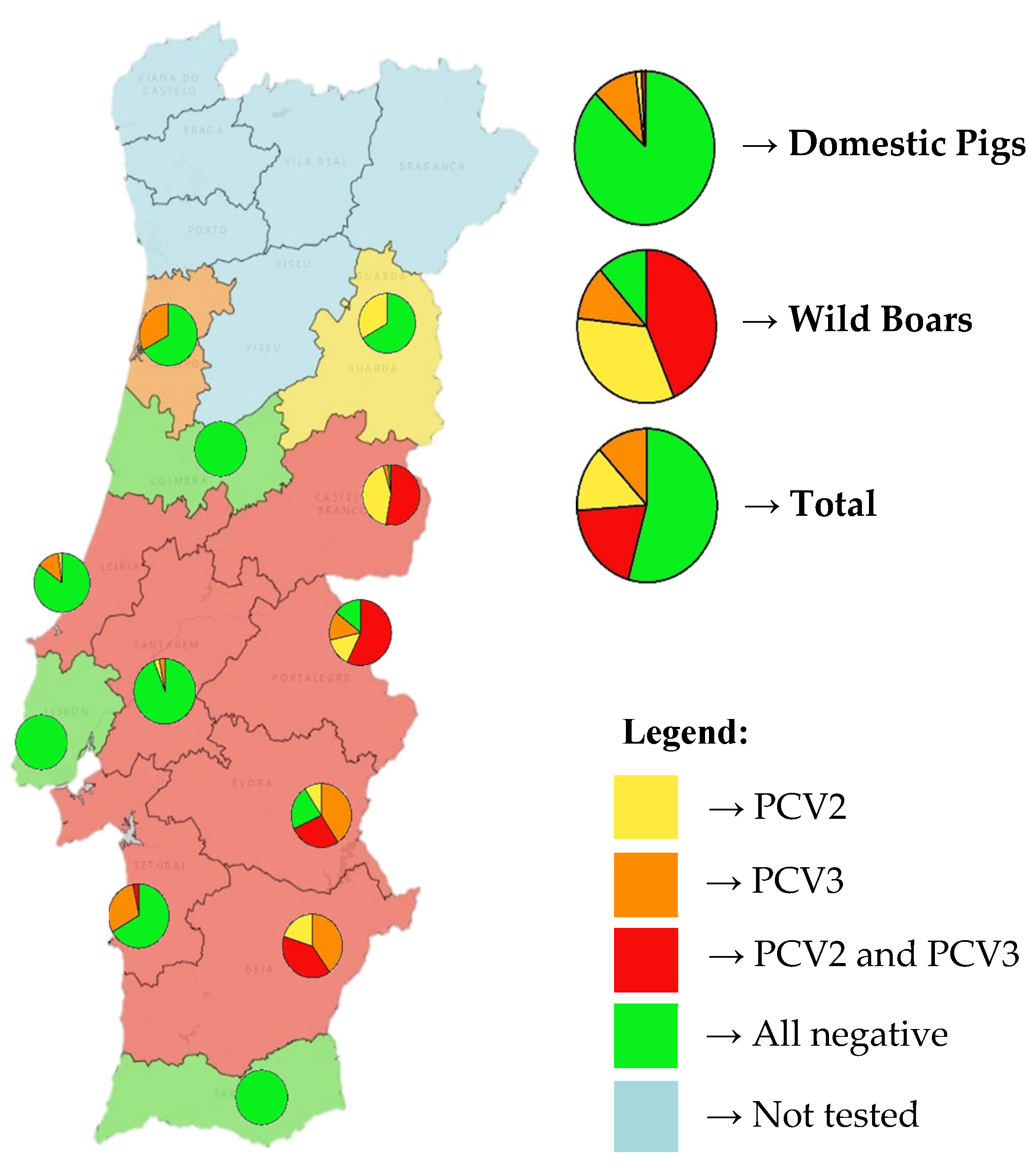

Figure 1 shows the distribution of both viruses in Portugal. Nine of the twelve tested mainland Portuguese districts had at least one virus present, with only three districts (Aveiro, Lisbon, and Faro) showing no detection of either virus. Additionally, a higher prevalence of both viruses can be seen in eastern districts, likely because most of the tested wild boars came from these regions. The districts of Castelo Branco, Portalegre, Évora, and Beja displayed the highest prevalence of coinfection, exceeding 50% in some cases.

In the districts where only domestic pigs were tested, it is important to note that one-third of the animals in the districts of Setúbal and Leiria were infected, primarily with PCV3.

Among domestic pigs, PCV3 was the most prevalent virus (11.2%), followed by low rates of PCV2 (1.9%) and coinfection (0.6%). In contrast, wild boars had markedly higher detection rates for all categories: 76.7% for PCV2, 55.0% for PCV3, and 43.3% for coinfections.

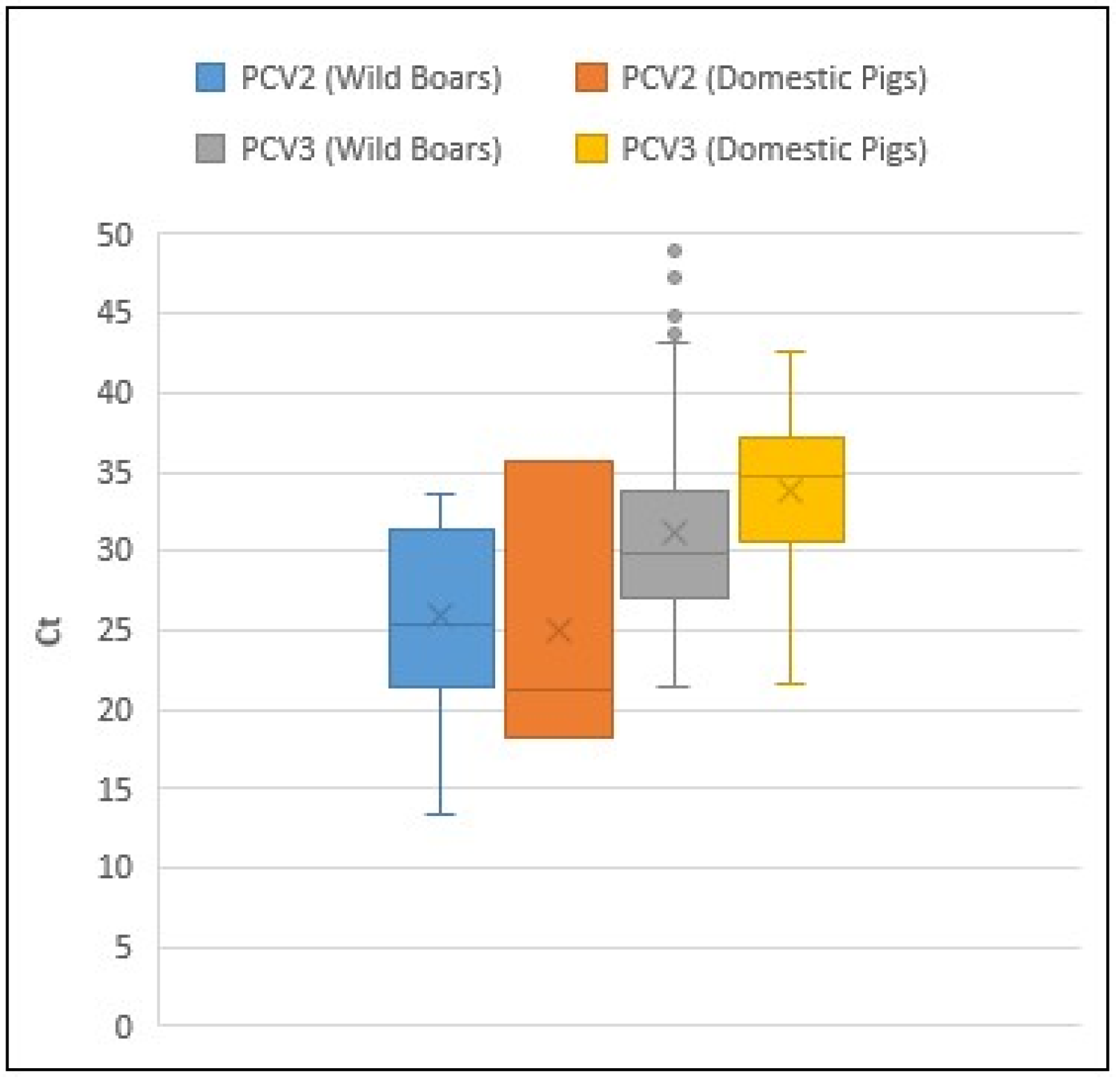

A comparative analysis of the Ct values obtained for PCV2 and PCV3 in wild boars and domestic pigs was conducted using box-and-whisker plots (

Figure 2).

Although no direct studies have been published on PCV2 and PCV3, research on related viruses that infect domestic pigs and wild boars, such as PCV4 and HEV, [

10,

11] has shown that Ct values obtained via qPCR from feces and organs, such as the liver, kidneys, diaphragm, spleen, and lungs, are comparable within the same animal. These results suggest that viral load assessments are consistent across these sample types, supporting the assumption that PCV2 and PCV3 behave similarly in terms of viral load distribution.

For PCV2, however, robust comparisons are limited due to the small number of positive cases detected in domestic pigs (n = 3). However, it is noteworthy that the average Ct values were similar between wild boars and domestic pigs (25.84 and 25.00, respectively).

In contrast, the average PCV3 Ct value was higher in domestic pigs (33.75) than in wild boars (31.15), as was the median (34.75 and 29.81, respectively). This suggests a lower viral load in the domestic pig population. However, this difference is not statistically significant (p > 0.05), as determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test using IBM SPSS software.

On the other hand, and although comparison of Ct values obtained with different qPCR systems are not totally reliable, the Ct values obtained with positive PCV2 samples were consistently lower than those obtained with PCV3 positive samples, suggesting a higher viral charge of PCV2 in their host samples. Indeed, the Ct values of PCV2- positive samples from wild boars are statistically lower than those of the Ct values of PCV3 samples in both domestic pigs and wild boars. Due to the small number of PCV2- positive domestic pigs, this group is not statistically different from any other group of pigs.

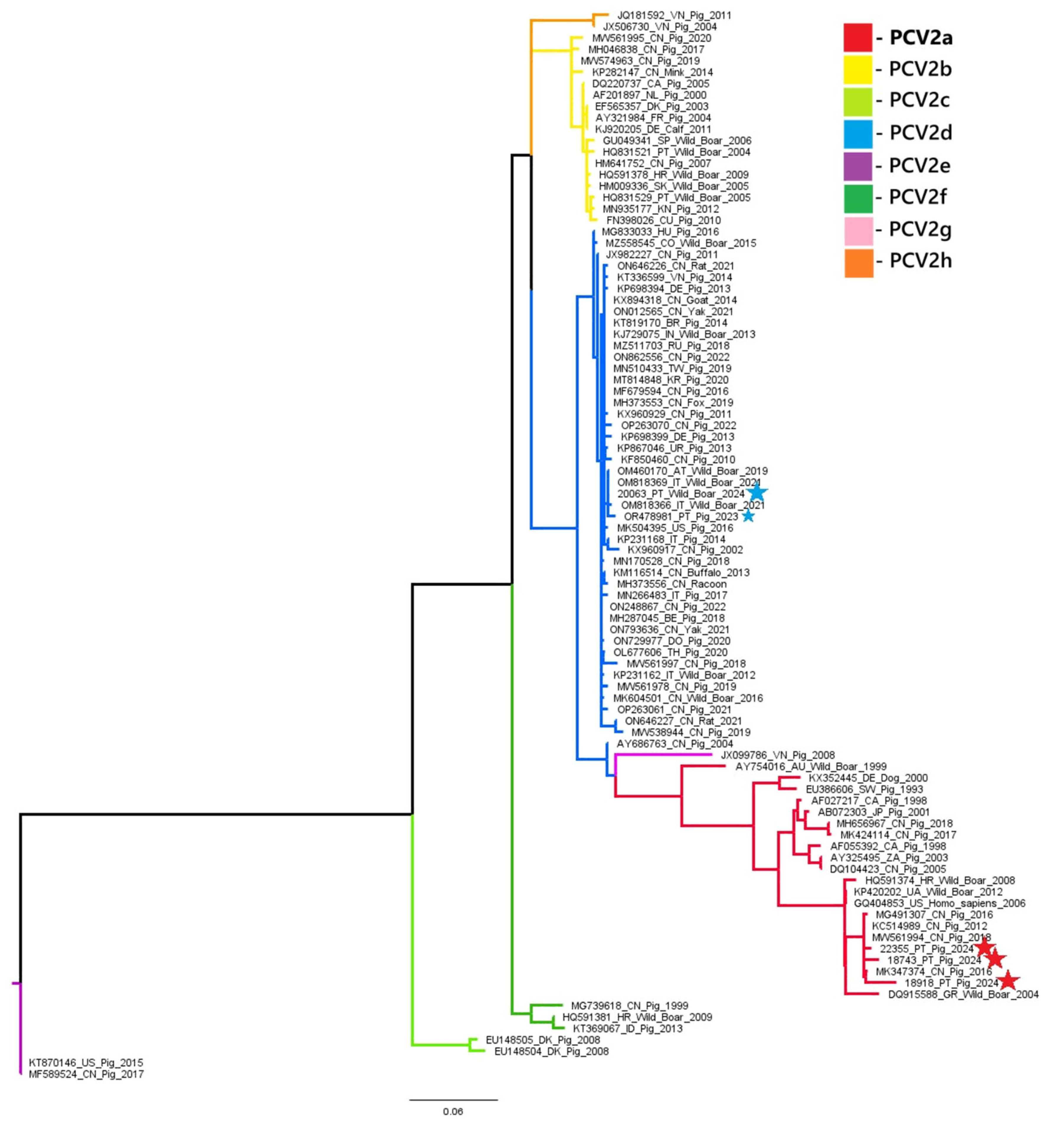

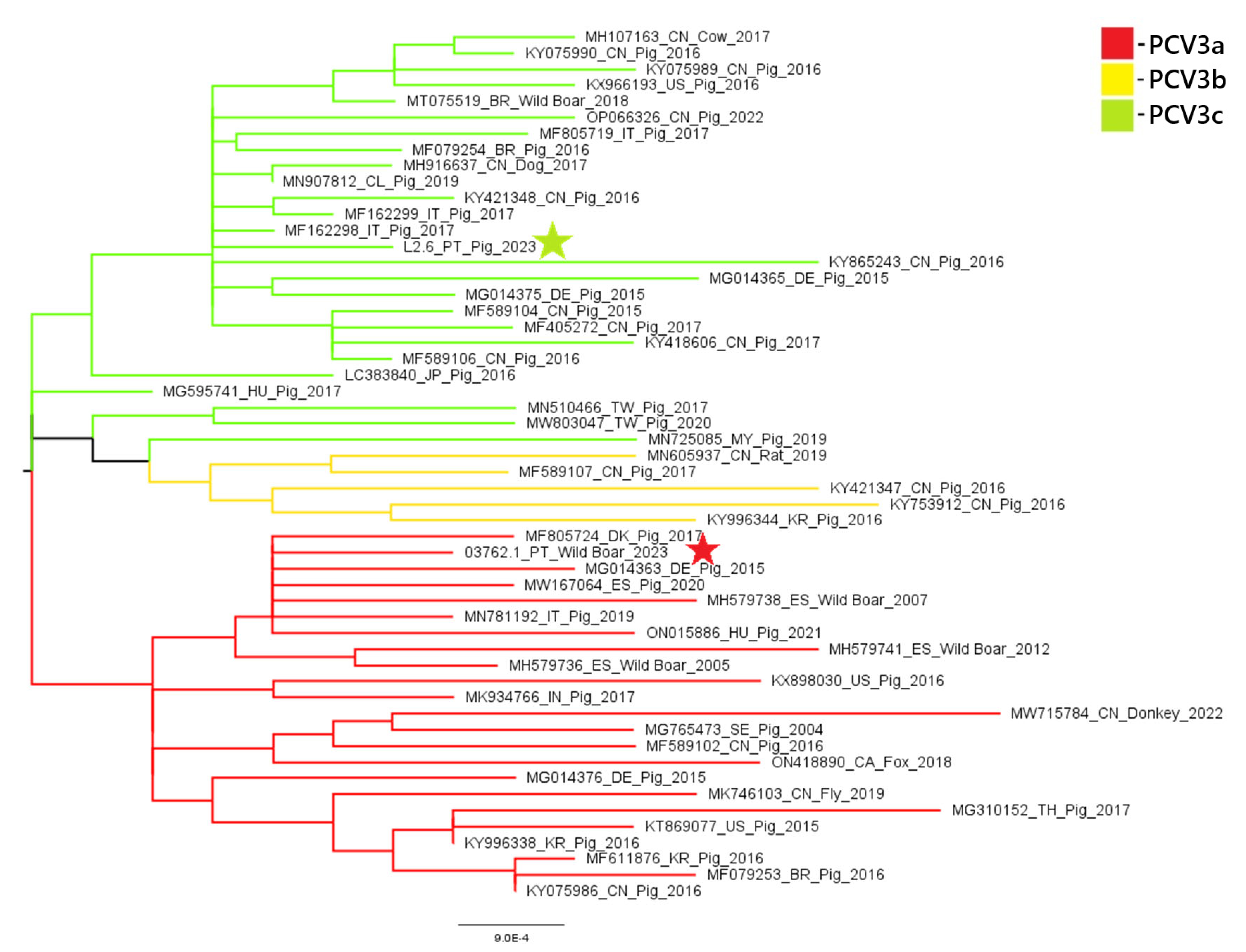

A phylogenetic analysis of PCV2 and PCV3 nucleotide sequences revealed distinct genotypic distributions between domestic pigs and wild boars. All three PCV2 sequences obtained from domestic pigs (samples 18743, 18918, and 22355) belonged to the PCV2a genotype. In contrast, the PCV2 sequence from a wild boar (sample 20063) belonged to the PCV2d genotype. These results suggest that there is diversity in genotypes between the two populations. Similarly, the PCV3 sequence from the domestic pig (sample L2.6) belonged to PCV3c, while the wild boar sequence (sample 03762.1) was classified as PCV3a. These results indicate the circulation of different PCV3 genotypes across hosts. These findings are illustrated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

4. Discussion

This study sheds new light on the epidemiology and viral load dynamics of PCV2 and PCV3 in wild boars and domestic pigs in different regions of mainland Portugal. By comparing the prevalence of coinfection, and qPCR Ct values across host subspecies, production stages, and geographic locations, the results contribute valuable data on the circulation of porcine circovirus circulation in both domestic and wild populations.

A key finding was the higher prevalence of both PCV2 and PCV3 in wild boars than in domestic pigs. While only 12.5 % of domestic pigs tested positive for at least one virus, 88.3% of wild boars were infected with PCV2, PCV3, or both. Coinfection was particularly prevalent in wild boars, affecting 43.3% of them, primarily in the districts of Castelo Branco and Portalegre, as opposed to 0.6% of domestic pigs. These differences reflect the lack of vaccination in wild boar populations, as well as potential differences in environmental exposure, showing how farm biosecurity policies effectively limit pathogen spread.

Within domestic pigs, viral distribution varied according to production stage. PCV2 was only detected in nursery and fattening pigs (pigs less than six months old), which aligns with previous studies showing early-life susceptibility to PCV2 infection, possibly due to waning maternal antibodies [

10]. In contrast, PCV3 was found across all production stages, suggesting a broader distribution or a longer persistence within domestic herds.

Geographically, the presence of the two viruses was detected in 9 out of 12 sampled districts of mainland Portugal. The eastern regions, particularly Castelo Branco, Portalegre, Évora, and Beja, exhibited the highest coinfection rates, surpassing 50% in certain areas. This is likely due to the greater number of wild boars sampled from these districts. Interestingly, notable levels of coinfection were observed even in some districts where only domestic pigs were tested, such as Setúbal and Leiria.

These results highlight the importance of regional monitoring and indicate possible environmental or management-related risk factors.

Ct value analysis provided further insight into viral load differences. Although sample types differed (feces in pigs vs. tissues in wild boars), existing literature on similar viruses (e.g., PCV4 and HEV) supports the comparability of qPCR Ct values across these matrices. PCV3 Ct values were higher in domestic pigs than in wild boars, suggesting a lower viral load in the domestic population. For PCV2, robust comparisons were limited due to the small number of positive domestic pig samples (n=3), but average Ct values were similar between the pig groups. These observations reinforce the value of viral load analysis for understanding infection dynamics, while also emphasizing the need for more extensive sampling in domestic pigs.

A comparison with our previous study conducted in 2023 revealed a decrease in the infection rates of both PCV2 and PCV3 in the pig population with PCV2 positivity dropping from 3.2% to 1.9%, and PCV3 from 19.4% to 11.2%. In the wild boar population, the prevalence of these viruses behaved similarly when comparing 2023 with 2024 samples, showing a reduction in the PCV2 (from 93.3% to 71.2%) and PCV3 (from 66.7% to 51.7%) prevalence with a notable decline in coinfection rates (from 63.3% to 37.1%). These trends may reflect real epidemiological changes as a result of improved biosecurity measures in farms or temporal variation.

Coinfection, especially in wild boars, remains an important concern. The high rate of coinfection found in wild boar raises questions about their role as PCV2 and PCV3 reservoirs and source for ongoing transmission to domestic pigs.

A key observation in this study is the low PCV2 infection rate among domestic pig populations showcasing the effectiveness of PCV2 vaccination programs, with PCV3 infection rate being significantly higher (1.9% for PCV2 and 11.2% for PCV3). This finding contrasts with the situation in wild boars’ population, where PCV2 infection rate reaches 76.7%, due to the absence of vaccination in these wild populations.

Concerning PCV3, a similar infection rate was expected in both domestic pigs and wild boars as none are vaccinated against this virus in Portugal. However, the observed discrepancy, with infection rates in wild boars (55.0%) nearly five times higher than in domestic pigs (11.2%), raises questions about a putative interplay between PCV2 vaccination and PCV3 infection in domestic pigs. Our results suggest that PCV2 vaccine may offer protection against subsequent PCV3 infection, although the opposite is indicated in literature.

Although vaccination does not prevent infection, PCV2 vaccination may influence the immune response in pigs, potentially reducing PCV3 replication and viral load, providing a quicker disease recovery and virus elimination. This could potentially explain the lower prevalence of PCV3 in domestic pigs compared to wild boars, as the PCV2 vaccine could limit the amount of PCV3 circulating in the pigs. This would also explain the higher Ct values observed in domestic pigs compared to wild boars. Nonetheless, this hypothesis requires experimental confirmation in future studies to fully understand the interactions between PCV2 and PCV3 in terms of viral dynamics and immune responses.

Overall, this study highlights the continued circulation of PCV2 and PCV3 in both domestic pigs and wild boars in Portugal, with wild boars showing significantly higher infection and coinfection rates than domestic pigs. These findings emphasize the importance of integrating wildlife surveillance into national swine health programs and provide a foundation for future studies investigating transmission dynamics, control strategies, and the potential impact of these viruses on animal health and production.

Phylogenetic analysis of the PCV2 and PCV3 nucleotide sequences obtained in this study highlighted distinct genotype distributions between different host species. All three PCV2 sequences obtained from domestic pigs were classified as PCV2a, while the wild boar sequence was identified as PCV2d. This contrasts with our previous data from 2023 [

5], where the PCV2 genotype circulating in domestic pigs was PCV2d. The absence of PCV2d in the current pig samples may represent a shift in genotype prevalence, local eradication of PCV2d in vaccinated populations, or sampling variation due to the limited number of sequenced samples.

Concerning PCV3, our findings are more consistent with previous data: the domestic pig sample clustered within the PCV3c genotype—aligning with the dominant strain reported in pigs in 2023 [

5], while wild boar positive samples showed to belong to PCV3a, a genotype previously identified in wildlife in other European countries, namely in Italy, Sardinia and in Germany [

11,

12]. This pattern may reflect host-specific circulation of genotypes, with PCV3c potentially adapting better to domestic pigs (subspecies

Sus scrofa domesticus) and PCV3a being more prevalent in wild boar populations (species

Sus scrofa).

These findings, although limited by the small number of samples sequenced raise the possibility of genotype segregation between domestic and wild populations and emphasize the importance of continuous molecular surveillance. Future studies with larger PCV sequence datasets from domestic and wild Suidae will help trace the emergence and spread of the different genotypes, explore the role of wild boars in virus transmission, and evaluate how factors like vaccination and environmental persistence may influence viral evolution.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study provides valuable insights into the viral dynamics of PCV2 and PCV3 in domestic pigs and wild boars in mainland Portugal, suggesting a possible impact of PCV2 on PCV3 infections due to vaccination programs.

Furthermore, our results confirm the effectiveness of the PCV2 vaccination program in domestic pigs, as evidenced by the lower infection rate (1.9%) compared to the unvaccinated wild boar population (76.7%). In contrast, PCV3 infection was present in both Suidae groups, with wild boars showing a significantly higher infection rate than domestic pigs, despite the fact that vaccination against PCV3 is not practiced in Portugal.

These findings suggest that vaccinating domestic pigs against PCV2 could reduce PCV3 viral load during infection, potentially by limiting virus replication. Further research is needed to better understand the immune dynamics and viral interactions during PCV2 and PCV3 infections, as supported by the trend differences in Ct values between the two populations and this apparent interference. PCV2a and PCV3c genotypes were identified in domestic pig samples, whereas PCV2d and PCV3a genotypes were identified in wild boar samples. These results contrast with previous findings from Portugal in 2023, where PCV2d was found to be the predominant strain circulating in domestic pigs [

5]. The detection of distinct genotypes circulating independently in wild boars may reflect host-specific viral evolution or different transmission networks. This finding underscores the importance of ongoing surveillance of PCV2 and PCV3 in domestic and wild pig populations, particularly in areas with higher coinfection rates, to identify the circulating genotypes, which will provide additional context for the current laboratory findings. In addition to industrial domestic pigs and wild boars, investigations should target traditional free-range Iberian pigs, as they represent a critical epidemiological interface between the two groups.

These animals often share habitats with wild boars while maintaining indirect links to intensive farming systems through human management, making them a potential epidemiological bridge for the transmission of pathogens. This approach is essential to confirm the hypothesis that there is an apparent segregation of genotypes among domestic and wild pigs. Investigations should also focus on exploring potential cross-virus interactions and the implications of PCV2 and PCV3 genotypes on pig health, disease management, and meat production efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and A.M.H.; methodology, B.A., M.D.D., A.D., S.C.B, F.A.S, A.M.H.; software, B.A.; formal analysis, B.A., M.D.D., A.D., T.F., F.R., T.L., I.C., S.C.B, F.A.S, A.M.H.; investigation, B.A., M.D.D., A.D., T.F., F.R., T.L., I.C., S.C.B, F.A.S, A.M.H.; resources, A.D., A.M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.H., M.D.D.; supervision, A.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author, however the right to privacy of the property owners will be respected.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Carla Carvalho for making available wild boars tissue samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| °C |

Degrees Celsius |

| µL |

Microliter |

| µM |

Micromolar |

| bp |

Base pairs |

| Ct |

Cycle threshold |

| F |

Forward |

| FAM |

6-carboxyfluorescein |

| HEV |

Hepatitis E virus |

| HSD |

Honestly Significant Difference |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PCV2 |

Porcine Circovirus type 2 |

| PCV3 |

Porcine Circovirus type 3 |

| PCV4 |

Porcine Circovirus type 4 |

| PCVAD |

Porcine circovirus-associated diseases |

| qPCR |

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| R |

Reverse |

| w/v |

Weight per volume |

| ×g |

Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF) |

References

- Segalés, J. Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2) Infections: Clinical Signs, Pathology and Laboratory Diagnosis. Virus Res. 2012, 164, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccini, S.; Barbieri, I.; Gilioli, A.; Sala, G.; Gibelli, L.R.; Moreno, A.; Sacchi, C.; Rosignoli, C.; Franzini, G.; Nigrelli, A. Detection and Genetic Characterization of Porcine Circovirus Type 3 in Italy. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1661–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czyżewska-Dors, E.; Núñez, J.I.; Saporiti, V.; Huerta, E.; Riutord, C.; Cabezón, O.; Segalés, J.; Sibila, M. Detection of Porcine Circovirus 3 in Wildlife Species in Spain. Pathogens 2020, 9, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadejek, T.; Woźniak, A.; Miłek, D.; Biernacka, K. First Detection of Porcine Circovirus Type 3 on Commercial Pig Farms in Poland. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1350–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, B.; Marçal, S.; Duarte, M.D.; Duarte, A.; Fagulha, T.; Ramos, F.; Barros, S.C.; Luís, T.; Henriques, A.M. Molecular Detection of Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and 3 in Pig Farms: First Report of PCV3 in Portugal. Curr. Top. Virol. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Klaumann, F.; Correa-Fiz, F.; Giovanni, F.; Sibila, M.; Núñez, J.I.; Segalés, J. Current Knowledge on Porcine circovirus 3 (PCV-3): A Novel Virus With a Yet Unknown Impact on the Swine Industry. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.M. da C.G.R. Avaliação de um programa de vacinação de circovirose suína numa exploração de produção intensiva. Master thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, 2017.

- Henriques, A.M.; Duarte, M.; Fagulha, T.; Ramos, F.; Barros, S.C.; Luís, T.; Fevereiro, M. Molecular study of porcine circovirus type 2 circulating in Portugal. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.J.; Lindsay, D.S.; Sriranganathan, N. Wild Boars as Sources for Infectious Diseases in Livestock and Humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2697–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, J.; Opriessnig, T.; Meng, X.J.; Pelzer, K.; Buechner-Maxwell, V. Porcine Circovirus Type 2 and Porcine Circovirus-Associated Disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dei Giudici, S.; Franzoni, G.; Bonelli, P.; Angioi, P.P.; Zinellu, S.; Deriu, V.; Carta, T.; Sechi, A.M.; Salis, F.; Balzano, F.; et al. Genetic Characterization of Porcine Circovirus 3 Strains Circulating in Sardinian Pigs and Wild Boars. Pathogens 2020, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, C.; Stillfried, M.; Neubert, L.K.; Denner, J. Detection of PCV3 in German Wild Boars. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution and prevalence of PCV2 and PCV3 in mainland Portugal. Districts are color-coded according to virus presence: yellow for PCV2-positive, orange for PCV3-positive, red for PCV2 and PCV3 coinfection, green for negative results, and blue for untested districts. On top of each tested district, a pie chart illustrates the proportions of PCV2-positive (yellow), PCV3-positive (orange), coinfection (red), and negative (green) samples. On the right side of the map, three larger pie charts display the same viral distribution by host category: domestic pigs (top), wild boars (middle), and the combined total of both populations (bottom).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution and prevalence of PCV2 and PCV3 in mainland Portugal. Districts are color-coded according to virus presence: yellow for PCV2-positive, orange for PCV3-positive, red for PCV2 and PCV3 coinfection, green for negative results, and blue for untested districts. On top of each tested district, a pie chart illustrates the proportions of PCV2-positive (yellow), PCV3-positive (orange), coinfection (red), and negative (green) samples. On the right side of the map, three larger pie charts display the same viral distribution by host category: domestic pigs (top), wild boars (middle), and the combined total of both populations (bottom).

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots showing qPCR Ct values of positive samples from wild boar and domestic pigs for PCV2 and PCV3. Blue and orange represent PCV2-positive samples from wild boar and domestic pigs, respectively; grey and yellow represent PCV3-positive samples from wild boar and domestic pigs, respectively. For PCV2, only three domestic pig samples were positive, limiting the strength of direct comparisons. The "×" symbol above each box plot indicates the average Ct value for each group.

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots showing qPCR Ct values of positive samples from wild boar and domestic pigs for PCV2 and PCV3. Blue and orange represent PCV2-positive samples from wild boar and domestic pigs, respectively; grey and yellow represent PCV3-positive samples from wild boar and domestic pigs, respectively. For PCV2, only three domestic pig samples were positive, limiting the strength of direct comparisons. The "×" symbol above each box plot indicates the average Ct value for each group.

Figure 3.

PCV2 phylogenetic tree was built using Maximum Likelihood method and TIM2+F+I+G4 (Transitional model 2) model (identified as the best-fit substitution model in MEGA X). Sequences marked with a big star represent samples obtained in the present study. Sequence marked with a small blue star originated from a sample of our previous study.

Figure 3.

PCV2 phylogenetic tree was built using Maximum Likelihood method and TIM2+F+I+G4 (Transitional model 2) model (identified as the best-fit substitution model in MEGA X). Sequences marked with a big star represent samples obtained in the present study. Sequence marked with a small blue star originated from a sample of our previous study.

Figure 4.

PCV3 phylogenetic tree was built using Maximum Likelihood method and TN+F+I+G4 (Tamura-Nei) model (identified as the best-fit substitution model in MEGA X). Sequences marked with a star represent samples obtained in the present study.

Figure 4.

PCV3 phylogenetic tree was built using Maximum Likelihood method and TN+F+I+G4 (Tamura-Nei) model (identified as the best-fit substitution model in MEGA X). Sequences marked with a star represent samples obtained in the present study.

Table 1.

Primers and probes sequences used for the detection of PCV2 and PCV3 by qPCR and conventional PCR. For each reaction, the corresponding forward (F), reverse (R), and probe (when applicable) sequences are listed in 5′ to 3′ orientation. Fluorescent labeling with FAM was used for qPCR probes.

Table 1.

Primers and probes sequences used for the detection of PCV2 and PCV3 by qPCR and conventional PCR. For each reaction, the corresponding forward (F), reverse (R), and probe (when applicable) sequences are listed in 5′ to 3′ orientation. Fluorescent labeling with FAM was used for qPCR probes.

| Reaction |

Name |

Sequence |

| qPCR PCV2 |

PCV2-PT-rep6(F) |

5’ - CAG CAA GAA GAA TGG AAG - 3' |

| PCV2-PT-rep149(R) |

5' - TTA CCC TCC TCG CCA AC - 3' |

| PCV2-PT probe(R) |

5’ - [FAM]TCC CGT ATT TTC TTG CGC TCG TCT TC - 3 |

| qPCR PCV3 |

PCV3_real_FW |

5’ - AGT GCT CCC CAT TGA ACG - 3' |

| PCV3_real_RV |

5' - ACA CAG CCG TTA CTT CAC - 3' |

| PCV3_real_probe |

5’ - [FAM]ACC CCA TGG CTC AAC ACA TAT GAC C - 3' |

| PCR PCV2 |

S4 |

5' – CAC GGA TAT TGT AGT CCT GGT - 3' |

| AS4 |

5' - CCG CAC CTT CGG ATA TAC TGT C - 3' |

| PCR PCV3 |

PCV3_seq2_FW |

5' - GTC GTC TTG GAG CCA AGT G - 3' |

| PCV3_seq2_RV |

5’ - CGA CCA AAT CCG GGT AAG C - 3' |

Table 2.

Distribution of PCV2, PCV3, and coinfection cases among different pig production stages and wild boars. The number of tested animals, age range, and infection rates (in absolute numbers and percentages) are indicated for each group. Percentages represent the proportion of infected animals within each group.

Table 2.

Distribution of PCV2, PCV3, and coinfection cases among different pig production stages and wild boars. The number of tested animals, age range, and infection rates (in absolute numbers and percentages) are indicated for each group. Percentages represent the proportion of infected animals within each group.

| Group |

Epidemiological unit |

Year of sampling |

Age |

Number of tested animals |

PCV2

infection |

PCV3

infection |

PCV2 and PCV3

coinfection |

| Domestic pig |

Quarantine |

2024 |

Any |

5 |

0 |

1 (20.0%) |

0 |

| Nursery |

3 to 10 weeks |

24 |

1 (4.2%) |

3 (12.5%) |

1 (4.2%) |

| Fattening |

10 weeks to 6 months |

28 |

2 (7.1%) |

3 (10.7%) |

0 |

| Breeding Stalls |

More than 7 months |

21 |

0 |

1 (4.8%) |

0 |

| Gestation |

More than 7 months |

44 |

0 |

3 (6.8%) |

0 |

| Maternity |

More than 8 months |

38 |

0 |

7 (18.4%) |

0 |

| Total Pig |

|

- |

160 |

3 (1.9%) |

18 (11.2%) |

1 (0.6%) |

| Wild Boar |

N/A |

2023 |

Unknown |

30 |

28 (93.3%) |

20 (66.7%) |

19 (63.3%) |

| 2024 |

Unknown |

89 |

64 (71.2%) |

46 (51.7%) |

33 (37.1%) |

| 2025 |

Unknown |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Total Wild Boar |

|

- |

120 |

92 (76.7%) |

66 (55.0%) |

52 (43.3%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).