1. Introduction

Ebola Sudan virus (SUDV), one of the members of the genus Ebolavirus, is responsible for recurrent epidemic outbreaks in sub-Saharan Africa, characterized by high lethality and significant socioeconomic impact [

1]. SUDV is genetically distinct from other members of the Ebolavirus genus, with a nucleotide divergence of about 35-45% compared to the well-known Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) [

2]. More importantly, it also shows differences in antigenicity and pathogenicity [

3]. This places it in a separate clade in the Ebolavirus phylogenetic tree. Phylogenetic analysis of outbreaks has revealed that SUDV evolves at a mutation rate similar to other Ebolavirus species, estimated to be around 8 × 10

−4 substitutions per site per year [

4]. However, unlike EBOV, which showed a greater capacity for adaptation and human-to-human transmission during the 2014-2016 outbreak, SUDV has historically caused more localized outbreaks with lower transmissibility [

5]. The various SUDV strains identified so far show significant genetic variability between outbreaks, suggesting independent emergence events rather than sustained human-to-human transmission. This supports the hypothesis of a natural reservoir for the virus, likely in fruit bats, although the exact reservoir has not yet been confirmed [

6]. Historically, SUDV outbreaks have been less frequent than EBOV outbreaks but have still caused major epidemics, such as those in Uganda in 2000, 2011, and 2014 [

7]. Unlike EBOV, which saw widespread during the 2014-2016 West African outbreak [

8], SUDV has remained predominantly confined to specific regions, with limited but highly lethal transmission. In 2022, Uganda experienced a new outbreak of SUDV, characterized by rapid spread in several regions of the country and a mortality rate of more than 34% [

9]. This outbreak posed a significant challenge to local health systems, highlighting the need for a rapid and coordinated response. Three years later, in 2025, a second SUDV outbreak emerged in Uganda, raising questions about transmission dynamics, viral evolution, and outbreak response capabilities [

10]. The aim of our research is to provide an integrative perspective that considers both epidemiological and genetic data in order to enhance our understanding of the current outbreak.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We conducted a retrospective observational study to analyze the epidemiological trends, transmission dynamics, and genomic characteristics of Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV) outbreaks in Uganda from 2000 to 2025. The study population includes all laboratory-confirmed SUDV cases reported in this time frame, with detailed stratification by geographic location and occupational exposure (e.g., healthcare workers). Our analysis focuses on spatiotemporal variations in outbreak severity and case fatality rates (CFRs) by district, exploring patterns over time and space to identify high-risk areas. Moreover, to explore the mechanisms driving outbreak persistence and viral adaptation, we supplement epidemiological surveillance with high-resolution phylogenomic analyses. This allows us to perform a comparative assessment of viral evolution over multiple epidemic periods, identifying potential genetic mutations associated with changes in transmissibility, pathogenicity, or immune escape.

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Data collection follows standardized epidemiological and genomic protocols to ensure consistency across different outbreak periods. Retrospective data sources include a range of different sources to update and curate our open-access database [

11]. First, for the epidemiological data, we use official government sources that report primary data as the gold standard for data inclusion. Government sources include press releases on the official websites of Ministries of Health and World Health Organization African Region, as well as updates provided by the official social media accounts of governmental or public health institutions. Second, to find additional details for each case or patient we augment these data with online reports, mainly captured through the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP), a leading global resource for infectious disease news and analysis (i.e.,

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/ebola) or via news aggregators (e.g.,

https://bnonews.com/index.php/tag/ebola).

Genomic sequencing of SUDV-positive samples is conducted to analyze viral evolution, with comparisons to previous outbreak strains. The genomic dataset was built by downloading all available sequences from the Pathoplexus databank, section Ebola Sudan (

https://pathoplexus.org/ebola-sudan/search?). The final dataset consisted of 166 genomic sequences isolated between 1976 and January 19, 2025. The entire dataset was aligned using the MAFFT [

12] software and manually checked with UGene Pro [

13]. To explore the variability of Ebola Sudan strain lineage over an extended timeframe, all genomes were analyzed using Bayesian Inference (BI) with BEAST 1.10.4 [

14]. The analysis involved 200 million generations under different demographic and clock models. The most suitable model was selected based on Bayes Factor testing [

15], comparing 2lnBF values of marginal likelihoods using the software Tracer 1.7 [

16]. The obtained tree was edited and visualized using FigTree 1.4.0 (

http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). In order to examine genetic structure, detect potential subgroups within genetic clusters, and evaluate genetic variability among isolates, the Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) was conducted using GenAlEx 6.5 [

17]. This analysis aimed to measure dissimilarity based on the genetic variation present in the analyzed isolates. The PCoA reconstruction relied on a pairwise p-distance matrix derived from genetic data, estimated over 1000 iterations using the R package APE [

18]. The analysis was finalized by applying the PCoA method through a covariance matrix with data standardization.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological Analysis

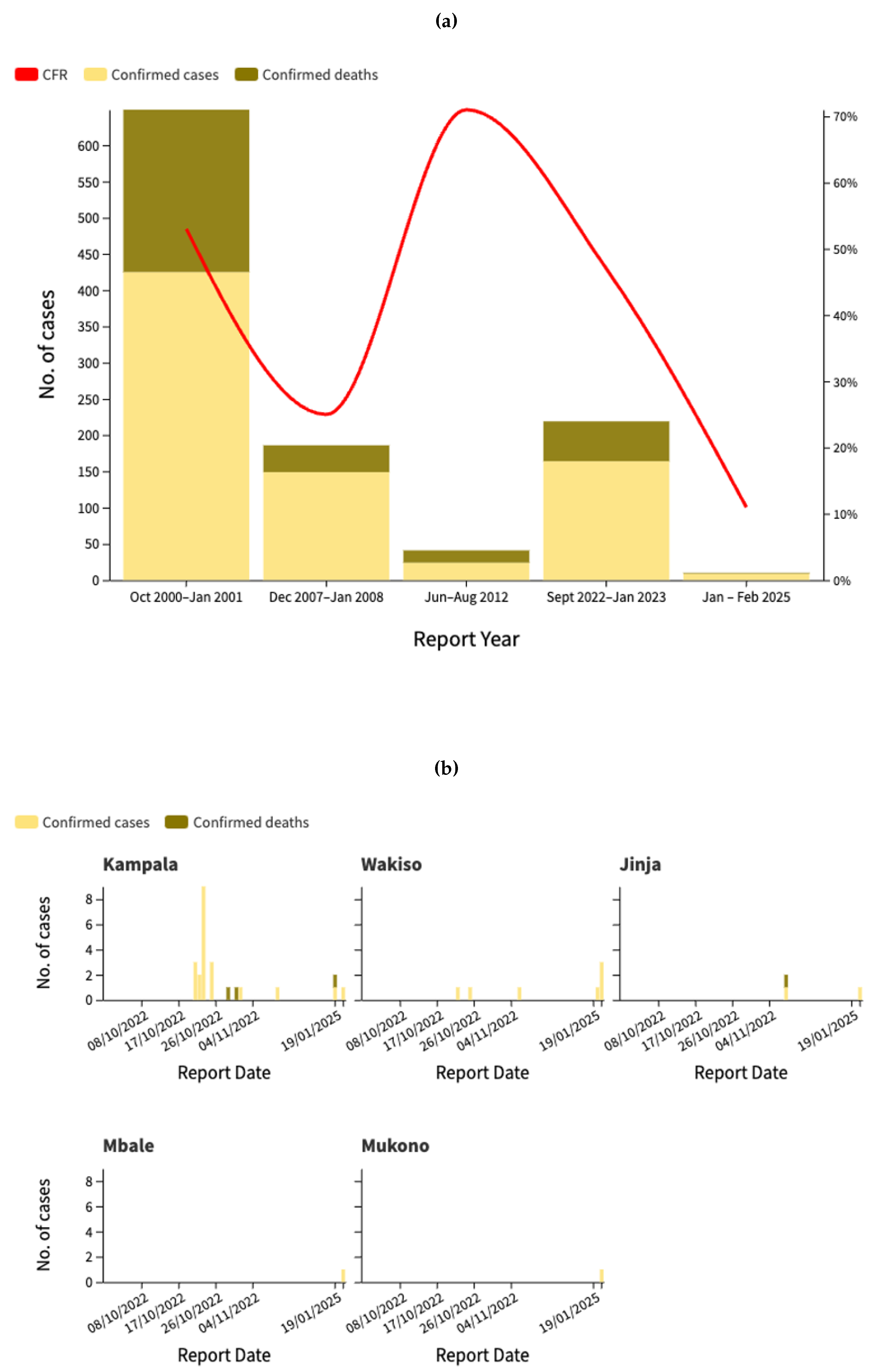

Uganda has experienced multiple Ebola outbreaks over the past two decades, with varying degrees of severity in terms of cases and fatalities, as described in

Figure 1a. The most severe outbreak occurred between October 2000 and January 2001, with 425 confirmed cases and a case fatality rate (CFR) of 52.7%. While some outbreaks, such as that of 2012, had higher mortality rates (70.8%), the total number of cases was significantly lower. The outbreak in 2022-2023 was the largest in recent years, with 164 confirmed cases and a CFR of 33.5%, showing significant variations in case distribution across districts (

Figure 1b). The highest number of confirmed cases has been reported in Kassanda District (45 cases, 21 deaths), followed by Mubende District (32 cases, 20 deaths). Kampala, the capital city, has recorded 19 cases and two deaths, underscoring the potential for urban spread. Other affected districts include Wakiso (4 cases), Jinja, Kagadi, Kyegegwa, and Masaka, each reporting one confirmed case and one death. The presence of cases in multiple districts highlights the risk of regional transmission, necessitating stringent surveillance, early identification, and robust infection control measures to curb further spread. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 1c, the epidemiological curve of the 2022 outbreak reveals a significant difference in case distribution between healthcare workers and non-healthcare workers. The outbreak peaked in late October 2022, with the highest daily count of 17 cases reported on October 23, predominantly affecting non-healthcare workers. Healthcare workers represented a smaller but consistent proportion of cases throughout the outbreak, with several clusters identified in late October and mid-November. This pattern of transmission suggests both community spread and nosocomial transmission, with healthcare workers facing continued occupational exposure risks. After December 2022, case numbers declined significantly until the Ministry of Health of Uganda notified WHO of a new SUDV outbreak on 30 January 2025 following the confirmation of a case in the capital city, Kampala [

19], marking the start of a new phase of the Ebola in Uganda, as illustrated in

Figure 1d. As of February 20, 2025, the Ebola virus disease outbreak in Uganda has recorded a total of nine confirmed cases and one death, with a lethality rate of 11%. The cases were reported in four districts-Kampala, Wakiso, Mbale, and Jinja. Eight patients were discharged from treatment centers on February 18 after receiving two negative tests 72 hours apart. Currently, 58 contacts are still being monitored in designated quarantine facilities in Jinja, Kampala and Mbale districts [

20].

Figure 1.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. All nodes are fully supported for Posterior Probabilities (PP). The terminal labeled in red font represent the only one available for the new current outbreak in Uganda. (b) Principal coordinate analysis of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. The cumulative variability explained by the first three axes amounts to 92.97% (Axis1: 43.85%, Axis2: 21.22%, Axis3: 18.89%) The groups were set a priori in accordance with the sampling locality.

Figure 1.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. All nodes are fully supported for Posterior Probabilities (PP). The terminal labeled in red font represent the only one available for the new current outbreak in Uganda. (b) Principal coordinate analysis of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. The cumulative variability explained by the first three axes amounts to 92.97% (Axis1: 43.85%, Axis2: 21.22%, Axis3: 18.89%) The groups were set a priori in accordance with the sampling locality.

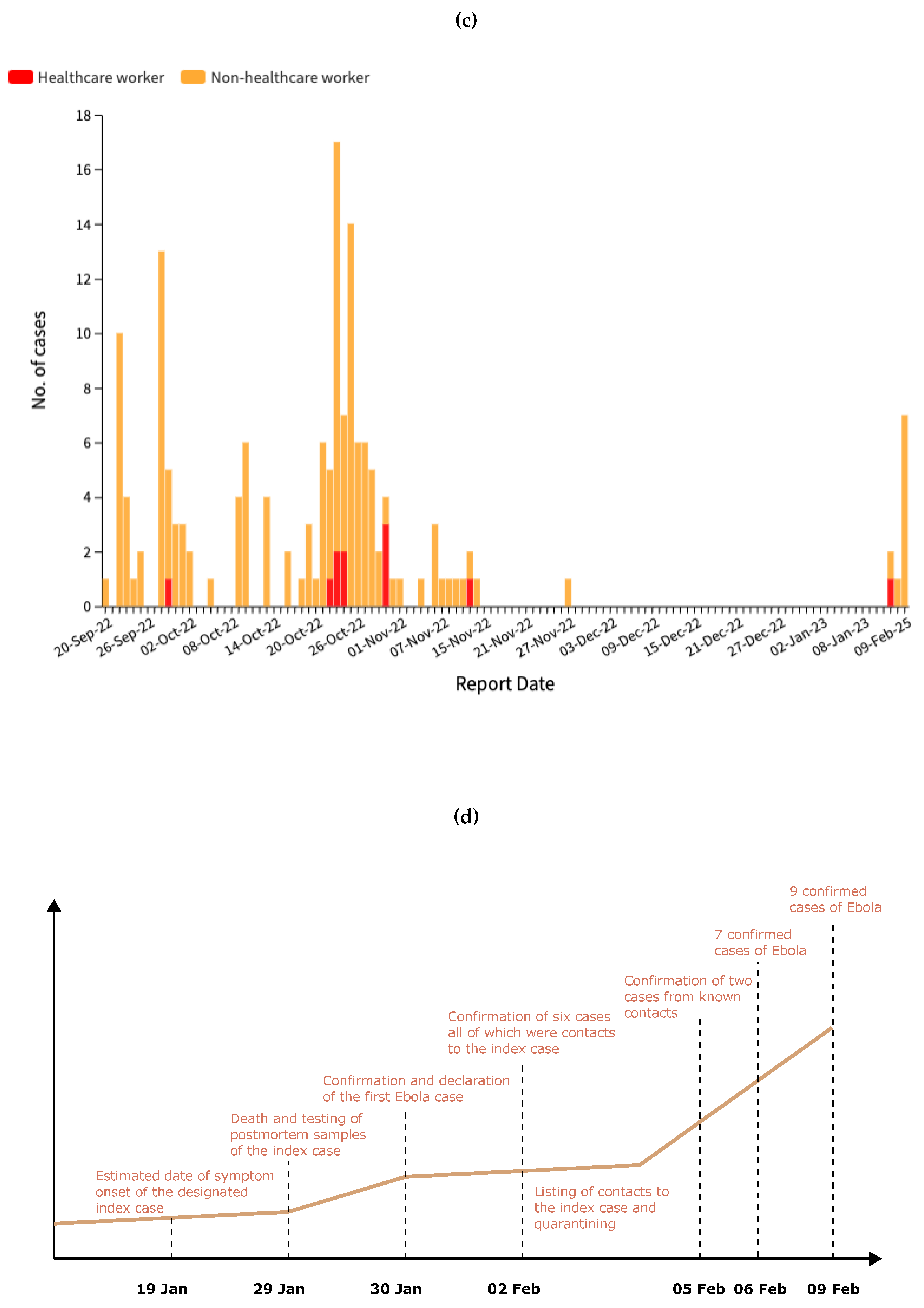

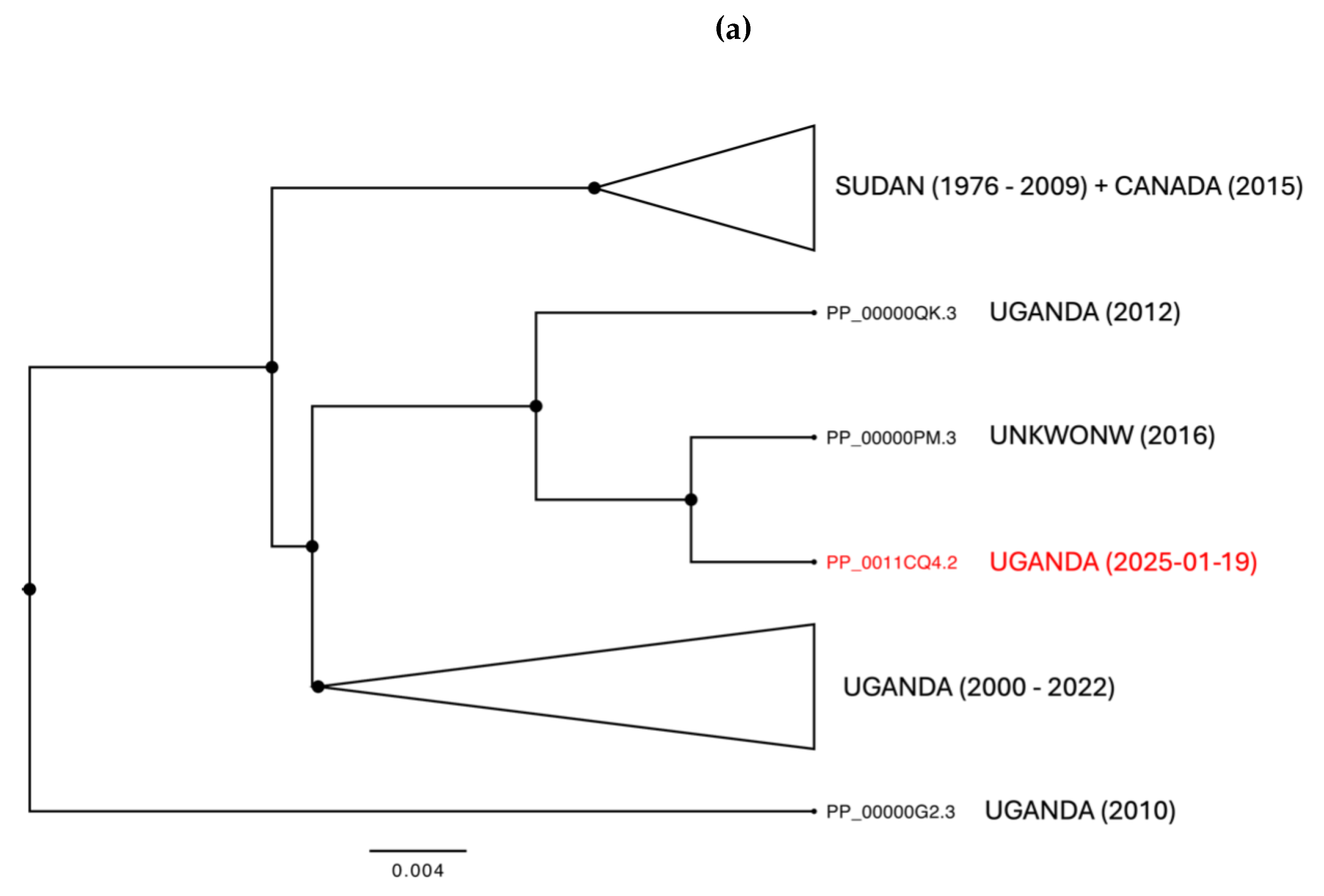

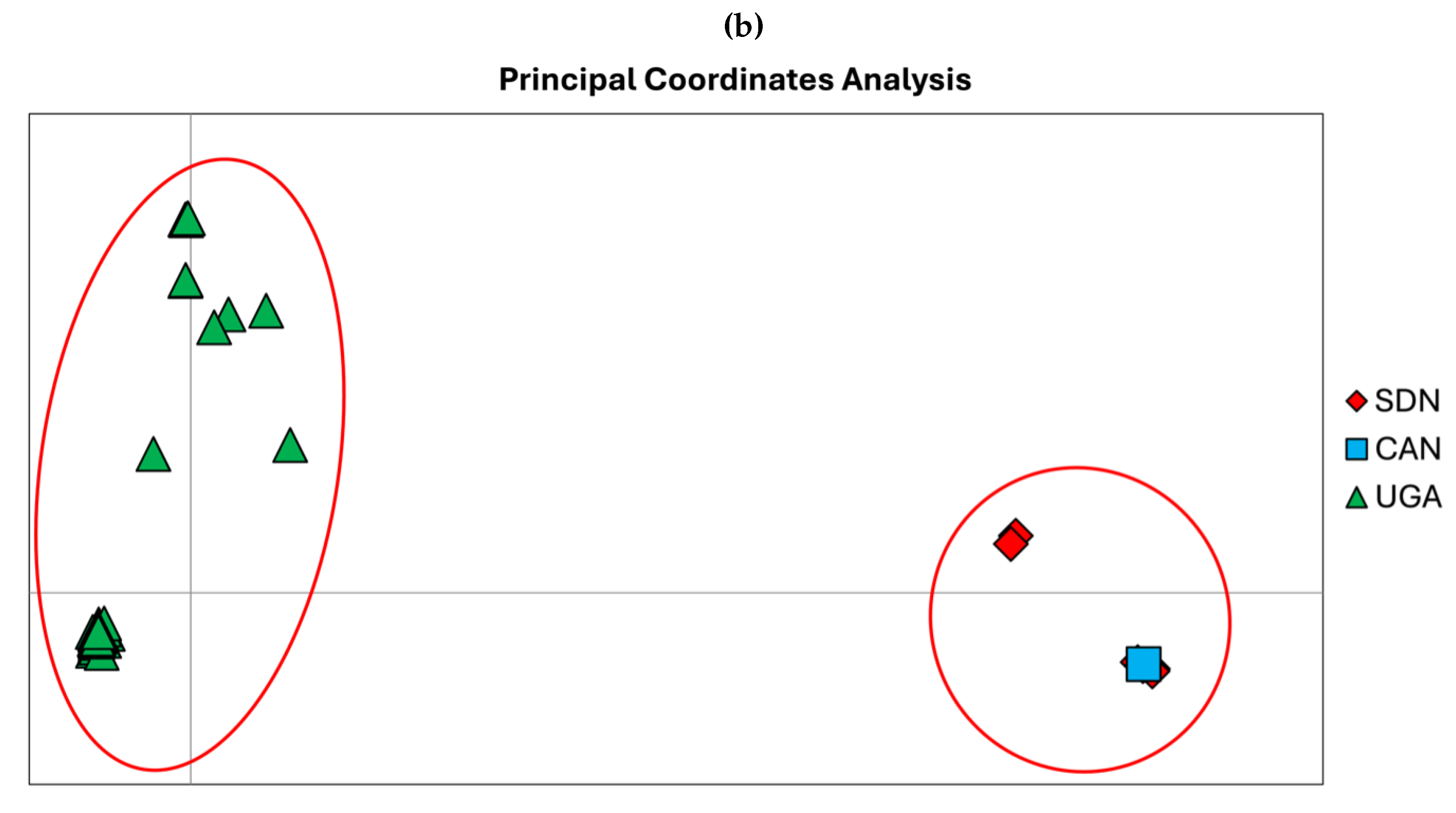

3.1.1. Phylogenomic Analysis

Phylogenomic analyses identify two main genetic clusters representing the genetic variability of Sudan and Uganda, respectively (

Figure 2a). These clusters reflect genetic patterns rather than being exclusive to a specific geographic area. The Sudanese cluster includes samples collected between 1976 and 2009, along with a geographical and temporal outlier from Canada, isolated in 2015 (PP_00000TD.3). In contrast, the Ugandan cluster is divided into two groups: one more recent, composed of isolates collected between 2000 and 2022, and another consisting of three strains isolated in 2012, 2016, and one from the current outbreak, collected on 2025-01-19. The geographical structure and the genetic differentiation shaping the two main clusters has been confirmed by PCoA analyses, which explain a cumulative variability of 92.97% across the three main axes (Axis 1: 43.85%, Axis 2: 21.22%, Axis 3: 18.89%) (

Figure 2b). The genetic differentiation between the two main clusters amounts to 0.055, between the two Ugandan groups to 0.010, and within the largest Ugandan group to 0.07. The evolutionary rate, estimated using a subset of samples with complete collection dates, is 3 × 10

−5 (95% HPD CI: 1.2308 × 10

−5 - 4.3042 × 10

−5).

Figure 2.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. All nodes are fully supported for Posterior Probabilities (PP). The terminal labeled in red font represent the only one available for the new current outbreak in Uganda. (b) Principal coordinate analysis of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. The cumulative variability explained by the first three axes amounts to 92.97% (Axis1: 43.85%, Axis2: 21.22%, Axis3: 18.89%) The groups were set a priori in accordance with the sampling locality.

Figure 2.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. All nodes are fully supported for Posterior Probabilities (PP). The terminal labeled in red font represent the only one available for the new current outbreak in Uganda. (b) Principal coordinate analysis of all genomes of Ebola Sudan. The cumulative variability explained by the first three axes amounts to 92.97% (Axis1: 43.85%, Axis2: 21.22%, Axis3: 18.89%) The groups were set a priori in accordance with the sampling locality.

4. Discussion

The epidemiological characterization of the SUDV outbreaks in Uganda highlights significant variations in transmission dynamics, case fatality rates, and geographic spread over the past two decades. Through our research team’s commitment to building and maintaining a comprehensive open-access database, we have been able to track and analyze outbreak data in real-time, providing crucial insights into the evolution of these epidemics.

Our analysis of previous outbreaks, particularly those in 2022, reveals a recurrent pattern of localized transmission with occasional spillover into urban centers, necessitating robust surveillance and early response mechanisms. The latest outbreak in 2025, with an index case identified in Kampala, underscores the persistent risk of viral re-emergence and the challenges in controlling transmission in densely populated areas. CFRs observed in different outbreaks have varied substantially, from 52.7% in the 2000 outbreak to 33.5% in the 2022 outbreak. These changes can be attributed to improvements in clinical management, more effective detection and reporting mechanisms, and increased public health preparedness. However, despite these advances, the ongoing epidemic in 2025 raises concerns about the effectiveness of existing containment strategies, especially in the context of urban transmission. The presence of cases in multiple districts and the identification of health workers among those infected suggest that nosocomial transmission remains a critical factor in the spread of SUDV.

The role of human mobility in epidemic dynamics is particularly evident in the 2025 epidemic. The index case was a 32-year-old nurse, a resident of Wakiso district, who developed symptoms on January 19, 2025, and died on January 29 in Kampala. During the symptomatic period, he sought care from a traditional healer in Mbale district and visited three different health facilities: one in Wakiso district, one in Mbale district, and one in Kampala. The source of the Sudan virus exposure is still under investigation [

21]. This underscores the need for improved case identification and contact tracing, particularly among frontline workers who are at greater risk of exposure. The rapid identification of more than 230 contacts, including symptomatic individuals who required isolation, suggests that Uganda’s public health system has made progress in responding to the outbreak. However, the delays in case detection observed in the early phase of this outbreak highlight the need to strengthen real-time surveillance and diagnostic capabilities.

Comparing the epidemiological profiles of these outbreaks, it is clear that although SUDV has remained largely confined to specific geographic regions, the risk of wider spread remains high. Urbanization, increased connectivity between districts and health care-seeking behaviors contribute to the complexity of containing outbreaks. In addition, the involvement of traditional healers, as seen in the 2025 outbreak, presents an additional challenge to ensure timely medical intervention and prevent further spread.

Another key finding of this study is the importance of integrating genomic surveillance with epidemiological surveys. While epidemiological data provide insights into transmission dynamics, genomic analyses are critical to understanding viral evolution and potential changes in virulence or transmissibility. The combination of these approaches will improve the ability to predict and mitigate future outbreaks. The phylogenomic analyses conducted in this study reveal a clear genetic structure within the SUDV lineage, distinguishing two main clusters representing samples from Sudan and Uganda. These clusters are indicative of genetic divergence but are not strictly confined to specific geographic regions, suggesting ongoing viral evolution and potential interregional transmission events. The Sudanese cluster encompasses isolates spanning over three decades (1976–2009) and includes a notable geographical and temporal outlier from Canada, isolated in 2015. The presence of this outlier may indicate an introduction event into a non-endemic region, possibly linked to travel or laboratory exposure. In contrast, the Ugandan cluster displays a more complex structure, divided into two subgroups: one comprising more recent isolates (2000–2022) and another containing three strains from 2012, 2016, and the most recent sample from the current outbreak (2025-01-19). This split suggests distinct transmission chains or evolutionary trajectories within Uganda, potentially shaped by localized outbreaks and varying transmission dynamics. The genetic differentiation between the Sudanese and Ugandan clusters is quantified at 0.055, suggesting a moderate degree of divergence, potentially resulting from geographical separation and independent evolutionary pressures. Within Uganda, the differentiation between the two subgroups is lower (0.010), implying a more recent common ancestry or ongoing genetic exchange. Notably, the largest Ugandan group exhibits an internal differentiation of 0.07, indicating a significant level of genetic diversity, possibly due to recurrent introductions or mutations accumulating over time. The differentiation can suggest that the Sudanese and Ugandan lineages have undergone distinct evolutionary paths, with the Sudanese lineage showing a more established divergence over time, while the Ugandan strains display signs of more recent diversification. The higher differentiation within the largest Ugandan group may indicate the presence of multiple circulating lineages within the country, which could have implications for viral transmission and immune escape. Such genetic distances align with previous studies on filoviruses, where geographic and host factors contribute to evolutionary dynamics. The relatively lower differentiation between Ugandan subgroups suggests a more recent divergence, potentially due to localized outbreaks or transmission bottlenecks. The estimated evolutionary rate of Sudan virus (i.e, 3 × 10−5 substitutions per site per year) is consistent with previous estimates for filoviruses and suggests a relatively stable molecular clock. However, the observed genetic differentiation and clustering patterns highlight the potential for viral adaptation and evolution, which could impact outbreak dynamics, transmission efficiency, and vaccine or therapeutic effectiveness. As a consequence, the spread of the virus that is not uniform, with some areas serving as epicenters of infection and others recording only sporadic but still significant cases to understand the mechanisms of propagation. A central issue is the link between the mobility of individuals and the ability of the virus to spread beyond initially affected areas. Travel for health or personal reasons is a crucial vector in transmission, highlighting the need for targeted strategies for contact tracing and early containment. In addition, the recurrence of outbreaks raises questions about the persistence of the virus in the environment or potential animal reservoirs, suggesting the need for an integrated approach that combines human and veterinary surveillance. Although response measures have improved over time, critical issues persist related to delays in initial diagnosis and management of infections in hospital settings, factors that can amplify nosocomial transmission and complicate outbreak control. Beyond its impact in Africa, we emphasize that Ebola is not solely a regional concern but a potential global threat. With increasing international travel and human mobility, the risk of spillover events beyond endemic regions has grown, underscoring the need for robust global surveillance, rapid response mechanisms, and coordinated international efforts to prevent future outbreaks.

5. Conclusion

These findings underscore the importance of continuous genomic surveillance to monitor the evolutionary trajectory of Sudan virus. The identification of distinct genetic clusters and the presence of an outlier in a non-endemic region emphasize the need for robust epidemiological investigations to trace transmission pathways and assess potential spillover events. Future studies should focus on whole-genome sequencing of newly emerging strains, integration of epidemiological data, and assessment of phenotypic changes associated with genetic mutations to better understand the implications of viral evolution on public health interventions. Furthermore, sustained investment in epidemic preparedness is crucial, including community involvement, training of healthcare workers, and expansion of rapid diagnostic capabilities. Future outbreak response strategies must prioritize early detection, cross-border coordination, and the development of targeted interventions to mitigate the impact of SUDV in Uganda and elsewhere. The recurrent nature of SUDV outbreaks suggests that continuous surveillance and adaptive public health measures are essential to prevent large-scale epidemics and minimize the burden of this deadly virus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., M.C. and F.S.; data curation, F.B.; formal analysis, F.B. and F.S.; supervision, M.C.; validation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B., M.C. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, F.B., M.C. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Letafati, A.; Ardekani, O.S.; Karami, H.; Soleimani, M. Ebola virus disease: A narrative review. Microbial Pathogenesis 2023, 181, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grard, G.; Biek, R.; Muyembe Tamfum, J.J.; Fair, J.; Wolfe, N.; Formenty, P.; Paweska, J.; Leroy, E. Emergence of divergent Zaire ebola virus strains in Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2007 and 2008. The Journal of infectious diseases 2011, 204, S776–S784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kainulainen, M.H.; Harmon, J.R.; Whitesell, A.N.; Bergeron, É.; Karaaslan, E.; Cossaboom, C.M.; Malenfant, J.H.; Kofman, A.; Montgomery, J.M.; Choi, M.J.; others. Recombinant Sudan virus and evaluation of humoral cross-reactivity between Ebola and Sudan virus glycoproteins after infection or rVSV-ΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccination. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2023, 12, 2265660. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.A.; Towner, J.S.; Sealy, T.K.; McMullan, L.K.; Khristova, M.L.; Burt, F.J.; Swanepoel, R.; Rollin, P.E.; Nichol, S.T. Molecular evolution of viruses of the family Filoviridae based on 97 whole-genome sequences. Journal of virology 2013, 87, 2608–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Notes from the Field: Outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease Caused by Sudan ebolavirus — Uganda, August–October 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7145a5.htm?utmsource=chatgpt.com (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Leroy, E.M.; Kumulungui, B.; Pourrut, X.; Rouquet, P.; Hassanin, A.; Yaba, P.; Délicat, A.; Paweska, J.T.; Gonzalez, J.P.; Swanepoel, R. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature 2005, 438, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.K.; Dhama, K.; Malik, Y.S.; Ramakrishnan, M.A.; Karthik, K.; Khandia, R.; Tiwari, R.; Munjal, A.; Saminathan, M.; Sachan, S.; others. Ebola virus–epidemiology, diagnosis, and control: threat to humans, lessons learnt, and preparedness plans–an update on its 40 year’s journey. Veterinary Quarterly 2017, 37, 98–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subissi, L.; Keita, M.; Mesfin, S.; Rezza, G.; Diallo, B.; Van Gucht, S.; Musa, E.O.; Yoti, Z.; Keita, S.; Djingarey, M.H.; others. Ebola virus transmission caused by persistently infected survivors of the 2014–2016 outbreak in West Africa. The Journal of infectious diseases 2018, 218, S287–S291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Ebola; Outbreak History. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ebola/outbreaks/index.html (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- World Health Organization (1 February 2025). Disease Outbreak News; Sudan virus disease in Uganda. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON555 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Branda, F.; Mahal, A.; Maruotti, A.; Pierini, M.; Mazzoli, S. The challenges of open data for future epidemic preparedness: The experience of the 2022 Ebolavirus outbreak in Uganda. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular biology and evolution 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; Team, U. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC evolutionary biology 2007, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kass, R.E.; Raftery, A.E. Bayes factors. Journal of the american statistical association 1995, 90, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Systematic biology 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular ecology notes 2006, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E.; Claude, J.; Strimmer, K. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 289–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (1 February 2025). Disease Outbreak News; Sudan virus disease in Uganda. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON555 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- World Health Organization (21 February 2025). Disease Outbreak News; Sudan virus disease in Uganda. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON556 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- CDC. Ebola Outbreak Caused by Sudan virus in Uganda.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).