1. Introduction

Monkeypox virus (MPXV) is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the family Poxviridae, subfamily

Chordopoxvirinae, and genus

Orthopoxvirus. Variola virus (the causative agent of smallpox), Vaccinia virus (used in smallpox vaccines), and Cowpox virus are some other members of the genus [

1]. MPXV was first detected in 1958 in captive research monkeys from Copenhagen, Denmark, and subsequently as a human pathogen when the disease was detected in a 9-month-old child from the DRC in 1970 [

2]. Mpox infections were initially confined to Central and West Africa, largely due to zoonotic spillover incidents with limited human-to-human transmission. But in 2022, the epidemiological profile had changed, spread across the globe, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare mpox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) (PHEIC) [

3,

4].

MPXV has a large, linear, double-stranded DNA genome of approximately 190 kb, encoding over 190 proteins. The genome consists of a conserved central domain (~ 32kb-138kb) with fundamental functions of encoding genes responsible for viral replication, essential enzymes, and structural proteins. The conserved region is flanked by variable terminal regions that contain inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), coding for the most part for host-interaction factors [

5]. The long terminal regions include genes associated with immune evasion, host specificity, and virulence (

Figure S2). ORFs are named according to the orthopoxvirus gene nomenclature (e.g., OPG001) [

6] (

Figure S1). Significant ORFs encode DNA polymerase, RNA polymerase subunits, envelope proteins, and virulence-associated proteins such as complement regulatory proteins [

1]. Comparative genomic studies have detected genetic distinctions between Clade I and Clade II MPXV, particularly in immune modulating genes, that may explain virulence differences [

7].

Mpox is classified into two principal clades designated as Clade I (Central African) and Clade II (West African), with further subdivisions into Clades Ia, Ib, IIa, and IIb respectively [

7]. Clade I is historically associated with higher morbidity and mortality, disproportionately affecting children and immunocompromised individuals, whereas Clade II has been implicated in the recent global outbreaks, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM) [

8]. Mpox however remains endemic in the sub-Saharan countries including DRC, Central African Republic, Cameroon, and Nigeria, with reported cases in Ghana [

9]. The natural reservoir of MPXV remains unknown, although zoonotic transmission is suspected to be caused by African rodents and non-human primates [

10].

On a global scale, multiple mpox outbreaks have been reported in over 130 countries by April 2025, with sustained human-to-human transmission [

11]. The 2022–2024 outbreaks in Europe, North America, and Asia also demonstrated novel transmission dynamics, including sexual transmission networks and asymptomatic carriers [

11,

12,

13]. While Clade II remains dominant in these outbreaks, genomic sequencing has revealed mutations associated with increased transmissibility [

14].

Several public health efforts have been coordinated by WHO to curb the spread of mpox, these include targeted vaccination strategies, enhanced surveillance, and support for rapid diagnostic capacities. However, vaccine access remains inequitable, particularly in endemic regions of Africa. The United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, among others, have been successful in rolling out targeted vaccination programs primarily to high-risk groups while sub-Saharan Africa continues to trail behind in vaccine distribution and epidemic control [

15]. By August 2024, over 20,000 suspected cases and 500 deaths had been reported in the DRC [

16], hence emphasizing the important need for increased genomic surveillance, equitable vaccine distribution, and international collaboration to mitigate mpox outbreaks.

Given the high mpox burden in both endemic and non-endemic regions, it is crucial to elucidate the genetic diversity and evolutionary processes of MPXV, which this study aims to investigate by analyzing MPXV strains in sub-Saharan Africa between 2022 and 2024 providing insights that are valuable for surveillance and management of outbreaks.

2. Materials and Methods

Sequence Retrieval and Curation

Complete genome sequences of the Mpox virus (MPXV) were retrieved from GISAID EpiPox (400 sequences) (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data)

(https://gisaid.org/) between January 1, 2022, and December 31, 2024, on March 4th, 2025. Accession numbers were selected from 13 African countries with high Mpox prevalence throughout this time interval. Sequences underwent several curation processes for data quality. Duplicate sequences were eliminated. Sequences of sizes ranging from 190–205 kb were kept ensuring completeness and consistency. Sequences containing more than 10% ambiguous nucleotides (Ns) were excluded to ensure high-confidence data. Sequence preprocessing was carried out using Biopython scripts (Python 3.9) [

17]. After curation, 270 sequences were kept for further analysis including DRC (n=167), Nigeria (n=38), Central African Republic (n=14), Burundi (n=9), South Africa (n=9), Ghana (n=7), Uganda (n=7), Cote d'Ivoire (n=5), Cameroon (n=4), Liberia (n=5), Benin (n=2), Kenya (n=2), and Congo (n=1).

Sequence Alignment

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) was performed with MAFFT v7.526 [

18] using the auto strategy to optimize speed with an assurance of accuracy. TrimAl v1.4. rev15 (build 2013-12-17) [

19] was used to filter the alignment, applying a 0.05 gap threshold to remove poorly aligned regions. The quality of the alignment was visually inspected, and manual adjustments performed with AliView v1.26[

20].

Phylogenetic Analysis

A maximum likelihood (ML) tree was constructed using IQ-TREE v2.3.6 [

21]. The best-fitting nucleotide substitution model, K3Pu+F+I+R3 was selected using Model Finder [

22] with Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values for the best fit to the data. For tree robustness, 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates were performed [

23]. The 2016 sequence (EPI_ISL_18689512) was used as an outgroup to root the phylogenetic tree and for evolutionary context.

Tree Visualization and Annotation

The resultant phylogenetic tree was visualized and annotated using iTOL v7.1[

24].

Mutational Analysis

Mutational analysis was performed by aligning the reference sequence NC_063383.1 (MPXV, 2018) with 12 representative mutant sequences for each lineage and clades using BWA for indexing and alignment v0.7.17-r1188 [

25]. The aligned sequences were converted from SAM to BAM format, sorted, and indexed. Variant calling was carried out with BCF tools v1.19 [

26], followed by variant annotation using snpEff v5.2e [

27,

28]. A custom Mpox database was created to facilitate the annotation process, and a standard genetic code was set. A python script was developed to rapidly screen APOBEC3 mutation profiles (

File_S3).

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of Mpox Virus in Sub-Saharan Africa (2022–2024)

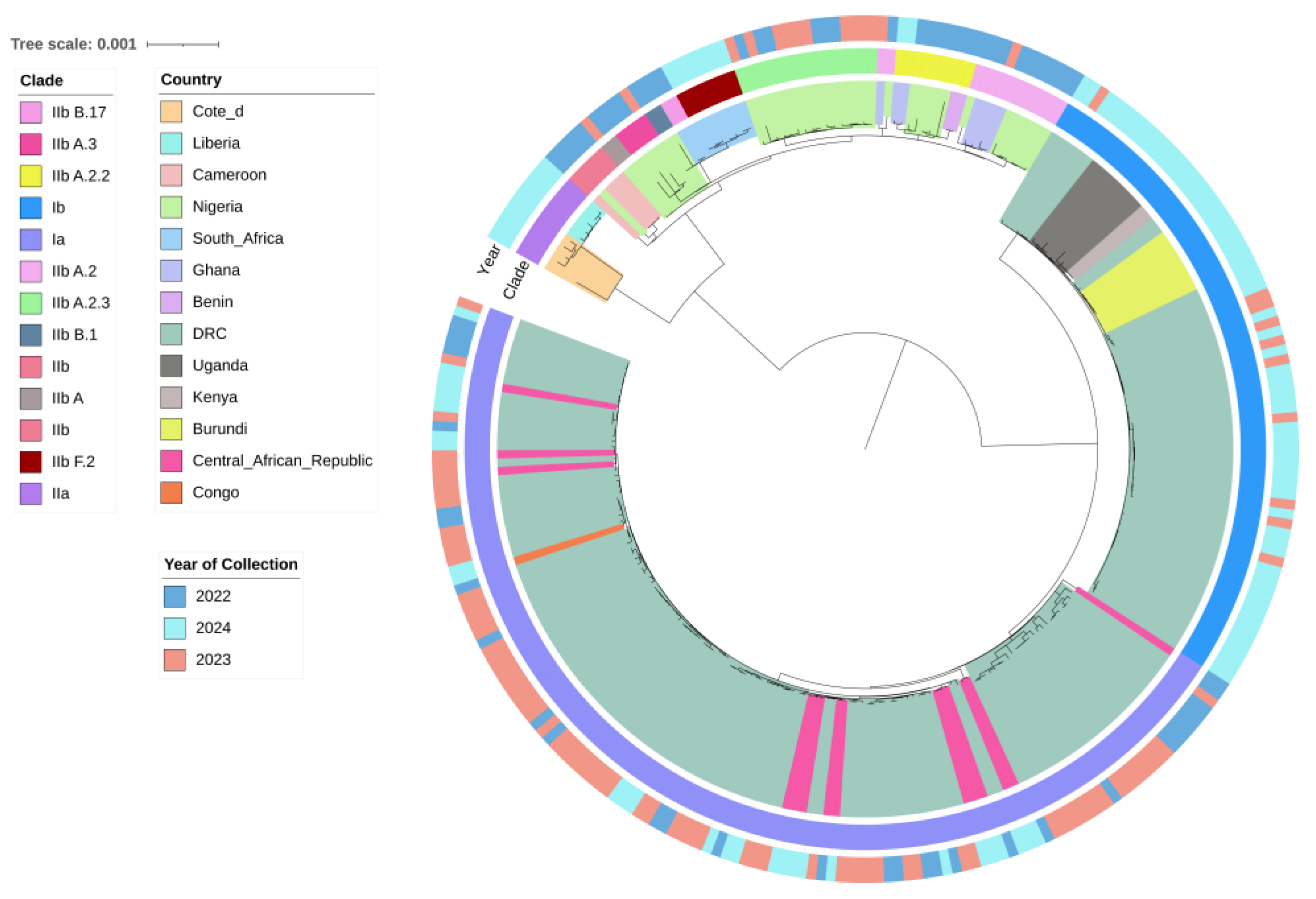

Phylogenetic analysis of 270 curated Mpox virus (MPXV) sequences from Sub-Saharan Africa identified two major clades that is Clade I (Ia, Ib) and Clade II (IIa, IIb). The phylogenetic tree topology revealed distinct evolutionary patterns (

Figure 2). Clade I (Ia and Ib) was found predominantly in regions like the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Uganda, Burundi, Central African Republic (CAR), Kenya, and the Republic of Congo (

Figure 2). In 2023–2024, Clade Ib became dominant (

Figure 2). Clade II was widely distributed across West and Southern Africa, with Clade IIb in countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, and Cameroon, and Clade IIa in Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire (

Figure 2). Clade IIb exhibited ongoing circulation since 2022 and has since diverged into several sub-lineages i.e. A, A.2, A.2.2, A.2.3, A.3, B.1, B.17 and F.2 (according to GISAID’s classification) (

Figure 2). Refer to the supplementary materials section for metadata file (

Table_S1) used for analysis and also the phylogenetic analysis files (

Figure_S4).

3.2. Mutational Analysis of Mpox Virus in Sub-Saharan Africa (2022–2024)

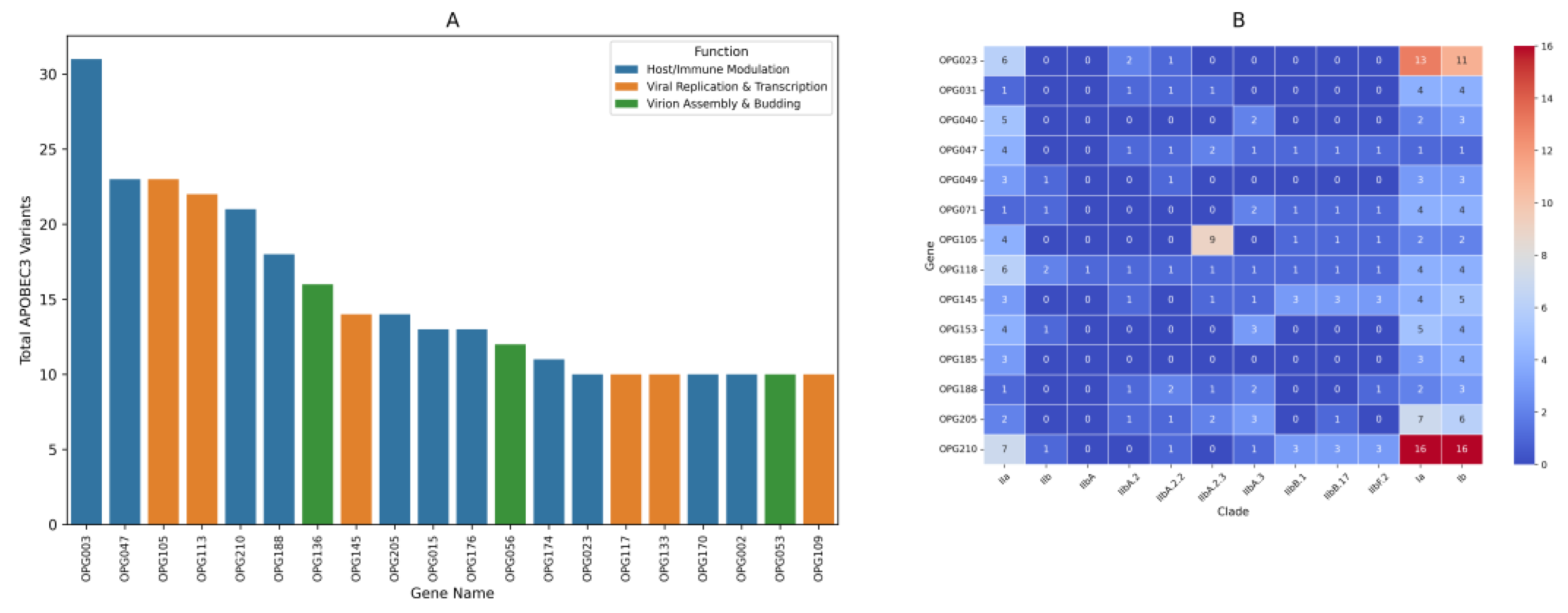

Mutational analysis of Mpox virus sequences identified notable nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions when compared to the reference genome NC_063383.1 (MPXV, 2018). A closer examination of the consensus mutated genes revealed the top ten most frequently mutated genes across the clades. OPG210 gene had the highest mutation count, followed by OPG023, OPG118, OPG145, OPG205, OPG105, OPG153, OPG071, OPG047 and OPG188(

Figure 3B).

Mutations predominantly impacted genes linked to immune modulation and viral replication. In depth functional analysis revealed specific consensus amino acid substitutions associated with some of these genes. OPG205 gene, for example, related to immune evasion, showed substitutions such as R689C, W169R, and C349Y. OPG023, related to virus-host interaction, showed K637E, L602I, and T488A. OPG210, which presumably relates to immune evasion, showed D209N, P722S, and M1741I. Similarly, OPG118, involved in regulation of early gene expression, showed substitutions such as K606E, N413S, and K256R. OPG105, which is also involved in viral transcription, exhibited substitutions such as S734L, V113G, and I1070V, while eventually OPG145, which is related to DNA helicase activity, expressed substitutions such as E62K, R243Q, and E435K(

File_S2).

Clade specific findings revealed distinct patterns of mutations; Clade I showed the highest number of substitutions, particularly OPG023, OPG210, and OPG205. Lineage B.1 contained a higher number of substitutions in OPG210 than Lineage A. Lineage IIbA.2.3 included the highest number of substitutions in OPG105 than NC_063383.1 (MPXV, 2018) (

Figure 3B).

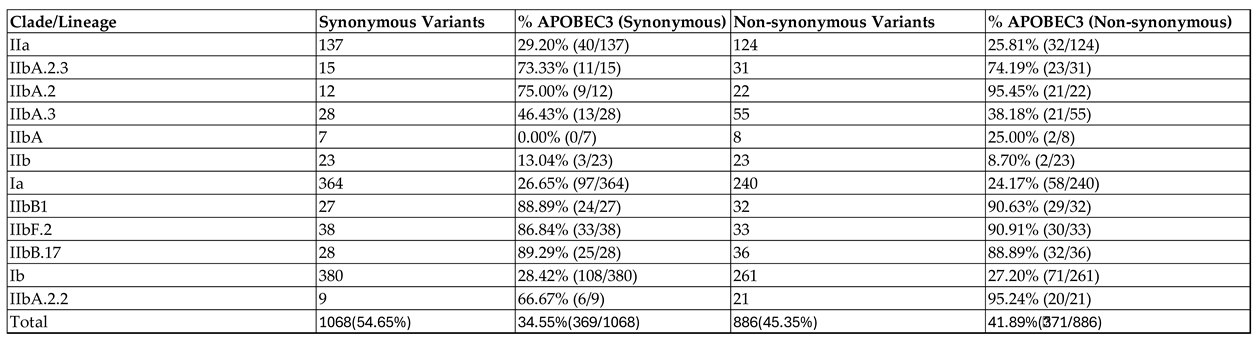

Analysis of mutational patterns identified non-synonymous variants, which were 45.35% of the mutations, and synonymous variants, which were 54.65% of the mutations. 34.55% of synonymous variants followed an APOBEC3 pattern while 41.89% of nonsynonymous variants followed an APOBEC3-like mutational pattern (

Table 1).

Clade IIb had the highest proportion of APOBEC3 variants especially lineage B.1 and its sub lineages (B.17 andF.2) having the highest average proportion i.e. 88.34% and 90.14% of APOBEC3 variants in synonymous and non-synonymous mutations respectively. Consequently, Clade I generally had the lowest number of APOBEC3 variants with an average of 27.54% and 25.69% in synonymous and non-synonymous variants respectively (

Table 1).

Genes targeted by APOBEC3 variants dominated those responsible for host immune modulation and viral replication and transcription (

Figure 3A).For further details refer to the supplementary materials section for mutational analysis files (

File_S2), a python code used in filtering APOBEC3 variants (

File_S3) and the resultant APOBEC3 variants excel files for each of the representative sequences for each clade and lineages (

Figure_S4).

4. Discussion

Phylogenetic Analysis: Evolution of Clades and Sub-Clades

The phylogenetic tree constructed from MPXV isolates in Sub-Saharan Africa confirms the presence of both Clade I (subclades Ia and Ib) and Clade II (subclades IIa and IIb). The findings are in line with previous studies [

1,

29,

30,

31,

32], which have documented the evolving genetic profile of MPXV. Interestingly, Isidro et al. [

30] (p. 1) reported that the transition from Lineages A.1/A.1.1 to B.1 was characterized by a long divergent branch that indicates accelerated microevolution. This is also supported by our phylogenetic tree, which also indicates the same branching pattern (

Figure 2). In addition, we observed that there were more substitutions in OPG210, an immune evasion gene, for Lineage B.1 than for Lineage A (

Figure 3B). This selection of mutations could be additional evidence for divergent and adaptive evolution in the lineage.

The prevalence of Clade I in Central Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and adjacent regions is consistent with previous reports [

14]. The close genetic affiliations of Clade Ib Kenyan, Burundian, and Ugandan strains with DRC strains suggest that transborder movement is possibly driving MPXV spread in Central and East Africa [

33] (

Figure 2). However, the geographic distribution of Clade I remains speculative, and additional comprehensive epidemiological data are necessary to determine if indeed persistent transmission is occurring in these regions.

Mutation Patterns : APOBEC3, Synonymous and Non-Synonymous Variants

A greater proportion of the mutations in Clade IIb particularly B.1 lineage follows an APOBEC3-like signature, consistent with previous findings [

1,

29] (Table.1). The APOBEC3 family is known as a cytidine deaminase known to play important functions in innate anti-viral immunity [

34] hence exerting evolutionary pressure on the viral genome, resulting in GA>AA, GG>AA and TC>TT transitions that may influence viral fitness [

1]. Our results show that these APOBEC3-induced mutations are predominantly found in immune-modulatory genes like OPG210, OPG047, and OPG003(

Figure 3A), suggesting an ongoing host-virus interaction that may drive viral adaptation to immune pressures.

Interestingly, we observed a rise in non-APOBEC3 mutations in recent isolations, especially in Clade I, a shift from the previous studies that indicated lower numbers of non-APOBEC3 mutations present mostly in Clade II lineages [

1,

14] (

Table 1). There have been recent reports of mutations in the MPXV that have atypical APOBEC3-mediated signatures, which could reflect other mutational mechanisms at play [

35], hence possibly indicating an evolutionary escape from host mutagenic pressures. This shift aligns with observations within other viral systems, whereby avoiding APOBEC3 editing pressures is advantageous for greater genetic stability and long-term viral survival. Martinez et al. [

36] (p. 7) for example noted a rise in non-APOBEC3 mutations in human gamma-herpesviruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus, reflecting an adaptive process that minimizes the impact of APOBEC3 editing. Furthermore, research on HIV-1 [

37] indicated that the virus gains both expected and unexpected mutations, as well as those not linked to APOBEC3 activity, confirming its ability to adapt under selective pressures.

The distribution of synonymous and non-synonymous mutations offers insight into MPXV evolution. We observed that 54.65% of mutations were synonymous, while 45.35% were non-synonymous (

Table 1). Although synonymous mutations do not alter amino acid sequences, they can influence codon usage bias, RNA structure, and translation efficiency [

38,

39]. MPXV codon use patterns, plus natural selection and mutational stress, can also have the possibility of affecting viral adaptation. Noteworthy, codon usage bias has been reported to differ amongst more virulent Central African and less virulent West African strains hence indicating a possibility of association with pathogenicity [

40].

Conversely, non-synonymous mutations often alter viral proteins, hence impacting replication, immune evasion, and transmission. The rise in non-synonymous variants in Clade IIb’s B.1 isolates relative to NC_063383.1 (MPXV, 2018)(

Figure 3B) underscores selective pressures on MPXV [

28,

41]. Recent studies have reported accelerated protein sequence changes in 2022 outbreak strains [

30], alongside a declining codon adaptation index (CAI), which may possibly suggest a shift toward non-preferred codons and potential changes in viral fitness and pathogenicity [

28].

Clade-Specific Mutations: Implications for Transmission and Adaptation

Several key mutations in specific viral genes might be linked to clade-specific differences in transmission and disease progression. For example, Clade I, which is currently more transmissible in sub-Saharan Africa, exhibits a higher frequency of mutations in immune related genes compared to NC_063383.1 (MPXV, 2018) (

Figure 3B). These mutations, which include changes in the OPG 210, OPG205 and OPG023 genes, may contribute to an enhanced ability of Clade I to evade immune surveillance and replicate more efficiently [

32,

42]. This mirrors findings in other poxviruses where mutations in immune-modulatory genes were associated with more successful replication and spread [

43].

The high mutation rate observed in OPG105 within Clade IIb A.2.3 compared to NC_063383.1 (MPXV, 2018) is particularly noteworthy (

Figure 3B). As a key gene involved in viral transcription, its increased mutational burden in this lineage suggests a potential selective advantage in replication and immune evasion. Studies have reported that mutations in OPG105 may alter viral gene regulation, potentially enhancing persistence and transmission [

32,

42,

44]. These findings underscore the role of OPG105 in MPXV adaptation and its potential impact on viral fitness.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the dynamic nature of MPXV evolution in Sub-Saharan Africa. The continued diversification of Clade IIb, along with the emergence of distinct sublineages, highlights the virus's ability to adapt to different regions and ecological contexts. Mutational patterns, particularly those driven by APOBEC3 and the rise of non-synonymous mutations, suggest ongoing viral adaptation to immune pressures and transmission dynamics. The findings also raise important questions about the role of specific mutations in transmission and pathogenicity, particularly in relation to the more transmissible Clade I and the genetically divergent Clade IIb.Future research should focus on further elucidating the functional impact of these mutations, particularly those in immune-related and transcription-regulatory genes, to better understand how MPXV is evolving in response to both host immune defenses and antiviral interventions. Sustained genomic surveillance and epidemiological studies will be essential in tracking these changes and informing effective public health strategies to mitigate the spread of MPXV across regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.Org.

- ○

S1: Schematic representation of the MPXV genome architecture, indicating ORF, CDS, and miscellaneous regions, generated using Proksee.

- ○

S2: Genomic functionality, color-coded based on functionality, generated using Python's Matplotlib.

File S2: Mutational analysis files (zip file containing detailed analysis).

File S3: APOBEC3 filter, Python script used for variant filtering.

File S4: Phylogenetic analysis files (zip file containing the phylogenetic analysis data).

File S5: APOBEC3 variants data (zip file with variants).

Table S1: Metadata used for sequence analysis (Excel file).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Millicent Ochieng; Data curation, Millicent Ochieng and Josiah Kuja³; Formal analysis, Millicent Ochieng; Investigation, Millicent Ochieng; Methodology, Millicent Ochieng; Project administration, Dorcus Omoga; Resources, Carolyne Nasimiyu and Daniel Kiboi; Software, Millicent Ochieng; Supervision, Josiah Kuja³, Carolyne Nasimiyu, Eric Osoro, Dorcus Omoga and Daniel Kiboi; Validation, Millicent Ochieng, Josiah Kuja³ and Eric Osoro; Visualization, Millicent Ochieng; Writing – original draft, Millicent Ochieng; Writing – review & editing, Josiah Kuja³ and Carolyne Nasimiyu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available in the supplementary section of this article and can be accessed through the MDPI repository link

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) would like to acknowledge Washington State University for generously covering the publication costs associated with this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Term |

| MPXV |

Monkeypox Virus |

| APOBEC3 |

Apolipoprotein B mRNA Editing Enzyme Catalytic Subunit 3 |

| OPG |

Orthopoxvirus Gene |

| DRC |

Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| BIC |

Bayesian Information Criterion |

| CAR |

Central African Republic |

| ML |

Maximum Likelihood |

| MSA |

Multiple Sequence Alignment |

| MSM |

Men Who Have Sex with Men |

| PHEIC |

Public Health Emergency of International Concern |

| ITR |

Inverted terminal repeats |

References

- Alakunle, E.; Kolawole, D.; Diaz-Cánova, D.; Alele, F.; Adegboye, O.; Moens, U.; Okeke, M. I. A comprehensive review of monkeypox virus and mpox characteristics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, Article 1360586. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1360586.

- Martínez-Fernández, D. E.; Fernández-Quezada, D.; Casillas-Muñoz, F. A. G.; Carrillo-Ballesteros, F. J.; Ortega-Prieto, A. M.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J. M.; Regla-Nava, J. A. Human Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Overview of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention Strategies. Pathogens 2023, 12, 947. [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, V.; Paul, A.; Trivedi, V.; Bhatnagar, R.; Bhalsinge, R.; Jadhav, S. V. Global epidemiology, viral evolution, and public health responses: A systematic review on Mpox (1958–2024). J. Glob. Health 2025, 15, 04061. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern. WHO 2024, August 14. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern.

- Shchelkunov, S. N.; Totmenin, A. V.; Safronov, P. F.; Mikheev, M. V.; Gutorov, V. V.; Ryazankina, O. I.; Petrov, N. A.; Babkin, I. V.; Uvarova, E. A.; Sandakhchiev, L. S.; Sisler, J. R.; Esposito, J. J.; Damon, I. K.; Jahrling, P. B.; Moss, B. Analysis of the monkeypox virus genome. Virology 2002, 297, 172–194. [CrossRef]

- Senkevich, T. G.; Yutin, N.; Wolf, Y. I.; Koonin, E. V.; Moss, B. Ancient Gene Capture and Recent Gene Loss Shape the Evolution of Orthopoxvirus-Host Interaction Genes. mBio 2021, 12, e01495-21. [CrossRef]

- Happi, C.; Adetifa, I.; Mbala, P.; Njouom, R.; Nakoune, E.; Happi, A.; Ndodo, N.; Ayansola, O.; Mboowa, G.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R. A.; Roemer, C.; Hodcroft, E.; Tegally, H.; O’Toole, Á.; Rambaut, A.; Pybus, O.; Kraemer, M. U. G.; Wilkinson, E.; de Oliveira, T. Urgent need for a non-discriminatory and non-stigmatizing nomenclature for monkeypox virus. PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001769. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P. M.; Adesola, R. O.; Priyadarsini, S.; Singh, R.; Shaheen, M. N. F.; Ogundijo, O. A.; Gulumbe, B. H.; Lounis, M.; Samir, M.; Govindan, K.; Adebiyi, O. S.; Scott, G. Y.; Ahmadi, P.; Mahmoodi, V.; Chogan, H.; Gholami, S.; Shirazi, O.; Moghadam, S. K.; Jafari, N.; Tazerji, S. S. Unveiling the Global Surge of Mpox (Monkeypox): A comprehensive review of current evidence. Microbe 2024, 4, 100141. [CrossRef]

- Africa CDC. Outbreak report: Mpox situation in Africa. Africa CDC 2024, July 30. https://africacdc.org/disease-outbreak/mpox-situation-in-africa/.

- Khodakevich, L.; Szczeniowski, M.; Manbu-ma-Disu, Jezek, Z.; Marennikova, S.; Nakano, J.; Messinger, D. The role of squirrels in sustaining monkeypox virus transmission. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1987, 39, 115–122. PMID: 2820094.

- World Health Organization. (2025, April 1). Global Mpox trends. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/#8_Disclaimers.

- Satapathy, P.; Mohanty, P.; Manna, S.; Shamim, M. A.; Rao, P. P.; Aggarwal, A. K.; Khubchandani, J.; Mohanty, A.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Chattu, V. K.; Padhi, B. K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A. J.; Sah, R. Potentially Asymptomatic Infection of Monkeypox Virus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10(12), 2083. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, A. M.; Afzal, M.; Nannapaneni, P.; Leroy, M.; Andrianou, X.; Pires, J.; Funke, S.; Roman, C.; Reyes-Uruena, J.; Aberle, S.; Aristodimou, A.; Aspelund, G.; Bennet, K. F.; Bormane, A.; Caraglia, A.; Charles, H.; Chazelle, E.; Christova, I.; Cohen, O.; … Gossner, C. M. Continued Circulation of Mpox: An Epidemiological and Phylogenetic Assessment, European Region, 2023 to 2024. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29(27), 2400330. [CrossRef]

- Bunge, E. M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L. R.; Steffen, R. The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox—A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16(2), e0010141. [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D. B.; Wada, O. Z.; Fidelis, S. C.; Oluwole, O. S.; Alisi, C. S.; Orimabuyaku, N. F.; Clement David-Olawade, A. Strengthening Africa’s Response to Mpox (Monkeypox): Insights from Historical Outbreaks and the Present Global Spread. Science in One Health 2024, 3, 100085. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Kalonji, T.; Miller, T.; Van Den Bossche, T.; Krolicka, A.; Muhindo-Mavoko, H.; Mitashi, P.; Tahita, M. C.; Lood, R.; Pitkänen, T.; Maketa, V. Emergence and Global Spread of Mpox Clade Ib: Challenges and the Role of Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2025, jiaf006. [CrossRef]

- Cock, P. J. A.; Antao, T.; Chang, J. T.; Chapman, B. A.; Cox, C. J.; Dalke, A.; Friedberg, I.; Hamelryck, T.; Kauff, F.; Wilczynski, B.; de Hoon, M. J. L. Biopython: Freely Available Python Tools for Computational Molecular Biology and Bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25(11), 1422–1423. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform. Nucleic Acids Research 2002, 30(14), 3059–3066. [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J. M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A Tool for Automated Alignment Trimming in Large-Scale Phylogenetic Analyses. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009, 25(15), 1972–1973. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. AliView: A Fast and Lightweight Alignment Viewer and Editor for Large Datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30(22), 3276–3278. [CrossRef]

- Minh, B. Q.; Schmidt, H. A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M. D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2020, 37(5), 1530–1534. [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B. Q.; Wong, T. K. F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D. T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B. Q.; Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent Updates to the Phylogenetic Tree Display and Annotation Tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J. K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M. O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S. A.; Davies, R. M.; Li, H. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L. L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S. J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D. M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.-J.; Wu, C.; Tang, X.; Lu, R.; Hu, Y.; Tan, W.; Lu, J. Molecular Evolution of Protein Sequences and Codon Usage in Monkeypox Viruses. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2024, 22, 1. [CrossRef]

- Gigante, C. M.; Korber, B.; Seabolt, M. H.; Wilkins, K.; Davidson, W.; Rao, A. K.; Zhao, H.; Smith, T. G.; Hughes, C. M.; Minhaj, F.; Waltenburg, M. A.; Theiler, J.; Smole, S.; Gallagher, G. R.; Blythe, D.; Myers, R.; Schulte, J.; Stringer, J.; Lee, P.; … Li, Y. Multiple lineages of monkeypox virus detected in the United States, 2021–2022. Science 2022, 378, 560–565. [CrossRef]

- Isidro, J.; Borges, V.; Pinto, M.; Sobral, D.; Santos, J. D.; Nunes, A.; Mixão, V.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, D.; Duarte, S.; Vieira, L.; Borrego, M. J.; Núncio, S.; de Carvalho, I. L.; Pelerito, A.; Cordeiro, R.; Gomes, J. P. Phylogenomic characterization and signs of microevolution in the 2022 multi-country outbreak of monkeypox virus. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1569–1572. [CrossRef]

- Luna Niño, N.; Ramírez, A.; Muñoz, M.; Ballesteros, N.; Patiño, L.; Castañeda Garzon, S.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A.; Ramírez, J. Phylogenomic analysis of the monkeypox virus (MPXV) 2022 outbreak: Emergence of a novel viral lineage? Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 49, 102402. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shang, J.; Weng, S.; Aliyari, S. R.; Ji, C.; Cheng, G.; Wu, A. Genomic annotation and molecular evolution of monkeypox virus outbreak in 2022. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28036. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Bhattacharya, M.; Das, A.; Abdelhameed, A. S. Phylogenetic analyses of the spread of Clade I MPOX in African and non-African nations. Virus Genes 2025. [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, S.; Ross, S. R. APOBEC3 Proteins in Viral Immunity. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4565–4570. [CrossRef]

- O'Toole, Á.; Neher, R.A.; et al. APOBEC3 deaminase editing in mpox virus as evidence for sustained human transmission since at least 2016. Science 2023, 382, 600–606. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, T.; Shapiro, M.; Bhaduri-McIntosh, S.; MacCarthy, T. Evolutionary effects of the AID/APOBEC family of mutagenic enzymes on human gamma-herpesviruses. Virus Evol. 2019, 5, vey040. [CrossRef]

- Abdi, B.; Lambert-Niclot, S.; Wirden, M.; Jary, A.; Teyssou, E.; Sayon, S.; Palich, R.; Tubiana, R.; Simon, A.; Valantin, M.-A.; Katlama, C.; Morand-Joubert, L.; Calvez, V.; Marcelin, A.-G.; Soulie, C. Presence of HIV-1 G-to-A mutations linked to APOBEC editing is more prevalent in non-B HIV-1 subtypes and is associated with lower HIV-1 reservoir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2148–2152. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. A code within the genetic code: Codon usage regulates co-translational protein folding. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 145. [CrossRef]

- Sauna, Z. E.; Kimchi-Sarfaty, C. Understanding the contribution of synonymous mutations to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 683–691. [CrossRef]

- Karumathil, S.; Raveendran, N. T.; Ganesh, D.; Kumar NS, S.; Nair, R. R.; Dirisala, V. R. Evolution of Synonymous Codon Usage Bias in West African and Central African Strains of Monkeypox Virus. Evol. Bioinform. 2018, 14, 1176934318761368. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yu, J.; Qin, H.; Chen, X.; Wu, C.; Hong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Exploring the key genomic variation in monkeypox virus during the 2022 outbreak. BMC Genomic Data 2023, 24, 67. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, F.; Peng, Y.; Gong, X.; Fan, G.; Lin, Y.; Yang, L.; Shen, L.; Niu, S.; Liu, J.; Yin, Y.; Yuan, J.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Evolutionary trajectory and characteristics of Mpox virus in 2023 based on a large-scale genomic surveillance in Shenzhen, China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7452. [CrossRef]

- Zandi, M.; Shafaati, M.; Hosseini, F. Mechanisms of immune evasion of monkeypox virus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Shi, H.; Cheng, G. Mpox Virus: Its Molecular Evolution and Potential Impact on Viral Epidemiology. Viruses 2023, 15, 995. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).