Submitted:

31 May 2024

Posted:

04 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The development of pandemic preparedness and response (PPR) action plan:

- Establishing an active surveillance system:

- Identifying suspected cases:

- Samples collection:

- Viral DNA extraction:

- Laboratory investigations:

3. Results

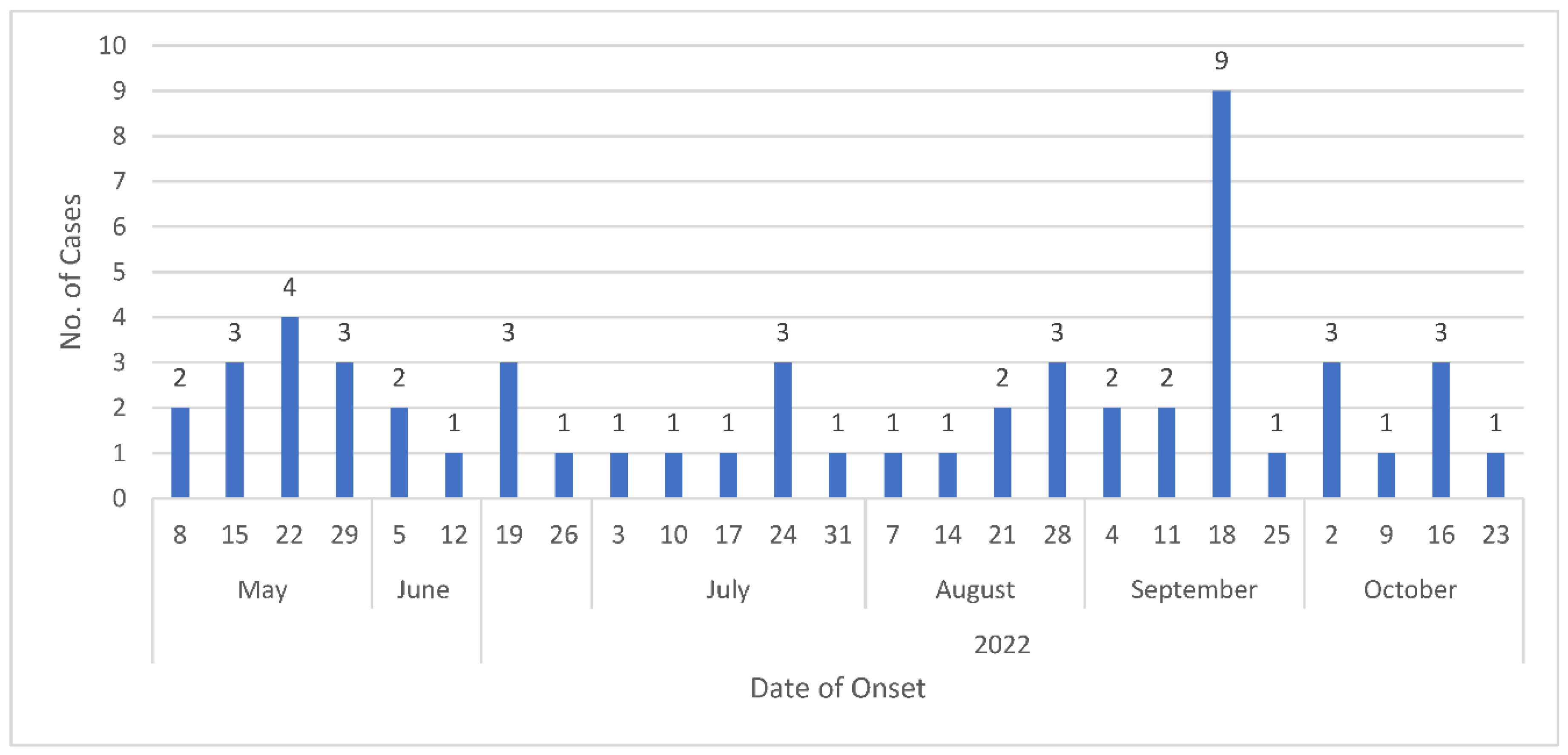

- Identification of suspected cases:

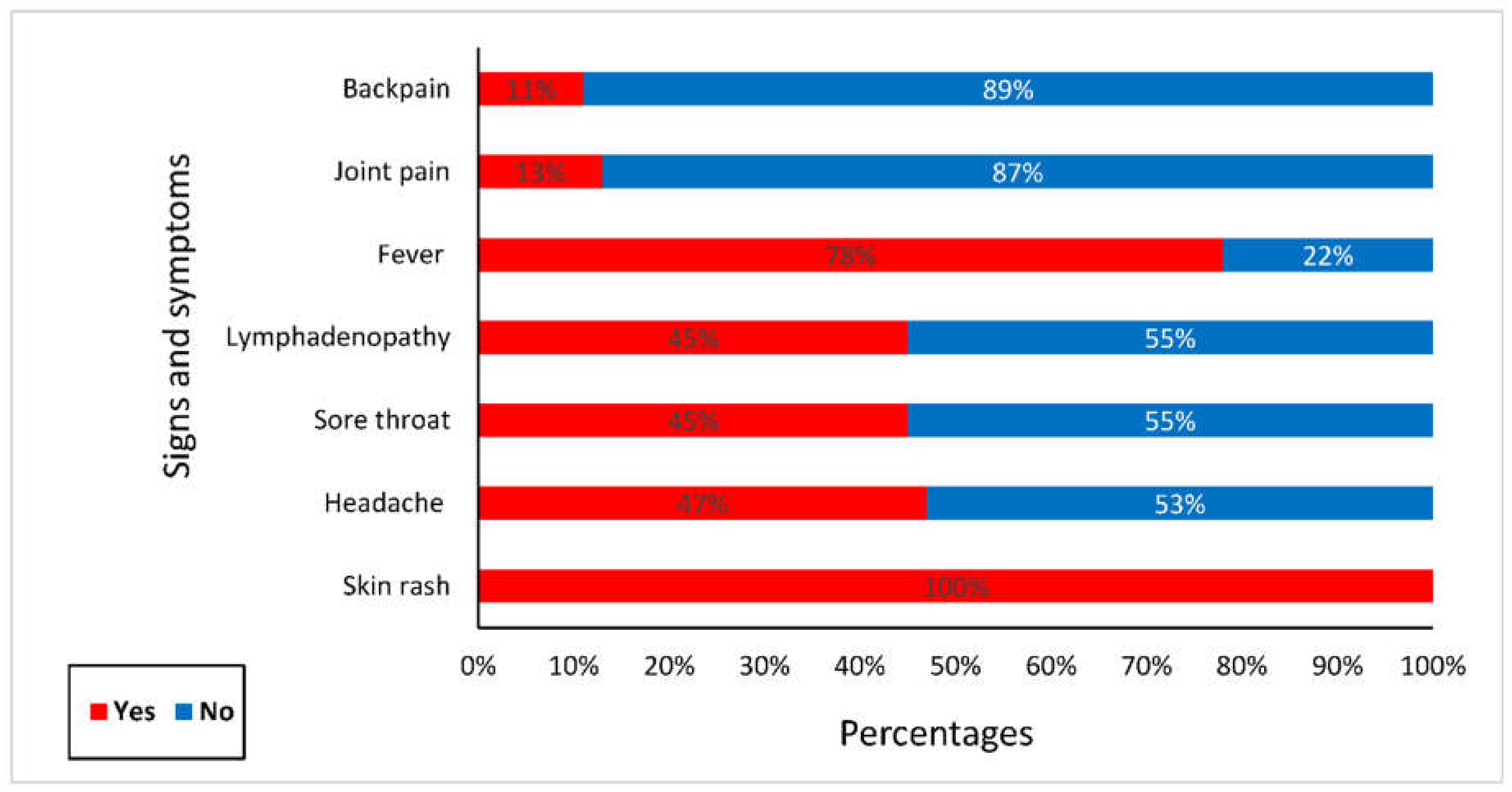

- Clinical presentations of suspected cases:

- Characteristics and disease outcome among confirmed cases:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Giulio, D.B.D.; Eckburg, P.B. Human Monkeypox: An Emerging Zoonosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jezek, Z.; Szczeniowski, M.; Paluku, K.M.; Mutombo, M.; Grab, B. Human Monkeypox: Confusion with Chickenpox. Acta Trop. 1988, 45, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Proietti, I.; Santoro, P.E.; Skroza, N.; Tieghi, T.; Bernardini, N.; Tolino, E.; Dybala, A.E.; Di Guardo, A.; Rallo, A.; Di Fraia, M. A Case Report of Monkeypox in an Adult Patient from Italy: Clinical and Dermoscopic Manifestations, Diagnosis and Management. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breman, J.G.; Henderson, D.A. Poxvirus Dilemmas—Monkeypox, Smallpox, and Biologic Terrorism; Mass Medical Soc, 1998; Vol. 339, pp. 556–559; ISBN 0028-4793.

- Mileto, D.; Riva, A.; Cutrera, M.; Moschese, D.; Mancon, A.; Meroni, L.; Giacomelli, A.; Bestetti, G.; Rizzardini, G.; Gismondo, M.R.; et al. New Challenges in Human Monkeypox Outside Africa: A Review and Case Report from Italy. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 49, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinori, A.; Mazzotta, V.; Vita, S.; Carletti, F.; Tacconi, D.; Lapini, L.E.; D’Abramo, A.; Cicalini, S.; Lapa, D.; Pittalis, S. Epidemiological, Clinical and Virological Characteristics of Four Cases of Monkeypox Support Transmission through Sexual Contact, Italy, May 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2200421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarín-Vicente, E.J.; Alemany, A.; Agud-Dios, M.; Ubals, M.; Suñer, C.; Antón, A.; Arando, M.; Arroyo-Andrés, J.; Calderón-Lozano, L.; Casañ, C. Clinical Presentation and Virological Assessment of Confirmed Human Monkeypox Virus Cases in Spain: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. The Lancet 2022, 400, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, J.; Graham, B.S. Smallpox Vaccines: Past, Present, and Future. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 1320–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarocostas, J. Monkeypox PHEIC Decision Hoped to Spur the World to Act. The Lancet 2022, 400, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sadig, S.M.; Mohamed, N.S.; Ahmed, E.S.; Alayeib, M.A.; Tahir, L.H.; Edris, A.M.M.; Ali, Y.; Siddig, E.E.; Ahmed, A. Obstacles Faced by Healthcare Providers during COVID-19 Pandemic in Sudan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 1615–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Mohamed, N.S.; EL-Sadig, S.M.; Fahal, L.A.; Abelrahim, Z.B.; Ahmed, E.S.; Siddig, E.E. COVID-19 in Sudan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppel, A.; Halim, M.I.; Kikon, R.; Mohamed, N.S.; Saebipour, M.R. Could COVID-19 Be Contained in Poor Populations by Herd Immunity Rather than by Strategies Designed for Affluent Societies or Potential Vaccine (s)? Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1863129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Mahmoud, I.; Eldigail, M.; Elhassan, R.M.; Weaver, S.C. The Emergence of Rift Valley Fever in Gedaref State Urges the Need for a Cross-Border One Health Strategy and Enforcement of the International Health Regulations. Pathogens 2021, 10, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, M.R.; Sorrell, E.M.; Standley, C.J. An Early Analysis of the World Bank’s Pandemic Fund: A New Fund for Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e011172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Mohamed, N.S. Arboviral Diseases: The Emergence of a Major yet Ignored Public Health Threat in Africa. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Salim, B.; Dietrich, I.; Zinsstag, J. Epidemics of Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) in Sudan between 2010 and 2020. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elduma, A.H.; LaBeaud, A.D.; A. Plante, J.; Plante, K.S.; Ahmed, A. High Seroprevalence of Dengue Virus Infection in Sudan: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 120. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markoff, L. Yellow Fever Outbreak in Sudan. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Elduma, A.; Eldigail, M.H.; Mhmoud, R.A.; Mohamed, N.S.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Dietrich, I.; Weaver, S.C. Unique Outbreak of Rift Valley Fever in Sudan, 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 3030–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Dietrich, I.; LaBeaud, A.D.; Lindsay, S.W.; Musa, A.; Weaver, S.C. Risks and Challenges of Arboviral Diseases in Sudan: The Urgent Need for Actions. Viruses 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Mohamed, N.S.; Zinsstag, J.; Siddig, E.E.; Khairy, A. Hepatitis E Virus Outbreak among Tigray War Refugees from Ethiopia, Sudan (Response). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 460–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hagelnur, A.A.; Eltigani, H.F.; Siddig, E.E. Cutaneous Tuberculosis of the Foot Clinically Mimicking Mycetoma: A Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddig, E. Fine Needle Aspiration: Past, Current Practice and Recent Developments. Biotech. Histochem. 2014, 89, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddig, E.E.; Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Bakhiet, S.M.; Mohamed, N.S.; Ahmed, E.S.; Fahal, A.H. Eumycetoma Medical Treatment: Past, Current Practice, Latest Advances and Perspectives. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 12, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.S.; Osman, H.A.; Muneer, M.S.; Samy, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Mohammed, A.O.; Siddig, E.E.; Abdel Hamid, M.M.; Ali, M.S.; Omer, R.A.; et al. Identifying Asymptomatic Leishmania Infections in Non-Endemic Villages in Gedaref State, Sudan. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altahir, O.; AbdElbagi, H.; Abubakr, M.; Siddig, E.E.; Ahmed, A.; Mohamed, N.S. Blood Meal Profile and Positivity Rate with Malaria Parasites among Different Malaria Vectors in Sudan. Malar. J. 2022, 21, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, N.S.; Ali, Y.; Muneer, M.S.; Siddig, E.E.; Sibley, C.H.; Ahmed, A. Malaria Epidemic in Humanitarian Crisis Settings the Case of South Kordofan State, Sudan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, N.S.; Abdelbagi, H.; Osman, H.A.; Ahmed, A.E.; Yousif, A.M.; Edris, Y.B.; Osman, E.Y.; Elsadig, A.R.; Siddig, E.E.; Mustafa, M. A Snapshot of Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria Drug Resistance Markers in Sudan: A Pilot Study. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Eldigail, M.; Elduma, A.; Breima, T.; Dietrich, I.; Ali, Y.; Weaver, S.C. First Report of Epidemic Dengue Fever and Malaria Co-Infections among Internally Displaced Persons in Humanitarian Camps of North Darfur, Sudan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 108, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; El-Amin, R.; Musa, A.M.; Elsayed, M.A.; Fahal, L.A.; Ahmed, E.S.; Ali, Y.; Nebie, I.E.; Mohamed, N.S.; Zinsstag, J.; et al. Guillain-Barre Syndrome Associated with COVID-19 Infection: A Case Series. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e6988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Siddig, E.E.; Mohamed, N.; Ahmed, A. Rift Valley Fever and Malaria Co-infection: A Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.T.H.; Abdelkhalig, R.E.; Hamid, E.; Ahmed, A.; Siddig, E.E. Recurrent Abdominal Wall Mass in a Hepatitis B-positive Male: An Unusual Case of Lumbar Mycetoma. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11, e8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddig, E.E.; Ahmed, A. When Parasites Stray from the Path: A Curious Case of Ectopic Cutaneous Schistosoma Haematobium. QJM Int. J. Med. 2023, 116, 794–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hemaida, M.A.; Hagelnur, A.A.; Eltigani, H.F.; Siddig, E.E. Sudden Emergence and Spread of Cutaneous Larva Migrans in Sudan: A Case Series Calls for Urgent Actions. IDCases 2023, 32, e01789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A. Urgent Call for a Global Enforcement of the Public Sharing of Health Emergencies Data: Lesson Learned from Serious Arboviral Disease Epidemics in Sudan. Int. Health 2020, 12, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, M.N.; Mohamed, F.I.; Osman, M.M.; Jadid, A.A.; Abdalrhman, I.K.; Yousif, A.M.; Alabid, T.; Edris, A.M.M.; Mohamed, N.S.; Siddig, E.E. Molecular Detection of Epstein-Barr Virus among Sudanese Patients Diagnosed with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Abubakr, M.; Sami, H.; Mahdi, I.; Mohamed, N.S.; Zinsstag, J. The First Molecular Detection of Aedes Albopictus in Sudan Associates with Increased Outbreaks of Chikungunya and Dengue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Siddig, E.E.; Hamed, J.; Mohamed, N.S.; Khairy, A.; Zinsstag, J. Hepatitis E Virus Outbreak among Tigray War Refugees from Ethiopia, Sudan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1722–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, Y.; Elmagboul, B.; Mohamed, O.; Elduma, A.; Bashab, H.; Mahamoud, A.; Khogali, H.; Elaagip, A.; Higazi, T. Dengue Fever in the Darfur Area, Western Sudan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagali, A.; Ahmed, A.; Makki, N.; Ismail, H.; Ajak, M.; Alene, K.A.; Weiss, D.J.; Mohammed, A.A.; Abubakr, M.; Cameron, E.; et al. Spatiotemporal Mapping of Malaria Incidence in Sudan Using Routine Surveillance Data. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddig, E.E.; El-Sadig, S.M.; Eltigani, H.F.; Musa, A.M.; Mohamed, N.S.; Ahmed, A. Delayed Cerebellar Ataxia Induced by Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria: A Rare Complication. Clin. Case Rep. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.S.; AbdElbagi, H.; Elsadig, A.R.; Ahmed, A.E.; Mohammed, Y.O.; Elssir, L.T.; Elnour, M.-A.B.; Ali, Y.; Ali, M.S.; Altahir, O. Assessment of Genetic Diversity of Plasmodium Falciparum Circumsporozoite Protein in Sudan: The RTS, S Leading Malaria Vaccine Candidate. Malar. J. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.S.; Ali, Y.; Abdalrahman, S.; Ahmed, A.; Siddig, E.E. The Use of Cholera Oral Vaccine for Containment of the 2019 Disease Outbreak in Sudan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Ahmed, A.; Siddig, E.E.; Mohamed, N.S. The Role of Integrated Programs in the Prevention of COVID-19 in a Humanitarian Setting. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairy, A.; Bashier, H.; Nuh, H.; Ahmed, N.; Ali, Y.; Izzoddeen, A.; Mohamed, S.; Osman, M.; Khader, Y. The Role of the Field Epidemiology Training Program in the Public Health Emergency Response: Sudan Armed Conflict 2023. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1300084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Mpox Cases by Age and Gender and Race and Ethnicity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/response/2022/demographics.html (accessed on 29 March 2024).

- Hennessee, I. Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years with Monkeypox — United States, May 17–September 24, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilera-Alonso, D.; Alonso-Cadenas, J.A.; Roguera-Sopena, M.; Lorusso, N.; San Miguel, L.G.; Calvo, C. Monkeypox Virus Infections in Children in Spain during the First Months of the 2022 Outbreak. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, e22–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, A.M.; Cenciarelli, O.; Colombe, S.; de Sousa, L.A.; Fischer, N.; Gossner, C.M.; Pires, J.; Scardina, G.; Aspelund, G.; Avercenko, M. A Large Multi-Country Outbreak of Monkeypox across 41 Countries in the WHO European Region, 7 March to 23 August 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2200620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Furth, A.M.T.; van der Kuip, M.; van Els, A.L.; Fievez, L.C.; van Rijckevorsel, G.G.; van den Ouden, A.; Jonges, M.; Welkers, M.R. Paediatric Monkeypox Patient with Unknown Source of Infection, the Netherlands, June 2022. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2200552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuente, S.M.; de Borja Nava, F.; Valerio, M.; Veintimilla, C.; Aguilera-Alonso, D. A Call for Attention: Pediatric Monkeypox Case in a Context of Changing Epidemiology. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, e548–e549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lun, W. Skin Manifestation of Human Monkeypox. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddig, E.E.; Eltigani, H.F.; Ahmed, A. Urgent Call to Protect Children and Their Health in Sudan. BMJ 2023, 382, p1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly-Yang, F.; Miranda-Sánchez, A.; Burgos-Blasco, B.; Fernández-Vigo, J.I.; Gegúndez-Fernández, J.A.; Díaz-Valle, D. Conjunctivitis in an Individual with Monkeypox. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022, 140, 1022–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, B.; Liang, S.Y.; Carius, B.M.; Chavez, S.; Gottlieb, M.; Koyfman, A.; Brady, W.J. Mimics of Monkeypox: Considerations for the Emergency Medicine Clinician. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 65, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddig, E.E.; Hay, R. Laboratory-Based Diagnosis of Scabies: A Review of the Current Status. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 116, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Giudice, P.; Fribourg, A.; Roudiere, L.; Gillon, J.; Decoppet, A.; Reverte, M. Familial Monkeypox Virus Infection Involving 2 Young Children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, N.J.; Brown, C.M.; Alvarado-Ramy, F.; Bair-Brake, H.; Benenson, G.A.; Chen, T.-H.; Demma, A.J.; Holton, N.K.; Kohl, K.S.; Lee, A.W.; et al. Travel and Border Health Measures to Prevent the International Spread of Ebola. MMWR Suppl. 2016, 65, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, P. Monkeypox Transmission—What We Know so Far. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, K.J.T.; Rizvi, R.; Willis, V.C.; Kassler, W.J.; Jackson, G.P. Effectiveness of Contact Tracing for Viral Disease Mitigation and Suppression: Evidence-Based Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e32468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, R.; Mohanty, A.; Reda, A.; Padhi, B.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Stigma during Monkeypox Outbreak. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1023519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.D.; Tschann, J.; Gurvey, J.E.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Ellen, J.M. Attitudes about Sexual Disclosure and Perceptions of Stigma and Shame. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2002, 78, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddig, E.E.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, E.S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Kunna, E.; El-Sadig, S.M.; Ali, Y.; Hassan, R.A.; Ali, E.T.; Mohamed, N.S. Knowledge and Attitudes towards Cervical Cancer Prevention among Women in Khartoum State, Sudan. Womens Health 2023, 19, 17455057231166286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, A.; McGee, K.; Farley, J.; Kwong, J.; McNabb, K.; Voss, J. Combating Stigma in the Era of Monkeypox—Is History Repeating Itself? J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2022, 33, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.M.; Chen, S.T.; Merola, J.F.; Mostaghimi, A.; Zhou, X.A.; Fett, N.; Smith, G.P.; Saavedra, A.P.; Noe, M.H.; Rosenbach, M. Monkeypox Outbreak, Vaccination, and Treatment Implications for the Dermatologic Patient: Review and Interim Guidance from the Medical Dermatology Society. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, E.A.; Sassine, J. Antivirals with Activity against Mpox: A Clinically Oriented Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, J.; Hazra, A.; Titanji, B.K. Mpox and HIV—Collision of Two Diseases. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2023, 20, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Americo, J.L.; Earl, P.L.; Moss, B. Virulence Differences of Mpox (Monkeypox) Virus Clades I, IIa, and IIb. 1 in a Small Animal Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2220415120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauldin, M.R.; McCollum, A.M.; Nakazawa, Y.J.; Mandra, A.; Whitehouse, E.R.; Davidson, W.; Zhao, H.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Doty, J. Exportation of Monkeypox Virus from the African Continent. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischauer, A.T.; Kile, J.C.; Davidson, M.; Fischer, M.; Karem, K.L.; Teclaw, R.; Messersmith, H.; Pontones, P.; Beard, B.A.; Braden, Z.H. Evaluation of Human-to-Human Transmission of Monkeypox from Infected Patients to Health Care Workers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, B.N.; Abdelmalik, P.; Cognat, S.; Grand, P.E.; Mott, J.A.; Pavlin, B.I.; Barakat, A.; Dowell, S.F.; Elmahal, O.; Golding, J.P.; et al. Defining Collaborative Surveillance to Improve Decision Making for Public Health Emergencies and Beyond. The Lancet 2023, 401, 1831–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatua, A.; Kar, T.K.; Nandi, S.K.; Jana, S.; Kang, Y. Impact of Human Mobility on the Transmission Dynamics of Infectious Diseases. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2020, 5, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, E.P.; Spruill-Harrell, B.M.; Taylor, M.K.; Lee, J.; Nywening, A.V.; Yang, Z.; Nichols, J.H.; Camp, J.V.; Owen, R.D.; Jonsson, C.B. Common Themes in Zoonotic Spillover and Disease Emergence: Lessons Learned from Bat- and Rodent-Borne RNA Viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsstag, J.; Crump, L.; Schelling, E.; Hattendorf, J.; Maidane, Y.O.; Ali, K.O.; Muhummed, A.; Umer, A.A.; Aliyi, F.; Nooh, F.; et al. Climate Change and One Health. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018, 365, fny085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Mohamed, N.S.; Siddig, E.E.; Algaily, T.; Sulaiman, S.; Ali, Y. The Impacts of Climate Change on Displaced Populations: A Call for Action. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Republic of the Sudan: Mission Report, 9-13 October 2016. 2017.

- Siddig, E.E.; Eltigani, H.F.; Ahmed, A. Healing the Unseen Wounds: Sudan’s Humanitarian Crisis Traumatizing a Nation. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 89, 103764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddig, E.E.; Eltigani, H.F.; Ali, E.T.; Bongomin, F.; Ahmed, A. Sustaining Hope amid Struggle: The Plight of Cancer Patients in Sudan’s Ongoing War. J. Cancer Policy 2023, 38, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadul, E.S.; Alrawa, S.S.; Eltigani, H.F.; Ahmed, A.; Siddig, E.E. The Unraveling of Sudan’s Health System: Catastrophic Consequences of Ongoing Conflict. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2023, 39, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddig, E.E.; Eltigani, H.F.; Ahmed, A. Urgent Call to Protect Children and Their Health in Sudan. BMJ 2023, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pillars | Structure | Activities | Note |

| Coordination | Mpox taskforce committee was established at state level (Federal and state level) and seven sub-committees at each locality level (locality level). | Coordinates between the stakeholders of human, animal, and environmental health for the implementation of the preparedness, surveillance, and response at locality levels. | The committee was led by the Ministry of Health and members, including animals health authorities, United Nations (UN) agencies, and other non-governmental (NGOs) partners. |

| Disease surveillance system | Enhancement of surveillance systems among both animals and humans to facilitate early detection and response for Mpox cases. | Building capacity of integrated surveillance conducted for 596 cadres who have received training in Mpox from 298 health facilities (HFs) across seven localities, additionally 400 community volunteers were trained on community-based surveillance (CBS) for Mpox. | Case definition on Mpox distributed in all HFs and provided to CBS volunteers. |

| Laboratory | Building the diagnostic capacity and readiness to compensate serve and/or country-wide massive screening of Mpox if needed. | Three technical officers and 3 technicians were trained on the basic and advanced diagnostic tools for Mpox. Stocks of efficient diagnostic kits were mobilized, secured, and calibrated. |

Referral system was established and operated by the rapid response teams (RRTs). |

| Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) | Establishment of 7 RRTs and equipping them with necessary resources to enable early detection and response. | 7 RRTs received training on Mpox case investigation across seven localities. | The team was composed from an epidemiologist, a laboratory technician, a clinician, an infection, prevention and control (IPC) specialist, and a public health officer) |

| Case management and IPC | Training for healthcare providers on Mpox case management and IPC in isolation centres | 298 Healthcare providers received training in case management and IPC | One Isolation centre was identified (Ibrahim Malik Hospital). A referral system was established at airports and other localities. |

| Risk communication and community engagement | Social behavioural change in coordination with partners through various modalities of risk communication | Raising awareness sessions were delivered through TV, Radio and social media, mosques, mobile microphones, and health promotion theatres across seven localities. | Health promotion activities and engagements covered more than 70% of the communities. |

| |

Cases | AR/10000 | CFR/100 | |

| Suspected | Confirmed | |||

| Khartoum | 17 | 0 | 0.20 | 0 |

| Jabal Awliya | 9 | 0 | 0.94 | 0 |

| Omdurman | 8 | 1 | 0.14 | 0 |

| Bahri | 4 | 0 | 0.06 | 0 |

| Sharg El Nile | 8 | 1 | 0.09 | 0 |

| Karrari | 4 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 |

| UmBada | 5 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 |

| Total | 55 | 2 | 0.11 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).