Submitted:

03 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

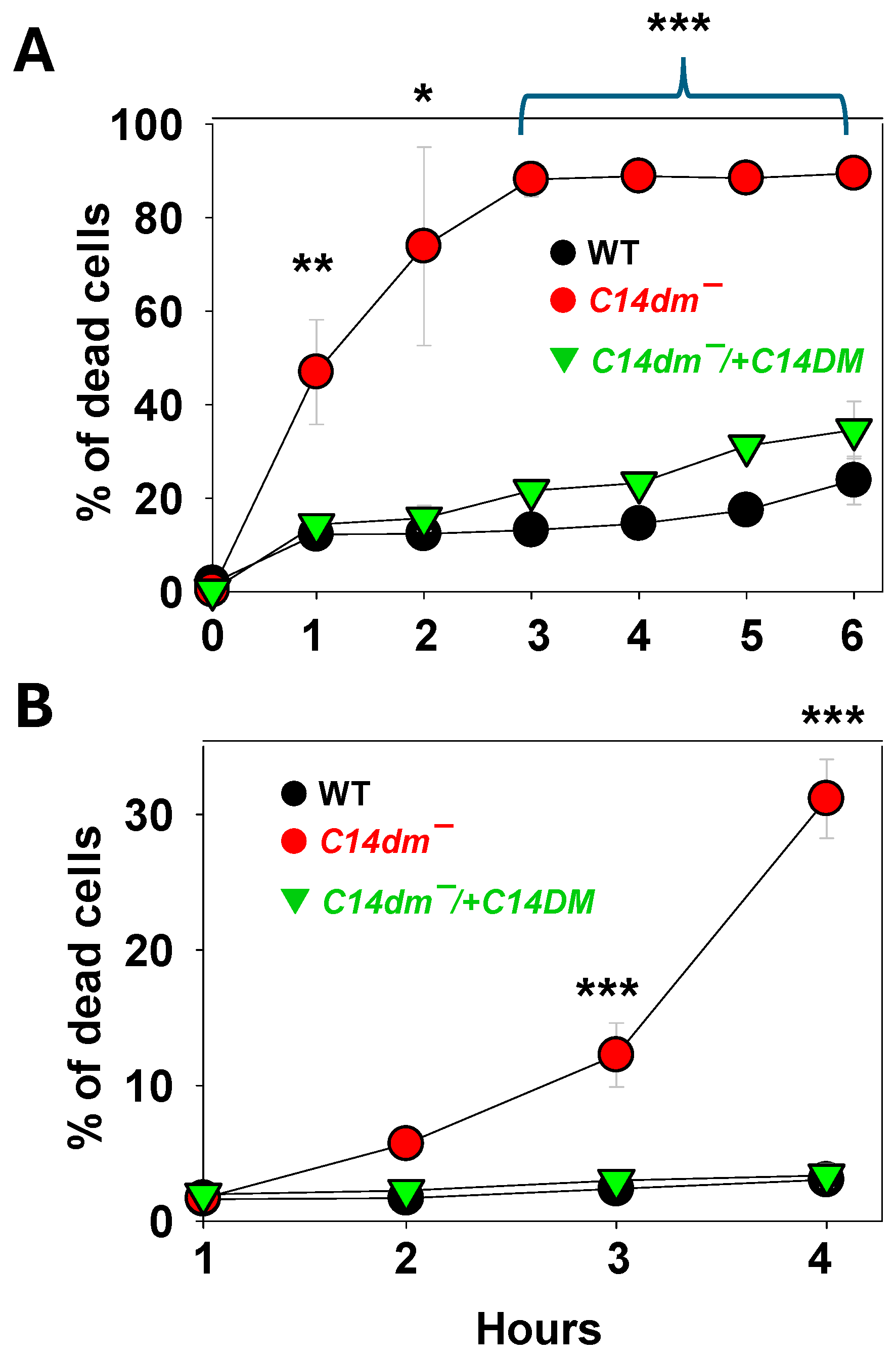

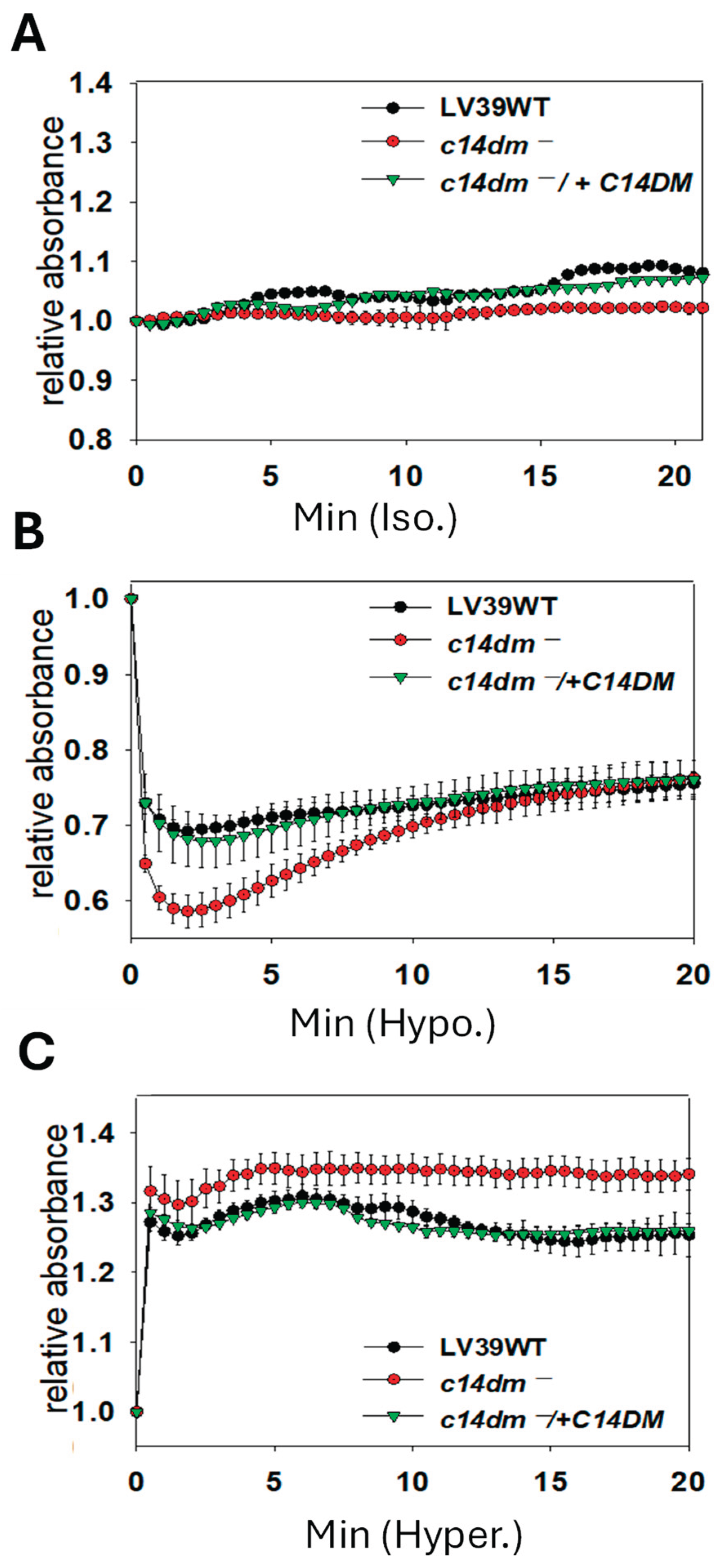

2.1. C14dm¯ Mutants Are Hypersensitive to Triton X-100, Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), and Osmotic Changes

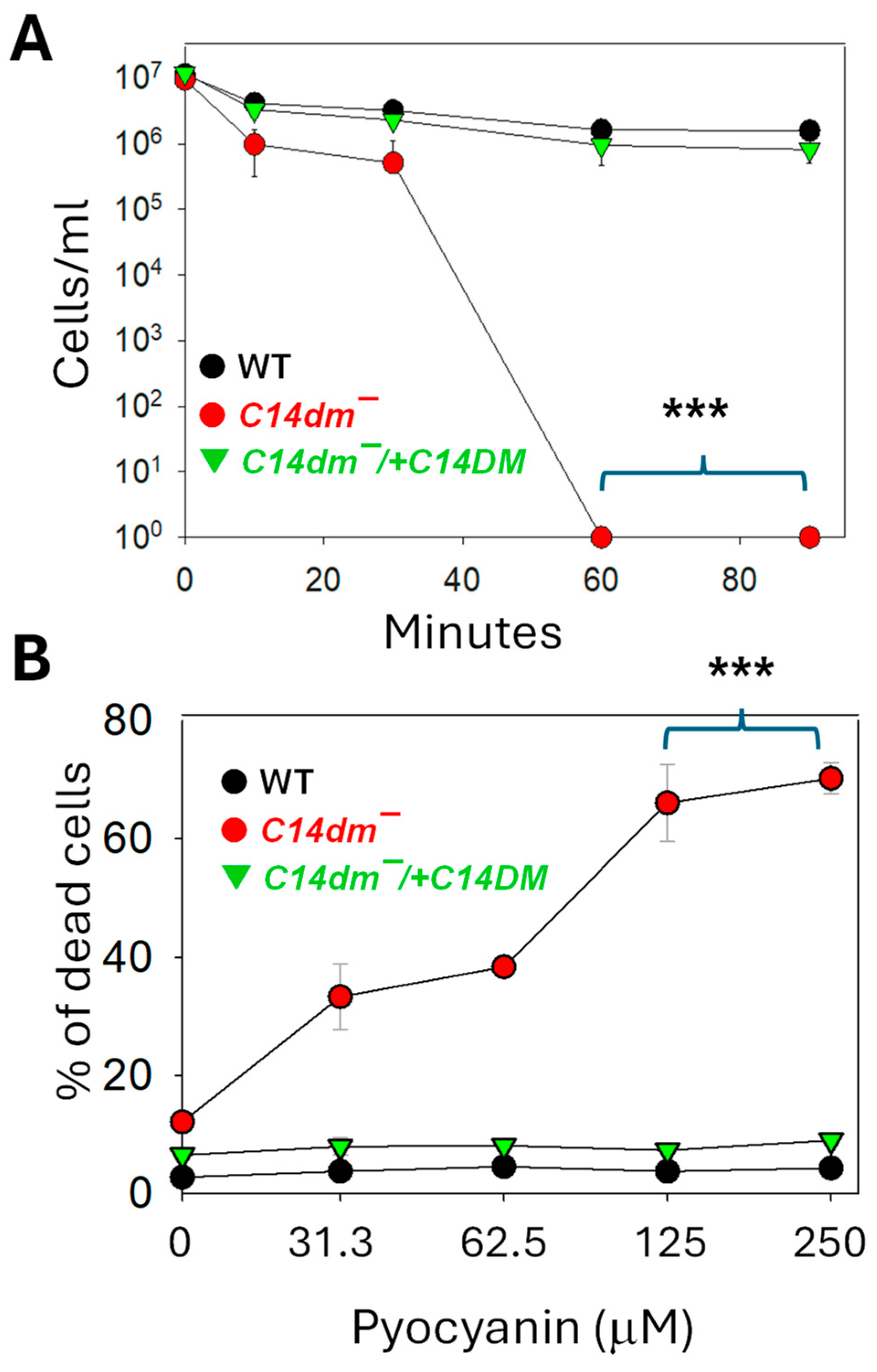

2.2. C14dm¯ Mutants Show Hypersensitivity to Pseudomonas aeruginosa Spent Medium and Pyocyanin

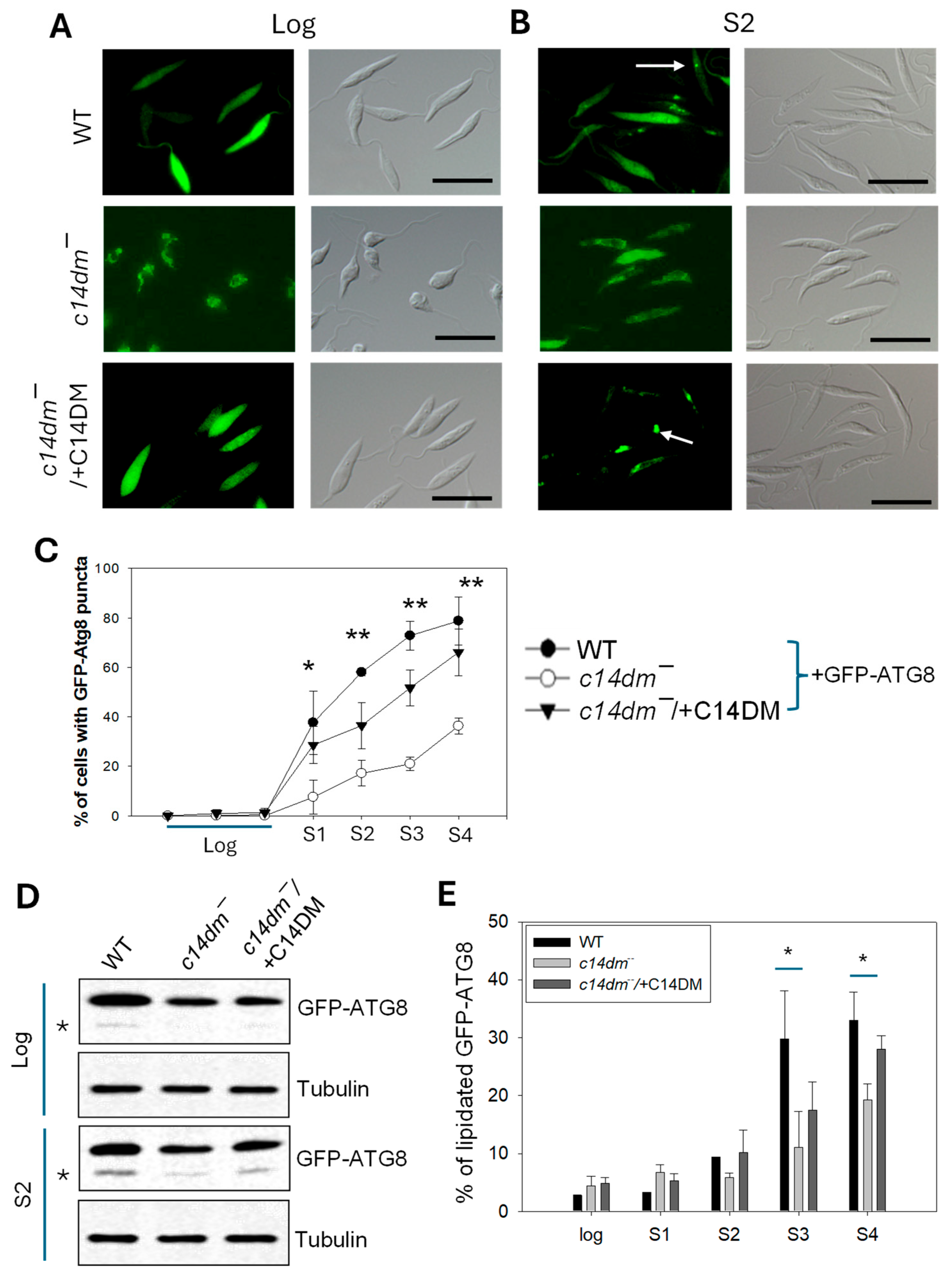

2.3. C14dm¯ Mutants Show Autophagy Defects

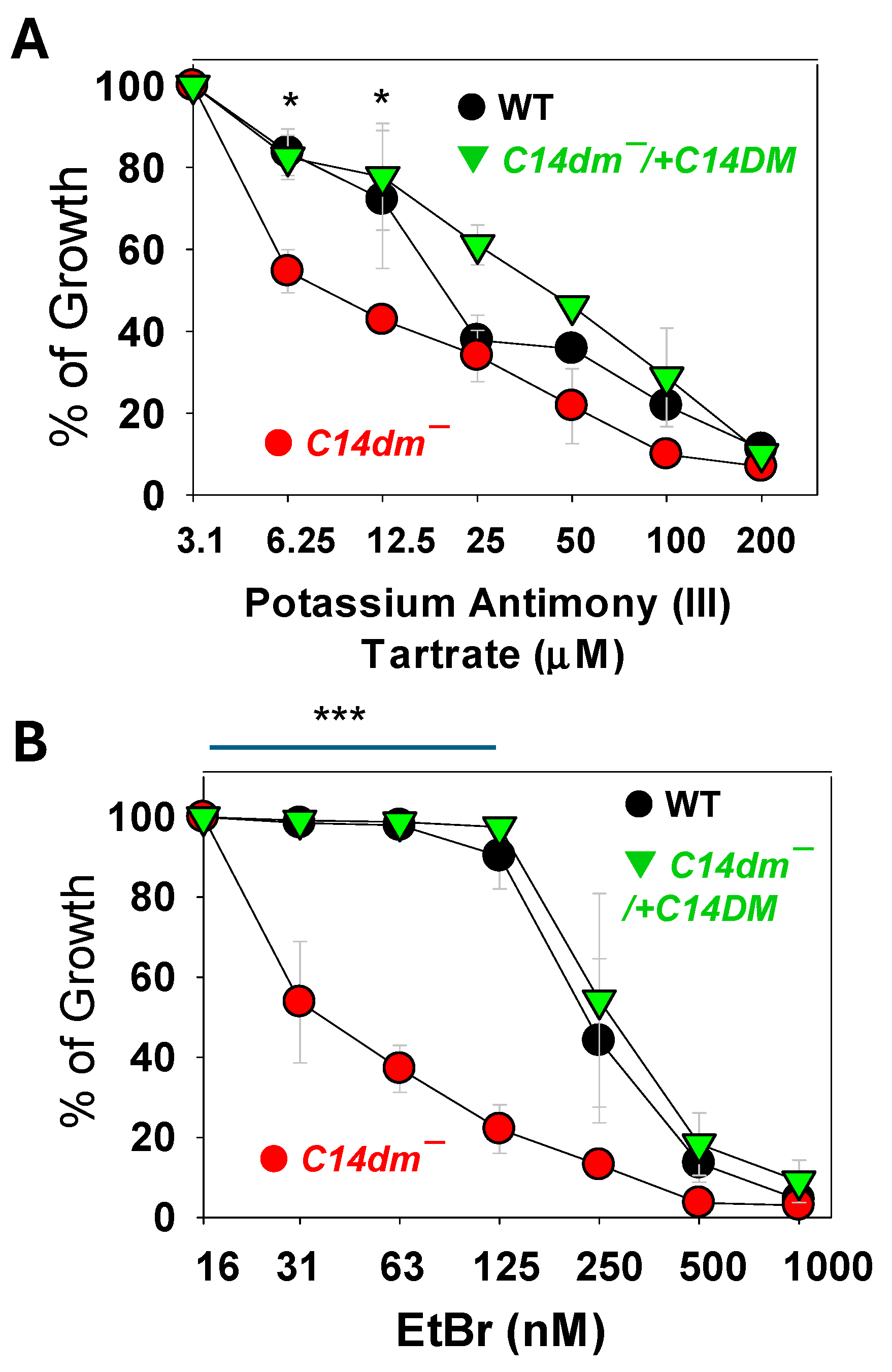

2.4. C14dm‾ Parasites Show Increased Sensitivity to Antimony and Ethidium Bromide (EtBr)

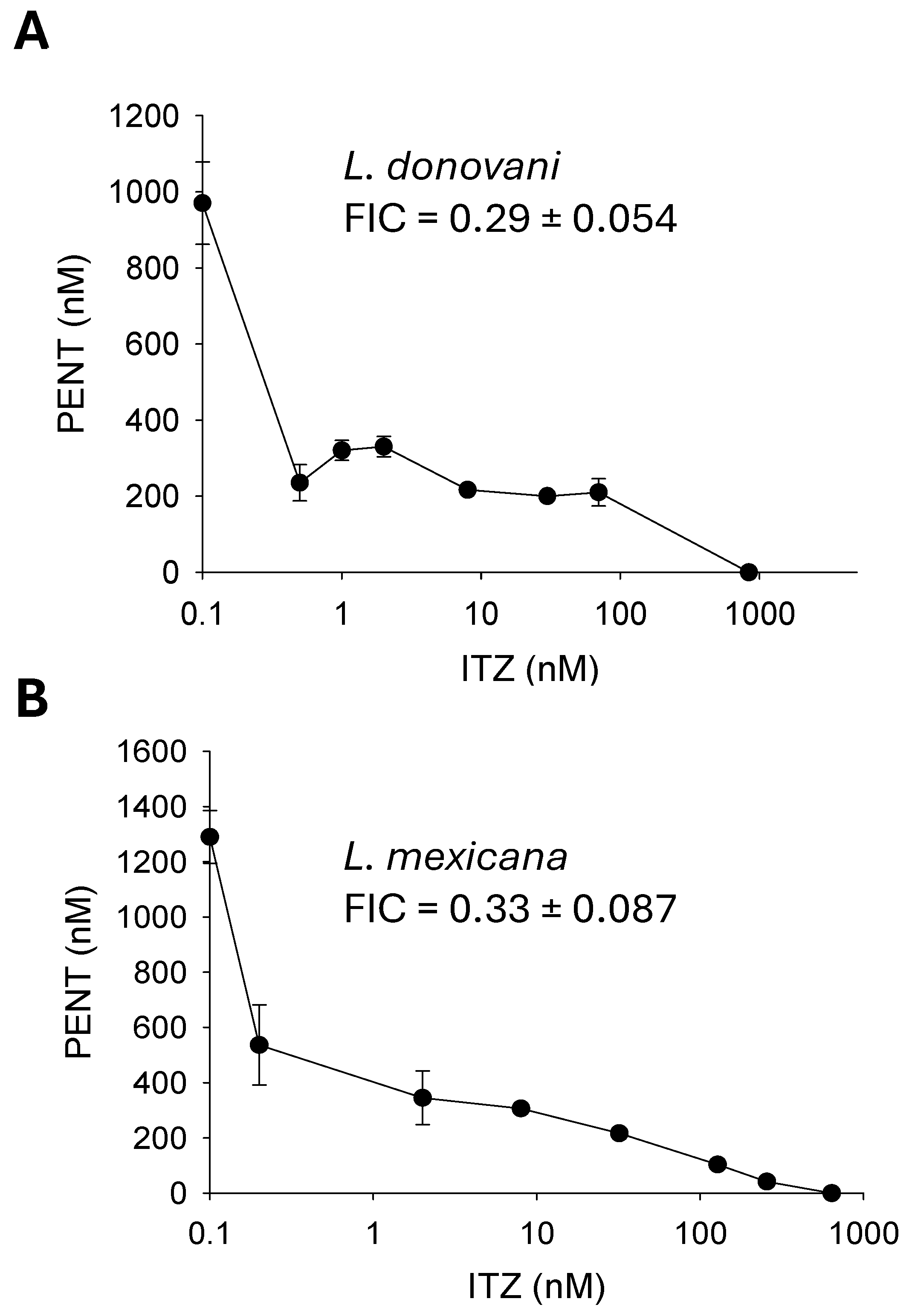

2.5. Synergistic Inhibition of Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania donovani with Pentamidine (PENT) and Itraconazole (ITZ)

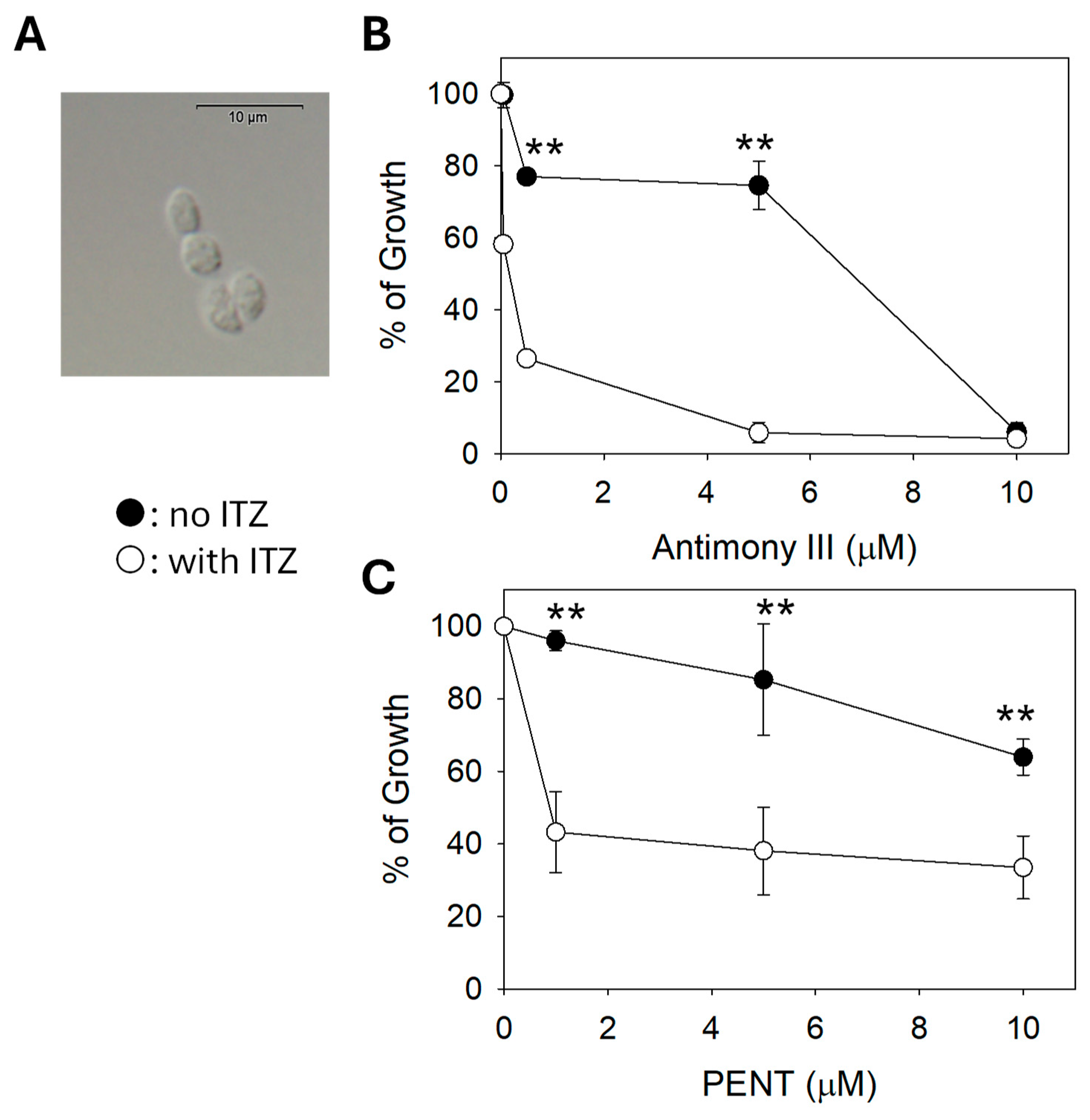

2.6. C14DM Inhibition Enhances Drug Sensitivity in L. mexicana axenic Amastigotes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Leishmania Culture

4.3. To Determine the Effects of Membrane Perturbing agents, P. aeruginosa PA14 Conditioned Medium, Pyocyanin, and Chemical Inhibitors

4.4. Synergy Calculations

4.5. Response to Osmotic Stress

4.6. Autophagy Assays and Microscopy

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pace, D. Leishmaniasis. The Journal of infection 2014, 69 Suppl 1, S10-18. [CrossRef]

- Uliana, S.R.B.; Trinconi, C.T.; Coelho, A.C. Chemotherapy of leishmaniasis: present challenges. Parasitology 2018, 145, 464-480. [CrossRef]

- de Souza, W.; Rodrigues, J.C. Sterol Biosynthesis Pathway as Target for Anti-trypanosomatid Drugs. Interdisciplinary perspectives on infectious diseases 2009, 2009, 642502. [CrossRef]

- de Macedo-Silva, S.T.; de Souza, W.; Rodrigues, J.C. Sterol Biosynthesis Pathway as an Alternative for the Anti-Protozoan Parasite Chemotherapy. Current medicinal chemistry 2015, 22, 2186-2198. [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, S.; Kalra, S.; Bari, V.K. Insights into the role of sterol metabolism in antifungal drug resistance: a mini-review. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1409085. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Hsu, F.F.; Baykal, E.; Huang, J.; Zhang, K. Sterol Biosynthesis Is Required for Heat Resistance but Not Extracellular Survival in Leishmania. PLoS pathogens 2014, 10, e1004427. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Moitra, S.; Xu, W.; Hernandez, V.; Zhang, K. Sterol 14-alpha-demethylase is vital for mitochondrial functions and stress tolerance in Leishmania major. PLoS pathogens 2020, 16, e1008810. [CrossRef]

- Karamysheva, Z.N.; Moitra, S.; Perez, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Tikhonova, E.B.; Karamyshev, A.L.; Zhang, K. Unexpected Role of Sterol Synthesis in RNA Stability and Translation in Leishmania. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- McCall, L.I.; El Aroussi, A.; Choi, J.Y.; Vieira, D.F.; De Muylder, G.; Johnston, J.B.; Chen, S.; Kellar, D.; Siqueira-Neto, J.L.; Roush, W.R.; et al. Targeting Ergosterol biosynthesis in Leishmania donovani: essentiality of sterol 14 alpha-demethylase. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2015, 9, e0003588. [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, L.B.; Tinti, M.; Wall, R.J.; Weidt, S.K.; Corpas-Lopez, V.; Dey, G.; Smith, T.K.; Fairlamb, A.H.; Barrett, M.P.; Wyllie, S. Sterol 14-alpha demethylase (CYP51) activity in Leishmania donovani is likely dependent upon cytochrome P450 reductase 1. PLoS pathogens 2024, 20, e1012382. [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, V.A.; Francesconi, F.; Ramasawmy, R.; Romero, G.A.S.; Alecrim, M. Failure of fluconazole in treating cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania guyanensis in the Brazilian Amazon: An open, nonrandomized phase 2 trial. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2018, 12, e0006225. [CrossRef]

- Beach, D.H.; Goad, L.J.; Holz, G.G., Jr. Effects of antimycotic azoles on growth and sterol biosynthesis of Leishmania promastigotes. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 1988, 31, 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.S.; Jesus, J.A.; Bezerra-Souza, A.; Laurenti, M.D.; Ribeiro, S.P.; Passero, L.F.D. Activity of Fenticonazole, Tioconazole and Nystatin on New World Leishmania Species. Curr Top Med Chem 2018, 18, 2338-2346. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, O.L.; Rosales-Chilama, M.; Quintero, N.; Travi, B.L.; Wetzel, D.M.; Gomez, M.A.; Saravia, N.G. Potency and Preclinical Evidence of Synergy of Oral Azole Drugs and Miltefosine in an Ex Vivo Model of Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis Infection. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2022, 66, e0142521. [CrossRef]

- Joice, A.C.; Yang, S.; Farahat, A.A.; Meeds, H.; Feng, M.; Li, J.; Boykin, D.W.; Wang, M.Z.; Werbovetz, K.A. Antileishmanial Efficacy and Pharmacokinetics of DB766-Azole Combinations. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2018, 62. [CrossRef]

- Koley, D.; Bard, A.J. Triton X-100 concentration effects on membrane permeability of a single HeLa cell by scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2010, 107, 16783-16787. [CrossRef]

- Kapler, G.M.; Coburn, C.M.; Beverley, S.M. Stable transfection of the human parasite Leishmania major delineates a 30-kilobase region sufficient for extrachromosomal replication and expression. Mol Cell Biol 1990, 10, 1084-1094. [CrossRef]

- Dagger, F.; Valdivieso, E.; Marcano, A.K.; Ayesta, C. Regulatory volume decrease in Leishmania mexicana: effect of anti-microtubule drugs. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2013, 108, 84-90. [CrossRef]

- Tom, A.; Kumar, N.P.; Kumar, A.; Saini, P. Interactions between Leishmania parasite and sandfly: a review. Parasitology research 2023, 123, 6. [CrossRef]

- Campolina, T.B.; Villegas, L.E.M.; Monteiro, C.C.; Pimenta, P.F.P.; Secundino, N.F.C. Tripartite interactions: Leishmania, microbiota and Lutzomyia longipalpis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020, 14, e0008666. [CrossRef]

- Borbon, T.Y.; Scorza, B.M.; Clay, G.M.; Lima Nobre de Queiroz, F.; Sariol, A.J.; Bowen, J.L.; Chen, Y.; Zhanbolat, B.; Parlet, C.P.; Valadares, D.G.; et al. Coinfection with Leishmania major and Staphylococcus aureus enhances the pathologic responses to both microbes through a pathway involving IL-17A. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2019, 13, e0007247. [CrossRef]

- Al-Alousy, N.W.; Al-Nasiri, F.S. Bacterial infections associated with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Salah Al-Din province, Iraq. Microb Pathog 2025, 198, 107144. [CrossRef]

- Karimian, F.; Koosha, M.; Choubdar, N.; Oshaghi, M.A. Comparative analysis of the gut microbiota of sand fly vectors of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis (ZVL) in Iran; host-environment interplay shapes diversity. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2022, 16, e0010609. [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J.; Goldufsky, J.W.; Seu, M.Y.; Dorafshar, A.H.; Shafikhani, S.H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Cytotoxins: Mechanisms of Cytotoxicity and Impact on Inflammatory Responses. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Barbieri, J.T. Intracellular trafficking of Pseudomonas ExoS, a type III cytotoxin. Traffic 2007, 8, 1331-1345. [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, A.A.; Kamer, A.M.A.; Al-Monofy, K.B.; Al-Madboly, L.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa's greenish-blue pigment pyocyanin: its production and biological activities. Microb Cell Fact 2023, 22, 110. [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, T.; Vasconcelos, U. Colour Me Blue: The History and the Biotechnological Potential of Pyocyanin. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.A.; Smith, T.K.; Cull, B.; Mottram, J.C.; Coombs, G.H. ATG5 is essential for ATG8-dependent autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis in Leishmania major. PLoS pathogens 2012, 8, e1002695. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.A.; Woods, K.L.; Juliano, L.; Mottram, J.C.; Coombs, G.H. Characterization of unusual families of ATG8-like proteins and ATG12 in the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Autophagy 2009, 5, 159-172. [CrossRef]

- Besteiro, S.; Williams, R.A.; Morrison, L.S.; Coombs, G.H.; Mottram, J.C. Endosome sorting and autophagy are essential for differentiation and virulence of Leishmania major. The Journal of biological chemistry 2006, 281, 11384-11396. [CrossRef]

- J, B.; M, B.M.; Chanda, K. An Overview on the Therapeutics of Neglected Infectious Diseases-Leishmaniasis and Chagas Diseases. Frontiers in chemistry 2021, 9, 622286. [CrossRef]

- Riou, G.; Delain, E. Abnormal circular DNA molecules induced by ethidium bromide in the kinetoplast of Trypanosoma cruzi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1969, 64, 618-625. [CrossRef]

- Roy Chowdhury, A.; Bakshi, R.; Wang, J.; Yildirir, G.; Liu, B.; Pappas-Brown, V.; Tolun, G.; Griffith, J.D.; Shapiro, T.A.; Jensen, R.E.; et al. The killing of African trypanosomes by ethidium bromide. PLoS pathogens 2010, 6, e1001226. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Padmanabhan, P.K.; Sahani, M.H.; Barrett, M.P.; Madhubala, R. Roles for mitochondria in pentamidine susceptibility and resistance in Leishmania donovani. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 2006, 145, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Hallander, H.O.; Dornbusch, K.; Gezelius, L.; Jacobson, K.; Karlsson, I. Synergism between aminoglycosides and cephalosporins with antipseudomonal activity: interaction index and killing curve method. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 1982, 22, 743-752. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Goyal, N.; Rastogi, A.K. In vitro cultivation and characterization of axenic amastigotes of Leishmania. Trends in parasitology 2001, 17, 150-153. [CrossRef]

- Tabbabi, A.; Mizushima, D.; Yamamoto, D.S.; Zhioua, E.; Kato, H. Comparative analysis of the microbiota of sand fly vectors of Leishmania major and L. tropica in a mixed focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in southeast Tunisia; ecotype shapes the bacterial community structure. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2024, 18, e0012458. [CrossRef]

- Fraihi, W.; Fares, W.; Perrin, P.; Dorkeld, F.; Sereno, D.; Barhoumi, W.; Sbissi, I.; Cherni, S.; Chelbi, I.; Durvasula, R.; et al. An integrated overview of the midgut bacterial flora composition of Phlebotomus perniciosus, a vector of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis in the Western Mediterranean Basin. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2017, 11, e0005484. [CrossRef]

- Cecilio, P.; Rogerio, L.A.; T, D.S.; Tang, K.; Willen, L.; Iniguez, E.; Meneses, C.; Chaves, L.F.; Zhang, Y.; Dos Santos Felix, L.; et al. Leishmania sand fly-transmission is disrupted by Delftia tsuruhatensis TC1 bacteria. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 3571. [CrossRef]

- Sant'Anna, M.R.; Diaz-Albiter, H.; Aguiar-Martins, K.; Al Salem, W.S.; Cavalcante, R.R.; Dillon, V.M.; Bates, P.A.; Genta, F.A.; Dillon, R.J. Colonisation resistance in the sand fly gut: Leishmania protects Lutzomyia longipalpis from bacterial infection. Parasites & vectors 2014, 7, 329. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.H.; Bahr, S.M.; Serafim, T.D.; Ajami, N.J.; Petrosino, J.F.; Meneses, C.; Kirby, J.R.; Valenzuela, J.G.; Kamhawi, S.; Wilson, M.E. The Gut Microbiome of the Vector Lutzomyia longipalpis Is Essential for Survival of Leishmania infantum. mBio 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Francisco, P.H.; Brocchi, M.; Giorgio, S. Leishmania and its relationships with bacteria. Future microbiology 2022, 17, 199-218. [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Shaha, C. Leishmania donovani parasite requires Atg8 protein for infectivity and survival under stress. Cell death & disease 2019, 10, 808. [CrossRef]

- Haldar, A.K.; Sen, P.; Roy, S. Use of antimony in the treatment of leishmaniasis: current status and future directions. Mol Biol Int 2011, 2011, 571242. [CrossRef]

- Wyllie, S.; Cunningham, M.L.; Fairlamb, A.H. Dual action of antimonial drugs on thiol redox metabolism in the human pathogen Leishmania donovani. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 39925-39932. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yan, R.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; He, Z.; Xiao, J.; Li, K.; Liu, G.; Ning, Q.; Li, Y. Progress in antileishmanial drugs: Mechanisms, challenges, and prospects. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2025, 19, e0012735. [CrossRef]

- Bates, P.A. Axenic culture of Leishmania amastigotes. Parasitology today (Personal ed 1993, 9, 143-146. [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.S.; Schwarz, J.K.; Turco, S.J.; Beverley, S.M. Use of the green fluorescent protein as a marker in transfected Leishmania. Molecular and biochemical parasitology 1996, 77, 57-64. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).