Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

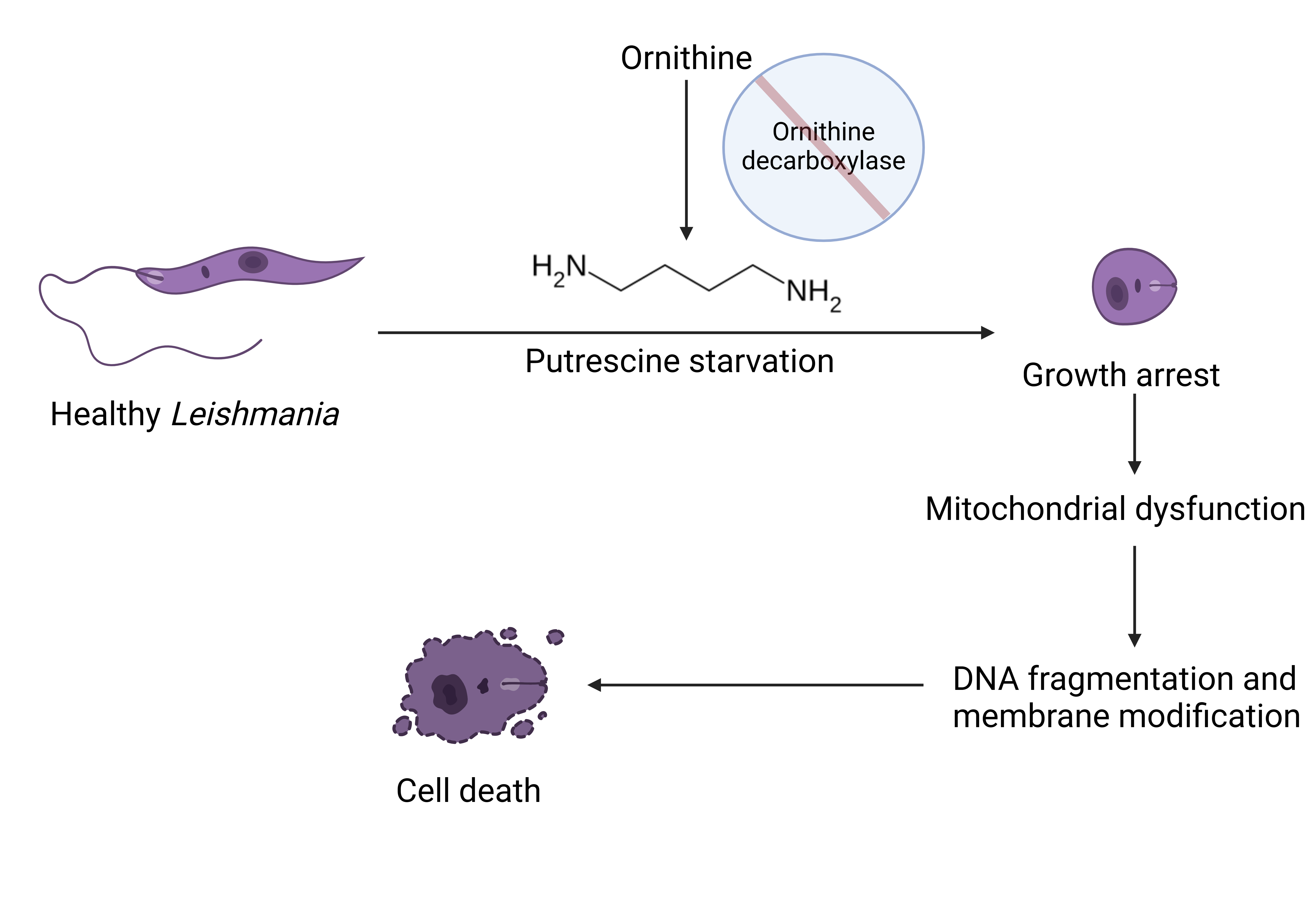

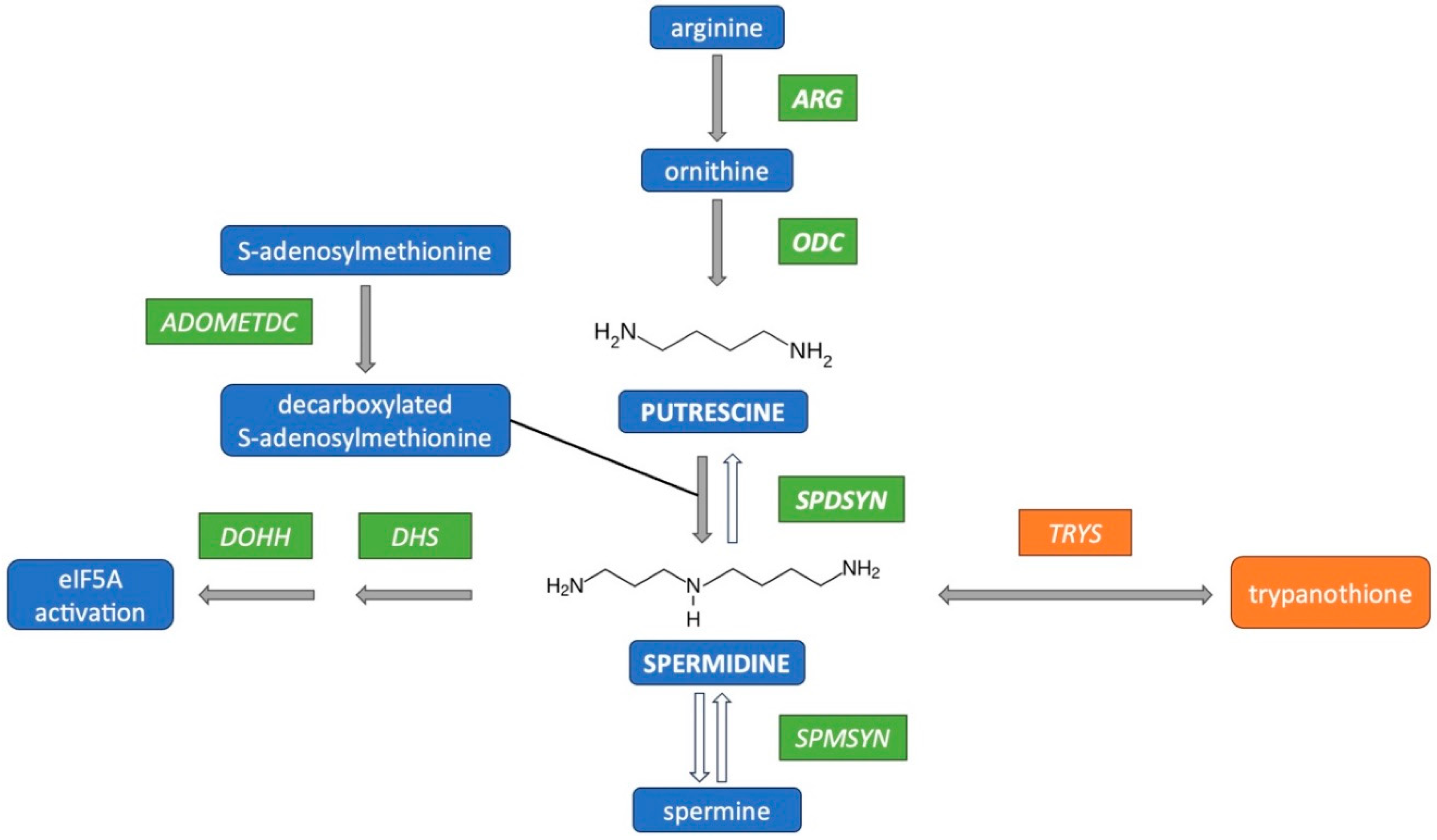

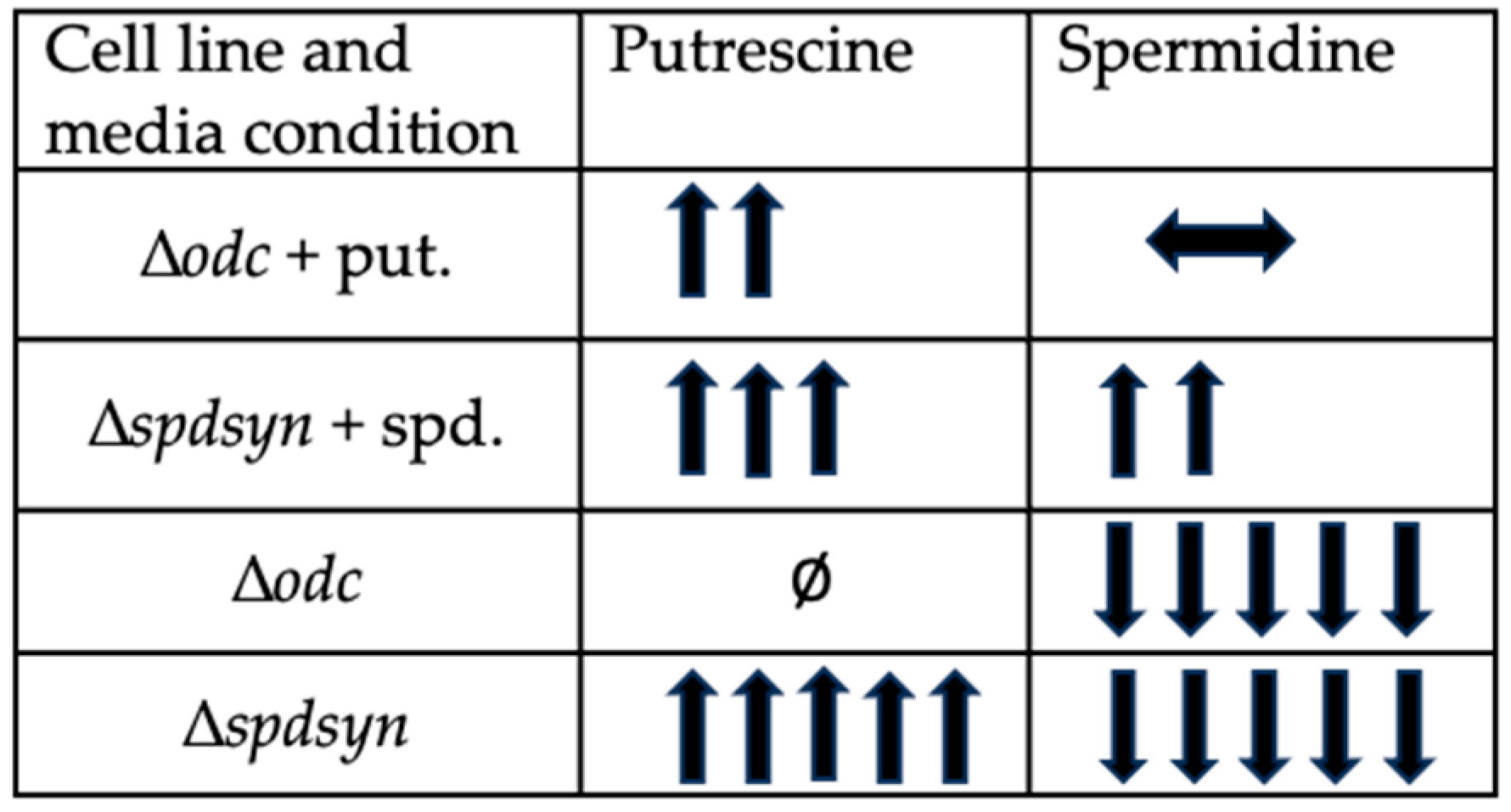

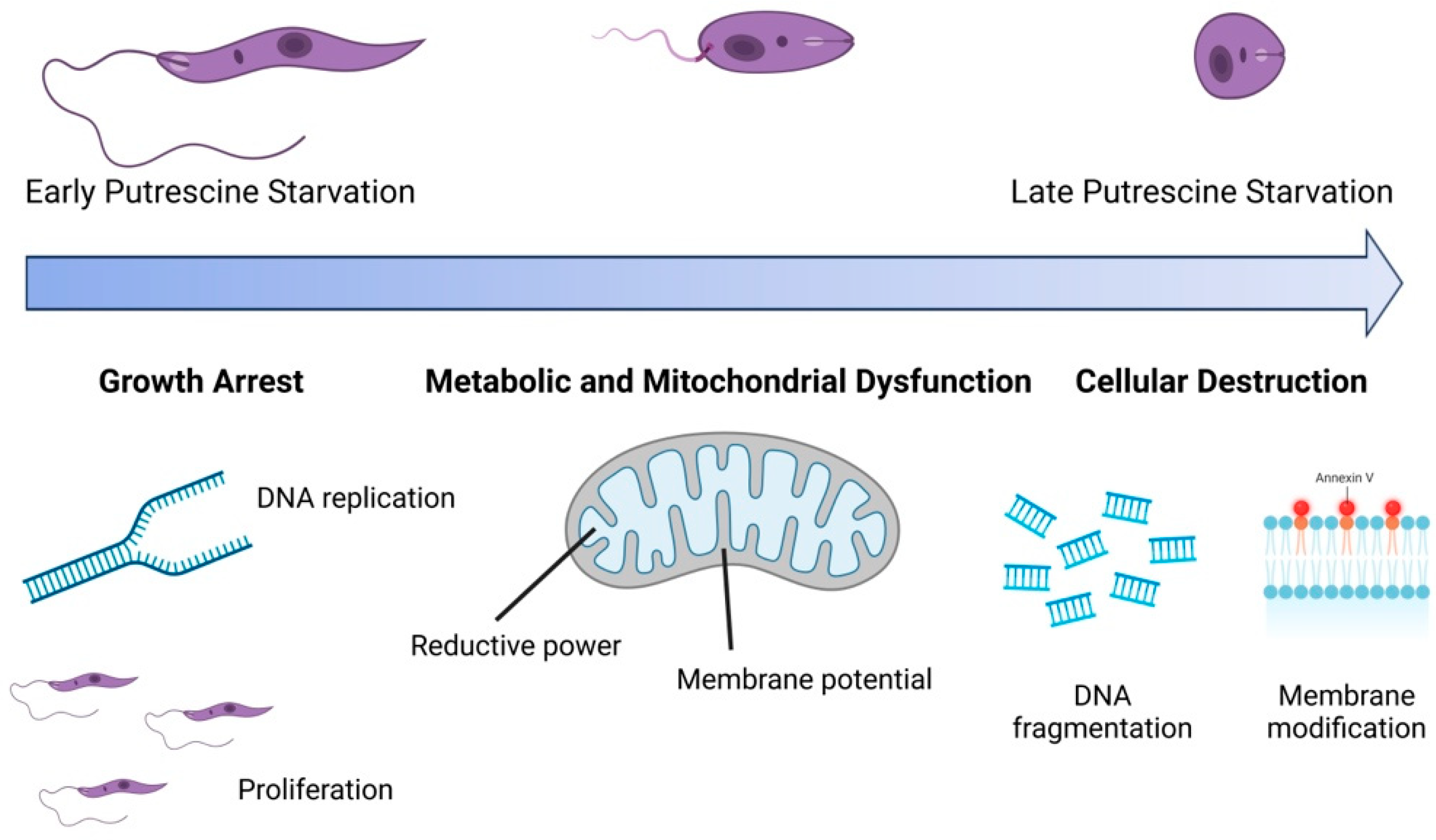

The polyamine pathway in Leishmania parasites has emerged as a promising target for therapeutic intervention, yet the functions of polyamines in parasites remain largely unexplored. Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and spermidine synthase (SPDSYN) catalyze the sequential conversion of ornithine to putrescine and spermidine. We previously described that Leishmania donovani Δodc and Δspdsyn mutants exhibit markedly reduced growth in vitro and diminished infectivity in mice, with the effect being most pronounced in putrescine-depleted Δodc mutants. Here, we report that in polyamine-free media, ∆odc mutants arrested proliferation and replication, while ∆spdsyn mutants showed a slow growth and replication phenotype. Starved ∆odc parasites also exhibited a marked reduction in metabolism, which was not observed in the starved ∆spdsyn cells. In contrast, both mutants displayed mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization. Hallmarks of apoptosis, DNA fragmentation and membrane modifications, were observed in Δodc mutants incubated in polyamine-free media. These results show that putrescine depletion had an immediate detrimental effect on cell growth, replication, and mitochondrial metabolism and caused an apoptosis-like death phenotype. Our findings establish ODC as the most promising therapeutic target within the polyamine biosynthetic pathway for treating leishmaniasis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.3. Proliferation Assay

2.4. Replication Assay

2.5. Metabolism Assay

2.6. Assessment of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

2.7. DNA Fragmentation Assay

2.8. Membrane Modifications Assay

2.9. Data Visualization and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

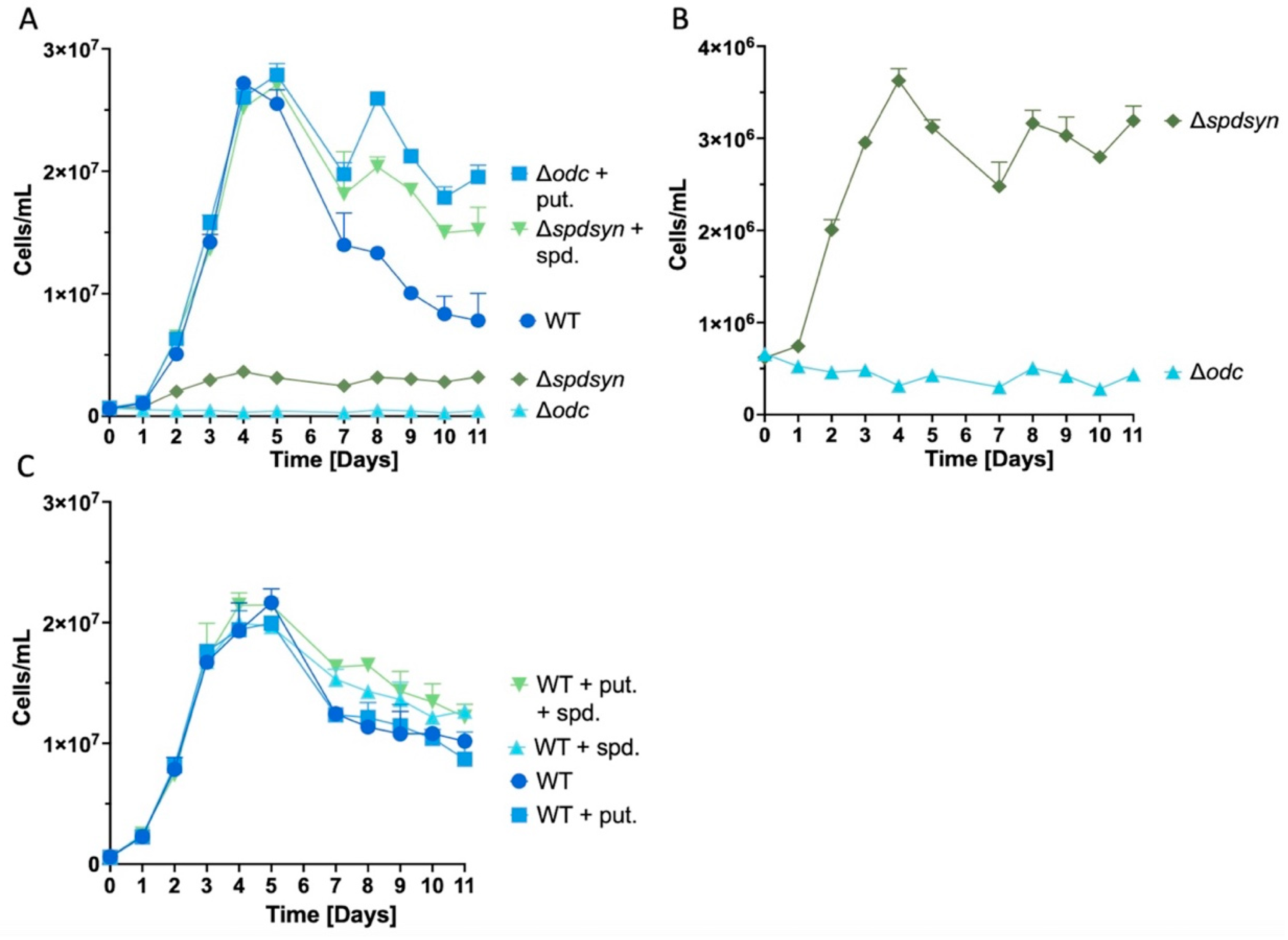

3.1. Extended Polyamine Starvation Exposes Distinct Growth Patterns in Parasites

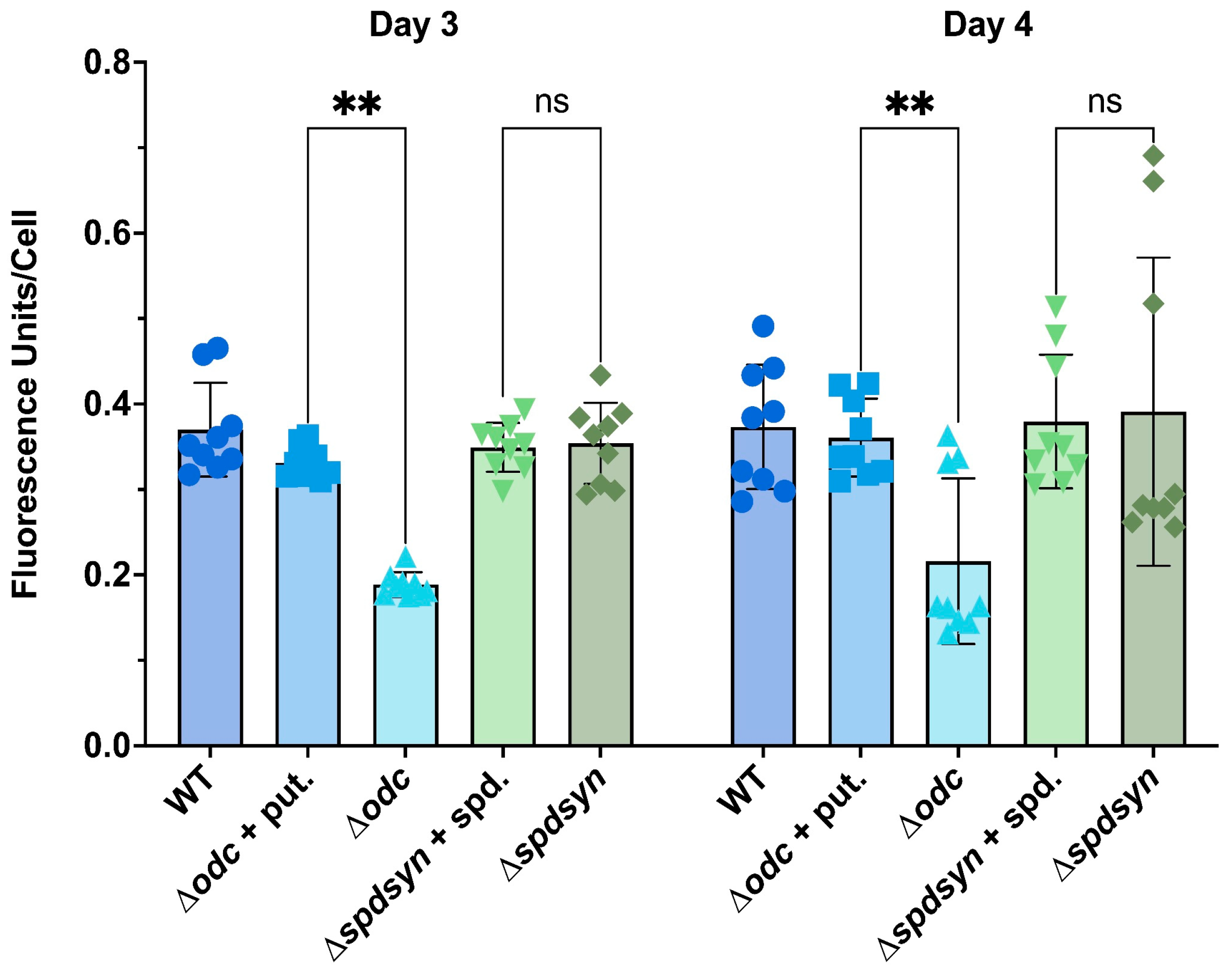

3.2. Putrescine is Essential for DNA Synthesis and Replication

3.3. Putrescine Depletion Reduces Metabolism

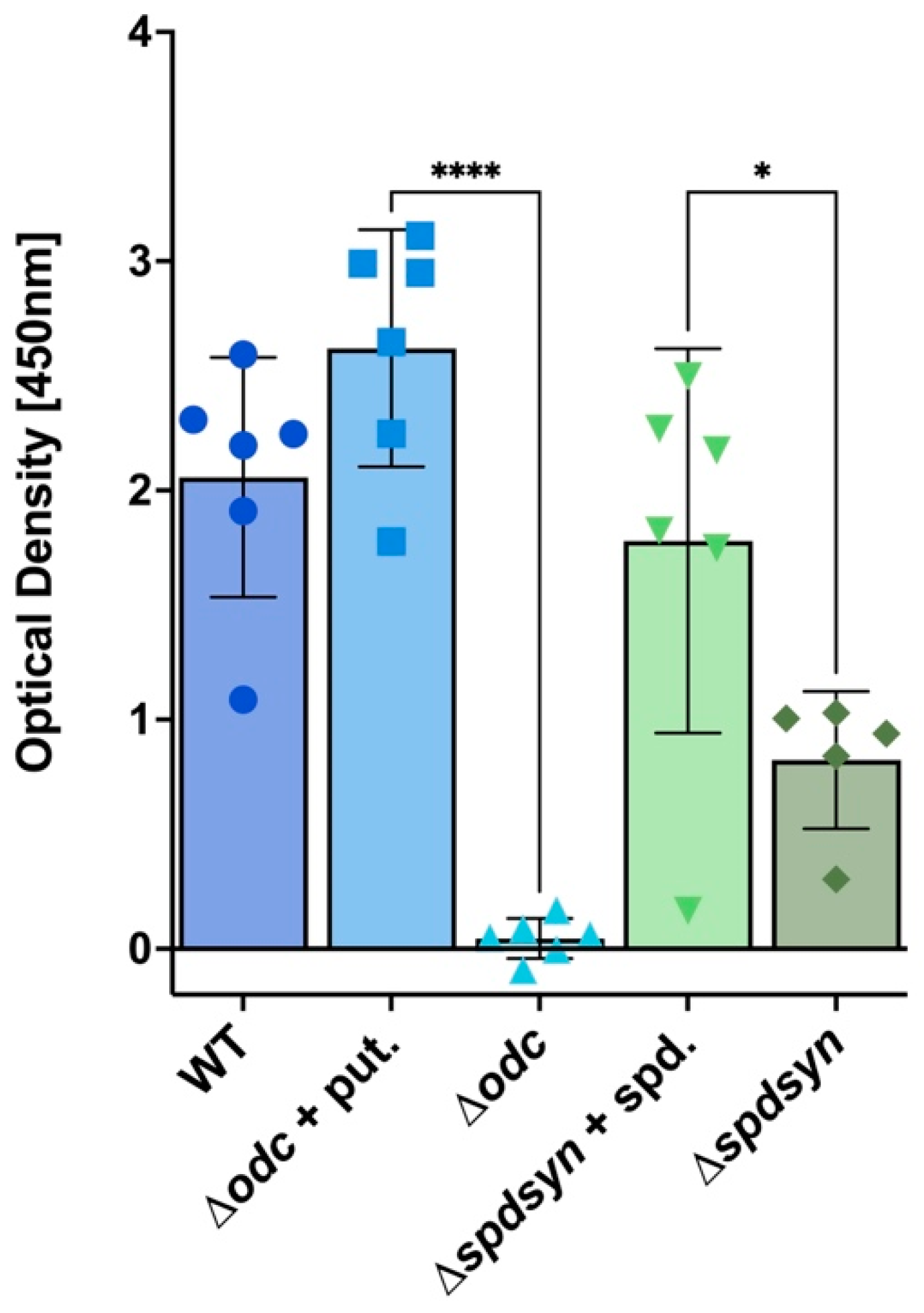

3.4. Polyamine Depletion Affects Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

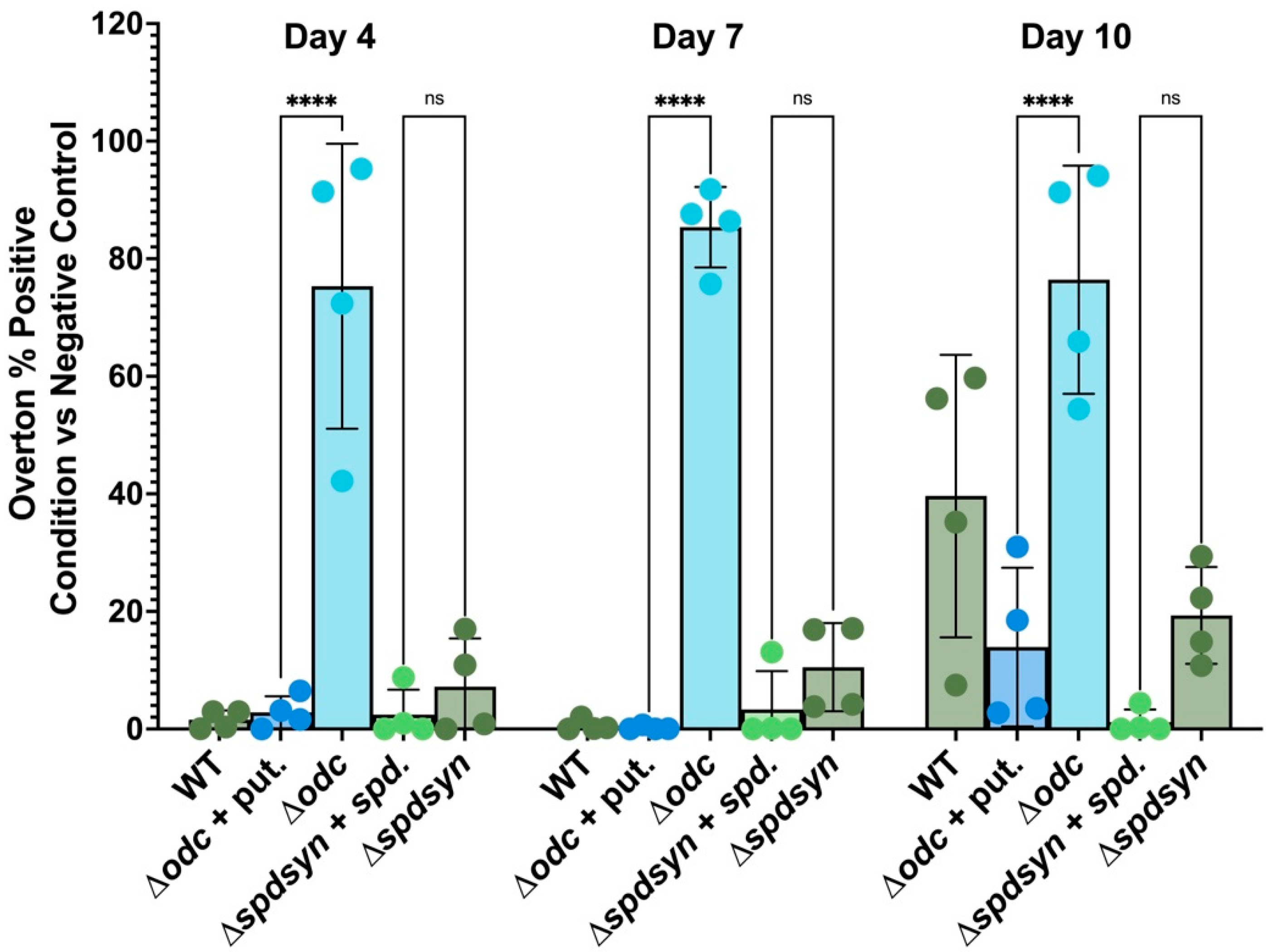

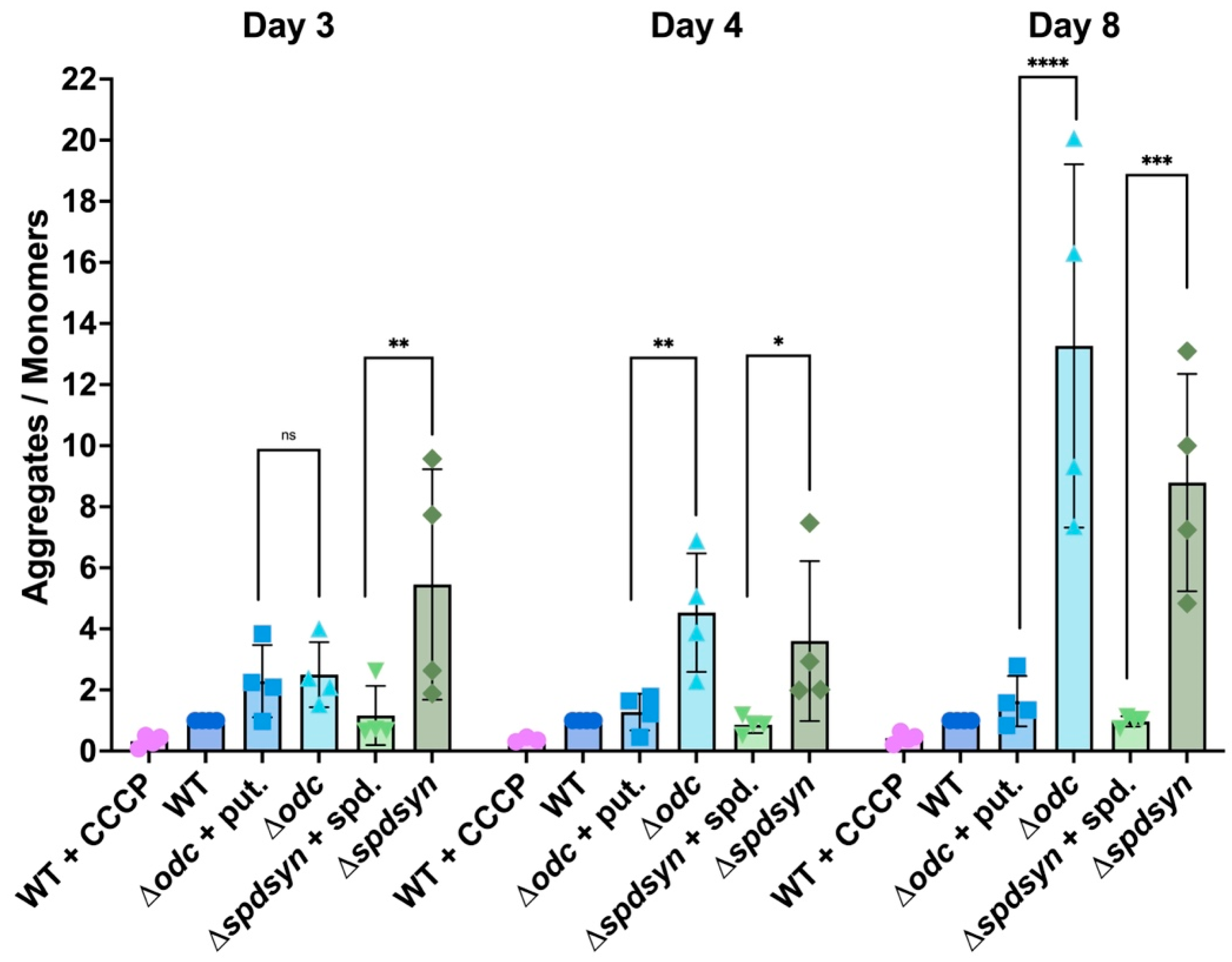

3.5. Putrescine Depletion triggers DNA Fragmentation

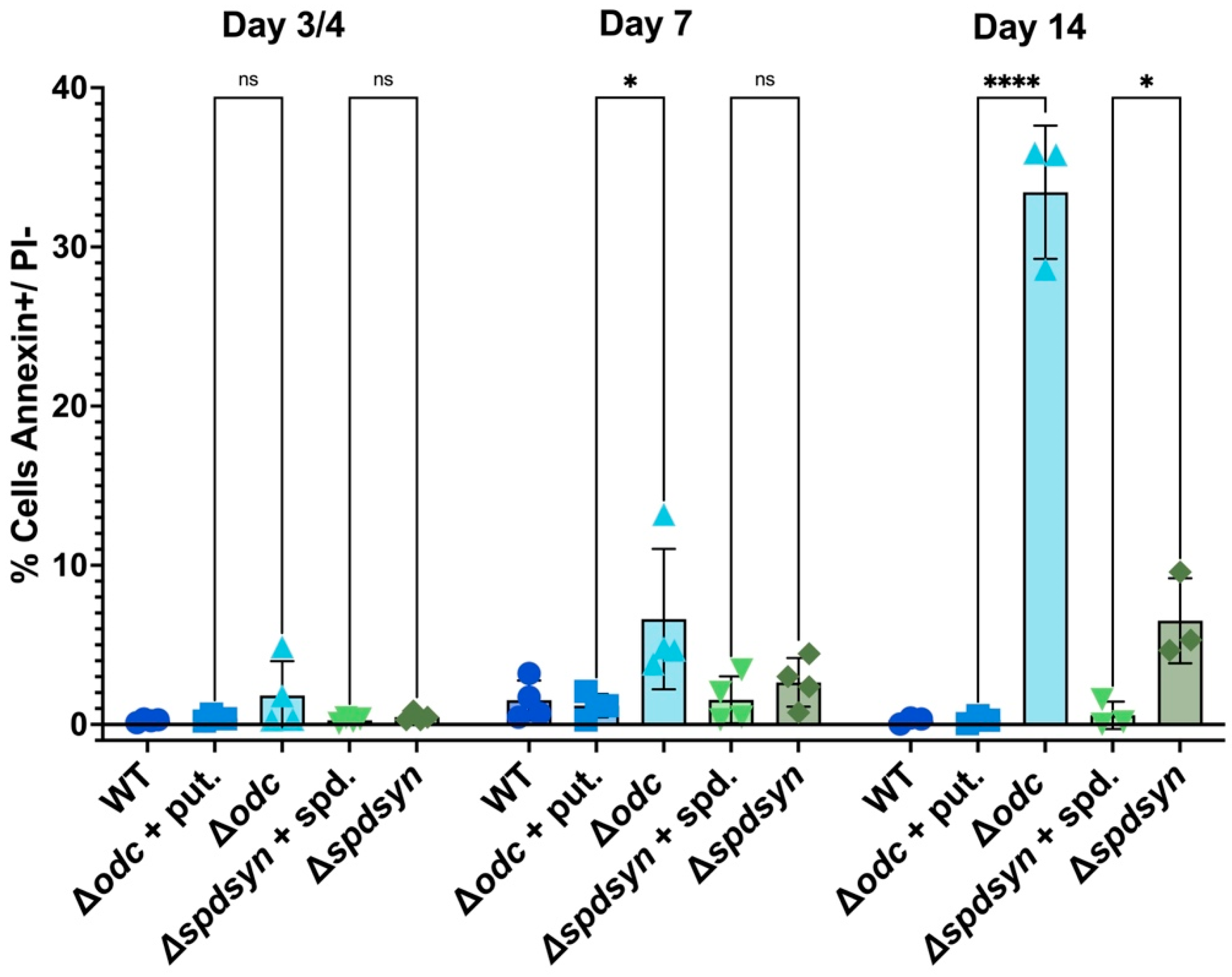

3.6. Polyamine Deprivation Causes Membrane Modifications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abate, M., Festa, A., Falco, M., Lombardi, A., Luce, A., Grimaldi, A., Zappavigna, S., Sperlongano, P., Irace, C., Caraglia, M., & Misso, G. (2020). Mitochondria as playmakers of apoptosis, autophagy and senescence. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 98, 139-153. [CrossRef]

- Abirami, M., Karan Kumar, B., Faheem, Dey, S., Johri, S., Reguera, R. M., Balana-Fouce, R., Gowri Chandra Sekhar, K. V., & Sankaranarayanan, M. (2023). Molecular-level strategic goals and repressors in Leishmaniasis - Integrated data to accelerate target-based heterocyclic scaffolds. Eur J Med Chem, 257, 115471. [CrossRef]

- Al-Habsi, M., Chamoto, K., Matsumoto, K., Nomura, N., Zhang, B., Sugiura, Y., Sonomura, K., Maharani, A., Nakajima, Y., Wu, Y., Nomura, Y., Menzies, R., Tajima, M., Kitaoka, K., Haku, Y., Delghandi, S., Yurimoto, K., Matsuda, F., Iwata, S., … Honjo, T. (2022). Spermidine activates mitochondrial trifunctional protein and improves antitumor immunity in mice. Science, 378(6618), eabj3510. [CrossRef]

- Alvar, J., Yactayo, S., & Bern, C. (2006). Leishmaniasis and poverty. Trends Parasitol, 22(12), 552-557. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Rodriguez, A., Jin, B. K., Radwanska, M., & Magez, S. (2022). Recent progress in diagnosis and treatment of Human African Trypanosomiasis has made the elimination of this disease a realistic target by 2030. Front Med (Lausanne), 9, 1037094. [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, N., Blas-Garcia, A., & Esplugues, J. V. (2011). Mitochondria sentencing about cellular life and death: a matter of oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Des, 17(36), 4047-4060. [CrossRef]

- Balana-Fouce, R., Ordonez, D., & Alunda, J. M. (1989). Putrescine transport system in Leishmania infantum promastigotes. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 35(1), 43-50. [CrossRef]

- Bamorovat, M., Sharifi, I., Khosravi, A., Aflatoonian, M. R., Agha Kuchak Afshari, S., Salarkia, E., Sharifi, F., Aflatoonian, B., Gharachorloo, F., Khamesipour, A., Mohebali, M., Zamani, O., Shirzadi, M. R., & Gouya, M. M. (2024). Global Dilemma and Needs Assessment Toward Achieving Sustainable Development Goals in Controlling Leishmaniasis. J Epidemiol Glob Health, 14(1), 22-34. [CrossRef]

- Barba-Aliaga, M., & Alepuz, P. (2022). Role of eIF5A in Mitochondrial Function. Int J Mol Sci, 23(3). [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M. P., Kyle, D. E., Sibley, L. D., Radke, J. B., & Tarleton, R. L. (2019). Protozoan persister-like cells and drug treatment failure. Nat Rev Microbiol, 17(10), 607-620. [CrossRef]

- Basmaciyan, L., & Casanova, M. (2019). Cell death in Leishmania. Parasite, 26, 71. (La mort cellulaire chez Leishmania.). [CrossRef]

- Basselin, M., Coombs, G. H., & Barrett, M. P. (2000). Putrescine and spermidine transport in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 109(1), 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Boitz, J. M., Gilroy, C. A., Olenyik, T. D., Paradis, D., Perdeh, J., Dearman, K., Davis, M. J., Yates, P. A., Li, Y., Riscoe, M. K., Ullman, B., & Roberts, S. C. (2017). Arginase Is Essential for Survival of Leishmania donovani Promastigotes but Not Intracellular Amastigotes. Infect Immun, 85(1). [CrossRef]

- Boitz, J. M., Yates, P. A., Kline, C., Gaur, U., Wilson, M. E., Ullman, B., & Roberts, S. C. (2009). Leishmania donovani ornithine decarboxylase is indispensable for parasite survival in the mammalian host. Infect Immun, 77(2), 756-763. [CrossRef]

- Burza, S., Croft, S. L., & Boelaert, M. (2018). Leishmaniasis. Lancet, 392(10151), 951-970. [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. S., Kawasaki, Y., Nahata, S. S., Elikaee, S., Rajab, S., Salam, L., Alabdulal, M. Y., Broessel, K. K., Foroghi, F., Abbas, A., Poormohamadian, R., & Roberts, S. C. (2022). Polyamine Metabolism in Leishmania Parasites: A Promising Therapeutic Target. Med Sci (Basel), 10(2). [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. S., Stamper, B. D., Elbarbry, F., Nguyen, V., Lopez, S., Kawasaki, Y., Poormohamadian, R., & Roberts, S. C. (2021). Natural Products That Target the Arginase in Leishmania Parasites Hold Therapeutic Promise. Microorganisms, 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Cecilio, P., Perez-Cabezas, B., Santarem, N., Maciel, J., Rodrigues, V., & Cordeiro da Silva, A. (2014). Deception and manipulation: the arms of leishmania, a successful parasite. Front Immunol, 5, 480. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, B., Jhingran, A., Singh, S., Tyagi, N., Park, M. H., Srinivasan, N., Roberts, S. C., & Madhubala, R. (2010). Identification and characterization of a novel deoxyhypusine synthase in Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem, 285(1), 453-463. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, B., Kumar, R. R., Tyagi, N., Subramanian, G., Srinivasan, N., Park, M. H., & Madhubala, R. (2012). A unique modification of the eukaryotic initiation factor 5A shows the presence of the complete hypusine pathway in Leishmania donovani. PLoS One, 7(3), e33138. [CrossRef]

- Corral, M. J., Gonzalez, E., Cuquerella, M., & Alunda, J. M. (2013). Improvement of 96-well microplate assay for estimation of cell growth and inhibition of Leishmania with Alamar Blue. J Microbiol Methods, 94(2), 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Cossarizza, A., Baccarani-Contri, M., Kalashnikova, G., & Franceschi, C. (1993). A new method for the cytofluorimetric analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential using the J-aggregate forming lipophilic cation 5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 197(1), 40-45. [CrossRef]

- Curtin, J. M., & Aronson, N. E. (2021). Leishmaniasis in the United States: Emerging Issues in a Region of Low Endemicity. Microorganisms, 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Das, M., Kumar, R., & Dubey, V. K. (2015). Ornithine decarboxylase of Leishmania donovani: biochemical properties and possible role of N-terminal extension. Protein Pept Lett, 22(2), 130-136. [CrossRef]

- Das, M., Singh, S., & Dubey, V. K. (2016). Novel Inhibitors of Ornithine Decarboxylase of Leishmania Parasite (LdODC): The Parasite Resists LdODC Inhibition by Overexpression of Spermidine Synthase. Chem Biol Drug Des, 87(3), 352-360. [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, L., Van Acker, S. I., Nicolaes, Y., Cunha, J. L. R., Ahmad, R., Hendrickx, R., Caljon, B., Imamura, H., Ebo, D. G., Jeffares, D. C., Sterckx, Y. G., Maes, L., Hendrickx, S., & Caljon, G. (2024). Long-term hematopoietic stem cells trigger quiescence in Leishmania parasites. PLoS Pathog, 20(4), e1012181. [CrossRef]

- Fairlamb, A. H. (1990). Trypanothione metabolism and rational approaches to drug design. Biochem Soc Trans, 18(5), 717-720. [CrossRef]

- Fairlamb, A. H., & Cerami, A. (1992). Metabolism and functions of trypanothione in the Kinetoplastida. Annu Rev Microbiol, 46, 695-729. [CrossRef]

- Fairley, L. H., Lejri, I., Grimm, A., & Eckert, A. (2023). Spermidine Rescues Bioenergetic and Mitophagy Deficits Induced by Disease-Associated Tau Protein. Int J Mol Sci, 24(6). [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, P. K., Oza, S. L., Fairlamb, A. H., & Hunter, W. N. (2008). Leishmania trypanothione synthetase-amidase structure reveals a basis for regulation of conflicting synthetic and hydrolytic activities. J Biol Chem, 283(25), 17672-17680. [CrossRef]

- Gannavaram, S., & Debrabant, A. (2012). Programmed cell death in Leishmania: biochemical evidence and role in parasite infectivity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2, 95. [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, C., Olenyik, T., Roberts, S. C., & Ullman, B. (2011). Spermidine synthase is required for virulence of Leishmania donovani. Infect Immun, 79(7), 2764-2769. [CrossRef]

- Goyard, S., Segawa, H., Gordon, J., Showalter, M., Duncan, R., Turco, S. J., & Beverley, S. M. (2003). An in vitro system for developmental and genetic studies of Leishmania donovani phosphoglycans. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 130(1), 31-42. [CrossRef]

- Gradoni, L., Iorio, M. A., Gramiccia, M., & Orsini, S. (1989). In vivo effect of eflornithine (DFMO) and some related compounds on Leishmania infantum preliminary communication. Farmaco, 44(12), 1157-1166. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2517472.

- Grifferty, G., Shirley, H., McGloin, J., Kahn, J., Orriols, A., & Wamai, R. (2021). Vulnerabilities to and the Socioeconomic and Psychosocial Impacts of the Leishmaniases: A Review. Res Rep Trop Med, 12, 135-151. [CrossRef]

- Grover, A., Katiyar, S. P., Jeyakanthan, J., Dubey, V. K., & Sundar, D. (2012). Mechanistic insights into the dual inhibition strategy for checking Leishmaniasis. J Biomol Struct Dyn, 30(4), 474-487. [CrossRef]

- Hasne, M. P., & Ullman, B. (2011). Genetic and biochemical analysis of protozoal polyamine transporters. Methods Mol Biol, 720, 309-326. [CrossRef]

- Hazra, S., Ghosh, S., Das Sarma, M., Sharma, S., Das, M., Saudagar, P., Prajapati, V. K., Dubey, V. K., Sundar, S., & Hazra, B. (2013). Evaluation of a diospyrin derivative as antileishmanial agent and potential modulator of ornithine decarboxylase of Leishmania donovani. Exp Parasitol, 135(2), 407-413. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J., Ortiz, J. F., Fabara, S. P., Eissa-Garces, A., Reddy, D., Collins, K. D., & Tirupathi, R. (2021). Efficacy and Toxicity of Fexinidazole and Nifurtimox Plus Eflornithine in the Treatment of African Trypanosomiasis: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 13(8), e16881. [CrossRef]

- Hotez, P. J. (2018). The rise of leishmaniasis in the twenty-first century. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 112(9), 421-422. [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, K., & Kashiwagi, K. (2010). Modulation of cellular function by polyamines. Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 42(1), 39-51. [CrossRef]

- Ikeogu, N. M., Akaluka, G. N., Edechi, C. A., Salako, E. S., Onyilagha, C., Barazandeh, A. F., & Uzonna, J. E. (2020). Leishmania Immunity: Advancing Immunotherapy and Vaccine Development. Microorganisms, 8(8). [CrossRef]

- Iovannisci, D. M., & Ullman, B. (1983). High efficiency plating method for Leishmania promastigotes in semidefined or completely-defined medium. J Parasitol, 69(4), 633-636. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6631633.

- Jara, M., Arevalo, J., Llanos-Cuentas, A., den Broeck, F. V., Domagalska, M. A., & Dujardin, J. C. (2023). Unveiling drug-tolerant and persister-like cells in Leishmania braziliensis lines derived from patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 13, 1253033. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Roberts, S. C., Jardim, A., Carter, N. S., Shih, S., Ariyanayagam, M., Fairlamb, A. H., & Ullman, B. (1999). Ornithine decarboxylase gene deletion mutants of Leishmania donovani. J Biol Chem, 274(6), 3781-3788. [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Ruiz, A., Alzate, J. F., Macleod, E. T., Luder, C. G., Fasel, N., & Hurd, H. (2010). Apoptotic markers in protozoan parasites. Parasit Vectors, 3, 104. [CrossRef]

- Kaczanowski, S., Sajid, M., & Reece, S. E. (2011). Evolution of apoptosis-like programmed cell death in unicellular protozoan parasites. Parasit Vectors, 4, 44. [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, M., & Tekwani, B. L. (1997). Polyamine transport systems of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Life Sci, 60(20), 1793-1801. [CrossRef]

- Kropf, P., Fuentes, J. M., Fahnrich, E., Arpa, L., Herath, S., Weber, V., Soler, G., Celada, A., Modolell, M., & Muller, I. (2005). Arginase and polyamine synthesis are key factors in the regulation of experimental leishmaniasis in vivo. FASEB J, 19(8), 1000-1002. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D., Perveen, S., Sharma, R., & Singh, K. (2021). Advancement in leishmaniasis diagnosis and therapeutics: An update. Eur J Pharmacol, 910, 174436. [CrossRef]

- Le Pape, P. (2008). Development of new antileishmanial drugs--current knowledge and future prospects. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem, 23(5), 708-718. [CrossRef]

- Li, W., & Sauve, A. A. (2015). NAD(+) content and its role in mitochondria. Methods Mol Biol, 1241, 39-48. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., Piao, C., Beuschel, C. B., Toppe, D., Kollipara, L., Bogdanow, B., Maglione, M., Lutzkendorf, J., See, J. C. K., Huang, S., Conrad, T. O. F., Kintscher, U., Madeo, F., Liu, F., Sickmann, A., & Sigrist, S. J. (2021). eIF5A hypusination, boosted by dietary spermidine, protects from premature brain aging and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Rep, 35(2), 108941. [CrossRef]

- Lodi, L., Voarino, M., Stocco, S., Ricci, S., Azzari, C., Galli, L., & Chiappini, E. (2024). Immune response to viscerotropic Leishmania: a comprehensive review. Front Immunol, 15, 1402539. [CrossRef]

- LoGiudice, N., Le, L., Abuan, I., Leizorek, Y., & Roberts, S. C. (2018). Alpha-Difluoromethylornithine, an Irreversible Inhibitor of Polyamine Biosynthesis, as a Therapeutic Strategy against Hyperproliferative and Infectious Diseases. Med Sci (Basel), 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Mandell, M. A., & Beverley, S. M. (2017). Continual renewal and replication of persistent Leishmania major parasites in concomitantly immune hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 114(5), E801-E810. [CrossRef]

- Mann, S., Frasca, K., Scherrer, S., Henao-Martinez, A. F., Newman, S., Ramanan, P., & Suarez, J. A. (2021). A Review of Leishmaniasis: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Curr Trop Med Rep, 8(2), 121-132. [CrossRef]

- Mathison, B. A., & Bradley, B. T. (2023). Review of the Clinical Presentation, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Lab Med, 54(4), 363-371. [CrossRef]

- McIlwee, B. E., Weis, S. E., & Hosler, G. A. (2018). Incidence of Endemic Human Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol, 154(9), 1032-1039. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A., & Shaha, C. (2004). Apoptotic death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes in response to respiratory chain inhibition: complex II inhibition results in increased pentamidine cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem, 279(12), 11798-11813. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, D., Valentim, C., Oliveira, M. F., & Vannier-Santos, M. A. (2006). Putrescine analogue cytotoxicity against Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol Res, 98(2), 99-105. [CrossRef]

- Menna-Barreto, R. F. S. (2019). Cell death pathways in pathogenic trypanosomatids: lessons of (over)kill. Cell Death Dis, 10(2), 93. [CrossRef]

- Mikus, J., & Steverding, D. (2000). A simple colorimetric method to screen drug cytotoxicity against Leishmania using the dye Alamar Blue. Parasitol Int, 48(3), 265-269. [CrossRef]

- Montaner-Angoiti, E., & Llobat, L. (2023). Is leishmaniasis the new emerging zoonosis in the world? Vet Res Commun, 47(4), 1777-1799. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. B., Das, M., Sudhandiran, G., & Shaha, C. (2002). Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels through the activation of non-selective cation channels induced by oxidative stress causes mitochondrial depolarization leading to apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. J Biol Chem, 277(27), 24717-24727. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R., & Madhubala, R. (1993). Effect of a bis(benzyl)polyamine analogue, and DL-alpha-difluoromethylornithine on parasite suppression and cellular polyamine levels in golden hamster during Leishmania donovani infection. Pharmacol Res, 28(4), 359-365. [CrossRef]

- Muxel, S. M., Aoki, J. I., Fernandes, J. C. R., Laranjeira-Silva, M. F., Zampieri, R. A., Acuna, S. M., Muller, K. E., Vanderlinde, R. H., & Floeter-Winter, L. M. (2017). Arginine and Polyamines Fate in Leishmania Infection. Front Microbiol, 8, 2682. [CrossRef]

- akanishi, S., & Cleveland, J. L. (2021). Polyamine Homeostasis in Development and Disease. Med Sci (Basel), 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Nepal, B., McCormick-Baw, C., Patel, K., Firmani, S., & Wetzel, D. M. (2024). Cutaneous Leishmania mexicana infections in the United States: defining strains through endemic human pediatric cases in northern Texas. mSphere, 9(3), e0081423. [CrossRef]

- Olenyik, T., Gilroy, C., & Ullman, B. (2011). Oral putrescine restores virulence of ornithine decarboxylase-deficient Leishmania donovani in mice. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 176(2), 109-111. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W. H. (2023). Leishmaniasis. Retrieved 12.5. from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis.

- Pandey, R. K., Prajapati, P., Goyal, S., Grover, A., & Prajapati, V. K. (2016). Molecular Modeling and Virtual Screening Approach to Discover Potential Antileishmanial Inhibitors Against Ornithine Decarboxylase. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen, 19(10), 813-823. [CrossRef]

- Park, M. H., Lee, Y. B., & Joe, Y. A. (1997). Hypusine is essential for eukaryotic cell proliferation. Biol Signals, 6(3), 115-123. [CrossRef]

- Pedra-Rezende, Y., Bombaca, A. C. S., & Menna-Barreto, R. F. S. (2022). Is the mitochondrion a promising drug target in trypanosomatids? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, 117, e210379. [CrossRef]

- Pegg, A. E. (2009). Mammalian polyamine metabolism and function. IUBMB Life, 61(9), 880-894. [CrossRef]

- Perdeh, J., Berioso, B., Love, Q., LoGiudice, N., Le, T. L., Harrelson, J. P., & Roberts, S. C. (2020). Critical functions of the polyamine putrescine for proliferation and viability of Leishmania donovani parasites. Amino Acids, 52(2), 261-274. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K. D., Tamborlin, L., Meneguello, L., de Proenca, A. R., Almeida, I. C., Lourenco, R. F., & Luchessi, A. D. (2016). Alternative Start Codon Connects eIF5A to Mitochondria. J Cell Physiol, 231(12), 2682-2689. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Pertejo, Y., Garcia-Estrada, C., Martinez-Valladares, M., Murugesan, S., Reguera, R. M., & Balana-Fouce, R. (2024). Polyamine Metabolism for Drug Intervention in Trypanosomatids. Pathogens, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Pessenda, G., & da Silva, J. S. (2020). Arginase and its mechanisms in Leishmania persistence. Parasite Immunol, 42(7), e12722. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. A. (2018). Polyamines in protozoan pathogens. J Biol Chem, 293(48), 18746-18756. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S., Schwartz, R. A., Patil, A., Grabbe, S., & Goldust, M. (2022). Treatment options for leishmaniasis. Clin Exp Dermatol, 47(3), 516-521. [CrossRef]

- Proto, W. R., Coombs, G. H., & Mottram, J. C. (2013). Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental? Nat Rev Microbiol, 11(1), 58-66. [CrossRef]

- Reece, S. E., Pollitt, L. C., Colegrave, N., & Gardner, A. (2011). The meaning of death: evolution and ecology of apoptosis in protozoan parasites. PLoS Pathog, 7(12), e1002320. [CrossRef]

- Reers, M., Smiley, S. T., Mottola-Hartshorn, C., Chen, A., Lin, M., & Chen, L. B. (1995). Mitochondrial membrane potential monitored by JC-1 dye. Methods Enzymol, 260, 406-417. [CrossRef]

- Reers, M., Smith, T. W., & Chen, L. B. (1991). J-aggregate formation of a carbocyanine as a quantitative fluorescent indicator of membrane potential. Biochemistry, 30(18), 4480-4486. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S. C., Jiang, Y., Jardim, A., Carter, N. S., Heby, O., & Ullman, B. (2001). Genetic analysis of spermidine synthase from Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol, 115(2), 217-226. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I. A., Garcia, A. R., Paz, M. M., Grilo Junior, R. G. D., Amaral, A. C. F., & Pinheiro, A. S. (2022). Polyamine and Trypanothione Pathways as Targets for Novel Antileishmanial Drugs. In A. B. Vermelho & C. T. Supuran (Eds.), Antiprotozoal Drug Development and Delivery (pp. 143-180). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A., Ganguly, A., BoseDasgupta, S., Das, B. B., Pal, C., Jaisankar, P., & Majumder, H. K. (2008). Mitochondria-dependent reactive oxygen species-mediated programmed cell death induced by 3,3’-diindolylmethane through inhibition of F0F1-ATP synthase in unicellular protozoan parasite Leishmania donovani. Mol Pharmacol, 74(5), 1292-1307. [CrossRef]

- Roy, K., Ghosh, S., Karmakar, S., Mandal, P., Hussain, A., Dutta, A., & Pal, C. (2024). Inverse correlation between Leishmania-induced TLR1/2 and TGF-beta differentially regulates parasite persistence in bone marrow during the chronic phase of infection. Cytokine, 185, 156811. [CrossRef]

- Sagar, N. A., Tarafdar, S., Agarwal, S., Tarafdar, A., & Sharma, S. (2021). Polyamines: Functions, Metabolism, and Role in Human Disease Management. Med Sci (Basel), 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Saini, I., Joshi, J., & Kaur, S. (2024). Leishmania vaccine development: A comprehensive review. Cell Immunol, 399-400, 104826. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Silva, K. M., Camargo, P. G., & Bispo, M. L. F. (2022). Promising Molecular Targets Related to Polyamine Biosynthesis in Drug Discovery against Leishmaniasis. Med Chem, 19(1), 2-9. [CrossRef]

- Sasidharan, S., & Saudagar, P. (2021). Leishmaniasis: where are we and where are we heading? Parasitol Res, 120(5), 1541-1554. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S., Hofer, S. J., Zimmermann, A., Pechlaner, R., Dammbrueck, C., Pendl, T., Marcello, G. M., Pogatschnigg, V., Bergmann, M., Muller, M., Gschiel, V., Ristic, S., Tadic, J., Iwata, K., Richter, G., Farzi, A., Ucal, M., Schafer, U., Poglitsch, M., … Madeo, F. (2021). Dietary spermidine improves cognitive function. Cell Rep, 35(2), 108985. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, P., Namdeo, M., Devender, M., Anand, A., Kumar, K., Veronica, J., & Maurya, R. (2024). Polyamine-Enriched Exosomes from Leishmania donovani Drive Host Macrophage Polarization via Immunometabolism Reprogramming. ACS Infect Dis. [CrossRef]

- Sen, N., Das, B. B., Ganguly, A., Mukherjee, T., Tripathi, G., Bandyopadhyay, S., Rakshit, S., Sen, T., & Majumder, H. K. (2004). Camptothecin induced mitochondrial dysfunction leading to programmed cell death in unicellular hemoflagellate Leishmania donovani. Cell Death Differ, 11(8), 924-936. [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, S. Y., Ansari, W. A., Hassan, F., Faruqui, T., Khan, M. F., Akhter, Y., Khan, A. R., Siddiqui, M. A., Al-Khedhairy, A. A., & Nasibullah, M. (2023). Drug repositioning to discover novel ornithine decarboxylase inhibitors against visceral leishmaniasis. J Mol Recognit, 36(7), e3021. [CrossRef]

- Smiley, S. T., Reers, M., Mottola-Hartshorn, C., Lin, M., Chen, A., Smith, T. W., Steele, G. D., Jr., & Chen, L. B. (1991). Intracellular heterogeneity in mitochondrial membrane potentials revealed by a J-aggregate-forming lipophilic cation JC-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 88(9), 3671-3675. [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Brown, E., & Hurd, H. (2013). The first suicides: a legacy inherited by parasitic protozoans from prokaryote ancestors. Parasit Vectors, 6, 108. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Guerrero, E., Quintanilla-Cedillo, M. R., Ruiz-Esmenjaud, J., & Arenas, R. (2017). Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000Res, 6, 750. [CrossRef]

- Vannier-Santos, M. A., Menezes, D., Oliveira, M. F., & de Mello, F. G. (2008). The putrescine analogue 1,4-diamino-2-butanone affects polyamine synthesis, transport, ultrastructure and intracellular survival in Leishmania amazonensis. Microbiology (Reading), 154(Pt 10), 3104-3111. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, H. M. (2009). The polyamines: past, present and future. Essays Biochem, 46, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Weingartner, A., Kemmer, G., Muller, F. D., Zampieri, R. A., Gonzaga dos Santos, M., Schiller, J., & Pomorski, T. G. (2012). Leishmania promastigotes lack phosphatidylserine but bind annexin V upon permeabilization or miltefosine treatment. PLoS One, 7(8), e42070. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, M., Gu, X., Li, J., Huang, D., Xue, C., & He, Y. (2023). Polyamines: their significance for maintaining health and contributing to diseases. Cell Commun Signal, 21(1), 348. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Sauve, A. A. (2021). Assays for Determination of Cellular and Mitochondrial NAD(+) and NADH Content. Methods Mol Biol, 2310, 271-285. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A., Hofer, S. J., & Madeo, F. (2023). Molecular targets of spermidine: implications for cancer suppression. Cell Stress, 7(7), 50-58. [CrossRef]

| Day | Cell Line | Apoptotic (AnnexinV+/ PI-) | Live (AnnexinV-/ PI-) |

Late Apoptosis / Necrotic (AnnexinV+/ PI+) |

Necrotic (AnnexinV-/ PI+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3-4 | WT | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 96.78 ± 1.85 | 1.56 ± 0.62 | 1.43 ± 1.31 |

| Δodc + put. | 0.4 ± 0.16 | 97.48 ± 0.49 | 1.26 ± 0.64 | 0.9 ± 0.28 | |

| Δodc | 1.82 ± 1.87 | 88.28 ± 9.81 | 6.73 ± 7.61 | 3.19 ± 2.39 | |

| Δspdsyn + spd. | 0.26 ± 0.14 | 97.8 ± 0.64 | 1 ± 0.21 | 0.96 ± 0.59 | |

| Δspdsyn | 0.47 ± 0.23 | 96.13 ± 0.34 | 2.03 ± 0.73 | 1.38 ± 0.91 | |

| Day 7 | WT | 1.52 ± 1.08 | 77.1 ± 12.09 | 16.21 ± 10.54 | 5.19 ± 1.7 |

| Δodc + put. | 1.19 ± 0.63 | 68.73 ± 16.09 | 19.34 ± 9.03 | 10.79 ± 7.84 | |

| Δodc | 6.62 ± 3.82 | 74.6 ± 6.03 | 13.13 ± 3.05 | 5.69 ± 1.84 | |

| Δspdsyn + spd. | 1.55 ± 1.28 | 68.13 ± 15.75 | 24.7 ± 12.79 | 5.67 ± 3.94 | |

| Δspdsyn | 2.64 ± 1.32 | 82.23 ± 8.03 | 9.88 ± 7.82 | 5.27 ± 2.39 | |

| Day 14 | WT | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 0.19 ± 0.23 | 87.23 ± 7.64 | 12.33 ± 7.57 |

| Δodc + put. | 0.29 ± 0.2 | 4.39 ± 6.09 | 78.53 ± 13.96 | 16.75 ± 9.29 | |

| Δodc | 33.43 ± 3.42 | 15.68 ± 5.97 | 37.1 ± 11.8 | 13.75 ± 6.78 | |

| Δspdsyn + spd. | 0.58 ± 0.7 | 9.93 ± 13.91 | 79.3 ± 12.42 | 10.19 ± 2.51 | |

| Δspdsyn | 6.52 ± 2.18 | 72.73 ± 20.88 | 13.34 ± 13.06 | 7.45 ± 5.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).