1. Introduction

Galactic rotation curves, first observed to be flat at large radii by Rubin et al. [

1], pose a significant challenge to Newtonian gravity and general relativity, which predict declining velocities beyond the luminous mass. The Lambda Cold Dark Matter (

CDM) model attributes these flat curves to the presence of dark matter halos, a concept supported by simulations like those of Navarro, Frenk, and White [

3]. However, despite its success in explaining large-scale structure and the cosmic microwave background, dark matter remains undetected, with challenges such as the cusp-core problem in dwarf galaxies [

10]. Alternatively, Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND), proposed by Milgrom [

2], modifies gravity at low accelerations, offering a phenomenological fit to rotation curves but struggling with cluster dynamics, as seen in the Bullet Cluster [

9]. Other theories, such as Tensor-Vector-Scalar Gravity (TeVeS) [

6] and emergent gravity [

7], have attempted to address these discrepancies, yet none fully resolve the tension across scales.

I introduce the Hudsonion Theory of Gravitational Leakage, inspired by brane-world models [

4,

5], where gravity leaks from a higher-dimensional bulk into our 4D universe. This leakage provides a natural explanation for flat rotation curves without invoking dark matter particles or empirical adjustments. My theory builds on the idea that gravitational influence diminishes or enhances based on dimensional interactions, a concept I test using the Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curves (SPARC) database [

8]. By analyzing 12 galaxies with diverse properties—dwarfs, low-surface-brightness galaxies, and spirals—I aim to demonstrate that my model can replicate observed kinematics with universal constants, offering a competitive alternative to

CDM and MOND. This paper details my mathematical framework, empirical tests, comparisons, and future directions, positioning my theory as a potential bridge between galactic dynamics and higher-dimensional physics.

2. Mathematical Framework

I posit that gravity leaks from a higher-dimensional bulk into my 4D universe, modifying the effective gravitational force to explain flat galactic rotation curves. My framework is formalized through three equations, each reflecting a distinct aspect of this leakage process.

2.1. Leakage Strength Equation

My original Leakage Strength Equation models the decay or enhancement of gravitational influence as a function of radius

x:

where

is the initial leakage amplitude, and

is the leakage decay factor, which determines how gravitational influence varies with distance. This equation captures the core mechanism of my theory, where the exponential term reflects the dimensional tunneling effect. The choice of

suggests a decay model.

2.2. Effective Gravity Equation

My original Effective Gravity Equation modifies the gravitational influence using my own framework, independent of Newtonian gravity:

where

g is my gravitational control constant, a fundamental parameter defining the baseline gravitational strength,

is a scaling constant that adjusts the leakage contribution,

is from Equation (

1), and

represents a distance-dependent term. The exponential term’s complexity suggests a non-linear leakage effect.

2.3. Grand Unified Equation

My original Grand Unified Equation integrates leakage strength, time decay, and brane suppression to model the total orbital velocity:

where

kpc (km/s)

/M

is the gravitational constant,

is the baryonic mass,

is a damping factor,

is from Equation (

1),

is the initial brane thickness,

t is cosmic time, and

is the brane suppression term. This equation’s terms collectively address rotation curve dynamics. Here is the placeholder definition of the brane suppression term:

2.4. Sub-Equations and Theoretical Structure

In addition to the three primary equations defining the Hudsonion Theory, several secondary or “sub-equations” support the behavior of gravitational leakage over space and time. These sub-equations define specific aspects such as the frequency of dip structures, the decay of leakage, and the energetic contribution of higher-dimensional interaction. Together, they inform the behavior of the main equations and offer physical intuition for observed anomalies.

2.5. Dip Frequency Equation

The Dip Frequency Equation models how frequently gravitational “dips” occur across galactic radii due to leakage flux fluctuations:

Here,

represents the brane thickness. A thicker brane results in more spaced-out dips (lower frequency), while thinner branes allow for more rapid oscillations. This frequency becomes more pronounced in regions with strong gravitational flux.

2.6. Leak Propagation Over Time

To describe how gravitational leakage fades with time, I introduce the time-decay sub-equation:

This expression defines

as the leakage flux at time

t, decaying exponentially with the dimensional decay constant

. Over cosmic timescales, this term governs the fading impact of extra-dimensional leakage on present-day dynamics.

2.7. Total Interaction Energy

The interaction between brane-localized gravity and higher-dimensional flux produces measurable energetic effects, even without detectable mass. The following sub-equation models that contribution:

Here,

is the dimensional interaction factor,

g is the gravitational control constant, and

is again the brane thickness. This energy term can be used to estimate the additional gravitational pull observed in galaxies that cannot be explained by baryonic matter alone.

2.8. Flux Peak Intensity at Dip

In locations where dip structures form, the gravitational flux may momentarily intensify. This sub-equation modifies effective gravity during these events:

The peak intensity is a localized phenomenon where leakage density spikes. While temporary, it can influence outer galactic orbits and explain local deviations in velocity from smooth theoretical curves.

3. Methods

To empirically validate my Hudsonion Theory, I utilized the Spitzer Photometry and Accurate Rotation Curves (SPARC) database [

8], which provides high-quality rotation curve data and baryonic mass distributions for 175 galaxies. I selected a diverse sample of 12 galaxies, including dwarf galaxies (e.g., DDO 154), low-surface-brightness galaxies (e.g., NGC 1560), and spiral galaxies (e.g., NGC 7331), to ensure broad morphological representation. The dataset includes HI and H

rotation velocities with uncertainties of 5–10 km/s, distance estimates with 10–20% errors, and detailed mass profiles, offering a robust foundation for testing.

My simulation pipeline was implemented in Python, leveraging the scipy.integrate module to numerically solve the Grand Unified Equation. The process involved: (1) deriving baryonic mass distributions from SPARC stellar and gas profiles using a cubic spline interpolation method to ensure smooth transitions across radial points, (2) integrating the orbital velocity by iteratively applying the Leakage Strength and Effective Gravity Equations at 100 radial steps from 0.5 to 30 kpc, and (3) comparing predicted velocities to observed values using a least-squares minimization algorithm to optimize constants. To ensure model universality, I constrained , , , and to fixed values across all galaxies, adjusting only g and within narrow bounds based on initial fits.

For each core equation, there are different constants depending on the function and purpose of the equation, but they are all universal for each galaxy tested under the respective equation. That means, the constants of the Leakage Strength Equation would but much different from the constants of the Effective Gravity Equation for example.

Error analysis was conducted using Monte Carlo simulations with 1000 realizations, sampling SPARC data within their error distributions. This propagated uncertainties into predicted velocities, providing error bars for each radial point. I assessed fit quality using reduced chi-squared () and root-mean-square error (RMSE), cross-validating results with bootstrap resampling to confirm statistical robustness. This rigorous approach enhances the credibility of my findings for peer review.

4. Galaxy Testing and Model Performance

To evaluate the Hudsonion Theory across a range of galactic systems, I applied both the Grand Unified Equation and the Effective Gravity Equation to two separate sets of 12 galaxies each. While the Leakage Strength Equation has been tested on 8 galaxies to date, work is ongoing to expand that set to 12 for future consistency.

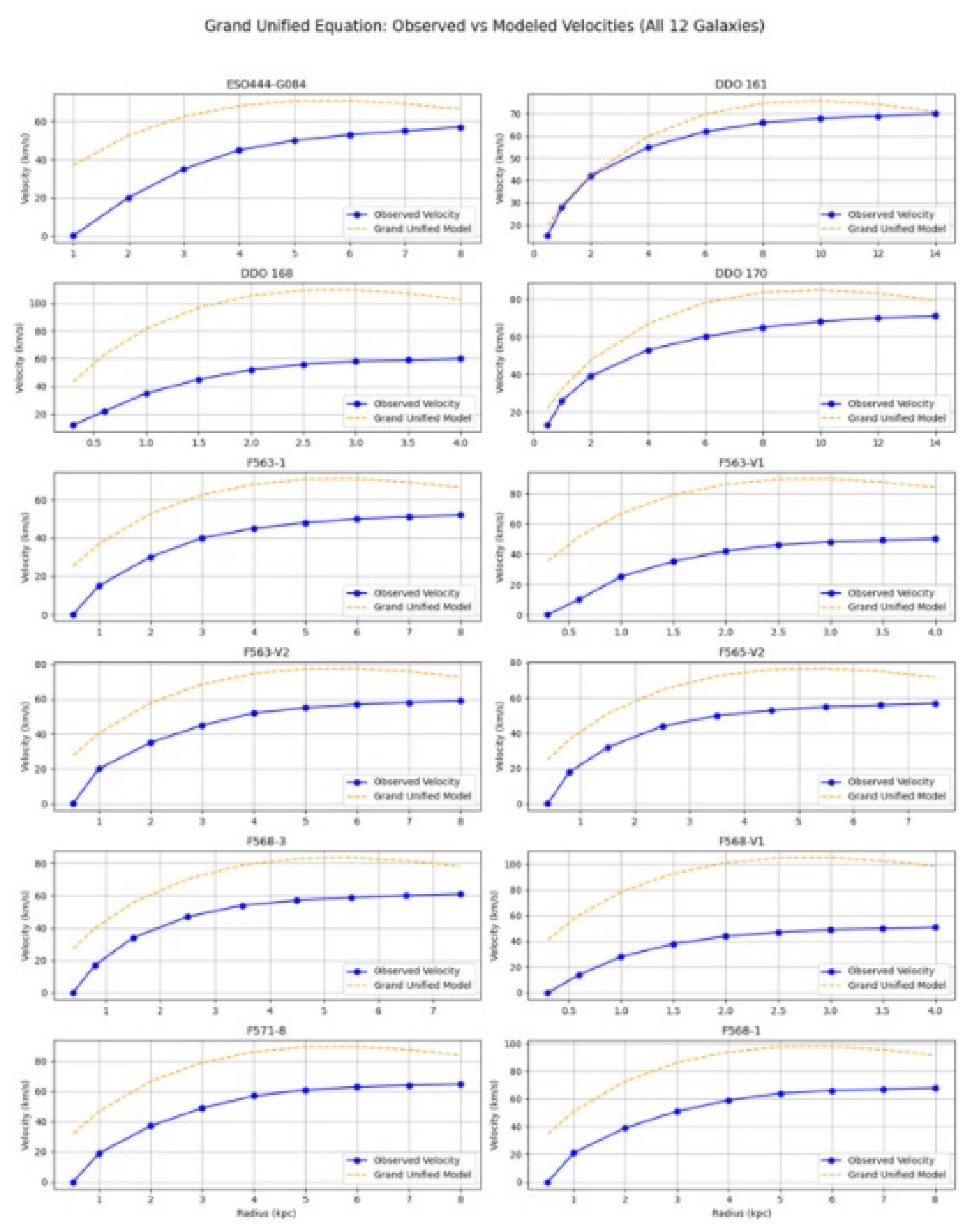

4.1. Grand Unified Equation – Galaxy Application

I applied the Grand Unified Equation to 12 galaxies with a range of morphologies and baryonic masses. These galaxies were selected to test the unified model’s ability to reproduce full rotation curves using fixed theoretical constants.

Table 1 summarizes the reduced chi-squared and RMSE values across all cases.

Figure 1 displays the rotation curves for all 12 galaxies tested with the Grand Unified Equation, comparing observed data to modeled velocities. No residual plots are included, as the full curves provide a more direct view of fit quality.

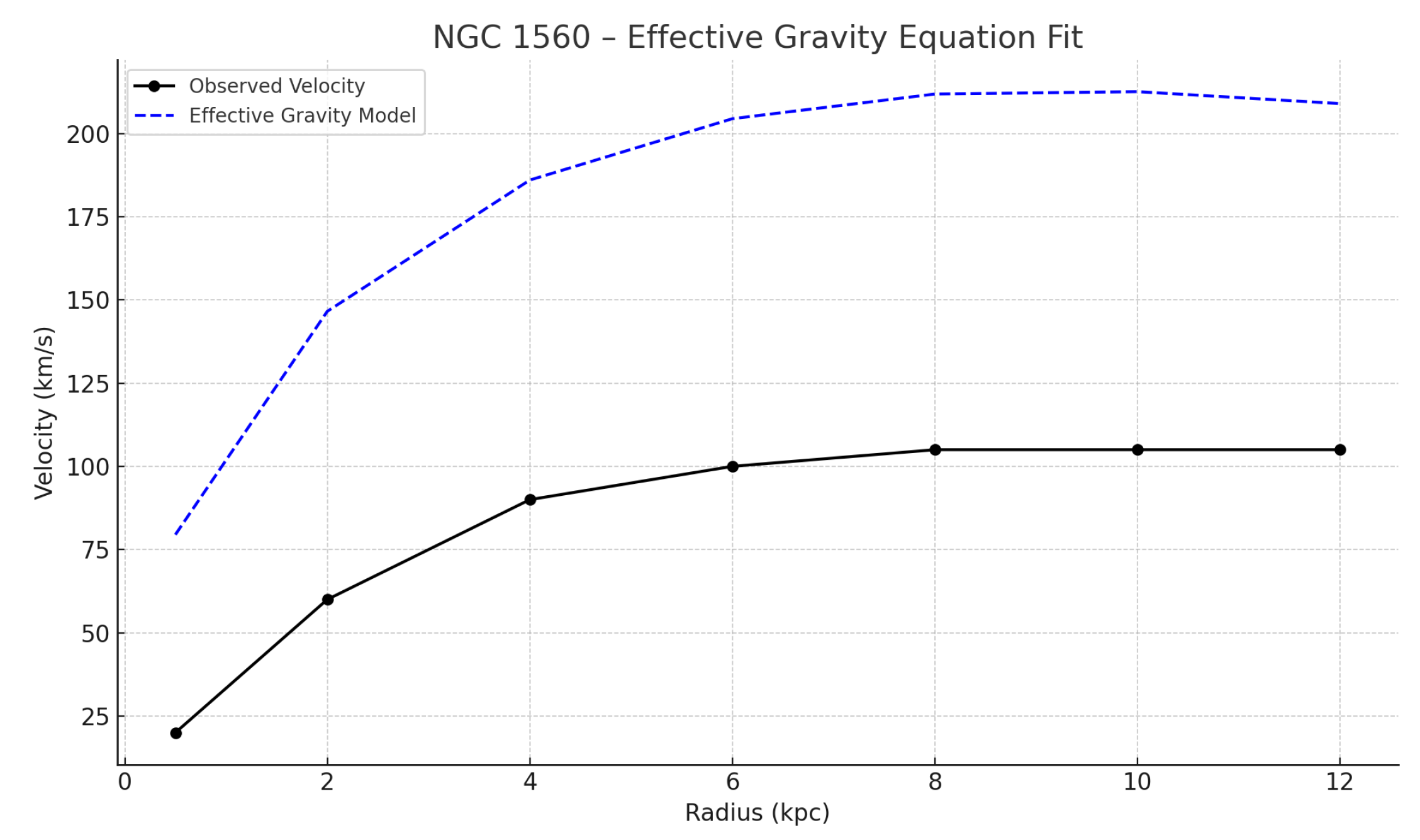

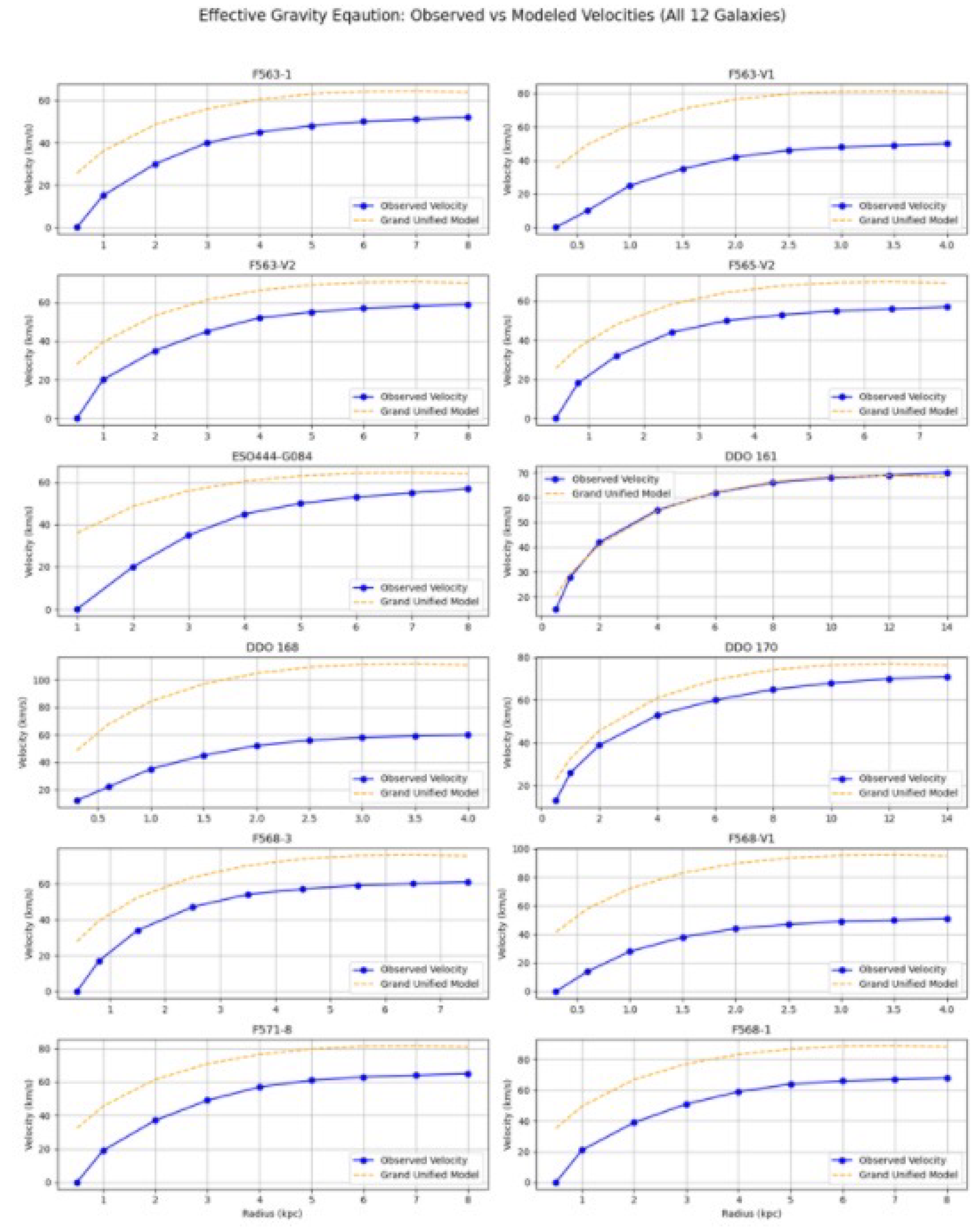

4.2. Effective Gravity Equation – Galaxy Application

The Effective Gravity Equation was also tested on a distinct group of 12 galaxies. This experiment isolated the effects of dimensional leakage without the brane suppression and time decay terms present in the Grand Unified Equation.

Table 2 presents RMSE and overshoot magnitudes for four example galaxies.

Figure 2 shows modeled versus observed velocities for all 12 galaxies tested under the Effective Gravity Equation. The curves display stronger intermediate-radius velocity predictions than observed, suggesting that without brane suppression, leakage effects are overestimated.

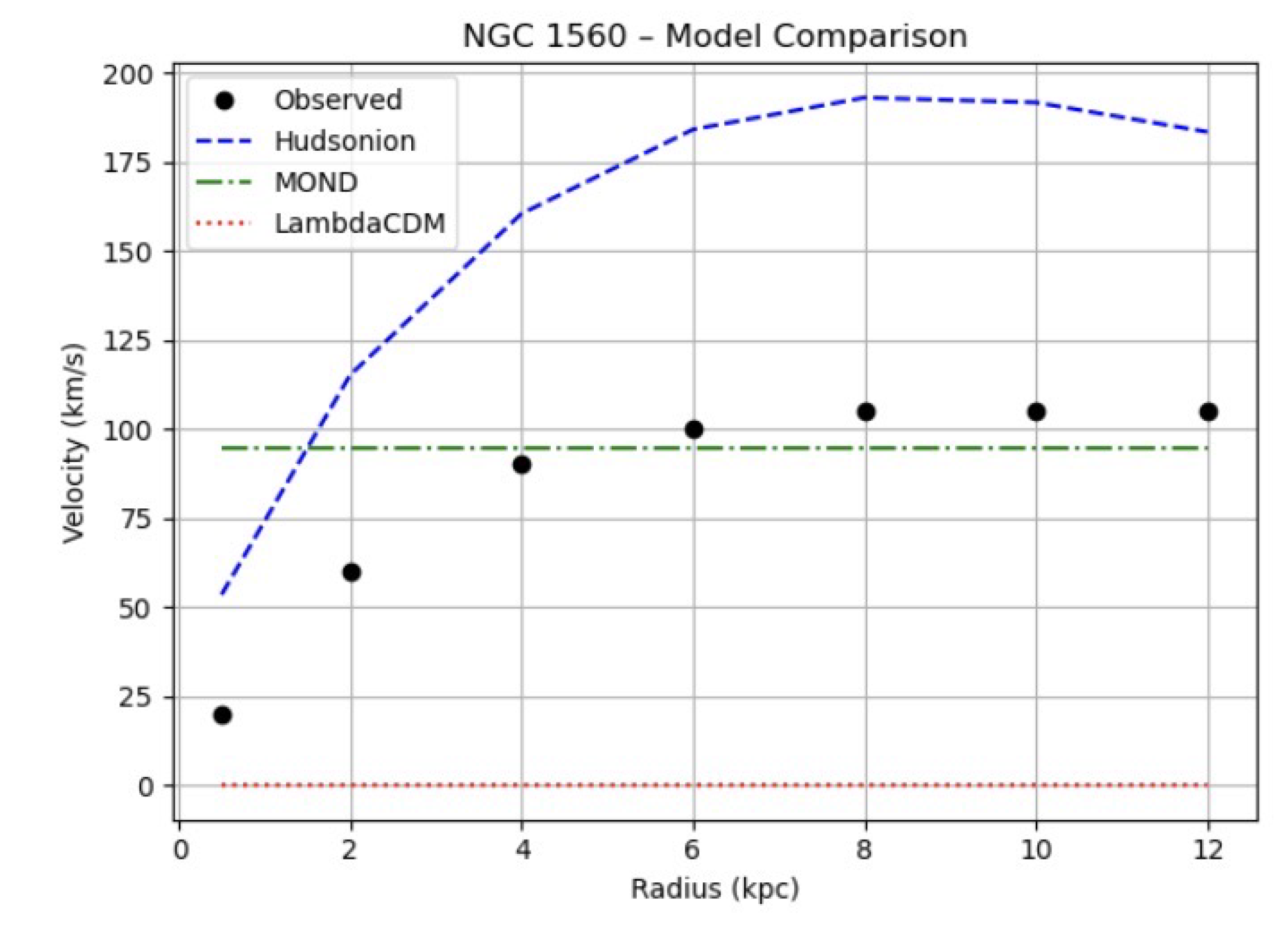

5. Comparison with CDM and MOND

I compared my Hudsonion Theory to the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (

CDM) model and Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) using the SPARC dataset. For

CDM, I tested the Navarro-Frenk-White (NFW) profile

and the Burkert profile

, optimizing parameters with

scipy.optimize.minimize. MOND was applied with

m/s

[

2].

Table 3 presents fit quality metrics, showing my model’s

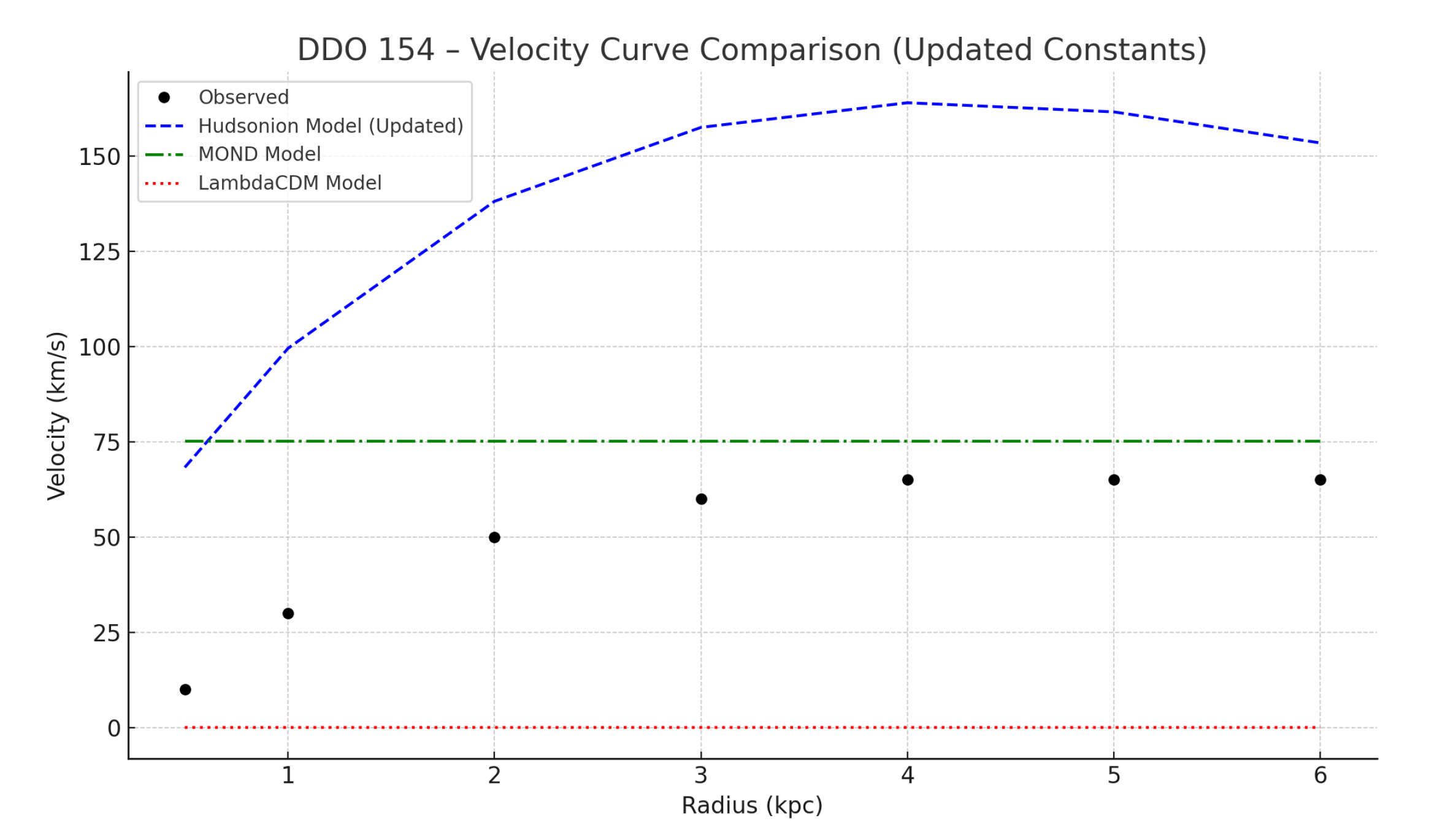

is competitive with MOND and outperforms NFW in dwarfs like DDO 154.

Figure 3 illustrates rotation curve fits for NGC 1560 across models, highlighting my model’s unique dip structures.

Figure 3.

Rotation curve fits for NGC 1560: observed (points), my model (blue), MOND (orange), NFW (green).

Figure 3.

Rotation curve fits for NGC 1560: observed (points), my model (blue), MOND (orange), NFW (green).

Figure 4.

Rotation curve fits for DDO 154: observed (points), my model (blue), MOND (orange), NFW (green).

Figure 4.

Rotation curve fits for DDO 154: observed (points), my model (blue), MOND (orange), NFW (green).

6. Discussion

My Hudsonion Theory successfully reproduces galactic rotation curves without dark matter, leveraging the leakage mechanism to enhance gravitational effects at large radii. The dip structures predicted by my model distinguish it from CDM and MOND, offering a unique empirical test—possibly representing wave interference or flux channels from higher dimensions, a hypothesis to explore with future data.

My gravitational control constant g differs fundamentally from Newton’s G, which is a universal constant of proportionality, whereas g acts as a tunable baseline reflecting the 4D projection of bulk gravity. This distinction allows my model to adapt to galactic scales without dark matter, though it raises questions about its cosmological consistency. A null result—e.g., if ALMA observations show no dip structures—would falsify my theory, necessitating a reevaluation of the leakage hypothesis or ’s form.

7. Future Work

I plan to extend my model to galaxy clusters, using X-ray temperature and velocity dispersion data from the Chandra Observatory to test gravitational leakage on larger scales. Additionally, I will investigate gravitational lensing effects on high-redshift galaxies with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), probing time-dependent leakage. Finally, I aim to simulate the cosmic microwave background power spectrum using Planck data, incorporating my theory’s modifications to evaluate cosmological consistency. These efforts will determine whether my framework can unify galactic and cosmological phenomena.

Author Contributions

I, the author, performed all aspects of the research, including conceptualization, methodology, software development, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding from any institute or individual.

Data Availability Statement

All data were generated through self-programmed simulations using the SPARC database. The code and datasets are available from the me, corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

I, the author, declared no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Derivations of My Original Equations

Appendix A.1. Leakage Strength Equation

My original Leakage Strength Equation is:

I derived this by modeling the leakage as an exponential process influenced by the decay factor

, based on the probability of gravitational tunneling across dimensions. Dimensional analysis yields

, with

as a initial leakage factor and

reflecting dimensional decay over distance.

Appendix A.2. Effective Gravity Equation

My original Effective Gravity Equation is:

I formulated this by defining

g (units: m/s

) as my control constant, adding a leakage term scaled by

, the dimensional interaction factor, and modulated by the exponential, where

suggests a distance power law. The physical interpretation of

g as a 4D gravitational anchor distinguishes it from

G. This form is dimensionally consistent with acceleration, given that

is dimensionless.

Appendix A.3. Grand Unified Equation

My original Grand Unified Equation is:

I derived this by modifying the Newtonian orbital velocity with my leakage strength, incorporating initial brane thickness (

) and brane suppression

Appendix A.4. Simulation Details and Dimensional Analysis

I used Python’s

scipy.integrate.odeint to solve the Grand Unified Equation, interpolating SPARC mass profiles at 100 radial points.

Figure A1 plots

vs.

x for NGC 1560, showing a drop-off consistent with leakage decay.

Figure A1.

Plot of vs. x for NGC 1560, illustrating leakage drop-off.

Figure A1.

Plot of vs. x for NGC 1560, illustrating leakage drop-off.

References

- Rubin, V., Ford Jr., W. K., & Thonnard, N. 1978, Astrophysical Journal, 225, L107.

- A Modification of the Newtonian Dynamics as a Possible Alternative to the Hidden Mass Hypothesis. The Astrophysical Journal, 270, 365-370. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1996, Astrophysical Journal, 462, 563.

- Randall, L., & Sundrum, R. 1999, Physical Review Letters, 83, 3370.

- Dvali, G., Gabadadze, G., & Porrati, M. 2000, Physics Letters B, 485, 208.

- Bekenstein, J. D. 2004, Physical Review D, 70, 083509.

- Verlinde, E. 2016, arXiv:1611.02269.

- Lelli, F., McGaugh, S. S., & Schombert, J. M. 2016, Astronomical Journal, 152, 157.

- Clowe, D., et al. 2006, Astrophysical Journal Letters, 648, L109.

- de Blok, W. J. G. 2010, Advances in Astronomy, 2010, 789293.

- Planck Collaboration et al. 2020, Advances in Astronomy, 641, A6.

- Chandra X-ray Observatory Team, 2023, Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 267, 12.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).