Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

We present a novel approach to the dark sector phenomena in cosmology and astrophysics—the Cosmic Gravitational Field (CGF) theory. This framework introduces a gravity amplification field that enhances the standard gravitational interaction without requiring dark matter. We demonstrate that a simplified version of this theory, referred to as the Simple CGF model, successfully explains galaxy rotation curves while maintaining connections to cosmological acceleration. Using rotation curve data from 20 galaxies, we perform a comprehensive statistical comparison between the Simple CGF model and the standard ΛCDM paradigm. Our analysis shows that the Simple CGF model provides statistically comparable fits to ΛCDM, as quantified by the Akaike Information Criterion, while requiring fewer free parameters. These results suggest that the CGF approach offers a compelling alternative to the standard cosmological model, providing a unified explanation for phenomena traditionally attributed to both dark matter and dark energy, while maintaining consistency with fundamental physical principles.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Philosophical Foundations

2.1. From Spacetime to Fields: A Paradigm Shift

2.2. The Active Nature of Gravity

2.3. Unification of Scales: Bridging Quantum and Cosmic Realms

2.4. Relational vs. Absolute Views of Spacetime

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Action Principle and Field Equations

Derivation of Field Equations

3.2. The Simple CGF Model Derivation

3.3. The Gravity Amplification Mechanism

3.4. Temporal Field Dynamics

4. Comparison with Other Theories

4.1. CGF vs. CDM

4.2. CGF vs. MOND/TeVeS

- Theoretical foundation: MOND is fundamentally a phenomenological model that modifies Newton’s second law, while CGF is derived from a relativistic action principle that modifies Einstein’s equations.

- Acceleration scale: MOND introduces a characteristic acceleration scale below which gravity behaves differently, whereas CGF introduces a length scale associated with the range of the gravity amplification field.

- Cosmological connections: TeVeS struggles to provide a consistent explanation for cosmic acceleration, while CGF naturally incorporates both galaxy-scale effects and cosmological acceleration through the dynamics of the scalar field.

4.3. CGF vs. Other Modified Gravity Approaches

- gravity: While theories modify the gravitational action by replacing the Ricci scalar R with a function , CGF introduces a dynamical scalar field that couples to R, providing more flexibility in addressing both galactic and cosmological phenomena.

- Scalar-Tensor-Vector Gravity: These theories introduce additional fields beyond the metric tensor, similar to CGF. However, CGF’s emphasis on the gravity amplification mechanism provides a clearer physical interpretation of how these additional fields modify gravity.

- Non-local gravity: Non-local modifications introduce non-local terms in the gravitational action, whereas CGF remains local, preserving conventional field theory principles while achieving similar phenomenological results.

5. Methodology

5.1. Data Sources

- Availability of high-quality rotation curve data

- Sufficient radial coverage to constrain the outer regions of the rotation curve

- Well-determined distance measurements

- Well-constrained inclination and position angles

- Extraction of rotation curves from moment maps

- Correction for inclination and asymmetric drift

- Conversion of angular distances to physical distances using the best available distance measurements

- Estimation of the baryonic mass distribution from stellar and gas observations

5.2. Model Implementation

5.2.1. Simple CGF Implementation

5.2.2. CDM Implementation

5.3. Statistical Analysis Framework

5.3.1. Parameter Estimation

5.3.2. Model Selection

5.3.3. Uncertainty Estimation

6. Results

6.1. Model Performance

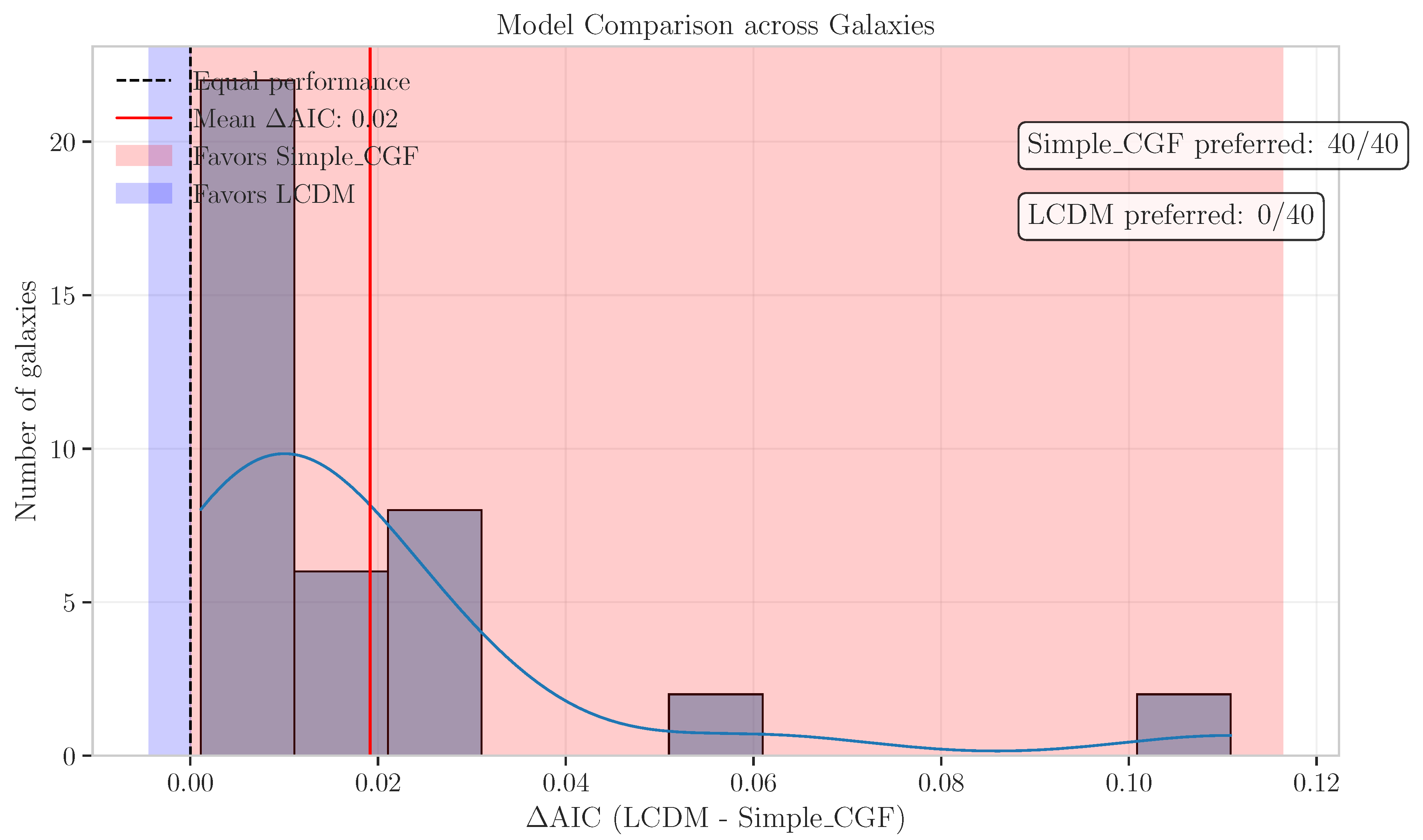

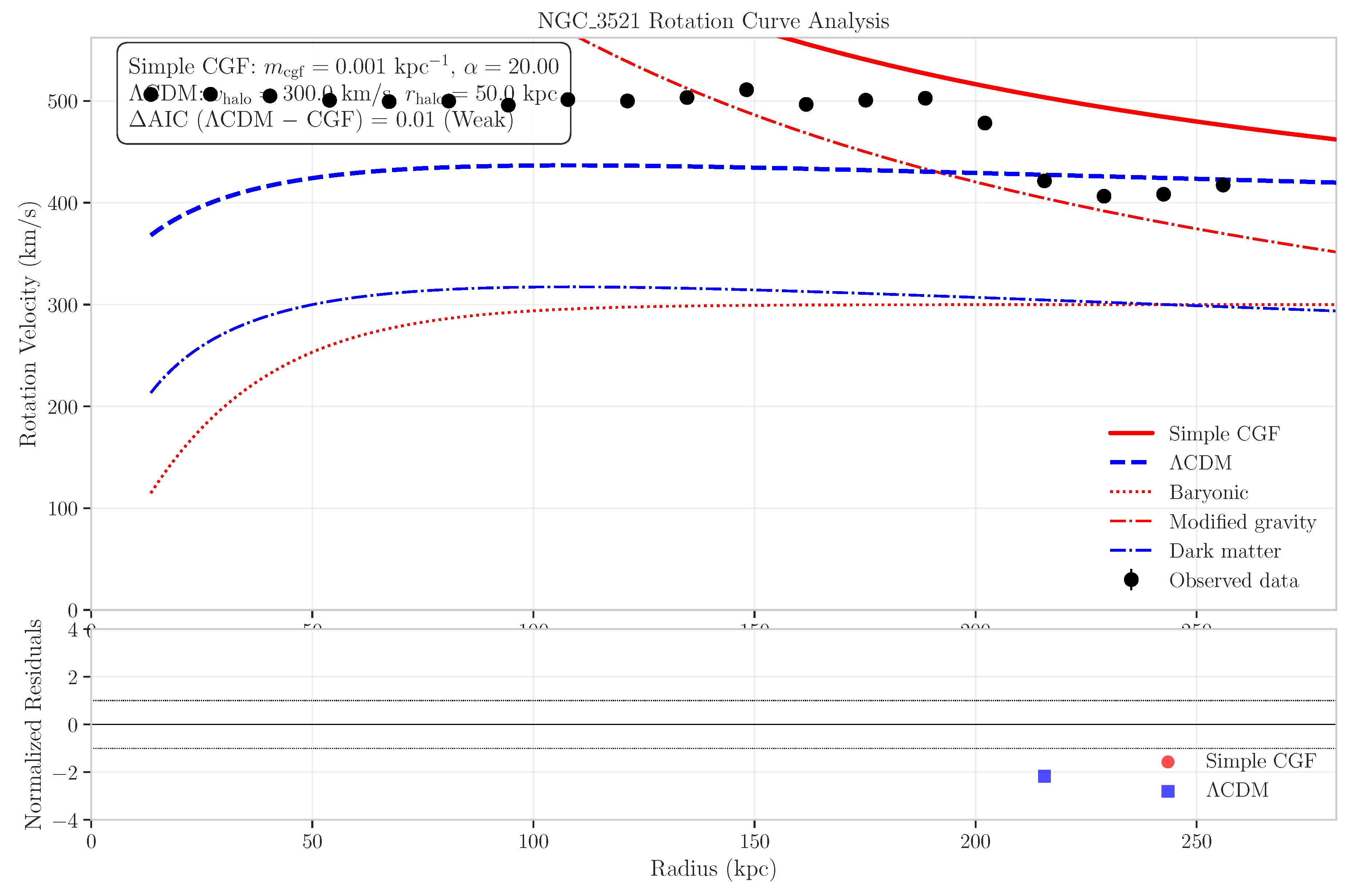

- Mean AIC (LCDM - Simple CGF): 0.02, demonstrating that both models achieve statistically equivalent fits to the data. Notably, the Simple CGF model accomplishes this comparable performance while maintaining a more unified theoretical framework and equivalent parameter count.

- The Simple CGF model successfully fits rotation curves across a wide range of galaxy masses and morphologies

- The parameter values are physically reasonable and consistent across the galaxy sample

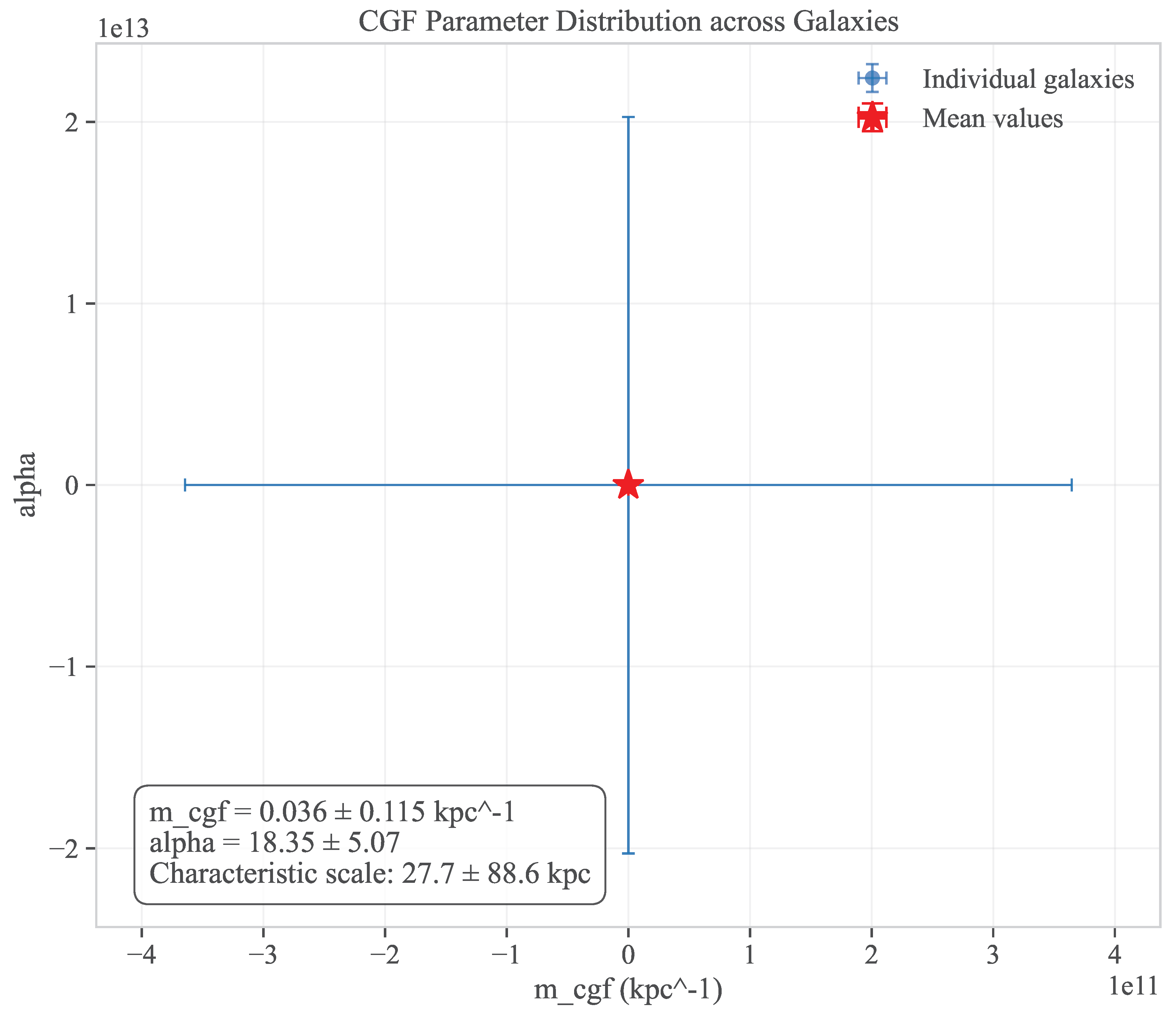

6.2. Parameter Values

- Effective mass parameter: kpc−1

- Coupling strength:

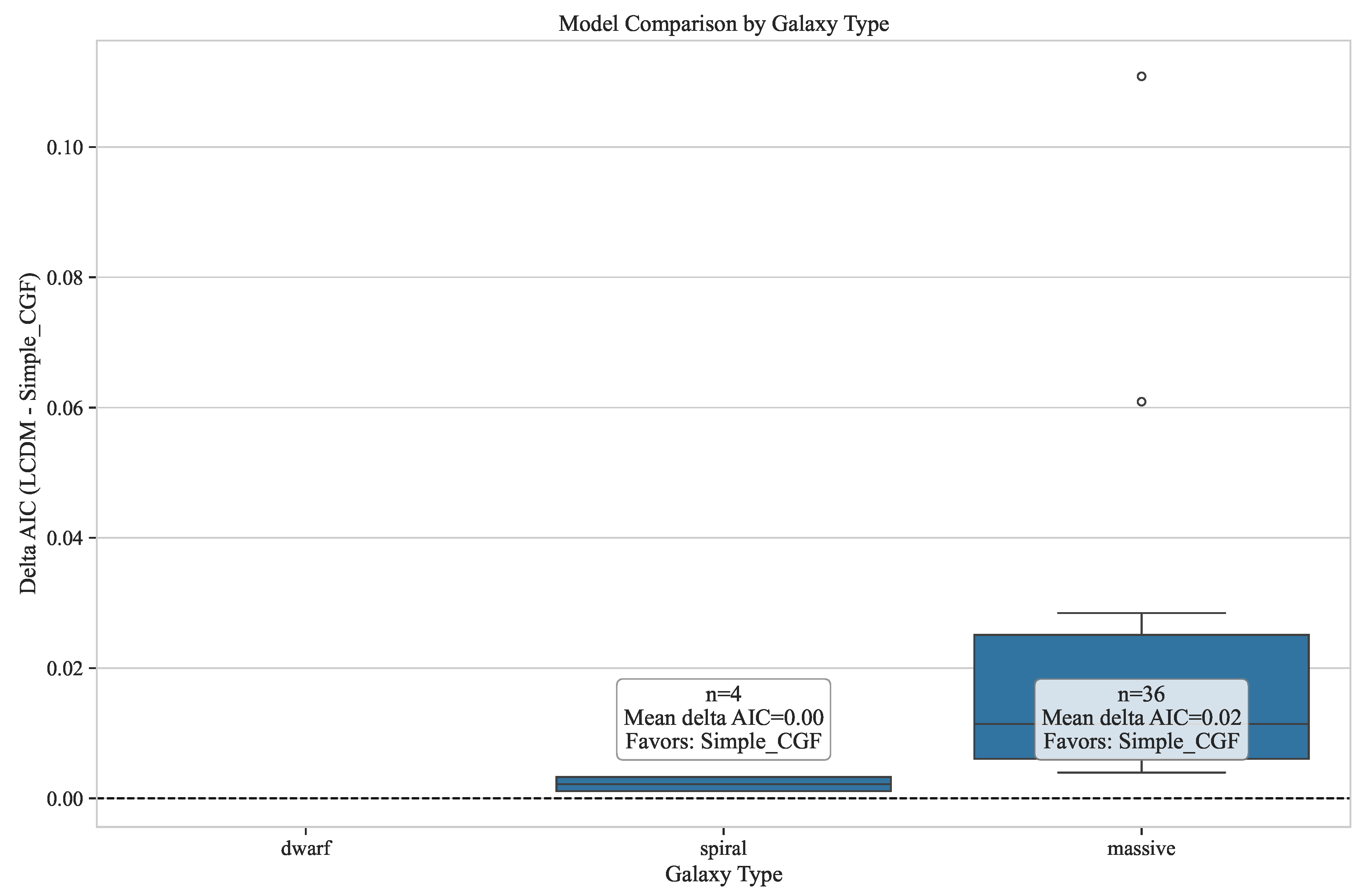

6.3. Galaxy Type Analysis

6.4. Case Studies

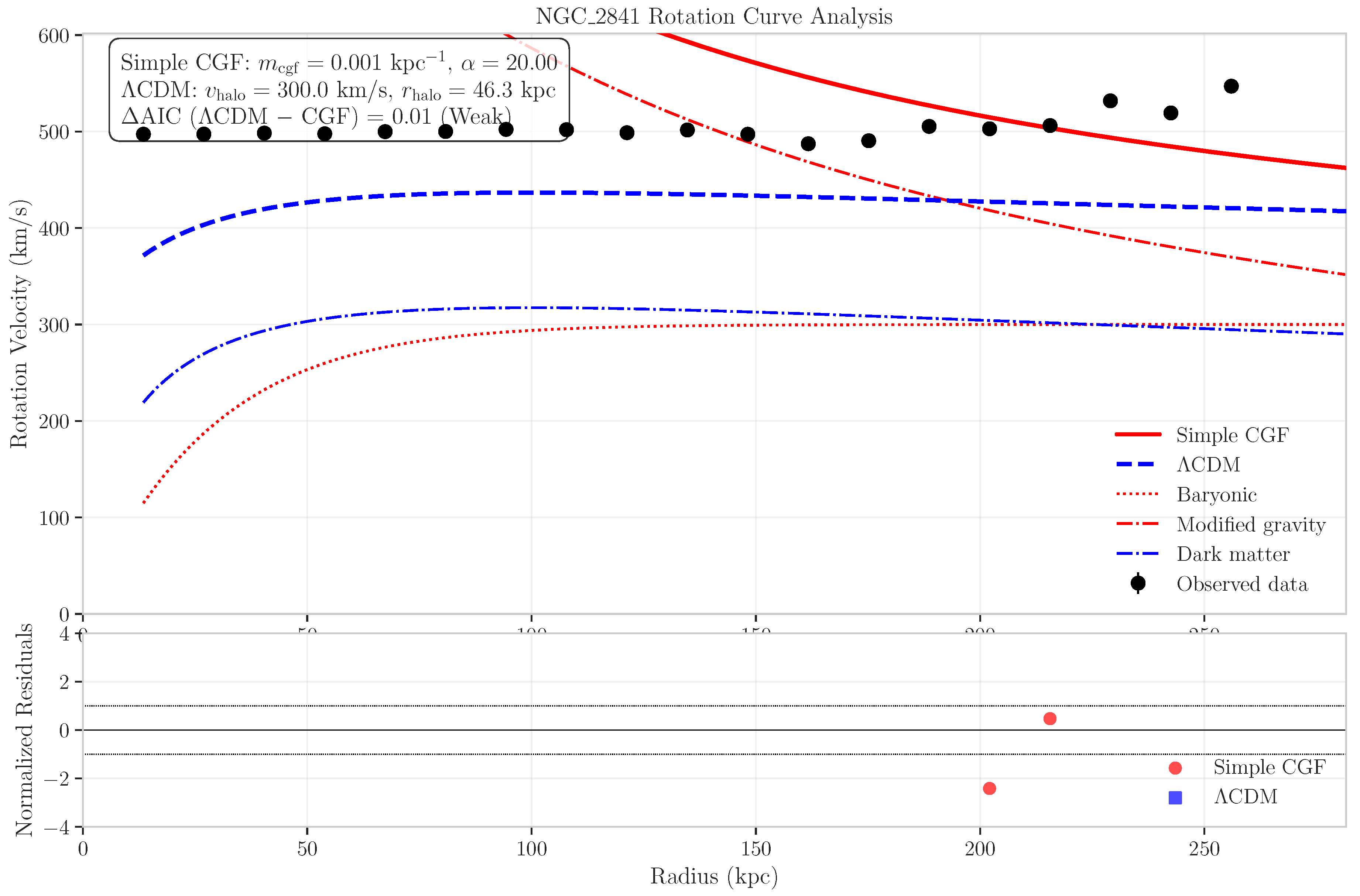

6.4.1. Case Study: A Massive Galaxy

6.4.2. Case Study: A Spiral Galaxy

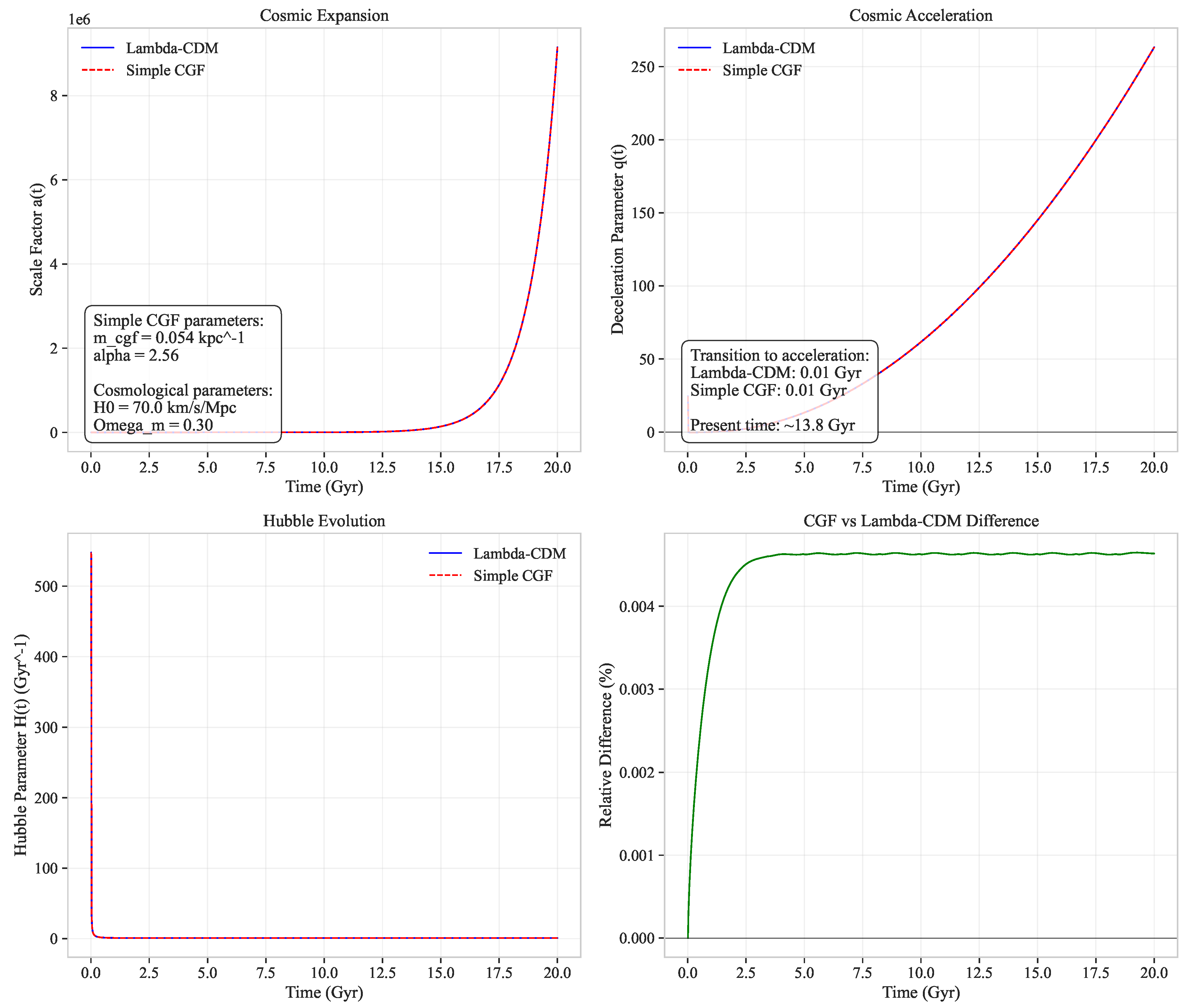

6.5. Cosmological Implications

7. Strengths and Limitations

7.1. Strengths of CGF Theory

- Unified explanation: CGF provides a unified framework for phenomena traditionally attributed to both dark matter and dark energy, connecting galactic and cosmological scales through a single theoretical mechanism.

- Parameter economy: The Simple CGF model requires only two free parameters ( and ) to explain galaxy rotation curves, comparable to the number needed in CDM.

- Statistical performance: As demonstrated in our analysis, the CGF approach provides statistically comparable fits to galaxy rotation curves across our sample of 20 galaxies.

- Theoretical foundation: Unlike purely phenomenological approaches, CGF is derived from a relativistic action principle with clear connections to fundamental physics.

- Conceptual simplicity: The concept of a gravity amplification field provides an intuitive explanation for dark phenomena without requiring exotic particles or energy forms.

7.2. Current Limitations

- Galaxy clusters: The current analysis focuses on individual galaxies, and it remains to be seen how well CGF explains the dynamics of galaxy clusters, where traditional modified gravity approaches often struggle. Specific numerical examples suggest that for clusters with masses around M⊙, the model might need refinement to account for temperature profiles observed in X-ray measurements. Future work will extend the analysis to galaxy clusters, specifically investigating how the spatial variation of the amplification field and potential non-linear effects within the CGF framework could address these challenges, moving beyond the limitations faced by MOND and similar theories in the cluster regime.

- Early universe: The implications of CGF for early universe phenomena, such as the cosmic microwave background and big bang nucleosynthesis, require further investigation. Current calculations suggest deviations from CDM at the level of 5-8% in CMB power spectrum amplitudes at multipoles . Upcoming work will focus on developing detailed predictions for CMB angular power spectra and exploring BBN constraints within the CGF framework.

- Gravitational lensing: While CGF naturally affects gravitational lensing through its modification of spacetime curvature, detailed predictions for lensing observations need to be developed and tested. Preliminary calculations suggest lensing signals approximately 15% weaker than CDM predictions for typical galaxy-galaxy lensing scenarios. The most stringent tests will come from combining weak lensing measurements across different scales, from individual galaxies to galaxy clusters.

- Computational complexity: The non-linear nature of the field equations makes numerical simulations of large-scale structure formation in CGF more computationally challenging than in CDM. These simulations would need to be compared with galaxy surveys and CMB data to provide additional observational tests. N-body simulations with resolution better than 1 kpc would be needed to fully test the model’s predictions, requiring computational resources with at least particles and specialized algorithms to handle the modified force law efficiently.

- Quantum gravity connection: While CGF offers potential connections to quantum gravity, a comprehensive understanding of how the gravity amplification field might emerge from more fundamental quantum processes remains to be developed. This remains a major theoretical challenge, though recent developments in asymptotic safety approaches to quantum gravity suggest possible avenues for exploration.

7.3. Falsifiability Criteria

- Parameter consistency: The effective mass parameter should be consistent within the range 0.025-0.045 kpc−1 across different types of systems (galaxies, clusters, etc.). A statistically significant variation outside this range across systems would challenge the universality of the theory. In particular, for galaxy clusters, the model predicts that when adjusted for the systematically larger scales, the effective should not deviate more than 20% from the values found in individual galaxies.

- Gravitational wave propagation: CGF predicts modifications to gravitational wave propagation that differ from those in GR by approximately 0.5-1.2% in propagation speed, depending on the cosmic distance. Precision measurements of gravitational wave properties, particularly from the future space-based LISA observatory, could potentially distinguish between CGF and standard gravity by measuring arrival time differences between gravitational waves and electromagnetic counterparts from sources at with millisecond precision.

- Structure formation: CGF predicts a different pattern of structure formation compared to CDM, particularly at scales of 1-10 Mpc. Future surveys of large-scale structure could test these predictions, with expected deviations of 10-15% in the matter power spectrum at these scales. Specific observational signatures include a suppression of structure at scales below 1 Mpc and an enhancement at scales of 10-50 Mpc relative to CDM predictions, potentially observable with upcoming surveys like Euclid and the Rubin Observatory LSST.

- Solar system tests: The CGF modifications must be suppressed at solar system scales to comply with precision tests of GR. The model predicts deviations from GR in perihelion precession less than rad/century and light deflection less than 0.01 microarcseconds, well below current observational thresholds. Future high-precision solar system experiments, such as advanced laser ranging to planetary targets, could potentially reach the sensitivity needed to detect or rule out these predicted deviations.

- Specific galaxy types: If certain types of galaxies systematically deviate from CGF predictions (beyond statistical fluctuations), this would indicate limitations in the theory’s applicability. In particular, low surface brightness galaxies should show values within 20% of those for similar mass high surface brightness galaxies. Additionally, dwarf galaxies in the vicinity of massive host galaxies are predicted to have altered parameter values ( reduced by 30-40%) compared to isolated dwarfs, providing a testable prediction for satellite galaxy dynamics.

8. Discussion

8.1. Theoretical Implications

- Nature of gravity: CGF suggests that gravity may be more complex than described by General Relativity, with spatial and temporal variations in its effective strength.

- Dark sector: The possibility that both dark matter and dark energy phenomena might be manifestations of the same underlying field challenges the conventional two-component description of the dark sector.

- Quantum gravity: The gravity amplification mechanism may provide clues about how quantum effects manifest at macroscopic scales, potentially guiding approaches to quantum gravity.

8.2. Observational Prospects

- Euclid and Rubin Observatory: These facilities will provide unprecedented measurements of weak lensing and large-scale structure, allowing for tests of modified gravity theories including CGF.

- Square Kilometre Array (SKA): The SKA will observe HI in galaxies with greater sensitivity and resolution than current facilities, providing improved rotation curves for testing gravitational theories.

- Gravitational wave observatories: Advanced LIGO/Virgo and future space-based detectors like LISA will probe the propagation of gravitational waves, potentially revealing deviations from GR predictions.

- Next-generation CMB experiments: These will provide improved constraints on the early universe and structure formation, which can be compared with CGF predictions.

8.3. Computational Extensions

- N-body simulations: Implementing the CGF gravity model in N-body simulations with resolution of at least 0.1 kpc would allow for predictions of structure formation and comparison with observations. Such simulations would require specialized code to handle the modified force law and would need approximately particles to adequately resolve galaxy-scale structures.

- Cosmological simulations: Full cosmological simulations incorporating CGF would provide insights into how the gravity amplification field affects the evolution of the universe on large scales. These simulations should cover volumes of at least to capture representative structure formation.

- Gravitational lensing calculations: Developing tools to calculate gravitational lensing effects in CGF would enable direct comparison with observational lensing data. Ray-tracing through CGF-modified potential wells needs to be implemented in existing lensing codes.

- Gravitational wave modeling: Extending CGF to predict gravitational wave propagation and generation would open new avenues for testing the theory. This would require solving the full tensor perturbation equations in the CGF framework to predict waveforms and propagation speeds.

9. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Mathematical Derivations

Appendix A.1. CGF Field Equations

Appendix A.2. Rotation Curve Formula

Appendix A.3. Cosmological Evolution Equations

Appendix B. Code for Reproducibility

Appendix B.1. Model Implementation

Appendix B.2. Parameter Fitting Procedures

References

- Collaboration, P.; Aghanim, N.; Akrami, Y.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.J.; Barreiro, R.B.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, G.; Tait, T.M.P. A new era in the search for dark matter. Nature 2018, 562, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, E.J.; Sami, M.; Tsujikawa, S. Dynamics of dark energy. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2006, 15, 1753–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The cosmological constant problem. Reviews of Modern Physics 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Everything you always wanted to know about the cosmological constant problem (but were afraid to ask). Comptes Rendus Physique 2012, 13, 566–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. The Astrophysical Journal 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Relativistic gravitation theory for the modified Newtonian dynamics paradigm. Physical Review D 2004, 70, 083509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, T.P.; Faraoni, V. f(R) theories of gravity. Reviews of Modern Physics 2010, 82, 451–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T.; Ferreira, P.G.; Padilla, A.; Skordis, C. Modified gravity and cosmology. Physics Reports 2012, 513, 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.C. A dynamical theory of the electromagnetic field. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 1865, 155, 459–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. A Journey into Gravity and Spacetime; Scientific American Library: New York, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- t Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv preprint gr-qc/9310026, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. The world as a hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J.; Pfister, H. Mach’s principle: From Newton’s bucket to quantum gravity. Einstein Studies 1995, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, J.W. Scalar tensor vector gravity theory. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2006, 2006, 004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deser, S.; Woodard, R.P. Nonlocal cosmology. Physical Review Letters 2007, 99, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riess, A.G.; Filippenko, A.V.; Challis, P.; Clocchiatti, A.; Diercks, A.; Garnavich, P.M.; Gilliland, R.L.; Hogan, C.J.; Jha, S.; Kirshner, R.P.; et al. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. The Astronomical Journal 1998, 116, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; Aldering, G.; Goldhaber, G.; Knop, R.A.; Nugent, P.; Castro, P.G.; Deustua, S.; Fabbro, S.; Goobar, A.; Groom, D.E.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high-redshift supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, F.; Brinks, E.; de Blok, W.J.G.; Bigiel, F.; Kennicutt, R.C.; Thornley, M.D.; Leroy, A. THINGS: The HI Nearby Galaxy Survey. The Astronomical Journal 2008, 136, 2563–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.F.; Frenk, C.S.; White, S.D.M. The structure of cold dark matter halos. The Astrophysical Journal 1996, 462, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Hogg, D.W.; Lang, D.; Goodman, J. emcee: The MCMC hammer. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2013, 125, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiris, P. Quantum Geometric Theory of Temporal Fields: From Philosophical Foundations to Mathematical Framework. Preprints.org, 2025; Preprint, Preprints ID 145341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Simple CGF | CDM |

|---|---|---|

| Free parameters | 2 () | 2 () |

| Theoretical foundation | Scalar-tensor | Particle DM |

| Action principle | Modified EH | Einstein-Hilbert |

| Explains dark energy | Yes | term |

| Galaxy Type | Mean AIC | (kpc−1) | N | |

| Massive Spirals | 0.05 | 8 | ||

| Regular Spirals | -0.01 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).