1. Introduction

Mandibular defects resulting from tumor destruction create significant functional and aesthetic challenges that profoundly impact patient quality of life [

1]. Osteoblastoma, an uncommon benign bone neoplasm accounting for approximately 1% of all primary bone tumors, exhibits a predilection for the spine and sacrum but can arise in virtually any bone [

2]. Within the craniofacial region, it represents approximately 15% of cases, with the mandible being the most common site of involvement, particularly the posterior region [

3]. The epithelioid variant of osteoblastoma presents unique diagnostic challenges due to its atypical epithelioid osteoblasts within a vascular stroma, which can mimic malignant proliferation [

4]. Large tumors involving extensive portions of the mandible cause severe disfigurement of the lower facial third, with significant mandibular expansion potentially affecting the infratemporal fossa, parapharyngeal space, oral cavity, and floor of the mouth [

5]. This cortical destruction leads to devastating functional consequences, including loss of bony continuity and structural support [

6,

7,

8].

The fibula free flap has emerged as the gold standard for reconstructing composite bone and soft tissue defects in the head and neck region [

9]. Since its initial description by Hidalgo in 1989, this microsurgical technique has become the optimal therapy for complex mandibular reconstructions worldwide [

10]. The fibula's favorable anatomical attributes include a straight, cortical bone segment with sufficient length (average 15.4 cm, up to 25 cm) to address extensive mandibular defects, excellent intrinsic rigidity from its compact bi-cortical structure, and dual blood supply that allows for safe multiple osteotomies [

11,

12]. These characteristics facilitate contouring the flap to mimic mandibular shape and enable future implant placement [

13]. Virtual surgical planning has become indispensable for these complex procedures, creating detailed digital replicas of patient anatomy that facilitate optimal surgical approach selection, treatment plan customization, precise definition of surgical procedures, assessment of desired resection margins, and simulation of surgery to anticipate potential anatomical or technical challenges [

14].

Despite the sophistication of virtual surgical planning, a persistent challenge remains in transferring millimeter-level preoperative accuracy to the operating room environment. The successful execution of fibula free flap reconstruction critically depends on accurate localization, dissection, and anastomosis of vessels at both donor and recipient sites [

15,

16]. Selection and preparation of recipient vessels in the head and neck region constitute a fundamental yet often demanding step, as the facial artery and internal jugular vein may be significantly compromised in patients requiring mandibular reconstruction. When ipsilateral vessels prove unsuitable due to small caliber, fragility, radiation damage, or absence, surgeons must seek alternative recipient sites, potentially necessitating contralateral vessels, more proximal branches of the external or internal carotid system, or interposed venous grafts [

17]. Similarly, intraoperative identification of cutaneous and muscular perforating vessels from the peroneal artery, which are vital for flap irrigation, presents significant technical challenges. The complex three-dimensional anatomy of this region complicates precise anatomical navigation during surgery, and conventional navigation systems often require visual diversion to external monitors, creating focus shift problems that may compromise surgical precision [

18].

Augmented Reality represents a logical evolution beyond traditional navigation systems, offering the potential to superimpose digital information directly onto the surgeon's view of the operative field, providing enhanced anatomical understanding and optimized precision [

19]. Head-mounted displays promise direct integration of virtual anatomy data into the real-world surgical context, allowing more natural interaction without the need for external monitor consultation [

20,

21,

22,

23]. This technology enables a form of enhanced visualization that can facilitate intraoperative decision-making and ultimately improve clinical outcomes [

24]. The objective of this report is to describe the first surgical intervention in Latin America using a holographic surgical navigation system for intraoperative planning and real-time vascular identification during mandibular reconstruction using a fibula free flap, representing a significant advance in translating virtual surgical planning accuracy to the operating room environment.

2. Case Presentation

A 26-year-old previously healthy female presented with a three-month history of progressive left submandibular swelling. Initial symptoms included localized temperature changes and mild masticatory discomfort. The mass demonstrated progressive enlargement with associated pain and significant aesthetic concern prompting medical evaluation. Physical examination by the oral and maxillofacial surgery service revealed a firm, immobile 5×3×5 cm submandibular mass adherent to deep tissue planes with tenderness on palpation. No cervical lymphadenopathy or facial nerve dysfunction was detected. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography demonstrated a 6 × 3 × 5 cm osteolytic lesion of the left mandibular body with characteristics consistent with high tumor vascularity and associated cervical lymph node reaction. Importantly, the lesion demonstrated intimate anatomical relationship with the facial and mandibular arteries without evidence of direct vascular invasion or compromise.

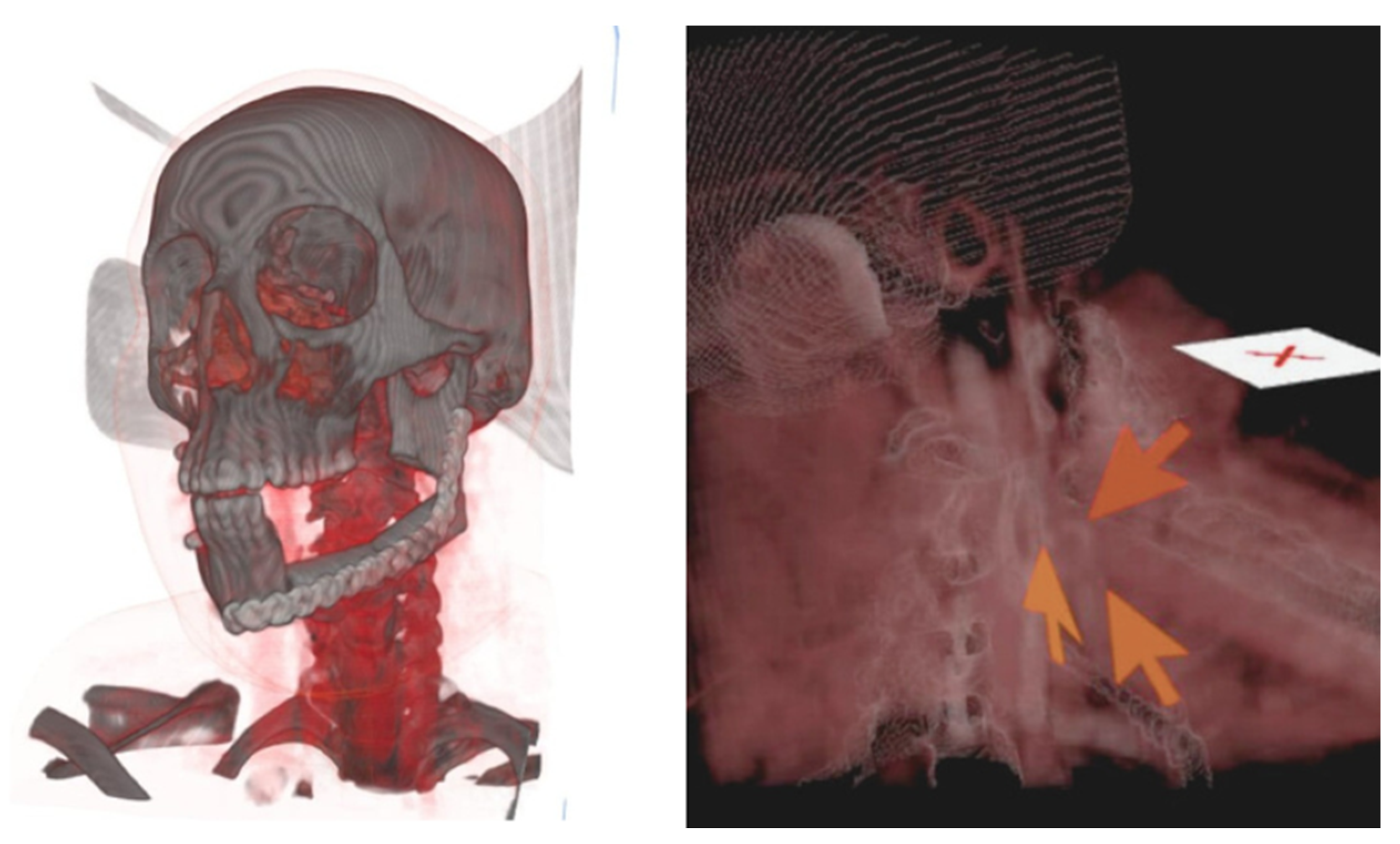

Contrast-enhanced CT angiography of the lower extremities confirmed adequate bilateral vascular patency without atherosclerotic plaques or compromised blood flow. The study documented at least three muscular perforating arteries in each lower extremity with optimal visualization of the peroneal artery pedicle without evidence of anatomical variants or vessel foreshortening. The patient was admitted 24 hours prior to surgery for innovative virtual surgical planning using AR technology. Meta Quest 3 headsets were utilized in conjunction with Medical Holodeck software to generate three-dimensional holographic models. The planning protocol involved extraction of DICOM data from previously acquired CT studies with subsequent processing through specialized software platforms. Independent holograms of the craniofacial region and lower extremities were generated, enabling detailed anatomical visualization of critical structures. The craniofacial hologram precisely identified the facial artery origin in the distal two-thirds of the left mandibular ramus, demonstrating lateral deviation secondary to mass effect from the tumor. Virtual markers were established to delineate the exact vascular origin site and guide optimal surgical incision placement (

Figure 1). For donor site planning, the lower extremity hologram enabled precise identification of bilateral perforating arteries, prioritizing the extremity contralateral to the lesion side. Holographic model superimposition over the patient's anatomy facilitated cutaneous marking of the peroneal artery pedicle and muscular perforators using sterile surgical markers.

2.1. Surgical Technique

The patient was positioned supine under general anesthesia with nasotracheal intubation. Two simultaneous surgical teams were established: the tumor resection and mandibular reconstruction team, and the free fibular flap harvest team. During the resection phase, the primary surgeon utilized AR headsets to superimpose the hologram over the patient's anatomy. This technology enabled precise tumor resection margin marking and real-time identification of critical vascular landmarks during dissection. A 6 cm left submandibular incision was performed followed by layer-by-layer dissection using monopolar and bipolar electrocautery. Throughout the dissection, the AR system provided continuous notifications regarding facial artery trajectory. Upon reaching the deep plane, the facial artery and accompanying veins were identified and isolated, preserving these structures during osteotomy and tumor resection. The resulting mandibular defect was measured using the millimetric ruler incorporated within the AR software, documenting an approximately 12 cm length defect. The primary surgeon, utilizing AR headsets, transitioned to the flap harvest team to delineate exact dimensions of the required bone segment. Communication to the team specified the need for a 12 cm fibular segment with three preplanned osteotomies marked both in the application and on the flap. A 12 cm osteo-fascial flap was successfully harvested without skin component, preserving the arterial and venous pedicle. Subsequently, graft modeling was performed to recreate mandibular ramus and angle anatomy, achieving an L-shaped configuration. Bone graft fixation was accomplished using titanium plating on the external cortex. Flap revascularization was achieved through end-to-end microvascular anastomosis using interrupted 8-0 nylon suture technique for both arterial and venous facial vessels. Closure was performed in anatomical layers: oral mucosa with 4-0 catgut, subcutaneous tissue with absorbable suture, and skin with continuous 3-0 polypropylene intradermal suture. At the lower extremity donor site, primary wound closure was performed with split-thickness skin graft placement for distal defect closure measuring approximately 5 cm.

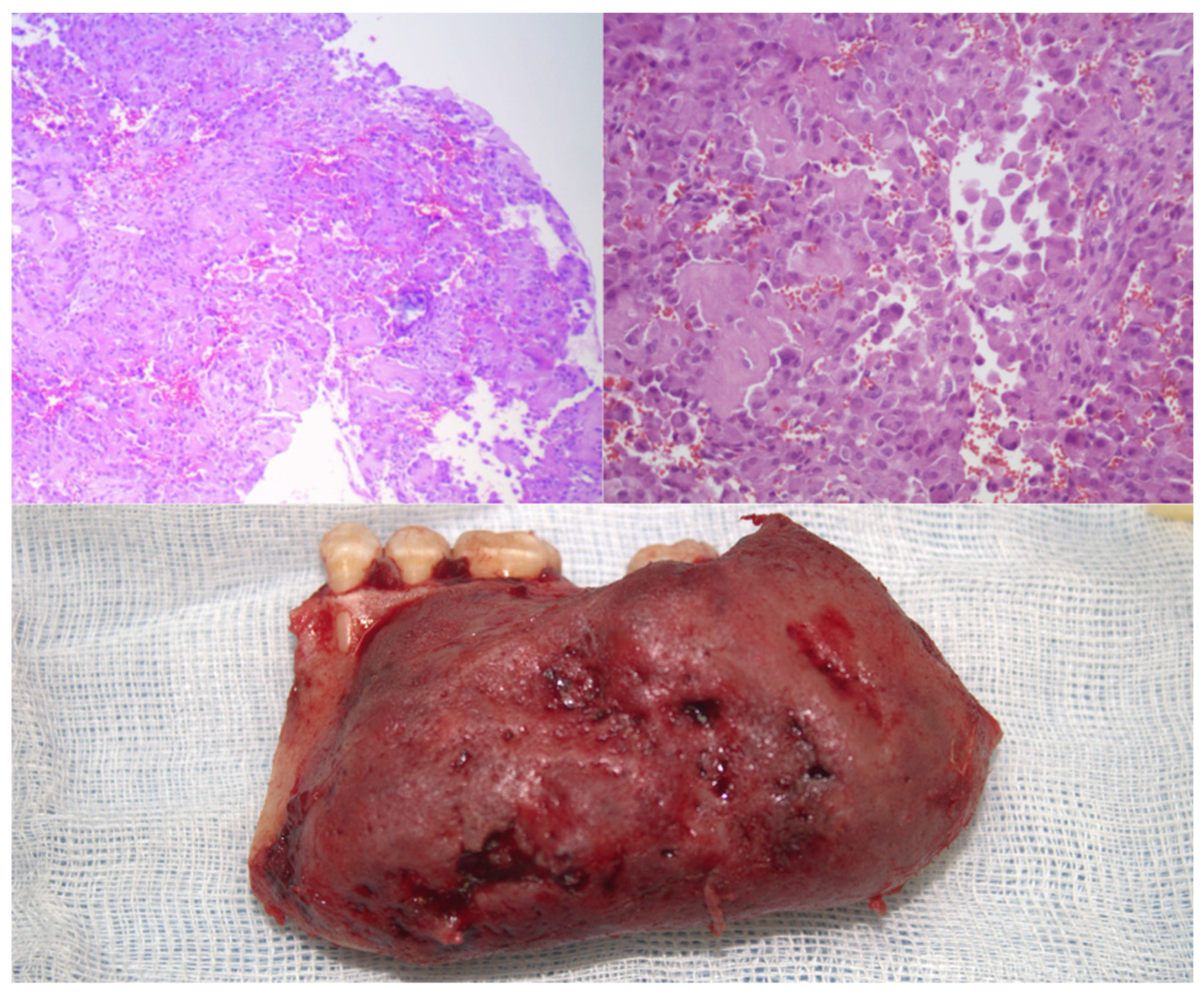

The histological examination revealed the presence of a cellular infiltrate whose initial morphological characteristics suggested a possible histiocytic process (

Figure 2). However, the complexity of the observed cellular pattern required complementary studies using immunohistochemical techniques to establish an appropriate differential diagnosis and to determine the precise nature of the lesion. The immunohistochemical studies provided definitive diagnostic information through the evaluation of multiple specific markers. The assessment of CD68 was entirely negative, thereby conclusively ruling out any histiocytic-type differentiation. Similarly, the S-100 protein showed absolute negativity, thus excluding a neural or melanocytic origin for the lesion. Conversely, the analysis of SATB2 demonstrated intense and diffuse expression with a maximum score, unequivocally confirming the osteoblastic differentiation of the tumor cells.

2.2. Postoperative Course

A nasogastric tube was placed immediately postoperatively for enteral access maintenance. During the first 24 hours, the patient experienced fever of 37.8°C which resolved with antipyretic therapy without additional clinical manifestations. In the postoperative day 3 a head and neck CT was made to assess the viability of the microvascular flap and microvascular anastomosis (

Figure 3).

Oral feeding was initiated with liquids at 48 hours postoperatively, progressing satisfactorily to juices, teas, and water, permitting nasogastric tube removal. On postoperative day three, pureed foods were introduced and assisted ambulation was initiated by the physical medicine and rehabilitation service. By postoperative day five, the patient advanced to soft diet consistency without evidence of food intolerance, masticatory pain, or dysphagia. Hospital discharge occurred on postoperative day seven without complications. At three months postoperatively, the patient returned for ambulatory follow-up demonstrating near-complete donor site wound healing in the left leg and complete submandibular wound healing (

Figure 4). No purulent drainage, wound dehiscence, or infection signs were evident. The patient continued physical rehabilitation to resume complete preoperative physical activity, reporting return to occupational and personal activities independently without additional assistance requirements.

3. Discussion

This case represents the first successful application of low-cost holographic surgical navigation technology for complex microsurgical mandibular reconstruction in Latin America, demonstrating the feasibility of translating advanced augmented reality capabilities into routine clinical practice. The Meta Quest 3 headset combined with Medical Holodeck software provided real-time anatomical guidance that enhanced surgical precision during both tumor resection and fibula free flap harvest, establishing a novel paradigm for intraoperative navigation in reconstructive microsurgery. The three-dimensional holographic visualization provided unprecedented anatomical detail, enabling precise identification of critical vascular structures and optimal surgical approach planning [

25].

Real-time intraoperative guidance through AR technology facilitated accurate tumor resection margins and preserved vital anatomical structures, particularly the facial artery which showed lateral deviation due to tumor mass effect. The observed advantages of holographic navigation extend beyond traditional surgical planning methodologies. The technology enabled precise real-time identification of critical vascular structures, particularly the facial artery trajectory altered by tumor mass effect, which would have required extensive dissection using conventional techniques. Unlike handheld Doppler ultrasonography, which provides auditory feedback requiring interpretation and offers limited spatial resolution, the holographic system delivered direct visual overlay of vascular anatomy onto the operative field [

22]. This enhanced anatomical precision potentially reduced vascular dissection time and increased surgeon confidence during critical phases of the procedure [

26]. Furthermore, the technology served as an invaluable educational tool for surgical residents, providing three-dimensional anatomical visualization that enhanced understanding of complex microvascular relationships without compromising sterile technique or requiring additional personnel for navigation system operation.

Several important limitations must be acknowledged regarding this initial clinical application. As a single case report, these findings cannot be generalized to broader patient populations or diverse anatomical presentations. The learning curve associated with holographic navigation technology presents challenges for both primary surgeons and surgical team members, requiring dedicated training time and technical proficiency development. Registration accuracy, defined as the precise alignment between holographic projections and actual patient anatomy, remains a significant technical challenge that may be influenced by patient positioning changes, tissue deformation during surgery, or calibration errors [

19]. Additionally, prolonged use of head-mounted displays during extended microsurgical procedures may cause ergonomic discomfort or visual fatigue that could potentially impact surgical performance, though this was not observed in the current case. The integration of augmented reality technology in surgical practice represents an evolving field with expanding applications across multiple specialties [

27]. While limited reports exist regarding holographic navigation in head and neck reconstruction, similar technologies have demonstrated promise in neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery, and cardiac procedures. The accessibility and affordability of consumer-grade augmented reality devices, such as the Meta Quest 3, democratize advanced surgical navigation capabilities that were previously limited to specialized centers with expensive dedicated systems. Future applications of this technology may include complex pelvic reconstruction, breast reconstruction with perforator flaps, and other microsurgical procedures requiring precise anatomical navigation. Validation of this technique through multicenter studies with larger patient cohorts will be essential to establish standardized protocols, determine optimal indications, and quantify improvements in surgical outcomes, operative time, and complication rates.

4. Conclusions

Holographic intraoperative navigation using commercially available devices represents an exciting and accessible evolution of surgical planning technology, with significant potential to enhance outcomes in reconstructive microsurgery by bridging the critical gap between preoperative virtual planning and intraoperative execution. Future applications of AR technology in microsurgery may include enhanced training platforms, improved preoperative patient counseling, and standardization of complex reconstructive techniques. However, further studies are required to establish comprehensive protocols and validate long-term outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.R.M. and Y.I.V.; methodology, H.G.A.; software, N.A.R.M.; validation, H.G.A., J.H.B.R. and F.H.A.; formal analysis, M.Q.P., C.C.A. and R.M.H.; investigation, N.A.R.M.; resources, C.R.M.; data curation, C.R.E..; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.R.M.; writing—review and editing, N.A.R.M.; visualization, A.I.R.C.; supervision, J.H.B.R.; project administration, N.A.R.M.; funding acquisition, H.G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient for her cooperation and consent to share her case, which has been invaluable in preparing this report and contributing to our understanding and management of this condition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Suster, D.; Mackinnon, A.C.; Jarzembowski, J.A.; Carrera, G.; Suster, S.; Klein, M.J. Epithelioid osteoblastoma. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 17 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2022, 125, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, D.P.; Fernandes, R.P.; Silva, M.M.; Bunnell, A. A benign tumor of substantial size: Mandibular epithelioid osteoblastoma in a socioeconomically challenged patient. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2025, 53, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfin, A.; Boriani, S.; Gambarotti, M.; Bandiera, S.; Gasbarrini, A. Can osteoblastoma evolve to malignancy? A challenge in the decision-making process of a benign spine tumor. World Neurosurg. 2020, 136, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ibraheem, A.; Yacoub, B.; Barakat, A.; Dergham, M.Y.; Maroun, G.; Haddad, H.; Haidar, M.B. Case report of epithelioid osteoblastoma of the mandible: findings on positron emission tomography/computed tomography and review of the literature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, e16–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.S.F.; de Andrade, B.A.B.; Romañach, M.J.; Pereira, N.B.; Gomes, C.C.; Mariz, B.A.L.A.; Fonseca, F.P. Clinicopathologic study of 6 cases of epithelioid osteoblastoma of the jaws with immunoexpression analysis of FOS and FOSB. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, M.; Hoshimoto, Y.; Seta, S.; Nakanishi, Y.; Sasaki, M.; Aoki, T.; Ota, Y. A case of extremely rare mandibular osteoblastoma successfully treated with functional reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2024, 36, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harazono, Y.; Yoshitake, H.; Fukawa, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Yoda, T. Osteoblastoma in the mandible of an older adult patient without FOS gene rearrangement: A case report and literature review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Med. Pathol. 2024, 36, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, J.D.; Murphey, M.D.; Castle, J.T. Epithelioid Osteoblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2012, 6, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliss, E.; Yanko, R.; Bracha, G.; Teman, R.; Amir, A.; Horowitz, G.; Muhanna, N.; Fliss, D.M.; Gur, E.; Zaretski, A. The Evolution of the Free Fibula Flap for Head and Neck Reconstruction: 21 Years of Experience with 128 Flaps. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, R.; Sacco, N.; Hamid, U.; Ali, S.H.; Singh, M.; Blythe, J.S.J. Microsurgical Reconstruction of the Jaws Using Vascularised Free Flap Technique in Patients with Medication-Related Osteonecrosis: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9858921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, J.M.; Chung, C.H.; Chang, Y.J. Head and neck reconstruction using free flaps: a 30-year medical record review. Arch. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 22, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.L.; Haveles, C.S.; Rezzadeh, K.S.; Nolan, I.T.; Castro, R.; Lee, J.C.; Steinbacher, D.; Pfaff, M.J. Virtual Surgical Planning for Mandibular Reconstruction With the Fibula Free Flap: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knitschke, M.; Sonnabend, S.; Bäcker, C.; Schmermund, D.; Böttger, S.; Howaldt, H.-P.; Attia, S. Partial and Total Flap Failure after Fibula Free Flap in Head and Neck Reconstructive Surgery: Retrospective Analysis of 180 Flaps over 19 Years. Cancers 2021, 13, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M.L.; Rosen, E.B.; Allen, R.J.; Nelson, J.A.; Matros, E.; Gelblum, D.Y. Immediate dental implants in fibula free flaps to reconstruct the mandible: A pilot study of the short-term effects on radiotherapy for patients with head and neck cancer. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2020, 22, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.T.; Coppit, G.L.; Burkey, B.B.; Netterville, J.L. Use of the ulnar forearm flap in head and neck reconstruction. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002, 128, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.-Y.; Liu, W.-C.; Chen, L.-W.; Chen, C.-F.; Yang, K.-C.; Chen, H.-C. Osteomyocutaneous Free Fibula Flap Prevents Osteoradionecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Head and Neck Cancer Reconstruction. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gemert, J.T.M.; Abbink, J.H.; van Es, R.J.J.; Rosenberg, A.J.W.P.; Koole, R.; Van Cann, E.M. Early and late complications in the reconstructed mandible with free fibula flaps. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Chung, C.H.; Chang, Y.J. Free-flap reconstruction in recurrent head and neck cancer: A retrospective review of 124 cases. Arch. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 21, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gsaxner, C.; Pepe, A.; Li, J.; Ibrahimpasic, U.; Wallner, J.; Schmalstieg, D.; Egger, J. Augmented Reality for Head and Neck Carcinoma Imaging: Description and Feasibility of an Instant Calibration, Markerless Approach. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 200, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.C.; Schilling, C.; McGurk, M. Augmented reality visualization in head and neck surgery: an overview of recent findings in sentinel node biopsy and future perspectives. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 54, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tel, A.; Raccampo, L.; Vinayahalingam, S.; Troise, S.; Abbate, V.; Dell'Aversana Orabona, G.; Sembronio, S.; Robiony, M. Complex Craniofacial Cases through Augmented Reality Guidance in Surgical Oncology: A Technical Report. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercenelli, L.; Babini, F.; Badiali, G.; Battaglia, S.; Tarsitano, A.; Marchetti, C.; Marcelli, E. Augmented Reality to Assist Skin Paddle Harvesting in Osteomyocutaneous Fibular Flap Reconstructive Surgery: A Pilot Evaluation on a 3D-Printed Leg Phantom. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 804748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.; Xu, J.; Pfister, M.; Atoum, J.; Prasad, K.; Miller, A.; Topf, M.; Wu, J.Y. Development of an augmented reality guidance system for head and neck cancer resection. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabber, A.; Ayoub, N.; Redick, T.; Gesenhues, J.; Kniha, K.; Möhlhenrich, S.C.; Raith, S.; Abel, D.; Hölzle, F.; Winnand, P. Comparison of augmented reality and cutting guide technology in assisted harvesting of iliac crest grafts - A cadaver study. Ann. Anat. 2022, 239, 151834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tel, A.; Zeppieri, M.; Robiony, M.; Sembronio, S.; Vinayahalingam, S.; Pontoriero, A.; Pergolizzi, S.; Angileri, F.F.; Spadea, L.; Ius, T. Exploring Deep Cervical Compartments in Head and Neck Surgical Oncology through Augmented Reality Vision: A Proof of Concept. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochandiano, S.; García-Mato, D.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Moreta-Martinez, R.; Tousidonis, M.; Navarro-Cuellar, C.; Navarro-Cuellar, I.; Salmerón, J.I.; Pascau, J. Computer-Assisted Dental Implant Placement Following Free Flap Reconstruction: Virtual Planning, CAD/CAM Templates, Dynamic Navigation and Augmented Reality. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 754943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Miller, A.; Sharif, K.; Colazo, J.M.; Ye, W.; Necker, F.; Baik, F.; Lewis Jr, J.S.; Rosenthal, E.; Topf, M.C. Augmented-Reality Surgery to Guide Head and Neck Cancer Re-resection: A Feasibility and Accuracy Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 4994–5000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).