1. Introduction

Mandibular reconstruction in oral and maxillofacial surgery remains one of the most challenging procedures due to the anatomical complexity and functional significance of the mandible.[

1] Mandibular defects can arise from various causes, including benign and malignant tumor resection, severe trauma, congenital deformities, infections,[

2] and failed previous reconstruction attempts. The mandible plays a crucial role in forming the lower facial structure and is essential for fundamental functions such as mastication, speech, breathing, and swallowing. Therefore, mandibular reconstruction must consider the restoration of these functions while ensuring sufficient resistance to repetitive physical forces generated during various functional activities. Furthermore, since the mandible significantly influences facial aesthetics, the aesthetic outcome must also be carefully considered. Due to this functional and aesthetic importance, mandibular reconstruction surgery is essential for restoring patients' quality of life.

The optimal approach to restoring both functional and aesthetic elements of the mandible is to reconstruct it as close as possible to its original or normal anatomical structure. Traditionally, this has been accomplished using autogenous bone and flap transplantation along with mandibular reconstruction plates. However, a major limitation of these conventional reconstruction methods is the inherent difficulty in achieving perfect mandibular alignment and contour when relying solely on intraoperative assessment. This challenge particularly arises from the mandible's complex anatomical structure, which includes two temporomandibular joints capable of rotational and sliding movements connecting it to the maxilla, allowing free movement, along with its three-dimensional curved form following the dental arch, and its intricate interactions with various masticatory and deglutition muscles.[

3]

These methods heavily depend on the expertise of the oral and maxillofacial surgeon and intraoperative decision-making. Surgical outcomes can vary significantly based on the surgeon's skill level, and discrepancies between preoperative plans and actual surgical results are common. Such discrepancies can lead to various complications, including malocclusion, facial asymmetry, plate fatigue fracture, screw loosening, and non-union of transplanted autogenous bone. Additional surgeries may be required to address these issues, prolonging the recovery period and impacting the patient's quality of life.

Recent advances in medical technology, particularly computer-aided patient-specific surgical simulation and 3D printing technology, have transformed the approach to mandibular reconstruction surgery.[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] Computer-aided surgical simulation enables not only precise lesion resection but also planning for ideal anatomical structure restoration. Based on this, patient-specific surgical guides and fixation plates can be manufactured using 3D printing technology, offering the potential to significantly enhance surgical precision. The use of these patient-specific devices allows surgeons to plan and execute reconstruction more accurately, reducing the uncertainties inherent in conventional approaches and achieving more predictable results.[

10]

This surgical approach has shown particularly promising results in mandibular reconstruction using fibular free flaps[

11,

12,

13]. Recent studies have demonstrated reduced operation times and predictable outcomes through accurate bone harvesting using cutting guides and precise positioning with customized plates[

14,

15,

16]. The Deep Circumflex Iliac Artery (DCIA) flap with internal oblique muscle, which can provide sufficient bone comparable to the original mandibular contour and restore natural mandibular morphology with minimal or no osteotomy, is also frequently used as a donor site for mandibular reconstruction[

17]. However, research on reconstruction using DCIA flaps with surgical guides and customized plates remains limited due to the complexity of donor site bone morphology, limited pedicle length, and restrictions in musculoskeletal free flap form during harvest, which require various surgical considerations during surgical planning.[

18,

19]

This study aims to evaluate the preoperative and postoperative accuracy and utility of mandibular reconstruction using DCIA musculoskeletal free flaps with the aid of patient-specific surgical guides and customized plates in five patients requiring mandibular reconstruction.

2. Materials and Methods

(1) Study design

This clinical trial was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Chosun University Dental Hospital. From March 2024, patients who visited Chosun University Dental Hospital and were in need of mandibular reconstruction and wished to apply for this clinical trial were enrolled. All clinical trial procedures were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board, and all patients signed informed consent forms.

(2) Virtual Surgical Planning

All patients underwent preoperative CBCT and pelvic CT scans. DICOM files were acquired with a slice thickness of 0.3 mm for CBCT and 0.5 mm for pelvic CT. The obtained DICOM files were processed using Mimics software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) to segment the mandible, iliac bone, and lesion areas. For patients undergoing revision surgery due to failed previous reconstruction, additional mandibular models from before the initial surgery were obtained. Preoperative simulation was performed using 3-matic software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium), and mandibular osteotomy lines were designed considering the characteristics of each lesion, remaining teeth, and anatomical structures. The position and size of the iliac crestal bone for reconstruction of mandibular defects were planned, and reconstruction plates were designed for ideal positioning. When additional osteotomy or trimming was required for the iliac donor site where the reconstruction plate would be positioned, osteotomy or trimming planes were planned.

(3) Customized plates design and fabrication

Surgical guides and Patient-specific plates were designed based on the virtual surgical plan by Anymedi Solution (Anymedi Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea). The plates were customized with varying thicknesses ranging from 2mm to 3mm to match the anatomical contours while maintaining adequate strength. Each plate was designed with 2.4mm diameter holes to accommodate 2.3mm reconstruction screws, ensuring secure fixation of both the native mandible and the DCIA flap. The plates were manufactured using medical-grade titanium alloy (Ti6Al4V) through selective laser melting (SLM) technology. (Cusmedi©, Sungnam, Korea). The design focused on achieving optimal adaptation to both the native mandible and the planned DCIA flap position while maintaining a low profile to minimize soft tissue irritation. The final plates were sterilized using standard autoclave protocols before surgical use.

(4) Surgical technique

All surgeries were performed by the same experienced surgeon specializing in tumor resection and reconstruction. Based on the size and location of the lesion, either an intraoral approach or submandibular approach was utilized. Lesion resection was performed using the mandible resection guide. The internal oblique muscle and DCIA were harvested, and iliac crestal bone was harvested using the iliac resection guide. The bone flap was appropriately shaped using osteotomy and trimming guides, followed by microvascular anastomosis with the facial artery and vein. The mandibular reconstruction site was fixed using customized plates, and donor site defects were augmented using titanium mesh and allogenic bone chips (ReadiGRAFT Cancellous Chips, LifeNet Health, Virginia Beach, Virginia, USA).

(5) Data analysis

All patients harvested postoperative CT scans, and the reconstructed mandible was segmented using Mimics software following the same method as the preoperative analysis. Using 3-matic software, the preoperative planned model and postoperative model were superimposed, and average and maximum errors were analyzed.

3. Results

(1) Representative case

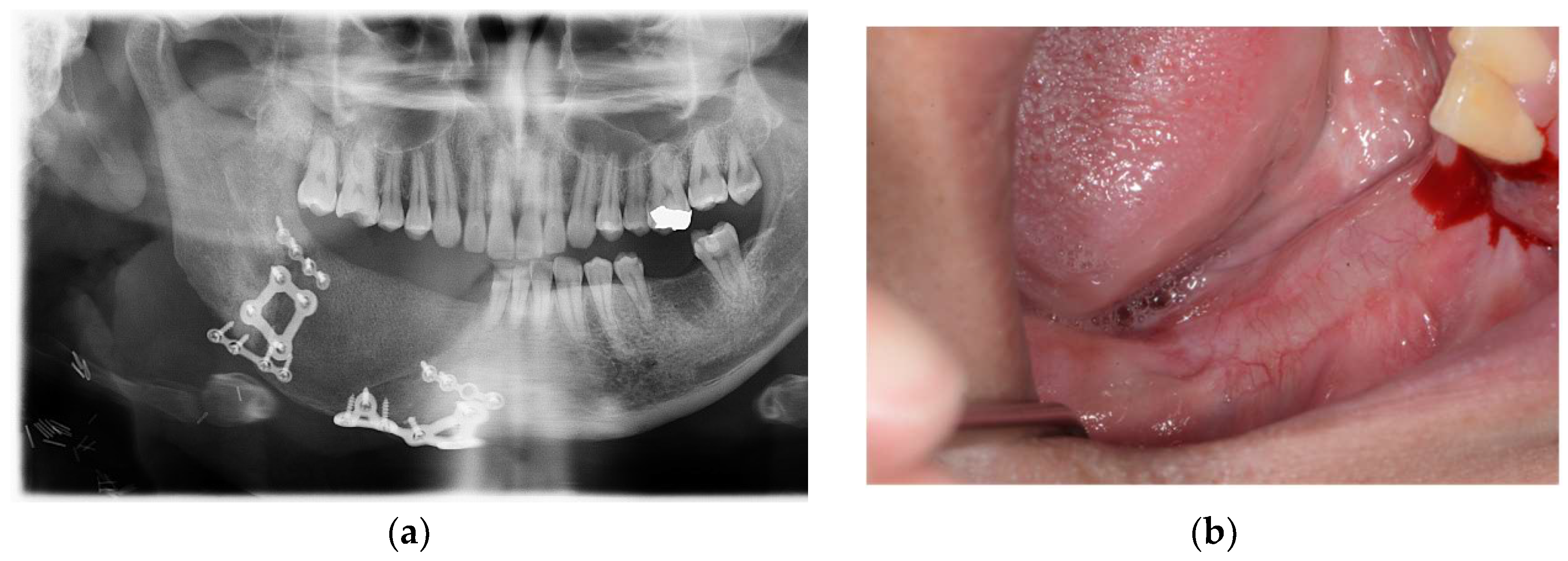

A 31-year-old male patient who underwent segmental mandibulectomy and DCIA iliac crestal free flap reconstruction for mandibular defect presented with plate exposure and non-union in the reconstruction site due to the infection of reconstruction site. (

Figure 1)

Based on the preoperative mandibular CT from the initial lesion, the ideal mandibular form was determined. (

Figure 2)

Reconstruction with bicortical DCIA flap was planned for the corresponding the mandibular position. (

Figure 3)

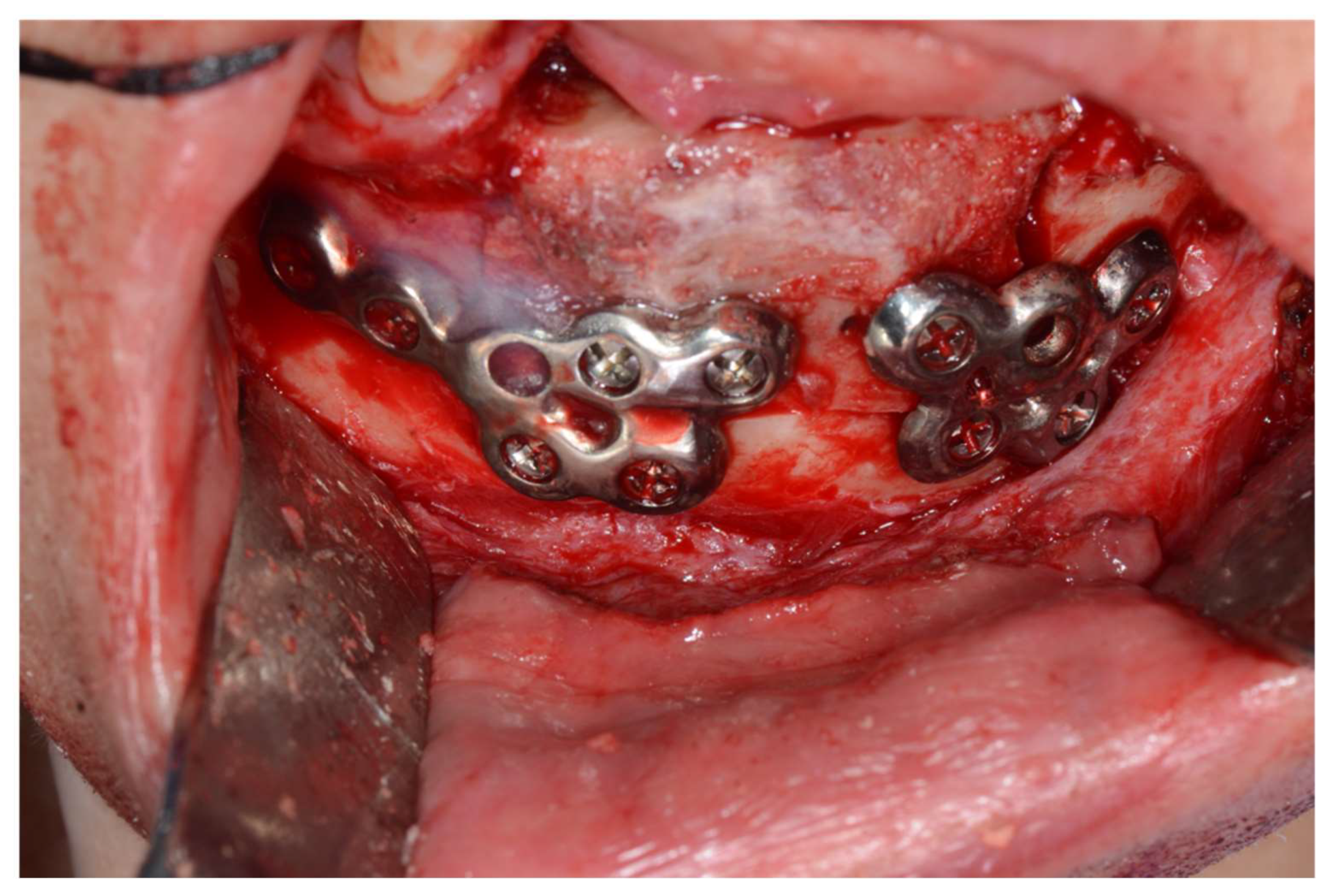

Surgical guides and customized plates were manufactured according to the preoperative plan and reconstruction was performed using these surgical guide and customized plates. (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5)

Accuracy analysis was performed using postoperative CT scans. (

Figure 6). Reconstruction of the mandible was successful, and no unusual findings were observed during the 6-month follow-up.(

Figure 7)

(2) Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 5 patients were included in this study. The mean age of the patients was 49.6 ± 20.5 years (range: 25-73 years), with a gender distribution of 3 males and 2 females. The most common diagnosis was ameloblastoma (3 cases), followed by odontogenic keratocyst (1 case) and ossifying fibroma (1 case) (

Table 1).

The surgical procedures performed included segmental mandibulectomy (2 cases), surgical enucleation & peripheral ostectomy (2 cases), and marginal mandibulectomy (1 case). For reconstruction, bicortical DCIA flap was used in 3 cases and monocortical DCIA flap in 2 cases. The mean span length of the defects was 53.4 ± 20.5 mm (range: 29-84 mm). Postoperative complications occurred in one case (20%), which presented with screw loosening, while the remaining four cases showed no complications. All DCIA flaps achieved successful reconstruction with 100% survival rate, and no cases of flap failure or vascular complications were observed.

The mean operation time was 506.8 ± 112.8 minutes, with estimated blood loss averaging 430.0 ± 218.2 mL. The average hospital stay was 23.2 ± 7.8 days. Notably, cases 4 and 5 showed shorter operation times, which might be attributed to the increased surgical experience with this technique.

(3) Accuracy Results of Virtual Surgical Planning Compared to Actual Surgical Outcomes

The accuracy of mandibular reconstruction was evaluated by comparing the preoperative virtual surgical plan with postoperative CT data using color-coded discrepancy mapping. The mean surface deviation between the virtual plan and the actual surgical outcome was 0.73 ± 0.23 mm across all cases, with individual values ranging from 0.32 mm to 0.97 mm (

Table 2). The maximum deviation observed ranged from 3.87 mm to 7.83 mm, with a mean maximum error of 5.41 ± 1.35 mm.

The lowest average error was observed in Case 5 (0.32 mm), while Case 1 showed the highest average error (0.97 mm). Regarding maximum deviations, Case 1 exhibited the highest value at 7.83 mm, though its average error remained relatively low at 0.97 mm. The standard deviation of surface measurements ranged from 0.52 to 1.33, indicating consistent precision across different regions of the reconstructed mandible.

(4) Complications and Management

One patient (Case 3) developed screw loosening at 3 months postoperatively. The patient presented with mobility of the plate with infection. CT imaging revealed loosening of the posterior screws. The plate was removed under local anesthesia, and the underlying DCIA flap showed satisfactory bone union. This complication led to modification of the plate design from four holes to six or more holes in subsequent cases.

4. Discussion

While mandibular reconstruction using DCIA flaps offers advantages such as sufficient bone height and natural mandibular contour reproduction, meticulous surgical planning is required due to the complex donor site bone morphology and limited pedicle length. In particular, Case 1, our representative case, required the use of the contralateral iliac crestal bone due to a previous failed DCIA flap reconstruction. This resulted in the internal oblique muscle attachment site being positioned on the buccal aspect where the reconstruction plate needed to be fixed. Consequently, iliac bone trimming had to accommodate the muscle tissue, making it impossible to pre-plan the trimming area. This factor likely contributed to Case 1 showing the highest average and maximum errors, though the accuracy achieved can be considered satisfactory given these circumstances. During the study, one case developed screw loosening during the three-month follow-up period, necessitating removal of the one plate. Concluding that four-hole reconstruction plates provided insufficient stability, we modified subsequent designs to include more holes (

Figure 8), after which no additional complications occurred.

The use of patient-specific surgical guides and plates significantly improved both operative time efficiency and surgical predictability. As demonstrated in Case 1, successful reconstruction was achievable even in cases of previous reconstruction failure, validating the reliability of this approach. Furthermore, the use of surgical guides enhanced the accuracy of DCIA flap harvesting, minimizing donor site defects and enabling ideal bone segment acquisition. The plates eliminated the need for plate bending either preoperatively or intraoperatively, reducing the potential for fatigue fracture while enabling precise reconstruction[

20,

21,

22].

Steybe et al. conducted a landmark-based error analysis in 26 patients who underwent mandibular reconstruction using VSP-derived cutting and drilling jigs with patient-specific plates, reporting an average error of approximately 2 mm at key anatomical points including the condyle and gonion[

23]. In contrast, our study population included both segmental and marginal mandibulectomy cases, making landmark-based analysis less suitable. Therefore, we analyzed accuracy through direct comparison of preoperative plans with postoperative results, achieving higher accuracy with an average error of 0.73mm. Furthermore, our cases involved shorter average defect lengths (53.4 mm compared to 64.92 mm in Steybe et al.'s study[

23]) and were exclusively benign lesions, which likely contributed to improved accuracy. In a comparable study, Wang et al. analyzed 17 patients who underwent mandibular reconstruction using VSP-guided surgical templates and prebent reconstruction plates, employing a similar overlay analysis method to ours.[

24] They reported a mean error of 1.11 mm, which aligns closely with our accuracy findings. and Bhandari et al. performed error analysis through overlapping in mandibular reconstruction for category 1 and reported a mean error of 1.43 mm.[

25] However, this study has several limitations. First, the small sample size (5 cases) and absence of a control group limit the statistical significance of our findings. Second, the lack of long-term follow-up makes it difficult to evaluate long-term stability and potential complications. Third, the additional time and costs associated with manufacturing patient-specific devices must be considered. Future research should focus on accumulating more cases with long-term follow-up to validate the clinical efficacy of this technique. Additionally, standardization of protocols to minimize errors in virtual surgical planning is needed, as is research into optimal customized plate design, as evidenced by our modification following the screw loosening incident. Since SLM-printed customized plates cannot be modified intraoperatively, strategies for managing unexpected intraoperative variables need to be developed. With advances in 3D printing technology and reduced manufacturing costs, this technique may become more widely applicable.

5. Conclusions

The use of patient-specific surgical guides and plates in mandibular reconstruction using DCIA free flaps proves to be a valuable method for improving surgical accuracy and predictability. Our results demonstrate that digital approaches to mandibular reconstruction can be effectively applied to DCIA free flaps. Further research in this area will contribute to achieving more aesthetic and functionally successful mandibular reconstructions.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.Y.M and H.J.K.; methodology, H.J.K.; software, S.Y.M and H.J.K.; validation, J.S.O. and H.J.K; formal analysis, H.J.K.; investigation, H.J.K.; resources, S.Y.M.; data curation, H.J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.M., and J.S.O. ; visualization, H.J.K.; supervision, S.Y.M. and J.S.O.; project administration, S.Y.M.; funding acquisition, S.Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

“This work was supported by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology grant funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy in 2023 (Project: Support for Musculoskeletal Human Body Simulation Convergence Technology Based on Clinical Data)”

Institutional Review Board Statement

: “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chosun University Dental Hospital (CUDHIRB 2311 004 and Nov 22, 2023).”

Informed Consent Statement

“Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper”

Data Availability Statement

Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

References

- Kumar, B.P.; Venkatesh, V.; Kumar, K.J.; Yadav, B.Y.; Mohan, S.R. Mandibular reconstruction: overview. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery 2016, 15, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, W.; Loscalzo, L.J.; Baek, S.M.; Biller, H.F.; Krespi, Y.P. Experience with immediate and delayed mandibular reconstruction. The Laryngoscope 1982, 92, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Zagalo, C.M.; Oliveira, M.L.; Correia, A.M.; Reis, A.R. Mandible reconstruction: History, state of the art and persistent problems. Prosthetics and orthotics international 2015, 39, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Hindocha, N.; Thor, A. Time matters - Differences between computer-assisted surgery and conventional planning in cranio-maxillofacial surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2020, 48, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirke, D.N.; Owen, R.P.; Carrao, V.; Miles, B.A.; Kass, J.I. Using 3D computer planning for complex reconstruction of mandibular defects. Cancers Head Neck 2016, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.W.; Shan, X.F.; Lu, X.G.; Cai, Z.G. Preliminary clinic study on computer assisted mandibular reconstruction: the positive role of surgical navigation technique. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 2015, 37, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupret-Bories, A.; Vergez, S.; Meresse, T.; Brouillet, F.; Bertrand, G. Contribution of 3D printing to mandibular reconstruction after cancer. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2018, 135, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell'Aversana Orabona, G.; Abbate, V.; Maglitto, F.; Bonavolonta, P.; Salzano, G.; Romano, A.; Reccia, A.; Committeri, U.; Iaconetta, G.; Califano, L. Low-cost, self-made CAD/CAM-guiding system for mandibular reconstruction. Surg Oncol 2018, 27, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosetti, E.; Tos, P.; Berrone, M.; Battiston, B.; Arrigoni, G.; Succo, G. Long-Term Follow-Up of Computer-Assisted Microvascular Mandibular Reconstruction: A Retrospective Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascha, F.; Winter, K.; Pietzka, S.; Heufelder, M.; Schramm, A.; Wilde, F. Accuracy of computer-assisted mandibular reconstructions using patient-specific implants in combination with CAD/CAM fabricated transfer keys. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017, 45, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Wang, C.; Mao, C.; Lu, M.; Ouyang, Q.; Fang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Chen, W. Mandible reconstruction with free fibula flaps: Accuracy of a cost-effective modified semicomputer-assisted surgery compared with computer-assisted surgery - A retrospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2022, 50, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ince, B.; Ismayilzade, M.; Dadaci, M.; Zuhal, E. Computer-Assisted versus Conventional Freehand Mandibular Reconstruction with Fibula Free Flap: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020, 146, 686e–687e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, B.-Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Jung, J.; Ohe, J.-Y.; Eun, Y.-G.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.-W. Computer-Assisted Preoperative Simulations and 3D Printed Surgical Guides Enable Safe and Less-Invasive Mandibular Segmental Resection: Tailor-Made Mandibular Resection. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deek, N.; Wei, F.C. Computer-Assisted Surgery for Segmental Mandibular Reconstruction with the Osteoseptocutaneous Fibula Flap: Can We Instigate Ideological and Technological Reforms? Plast Reconstr Surg 2016, 137, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Sambrook, P.; Munn, Z.; Boase, S. Effectiveness of computer-assisted virtual planning, cutting guides and pre-engineered plates on outcomes in mandible fibular free flap reconstructions: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2019, 17, 2136–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, S.; Ricotta, F.; Maiolo, V.; Savastio, G.; Contedini, F.; Cipriani, R.; Bortolani, B.; Cercenelli, L.; Marcelli, E.; Marchetti, C.; et al. Computer-assisted surgery for reconstruction of complex mandibular defects using osteomyocutaneous microvascular fibular free flaps: Use of a skin paddle-outlining guide for soft-tissue reconstruction. A technical report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2019, 47, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, I.G.; Townsend, P.; Corlett, R. Superiority of the deep circumflex iliac vessels as the supply for free groin flaps: experimental work. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1979, 64, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modabber, A.; Mohlhenrich, S.C.; Ayoub, N.; Hajji, M.; Raith, S.; Reich, S.; Steiner, T.; Ghassemi, A.; Holzle, F. Computer-Aided Mandibular Reconstruction With Vascularized Iliac Crest Bone Flap and Simultaneous Implant Surgery. J Oral Implantol 2015, 41, e189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, P.; Eckert, A.W.; Kriwalsky, M.S.; Schubert, J. Scope and limitations of methods of mandibular reconstruction: a long-term follow-up. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2010, 48, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutwald, R.; Jaeger, R.; Lambers, F.M. Customized mandibular reconstruction plates improve mechanical performance in a mandibular reconstruction model. Computer methods in BiomeChaniCs and BiomediCal engineering 2017, 20, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, C.P.; Smolka, W.; Giessler, G.A.; Wilde, F.; Probst, F.A. Patient-specific reconstruction plates are the missing link in computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction: A showcase for technical description. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015, 43, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Liang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Song, S.; Jiang, C. Deviation Analyses of Computer-Assisted, Template-Guided Mandibular Reconstruction With Combined Osteotomy and Reconstruction Pre-Shaped Plate Position Technology: A Comparative Study. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 719466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steybe, D.; Poxleitner, P.; Metzger, M.C.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Russe, M.F.; Fuessinger, M.A.; Brandenburg, L.S.; Voss, P.J.; Schlager, S. Analysis of the accuracy of computer-assisted DCIA flap mandibular reconstruction applying a novel approach based on geometric morphometrics. Head & neck 2022, 44, 2810–2819. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-d.; Ma, W.; Fu, S.; Zhang, C.-b.; Cui, Q.-y.; Peng, C.-b.; Wang, S.-h.; Li, M. Application of digital guide plate with drill-hole sharing technique in the mandible reconstruction. Journal of Dental Sciences 2023, 18, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, K.; Lin, C.-H.; Liao, H.-T. Secondary mandible reconstruction with computer-assisted-surgical simulation and patient-specific pre-bent plates: the algorithm of virtual planning and limitations revisited. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).