1. Introduction

Mandibular reconstruction after tumor resection is one of the most challenging procedures in oral and maxillofacial surgery [

1]. The complex 3D anatomy of the mandible and its critical role in esthetics, mastication, and phonation require high-precision reconstruction to restore form and function [

2]. Several methods have been developed for mandibular reconstruction, each with its own advantages and limitations. Autologous bone grafts include non-vascularized grafts from the iliac crest, rib, or calvarium. While they are easy to harvest, they are limited in size and may have high resorption rates for larger defects. Vascularized free flaps have become the gold standard for large mandibular defects. Common donor sites include the fibula, iliac crest, scapula, and radial forearm. Each donor site has specific advantages in terms of bone stock, soft tissue availability, and donor site morbidity [

3,

4,

5].

Traditionally, surgeons have relied on their experience and intraoperative judgment to harvest and position bone grafts. However, this approach can result in unfavorable esthetic and functional outcomes. More recently, the advent of virtual surgical planning and 3D printing technologies has revolutionized the approach to mandibular reconstruction [

6,

7,

8]. These technologies offer the potential for increased accuracy, shorter operative times, and improved patient outcomes. CAD/CAM technology allows for detailed preoperative planning based on high-resolution CT images. This allows surgeons to accurately plan resection margins, design customized bone grafts, and digitally simulate mandibular reconstruction before surgery [

8].

The virtual surgical planning process involves a number of sophisticated steps. First, high-resolution CT scans of the patient’s mandible and potential donor site, such as the iliac crest [

9], are transformed into intricate three-dimensional renderings [

10]. Using state-of-the-art software, surgeons meticulously perform a virtual tumor resection, create an optimal reconstructive design, and delineate the exact dimensions and contours of the required bone graft. This advanced level of preoperative planning not only maximizes donor bone utilization, but also ensures superior congruency of the reconstructed mandible segment.

In addition, the ability to create patient-specific cutting and positioning guides through additive manufacturing represents a paradigm shift in the translation of virtual surgical plans to the surgical field. These customized guides serve as exquisite templates for mandibular resection and bone graft procurement, ensuring a high degree of fidelity between the virtual plan and the actual surgical procedure. The use of these meticulously crafted guides has demonstrably shortened intraoperative decision-making processes and significantly improved the precision of mandibular reconstruction.

Recent studies have demonstrated the benefits of computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction. These benefits include increased precision of osteotomies, decreased operative time, and improved esthetic outcomes. Empirical studies have shown that computer-guided techniques can achieve reconstructions with an accuracy of 1-2 mm relative to the virtual plan, a level of precision that remains elusive with conventional methods. Furthermore, the implementation of virtual planning and three-dimensional printed surgical guides has been associated with reduced ischemia time for free flaps, potentially leading to improved flap survival rates [

14,

15].

Despite these benefits, computer-aided reconstruction is not without its challenges. Implementation of this approach requires specialized software, expertise in virtual surgical planning, and access to additive manufacturing technology. In addition, there is a significant learning curve associated with integrating these advanced technologies into established surgical practices. The additional cost and time required for preoperative planning must also be weighed against the potential benefits of these techniques [

16,

17].

The complexity and time-intensive nature of computer-aided mandibular reconstruction, coupled with the steep learning curve for surgeons, underscores the critical need for collaboration between oral and maxillofacial surgeons and bioengineers. While surgeons have the clinical expertise and understanding of patient-specific needs, bioengineers bring specialized knowledge in 3D modeling, computer-aided design, and additive manufacturing processes. This interdisciplinary collaboration can significantly reduce the burden on surgeons, allowing them to focus on critical clinical decisions while utilizing the technical expertise of bioengineers [

18].

Bioengineers can play a critical role in various stages of the virtual surgical planning process, from the initial segmentation of CT scans and creation of 3D models to the design and optimization of patient-specific cutting and positioning guides. Their expertise can ensure the technical accuracy and manufacturability of these guides, potentially reducing errors and improving the overall efficiency of the surgical procedure. In addition, bioengineers can contribute to the continuous improvement of the virtual planning process by incorporating the latest advances in software and manufacturing technologies. The synergy between surgical expertise and bioengineering skills has the potential to overcome many of the challenges associated with computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction. By establishing a structured collaborative protocol, surgical teams can more effectively integrate these advanced technologies into their practice, potentially leading to improved patient outcomes, reduced operative times, and more predictable esthetic and functional results.

This paper aims to address the need for such collaboration by proposing an efficient working protocol between surgeons and bioengineers in the process of virtual surgical planning for mandibular reconstruction. By detailing the workflow, leveraging cloud-based collaboration software for efficient collaboration, and highlighting key decision points where interdisciplinary expertise is most beneficial, this study aims to provide a blueprint for effective collaboration that improves the quality of patient care and makes advanced reconstructive techniques more accessible to the broader surgical teams.

2. Virtual Surgical Planning Protocol Between Surgeons and Bioengineers

Generation of 3D Models

Accurate segmentation of the mandible and lesions from CBCT data to create STL files is critical for both precise surgical guide fabrication and accurate surgical planning. To take full advantage of virtual surgical planning, which provides a three-dimensional understanding of anatomical structures and lesions, it is necessary to segment not only the external shape of the mandible and lesions, but also anatomical structures such as tooth roots and inferior alveolar nerve bundles. However, these processes are time consuming.

Hounsfield unit slices are used to segment the mandible and surrounding anatomical structures for virtual surgical planning. The resulting 3D mandibular model, while too large for computer-aided design due to the inclusion of internal bone structures, is advantageous for virtual surgical planning because it allows simultaneous visualization of anatomical structures such as tooth roots and the inferior alveolar nerve bundle. For computer-aided planning, a 3D model of the mandible focused on the cortical bone area without inappropriate holes is preferred, and this task is best performed by a bioengineer.

Lesion segmentation is the most critical aspect of virtual surgical planning materials. Accurate lesion identification and appropriate safety margin setting are essential to reduce the risk of recurrence and minimize deviations from the plan during actual surgery. Therefore, lesion segmentation should be performed by the surgeon. This allows identification of ambiguous areas in the lesion and can be supplemented with other medical imaging data such as MRI or PET-CT. It also assists in setting resection margins during virtual surgery planning.

Surgeon’s role: Provide high quality CT scans, identify critical anatomical structures, segment lesions.

Bioengineer’s role: Segment CT data to create accurate 3D models of the mandible.

Setting the Resection Margin

The surgeon sets the resection margin based on the HU threshold-based mandible model and the lesion model. Adding a safety margin offset to the 3D lesion model can assist in setting the resection margin. The HU threshold-based mandibular model, including internal bone structures, is critical in determining whether to preserve or sacrifice adjacent teeth and the inferior alveolar nerve. It also allows the surgical approach (intraoral or submandibular) to be determined and instrument accessibility to be considered. This three-dimensional approach to structures and lesions allows planning of a safe yet conservative resection margin. Saving the resection margin as a plane is beneficial for subsequent reconstruction planning and collaboration between the surgeon and the bioengineer.

Surgeon’s role: Define resection margins based on clinical judgment and 3D visualization.

Bioengineer’s role: Implement resection margins in the 3D model, highlight potential problems.

Reconstruction Planning

Based on the established resection margin, a plan is developed to reconstruct the defect area. This process requires close collaboration between the surgeon and Bioengi-neer, led by the surgeon. The surgeon can formulate a surgical plan considering the length, width, height and shape of the defect area, as well as potential donor sites such as fibular or iliac crest free flaps. A partial osteotomy of the bone flap may be necessary given the curvature of the defect area, and the characteristics of the soft tissue flap and the position of the donor site’s supply vessels should also be considered.

The surgeon provides the overall direction for reconstruction based on clinical experience and anatomical knowledge, while the bioengineer implements and fine-tunes this in 3D software. The final reconstruction plan is determined through several rounds of feedback and modifications.

Surgeon’s role: Select donor site and determine overall direction of reconstruction

Bioengineer’s role: Fine-tune and optimize the reconstruction plan

Fabrication of Surgical Guides

Surgical guide fabrication is the final stage of virtual surgical planning and is critical to the accurate execution of the plan during the actual surgery. Surgical guides can be broadly categorized into mandibular resection guides and reconstruction guides. This process can be performed by the bioengineer under the guidance of the surgeon.

For the mandibular resection guide, the fitting area is determined considering the lesion characteristics and approach method. An extraoral approach can take advantage of the mandibular inferior border curvature, while an intraoral approach can benefit from alveolar bone adaptation. The Resection Guides can also be used to position the mandible by connecting the proximal and distal portions, and screw holes can be pre-set for accurate fitting of custom plates.

Reconstruction guides are fabricated with donor site characteristics in mind. Osteotomy lines for partial bone cuts and screw holes for accurate custom plate fitting are pre-set to ensure plate positioning according to the surgical plan.

Surgeon’s Role: Define the surgical approach and determine the overall shape of the surgical guide.

Bioengineer’s role: Design and 3D print patient-specific surgical guides.

Collaboration Software

The efficiency of surgeon-bioengineer collaboration was enhanced through a specialized software ecosystem. The surgeon primarily used Mimics software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) for initial segmentation and surgical planning, while bioengineers utilized Reconeasy software(SEEANN solution, Seoul, Korea) for design optimization. Data exchange occurred through standardized STL files, ensuring compatibility across platforms.

A key innovation in the workflow was the implementation of Reconeasy Collabo, a cloud-based collaboration platform. This software enabled:

1. Real-time 3D visualization of surgical plans on both computers and mobile devices

2. Asynchronous communication through embedded commenting systems

3. Version control of design iterations

4. Remote accessibility for all team members

3. Simulation of Surgeon-Bioengineer Collaboration

To validate the efficiency of our protocol, simulations mirroring actual patient surgery schedules were conducted. When the actual surgical schedule of a patient requiring mandibular reconstruction surgery among the patients visiting Chosun University Dental Hospital was set, a simulation was performed based on the patient’s medical image data and surgical plan. Seven simulations were performed, tracking the duration and number of redesign iterations required. All collaborations took place between the same surgeon team and bio-engineer team (

Table 1).

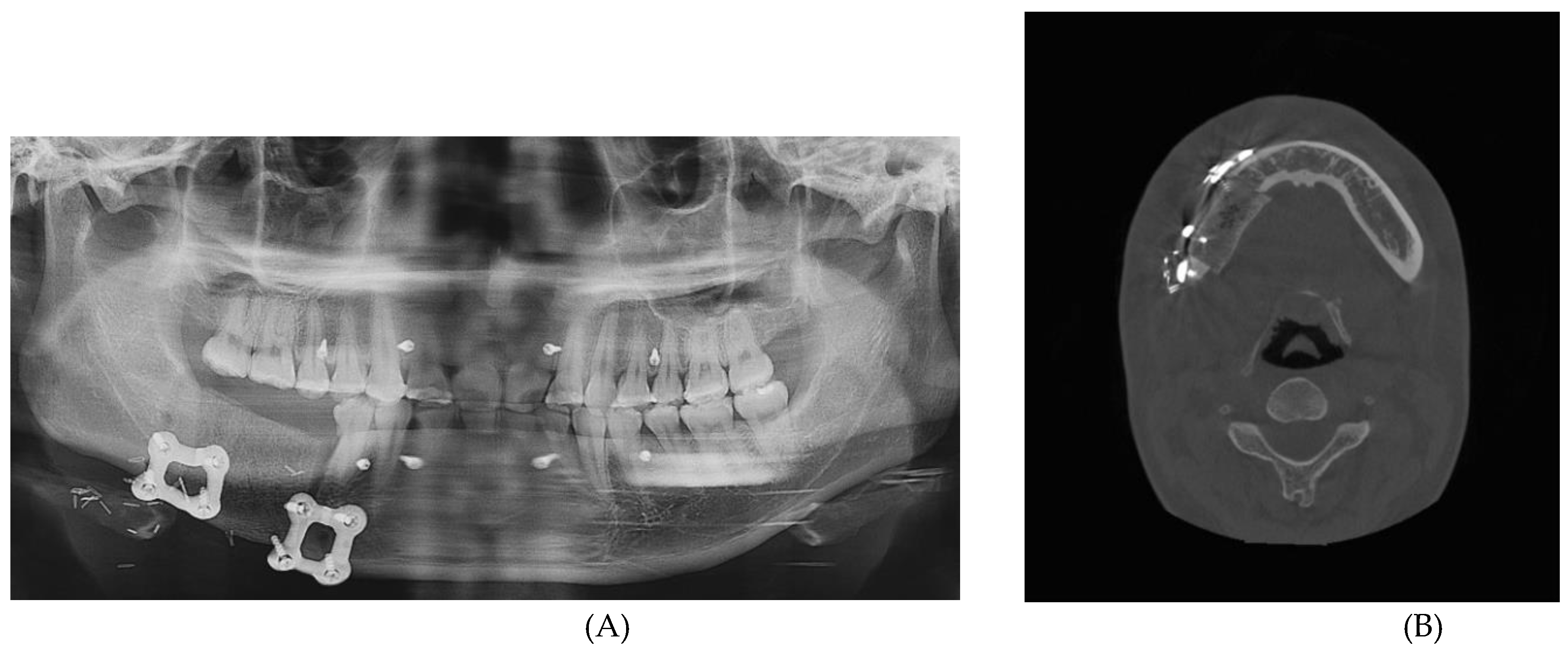

4. Case Presentation

A 25-year-old female was referred to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery from a local dental clinic with a primary concern of an intraosseous lesion located below the root apex of the right mandibular first molar. The patient did not report any clinical symptoms. Panorex revealed a multilocular radiolucent lesion with relatively well defined borders and sclerotic margins in the region of the right mandibular molar. In addition, root resorption was observed in the right mandibular second premolar and first molar (

Figure 1). Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) revealed thinning of the lingual cortical bone in the areas surrounding the right mandibular second premolar and first molar, as well as inferior displacement of the right mandibular canal (

Figure 2). Both the right mandibular second premolar and first molar exhibited slight mobility and percussion sensitivity, while electric pulp testing was positive. Incisional biopsy was the ameloblastoma. To treat the lesion and minimize the risk of recurrence, resection and reconstruction were planned, and virtual surgical planning was performed in collaboration with SEEANN solution (SEEANN solution, Seoul, Korea).

Generation of 3D Models

Based on CBCT DICOM data, the surgeon created a mandible 3D model based on HU threshold using mimics software(Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) and segmented the lesion to create a 3D model (

Figure 3-A). SEEANN solution created a mandible 3D model using its self-developed reconeasy software (

Figure 5).

Setting the Resection Margin

The surgeon planned a osteotomy based on the size and aggressiveness of the lesion and determined the resection margin (

Figure 3-B). The relevant data was transferred to the bioengineer with Reconeasy collabo (Seeann Solution Co., Ltd., South Korea), a cloud-based collaboration software.

Reconstruction Planning

Given the length of the resected mandible, reconstruction with a DCIA flap was planned. In collaboration with a bioengineer, the area that could reproduce the natural curvature of the mandible while minimizing donor site morbidity was planned (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Fabrication of Surgical Guides

Surgical guide was fabricated by making full cover of the inferior border of the mandible. In addition, the mesial resection guide and the distal resection guide were connected to each other for fabrication so that they could be used as positioning guides for the mandible. The design and control of the guide was done in close collaboration between the surgeon and the bioengineer using Reconeasy collabo software (

Figure 5). The patient-specific plate was also fabricated.

Figure 3.

3D modeling image of the mandible , segmented lesion, and determining the resection margin.

Figure 3.

3D modeling image of the mandible , segmented lesion, and determining the resection margin.

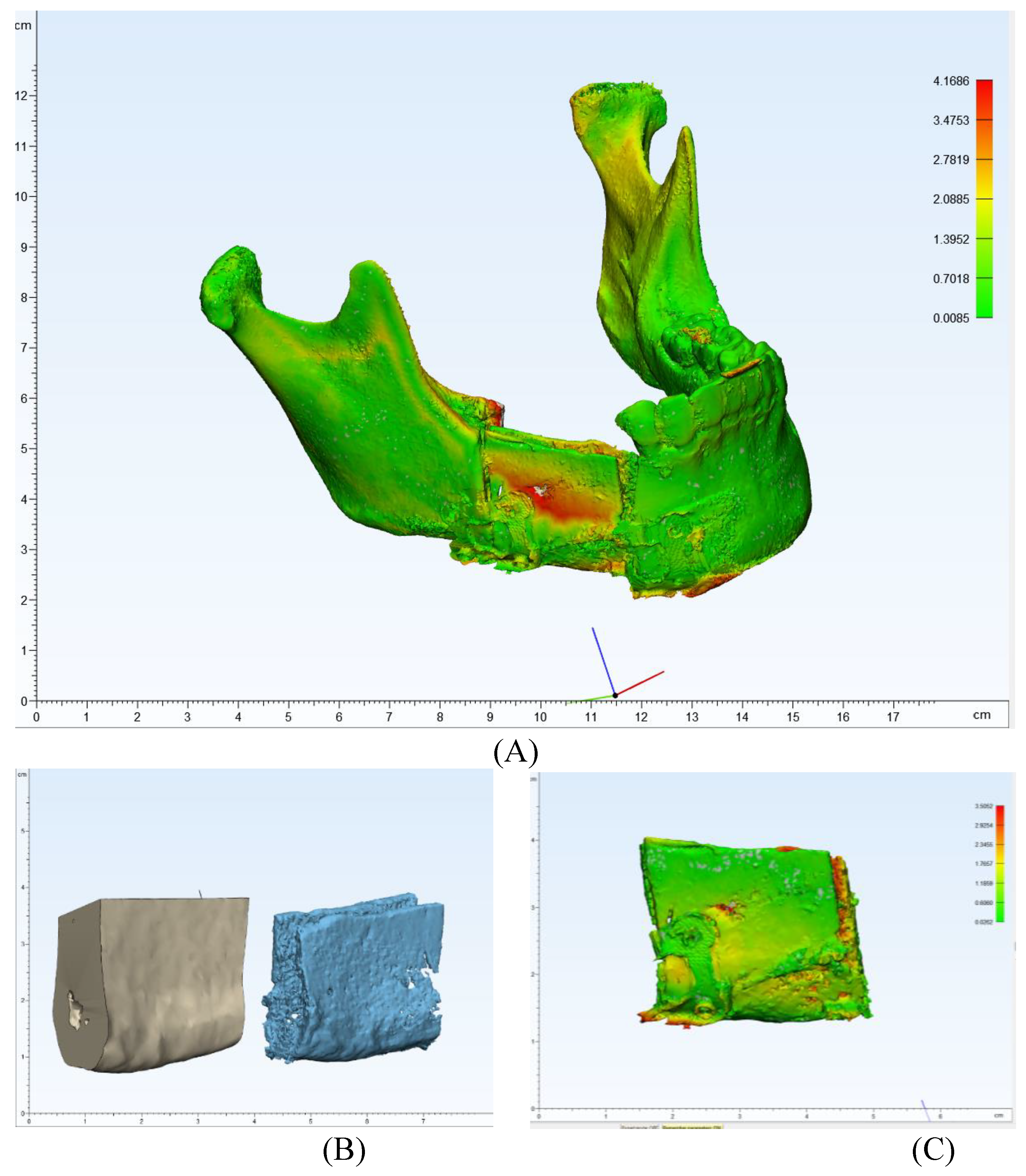

Figure 4.

The mandibular and iliac bone images were merged to design an iliac flap corresponding to the tumor resection margins.

Figure 4.

The mandibular and iliac bone images were merged to design an iliac flap corresponding to the tumor resection margins.

Figure 5.

Surgical guides for tumor resection and iliac flap harvesting were fabricated.

Figure 5.

Surgical guides for tumor resection and iliac flap harvesting were fabricated.

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. #45, 46, and 47 were extracted. Segmental mandibulectomy was performed using a surgical guide through a submandibular approach. (

Figure 6). The left iliac crestal DCIA flap was harvested according to the surgical guide. (

Figure 7) To minimize the morbidity of the donor site , The donor site was reconstructed using titanium mesh and allobone chip graft. (

Figure 8) Microvascular anastomosis was performed using the facial artery and facial vein. Fixation of the resected mandible and the bicortical iliac bone flap was achieved using a customized reconstruction plate (Cusmedi ©, Sungnam, Korea) designed to have a thickness of 2 to 3 mm according to the patient’s mandibular morphology and the periphery of the iliac bone flap and 3D printed by the selective laser melting (SLM) method, and eight 2.3-mm reconstruction screws. (

Figure 9). Silastic drain was inserted into the submandibular region and sutured. (

Figure 10) The final diagnosis was Ameloblastoma.

Postoperative panoramic radiograph and CBCT imaging was obtained to evaluate the error compared to the preoperative plan. (

Figure 11) The evaluation was performed using Materialize 3-matic software. After aligning the preoperative plan STL model and the postoperative STL model, the average value was obtained through analysis of the difference between the two models. the average discrepancy was 0.79 mm.

4. Results

Four mandibular reconstruction surgeries were performed, including the cases described above. The details of each case are summarized in

Table 2. The preoperative planning and postoperative results were evaluated in the same manner as described above and summarized in

Table 3.

5. Discussion

Analysis of the simulation data showed that the mean time for the virtual surgery planning process was 2.86 working days (standard deviation 1.35 days). This suggests that in most cases the planning can be completed within 3 days. Of note, only 2 of the 7 simulations required redesign iterations, which is an indicator of the accuracy and efficiency of the initial plan. In addition, a trend of increasing efficiency was observed over time. Later simulations generally required fewer working days, which seems to reflect the learning curve of the team and the gradual improvement of the protocol. This trend demonstrates the potential for the surgeon-bioengineer collaboration protocol to become more efficient over time. The results of this analysis suggest that the proposed collaboration protocol is efficient and can be operated within a time frame applicable to real-world clinical settings. It also demonstrates the potential for the process to become more efficient as the team gains experience.

This case report demonstrates the successful implementation of a proposed collaborative protocol between surgeons and bioengineers in virtual surgical planning for mandibular reconstruction. The results highlight several key benefits of this interdisciplinary approach, while also identifying areas for potential improvement and further research.

One of the primary benefits observed in this case was the high level of precision achieved in the reconstruction. Postoperative panoramic radiographs and cone beam CT scans showed that the actual reconstruction closely matched the virtual surgical plan (

Figure 7 A-B). When comparing the overall preoperative and postoperative results, the average discrepancy was 0.90mm. This level of accuracy is consistent with findings in the literature, where studies have reported average differences between virtual plans and postoperative results ranging from 0.9 mm to 3.0 mm [

9,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The ability to achieve this level of accuracy is critical for restoring both esthetics and function, particularly in terms of dental rehabilitation and temporomandibular joint alignment..

While virtual surgical planning and guided surgery improve accuracy and reduce operative time, especially flap ischemic time [

13,

28], they require greater expertise and preoperative planning. The proposed collaborative protocol demonstrated significant time savings in preoperative planning. The clear division of tasks between surgeons and bioengineers allowed parallel workflows, optimizing the overall process. Surgeons focused on critical clinical decisions, while bioengineers handled the technical aspects of 3D modeling and guide fabrication. This efficient use of expertise not only reduced operative time, but also potentially reduced the risk of surgical complications associated with prolonged procedures.

The synergy between surgical expertise and bioengineering skills was particularly evident in the flap design phase. The surgeon’s understanding of the anatomical and functional requirements guided the bioengineer’s optimization of the virtual flap design. This collaboration resulted in a flap that minimized the need for intraoperative adjustments by maximizing the natural contour of the iliac crest.

The implementation of this collaborative protocol demonstrated the importance of clear communication and mutual understanding between surgeons and bioengineers. While there was an initial learning curve in adopting these techniques, team efficiency improved over time as each discipline became more familiar with the capabilities and limitations of the other. This underscores the need for ongoing interdisciplinary training and education to maximize the benefits of computer-assisted surgery.

The protocol aimed to optimize resource allocation by leveraging the unique skills of both surgeons and bioengineers. Although there are additional costs associated with virtual surgical planning and 3D printing, the improved outcomes and potential time savings justify the investment. However, a comprehensive cost-effectiveness analysis with a larger case series would be beneficial.

Despite the success of this case, several limitations of the current collaborative approach have been identified. The accuracy of the reconstruction still relies heavily on the precise placement of the cutting guides, which remains the responsibility of the surgeon. Future iterations of the protocol could explore ways for bioengineers to provide real-time assistance during guide placement, possibly through augmented reality technologies.

In addition, while the current protocol is excellent at addressing bony reconstruction, it does not fully address soft tissue considerations. Future collaborations could involve bioengineers in soft tissue analysis and planning, potentially improving overall esthetic outcomes.

While immediate postoperative results are promising, long-term follow-up is essential to assess the stability of the reconstruction and evaluate functional outcomes. This follow-up should include both surgical and bioengineering perspectives to continually refine the collaborative protocol. Future studies with larger patient cohorts and longer follow-up periods will be essential to fully understand the long-term benefits of this interdisciplinary approach to computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction.

6. Conclusions

This study reports the successful implementation of a collaborative protocol between surgeons and bioengineers for virtual surgical planning in mandibular reconstruction. The protocol resulted in high precision, with an average discrepancy of 0.90 mm between the virtual plan and the postoperative results. It enabled an efficient workflow, optimizing both preoperative planning and intraoperative procedures. The synergy between surgical and bioengineering expertise particularly benefited the flap design phase, minimizing the need for intraoperative adjustments. Although promising, this approach requires further validation through larger cohort studies and long-term follow-up to assess its full potential for improving surgical outcomes and cost-effectiveness in mandibular reconstruction.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.Y.M and H.J.K.; methodology, D.H.S.; software, D.H.S. and H.J.K.; validation, D.H.S., J.S.O. and H.J.K; formal analysis, D.H.S. and H.J.K.; investigation, D.H.S. and H.J.K.; resources, S.Y.M.; data curation, D.H.S. and H.J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.H.S.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.M., J.S.O. and H.J.K.; visualization, D.H.S.; supervision, S.Y.M. and J.S.O.; project administration, S.Y.M.; funding acquisition, S.Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“This research was funded by project for Industry-University-Research Institute platform cooperation R&D funded Korea Ministry of SMEs and Startups in 2022, grant number RS-2022-TI023679”

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chosun University Dental Hospital (CUDHIRB 2301 002 and May 25, 2023).”

Informed Consent Statement

“Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper”

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Lonie, S.; Herle, P.; Paddle, A.; Pradhan, N.; Birch, T.; Shayan, R. Mandibular reconstruction: meta-analysis of iliac- versus fibula-free flaps. ANZ Journal of Surgery 2016, 86, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, M.; Jacobson, A.S.; Buchbinder, D.; Urken, M.L. Contemporary reconstruction of the mandible. Oral Oncol 2010, 46, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.P.; Venkatesh, V.; Kumar, K.J.; Yadav, B.Y.; Mohan, S.R. Mandibular reconstruction: overview. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery 2016, 15, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, P.; Eckert, A.W.; Kriwalsky, M.S.; Schubert, J. Scope and limitations of methods of mandibular reconstruction: a long-term follow-up. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2010, 48, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.F.; Wushou, A.; Zheng, J.; Li, G. An alternative approach for mandible reconstruction. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2013, 24, e195–e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupret-Bories, A.; Vergez, S.; Meresse, T.; Brouillet, F.; Bertrand, G. Contribution of 3D printing to mandibular reconstruction after cancer. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2018, 135, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, D.L.; Garfein, E.S.; Christensen, A.M.; Weimer, K.A.; Saddeh, P.B.; Levine, J.P. Use of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing to produce orthognathically ideal surgical outcomes: a paradigm shift in head and neck reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009, 67, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, F.; Cornelius, C.P.; Schramm, A. Computer-Assisted Mandibular Reconstruction using a Patient-Specific Reconstruction Plate Fabricated with Computer-Aided Design and Manufacturing Techniques. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2014, 7, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modabber, A.; Mohlhenrich, S.C.; Ayoub, N.; Hajji, M.; Raith, S.; Reich, S.; Steiner, T.; Ghassemi, A.; Holzle, F. Computer-Aided Mandibular Reconstruction With Vascularized Iliac Crest Bone Flap and Simultaneous Implant Surgery. J Oral Implantol 2015, 41, e189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsitano, A.; Del Corso, G.; Ciocca, L.; Scotti, R.; Marchetti, C. Mandibular reconstructions using computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing: A systematic review of a defect-based reconstructive algorithm. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015, 43, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, M.; Crosetti, E.; Tos, P.L.; Pentenero, M.; Succo, G. Fibular osteofasciocutaneous flap in computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction: technical aspects in oral malignancies. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2016, 36, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deek, N.; Wei, F.C. Computer-Assisted Surgery for Segmental Mandibular Reconstruction with the Osteoseptocutaneous Fibula Flap: Can We Instigate Ideological and Technological Reforms? Plast Reconstr Surg 2016, 137, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirke, D.N.; Owen, R.P.; Carrao, V.; Miles, B.A.; Kass, J.I. Using 3D computer planning for complex reconstruction of mandibular defects. Cancers Head Neck 2016, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, B.; Yu, H.; Shen, S.G.; Wang, X. Evaluation of computer-assisted mandibular reconstruction with vascularized fibular flap compared to conventional surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016, 121, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maesschalck, T.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Scolozzi, P. Computer-assisted versus traditional freehand technique in fibular free flap mandibular reconstruction: a morphological comparative study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2017, 274, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, J.Y. The Pros and Cons of Computer-Aided Surgery for Segmental Mandibular Reconstruction after Oncological Surgery. Arch Craniofac Surg 2017, 18, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarsitano, A.; Battaglia, S.; Crimi, S.; Ciocca, L.; Scotti, R.; Marchetti, C. Is a computer-assisted design and computer-assisted manufacturing method for mandibular reconstruction economically viable? J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2016, 44, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, F.A.; Liokatis, P.; Mast, G.; Ehrenfeld, M. Virtual planning for mandible resection and reconstruction. Innov Surg Sci 2023, 8, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascha, F.; Winter, K.; Pietzka, S.; Heufelder, M.; Schramm, A.; Wilde, F. Accuracy of computer-assisted mandibular reconstructions using patient-specific implants in combination with CAD/CAM fabricated transfer keys. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017, 45, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschl, L.M.; Mucke, T.; Fichter, A.; Gull, F.D.; Schmid, C.; Duc, J.M.P.; Kesting, M.R.; Wolff, K.D.; Loeffelbein, D.J. Functional Outcome of CAD/CAM-Assisted versus Conventional Microvascular, Fibular Free Flap Reconstruction of the Mandible: A Retrospective Study of 30 Cases. J Reconstr Microsurg 2017, 33, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xi, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, M. Computer-Aided Design and Three-Dimensional-Printed Surgical Templates for Second-Stage Mandibular Reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg 2018, 29, 2101–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarsitano, A.; Battaglia, S.; Ricotta, F.; Bortolani, B.; Cercenelli, L.; Marcelli, E.; Cipriani, R.; Marchetti, C. Accuracy of CAD/CAM mandibular reconstruction: A three-dimensional, fully virtual outcome evaluation method. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2018, 46, 1121–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Baar, G.J.C.; Forouzanfar, T.; Liberton, N.; Winters, H.A.H.; Leusink, F.K.J. Accuracy of computer-assisted surgery in mandibular reconstruction: A systematic review. Oral Oncol 2018, 84, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S. A New Modified Method for Accurate Mandibular Reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018, 76, 1816–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, J.; Sun, Y.; Luebbers, H.T.; Bila, M.; Darche, V.; Politis, C. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing-Assisted Mandibular Reconstruction With a Fibula Free Flap. J Craniofac Surg 2019, 30, 2319–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingzhou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Ong, H.S.; Chenping, Z.; Abdelrehem, A. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing Surgical Template for Guidance of Dental Implant Distraction in Mandibular Reconstruction With Free Fibula Flaps. J Craniofac Surg 2020, 31, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetti, E.; Tos, P.; Berrone, M.; Battiston, B.; Arrigoni, G.; Succo, G. Long-Term Follow-Up of Computer-Assisted Microvascular Mandibular Reconstruction: A Retrospective Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieira Gil, R.; Roig, A.M.; Obispo, C.A.; Morla, A.; Pages, C.M.; Perez, J.L. Surgical planning and microvascular reconstruction of the mandible with a fibular flap using computer-aided design, rapid prototype modelling, and precontoured titanium reconstruction plates: a prospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015, 53, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyirjesy, S.C.; Heller, M.; von Windheim, N.; Gingras, A.; Kang, S.Y.; Ozer, E.; Agrawal, A.; Old, M.O.; Seim, N.B.; Carrau, R.L.; et al. The role of computer aided design/computer assisted manufacturing (CAD/CAM) and 3- dimensional printing in head and neck oncologic surgery: A review and future directions. Oral Oncol 2022, 132, 105976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).