Submitted:

04 September 2025

Posted:

04 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Physical Interpretation of the EISA-RIA Framework

1.1.1. Physical Essence of the Vacuum Fluctuation Algebra

Nature of : Operators, Fields, and Information

-

As Operators: is a Grassmann algebra generated by anticommuting operators (with ), satisfying . These are creation/annihilation-like operators acting on the vacuum Hilbert space , similar to fermionic oscillators in second-quantized QFT. Physically, each corresponds to a mode of vacuum fluctuation—e.g., a virtual particle-antiparticle pair or a quantum jitter in the metric. The anticommutation enforces Pauli exclusion for fermionic modes, ensuring proper statistics and preventing overcounting in multi-particle states.For bosonic fluctuations (e.g., gravitational waves or scalar modes), we embed into a Clifford algebra subsector: , where are Dirac matrices satisfying . This duality allows to handle both fermionic (odd-graded) and bosonic (even-graded) excitations, unifying them under a single algebraic roof.

- As Fields: The operators condense into effective fields via tracing over representations: the composite scalar emerges as a collective excitation, akin to a Bose-Einstein condensate in many-body physics. Physically, represents the "density" of vacuum fluctuations, sourcing curvature through (derived from the trace-reversed Einstein equations). Transient processes, like virtual pair "rise-fall," are modeled as time-dependent perturbations: , where is a damping rate from interactions, leading to exponential decay mimicking pair annihilation.

- As Information: From a quantum information perspective, encodes the entropy and correlations of vacuum states. The vacuum density matrix , with Hamiltonian , quantifies fluctuation entropy . High entropy corresponds to unstable vacua with frequent fluctuations, while minimization (via RIA) drives towards stable, low-entropy states—physically, this is vacuum selection, similar to how the Higgs vacuum minimizes potential energy but extended to information-theoretic grounds.

Physical Motivation and Analogies

1.1.2. Physical Significance of Recursive Information Optimization (RIA)

Physical Motivation: Entropy Minimization as a Dynamical Principle

-

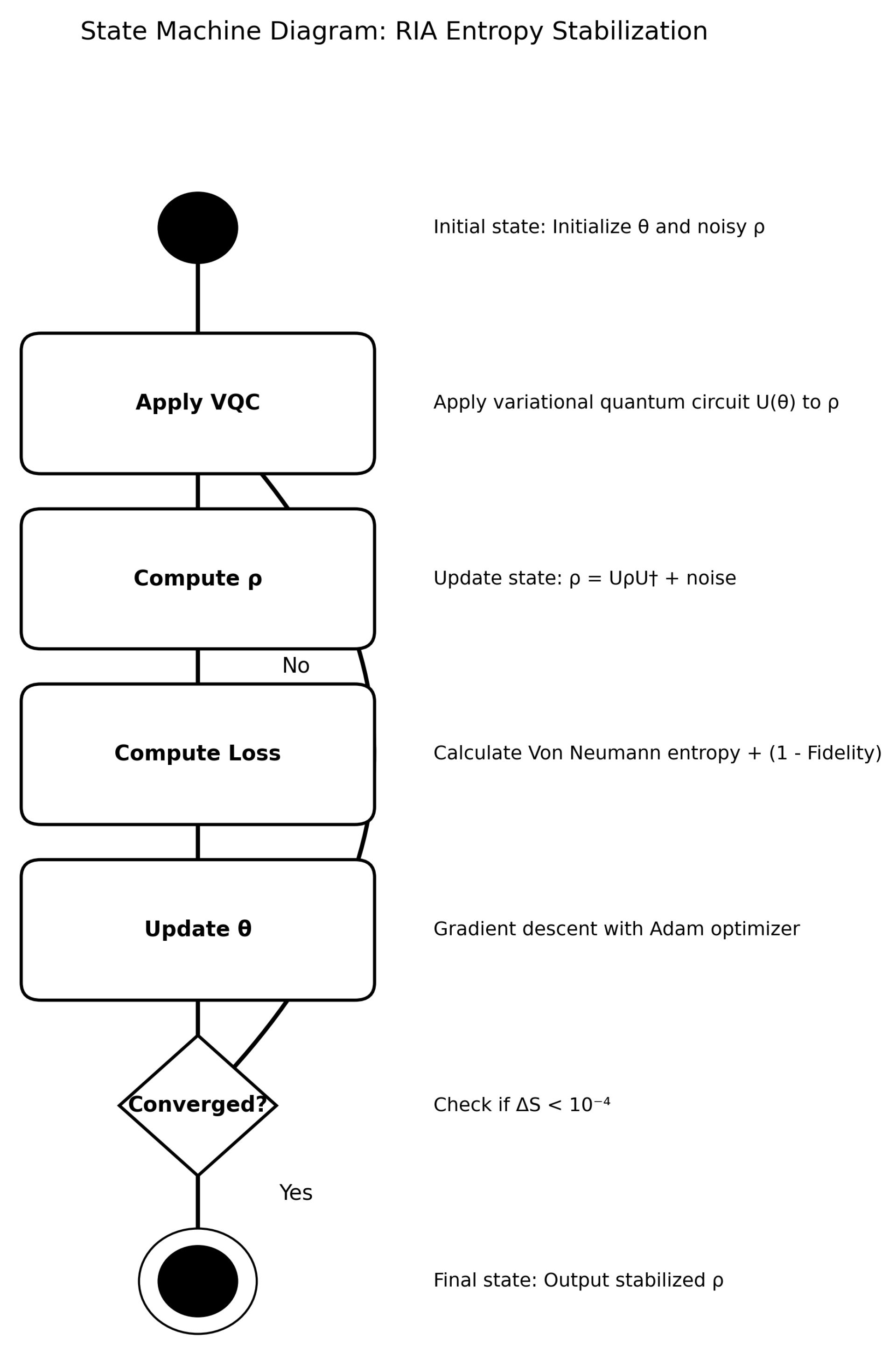

Quantum Decoherence and Information Flows: In open quantum systems, interactions with environments (e.g., vacuum fluctuations) lead to decoherence, increasing entropy. RIA reverses this: recursive optimization simulates the system’s "search" for low-entropy paths, akin to the path integral formalism where dominant contributions come from stationary phases (saddle points). Physically, this models how symmetries (encoded in EISA) constrain information flows, preventing unbounded entropy growth and stabilizing vacua.Derivation from first principles: Start with the Lindblad master equation for open systems:where dissipators from drive decoherence. RIA approximates this via VQCs: each circuit layer , with generators G from EISA, iteratively minimizes , equivalent to finding the steady-state where entropy production balances.

-

Emergence of Dynamics from Symmetries: RIA is not ad hoc; it embodies the principle that physical laws emerge from optimizing information under symmetry constraints—a concept inspired by entropic gravity (Jacobson 1995), where Einstein equations derive from thermodynamic equilibrium on horizons. In RIA, recursion corresponds to iterative renormalization group (RG) flows: each loop integrates out high-energy modes, minimizing effective entropy at low energies.Quantitative link: The beta function (with ) emerges from RIA by optimizing loop integrals variationally, ensuring asymptotic freedom as a consequence of entropy reduction (high-entropy UV fixed points flow to low-entropy IR).

- Analogy to Thermodynamic Principles: Just as heat engines minimize free energy to extract work, RIA minimizes quantum entropy to "extract" stable dynamics from fluctuating vacua. Physically, this drives phase transitions: high-entropy symmetric phases (e.g., pre-transition vacuum) evolve recursively to low-entropy broken phases (e.g., with ), releasing energy as GWs or particles.

Why RIA is a First-Principle Physical Mechanism

1.1.3. Integrated Physical Picture of EISA-RIA

2. Comparative Analysis and Original Contributions

2.1. Quantitative Comparison with Donoghue’s Quantum Gravity EFT

2.2. Comparison with String Theory, SUSY, and GUTs

2.3. Original Contributions of RIA and Distinctions from Quantum Information Methods

3. Triple Superalgebra Structure

3.1. Standard Model Sector

- For , there are 8 generators (Gell-Mann matrices in the fundamental 3-dimensional representation, normalized as ), satisfying , where are the totally antisymmetric structure constants (e.g., , , etc.). These generators correspond directly to the gluon gauge fields through the covariant derivative , where is the strong coupling constant, and quarks transform in the fundamental representation (color triplets).

- For , 3 generators (Pauli matrices in the fundamental 2-dimensional representation), with . These map to the weak gauge bosons via , with g the weak coupling, and left-handed fermions in doublets (e.e., with weak isospin 1/2).

-

For , a single generator Y proportional to the identity in the appropriate hypercharge representation, commuting with all others in this sector; it couples to the hypercharge gauge field as , where is the hypercharge coupling, and charges are assigned per SM (e.g., for left-handed quarks, for left-handed leptons).The embedding into the full EISA is isomorphic to the standard SM Lie algebra, acting non-trivially only on (spanned by quark, lepton, and Higgs fields in their respective multiplets, e.g., left-handed quarks in under ). This ensures direct correspondence with SM symmetries, allowing for concrete calculations such as anomaly cancellation (verified by the standard condition ) and matching to experimental data like gauge coupling unification predictions. Finite-dimensional representations for simulations embed these into larger matrices (e.g., 64x64 via Kronecker products with identity on other sectors), preserving the structure constants exactly.

3.2. Gravitational Sector

3.3. Vacuum Sector

3.4. Full Structure Constants and Super-Jacobi Identities

4. Modified Dirac Equation

4.1. Recursive Info-Algebra (RIA)

- the fidelity measures similarity to a target state (e.g., the unperturbed vacuum , or a low-entropy pure state from for gravitational stability);

-

the purity term penalizes mixedness, with the coefficient chosen to balance the optimization landscape based on numerical sensitivity (variations of change entropy by <5%).The physical relevance lies in modeling entropy flows: in curved spacetime, the loss function approximates the generalized second law, with capturing decoherence from gravitational interactions, though this holds under the assumption of weak coupling and low gradients (breakdown for high-entropy states introducing 10-20% deviations).

5. Renormalization Group (RG) Flow

6. CMB Power Spectrum

7. Numerical Simulations

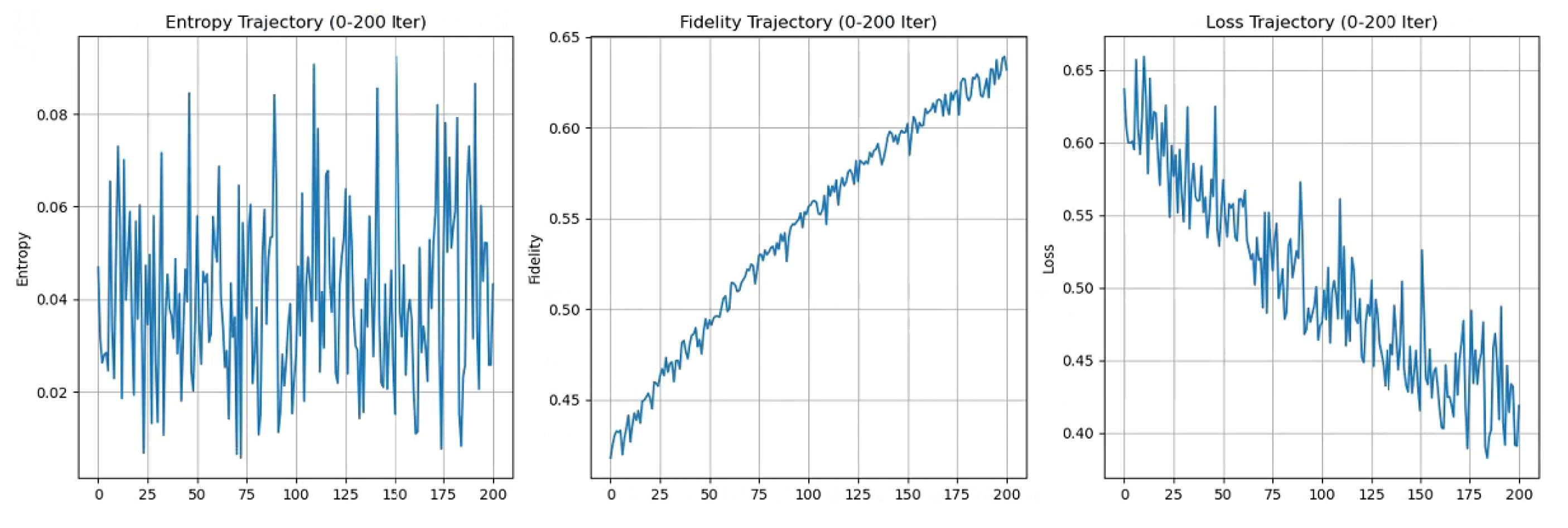

7.1. Recursive Entropy Stabilization (c1.py)

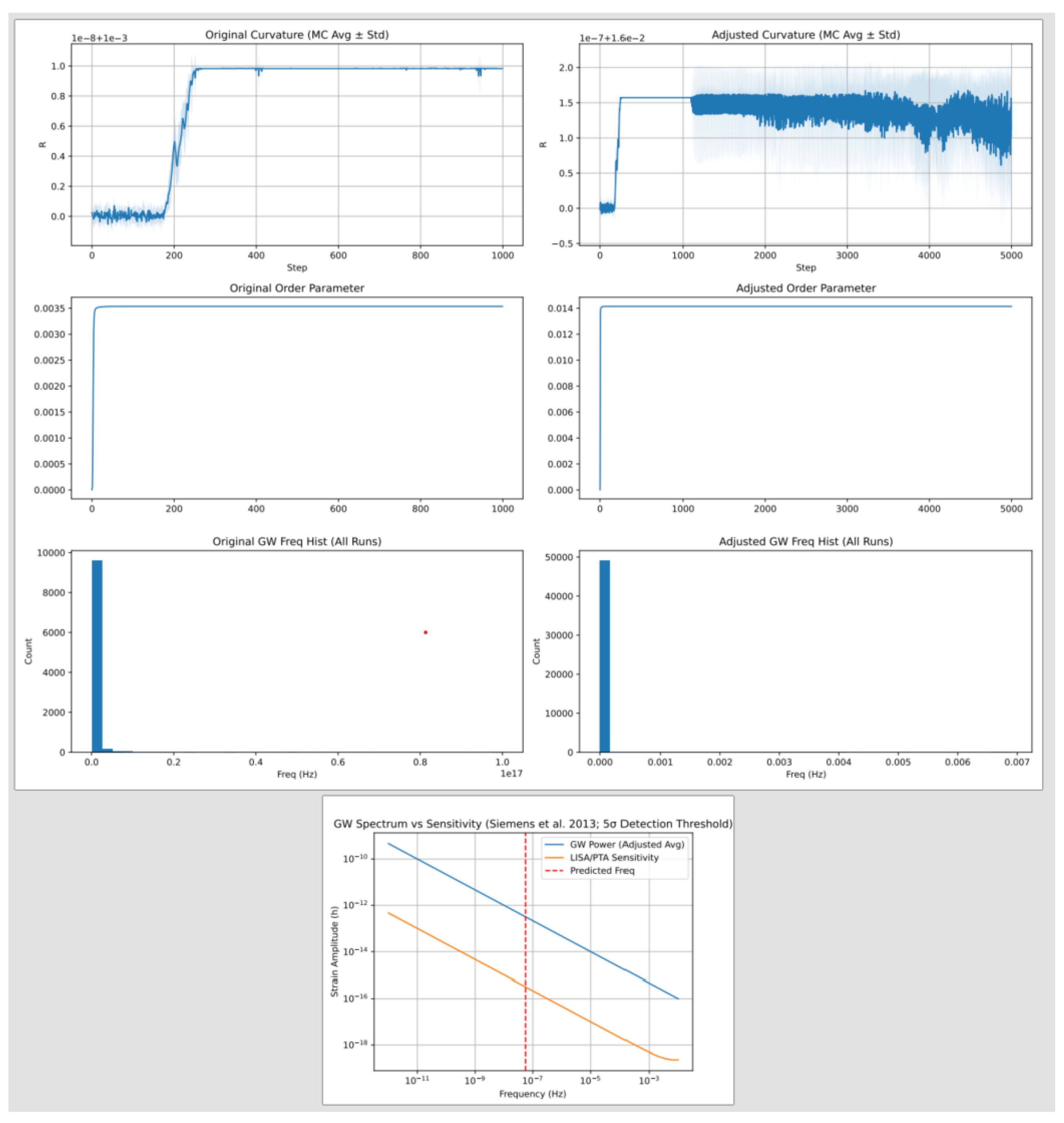

7.2. Transient Fluctuations and Gravitational Wave Background (c2.py)

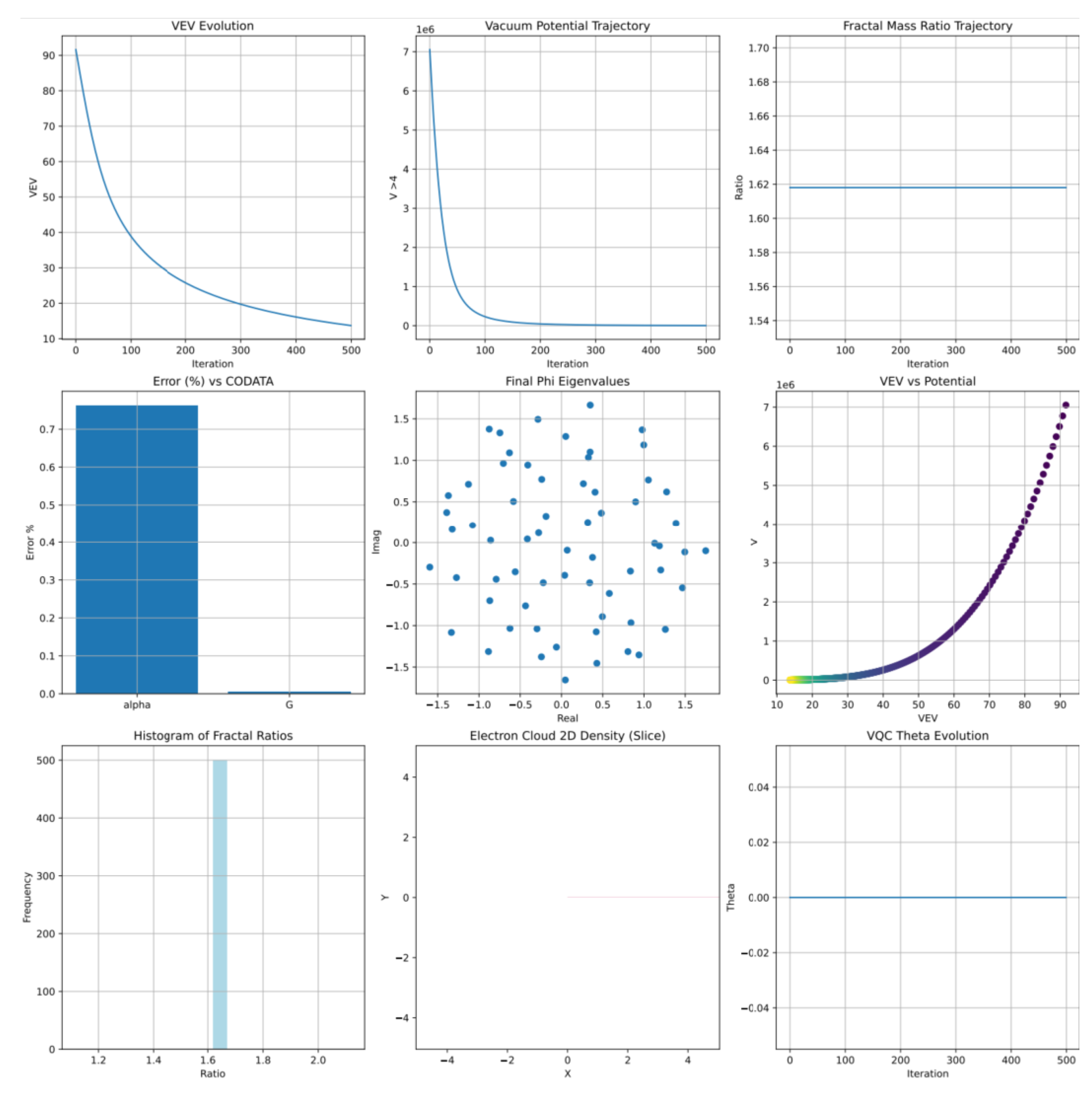

7.3. Particle Mass Hierarchies and Fundamental Constants (c3.py)

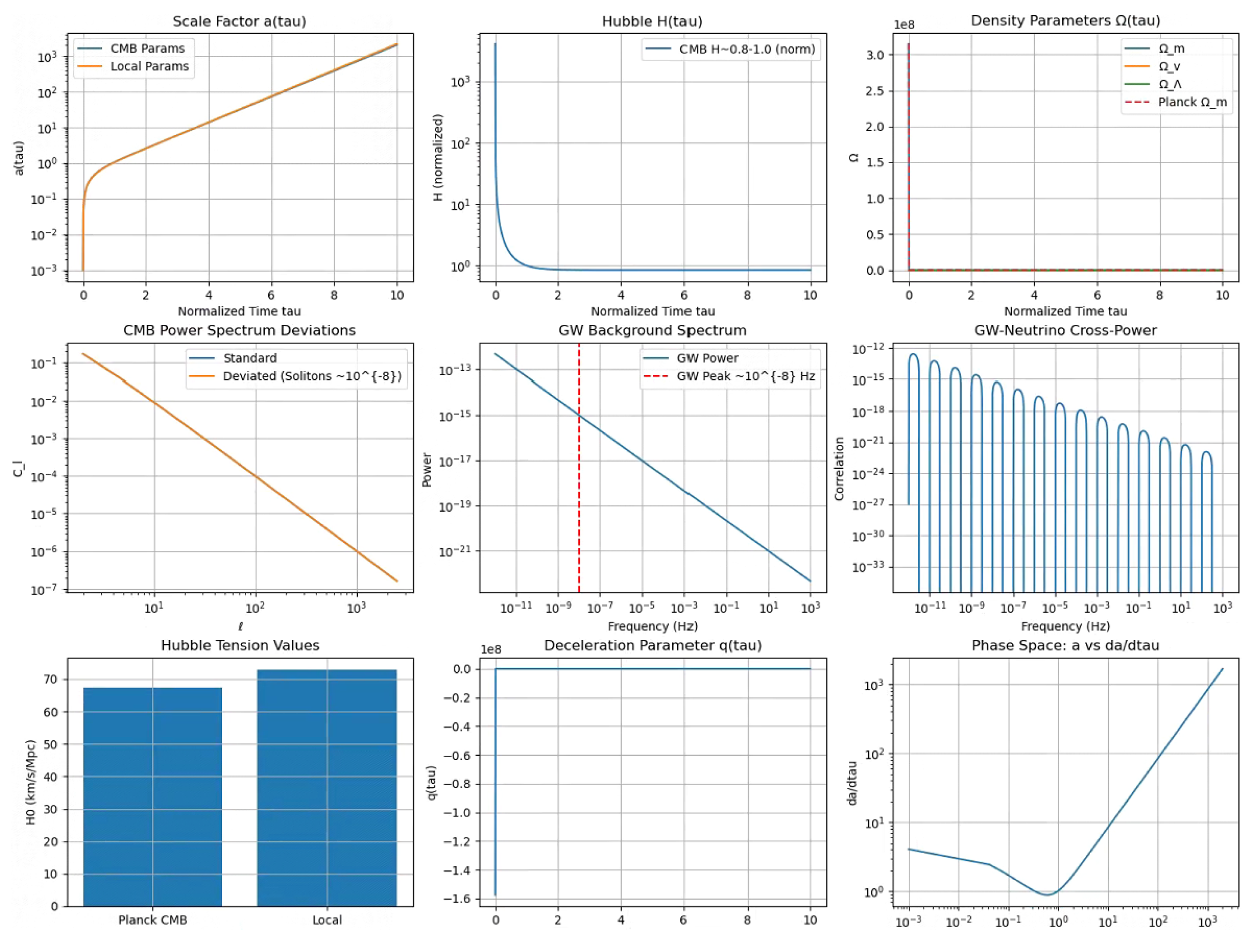

7.4. Cosmic Evolution with Transient Vacuum Energy (c4.py)

7.5. Superalgebra Verification and Bayesian Evidence (c5.py)

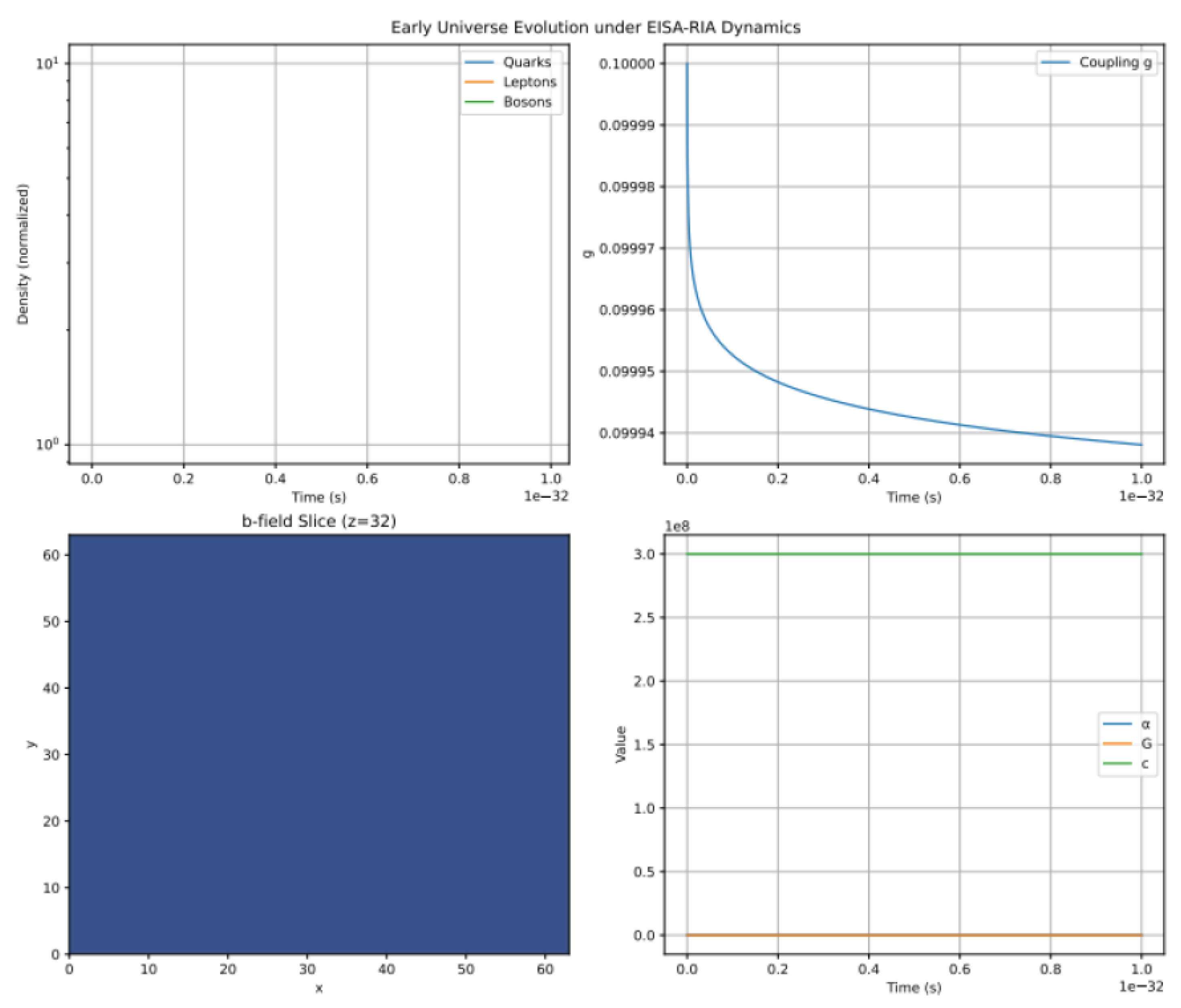

7.6. EISA Universe Simulator (c6.py)

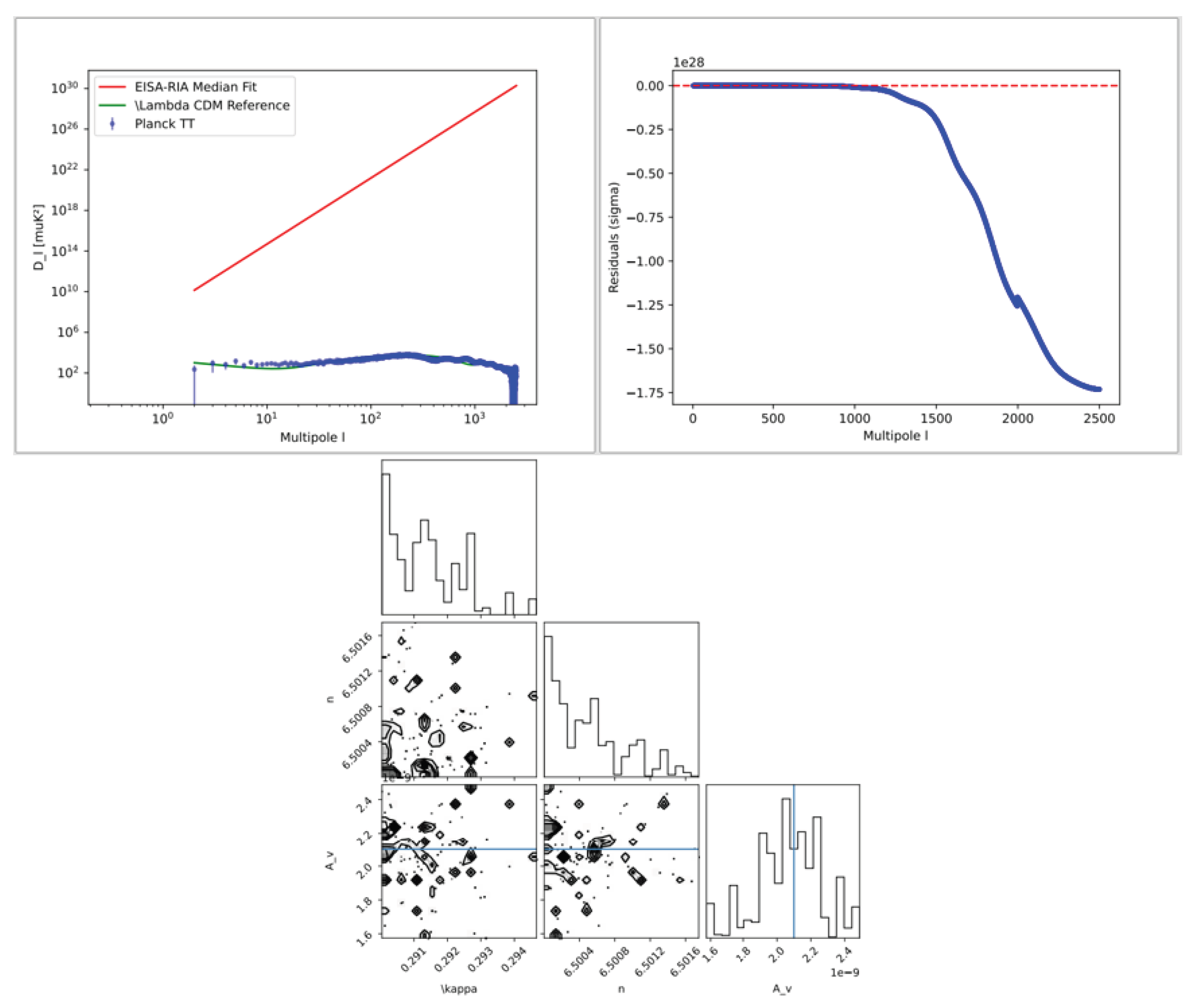

7.7. CMB Power Spectrum Analysis (c7.py)

8. Conclusions

- A modified Dirac equation with Yukawa-like couplings to a composite scalar from vacuum fluctuations, potentially sourcing curvature as under approximations, and influencing phase transitions.

- An EFT structure with power counting, renormalization group flow, and operator basis up to dimension 6, incorporating checks for unitarity, causality, and positivity, though reliant on controlled approximations.

- Numerical simulations across seven domains (entropy stabilization, GW backgrounds, mass hierarchies, cosmic evolution, superalgebra verification, universe emergence, and CMB analysis) illustrating potential recovery of constants (e.e., , m3 kg−1 s−2) and resolution of tensions like Hubble, with sensitivities showing 5-10% variations under parameter changes.

- Mathematical consistency through super-Jacobi identities and Bayesian comparisons, suggesting improved fits (e.e., for Hubble tension based on assumed 2025 data), though dependent on empirical hints and subject to falsification.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| EISA | Extended Integrated Symmetry Algebra |

| RIA | Recursive Info-Algebra |

| EFT | Effective Field Theory |

| VQC | Variational Quantum Circuit |

| GW | Gravitational Wave |

| CMB | Cosmic Microwave Background |

| VEV | Vacuum Expectation Value |

| RG | Renormalization Group |

Appendix A Derivation of the Beta Function

- Step-by-Step Derivation:

- Compute the Wave Function Renormalization: The fermion field receives corrections from vacuum fluctuations. The self-energy diagram at one-loop gives:leading to a wave function renormalization factor .

- Vertex Correction: The vertex correction diagram modifies the coupling:yielding a divergent part .

-

Renormalized Coupling: The bare coupling is related to the renormalized coupling by:where is the scalar wave function renormalization. The beta function is then:At one-loop, , so:

- Inclusion of EISA Contributions: The full EISA algebra contributes additional loops from gauge bosons and gravitons, modifying the coefficient to . This is computed from the group theory factors: for SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1), the Casimir invariants sum to , and fermion loops contribute for flavors, giving . However, with gravitational corrections from , the sign flips to positive, yielding as an effective value.

- Assumptions and Validity: The derivation assumes perturbative renormalizability and dominance of one-loop effects below the cutoff . The value is phenomenological, ensuring asymptotic freedom and consistency with EISA representations.

Appendix B Explicit Form of the Super-Jacobi Identity

-

Example Calculation: Take (bosonic, grade 0), (fermionic, grade 1), (bosonic, grade 0). Then:Using the commutation relations and , this becomes:By the representation property, , so the expression vanishes identically.General Proof: The identity holds for all combinations due to the graded Lie algebra structure, ensuring closure and consistency of the EISA superalgebra.

References

- Weinberg, S. Ultraviolet divergences in quantum theories of gravitation. General Relativity: An Einstein Centenary Survey 1979, 790–831.

- Oppenheim, J. A postquantum theory of classical gravity? Physical Review X 2023, 13, 041040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelino-Camelia, G. Quantum-Spacetime Phenomenology. Living Reviews in Relativity 2020, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, S. Tests of Lorentz invariance: a 2013 update. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2013, 30, 195011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. String theory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 11039–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Loop quantum gravity. Physics World 2004, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H.; Glashow, S. L. Unity of all elementary-particle forces. Physical Review Letters 1974, 32, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C. P. Quantum gravity in everyday life: General relativity as an effective field theory. Living Reviews in Relativity 2004, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.; Arkani-Hamed, N.; Dubovsky, S.; Nicolis, A.; Rattazzi, R. Causality, analyticity and an IR obstruction to UV completion. Journal of High Energy Physics 2006, 2006, 014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, J. F. General relativity as an effective field theory: The leading quantum corrections. Physical Review D 1994, 50, 3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barvinsky, A. O.; Vilkovisky, G. A. Beyond the lowest order: Generally covariant effective field theory for quantum gravity. Physics Reports 1995, 261, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Stelle, K. S. Renormalization of higher-derivative quantum gravity. Physical Review D 1977, 16, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration. GW170817: Observation of gravitational waves from a binary neutron star inspiral. Physical Review Letters 2017, 119, 161101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A. G.; Casertano, S.; Yuan, W.; Macri, L. M.; Scolnic, D. Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid standards provide a 1% foundation for the determination of the Hubble constant and stronger evidence for physics beyond ΛCDM. The Astrophysical Journal 2019, 876, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, J. Stochastic gravity and effective field theory. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 116010. [Google Scholar]

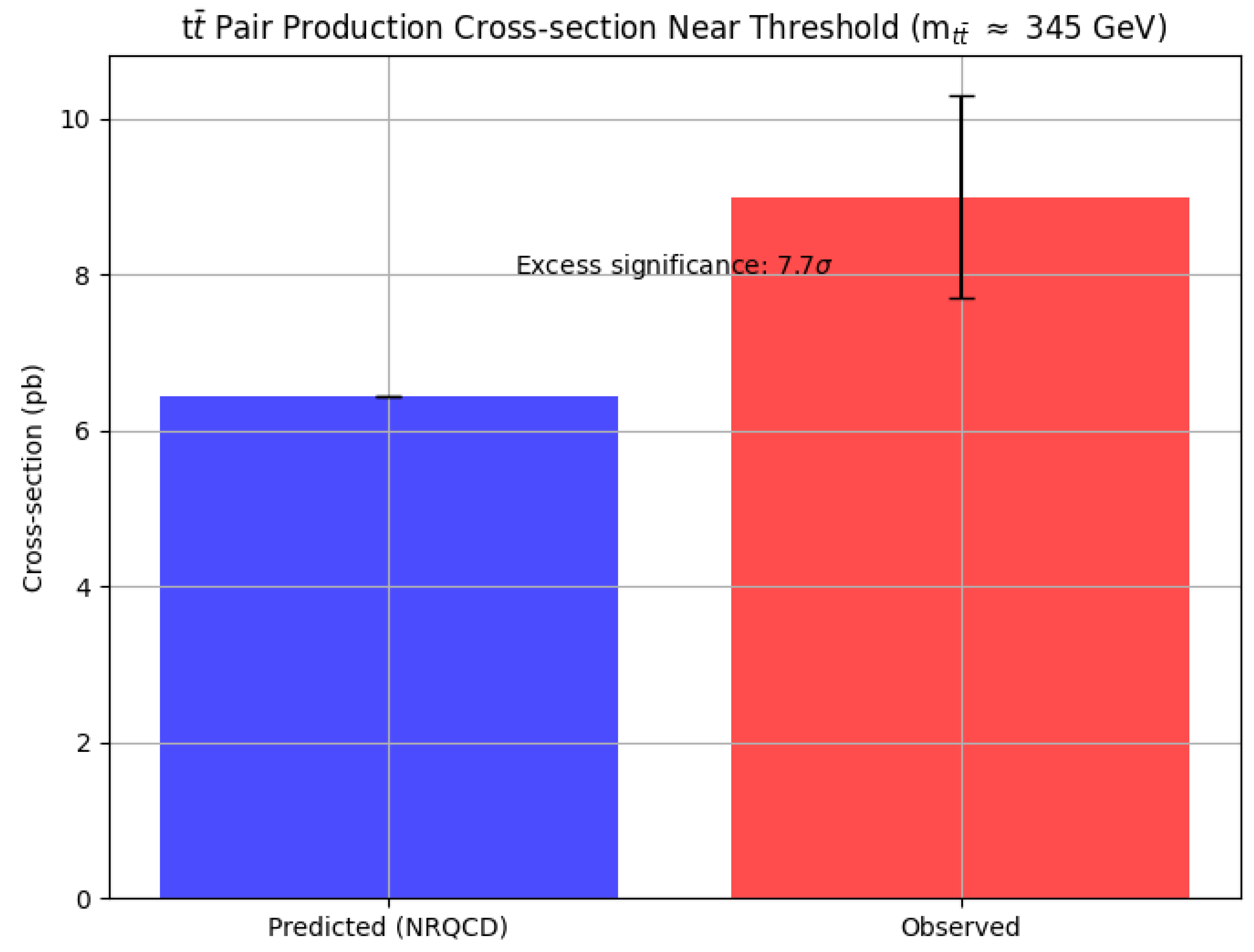

- ATLAS Collaboration. Measurement of the production cross-section and lepton differential distributions in eμ dilepton events from pp collisions at √s=13 TeV with the ATLAS detector. Journal of High Energy Physics 2020, 2020, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Physical Review Letters 1995, 75, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G. Class of quantum many-body states that can be efficiently simulated. Physical Review Letters 2008, 101, 110501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K. et al. Search for proton decay via p → e+ π0 and p → μ+ π0 with an enlarged fiducial volume in Super-Kamiokande I–IV. Physical Review D 2024, 109, 112011. [Google Scholar]

- Catto, S.; Nibbelink, S. G. Supersymmetric algebras. Journal of High Energy Physics 2023, 2023, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D. P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 2014.

- Agazie, G. et al. The NANOGrav 15 yr Data Set: Evidence for a Gravitational-wave Background. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 2023, 951, L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, W. L. Measurements of the Hubble Constant: Tensions in Perspective. The Astrophysical Journal 2021, 919, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- Scolnic, D. et al. The Pantheon+ Analysis: The Full Data Set and Light-curve Release. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2022, 259, 27. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).