Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Preparation of Palm Kernel Shells

2.2. Determination of Chemical Composition of Palm Kernel Shell

2.3. Pretreatment of Raw Palm Kernel Shells

2.4. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Pretreated Palm Kernel Shell Residue

2.4.1. Determination of Glucose Concentration in Hydrolysate

2.5. Fermentation of Hydrolysate

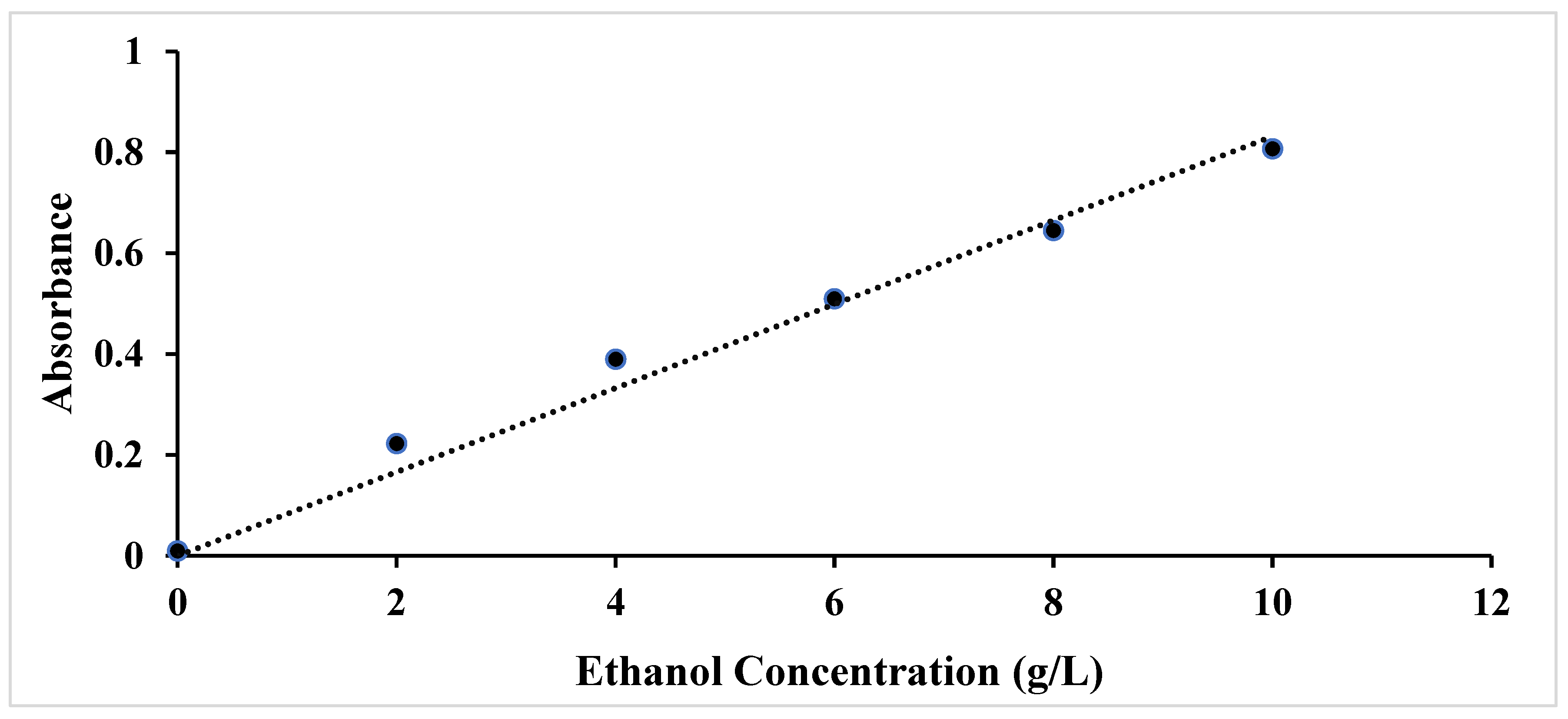

2.5.1. Determination of Bioethanol in Fermented Mixture

2.5.2. Experimental Design for Fermentation Experiment

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Composition of Palm Kernel Shells

3.2. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Acid Pretreated Palm Kernel Shells

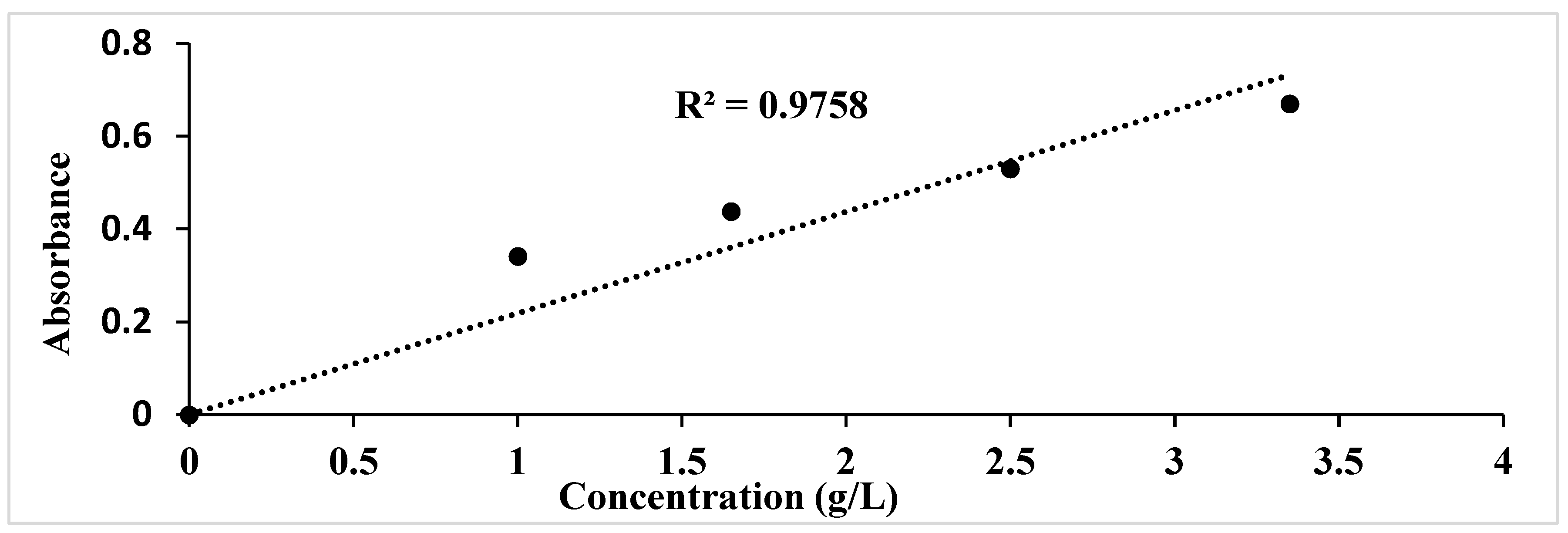

3.2.1. Determination of Glucose Concentration in Enzymatic Hydrolysates

3.3. Fermentation of Cellulosic Hydrolysates

3.3.1. Determination of Bioethanol in Fermented Samples

3.3.2. Experimental design for fermentation conditions

3.3.3. Statistical Analysis of Fermentation Conditions

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | |

| Model | 53.96 | 9 | 6.00 | 5.79 | 0.0141 | Significant |

| A-Yeast concentration | 12.18 | 1 | 12.18 | 11.76 | 0.0186 | |

| B-Temp. | 4.59 | 1 | 4.59 | 4.44 | 0.0890 | |

| C-Reaction time | 1.18 | 1 | 1.18 | 1.14 | 0.3338 | |

| AB | 3.21 | 1 | 3.21 | 3.10 | 0.1384 | |

| AC | 0.2082 | 1 | 0.2082 | 0.2012 | 0.6725 | |

| BC | 26.52 | 1 | 26.52 | 25.62 | 0.0039 | |

| A2 | 0.7525 | 1 | 0.7525 | 0.7270 | 0.4328 | |

| B2 | 0.5053 | 1 | 0.5053 | 0.4882 | 0.5159 | |

| C2 | 4.60 | 1 | 4.60 | 4.45 | 0.0888 | |

| Residual | 5.18 | 5 | 1.04 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 3.05 | 3 | 1.02 | 0.9586 | 0.5470 | Not significant |

| Pure Error | 2.12 | 2 | 1.06 | |||

| Cor Total | 59.14 | 14 |

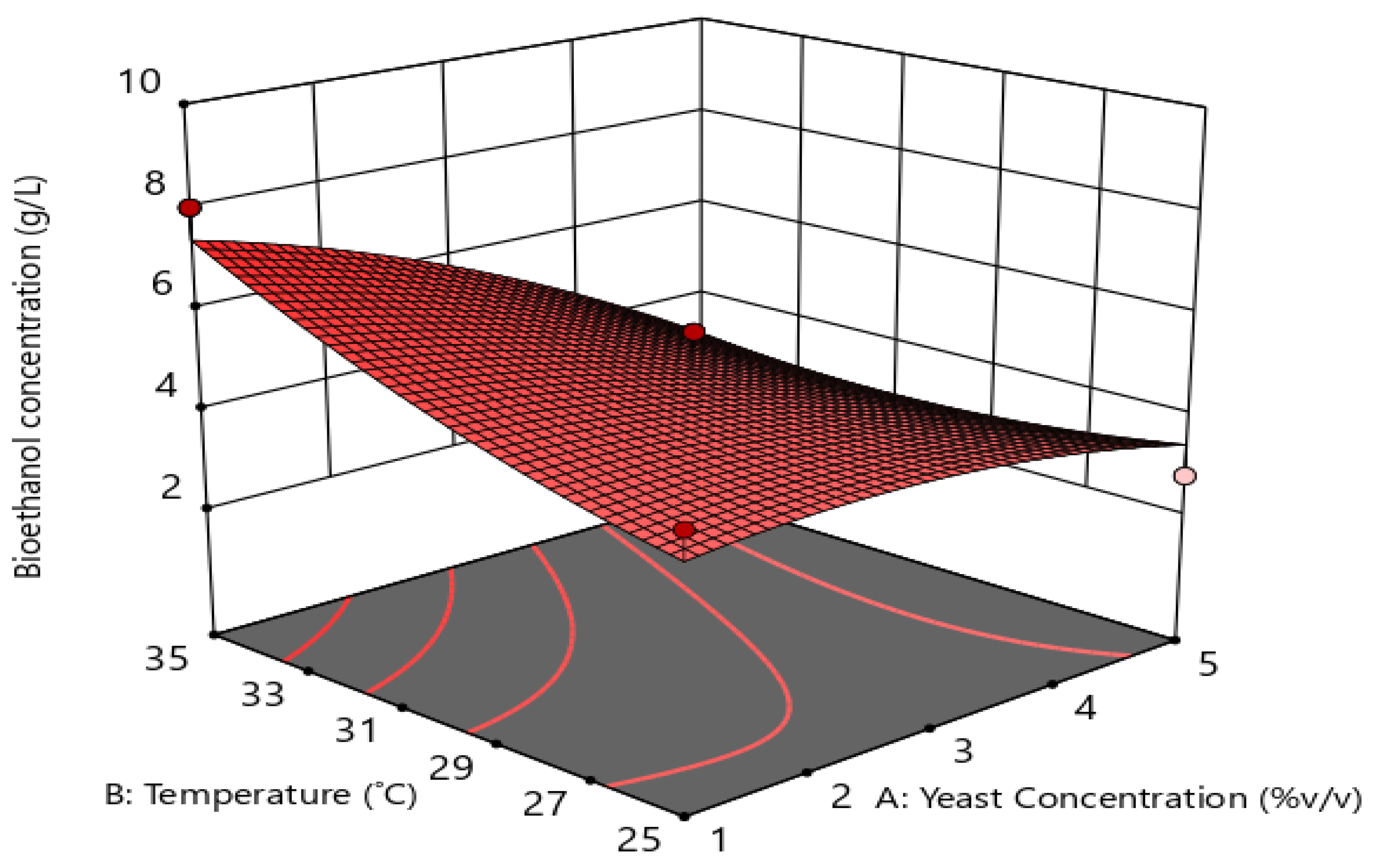

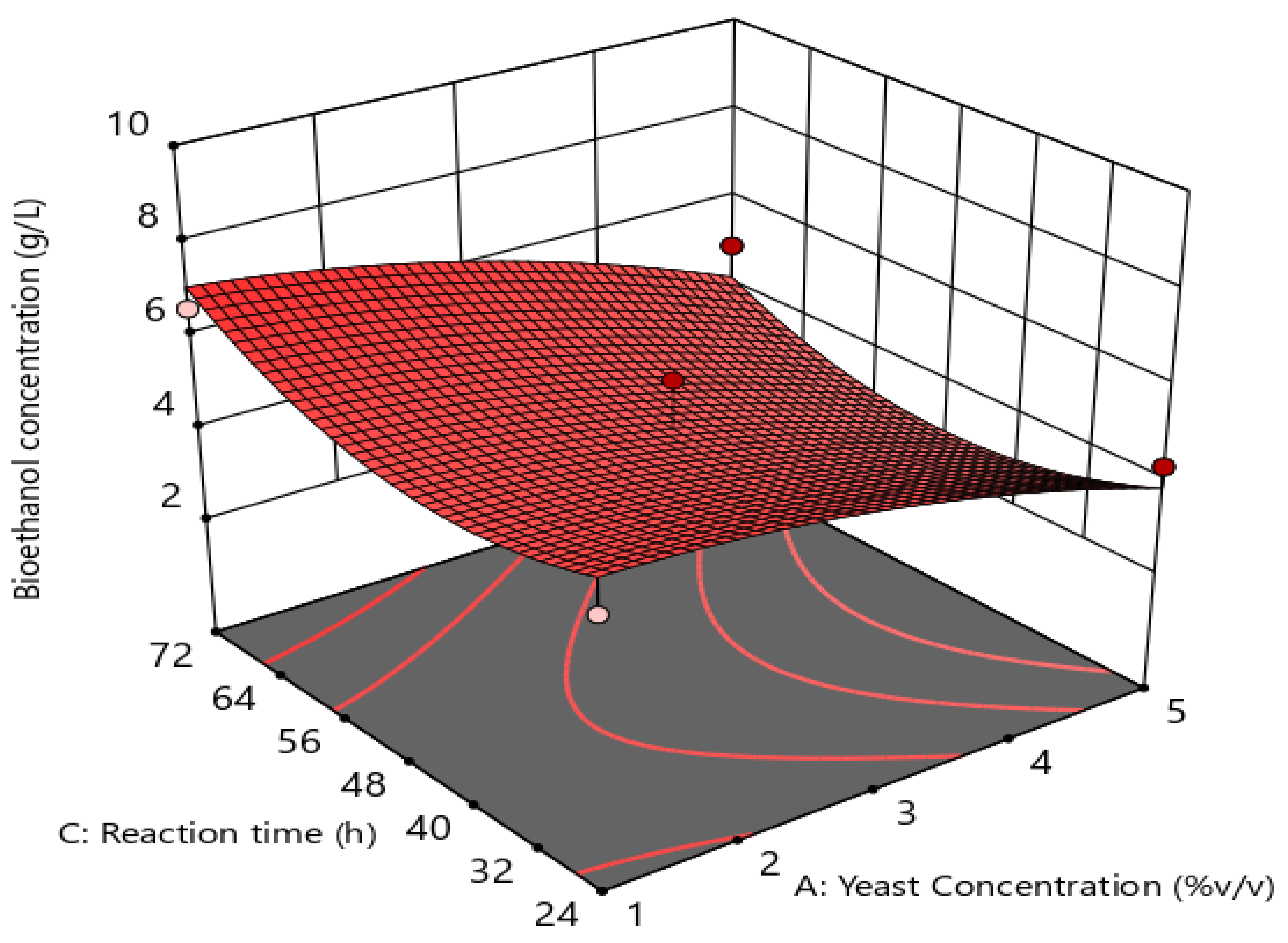

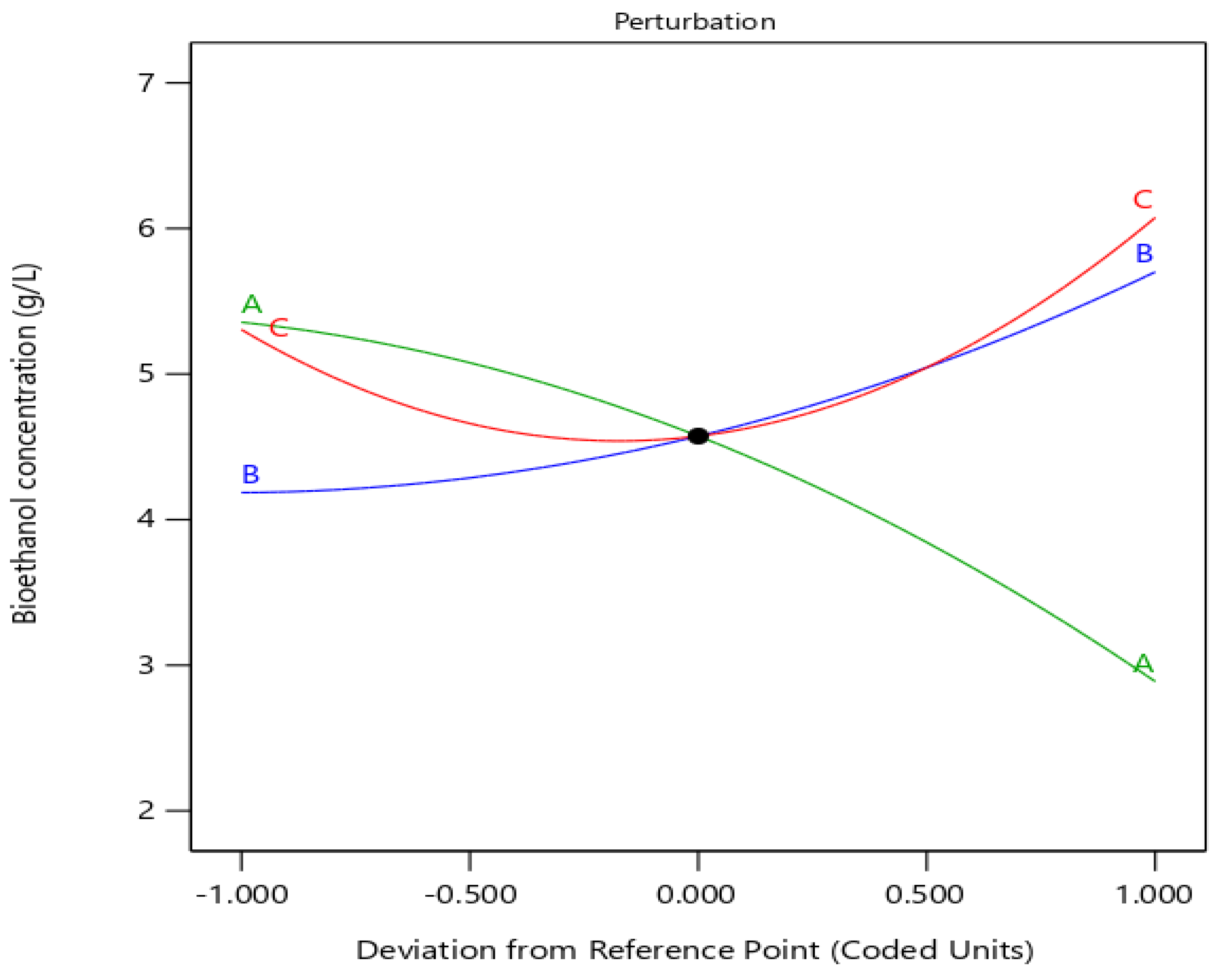

3.3.4. Interactive Effects of Process Variables

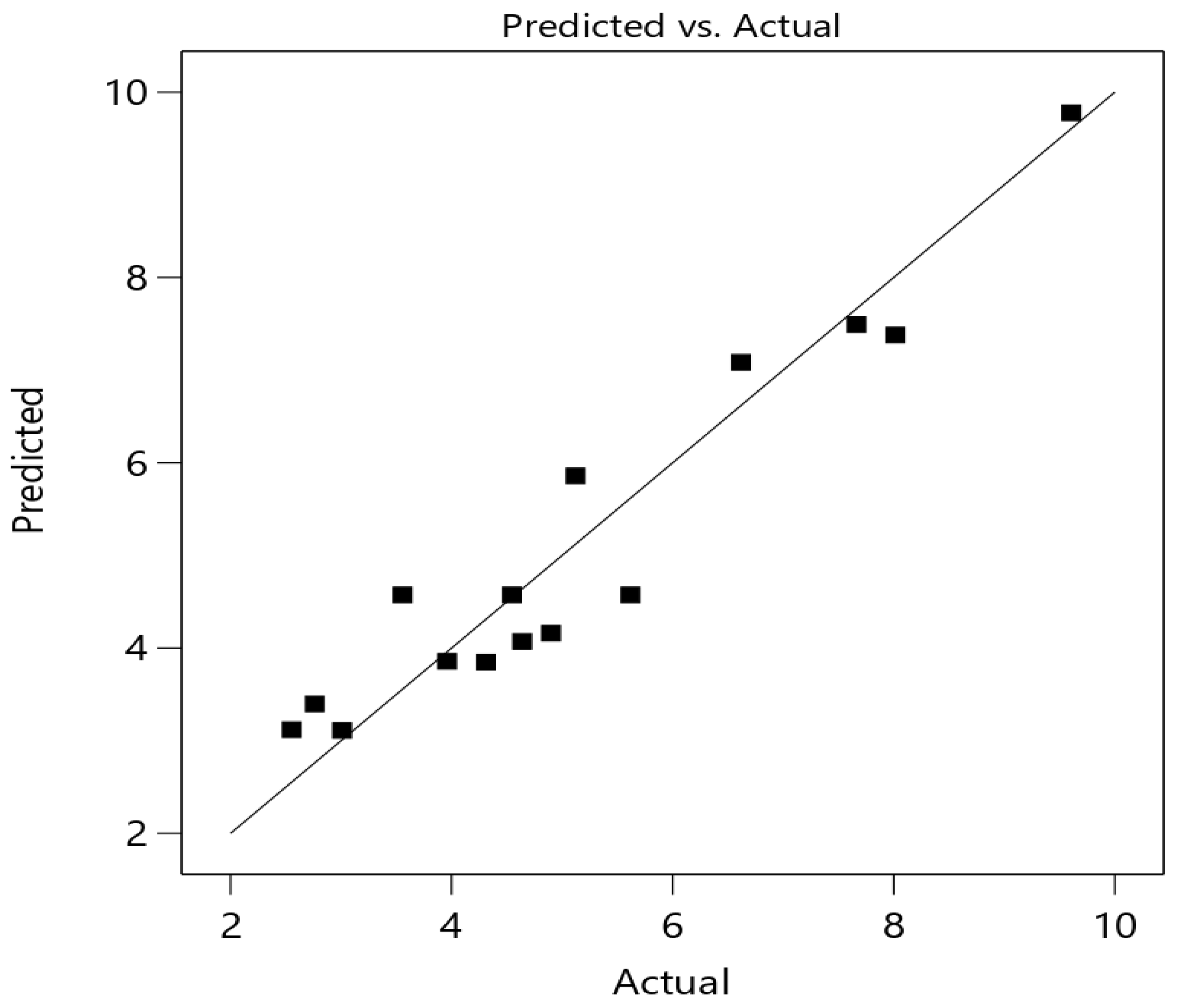

3.3.5. Validation of the Developed Model for Optimal Fermentation Conditions

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

Use of AI Tools Declaration

References

- Sanni, S.E.; Oni, B.A.; Okoro, E.E. Heterogeneous Catalytic Gasification of Biomass to Biofuels and Bioproducts: A Review. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 965–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ren, J.; Li, H.; Deng, A.; Sun, R. Direct transformation of xylan-type hemicelluloses to furfural via SnCl4 catalysts in aqueous and biphasic systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 183, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rapoport, A.; Kunze, G.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, B. Multifarious pretreatment strategies for the lignocellulosic substrates for the generation of renewable and sustainable biofuels: A review. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 1228–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.B.T.L.; Wu, T.Y. A review on solvent systems for furfural production from lignocellulosic biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.K.; Sulaiman, S.A.; Yusup, S.; Dol, S.S.; Inayat, M.; Umar, H.A. Exploring the potential of coconut shell biomass for charcoal production. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adejumo, I.O.; Adebiyi, O.A. Agricultural solid wastes: causes, effects, and effective management. Strategies of sustainable solid waste management 2020, 8, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Akhlisah, Z.; Yunus, R.; Abidin, Z.; Lim, B.; Kania, D. Pretreatment methods for an effective conversion of oil palm biomass into sugars and high-value chemicals. Biomass- Bioenergy 2021, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Buang, A.; Bhat, A. Renewable and sustainable bioenergy production from microalgal co-cultivation with palm oil mill effluent (POME): A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchegbulam, I.; Momoh, E.O.; Agan, S.A. Potentials of palm kernel shell derivatives: a critical review on waste recovery for environmental sustainability. Clean. Mater. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffour-Awuah, E.; Akinlabi, S.A.; Jen, T.C.; Hassan, S.; Okokpujie, I.P.; Ishola, F. Characteristics of Palm Kernel Shell and Palm Kernel Shell-Polymer Composites: A Review.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012090.

- Sanjuan-Acosta, M.J.; Tobón-Manjarres, K.; Sánchez-Tuirán, E.; Ojeda-Delgado, K.A.; González-Delgado, Á.D. An Optimization Approach Based on Superstructures for Bioethanol Production from African Palm Kernel Shells. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 30, 2293–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efeovbokhan, V.E.; Egwari, L.; Alagbe, E.E.; Adeyemi, J.T.; Taiwo, O.S. Production of bioethanol from hybrid cassava pulp and peel using microbial and acid hydrolysis. BioResources 2019, 14, 2596–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Bhardwaj, N.; Agrawal, K.; Chaturvedi, V.; Verma, P. Current perspective on pretreatment technologies using lignocellulosic biomass: An emerging biorefinery concept. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabed, H.; Sahu, J.; Boyce, A.; Faruq, G. Fuel ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass: An overview on feedstocks and technological approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 751–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhang, S.; Choojit, S.; Reungpeerakul, T.; Sangwichien, C. Bioethanol production from oil palm empty fruit bunch with SSF and SHF processes using Kluyveromyces marxianus yeast. Cellulose 2019, 27, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, F.; Cheng, C.-L.; Lo, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chang, J.-S.; Leu, S.-Y.; Lee, D.-J. Continuous cellulosic bioethanol co-fermentation by immobilized Zymomonas mobilis and suspended Pichia stipitis in a two-stage process. Appl. Energy 2020, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamae, S.; Dechatiwongse, P.; Choorit, W.; Chisti, Y.; Prasertsan, P. Cellulose and hemicellulose recovery from oil palm empty fruit bunch (EFB) fibers and production of sugars from the fibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 155, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, S.H.M.; Abdulla, R.; Jambo, S.A.; Marbawi, H.; Gansau, J.A.; Faik, A.A.M.; Rodrigues, K.F. Yeasts in sustainable bioethanol production: A review. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2017, 10, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, A.; Zhang, B. (2010). Dilute and concentrated acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioalcohol Production 143 – 158. https://doi.org/10.1533/9781845699611.2.143(2010). Dilute and concentrated acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioalcohol Production. [CrossRef]

- Agustini, N.W.S.; Hidhayati, N.; A Wibisono, S. Effect of hydrolysis time and acid concentration on bioethanol production of microalga Scenedesmus sp..CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012029.

- Madadi M, Tu Y, Abbas A (2017). Recent status on enzymatic saccharification of lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production. Electron J Biol 13: 135 – 143. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aqleem-Abbas-2/publication/316315642_Recent_Status_on_Enzymatic_Saccharification_of_Lignocellulosic_Biomass_for_Bioethanol_Production/links/5d54f51345851530407572ed/Recent-Status-on-Enzymatic-Saccharification-of-Lignocellulosic-Biomass-for-Bioethanol-Production.

- Khawla, B.J.; Sameh, M.; Imen, G.; Donyes, F.; Dhouha, G.; Raoudha, E.G.; Oumèma, N.-E. Potato peel as feedstock for bioethanol production: A comparison of acidic and enzymatic hydrolysis. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 52, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, K.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Bioethanol Production by Enzymatic Hydrolysis from Different Lignocellulosic Sources. Molecules 2021, 26, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, J.K.; Gnansounou, E. Furfural production from empty fruit bunch – A biorefinery approach. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 69, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demi̇rBaş, A. Bioethanol from Cellulosic Materials: A Renewable Motor Fuel from Biomass. Energy Sources 2005, 27, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Taher, I.; Fickers, P.; Chniti, S.; Hassouna, M. Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation conditions for improved bioethanol production from potato peel residues. Biotechnol. Prog. 2017, 33, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabrina, M.S.S.; Roshanida, A.R.; Norzita, N. Pretreatment of Oil Palm Fronds for Improving Hemicelluloses Content for Higher Recovery of Xylose. J. Teknol. 2013, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Chairul; Rita, N. ; Wulandari, R.; Sari, V.A. Hydrolysis process of oil palm empty fruit bunches for bioethanol production with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 87, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iberahim, N.I.; Jahim, J.M.; Harun, S.; Nor, M.T.M.; Hassan, O. Sodium Hydroxide Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Oil Palm Mesocarp Fiber. Int. J. Chem. Eng. Appl. 2013, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthikitpanya, S.; Reungsang, A.; Prasertsan, P. Two-stage thermophilic bio-hydrogen and methane production from lime-pretreated oil palm trunk by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 4284–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adney B, Baker J (2008). Measurement of Cellulase Activities. Laboratory analytical procedure, 1 – 11.

- Ayeni, A.O.; Omoleye, J.A.; Hymore, F.K.; Pandey, R.A. EFFECTIVE ALKALINE PEROXIDE OXIDATION PRETREATMENT OF SHEA TREE SAWDUST FOR THE PRODUCTION OF BIOFUELS: KINETICS OF DELIGNIFICATION AND ENZYMATIC CONVERSION TO SUGAR AND SUBSEQUENT PRODUCTION OF ETHANOL BY FERMENTATION USING Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triwahyuni, E.; Hariyanti, S.; Dahnum, D.; Nurdin, M.; Abimanyu, H. Optimization of Saccharification and Fermentation Process in Bioethanol Production from Oil Palm Fronds. Procedia Chem. 2015, 16, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, C.H. Bioethanol production using the sequential acid/alkali-pretreated empty palm fruit bunch fiber. Renew. Energy 2013, 54, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahnum, D.; Tasum, S.O.; Triwahyuni, E.; Nurdin, M.; Abimanyu, H. Comparison of SHF and SSF Processes Using Enzyme and Dry Yeast for Optimization of Bioethanol Production from Empty Fruit Bunch. Energy Procedia 2015, 68, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, N.A.; Aruwajoye, G.; Sewsynker-Sukai, Y.; Kana, E.G. Valorisation of potato peel wastes for bioethanol production using simultaneous saccharification and fermentation: Process optimization and kinetic assessment. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim JK, Oh BR., Shin H.J, et al. (2008). Statistical optimization of enzymatic saccharification and ethanol fermentation using food waste. Process Biochem 43 (11): 1308-1312. http://www.sciencedirect. 1359.

| Symbol | Independent variable | Unit | Code | ||

| -1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| A | Yeast concentration | % v/v | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| B | Temperature | ˚C | 25 | 30 | 35 |

| C | Reaction time | h | 24 | 48 | 72 |

| Raw PKS (% w/w) | Pretreated PKS (% w/w) | ||

| Component | Acid | Alkaline | |

| Hemicellulose | 41.73 ± 1.07 | 15.18 ± 0.76 | 11.23 ± 0.6 |

| Cellulose | 31.06 ± 0.92 | 22.71 ± 0.31 | 45.62 ± 0.2 |

| Lignin | 27.5 ± 0.8 | 23.12 ± 0.56 | 12.40 ± 0.5 |

| Ash | 1.53 ± 0.26 | 1.21 ± 0.03 | |

| Extractives | 0.5 ± 0.12 | 0.04 | |

| Enzyme concentration (FPU/g biomass) | Glucose (g/L) |

| 10 | 32.19 ± 0.0 |

| 20 | 36.37 ± 0.4 |

| 30 | 39.78 ± 0.2 |

| Run | Yeast concentration (% v/v) | Temperature (˚C) | Reaction time (h) | Bioethanol concentration (g/L) |

| 1 | 1 | 25 | 48 | 4.639 ± 0.0 |

| 2 | 1 | 35 | 48 | 8.016 ± 0.0 |

| 3 | 1 | 30 | 24 | 5.121 ± 0.0 |

| 4 | 3 | 30 | 48 | 4.548 ± 0.0 |

| 5 | 3 | 35 | 72 | 9.606 ± 0.0 |

| 6 | 3 | 30 | 48 | 5.617 ± 0.0 |

| 7 | 5 | 30 | 72 | 4.900 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 5 | 35 | 48 | 2.553 ± 0.3 |

| 9 | 3 | 35 | 24 | 3.961 ± 0.1 |

| 10 | 3 | 25 | 72 | 3.009 ± 0.0 |

| 11 | 1 | 30 | 72 | 6.621 ± 0.0 |

| 12 | 3 | 30 | 48 | 3.557 ± 0.0 |

| 13 | 3 | 25 | 24 | 7.664 ± 0.2 |

| 14 | 5 | 30 | 24 | 4.313 ± 0.4 |

| 15 | 5 | 25 | 48 | 2.761 ± 0.0 |

| Optimum condition |

Bioethanol concentration (g/L) |

|||

| Yeast concentration (% v/v) | Temperature (˚C) | Reaction time (hrs) | Predicted values | Experimental values |

|

1.506 |

34.90 | 69.61 | 10.22 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).