Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The -Model: A Phase-Ontological Framework

2.1. The Primordial Substrate: The Universal Phase Field

- Phase : encodes relations and structure. Its gradients seed emergent geometry and dynamics.

- Amplitude : represents the density of distinction, i.e. the capacity of a region to sustain coherent, distinguishable structure.

2.2. The Criterion of Distinguishability: The -Postulate

2.3. Emergent Geometry and Matter

2.4. Examples of Emergent Structures

2.5. Illustrative Example: Harmonic Oscillator Quantization

2.6. Outlook: Spin and Spinc Structures

3. The Topological Origin of Quantization Rules

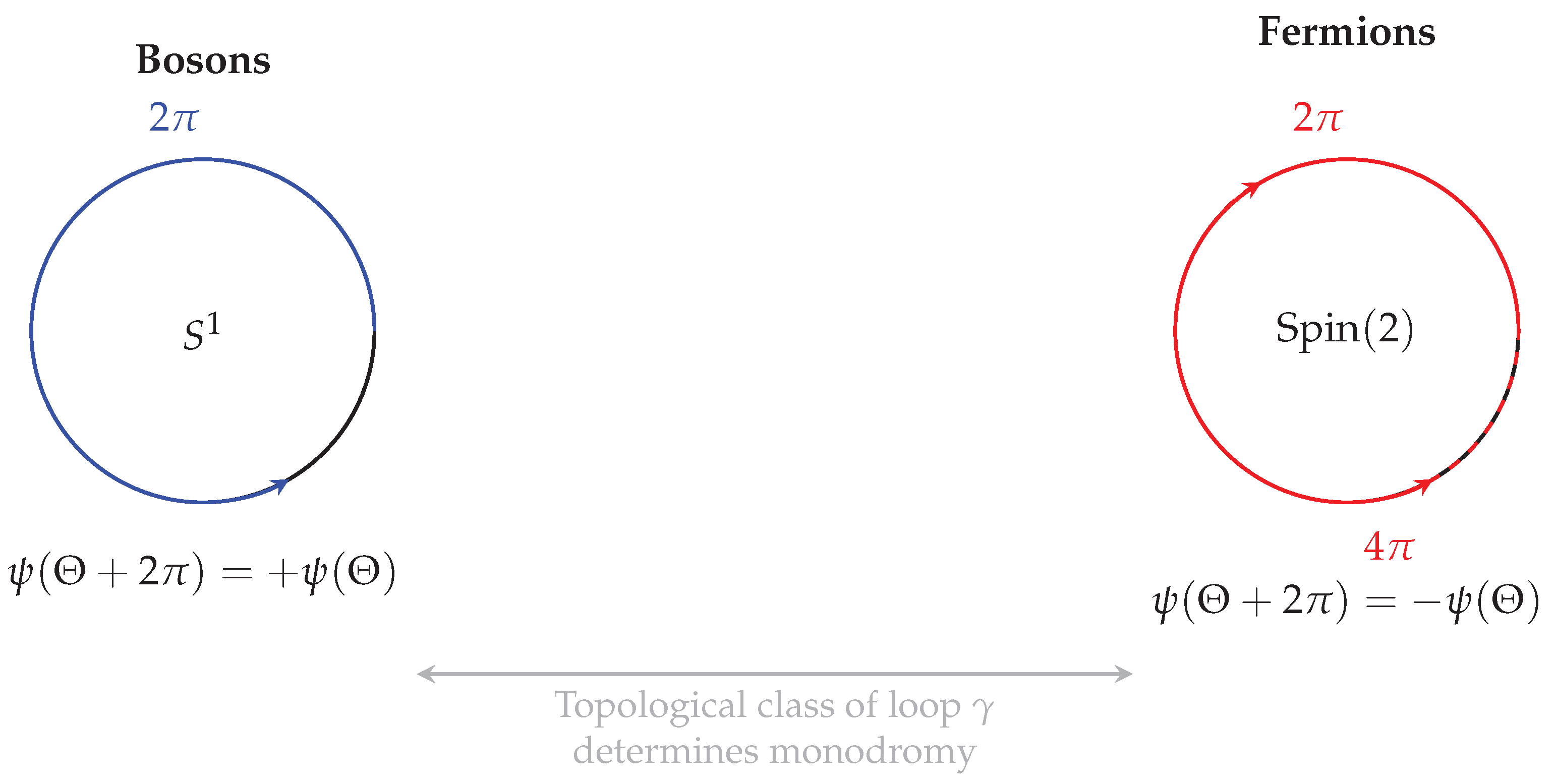

3.1. Monodromy as a Homomorphism

3.2. Two Fundamental Scenarios of Monodromy

3.2.1. Scenario 1: Trivial Monodromy (Bosons)

3.2.2. Scenario 2: Nontrivial Monodromy (Fermions)

3.3. Theorem: Quantization from Monodromy

3.4. Connection to Phase-Space Cells

3.5. Generalizations: Anyons and Beyond

4. Rigorous Derivation via Geometric Quantization

4.1. Step 1: Constructing the Geometric Bundles

The Prequantum Line Bundle :

The Spinc Bundle :

4.2. Step 2: Defining the Physical State

4.3. Step 3: Consistency Condition

4.4. Step 4: Holonomies of the Component Bundles

Lemma 1 (Prequantum Holonomy).

Lemma 2 (Spinc Holonomy).

4.5. Step 5: Synthesis and Quantization Rules

Theorem (Quantization Rule from Bundle Consistency).

5. Discussion: The Status of ℏ and Emergent Spin

5.1. The Status of ℏ as a Structural Invariant

5.2. Spin as a Topological Phenomenon

6. Consistency with Physical Phenomena

6.1. Qualitative Support from Foundational Experiments

Aharonov–Bohm Effect:

Neutron Interferometry:

dc-SQUID Flux Quantization:

Quantum Hall Effect:

Quantum Decoherence:

6.2. Illustrative Consistency Check: The CMS Dimuon Anomaly (As Future Directions)

Summary

7. Limitations and Future Directions

Near-Term Limitations

Constants

Gravity

Manifold Assumptions

Programmatic Outlook

Mass Spectrum of Particles

Emergent Gravity

Dark Energy and Topological Defects

Exotic Statistics and Fractonic Phases

From -I to -II

8. Conclusion

References

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1930; Classic monograph; first edition 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Dirac, P.A.M. The Principles of Quantum Mechanics, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Kostant, B. Quantization and Unitary Representations. In Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1970; Vol. 170, pp. 87–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souriau, J.M. Structure des Systèmes Dynamiques; Dunod: Paris, 1970. English translation: Structure of Dynamical Systems, Birkhäuser, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse, N.M.J. Geometric Quantization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal Phase Factors Accompanying Adiabatic Changes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1984, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B. Holonomy, the quantum adiabatic theorem, and Berry’s phase. Physical Review Letters 1983, 51, 2167–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, A.; Mostafazadeh, A.; Koizumi, H.; Niu, Q.; Zwanziger, J. The Geometric Phase in Quantum Systems; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, V.I. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, second ed.; Vol. 60, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag: New York, 1989; Translated from the Russian by K. Vogtmann and A. Weinstein. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR 1967, 177, 70–71, English translation in: Sov. Phys. Dokl. 12, 1040-1041 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- Skyrme, T.H.R. A unified field theory of mesons and baryons. Nuclear Physics 1962, 31, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Magnetic monopoles in unified gauge theories. Nuclear Physics B 1974, 79, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addazi, A.; et al. Emergent Gravity from Topological Quantum Field Theory: Stochastic Gradient Flow Perspective away from the Quantum Gravity Problem. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pillado, J.J.; et al. Effective Actions for Domain Wall Dynamics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2411.13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G. The renormalization group: Critical phenomena and the Kondo problem. Reviews of Modern Physics 1975, 47, 773–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polchinski, J. Renormalization and Effective Lagrangians. Nuclear Physics B 1984, 231, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. Magnetic flux, angular momentum, and statistics. Physical Review Letters 1982, 48, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fractional Statistics and Anyon Superconductivity; World Scientific, 1990. Wilczek, F. (Ed.). [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Annals of Physics 2003, 303, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiyah, M.F. K-Theory, 2nd ed.; Westview Press, 1989. Reprint of the 1967 Addison-Wesley edition.

- Kirillov, A.A. Lectures on the Orbit Method; Vol. 64, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Freed, D.S.; Uhlenbeck, K.K. Instantons and Four-Manifolds; Vol. 1, Mathematical Sciences Research Institute Publications, Springer-Verlag: New York, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, D.S.; Moore, G.W. Twisted Equivariant Matter. Annales Henri Poincaré 2013, 14, 1927–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, H.; Zeilinger, A.; Badurek, G.; Wilfing, A.; Bauspiess, W.; Bonse, U. Verification of coherent spinor rotation of fermions. Physics Letters A 1975, 54, 425–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonov, Y.; Bohm, D. Significance of Electromagnetic Potentials in the Quantum Theory. Physical Review 1959, 115, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonomura, A.; Osakabe, N.; Matsuda, T.; Kawasaki, T.; Endo, J. Evidence for Aharonov-Bohm Effect with Magnetic Field Completely Shielded from Electron Wave. Physical Review Letters 1986, 56, 792–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, M.; Weder, R. The Aharonov–Bohm Effect and Tonomura et al. Experiments: Rigorous Results. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2009, 50, 122108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.A.; Washburn, S.; Umbach, C.P.; Laibowitz, R.B. Observation of h/e Aharonov–Bohm Oscillations in Normal-Metal Rings. Physical Review Letters 1985, 54, 2696–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colella, R.; Overhauser, A.W.; Werner, S.A. Observation of Gravitationally Induced Quantum Interference. Physical Review Letters 1975, 34, 1472–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likharev, K.K. Single-electron devices and their applications. Proceedings of the IEEE 1999, 87, 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Sheng, P.; Davidović, D. Observation of Large h/2e and h/4e Oscillations in a Proximity dc Superconducting Quantum Interference Device. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0803.3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, M.; Nakamura, K.; Kawamura, M.; Hisamatsu, H.; Asano, H. Higher Harmonic Resistance Oscillations in Microbridge Superconducting Nb Ring. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Klitzing, K.; Dorda, G.; Pepper, M. New Method for High-Accuracy Determination of the Fine-Structure Constant Based on Quantized Hall Resistance. Physical Review Letters 1980, 45, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouless, D.J.; Kohmoto, M.; Nightingale, M.P.; den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall Conductance in a Two-Dimensional Periodic Potential. Physical Review Letters 1982, 49, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, D.C.; Störmer, H.L.; Gossard, A.C. Two-Dimensional Magnetotransport in the Extreme Quantum Limit. Physical Review Letters 1982, 48, 1559–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosshauer, M. Decoherence and the Quantum-to-Classical Transition; Springer, 2007. [CrossRef]

- CMS Collaboration. Search for heavy neutral leptons in multilepton final states in proton-proton collisions at s=13 TeV. https://www.hepdata.net/record/ins2763679?version=1, 2024. HEPData record INS2763679 (v1).

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Physical Review Letters 1995, 75, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New Insights. Reports on Progress in Physics 2010, 73, 046901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.R.; Sur, S. Quantum Induced Gravity. Physical Review D 2021, 104, 066015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, Y.; Paul, N.; Fu, L. Emergent gravity and gravitational lensing in quantum materials. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.04335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Blanco-Pillado, J.J.; Garriga, J.; Vilenkin, A. Topological Defects from the Multiverse. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2015, 2015, 059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretko, M. Subdimensional particle structure of higher rank U(1) spin liquids. Physical Review B 2017, 95, 115139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The general setting is a bundle, of which the spin bundle in Section 4 is a representative case. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).