1. Introduction

Planck’s constant ℏ is one of the cornerstones of modern physics. In conventional quantum mechanics, however, it is not derived but introduced axiomatically: as the scale in the canonical commutator , or in the energy–frequency relation . These relations, while operationally fundamental, do not by themselves explain why such a constant should exist, nor why its value is universal across all systems. This long-standing situation leaves a foundational gap at the basis of quantization.

In this work we address this problem by presenting a derivation of

ℏ as a structural invariant from first principles. The framework combines methods of geometric quantization [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] with effective field theory and renormalization group analysis [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. On the one hand, the integrality of the first Chern class of the prequantum

bundle enforces a topological normalization:

ℏ arises as the minimal symplectic flux through a primitive cycle. On the other hand, integrating out heavy modes induces low-energy couplings that exhibit a renormalization–group stationary point (the “support cell”), where the topological and dynamical definitions of

ℏ coincide. This **dual characterization establishes** Planck’s constant as a structural invariant of phase topology and effective field theory, rather than a postulated parameter.

The key message is that quantization appears not as an axiom but as an emergent consequence of topology and renormalization within this framework. Planck’s constant thus functions as a universal invariant threshold for coherent quantum phenomena, addressing the foundational incompleteness of standard formulations. This perspective provides a structural **closure that unifies** geometric quantization with field-theoretic renormalization, and reframes ℏ as an emergent universal constant.

The structure of the article is as follows. Sec. 2 presents the detailed derivation of ℏ, combining topological normalization and RG–stationarity to obtain the structural relation . Sec. 3 discusses experimental consistency, showing how established quantum effects—such as the Aharonov–Bohm phase, Josephson relations, flux quantization, the quantum Hall effect, and quantum speed limits—confirm the derived threshold. Sec. 4 explains calibration to SI units, identifying the single experimental anchor required. Sec. 5 concludes with implications for the foundations of quantization. Finally, Sec. 6 outlines future perspectives, including the possible extension of this approach to other fundamental constants and its relation to entropy bounds and holographic principles.

2. Derivation of ℏ as a Structural Invariant

We now present a derivation of Planck’s constant

ℏ as a structural invariant, avoiding its introduction as an independent postulate. The argument proceeds in three layers: (i) topological normalization from geometric quantization, (ii) induced low–energy constants from the heat–kernel expansion, and (iii) renormalization–group (RG) stationarity at the effective support cell. The outcome is the relation

in model units, identifying

ℏ as both a topological and a dynamical invariant. Conversion to SI units requires a single metrological anchor (Sec.

Section 2.4).

2.1. Topological Normalization

2.1.1. Prequantum Bundle

Let

be a symplectic phase space with

. Introduce a dimensionful action scale

S via the prequantum connection

By Chern–Weil theory the first Chern class satisfies

2.1.2. Symplectic Flux

For any closed 2–cycle

,

For a primitive generator

with

,

fixes an absolute symplectic flux per primitive cycle.

Dimensional check. The angle is dimensionless while carries units of action, so has units of action. Hence S has units of action, as required.

2.1.3. Integrality Condition and Physical Meaning

Locally

, so that

For a primitive cycle with

, this reduces to the Bohr–Sommerfeld rule. The Maslov index ensures stability of interference phases, so (

3) captures the minimal action required for sustainable, distinguishable phase configurations [

6,

7,

13]. In what follows we will identify

S with

ℏ at the RG–stationary point.

2.2. Induced Constants from the Heat–Kernel Expansion

2.2.1. Heat–Kernel Expansion

Consider

minimally coupled to

. Split

, with

a heavy mode of mass

. Integrating out

at one loop yields the effective action for

, with Seeley–DeWitt expansion [

8,

9,

10,

11]:

2.2.2. Explicit Induced Couplings

In 4D, and for a single scalar mode in the

scheme with

, the induced constants take the form [

12,

14]:

Different field contents or renormalization schemes change only the numerical coefficients; the qualitative structure is robust. Physically, these terms reflect coarse–graining: high–frequency fluctuations of

renormalize the low–energy stiffness, gauge and gravitational couplings. Numbers shown correspond to a single real scalar in

with

; other field contents and schemes shift the prefactors (including the Sakharov–type gravitational coefficient) but do not affect the existence of a finite stationary reconciliation.

2.3. RG–Stationary Support Cell

2.3.1. Two Dynamical Expressions for the Action Scale S

The topological scale

S defined in (

3) must be consistent with the dynamical parameters of the low-energy effective theory. This requirement yields two independent expressions for

S.

(i)

From the gauge sector. The prequantum covariant derivative is defined as

We normalize the gauge kinetic term as

. In this convention, the effective charge entering the covariant derivative is

, so consistency with

implies

. Hence

(ii)

From the symplectic flux sector. The minimal symplectic flux corresponds to the action of a minimal coherent configuration. Dynamically this is expressed through the phase stiffness

integrated over the effective support measure

:

where

denotes the effective support volume of the minimal coarse-grained cell. The product

has the correct dimension of action.

2.3.2. Stationarity CONDITION

For self-consistency, the two expressions (

6) and (

7) must coincide at a physical, RG-stationary point

. We therefore impose

(Using

and

, the derivative condition gives

, hence

and

.) In the scheme (

5) this yields

Different renormalization schemes change only the numerical coefficient in

but preserve the existence of a finite stationary point. A full step-by-step derivation of this result is provided in Appendix C.

2.3.3. Final Identification

Substituting these results back into either (

6) or (

7), we find that the action scale

S is fixed to a unique, nontrivial value:

This dynamically selected, RG-invariant scale is identified with the physical Planck constant. The identification is unique and robust under changes of renormalization scheme (which shift only numerical prefactors of order unity without affecting the existence of the stationary closure). Hence we obtain the structural relation

Equation (

10) holds in model units; conversion to SI units is discussed below.

Remark 1

(On the robustness of the result). The mechanism of RG-stationary reconciliation is a structural feature of the framework. Numerical coefficients in the final relation (such as the factor 2 in and the value ) are specific to the minimal model considered here (a single scalar field in the scheme with ). Different field contents or renormalization schemes may alter these prefactors, but the stationary closure mechanism itself remains intact. The robust, model-independent prediction is the existence of a unique, finite RG-stationary point at which the topological action scale is fixed, yielding a structural relation of the form , with the proportionality constant set by the specific field content and renormalization scheme.

2.4. Units and Conventions

2.4.1. Normalization

The flux has units of action. Whether the primitive cycle is normalized to ℏ or is a matter of convention; the structural results are invariant under this choice.

2.4.2. Calibration to SI Units

Equation (

10) holds in model units. Recovering SI units requires a single metrological calibration:

where

is an action unit fixed by one standard experiment. Natural anchors are quantum electrical standards, such as flux quantization and the Josephson effect [

15,

16], the integer quantum Hall effect [

16], the flux quantum in superconductors [

17,

18,

19], and the 2019 SI redefinition of the kilogram via the Kibble balance [

20,

21,

22]. This completes the reconciliation:

ℏ is structurally derived, with only its unit normalization anchored by experiment.

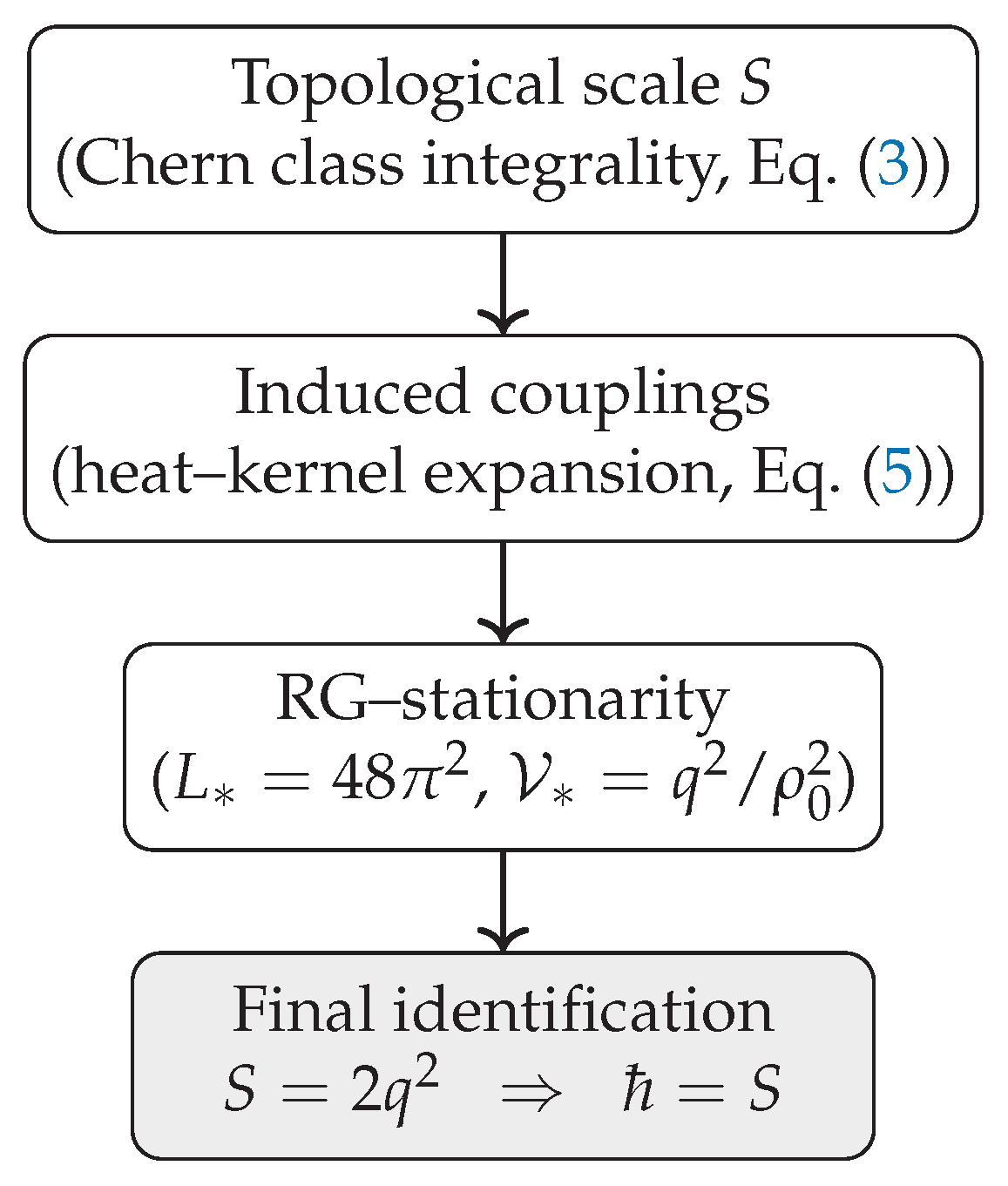

Figure 1.

Logical flow of the derivation: a topological action scale S is defined from geometric quantization, matched to induced couplings, and uniquely fixed by RG–stationarity. The resulting invariant is identified with Planck’s constant ℏ.

Figure 1.

Logical flow of the derivation: a topological action scale S is defined from geometric quantization, matched to induced couplings, and uniquely fixed by RG–stationarity. The resulting invariant is identified with Planck’s constant ℏ.

3. Experimental Consistency and Predictions

If

ℏ is the minimal symplectic flux (Sec.

Section 2), then laboratory phenomena that enforce quantized holonomy or minimal action should be consistent with the bound

. We illustrate this agreement in four canonical settings.

Notation. Throughout this section,

q denotes the physical charge of the probe (e.g.,

for electrons,

for Cooper pairs). This usage is distinct from the dimensionless fundamental

charge unit in Sec.

Section 2; here

q plays its empirical role in the standard experimental formulas.

3.1. Aharonov–Bohm Effect (1959)

For a charged particle (charge

q) encircling a magnetic flux

, the phase shift is [

23]

This follows from the holonomy of the prequantum

connection. Using

, the minimal nontrivial interference condition

implies

Thus the observed flux periodicity

[

24,

25] is consistent with the fact that the loop action cannot fall below one action quantum

h.

3.2. Josephson Effect (1962)

For Cooper pairs (

), the Josephson relation reads [

15]

Over one oscillation period

the phase winds by

, so the action advanced per cycle is

This corresponds to one quantum of action per oscillation, consistent with the operational basis for the Josephson constant

. In the structural relation (

10),

in model units, with the SI value obtained from a single metrological calibration

. The Josephson standard is therefore a natural anchor for fixing

.

3.3. Integer Quantum Hall Effect (1980)

The Hall conductance is quantized [

16]:

with

C the first Chern number of the Berry bundle over the Brillouin zone:

Each filled Landau level corresponds to an integer number of flux quanta piercing the sample,

. The associated loop action is

This reflects the integrality of the symplectic flux condition underlying

in Sec.

Section 2.1. The QHE is therefore consistent with the quantized action/flux principle in a transport observable.

(Interpretation.) The identification

is an interpretive link expressing that transport plateaus reflect quantized flux/action; it complements, rather than replaces, the standard TKNN–Chern analysis.

3.4. Quantum Speed Limits

Quantum speed limits (QSL) bound the minimal time

to evolve to an orthogonal state [

26,

27]:

Multiplying by the energy scale gives an action bound of order

ℏ:

Equivalently, for an effective low-energy Lagrangian density

(Sec.

Section 2.2),

with the integration taken over the RG-stationary support volume

(Sec.

Section 2.3). QSL are thus consistent with the minimal-action threshold in the time domain.

Across interference (Aharonov–Bohm), superconducting phase dynamics (Josephson), topological transport (integer QHE), and finite-time evolution (QSL), a consistent invariant pattern emerges: nontrivial quantum phenomena require at least of order ℏ. This is consistent with the structural statement that ℏ is the minimal symplectic flux and the RG-stationary quantum of action.

4. Calibration Formula

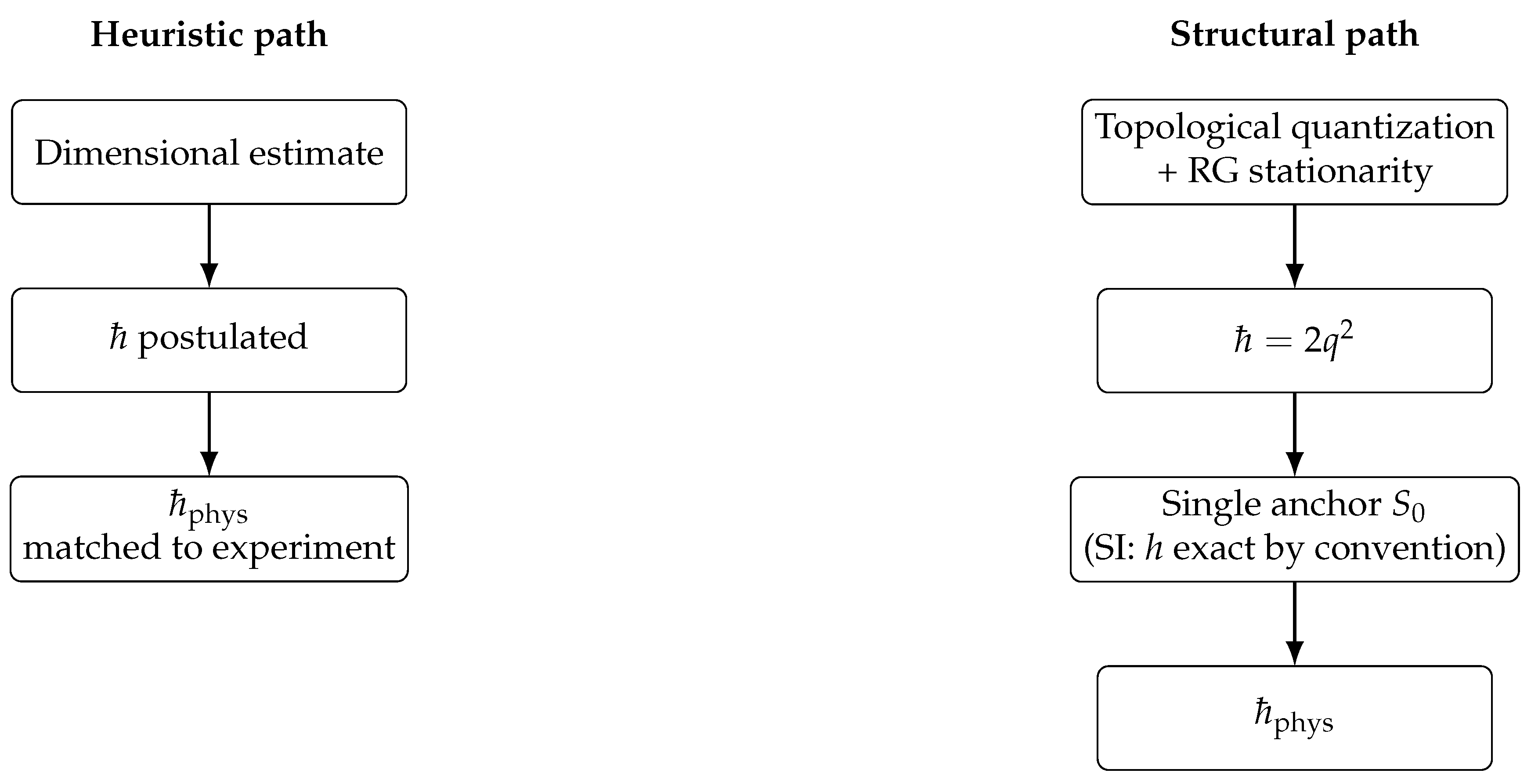

From dimensional estimates to structural derivation.

Earlier approaches often introduced Planck’s constant

ℏ through

dimensional estimates, for example formulas of the type

with

a vacuum amplitude and

a logarithmic scale factor. Such relations served only as heuristic normalizations:

ℏ was assumed

a priori and then adjusted to experiment. In contrast, the present framework closes the logical loop. From the topological normalization of the prequantum bundle and the RG–stationarity of the induced constants we obtain the

structural identity

in model units, without external input, where

q denotes the fundamental dimensionless

charge of the phase field.

To compare with experiment, a single dimensional scale must be fixed. We introduce an action unit

with dimension

, giving

The unit

is determined once by experiment; after that, all predictions follow without further adjustment. Equation (

24) therefore replaces heuristic normalization with a precise and transparent anchoring step.

Natural candidates for fixing are quantum standards that directly probe phase coherence and interference:

Josephson effect: the Josephson frequency–voltage relation

links

ℏ to the Josephson constant

[

15]. Its interference origin makes it a natural anchor for a phase–topological framework.

Flux quantum: the superconducting flux quantum

likewise reflects the quantization of action via phase winding around a loop. Its topological character provides a consistent anchor [

17].

Both anchors already enter the current SI definition of electrical units (via and ), ensuring full compatibility with existing metrological practice.

Equation (

24) is consistent with the present SI system, where

h is fixed as an exact constant by convention (CODATA 2019; BIPM SI Brochure, 9th ed.). In our framework this convention is interpreted as the choice of

, i.e. the metrological anchoring step that selects the numerical value of the action unit. The conceptual advance is that

ℏ is no longer a primitive axiom but a structural invariant derived from topology and RG closure.

The transition can be visualized as in

Figure 2: the traditional heuristic path runs linearly from a dimensional guess to

, whereas the structural path forms a closed loop, yielding

in model units and anchoring it to

by one metrological standard.

In this way, ℏ is reframed: not postulated, but deduced as an emergent invariant, with its physical value fixed by a single metrological anchor. This transforms ℏ from a primitive axiom into a structural constant derived within the model.

5. Future Outlook

The derivation of

ℏ as a structural invariant suggests that other fundamental constants may likewise admit structural explanations rather than purely axiomatic status. In particular, the induced couplings obtained through heat–kernel methods suggest possible extensions toward Newton’s constant

G and gauge couplings

in close analogy to the treatment of

ℏ. Exploring such extensions could help develop a broader structural account of dimensional constants in physics [

12,

14,

28].

The approach also resonates with information–theoretic and topological bounds. Entropy limits such as the Bekenstein bound [

29,

30] and the informational cost of erasure [

31,

32] can be reformulated within an action–based framework, suggesting a deeper unity between distinguishability, action quantization, and informational capacity. Moreover, the role of topological invariants in our derivation is directly compatible with holographic principles [

33,

34], indicating that gravitational dynamics may in principle be interpretable as effective responses of the underlying phase–topological substrate rather than as independent axioms.

A possible continuation is therefore the investigation of an emergent gravity program, in which spacetime curvature and Einstein dynamics could arise as induced phenomena. In such a setting, Newton’s constant G would not be simply postulated but could emerge as an effective coupling, paralleling the structural role of ℏ highlighted here.

Finally, the framework may also have practical implications in quantum information and computation. Because

ℏ emerges as the minimal action required for distinction, the theory provides a natural scale for quantum speed limits [

26,

27] and for the physical cost of information processing [

35]. This opens the possibility of applying the structural action principle not only to the foundations of physics but also to the design and ultimate limits of future quantum technologies.

| 1 |

Formally, if denotes the Lagrangian Grassmannian, the Gauss map has homotopy class measured by . |

Appendix A Appendix A: Topological Underpinnings — Integrality, Maslov Index, and Spin c Spin c

Appendix A.1. Prequantum Line Bundle and the Integrality Condition

A natural starting point for geometric quantization is the condition under which a symplectic manifold admits a prequantum line bundle. This establishes the topological integrality that ultimately constrains the quantum of action.

Let

be a connected symplectic manifold. A

prequantum line bundle is a Hermitian complex line bundle

equipped with a unitary connection ∇. For the bundle to be compatible with the symplectic structure, its curvature

must be proportional to the symplectic form

. We introduce a formal, a priori undetermined action scale

S to write this relation as

Here

is a real 2-form (multiplied by

i in the unitary representation, which we suppress for brevity). The constant

S has dimensions of action and represents the fundamental scale of prequantization. Its value is not postulated but is fixed dynamically in the main text.

Proposition A1

(Kostant–Souriau integrality).

A prequantum line bundle with curvature (A1) exists if and only if

Equivalently, for every closed oriented surface ,

Proof. By Chern–Weil theory, the first Chern class of

is represented by

in de Rham cohomology. The de Rham class comes from integral cohomology iff its period on every integral 2-cycle is integer, which is precisely (

A2). Conversely, if (

A2) holds, there exists a unitary line bundle with

; choosing a compatible connection yields (

A1). (See [

1,

2,

3].) □

Let denote a local connection 1-form, so that . In the Hamiltonian setting we write with the Poincaré–Cartan form .

Primitive cycles and normalization. Let

be a primitive 2-cycle, i.e.

. Then

, hence

Locally, in canonical coordinates

,

, and for a primitive loop with

one has

.

Remark A1

(Units and

conventions).

The flux has dimensions of action. Depending on normalization of the primitive generator, one may write or . All structural results are invariant under this convention (cf. main text, Sec. Section 2.4).

Appendix A.2. Holonomy and Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization

Having fixed the topological integrality, one can ask how it manifests in observable quantum phases. The answer comes from holonomy of the prequantum connection and the Bohr–Sommerfeld condition.

Let

be a closed loop. The prequantum holonomy of

is

If

bounds a surface

, then by Stokes and (

A1)

. Requiring single-valuedness of prequantum wavefunctions expresses the condition

which is the uncorrected Bohr–Sommerfeld condition ensuring

.

Appendix A.3. Maslov Index and EBK Quantization

Bohr–Sommerfeld quantization is only the first approximation. To capture corrections and stability of semiclassical states, the Maslov index and the EBK rule refine the picture.

Let

be a Lagrangian submanifold (

). For a closed curve

, its

Maslov index is the winding number of the determinant phase of a symplectic frame along

.

1 The Maslov class

pairs with

to give

[

36].

With half-form (metaplectic) correction the quantization rule becomes the Einstein–Brillouin–Keller (EBK) condition [

6]:

For the 1D harmonic oscillator,

, giving

. See also [

3,

13] for modern expositions.

Remark A2

(Minimal action threshold).

While EBK yields system-dependent shifts , the existence of a nonzero minimal quantum of action is topological and model-independent: it follows from integrality of and the primitive cycle , see (A3). The inequality used in the main text has this universal origin.

Appendix A.5. From Integrality to the Minimal Action Quantum

We now connect the abstract integrality condition directly with the existence of a universal minimal quantum of action. This shows how topology enforces the threshold .

Lemma A1

(Absolute normalization via a primitive cycle).

If is integral, then there exists a primitive 2-cycle with . For such , , hence (A3).

Proposition A2

(Holonomy, Maslov correction, and the threshold).

Let γ be a closed curve in a Lagrangian , and Σ a capping surface with . Then the phase of a half-form corrected state transported along γ is

Bohr–Sommerfeld reproduces EBK (A5). Existence of a primitive with implies a universal lower bound

Appendix A.6. Boundary Terms and Gauge Choices

Finally, one must check that the normalization is invariant under gauge redefinitions. This ensures that the action flux, not the choice of potential, carries the physical meaning.

In Hamiltonian form, is defined up to exact terms: . Such changes shift by on closed loops, leaving holonomy invariant. The flux form is gauge-invariant and is therefore our preferred normalization channel.

Appendix A.7. Dimensional Analysis

To close the circle, it is important to confirm that all constructions are dimensionally consistent. This guarantees that the quantization condition is physically meaningful.

By construction

, since

. The integrality condition (

A2) equates a dimensionless integer to

times an action flux. Consequently, the phase

is dimensionless and well defined, fully consistent with the dimensional assignments in the main text.

Remark. In the main text, the formal action scale S introduced here is dynamically identified with Planck’s constant ℏ via RG–stationarity. The role of this appendix is to show that the existence of a minimal nonzero quantum of action follows from topological integrality, independent of that identification.

Appendix B: Entropic Estimates — as Information Limits

We quantify how the structural threshold

for sustaining a distinguishable phase configuration translates into limits on information storage, processing, and transfer.

Scope and caveat. The following estimates are heuristic and exploratory: they are meant to illustrate the consistency of the

principle with established information–theoretic bounds, rather than to serve as rigorous derivations. The guiding principle,

is taken here as the minimal phase–action budget required for robust distinguishability (interference visibility, macroscopic coherence), as established in the main text and supporting notes on AB/Josephson phenomena and decoherence thresholds. Empirical instances where coherence disappears below this threshold are reviewed in App. C (AB, dc-SQUID, decoherence).

Appendix B.1. One Orthogonal Distinction Costs O(ℏ) of Action

Consider any physical operation that maps a state to an orthogonal state (creation of a reliably distinguishable alternative). The Mandelstam–Tamm [

26] and Margolus–Levitin [

27] bounds imply a minimal time for orthogonalization

at average available energy

. Therefore the

action consumed by a single orthogonalization satisfies

This dovetails with the phase–action threshold identified across AB/SQUID and decoherence settings: the appearance of a resolvable phase holonomy (or sustained coherence) requires an

action budget. For AB and dc-SQUID one finds explicitly

and

, so one flux quantum (

) yields

i.e. safely above threshold.

Appendix B.2. Minimal Action per Logical Operation and Landauer Erasure

Landauer’s principle demands work

to erase one bit [

31,

32]. Combining this with a QSL-time for a logically irreversible step gives

for protocols where the available energy per step does not exceed the dissipation budget (

). Thus any physically realized bit erasure or creation of a new orthogonal record consumes at least

of action. This is a direct information-theoretic restatement of the structural threshold on phase action.

Appendix B.5. Confinement and Bekenstein–Type Bound

If energy

E is confined to radius

R, causality limits the usable time window by a light-crossing scale

. The total action available inside one crossing is

. Since each reliably storable bit requires at least

of action, the number of storable bits (or the entropy in nats) obeys

A more refined relativistic treatment fixes the order-unity factor to

, yielding the standard Bekenstein bound [

29,

30]

In our language (

A9) is the macroscopic expression of the microscopic rule

: a finite causal region supplies a finite phase–action budget per crossing, hence a finite information capacity.

Appendix B.6. Mixed States, Mixtures, and Phase–Action Cost

For statistical mixtures, distinguishability is quantified by entropy (Shannon/von Neumann). Preparing or maintaining a mixture with entropy

H (bits) requires an action budget at least of order

(scaling estimate; cf. (

A7)). Operationally, every reliably retrievable bit of classical record must be backed by a phase configuration whose coherence survives above the

ℏ threshold throughout acquisition and storage cycles. Violations would amount to observing a process with

(black-list falsification).

Appendix B.7. Entropy Production Versus Action Inflow (Open Systems)

In open systems with decoherence rate

, the coherence time is

. If an observable distinction is supported by an energy gap

, the available phase action is

. Experiments show that interference visibility collapses once

, consistent with

as a structural threshold for ontological persistence of phase distinctions [

40]. This gives a practical rule for design:

either increase (phase lever) or suppress Γ (environmental coupling) so that , as interference visibility decays to the noise floor.

Appendix B.8. Summary and Falsifiability

Per distinction: each orthogonal record/operation costs ; thus is the structural threshold for persistent distinguishability.

Per information unit: , i.e. action budgets scale with entropy/algorithmic content.

Per rate/capacity: and, under confinement, (Bekenstein-type).

Violations (e.g. a reliably distinguishable process with total ) would falsify the framework; this is explicitly listed among the falsifiability criteria in Sec. 3.

Appendix C: Detailed Derivation of Planck’s Constant

This appendix presents the full technical derivation of Planck’s constant ℏ as obtained in the main text. All intermediate steps are shown explicitly to ensure reproducibility and mathematical transparency.

Appendix C.1. Two independent definitions of the action scale

Let

S denote the fundamental action scale defined by the prequantum connection. Two logically independent routes determine its value:

where

q is the fundamental

charge unit,

is the induced gauge coupling,

is the induced phase stiffness, and

is the coarse-grained volume of the minimal support cell.

Appendix C.2. Induced constants from the heat-kernel expansion

From the one-loop effective action [

8,

9,

10,

12,

14,

41]:

with

the UV cutoff and

the vacuum amplitude. Introduce

Then

Appendix C.3. RG-stationarity and Solution

The two channels (

A10) and () must coincide at a physical RG-stationary point

.

Appendix C.3.1. Step 1: The stationarity condition

We require stability under changes of scale:

Appendix C.3.2. Step 2: Calculating the derivatives

Appendix C.3.3. Step 3: Solving for V * and L *

The stationarity condition gives

Now enforce equality of the two channels :

Multiplying through gives

so

Then from (

A17):

Appendix C.4. Final Identification of ℏ

At the stationary point,

Thus the dynamically selected action scale is

Appendix C.5. Remarks

The value comes directly from Seeley–DeWitt coefficients in the scheme; other schemes shift only numerical prefactors.

The dual closure of the gauge and flux channels ensures no circularity: ℏ is fixed structurally, not assumed.

Conversion to SI requires one calibration:

where

is set by a single metrological reference (e.g. Josephson effect).

Appendix C.6. Summary

RG-stationarity uniquely selects and . At this point the gauge and flux routes coincide, yielding . We identify this structural scale with Planck’s constant, establishing ℏ as a derived invariant of phase topology and renormalization dynamics.

References

- Kostant, B. Quantization and Unitary Representations. In Lectures in Modern Analysis and Applications III; Taam, C.T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1970; Vol. 170, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, pp. 87–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souriau, J.M. Structure des systèmes dynamiques; Dunod: Paris, 1970. Reprint: Jacques Gabay, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse, N.M.J. Geometric Quantization, 2 ed.; Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Simon, B. Holonomy, the Quantum Adiabatic Theorem, and Berry’s Phase. Physical Review Letters 1983, 51, 2167–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proceedings of the Royal Society A 1984, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.B. Corrected Bohr–Sommerfeld Quantum Conditions for Nonseparable Systems. Annals of Physics 1958, 4, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniatycki, J. Geometric Quantization and Quantum Mechanics; Vol. 30, Applied Mathematical Sciences, Springer-Verlag: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrell, N.D.; Davies, P.C.W. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge University Press, 1982. [CrossRef]

- Vassilevich, D.V. Heat kernel expansion: User’s manual. Physics Reports 2003, 388, 279–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkey, P.B. Invariance Theory, the Heat Equation, and the Atiyah–Singer Index Theorem, 2 ed.; CRC Press, 1995.

- Mnev, P.; Wernli, K. Gluing formulae for heat kernels. Journal of Geometry and Physics 2025, 195, 105594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, S.L. Einstein gravity as a symmetry breaking effect in quantum field theory. Reviews of Modern Physics 1982, 54, 729–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gosson, M.A. Symplectic Methods in Harmonic Analysis and in Mathematical Physics; Vol. 7, Pseudo-Differential Operators, Birkhäuser: Basel, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. Soviet Physics Doklady 1968, 12, 1040–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, B.D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Physics Letters 1962, 1, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- v. Klitzing, K.; Dorda, G.; Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized Hall resistance. Physical Review Letters 1980, 45, 494–497. [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity, 2 ed.; McGraw–Hill, 1996.

- B. S. Deaver, J.; Fairbank, W.M. Experimental Evidence for Quantized Flux in Superconducting Cylinders. Physical Review Letters 1961, 7, 43–46. [CrossRef]

- Doll, R.; Näbauer, M. Experimental Proof of Magnetic Flux Quantization in a Superconducting Ring. Physical Review Letters 1961, 7, 51–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM). The International System of Units (SI). https://www.bipm.org/en/publications/si-brochure, 2019. Online 9th edition; updated 2022, available at BIPM website.

- Tiesinga, E.; Mohr, P.J.; Newell, D.B.; Taylor, B.N. CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2018. Reviews of Modern Physics 2021, 93, 025010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlamminger, S.; Steiner, R.L.; Haddad, D.; Newell, D.B.; Seifert, F.; Chao, L.S.; Liu, R.; Williams, E.R.; Pratt, J.R. A summary of the Planck constant measurements using a watt balance with a superconducting solenoid at NIST. Metrologia 2015, 52, L5–L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonov, Y.; Bohm, D. Significance of Electromagnetic Potentials in the Quantum Theory. Physical Review 1959, 115, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.T. Evidence for Aharonov–Bohm effect with magnetic field completely shielded from electron wave. Physical Review Letters 1986, 56, 792–795. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, M.; Weder, R. The Aharonov–Bohm effect and Tonomura et al. experiments: Rigorous results. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2009, 50, 122108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelstam, L.I.; Tamm, I.E. The Uncertainty Relation Between Energy and Time in Non-relativistic Quantum Mechanics. Journal of Physics (USSR) 1945, 9, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolus, N.; Levitin, L.B. The maximum speed of dynamical evolution. Physica D 1998, 120, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, A. Broken-Symmetric Theory of Gravity. Physical Review Letters 1979, 42, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Universal upper bound on the entropy-to-energy ratio for bounded systems. Physical Review D 1981, 23, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousso, R. The holographic principle. Reviews of Modern Physics 2002, 74, 825–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, R. Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process. IBM Journal of Research and Development 1961, 5, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H. The Thermodynamics of Computation—A Review. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1982, 21, 905–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Hooft, G. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. arXiv preprint gr-qc/9310026 1993. Essay dedicated to Abdus Salam, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.gr-qc/9310026. [CrossRef]

- Susskind, L. The World as a Hologram. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1995, 36, 6377–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Ultimate physical limits to computation. Nature 2000, 406, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslov, V.P. Theory of Perturbations and Asymptotic Methods; Moscow State University Press, 1965. English transl.: MIT Press, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Freed, D.S. Classical Chern–Simons on manifolds with boundary. In Geometry, Topology, and Physics; International Press, 1995; pp. 127–139.

- Hitchin, N.J. Lectures on special Lagrangian submanifolds. In Winter School on Mirror Symmetry, Vector Bundles and Lagrangian Submanifolds; American Mathematical Society / International Press, 2001; Vol. 23, AMS/IP Studies in Advanced Mathematics, pp. 151–182.

- Bremermann, H.J. Optimization through evolution and recombination. Self-Organizing Systems 1962, pp. 93–106.

- Zurek, W.H. Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics 2003, 75, 715–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. Sakharov’s induced gravity: A modern perspective. Modern Physics Letters A 2002, 17, 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).