Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

- The outbreaks reported in Paraíba, Pernambuco, Ceará and Rio Grande do Norte, along with the serological findings (Table 1 and Table 2) suggest the existence of a region of enzootic instability in the Northeast of Brazil, particularly in the semiarid region. In this area, prolonged droughts are common, and outbreaks tend to occur during the rainy season, coinciding with periods of increased Tabanidae abundance. This association persists despite the limited number of species identified in these states and the absence of studies addressing the seasonality of horseflies [53]. After an outbreak, the prevalence of animals with antibodies is high, but within 2 years the animals lose these antibodies and, apparently, the herd becomes susceptible again [11]. This state of enzootic instability in the semiarid region of the Northeast was also evidenced in a serological survey in the semiarid region of Paraíba, in which no animals with antibodies were found in 509 cows on 37 farms [23].

- b. In contrast, the presence of antibodies, or even low numbers parasite, shows that in many regions the disease is in enzootic stability. This is evident in areas like the Pantanal of Mato Grosso and in the North region, where the parasite was identified or outbreaks occurred in the 1970s and 1990s [77,90,91,93]. Subsequently, the presence of antibodies or the parasite (Table 3 and Table 4) suggests that the disease remains in enzootic stability due to the high population of hematophagous insects in the region throughout the year.

- c. Another region that appears to be well defined is the South, encompassing the states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná. Despite the presence of antibodies and parasite (Table 3 and Table 4), no outbreaks of the disease have been reported in this region. This is likely due to the temperate and subtropical climate, which only allows for seasonal activity of Tabanidae. Their reproduction is limited to warmer periods and ceases during the cold seasons, preventing the formation of large vector populations for sustained transmission. In subtropical and temperate areas of southern South America such as Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay, the absence of outbreaks can be partially explained by the consistently low population density of horse flies throughout the year and the ecological characteristics of the local biomes. Studies from these regions show that while vector activity occurs seasonally, the average number of horseflies captured per Malaise trap per week is significantly lower than in tropical regions [6,54,60]. For instance, in the Amazon Forest, the Adolpho Ducke Reserve reported averages exceeding 130 flies per Malaise trap per week [6], while the Colombian Amazon showed values close to 26 [80]. The annual average in the Pampa and Coastal Plain of Rio Grande do Sul was only 4.38 [54], and as low as 0.59 in livestock areas of Tacuarembó, Uruguay [60]. Even with intensive short-term sampling—such as a single summer week in the Coastal Plain of Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil using 98 Malaise traps—the peak observed was 37.57 flies per trap (RF Krüger, data not published), which is considered exceptional and not representative of typical long-term densities. This difference is closely related to biome types: tropical regions like the Amazon and the Cerrado have environmental conditions favorable to continuous reproduction of Tabanidae [6,31], while temperate ecosystems in the South, such as the Pampa and remnant Atlantic Forest areas, experience cold winters that limit Tabanidae activity and reproduction to a few warm months each year [54,60]. In contrast, horse fly populations in tropical climates remain present for longer periods and exhibit biannual population peaks [25]. Therefore, even in regions where T. vivax circulation has been confirmed by serological or molecular methods, vector populations are likely insufficient to maintain effective mechanical transmission, explaining the absence of clinical outbreaks in these southern areas.

- d. The Southeast region (states of Minas Gerais, Espírito Santo, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro), and parts of the Central West (Goiás) and Northeast (Bahia, Alagoas and Pernambuco, mainly in the Zona da Mata) is where the vast majority of outbreaks transmitted through the administration of oxytocin in zebu dairy cattle or their crosses have occurred. Trypanosomosis has acquired great economic importance in this region due to the losses it causes and all the necessary measures that must be taken to control it. In the Central-West region, in the Cerrado areas of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, the disease has not been observed; however, caution is still advised when introducing animals, especially on dairy farms that use oxytocin for milk release.

| State [Reference] | Breed | Production | Animal Introduction | Insects | Injectable Medication | Morbidity | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pará, Amapá 6 farmsa [77] |

NIb | NI | Yes | Tabanidae | NI | NI | NI |

| Mato Grosso [94] | NI | NI | NI | Tabanidae | NI | NI | NI |

| Tocantins [58] | Brahman | Beef cattle | Yes | Tabanidae | NI | 9/250 (3.6%) | NI |

| Paraíba [11] | Brown Swiss | Milking cows Calves |

Yes | Tabanidae | NI | 64/130 (49%) 32/100 (32%) |

11 (8.5%) 5/100 (5%) |

| Paraíba [12] Paraíba [12} |

Brown Swiss | Milking cows | Yes | Tabanidae S. calcitrans |

NI | 17/36 (47%) | 8/36 (22.2%) |

| NI | Milking cows | Yes | Tabanidae S. calcitrans |

NI | 10/75 (13.3%) | 7/75 (10.6%) | |

| Paraíba [14] 3 outbreaksa |

Holstein x Brown Swiss | Calves | Yes | Tabanidae | NI | 63-80% | 15-20% |

| São Paulo [17] | Girolando Holstein |

Milking cows and calves | Yes |

H. irritans S. calcitrans |

NI | 53/1080 (4.9%) | 31/1080 (2.9%) |

| Pernambuco [79] | NI | Milking cows | No | Hematophagous flies | NI | 22/80 (27.5%) |

3/80 (3.75%) |

| Ceará 15 | Guzerá x Holstein | Milking cows | NI | NI | NI | 48/210 (22.8%) | NI |

| Maranhão [78] | Girolando Holstein | Cows and calves | Yes | Tabanidae S. calcitrans |

Yes | 24/273 (8.79%) | 6/273 (2.1%) |

| State [Reference] | Breed | Production | Animal Introduction | Morbidity | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| São Paulo [52] | NIa | Milking Cows | Yes | 37/200 (18.5%) | 15/200 (7.5%) |

| Pernambuco [74] Pernambuco [74] |

Girolando NI |

Milking cowsb Milking cows |

NI NI |

25/83 (25.3%) 25/75 (33.3%) |

8/83 (9.6%) 20/75 (27.7%) |

| Sergipe [104] | NI | Milking Cows | Yes | 3/15 (20%) | NI |

| Pernambuco [3] Pernambuco [3] Alagoas [3] |

Girolando Girolando Girolando |

Milking cows Milking cows Milking cows |

Yes Yes Yes |

NIc NI NI |

30/60 (50%) 8/62 (NI 15/102 (14.7%) |

| Goaisc [8] | Girololando | Milking cows | Yes | 51/161 (31%) | 12/161 (22.7%) |

| Rio de Janeiro 24 12 outbreaks |

Girolando, Holstein |

Milking cows Dry cows |

Yes (in 9 of 12 farms) | 10%-90%b | 2.3%-43.3% |

| Minas Gerais [82] 10 outbreaks |

Girolando Holstein |

Milking cows | NI | NI | 0.55%- 41.7% |

| Espírito Santo [89] | Girolando | Milking cows | yes | 10/22 (45.5%) | NI |

| Goiás [10] 24 outbreaks |

Girolando, Gir, Holstein, Jersey Crossbreeds | Milking cows | Yes | 8.84%c | NI |

| Bahia [97] | Girolando | Milking cows | Yes | NI | 10% |

| Bahia 2022 [21] 5 outbreaks |

Girolando, Holstein, Gir | Milking cows | Yes | 34/94 (35%) | 0-18.9% |

| Minas Gerais [2] | Holstein | Milking cows | Yes | NI | 6/37 (16.2%) |

| Bahia [57] | NI | Milking cows | Yes | NI | 12/48 (25%) |

| State [Reference] | Species | Number | Technique | Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples (n) | Farms/municipalities | ||||

| Mato Grosso do Sul [62] | Bovine | 2508 | 7 municipalities | ELISA | 56%, |

| Pará [62] | Bovine | 1056 | 5 regions | ELISA | 30.7% |

| Pará [47] | Bovine | 246 | NI | ELISA | 93.1% |

| Minas Gerais [64] | Bovine | 152 | 1 | ELISA | 48.5-52.6%a |

| Minas Gerais [42] | Bovine | 327 | 36 | RIFI | 16.2% |

| Pernambuco [49] | Bovine | 2053 | NI | IFA | 13.93% |

| Alagoas [87] | Bovine | 199 | 4 municipalities | RIFI | 23.6% |

| Paraíba [23] | Bovine | 509 | 37 farms | IFA | 0 |

| Minas Gerais [70] | Bovine | 2185 | 2185 | RIFI | 2.38% |

| Minas Gerais [5] | Bovine | 400 | 40 | RIFI | (9.9%, 49.6% farms |

| Minas Gerais [46] | Bovine | 101 | 3 | RIFI | 63% |

| Parana [96] | Bovine | 400 | 40 farms | IFA | 0 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul-Pantanal [66] | Bovine | 400 | 5 | ELISA | 89.75 |

| Mato Grosso do Sul-Pantanal [81] | Bovine | 200 200 |

NI | ELISA | 98.5% adults 83.5% calves |

| Goias, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Mato grosso [105] | Bovine | 102 | NI | ELISA | 55%, 34.4, 55%,70% |

| Mato Grosso do Sul-Pantanal [36] | Bovine | 170 312 |

4 4 |

ELISA PCR-FFLB |

50.59% 34.61% |

| Sta Catarina [29] | Bovine | 146 | 3 | IFA | 39% |

| Rio Grande do Sul [86] | Bovine | 691 | 24 | RIFI | 24,6% |

| 14 states [34] | Bovine | 5114 | NI | ELISA | 56.5% |

| Maranhão [92] | Buffalo | 116 | 5 municipalities | ELISA | 79.31 |

| Santa Catarina [40] | Bovine | 310 | 6 | RIFI | 8% |

| State [Reference] | Species | Number | Technique | Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Farms | ||||

| Piaui [59] | Bovine | 78 | 1 | Microscopy | 1.3% |

| Amapá [90,91] | Buffalo | 125, 215 | NIa | Microscopy | 25%, 8.9% |

| Amapá [91] | Bovine | 210 | Microscopy | 7.6% | |

| Pantanal- Mato Grosso do Sul e Paraguay [30] | Bovine Buffalo Sheep |

355 43 83 |

9 2 2 |

PCR | 44.7% 34.8% 37.3% |

| Mina Gerais [19] | Bovina | 1 | 1 | Microscopy-PCR | NI |

| Maranhão [48] | Bovine | 31 | 1 | Microscopy | 3.2% |

| Rio Grande do Sul [28] | Bovine | 1 | 1 | Microscopy | NI |

| Maranhão [67] | Bovine | 171 283 |

NI NI |

PCR | 6.21% 1.06% |

| Pará [35] | Buffalo | 621b | 60 | PCR | 1.89% |

| Pará [45] | Buffalo Bovine |

89 61 |

3 2 |

FFLBb | 59.6% 44.3% , |

| Minas Gerais [95] | Bovine | 115 | 5 | ELISA LAMP Woo |

5.2% 4.3% 1.7%% |

| Santa Catarina [29] | Bovine | 146 | 3 | PCR | 39% |

| Rio de Janeiro [1] | Bovine | 389 | 15 | PCR | 11.6% |

3. Clinical Signs

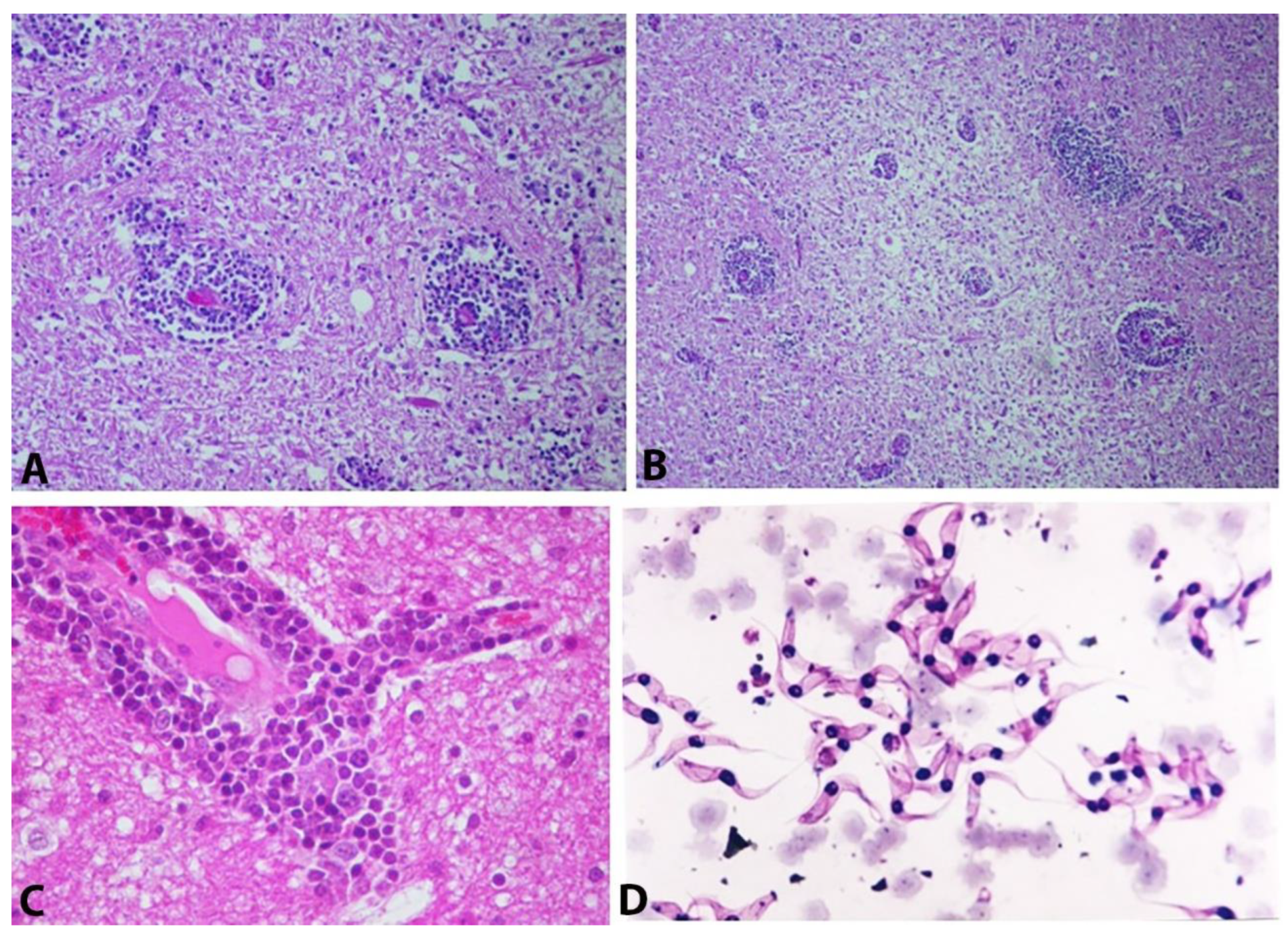

4. Pathology

5. Diagnosis

6. Control and Prophylaxis

- a)

- Heifers should be trained a few weeks before calving to familiarize themselves with the milking parlor. This involves simulating the udder preparation procedures, so that they become accustomed to the place and do not have difficulty releasing milk after calving.

- b)

- Before milking, the udder should be washed and the milk ejection reflex manually stimulated by massaging the teats.

- c)

- The application of exogenous oxytocin should be carefully planned and only be used in cows that truly have issues. This treatment is necessary when there is a risk of health problems in the mammary gland, caused by residual milk in the udder, which can lead to mastitis.

- d)

- A good milker should be able to identify animals that are difficult to milk, and should massage the udder during mechanical milking and reposition the teat cups as needed. Therefore, oxytocin administration should only be done in these animals.

- e)

- In Gir cows and their crossbreds, it is estimated that up to 35% of the cows in the herd may require oxytocin. Therefore, oxytocin administration should be carried out in these animals only.

- f)

- A long-term program should be established to select animals that can be milked without oxytocin.

- g)

- If oxytocin is administered, it should be administered with disposable needles and syringes or with needles and syringes that have been disinfected after each administration and in appropriate doses (<1 IU of oxytocin).

- h)

- It is necessary to define a medium or long-term program to stop using oxytocin, since cows that are being administered oxytocin do not produce milk letdown when the product is not applied. Therefore, it may be necessary to wait until the next lactation to stop using oxytocin.

7. Concluding remarks

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abreu, A.P.M.; Santos, H.A.; Paulino P.G., Jardim, T.H.A.; Costa, R.V.; Fernandes, T.A.; Fonseca, J.S.; Silva, C.B., Peixoto, M.P.; Massard, C.L. Unveiling Trypanosoma spp. diversity in cattle from the state e of Rio de Janeiro: A genetic perspective. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2024, 44:e07467, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alcindo, J.F.; Vieira, M.C.G.; Rocha, T.V.P.; Cardinot, C.B.; Deschk, M.; Amaral, G.G., et al. Evaluation of techniques for diagnosis of Trypanosoma vivax infections in naturally infected cattle in the Zona da Mata Mineira. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 31(1), e018021. [CrossRef]

- Andrade Neto, A.Q.; Mendonça, C.L.; Souto, R.J.C.; Sampaio, P.H.; Fidelis, O.L.; André, M.R.; Machado, R.Z.; Afonso, J.A.B. Diagnostic, clinical and epidemiological aspects of dairy cows naturally infected by Trypanosoma vivax in the states of Pernambuco and Alagoas, Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Med. 2019, 41, e094319. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, W.A.G.; Carvalho, C.G.V.; Marcondes, M.I.; Sacramento, A.J.R.; Paulino, P.V.R. Ocitocina exógena e a presença do bezerro sobre a produção e qualidade do leite de vacas mestiças. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci., São Paulo. 2012,49 (6), 465-470,.

- Barbieri, J.M.; Blanco, Y.A.C.; Bruhn, F.R.P.; Guimarães, A.M. Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma vivax, Anaplasma marginale, and Babesia bovis in dairy cattle. Cienc. Anim. Bras., Goiânia, 2016, 17(4), 564-573. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.D.G.V.; Henriques, A.L.; Rafael, J.A.; Fonseca, C.R.V.D. Diversidade e similaridade entre habitats em relação às espécies de Tabanidae (Insecta: Diptera) de uma floresta tropical de terra firme (Reserva Adolpho Ducke) na Amazônia Central, Brasil. Amazoniana, 2005, 18(3/4), 251-266.

- Barros, A.T.M.; Soares, F.G.; Barros, T.N.; Cançado, P.H.D. Stable fly outbreaks in Brazil: a 50-year (1971-2020) retrospective. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2023, 32(2), e015922 https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612023017.

- Bastos, T.S.A.; Faria, A.M.; Madrid, D.M.D.C.; Bessa, L.C.D.; Linhares, G.F.C.; Fidelis Junior, O.L.; Sampaio, P.H.; Cruz, B.C.; Cruvinel, L.B.; Nicaretta, J.E.; Machado, R.Z.; Costa, A.J.; Lopes, W.D.Z. First outbreak and subsequent cases of Trypanosoma vivax in the state of Goiás. Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 23, 366–371. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, T.S.A.; Faria, A.M.; Cavalcante, A.S.A.; Madrid, D.M.C.; Zapa, D.M.B.; Nicaretta, J.E.; Cruvinel, L.B.; Heller, L.M.; Couto, L.M.F.; Rodrigues, D.C.; Ferreira, L.L.; Soares, V.E.; Cadioli, F.A.; Lopes, W.D.Z. Infection capacity of Trypanosoma vivax experimentally inoculated through different routes in bovines with latent Anaplasma marginale. Exp. Parasitol. 2020, 211, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Bastos TSA; Faria A., Couto L.F.M., Nicaretta J.E., Cavalcante A.S.A, Zapa D.M.B.; Ferreira, L.L.; Heller, L.M.; Madrid, D.M.C.; Cruvinel, L.B.; Rossi, G. A.M., Soares, V.E.; Cadioli, F.A.; Lopes, W.D.Z. Epidemiological and molecular identification of Trypanosoma vivax diagnosed in cattle during outbreaks in central Brazil. Parasitology 2020, 147,1313–1319. [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.S.; Riet-Correa, F.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Madruga, C.R.; Simões, S.D.V.; Maia, T.F. Trypanosomiasis by Trypanosoma vivax in cattle in the Brazilian semiarid: Description of an outbreak and lesions in the nervous system. Vet. Parasitol. 2007,143(2),174-181. [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.S.; Bezerra, F.S.B.; Lira, R.A.; Carvalho, J.R.G.; Rosado Neto, A.M.; Petri, A.A.; Teixeira, M.M.G. Clinical, epidemiological and pathological signs of natural infection in cattle by Trypanosoma vivax in Paraíba, Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2008, 28(1),63-69. [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.S.; Oliveira, A.F.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Damasceno, C.A.R.; Oliveira, I.R.S.; Alves, H.M.; Paiva, E.S.; Brito, P.D.; Medeiros, J.M.F.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Texeira, M.M.G. Infection by Trypanosoma vivax in goats and sheep in the Brazilian semiarid region: from acute disease outbreak to chronic cryptic infection. Vet. Parasitol. 2009,165, 131–135. [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.S.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Olinda, R.G.; Silva, T.M.; Vale, R.G.; Câmara, A.C.; Teixeira, M.M. Highly debilitating natural Trypanosoma vivax infectious in Brazilian calves: epidemiology, pathology, and probable transplacental transmission. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 110(1): 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.S.; Freitas, C.I.A.; Da Silva, J.B.; Cavalcante, T.V.; De Paiva, K.A.R.; Lopes, F.C.; Lira, R. Clinical evaluation and reproductive indices of dairy cows naturally infected with Trypanosoma vivax. Semin. Agrar. 2017, 38, 3031-3038 https://doi.org/10.5433/1679- 0359.2017v38n5p3031.

- Brown W.C., Norimine J., Knowles D.P., Goff W.L. Immune control of Babesia bovis infection. Vet. Parasitol. 2006; 138:75–87. [CrossRef]

- Cadioli, F.; De Barnabé, P.A.; Machado, R.; Teixeira, M.C.A.; André, M.R.; Sampaio, P.H.; Fidélis Junior, O.L.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Marques, L.C. First report of Trypanosoma vivax outbreak in dairy cattle in São Paulo state, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2012, 21(2): 118-124. [CrossRef]

- Cadioli, F.A.; Fidelis, O.L.; Sampaio, P.H.; Santos, G.N.; André, M.R.; Castilho, K.J.G.A.; Machado, R.Z. Detection of Trypanosoma vivax using PCR and LAMP during aparasitemic periods. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 214(1-2), 174-177. PMid:26414906. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.U.; Abrão, D.C.; Facury Filho. E.J.; Paes, P.R.O.; Ribeiro, M.F.B. Occurrence of Trypanosoma vivax in Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zoot. 2008, 60, 769–771. [CrossRef]

- Castilho Neto, K.J.G.A.; Garcia, A.B.D.C.F., Fidelis Jr., O.L.; Nagata, W.B.; André, M.R.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Machado, R.Z.; Cadioli, F.A. Follow-up of dairy cattle naturally infected by Trypanosoma vivax after treatment with isometamidium chloride. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30(1) e020220. [CrossRef]

- Caymmi, L.G. Caracterização de surtos de infecção natural por Trypanosoma vivax em bovinos: aspectos clínicos, epidemiológicos e tratamento. Master thesis, Federal University of Bahia. Posgraduate Program in Animal Science. 2022, pp 121.

- Cook, D. A historical review of management options used against the stable fly (Diptera: Muscidae). Insects, 2020, 11(5), 313. [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.M.M.; Ribeiro, R.F.V.; Duarte, A.L.L.; Mangueira, J.M.; Pessoa, A.F.A.; Azevedo, S.S.; Barros, A.T.M.; Riet-Correa,F.; Labruna, M.B. Seroprevalence and risk factors for cattle anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and trypanosomiasis in a Brazilian semiarid region. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2013, 22(2), 207-213. [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.V.C.; Abreu, A.P.M.; Thomé, S.M.G.; Massard, C.L.; Santos, H.A.; Ubiali, D.G.; Brito, M.F. Parasitological and clinical-pathological findings in twelve outbreaks of acute trypanosomiasis in dairy cattle in Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports. 2020, 22:100466. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.V.D.; Rodrigues, G.D.; Lima, H.I.L.D.; Krolow, T.K.; Krüger, R.F. Tabanidae (Diptera) collected on horses in a Cerrado biome in the state of Tocantins, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2024, 33(2), e001924. [CrossRef]

- Couto L.F.M.; Heller, L.M.; Zapa, D.M.B.; de Moura, M.I.; Costa, G.L.; de Assis Cavalcante, A.S.; Ribeiro, N.B.; Bastos, T.S.A.; Ferreira, L.L.; Soares, V.E.; Lino de Souza, G.R.; Cadioli, F.A.; Lopes, W.D.Z. Presence of Trypanosoma vivax DNA in cattle semen and reproductive tissues and related changes in sperm parameters. Vet. Parasitol. 2022, 309, 109761 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2022.109761.

- Cuglovici, D.A.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Reis-Cunha, J.L.; Carvalho, A.U.; Ribeiro M.F. Epidemiologic aspects of an outbreak of Trypanosoma vivax in a dairy cattle herd in Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Vet Parasitol. 2010,169: 320-326. [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.S.; Costa, M.M.; Polenz, M.F.; Polenz, C.H.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Lopes S.TD.A.; Monteiro, S.G. Primeiro registro de Trypanosoma vivax em bovinos no Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Cienc. Rural. 2009, 39(8), 2550-2554. http://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782009005000189.

- Da Silva, A.S.; Molosse, V.L.; Deolindo, G.L.; Cecere, B.G.; Vitt, M.V.; Nascimento, L.F.N.; das Neves, G.B.; Sartor, J.; Sartori, V.H.; Baldissera, M.D.; Miletti, L.C. Trypanosoma vivax infection in dairy cattle: Parasitological and serological diagnosis and its relationship with the percentage of red blood cells. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2022, 166, 105495. [CrossRef]

- Dávila, A.M.; Herrera, H.M.; Schlebinger, T.; Souza, S.S.; Traub-Cseko, Y.M.; Using PCR for unraveling the cryptic epizootiology of livestock trypanosomosis in the Pantanal. Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 117(1-2): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- De Lima, H.I.L.; Krolow, T.K.; Henriques, A.L. Checklist of horse flies (Diptera: Tabanidae) from Taquaruçu, Tocantins, Brazil, with new records for the state. Check List. 2015, 11(2), 1596-1596. [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Gardiner, P.R. Epidémiologie de la trypanosome bovine (Trypanosoma vivax) en Guyane Française. Rev. Elev. Med. Vet. Pays Trop. 1993; 46(3), 463-470. PMid:7910693.

- Desquesnes, M.; Gonzatti, M.; Sazmand, A.; Thévenon, S.; Bossard, G.; Boulangé, A.; Gimonneau, G.; Truc, F.; Herder, S.; Ravel, S.; Sereno, D.; Jamonneau, V.; Jittapalapong, S.; Jacquiet, P.; Solano, P.; Berthier, D.R Review on the diagnosis of animal trypanosomoses. Parasites & Vectors 2022, 15:64 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05190-1.

- Donadon, A.E.S. Levantamento soroepidemiológico de Trypanosoma Vivax em bovinos no Brasil. MSc Tesis. Faculdade de Ciencias Agrárias e Veterinárias, UNESP. 2023, 37p.

- Dyonisio, G.H.S.; Batista, H.R.; Da Silva, R.E.; Azevedo, R.C.F.; Costa, J.O.J.; Manhães, I.B.O.; Tonhosolo, R.; Gennari, S.M.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Marcili, A. Molecular diagnosis and prevalence of Trypanosoma vivax (Trypanosomatida: Trypanosomatidae) in buffaloes and ectoparasites in the Brazilian Amazon region. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 58(1), 403-407. [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, J.T. Trypanosoma spp. em bovinos no pantanal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Msc Thesis. Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul. Campo Grande, Brazil. 2021, 90p.

- Faraz, A.; Waheed, A.; Nazir, M.M.; Hameed, A.; Tauqir, N.A.; Mirza, R.H.; Ishaq, H.M.; Bilal, R.M. Impact of oxytocin administration on milk quality, reproductive performance and residual effects in dairy animals – A review. Punjab University Journal of Zoology. 2020, 35(1), 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira A.V.F.; Ferreira, A.V.; Garcia, G.C.; de Araújo, F.F.; Nogueira, L.M.; Bittar, J.F.F.; Bittar, E.R.; Padolfi, I.A.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Galdino, A.S.; Araújo, M.S.S. Methods applied to the diagnosis of cattle Trypanosoma vivax Infection: An overview of the current state of the art. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2023, XXXX, XX, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, O.L.; Sampaio, P.H.; Machado, R.Z.; André, M.R.; Marques, L.C.; Cadioli, F.A. Evaluation of clinical signs, parasitemia, hematologic and biochemical changes in cattle experimentally infected with Trypanosoma vivax. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2016, 25(1): 69-81. [CrossRef]

- Fiorin, F.E.; Casa, M.S.; Griebeler, L.B.; Goedel, M.F., Ribeiro, G.S.N.; Nascimento, L.F.N., das Neves, J.B.; Fonteque, G.B.; Miletti, L.C.; Saito, M.E.; Fonteque, J.H. Molecular and serological survey of Trypanosoma vivax in Crioulo Lageano Cattle from southern Brazil. Braz; J. Vet. Parasitol. 2025, 34(1), e019424 | https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612025019.

- Foil, L.D.; Hogsette, J. A. Biology and control of tabanids, stable flies and horn flies. Revue Scientifique et Technique-Office international des Épizooties. 1994, 13(4), 1125-1158.

- Frange, R.C.C.; Bittar, J.F.F.; Campos, M.T.G. Tripanossomíase em vacas da microrregião de Uberaba – MG: estudo soroepidemiológico. Revista Encontro de Pesquisa em Educação, Uberaba. 2013. 1(1), 3.

- Galiza, G.J.N.; Garcia, H.A.; Assis, A.C.O.; Oliveira, D.M.; Pimentel, L.A.; Dantas, A.F.M.; Simões, S.V.D.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Riet-Correa, F. High mortality and lesions of the central nervous system in trypanosomosis by Trypanosoma vivax in Brazilian hair sheep. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 182: 359-363. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.A., Rodrigues, A.C.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Bengaly, Z.; Minervino, A.H.; Riet-Correa, F.; Machado, R.Z.; Paiva, F.; Batista, J.S.; Patrick, R.N.; Hamilton, B.; Teixeira, M.G. Microsatellite analysis supports clonal propagation and reduced divergence of Trypanosoma vivax from asymptomatic to fatally infected livestock in South America compared to West Africa. Parasit Vectors 2014, 7(210), 1-13. PMid:24885708. [CrossRef]

- Garcia Pérez, H.A.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Pivat, I.H.V.; Fuzato, A.C.R.; Camargo, E.P.; Minervino, A.H.H.; Teixeira, M.M.G. High Trypanosoma vivax infection rates in water buffalo and cattle in the Brazilian Lower Amazon. Parasitol Int. 2020, 79, 102162. [CrossRef]

- Germano, P.H.V.; Edler, G.E.C.; Da Silva, A.A.; Lopes, L.O. Prevalência de Trypanosoma vivax em bovinos no município de Patos de Minas/MG. Rev. Acad. Ciênc. Anim. 2017;15(2):S433-434. [CrossRef]

- Guedes Junior, D.S.; Araújo, F.R.; Silva, F.J.M.; Rangel, C.P.; Barbosa Neto, J.D.; Fonseca, A.H. Frequency of antibodies to Babesia bigemina, B. bovis, Anaplasma marginale, Trypanosoma vivax and Borrelia burgdorferi in cattle from the Northeastern region of the State of Pará, Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2008, 17(2), 105- 109, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, R.M.S.N.C.; Feitosa Júnior, A.B.; Santos, H.P.; Abreu-SilvaI, A.L., Santos, A.C.G. Biometry of Trypanosoma vivax found in a calf in the state of Maranhão, Brazil. Ciência Rural, Santa Maria, 2008, 38(3), 833-835. [CrossRef]

- Guerra N.R., Monteiro M.F.M., Sandes H.M.M., Cruz N.L.N., Ramos C.A.N., Santana V.L.A., Souza M.M.A. & Alves L.C. Detecção de anticorpos IgG anti-Trypanosoma vivax em bovinos através de imunofluorescência indireta. Pesq.Vet. Bras. 2013, 33(12) 1423-1426. [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.M; Bastos, T.S.A.; Zapa, D.M.B.; de Morais, I.M.L.; Salvador, V.F.; Leal, L.L.L.L.; Couto, L.F.M.; Neves, L.C.; Paula, W.E.F.; Ferreira, L.L.; de Barros, A.T.M.; Cançado, P.H.D.; Machado, R.Z.; Soares, V.E.; Cadioli, F.A.; Krawczak, F.S.; Lopes, W.D.Z. Evaluation of mechanical transmission of Trypanosoma vivax by Stomoxys calcitrans in a region without a cyclic vector. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 96 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-023-08102-z.

- Jones, T.W.; Dávila, A.M. Trypanosoma vivax - out of Africa. Trends Parasitol. 2001, 17(2), 99-101. [CrossRef]

- Koether, K.; Albuquerque, A.L.; Zakia, L.S.; Rodrigues, F.P.; Takahira, R.K.; Munhoz, A.K.; Oliveira Filho, J.P.; Borges, A.S. Ocorrência de Trypanosoma vivax em bovinos leiteiros no estado de São Paulo. Rev. Acad. Ciênc. Anim. 2017; Supl 2, 15(2), S565-566.

- Krolow, T. K.; Carmo, D.D.D.D.; Oliveira, L.P.; Henriques, A.L. The Tabanidae (Diptera) in Brazil: Historical aspects, diversity and distribution. Zoologia, Curitiba. 2024, 41, e23074. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, R.F.; Krolow, T.K. Seasonal patterns of horse fly richness and abundance in the Pampa biome of southern Brazil. Journal of Vector Ecology, 2015, 40(2), 364-372. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Impacts of oxytocin (injection) hormone in milch cattle and human being. Impacts of oxytocin (injection) hormone in milch cattle and human being. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts. 2022. 10 (10), B325-B329.

- Lamoglia, M.A.; Garcez, N.; Cabrera, A.; López, R.D.; Rentería, I.C.D.; Rojas-Ronquillo, R. Behavior affected by routine oxytocin injection in crossbred cows in the tropics. R. Bras. Zootec. 2016, 45(8), 478-482. [CrossRef]

- Leal, S.M.L.; Sena, M.E.A.; de Lorenci, M.S.; da Cruz, T.C.; Almeida, L.C.; Gomes, A.R.; Teixeira, M.C.; Pereira, C.M. Surto de tripanossomíase em bovinos no sul da Bahia. Revista DELOS, Curitiba, 2025, 18(65), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Linhares, G.F.C.; Filho, F.C.D.; Fernandes, P.R.; Duarte, S.C. Tripanossomíase em bovinos no município de Formoso do Araguaia, Tocantins: relato de caso. Ciênc. Anim. Bras., Goiânia, 2006, 7(4), 455-460.

- Lopes, S.T.P.; Prado, B.D.S.; Martins, G.H.C.; Esmeraldo, H.; Bezerra, A.; de Sousa Filho, M.A.C.; Evangelista, L.S.D.M.; Souza, J.A.T.D. Trypanosoma vivax em bovino leiteiro. Acta Scientiae Veterinariae. 2018, 46, 287.

- Lucas, M.; Krolow, T.K.; Riet-Correa, F.; Barros, A.T.M.; Krüger, R.F.; Saravia, A.; Miraballes, C. Diversity and seasonality of horse flies (Diptera: Tabanidae) in Uruguay. Scientific Reports. 2020, 10(1), 401. [CrossRef]

- Macedo, S.N.; Santos, M.V. Uso de ocitocina em vacas leiteiras - Fev-13. Revista Leite Integral, Piracicaba-SP. 2013, 24 -27.

- Madruga, C.R.; Araújo, F. R.; Carvalcante-Goes, G.; Martins, C.; Pfeifer, I.B.; Ribeiro, L.R., Kessler, R.H.; Soares, C.O.; Miguita, M.; Melo, E.P.S.; Almeida, R.F.C.; Lima Junior, M.S.C. The development of an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for Trypanosoma vivax antibodies and its use in epidemiological surveys. Mem. Instit. Oswaldo Cruz. 2006.101(7), 801-807. PMid:17160291. [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, D F; Ross D.R. Epizootiological factors in the control of bovine babesiosis. Aust. Vet. J. 1972, 48(5):292-298. [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.F.; Madruga, C.R.; Koller, W.W.; Araújo, F.R.; Soares, C.O.; Kessler, R.H.; Melo, E.S.P.; Rios, L.R.; Almeida, R.C.F.; Lima Jr, M.S.C.; Barros A.T.M.; Marques L.C. Trypanosoma vivax infection dynamics in a cattle herd maintained in a transition area between Pantanal lowlands and highlands of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2008. 28(1), 51-56. [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, L.M.; Botteon, R.C.C.M.; Mello, M.R.B.; Botteon, P.T.L.; Vargas, D.F.R. Oxytoc.in application during milking and reproductive efficiency of crossbred cows. Rev. Bras. Med. Vet. 2016, 38(Supl.2),108-112.

- Mello, V.V.C.; Ramos, I.A.S.; Herrera, H.M.; Mendes, N.S.; Calchi, A.C.; Campos, J.B.V.; Macedo, G.C.; Alves, J.V.A.; Machado, R.Z.; André, M.R. Occurrence and genetic diversity of hemoplasmas in beef cattle from the Brazilian Pantanal, an endemic area for bovine trypanosomiasis in South America. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 66,101337. [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.A.; Barros, A.C.; Costa, F.B.; de Carvalho Neto, A.V.; Guerra, R.M.C.; Abreu-Silva, A.L. Bovine trypanosomiasis an emerging disease in Maranhão State-Brazil. Vect. Born. Zoon. Dis. 2011, 7, 853–856. [CrossRef]

- Melo Junior, R.D.; Bastos, T.S.A.; Heller, L.M.; Couto, L.F.M.; Zapa, D.M.B.; Cavalcante, A.S.A.; Cruvinel, L.V.; Nicaretta, J.E.; Iuasse, H.B.; Ferreira, L.L.; Soares, V.E.; de Souza, G.R.L.; Cadioli, F.A.; Lopes, W.D.Z. How many cattle can be infected by Trypanosoma vivax by reusing the same needle and syringe, and what is the viability time of this protozoan in injectable veterinary products? Parasitology. 2021, 149(2):1-35. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Melo Junior, R.D.; Bastos, T.S.A.; Couto, L.M.C.; Cavalcante, A.S.A; Beltran, D.M.; Zapa, D.M.B.; de Morais, I.M.L.; Heller, L.M.; Salvador, V.N.; Leal, L.L.L.L; Franco, A.O.; Miguel, M.P.; Ferreira, L.L.; Cadioli, F.A.; Machado, R.Z.; Lopes, W.D.Z. Trypanosoma vivax in and outside cattle blood: Parasitological, molecular, and serological detection, reservoir tissues, histopathological lesions, and vertical transmission evaluation. Res. Vet. Scien. 2024, 174, 105290. [CrossRef]

- Meneses, R.M. Tripanossomose bovina em Minas Gerais, 2011: Soroprevalência e fatores de risco. Tese Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. 2016, 61p.

- Mihok, S. The development of a multipurpose trap (the Nzi) for tsetse and other biting flies. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2002, 92(5), 385-403.

- Muita, J.W.; Bargul, J.L.; Makwatta, J.O.; Ngatia, E.M.; Tawich, S.K.; Masiga, D.K.; Getahun , M.N. Stomoxys flies (Diptera, Muscidae) are competent vectors of Trypanosoma evansi, Trypanosoma vivax, and other livestock hemopathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21(5): e1012570. [CrossRef]

- Nostrand, S.D.; Galton, D.M.; Erb H.N.; Bauman, D.E. Effects of daily exogenous oxytocin on lactation milk yield and composition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74:2119-2127. [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.S.B.; Souto, P.C.; Cruz, J.A.LO.; Guerra, N.R.; Guimarães, J.A.; Dantas, A.C.; Alves, L.C.; Rizzo, H. Surto de Trypanosoma vivax em rebanhos bovinos do estado de Pernambuco. Medicina Veterinária (UFRPE), Recife, 2017, 11(2), 96-101.

- Osório, A.L.A.R.; Madruga, C.R.; Desquesnes, M.; Soares, C.O.; Ribeiro, L.R.R.; Costa, S.C.G. Trypanosoma (Duttonella) vivax: its biology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and introduction in the New World-a review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2008,103 (1): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, F.; Lemos, R.A.A.; Nakazato, L.; Mori, A.E.; Brum K.E.; Bernardo, K.C.A. Trypanosoma vivax em bovinos no Pantanal do Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil: I. Acompanhamento clínico, laboratorial e anatomopatológico de rebanhos infectados. Revta. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2000, 9: 135-141.

- Pereira, L.J.; Abreu A.C.V. Ocorrência de tripanosomas em bovinos e ovinos na região amazônica. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 1978, 13 (3): 17-21,.

- Pereira, H.D.; Simões, S.V.D.; Souza, F.A.L.; Silveira, J.A.G.; Ribeiro, M.F.B.; Cadioli, F.A.; Sampaio, P.H. Clinical and epidemiological aspects and diagnosis of Trypanosoma vivax infection in a cattle herd, state of Maranhão, Brazil. Maranhão. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2018, 38 (5) 896-901.

- Pimentel, D.S.; Ramos, C.A.D.N.; Ramos, R.A.D.N.; de Araújo, F.R.; Borba, M.L.; Faustino M.A.D.G.; Alves, L.C. First report and molecular characterization of Trypanosoma vivax in cattle from state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Vet. Varasitol. 2012,185, 286–289.

- Pisciotti, I.; Miranda, D. R. Horse flies (Diptera: Tabanidae) from the “Parque Nacional Natural Chiribiquete”. Caquetá, Colombia. 2011, 104p. pisciotti_miranda.pdf.

- Ramos, I.A.S.; De Mello, V.V.C.; Mendes, N.S.; Zanatto, D.C.S.; Campos, J.B.V.; Alves, J.V.A.; Macedo, G.C.; Herrera, H.M.; Labruna, M.B.; Pereira, G.T.; Machado, R.Z.; André, M.R. Serological occurrence for tick-borne agents in beef cattle in the Brazilian Pantanal. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 29(1), e014919. [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.O.; Souza, F.R.; Albuquerque, A.S.; Monteiro, F.; Oliveira, L.; Raymundo, D.L.; Wouters, F.; Wouters, A.; Peconick, A.P.; Varaschin, M.S. Epizootic Infection by Trypanosoma vivax in cattle from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Korean J. Parasitol. 2019, 57(2), 191–195. [CrossRef]

- Riet-Correa, F.; Schild, A.L.; Lemos, R.A.A.; Borges, J.R.; Mendonça, F.; Machado, M. Doenças de ruminantes e eqüídeos. Editora MedVet, São Paulo. 2023. 4a Ed, Vol 1 and 2.

- Riet-Correa, F.; Micheloud, J.F.; Macchado, M.; Mendonça, F.S.; Schild, A.L.; Lemos, R.A.A. Intoxicaciones por plantas, micotoxinas y otras toxinas en rumiantes y équidos en Sudamérica. Davis-Thompson DVM Foundation. Formoor Lane, Gurnee,II 2024.

- Rochon, K.; Hogsette, J. A.; Kaufman, P.E.; Olafson, P.U.; Swiger, S. L.; Taylor, D.B. Stable Fly (Diptera: Muscidae)—Biology, Management, and Research Needs. J. Integrat. Pest Manag. 2021, 12(1), 38, 1–23 https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmab029.

- Samoel, G.V.A.; Fernandes, F.D.; Roman, I.J.; Rodrigues, B.T.; Miletti, L.C.; Bräunig, Patrícia ; Guerra, R.J.; Sangioni, L.A.; Cargnelutti, J.F.; Vogel, F.S. Detection of anti-Trypanosoma spp. antibodies in cattle from southern Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2024, 33(1), e013723 https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612024002.

- Santos, V.R. Ocorrência de anticorpos IgG anti-Trypanosoma vivax (Ziemann, 1905) em bovinos procedentes do estado de Alagoas, Brasil. Dissertação. Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Recife. 2013.36p.

- Schenk, M.A.M.; Mendonça, C.L.; Madruga, C.R.; Kohayagawa, A.; Araújo, F.R. Clinical and laboratorial evaluation of Nelore cattle experimentally infected with Trypanosoma vivax. Pesq. Vet. Brasil. 2001, 21(4),157-161. [CrossRef]

- Schmith, R.; Moreira, W.S.; Vassoler, J.M.; Vassoler, J.C.; Souza, J.E.G.B.; Faria, A.G.A.; Almeida, L.C.; Teixeira, M.C.; Marcolongo-Pereira, C. Trypanosoma vivax epizootic infection in cattle from Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 8(6), 629-632. [CrossRef]

- Serra Freire, N.M. Oiapoque – outro foco de Trypanosoma vivax no Brasil. Rev. Bras. Med. Vet. 1981, 4(4),30-31.

- Serra Freire, N.M., Reavaliação dos focos de Trypanosoma vivax Zieman 1905 em bovinos e bubalinos do Território Federal do Amapá (TFA). Rev. Fac. Vet. UFF. 1984,1, 41-45.

- Serra, T.B.R.; dos Reis, A.T.; Silva, C.F.C.; Soares, R.F.S.; Fernandes, S.J.; Gonçalves, L.R.; da Costa, A.P.; Machado, R.Z.; Nogueira, R.M.S. Serological and molecular diagnosis of Trypanosoma vivax on buffalos (Bubalus bubalis) and their ectoparasites in the lowlands of Maranhão, Brazil. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2024; 33(4), e003424 https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612024066.

- Shaw, J.J.; Lainson, R. Trypanosoma vivax in Brazil. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1972, 66, 25-32.

- Silva, R.; Silva, J.A.; Schneider, R.C.; Freitas, J.; Mesquita, D.P.; Ramirez, L.; Dávilda, A.M.R.; Pereira, M.E.B. Outbreak of trypanosomiasis due to Trypanosoma vivax (Ziemann, 1905) in bovine of the Pantanal, Brasil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 1996, 91, 561-562. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.B.; Silva, B.M.; Silva, L.T., Queiroz, W.C.C; Coelho, M.R.1; Silva, B.T.; Marcusso, P.F.; Baêta, B.A.; Machado, R.Z. First detection of Trypanosoma vivax in dairy cattle from the northwest region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2023, 75(1), 153-159. [CrossRef]

- Snak, A; Lara, A.A; Garcia, F.G.; Pieri, E.M.; da Silveira, J.A.G.; Osaki, S.C. Prevalence study on Trypanosoma vivax in dairy cattle in the Western region on the State of Paraná, Brazil. Semina: Ciências Agrárias, Londrina. 2018, 39 (1), 425-430. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.G.; Souza, R.C.; de Andrade, L.S. New detection of the occurrence of trypanosomiasis in a bovine herd in a rural property in the state of Bahia/BA – case report. Rev. Bras. Ci. Vet. 2021, 8(3), 138-141.

- Souza, T.F.; Cançado, P.H.D.; Barros, A.T.M. Attractivity of vinasse spraying to stable flies, Stomoxys calcitrans in a sugarcane area. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2021, 41:e06817. [CrossRef]

- Stephen, L.E. Trypanosomiasis: a veterinary perspective. Pergamon Press, New York. 1986, 533p.

- Tunnakundacha, S.; Desquesnes, M.; Masmeatathip, R. Comparison of Vavoua, Malaise and Nzi traps with and without attractants for trapping of Stomoxys spp.(Diptera: Muscidae) and tabanids (Diptera: Tabanidae) on cattle farms. Agricul. Nat. Resour. 2017, 51(4), 319-323. [CrossRef]

- Ujita, A.; El Faro, L.; Vicentini, R.R.; Lima, M.L.P.; Fernandes, L.O.; Oliveira, A.P. Veroneze, R.; Negrão, J.A. Effect of positive tactile stimulation and prepartum milking routine training on behavior, cortisol and oxytocin in milking, milk composition, and milk yield in Gyr cows in early lactation. Appl. An. Behav. Scien. 2021, 234, 105205. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, T.M.; Arellano, S.C. 1997. La tripanosomiasis bovina en América Latina y el Caribe. Veterinaria, Montevideo, 1997, 33(2), 17-21.

- Ventura, R.M.; Paiva, F.; Silva, R.A.M.S.; Takeda, G.F.; Buck, G.A.; Teixeira, M.M.G. Trypanosoma vivax: characterization of the spliced-leader gene for a Brazilian stock and species-specific detection by PCR amplification of an intergenic spacer sequence. Exp Parasitol. 2001, 99(1), 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, O.L.E.; Macedo, L.O.D.; Santos, M.A.B.; Silva, J.A.B.A.; Mendonça, C.L.D.; Faustino, M.A.D.G.; Ramos, C.A.N.; Alves, L.C.; Ramos, R.A.N.; Carvalho, G.A. Detection and molecular characterization of Trypanosoma (Duttonella) vivax in dairy cattle in the state of Sergipe, northeastern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2017, 24, 516–520. [CrossRef]

- Zanatto, D.C.S.; Gatto, I.R.; Labruna, M.B.; Jusi, M.M.G.; Samara, S.I.; Machado, R.Z.; André, M.R. Coxiella burnetii associated with BVDV (Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus), BoHV (Bovine Herpesvirus), Leptospira spp., Neospora caninum, Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma vivax in reproductive disorders in cattle. Braz. J. Vet. Parasitol, Jaboticabal, 2019, 28(2), 245-257. [CrossRef]

- Zapata Salas, R; Cardona Zuluaga, E.A., Reyes Vélez, J.; Triana Chávez, O.; Peña García, V.H.; Ríos Osorio, L.A.; Barahona Rosales, R.; Polanco Echeverry, D. Tripanosomiasis bovina en ganadería lechera de trópico alto: primer informe de Haematobia irritans como principal vector de T. vivax y T. evansi en Colombia. Rev Med Vet. 2017, 33:21-34. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).