1. Introduction

Plants produce secondary metabolites that serve as distinctive and valuable resources for industries such as pharmaceuticals, food additives, fragrances, and various other commercial sectors. These compounds, although not directly involved in primary biological functions like growth or reproduction, are typically synthesized at later stages of development. They often have unique chemical structures, are restricted to specific taxonomic groups, and are produced in small quantities as complex mixtures within chemical families.

Unlike primary metabolites, which are essential for an organism's survival, the absence of secondary metabolites may not lead to immediate death but can compromise long-term health, fertility, and adaptability. These substances frequently occur in a limited range of species within a given lineage and are crucial in ecological interactions, especially in defending plants from herbivores and other interspecies threats. Historically, humans have harnessed these compounds for use including medicine, cosmetics, and recreational substances [

1].

The olive tree (

Olea europaea L.) is emblematic of Mediterranean ecosystems, thriving in evergreen sclerophyllous habitats. It has evolved to endure two distinct and intense environmental stress periods: the hot, dry, high-light conditions of summer and the freezing temperatures of winter. Studies have extensively documented the anatomical and physiological traits, environmental adaptations, and economic significance of the olive tree. Its fruit and oil are central to the Mediterranean diet, with well-known health benefits [

2].

Adaptation to summer stress involves complex physiological responses [

3]. Under harsh conditions, such as extreme heat and limited water, photolysis is disrupted, leading to an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which causes oxidative damage and hampers photosynthesis. To cope, the plant shifts metabolic focus toward secondary metabolic pathways, a strategy that mitigates oxidative stress [

4].

Given the widespread distribution, ecological resilience, and economic value of the olive tree, this study aimed to explore how secondary metabolite production, particularly phenolics, responds to environmental stress typical of Mediterranean summer. By using three sustainable extraction methods—Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE), Enzymatic assisted extraction (EAE), and Microwave assisted extraction (MAE)—the study focused on measuring the total polyphenolic content in olive leaves through a time-sensitive lens, reflecting the dynamic nature of metabolite biosynthesis in relation to climatic stressors.

Olive leaves (OLs) are a rich natural source of bioactive compounds, notably polyphenols, which exhibit potent antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer activities [5-6]. The principal categories of polyphenols in olive leaves include simple phenols—primarily hydroxytyrosol (HT), flavonoids such as apigenin and luteolin glycosides, and secoiridoids, with oleuropein being the most abundant [7-8]. These secondary metabolites possess chemical structures highly suited for neutralizing free radicals, contributing to their strong antioxidant capabilities [9-10].

However, the concentration, composition, and bioavailability of polyphenols in olive leaves are influenced by a variety of genetic, environmental, and agronomic factors [

11]. The olive cultivar is one of the most significant determinants; for example, cultivars such as Koroneiki, Kalamata, and wild olive (

Olea europaea var. sylvestris) differ in their phenolic profiles and accumulation capacities [

12]. Environmental conditions such as temperature extremes, water stress, and solar radiation—characteristics typical of Mediterranean ecosystems—can sig nificantly modulate phenolic biosynthesis, often enhancing it as a stress-response mechanism [

13]. Additionally, leaf maturity plays a role, with younger leaves generally containing higher polyphenol concentrations [

14]. Other contributing factors include soil composition, altitude, and cultivation practices, including irrigation, pruning, and the use of organic versus conventional methods [

15]. Post-harvest conditions, such as drying methods and storage parameters, also affect phenolic compound stability and preservation [

16].

Given the health-promoting properties of olive leaf polyphenols, there has been growing interest in utilizing them for dietary supplements, functional foods, and cosmetics. Accordingly, several green extraction techniques have been developed to optimize the recovery of these compounds, including ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), and enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE) [17-18]. Studies have demonstrated that UAE enhances the extraction efficiency of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol by improving cell wall disruption and solvent penetration [

19]. MAE accelerates extraction kinetics, resulting in shorter processing times, increased extraction yields, and reduced solvent usage [

20]. EAE employs enzymes such as cellulase and pectinase to degrade plant cell walls, thereby facilitating the release of bound polyphenols [

21]. Furthermore, parameters such as solvent composition, pH, extraction time, temperature, and the solid-to-liquid ratio significantly influence the final phenolic profile of the extract [

22].

The aim of the present study is to compare three eco-friendly extraction methods while considering cultivation parameters and the effects of climate variability between cultivated groves and wild olive fields. Specifically, this study evaluates the total polyphenol content in leaves from four olive varieties collected from two distinct regions in Western Greece, applying different extraction protocols to assess their impact on yield and composition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Leaves from the olive trees were collected during September 2024. Three varieties from two different areas are collected. Koroneiki, Kalamata and a wild olive tree (

Olea europaea var. Silvestris) from Stamna, Greece and a wild tree (

Olea europaea var. Silvestris) from mountainous Paravola, Greece. The leaves are stored in freezer (-18 oC) until drying for 5 h. at 50

oC [

23]. The residual humidity was determined using a moisture analyzer, OHAUS MB35 Halogen (Switzerland), as presented in

Table 1. After that the dried leaves are pulverized (<700 μm) and stored in glass jars until used at room temperature in dark and dry place.

2.2. Climate Data

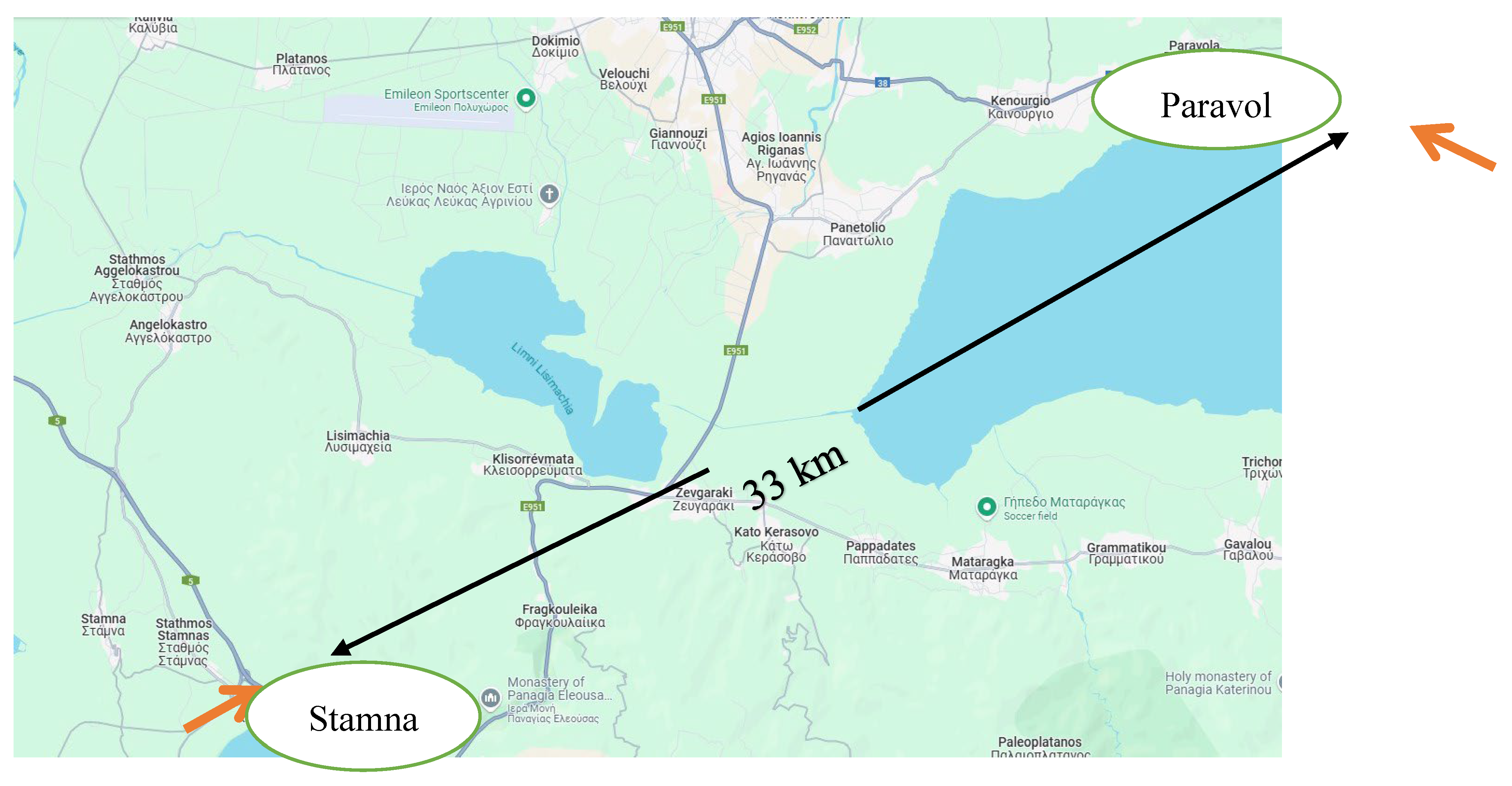

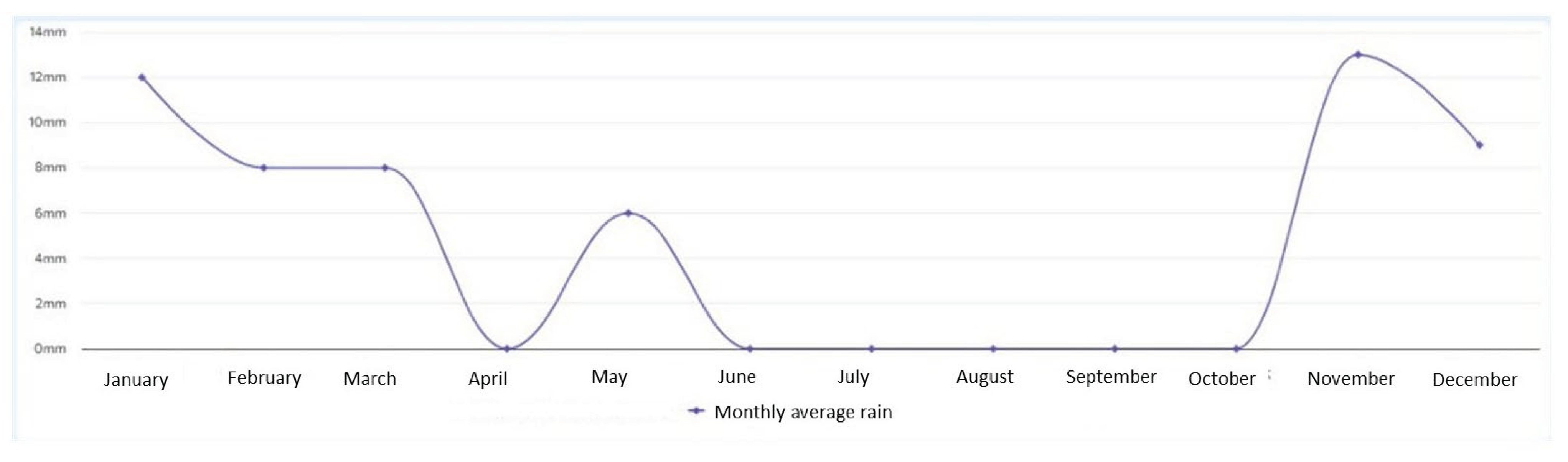

For the present study cultivation conditions were also analyzed. The climate data collection came from the site meteoblue.com, emy.gr and for the cultivation trees from Stamna the data collected from the digital counting system that the producer “Arxaia Oleneia” have on their olive groves, for the period of May to September 2024. The two areas analyzed (

Figure 1) were Stamna Aitoloakarnanias, Greece (160 m above sea) and the mountainous area of Paravola Aitoloakarnanias, Greece (400 m above sea) and the distance between them is approximately 33 km.

2.3 Chemicals and Reagents

For analytical purposes, the following reagents were used: 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH·) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Absolute ethanol (CH3CH2OH), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), and acetate buffer (CH3COONa × 3H2O) (Merck Darmstadt, Germany). Folin Ciocalteu reagent from Sigma-Aldrich. Gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydrobenzoic acid) 99% isolated from Rhus chinensis Mill. (JNK Tech. Co., Republic of Korea). For HPLC-MS/DAD analyses all solvents were HPLC grade; acetonitrile (99.9 % purity), water (≥99.9 % purity), methanol (>99.8 % purity), were obtained from ChemLab (Zeldegem, Belgium). All the other reagents and solvents used were of analytical grade.

2.4. Phytochemical Analyses

All measurements were performed with a SHIMADJU UV/VIS spectrophotometer (UV-1900, Kyoto, Japan) using 1 cm pathlength cuvettes. The content of total polyphenols (TPP) was determined using the method of Karabagias [

24] in the following modification: in a 5 mL volumetric flask, 0.20 mL of the leaves extract followed by 2.50 mL of distilled water and 0.25 mL Folin-Ciocalteu reagent were added. After 3 min, 0.50 mL of saturated sodium carbonate (Na

2CO

3, 30% w/v) were also added into the mixture. Finally, the obtained solution was brought to 5 mL with distilled water. This solution was left for 2 h in the dark at room temperature. The results were presented as equivalents of gallic acid (GAE).

The total antioxidant capacity was determined using the DPPH (free radical scavenging activity). DPPH assay was based on the method of Karabagias et al. (2016) modified as follows: 1.9 mL of absolute ethanol solution of DPPH·(1.34 × 10−4 mol/L) and 1 mL of acetate buffer 100 mmol/L (100 Mm) (pH = 7.10 ± 0.01) were placed in a cuvette, and the absorbance of the DPPH· was measured at t = 0 (A0). Subsequently, 0.1 mL of each extract studied was added to the above medium and the absorbance was measured at regular time periods, until the absorbance value reached a plateau (steady state, At). The reaction in all cases was completed in 15 min. Each sample was measured in triplicate (n = 3). For this antioxidant test ethanol and acetate buffer (2:1, v/v) were used as the blank sample.

2.5. Enzyme Preparations

The following commercial enzyme preparations were used: pectinolytic preparation Pectinex XXL and Viscozyme L. (Cellulase, Hemicellulase, Xylanase), all from Novozymes A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark.

2.6. Extraction Processes

The MAE was performed in a Juro-Pro microwave oven (20MX82-L, made in PRC). The microwave unit operated at a frequency of 2.45 GHz with a power of 700 W. Finely grounded (particle size < 700 μm) of olive leaves powder (OLP) (2 g) were added in distilled water (100 mL) and rehydrated for 60 min at 25 °C. After rehydration the extract produced at 86 °C temperature, with power 265 W and a duration of 5 min [

25].

The UAE was performed in an ultrasound system (Digital ultrasonic bath, Nahita) with a working frequency of 50 kHz and a power output of 120 W (Miliot Science, Finland). Finely grounded (particle size < 700 μm) of OLP samples (3 g) were mixed in distilled water (100 mL) for 60 min. 25 °C and treated in ultrasonic temperatures (65 °C) for 15 min. [

26]

EAE was performed according to Vardakas [

38]. Finely grounded (particle size < 700 μm) olive leaves (10 g) were mixed with water (100 mL), acidified (pH 4.0) with citric acid, and left for 1 h for rehydration at 25 °C. After pH adjustment (pH 4.0), the suspension (100.0 g) was placed in a 50 °C water bath (Memmert Schutzart DIN 40,050-IP 20, Germany) for 20 min before enzymes were added. After incubation at 50 °C for 30 min., the sample was placed in a boiling water bath for 10 min to inactivate the enzymes, then immediately cooled and finally filtered through a paper filter under vacuum.

All the extracts were stored in freezer ( -18 oC) until use.

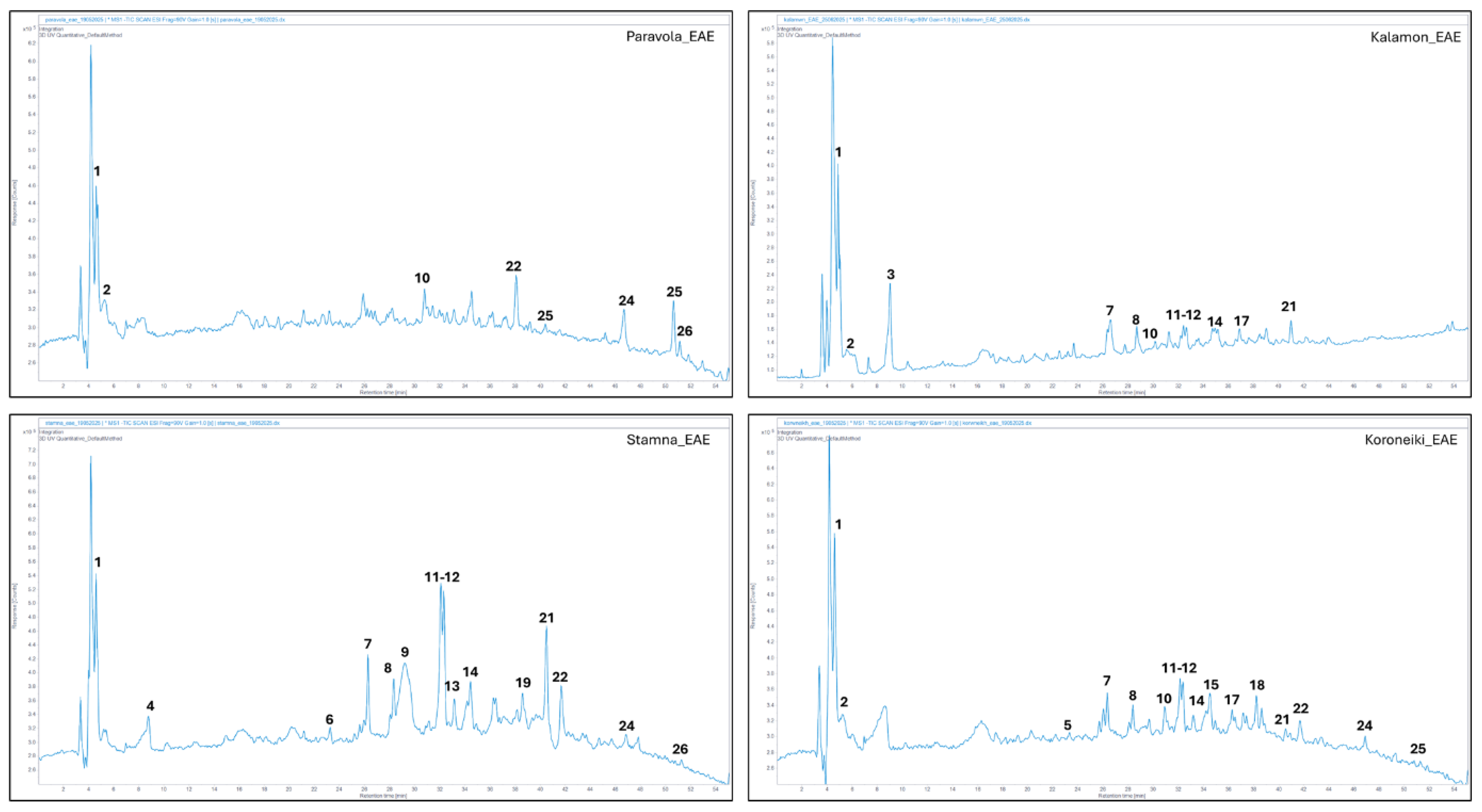

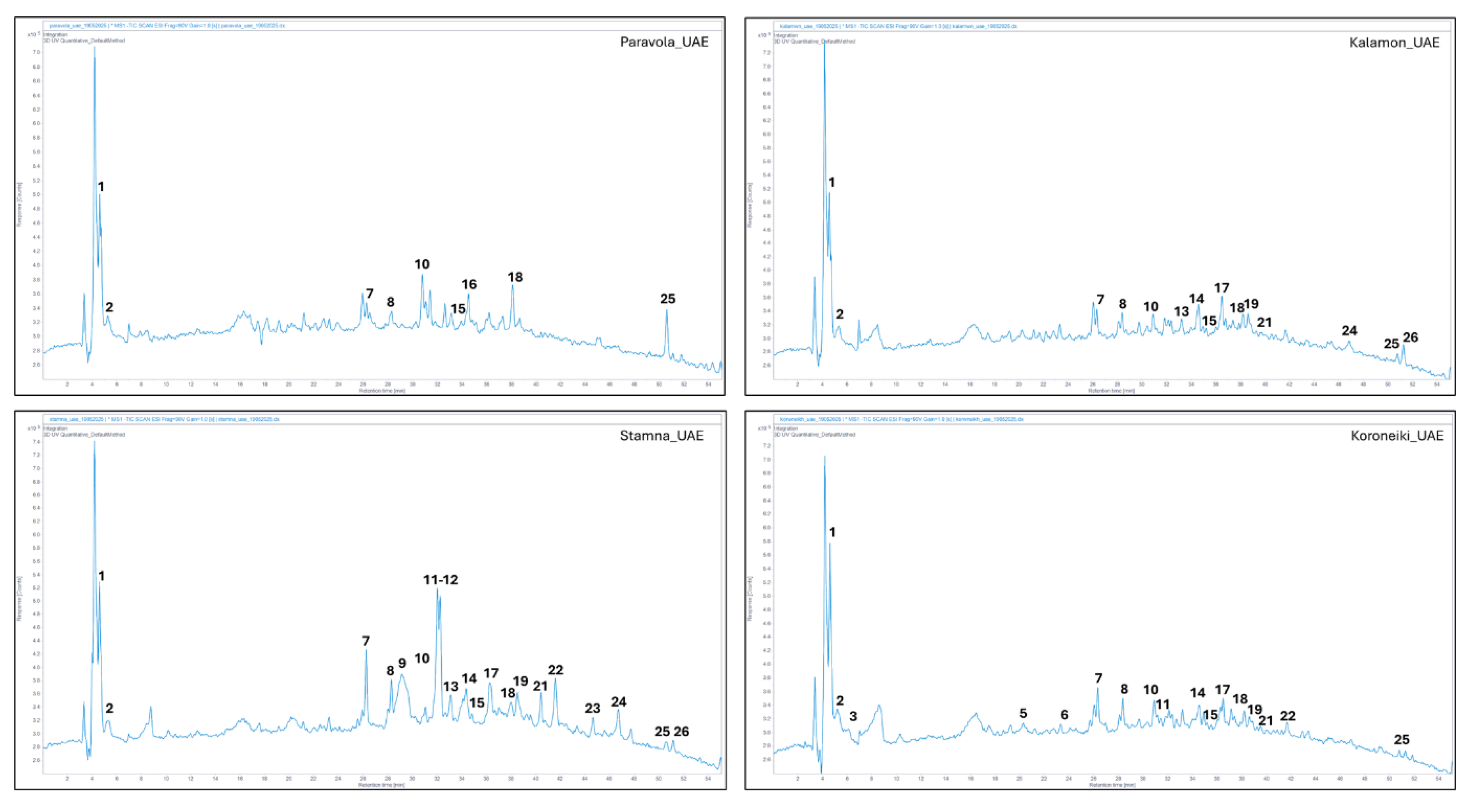

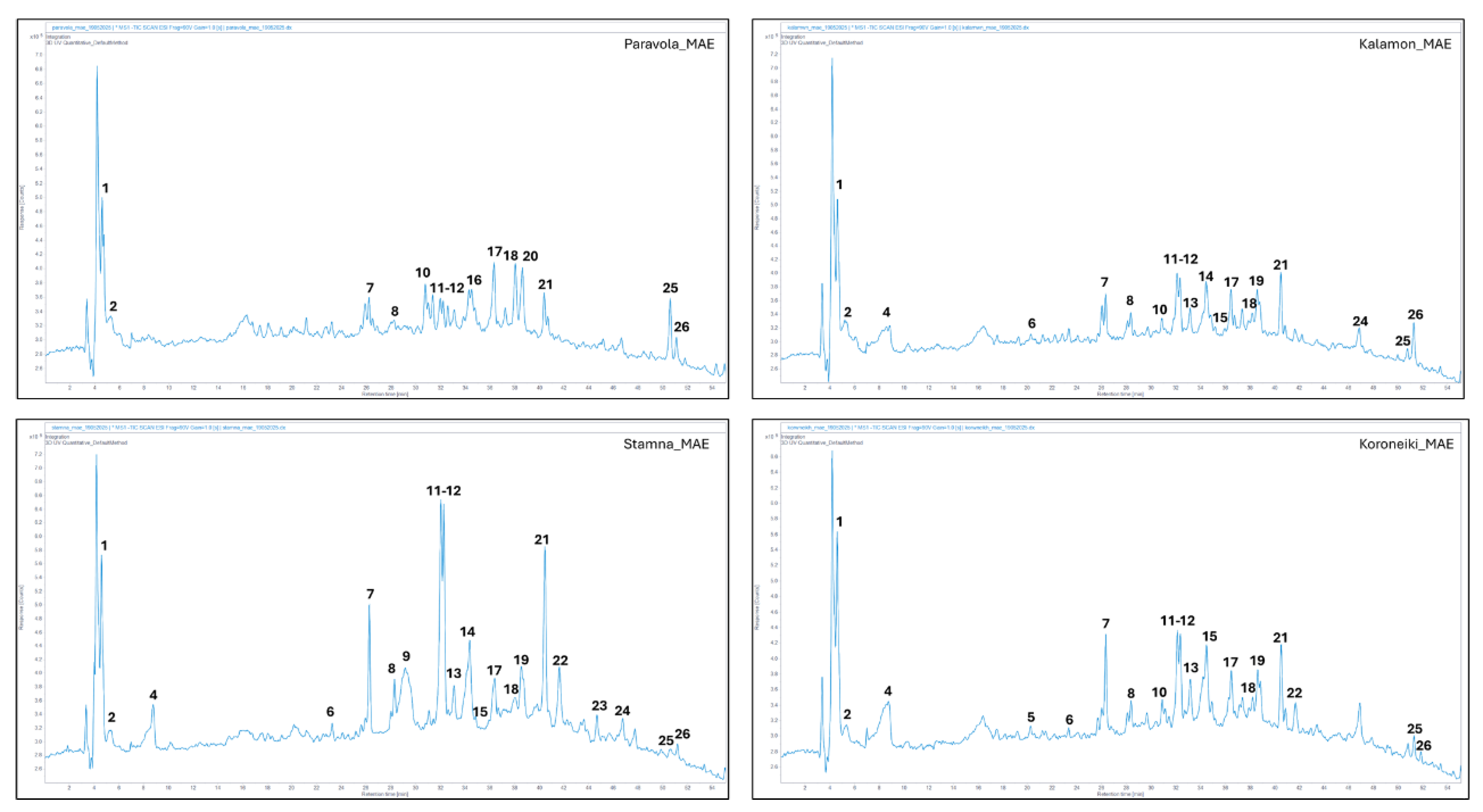

2.7. HPLC – DAD and HPLC – MSQ Analysis

A High-Performance Liquid Chromatography method combined with Diode Array Detection (HPLC–DAD) was developed to determine the main phenolic compounds in the olive leaves extracts. Specifically, the investigation of the phenolic composition of extracts was performed on a HPLC system (Thermo Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada) equipped with a SpectraSystem 1000 degasser, a SpectraSystem P4000 pump, a SpectraSystem AS3000 autosampler, and a UV SpectraSystem UV8000 Photo Diode Array (PDA) detector, by applying the IOC-proposed analytical method with some modifications. The IOC method was performed according to analytical conditions referred to in the IOC/T.20/Doc No. 29 method (International Olive Council, 2009) [

21], and they have been described in our previous work [

17]. Briefly, the separation of the components of the extracts was achieved on a reversed-phase Discovery HS C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) using a mobile phase consisting of 0.2% aqueous orthophosphoric acid (A) and MeOH/ACN (50:50 v/v) (B), at flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and ambient temperature. The injection volume was held constant at 20 μL. The applied gradient elution was as follows: 0 min, 96% A and 4% B; 40 min, 50% A and 50% B; 45 min, 40% A and 60% B; 60 min, 0% A and 100% B; 70 min, 0% A and 100% B; 72 min, 96% A and 4% B; 82 min, 96% A and 4% B. Chromatograms were monitored at 280 nm.

To identify additional phenolic compounds and obtain further data on the bioactive content of olive leaf extracts, a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography system coupled with a single quadrupole Mass Spectrometer was employed. Specifically, the LC-MSQ analyses were performed on an LC–MS system consisting of an Agilent 1260 infinity II HPLC system coupled to a MSQ single quadrupole mass spectrometer detector with electrospray ionization interface. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a reversed-phase Discovery HS C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) using a mobile phase consisting of 0.2% aqueous formic acid (A) and MeOH/ACN (50:50 v/v) (B), at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min and ambient temperature. The injection volume was held constant at 20 μL. The applied gradient elution was as follows: 0 min, 96% A and 4% B; 40 min, 50% A and 50% B; 45 min, 40% A and 60% B; 60 min, 0% A and 100% B; 70 min, 0% A and 100% B; 72 min, 96% A and 4% B; 82 min, 96% A and 4% B. Mass spectra were obtained in negative ion mode with an Electrospray ionization (ESI) source. The ESI conditions were as follows: Gas temperature 350 oC; Capillary Voltage 3000 V; Gas flow 11 L/min; Nebulizer pressure 40 psi, using as nebulizer gas nitrogen. The proposed elemental composition (EC) and identification of phenolic compounds were determined using spectrometric data from standard compounds and existing “in-house” databases

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The results reported in the present study are the mean values of at least three analytical determinations and the coefficients of variation expressed as the percentage ratios between the standard deviations and the mean values were found to be <5% in all cases. The means were compared using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test at a 95% confidence level.