Submitted:

29 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Chemicals and Reagents

Enzyme Preparations

Enzyme-Assisted Extraction

Phytochemical Analyses

Experimental Design

(1)

(1)

| Factor | Minima | Centre point | Maxima | Axial point. a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme dose (%E/Sa) – Х1 |

0.02 | 0.1 | 0.18 | -a = -1 +a = +1 |

| Time (min.) – X2 | 30 | 120 | 210 | -a + = -1 +a = +1 |

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Selection of the Mixture of Enzyme Preparations

Optimization of the Process Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT-FAO, 2016. Statistical database. Accessed on December 2. <bold>2016</bold>. http://www.fao.org.

- Proietti, P., Nasini, L., Reale, L., Caruso, T., Ferranti, F. Productive and vegetative behavior of olive cultivars in super high-density olive grove. Scientia Agricola, <bold>2015</bold>, 72, 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Rosello-Soto, E., Barba, F.J., Parniakov, O., Galanakis, C.M., Lebovka, N., Grimi, N., Vorobiev, E. High voltage electrical discharges, pulsed electric field, and ultrasound-assisted extraction of protein and phenolic compounds from olive kernel. Food Bioprocess Tech, <bold>2015</bold>, 8, 885- 894. [CrossRef]

- Rui M.S. Cruz, Romilson Brito, Petros Smirniotis, Zoe Nikolaidou, Margarida C. Vieira. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Olive Leaves Using Emerging Technologies. Ingredients Extraction by Physicochemical Methods in Food, <bold>2017</bold>, 441- 461. [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M., Şahin, S. Effects of geographical origin and extraction methods on total phenolic yield of olive tree (Olea europaea) leaves. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng., <bold>2013</bold>, 44, 8–12. [CrossRef]

- Cherng, J.M., Shieh, D.E., Chiang, W., Chang, M.Y., Chiang, L.C. Chemopreventive effects of minor dietary constituents in common foods on human cancer cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., <bold>2007</bold>, 71, 1500–1504. [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, F., Mechri, B., Dabbou, S., Dhibi, M., Hammami, M. The efficacy of phenolics compounds with different polarities as antioxidants from olive leaves depending on seasonal variations. Ind. Crops Prod., <bold>2012</bold>, 38, 146–152. [CrossRef]

- Abaza, L., Youssef, N.B., Manai, H., Haddada, F.M., Methenni, K., Zarrouk, M. Chétoui olive leaf extracts: influence of the solvent type on phenolics and antioxidant activities. Grasas Aceites, <bold>2011</bold>, 62, 96–104. [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.H. Cardioprotective and neuroprotective roles of oleuropein in olive. Saudi Pharm. J., <bold>2010</bold>, 18, 111–121. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G., Yin, Z., Dong, J. Antiviral efficacy against hepatitis B virus replication of oleuropein isolated from <italic>Jasminum officinale L. var. grandiflorum</italic>. J. Ethnopharmacol., <bold>2009</bold>, 125, 265–268. [CrossRef]

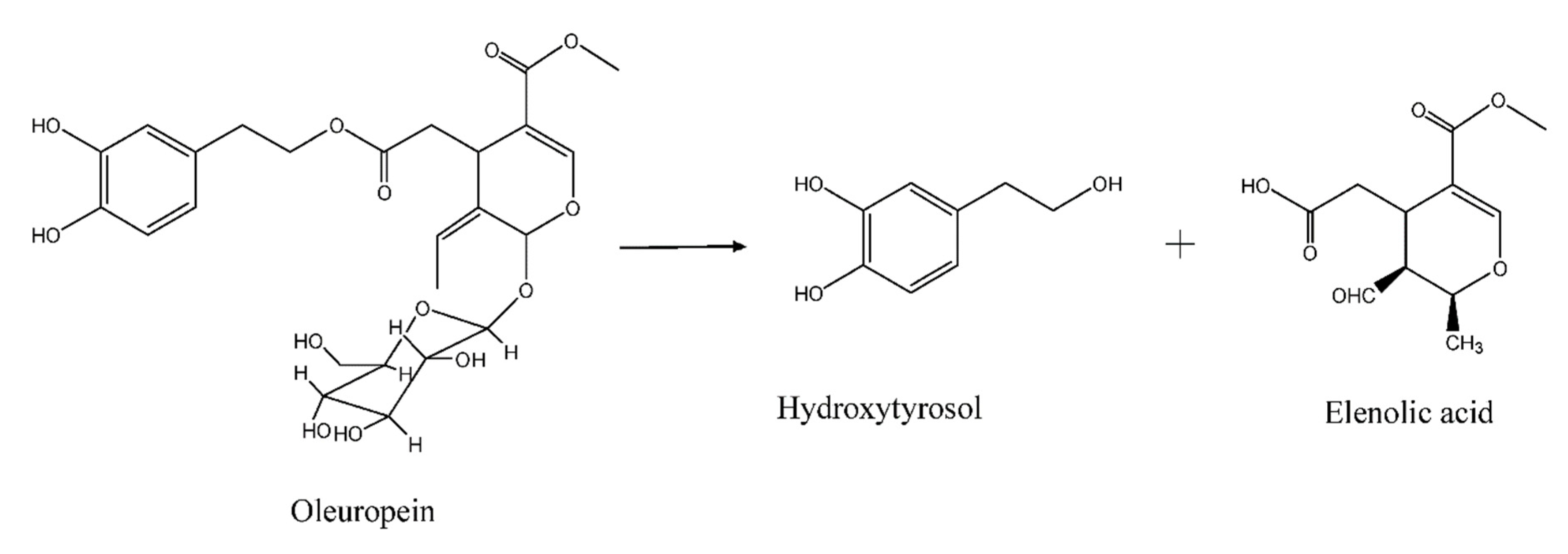

- Briante, R.; Cara, F.L.; Tonziello, M.P.; Febbraio, F.; Nucci, R. Antioxidant Activity of the Main Bioactive Derivatives from Oleuropein Hydrolysis by Hyperthermophilic β-Glycosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem., <bold>2001</bold>, 49, 3198–3203. [CrossRef]

- Odiatou, E.M., Skaltsounis, A.L., Constantinou, A.I. Identification of the factors responsible for the in vitro pro-oxidant and cytotoxic activities of the olive polyphenols oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. Cancer Lett., <bold>2013</bold>, 330, 113–121. [CrossRef]

- Fares, R., Bazzi, S., Baydoun, S.E., Abdel-Massih, R.M. The antioxidant and anti-proliferative activity of the Lebanese <italic>Olea europaea</italic> extract. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr., <bold>2011</bold>, 66, 58–63. [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A., Viggiani, I., Terracone, C., Romaniello, R., Del Nobile, M.A. Physical and sensory properties of bread enriched with phenolic aqueous extracts from vegetable wastes. Czech J. Food Sci., <bold>2016</bold>, 33, 247-253. https://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/redir.pf?u=https%3A%2F%2Fdoi.org%2F10.17221%252F528%252F2014-CJFS;h=repec:caa:jnlcjf:v:33:y:2015:i:3:id:528-2014-cjfs.

- Čukelj, N., Putnik, P., Novotni, D., Ajredini, S., Voučko, B., Duška, Ć. Market potential of lignans and omega-3 functional cookies. Brit Food J., <bold>2016</bold>, 118, 2420 - 2433. [CrossRef]

- Predrag Putnik, Francisco J. Barba, Ivana Španić, Zoran Zorić, Verica Dragović-Uzelac, Danijela Bursać Kovačević. Green Extraction Approach for the Recovery of Polyphenols from Croatian Olive leaves (Olea europea). Food and Bioproducts Processing, 2017, 106, 19-28. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M., Rabii, N.S., Garbaj, A.M., Abolghait, S.K. Antibacterial effect of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves extract in raw peeled undeveined shrimp (<italic>Penaeus semisulcatus</italic>). International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine, <bold>2014</bold>, 2, 53-56. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M., Rabii, N.S., Garbaj, A.M., Abolghait, S.K. Antibacterial effect of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves extract in raw peeled undeveined shrimp (<italic>Penaeus semisulcatus</italic>). International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine, <bold>2014</bold>, 2, 53-56. [CrossRef]

- Karabagias IK, Dimitriou E, Kontakos S, Kontominas MG. Phenolic profile, colour intensity, and radical scavenging activity of Greek unifloral honeys. Eur Food Res Technol., 2016, 242:1201–1210. https:// doi. org/ 10. 1007/ s00217- 015- 2624-6. [CrossRef]

- Vardakas A., Shikov V., Dinkova R., Mihalev K. Valorization of the enzyme-assisted extraction of polyphenols from saffron (<italic>Crocus sativus L.</italic>) tepals. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment, <bold>2021</bold>, 20(3) 2021, 359–367. [CrossRef]

- Kalcheva-Karadzhova, K., Shikov, V., Mihalev, K., Dobrev, G., Ludneva, D., Penov, N. Enzyme-assisted extraction of polyphenols from rose (<italic>Rosa damascene</italic> Mill.) petals. Acta Univ. Cibin. Ser. E: Food Technol., <bold>2014</bold>, 18, 65‒72. [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, L., Kalbasi-Ashtari, A., Hamedi, M., Ghorbani, F. Effects of enzymatic extraction on anthocyanins yield of saffron tepals (Crocos sativus) along with its color properties and structural stability. J. Food Drug Anal., <bold>2015</bold>, 23, 210‒218. [CrossRef]

- Sun T., Tang J., Powers J. Effect of Pectolytic Enzyme Preparations on the Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Asparagus Juice. J. Agric. Food Chem., <bold>2005</bold>, 53, 42-48. [CrossRef]

- Markhali F., Teixeira J., Rocha C. Olive Tree Leaves—A Source of Valuable Active Compounds. Processes, <bold>2020</bold>, 8, 1177. [CrossRef]

- Deng J., Yang H., Capanoglu E., Cao H., Xiao J. Technological aspects and stability of polyphenols. Polyphenols: Properties, Recovery, and Applications, <bold>2018</bold>, Pages 295-323. [CrossRef]

- Volf I., Ignat I., Neamtu M., Popa V. Thermal stability, antioxidant activity, and photo-oxidation of natural polyphenols. Chemical Papers, <bold>2014</bold>, 68(1), 121-129. [CrossRef]

- Mourtzinos I., Anastasopoulou E., Petrou A., Grigorakis S., Makris D., Biliaderis C. Optimization of a green extraction method for the recovery of polyphenols from olive leaf using cyclodextrins and glycerin as co-solvents. J Food Sci Technol (<bold>2016</bold>) 53(11):3939–3947. [CrossRef]

- Silveira da Rosa G., Vanga S., Gariepy Y., Raghavan V. Comparison of microwave, ultrasonic and conventional techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from olive leaves (<italic>Olea europaea</italic> L.). Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, (2019) 58:102234. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Carres, L., Mas-Capdevila, A., Sancho-Pardo, L., Bravo, F. I., Mulero, M., Muguerza, B., Arola-Arnal, A. Optimized extraction by response surface methodology used for the characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds in whole red grapes (<italic>Vitis vinifera</italic>). Nutrients, <bold>2018</bold>, 10(12), 1931. [CrossRef]

- Kalcheva-Karadzhova, K. D., Mihalev, K. M., Ludneva, D. P., Shikov, V. T., Dinkova, R. H., Penov, N. D. Optimizing enzymatic extraction from rose petals (<italic>Rosa damascena</italic> Mill.). Bulg. Chem. Comm., <bold>2016</bold>, 48, 459‒463.

- Chanioti, S., Siamandoura, P. & Tzia, C. Evaluation of Extracts Prepared from Olive Oil By-Products Using Microwave-Assisted Enzymatic Extraction: Effect of Encapsulation on the Stability of Final Products. Waste Biomass Valor., <bold>2016</bold>, 7, 831–842. [CrossRef]

- Erbay Z. and Icier F. Optimization of Drying of Olive Leaves in a Pilot-Scale Heat Pump Dryer. Drying Technology, <bold>2009</bold>, 27:3,416. [CrossRef]

| Yield (%) |

TPPb (mg GAE / L) |

DPPHc (AA %) |

|

| Control (no enzyme) | 64.00 ± 3.20a | 442.13 ± 22.11a | 64.76 ± 3.24a |

| 1 | 62.36 ± 3.12ab | 434.90 ± 21.74a | 66.51 ± 3.33a |

| 2 | 63.18 ± 3.16ac | 387.53 ± 19.38b | 68.36 ± 3.42a |

| 3 | 66.82 ± 3.34a | 377.63 ± 18.88b | 70.48 ± 3.52a |

| Mix 1 | 64.17 ± 3.21a | 447.64 ± 22.38a | 69.05 ± 3.45a |

| Mix 2 | 56.90 ± 2.84b | 465.91 ± 23.30a | 70.32 ± 3.52a |

| Mix 3 | 61.68 ± 3.08ab | 468.19 ± 23.41a | 69.85 ± 3.49a |

| Mix 4,5,6 | 58.19 ± 2.91bc | 464.64 ± 23.23a | 70.08 ± 3.50a |

| No | Coded values | Enzyme dose (%E/Sa) | Time (min) | TPPb (mg GAE/L) | DPPHc (AA%) | Yieldd, (%) | |

| X1 | X2 | Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |||

| 1 | - | - | 0.02 | 30 | 553.99a | 55.23a | 57.13ad |

| 2 | + | - | 0.18 | 30 | 495.11b | 57.22a | 64.98bcg |

| 3 | - | + | 0.02 | 210 | 602.88cd | 58.61a | 57.73ad |

| 4 | + | + | 0.18 | 210 | 572.06ac | 58.33a | 55.54ad |

| 5 | - | 0 | 0.02 | 120 | 530.78ab | 56.85a | 61.05dce |

| 6 | + | 0 | 0.18 | 120 | 582.61ac | 57.78a | 58.22adf |

| 7 | 0 | - | 0.1 | 30 | 605.55c | 57.31a | 70.14g |

| 8 | 0 | + | 0.1 | 210 | 510.42ab | 58.82a | 62.42bef |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 120 | 556.85ad | 58.21a | 65.49bef |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 120 | 557.44ad | 58.22a | 65.72bef |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 120 | 556.95ad | 57.98a | 66.12bef |

| Extraction Method | Total Polyphenol Content | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Assisted Extraction | 605.55 mg GAE / L | current |

| Microwave - Assisted Enzymatic Extraction | 34.53 mg GAE / g | 29 |

| Ethanol 80% | 54.92 mg GAE / g | 24 |

| Cyclodextrins and Glycerin co-solvents | 54.33 mg GAE / g | 27 |

| Microwave- Assisted Extraction | 104.22 mg GAE / g | 28 |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction | 80.52 mg GAE / g | 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).