Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

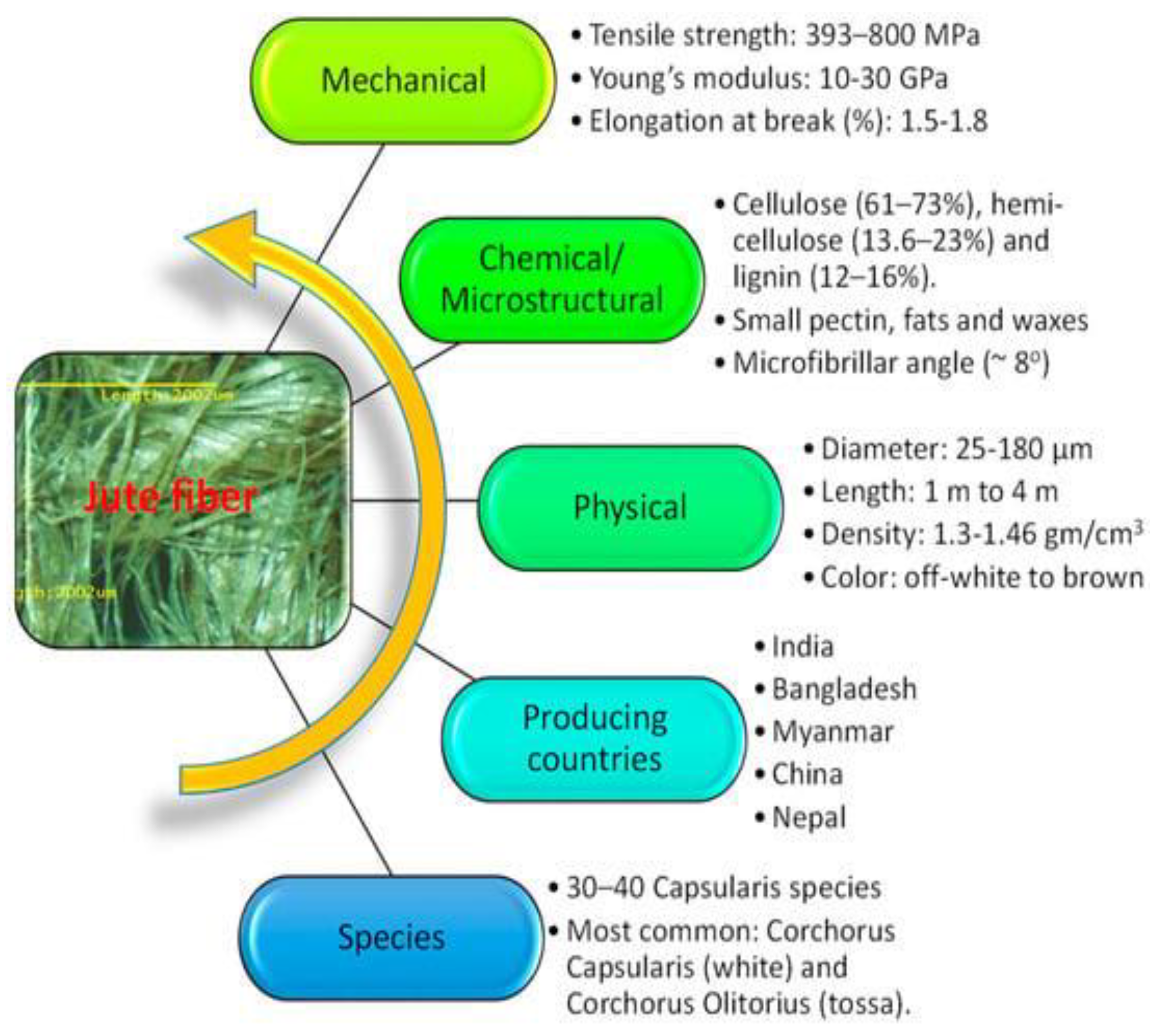

Keywords:

Introduction

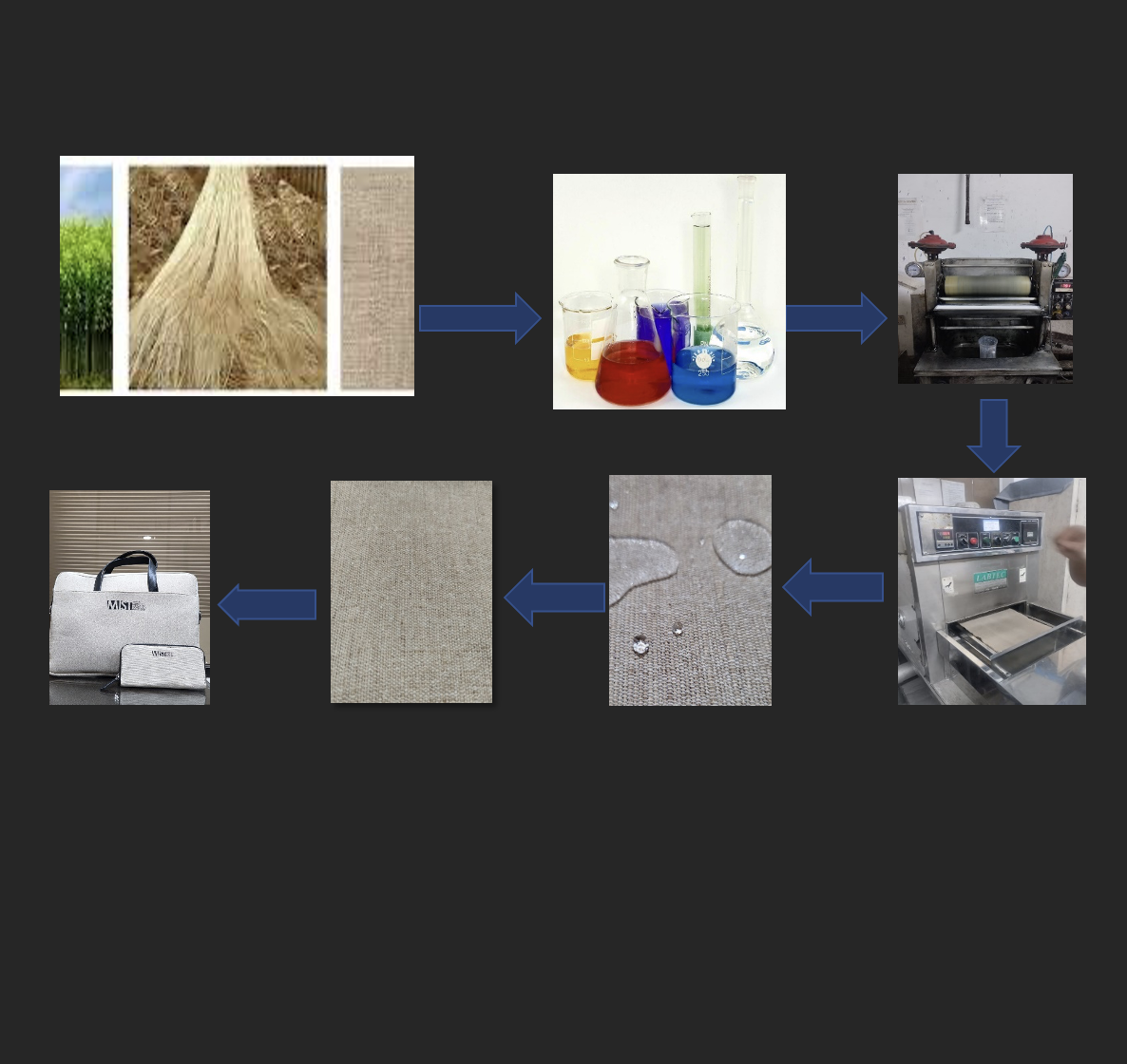

Materials and Methods

Materials

Methods

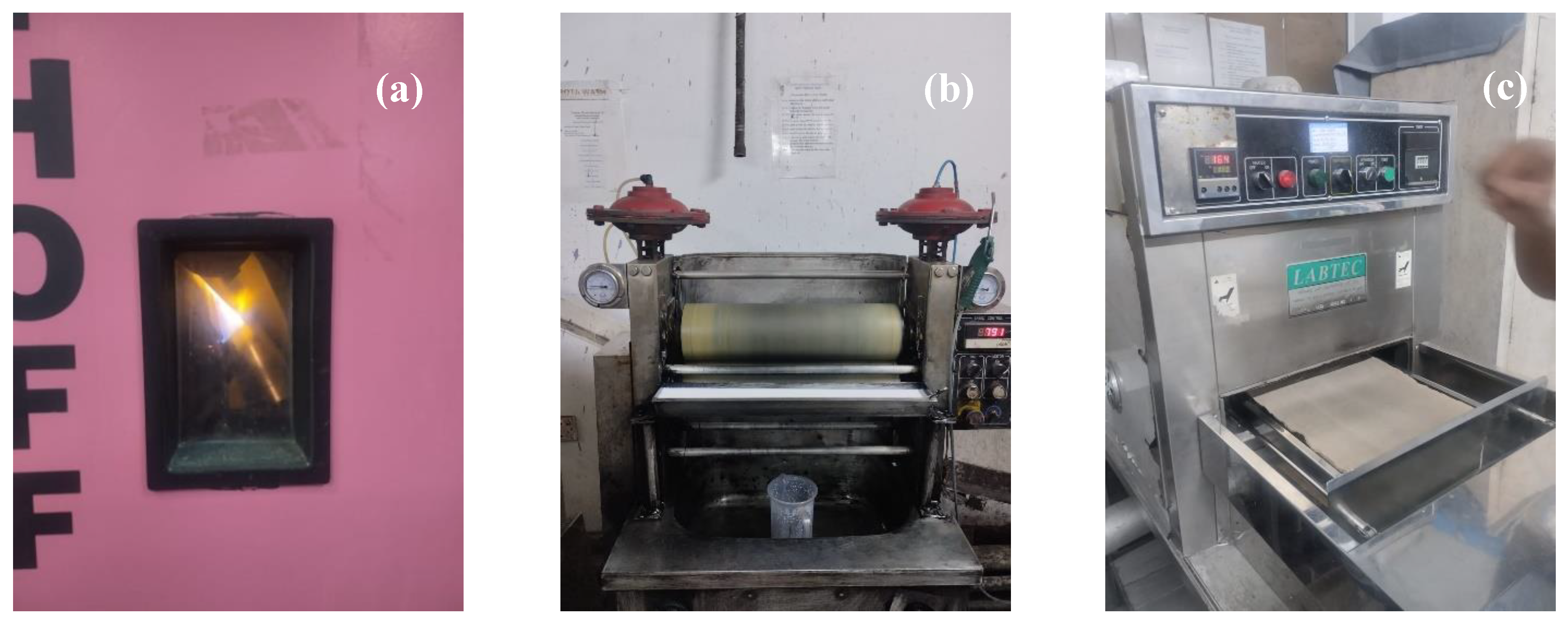

Treatment of the Jute Fabric

Evaluation of Water Repellence

- Spray Rating Test

- Specimen Size: 180 mm × 180 mm (7 in. × 7 in.)

- Conditioning: Minimum 4 hours at 65 ± 2% relative humidity and 21 ± 1°C (70 ± 2°F)

- Water Volume: 250 mL of distilled water at 27 ± 1°C (80 ± 2°F)

- Spray Time: 25–30 seconds

- Apparatus: AATCC Spray Tester

- Assessment: Visual comparison to a standard chart

- ii.

- Drop test

- iii.

- Absorption test

Results and Discussion

Drop Test

Absorption Test

Spray Rating Test

Manufacturing Cost Analysis

| Product name | Price (BDT) | Bio Degradability |

|---|---|---|

| Jute bag | 100 - 800 | Good |

| Canvas bag | 300-1500 | Good |

| Cotton grocery bag | 50-500 | Good |

| Polyester shopping bag | 150-800 | Poor |

| Leather bag | 500-5000 | Good |

| Nylon backpack | 100-5000 | Poor |

| Paper bag | 20-200 | Good |

| Woven straw beach bag | 200-1000 | Good |

| Plastic grocery bag | 20-200 | Worst |

| Water-repellent jute bag | 150-1000 | Good |

Conclusion

Funding

Authors' Contributions

Ethics and consent

Availability of data and material

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Madara, D. S. , Namango, S. S., & Wetaka, C. Consumer-perception on polyethylene-shopping-bags. Journal of Environment and Earth Science 2016, 6, 12–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S. S. , Shaikh, M. N., Khan, M. Y., Alfasane, M. A., Rahman, M. M., & Aziz, M. A. Present status and future prospects of jute in nanotechnology: A review. The Chemical Record 2021, 21, 1631–1665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jahan, A. (2019). The environmental and economic prospects of jute with a connection to social factors for achieving Sustainable Development.

- Ullah, A. , Shahinur, S., & Haniu, H. On the Mechanical Properties and Uncertainties of Jute Yarns. Materials 2017, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M. S. Jute–a versatile natural fiber. Cultivation, extraction, and processing. Industrial applications of natural fibers: structure, properties and technical applications.

- Ullah, A. , Shahinur, S., & Haniu, H. On the Mechanical Properties and Uncertainties of Jute Yarns. Materials 2017, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahinur, S. , Hasan, M., Ahsan, Q., Sultana, N., Ahmed, Z., & Haider, J. Effect of Rot-, Fire-, and Water-Retardant Treatments on Jute Fiber and Their Associated Thermoplastic Composites: A Study by FTIR. Polymers 2021, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaysar, M. A. , Habib, M. M., Shahinur, S., Khan, M. N. I., Jamil, A. T. M. K., & Ahmed, May). Mechanical and thermal properties of jute nano-clay modified polyester bio-composite, in Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Natural Fibers, Online, Portugal (pp. 17–19)., S. J. (2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shahinur, S. , Hasan, M., Ahsan, Q., Sultana, N., Ahmed, Z., & Haider, J. Effect of Rot-, Fire-, and Water-Retardant Treatments on Jute Fiber and Their Associated Thermoplastic Composites: A Study by FTIR. Polymers 2021, 13, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandekar, H. , Chaudhari, V., & Waigaonkar, S. A review of jute fiber reinforced polymer composites. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 26, 2079–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrola-Núñez, H. , Herrera-Franco, P. J., Rodríguez-Félix, D. E., Soto-Valdez, H., & Madera-Santana, T. J. (2018). Surface modification and performance of jute fibers as reinforcement on polymer matrix: an overview. Journal of Natural Fibers. [CrossRef]

- Shahinur, S. , Hasan, M., Ahsan, Q., Saha, D. K., & Islam, M. S. Characterization of the properties of jute fiber at different portions. S. Characterization of the properties of jute fiber at different portions. International Journal of Polymer Science 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A. K. , & Jayachandran, K. Jute fiber for reinforced composites and its prospects. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals Science and Technology. Section A. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals 2000, 353, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, S. , & Balachandran, G. (2008). Structural behavior of jute fiber composites review. [CrossRef]

- Faruk, O. , Bledzki, A. K., Fink, H. P., & Sain, M. Biocomposites reinforced with natural fibers: 2000–2010. Progress in polymer science 2012, 37, 1552–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, S. , Ramakrishna, A., & Kumar, M. S. Comparison of jute and banana fiber composites: A review. International Journal of Current Engineering and Technology 2014, 2, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, D. V. , Srinivas, K., & Naidu, A. L. A review on jute stem fiber and its composites. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol 2017, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H. , Singh, J. I. P., Singh, S., Dhawan, V., & Tiwari, S. K. A brief review of jute fiber and its composites. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 28427–28437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogna, E. , Kumar, R., Anurag, Sahoo, A. K., & Panda, A. A comprehensive review on jute fiber reinforced composites. Advances in industrial and production engineering: select proceedings of FLAME 2019, 2018, 459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M. A. , Zwawi, M., Taqi Mehran, M., Kanthasamy, R., & Bahadar, A. Jute Based Bio and Hybrid Composites and Their Applications. Fibers 2019, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, M. , Islam, T., & Bhuiya, M. Jute Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive review. Int. J. Mech. Prod 2020, 10, 3053–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Sanivada, U. K. , Mármol, G., Brito, F. P., & Fangueiro, R. PLA Composites Reinforced with Flax and Jute Fibers—A Review of Recent Trends, Processing Parameters and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2020, 12, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelar, P. B. , & Narendra Kumar, U. (2021, February). A short review on jute fiber reinforced composites. In Materials Science Forum (Vol. 1019, pp. 32–43). Trans Tech Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Song, H. , Liu, J., He, K., & Ahmad, W. A comprehensive overview of jute fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2021, 15, e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. S. , & Alauddin, M. World production of Jute: A comparative analysis of Bangladesh. International Journal of Management and Business Studies 2012, 2, 014–022. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, V. , & Biswas, S. Physical and mechanical properties of bi-directional jute fiber epoxy composites. Procedia Engineering 2013, 51, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M. S. , & Dastan, T. Impact and flexural properties of hybrid jute/HTPET fiber reinforced epoxy composites. Indian Journal of Fiber & Textile Research (IJFTR) 2017, 42, 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ilman, K. A. , & Hestiawan, H. (2018). The tensile strength evaluation of untreated agel leaf/jute/glass fiber-reinforced hybrid composite. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 288, No. 1, p. 012088). IOP Publishing. DOI 10. 1088. [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi, A. , Jena, H., & Surekha, B. Effect of clams shell in impact properties of jute epoxy composite. Materials Today: Proceedings 2018, 5, 19997–20001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selver, E. , Ucar, N., & Gulmez, T. Effect of stacking sequence on tensile, flexural, and thermomechanical properties of hybrid flax/glass and jute/glass thermoset composites. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2018, 48, 494–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A. K. , Narang, H. K., & Bhattacharya, S. Mechanical properties of natural fiber polymer composites. Journal of Polymer Engineering 2017, 37, 879–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, P. T. R. , & Biswas, S. Influence of fiber surface treatments on physico-mechanical behavior of jute/epoxy composites impregnated with aluminum oxide filler. Journal of Composite Materials 2017, 51, 3909–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devireddy, S. B. R. , & Biswas, S. Physical and mechanical behavior of unidirectional banana/jute fiber reinforced epoxy based hybrid composites. Polymer composites 2017, 38, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, G. , Milioto, S., Parisi, F., & Lazzara, G. Halloysite nanotubes loaded with calcium hydroxide: alkaline fillers for deacidifying waterlogged archeological woods. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2018, 10, 27355–27364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, G. , Danilushkina, A., Evtugyn, V., Lazzara, G., Milioto, S., Parisi, F., Rozhina, E., & Fakhrullin, R. Halloysite Nanotubes: Controlled Access and Release by Smart Gates. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. , Wang, Q., Xia, Z., Yu, J., & Cheng, L. Mechanical modification of degummed jute fiber for high-value textile end uses. Industrial Crops and Products 2010, 31, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilfi KF, A. , Balan, A., Bin, H., Xian, G., & Thomas, S. Effect of surface modification of jute fiber on the mechanical properties and durability of Jute fiber-reinforced epoxy composites. Polymer Composites 2018, 39, E2519–E2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, K. , Sarikanat, M., Seki, Y., Erkan, G., Erdoğan, Ü. H., & Erden, S. Surface treatments of jute fabric: The influence of surface characteristics on jute fabrics and mechanical properties of jute/polyester composites. Industrial Crops and Products 2012, 35, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandekar, H. , Chaudhari, V., & Waigaonkar, S. A review of jute fiber reinforced polymer composites. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 26, 2079–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M. K. , Srivastava, R. K., & Bisaria, H. The potential of jute fiber reinforced polymer composites: A review. Int. J. Fiber Text. Res 2015, 5, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S. S. , Shaikh, M. N., Khan, M. Y., Alfasane, M. A., Rahman, M. M., & Aziz, M. A. Present status and prospects of Jute in nanotechnology: A review. The Chemical Record 2021, 21, 1631–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Thang, Silane/Siloxane emulsions for masonry surfaces., Patent application PCT/AU94/00767 (https://patents.google.com/patent/WO1995016752A1/en.

- Ssegawa, J. K. , & Muzinda, M. Feasibility assessment framework (FAF): A systematic and objective approach for assessing the viability of a project. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 181, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raw materials | Quantity | Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| NUVA N2114 | 100 gm/L, 120 gm/L, 140 gm/L |

|

| Acetic acid | 0.5-1 gm/L | |

| Arkophob DAN | 10 gm/L |

| Rating | ISO Equivalent | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | ISO 5 | No sticking or wetting of the specimen face |

| 90 | ISO 4 | Slight random sticking or wetting of the specimen face |

| 80 | ISO 3 | Wetting of the specimen face at spray points |

| 70 | ISO 2 | Partial wetting of the specimen face beyond spray points |

| 50 | ISO 1 | Complete wetting of the entire specimen face beyond spray points |

| 0 | – | Complete wetting of the entire face of the specimen |

| Sample No. | Concentration (g/L) | Chemical | Spray Rating (155°C) | Spray Rating (165°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 100 | Nuva N2114 | 80 | 80 |

| 02 | 120 | Nuva N2114 | 90 | 90 |

| 03 | 140 | Nuva N2114 | 100 | 100 |

| Item | Low GSM Fabric | High GSM Fabric |

|---|---|---|

| Pieces/Yard | 1000 pcs / 500 yards | 1000 pcs / 500 yards |

| Swing | 600 BDT (per pcs) | 600 BDT (per pcs) |

| Fabric Cost | 65 BDT (per pcs) | 150 BDT (per pcs) |

| Treatment Cost | 100 BDT (per pcs) | 100 BDT (per pcs) |

| Transport Cost | 30 BDT (per pcs) | 30 BDT (per pcs) |

| Profit | 100 BDT (per pcs) | 100 BDT (per pcs) |

| Total Cost | 900 BDT (per pcs) | 980 BDT (per pcs) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).