1. Introduction

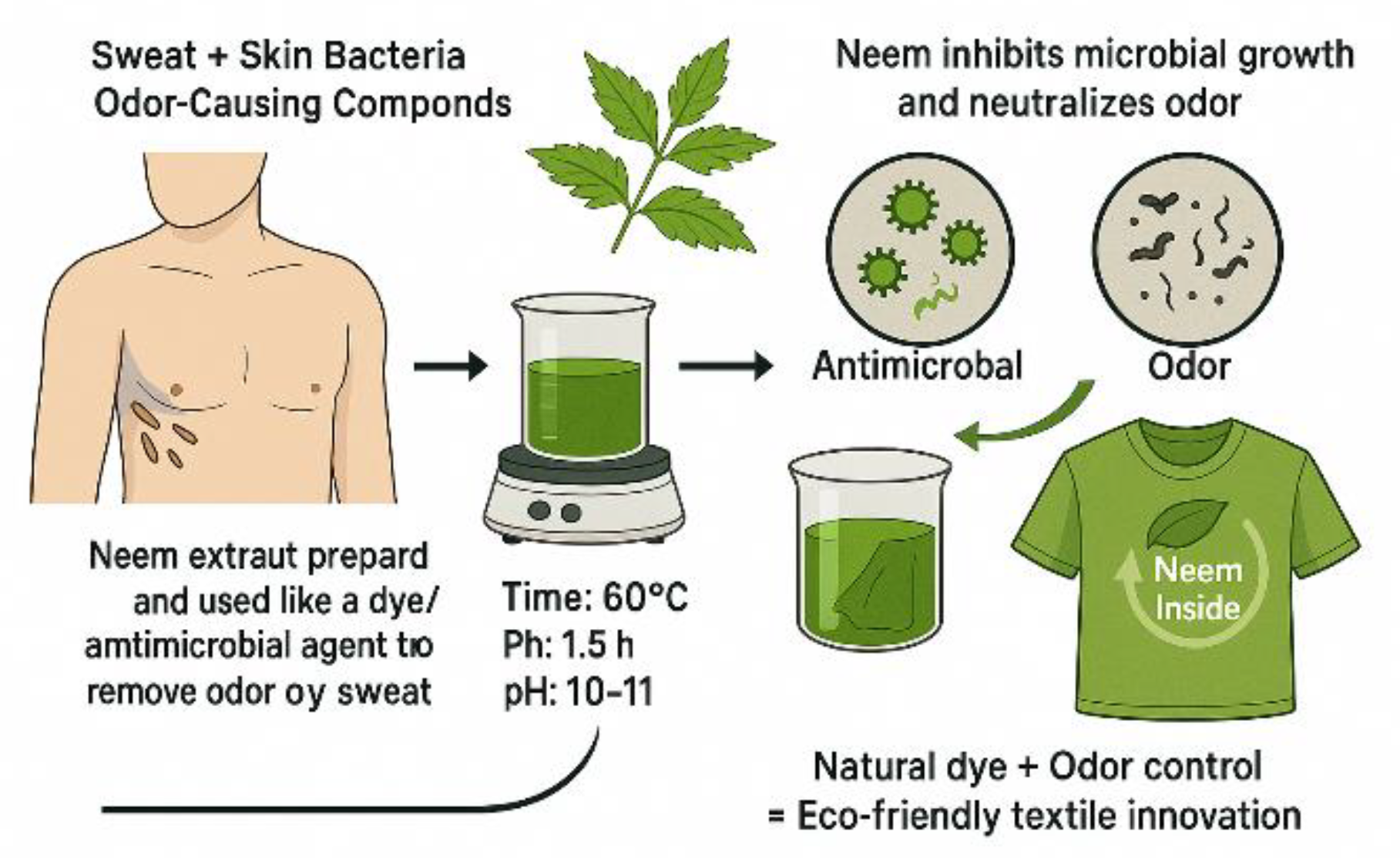

The cloth assiduity is in a transition that seeks to adopted more strategies that promote sustainability and reduce impact on the environment. One area that is of particular interest is the development of green dyes and finishes which enhance aesthetic appearance of fabrics, but also provide some benefits like antimicrobial properties and odor control. Out of the diverse natural materials available, neem (Azadirachta indica) has the potential to be a popular choice owing to its antibacterial properties and phytochemicals (Seth, Khan, & Jana, 2021; Shirvan, Hemmatinejad, Bahrami, & Bashari, 2021, pp. 311S–335S).

Traditionally, neem has been also used in many of the societies as a medicinal herb that has powerful antibacterial activities and skin health effects. Some active compounds are found in the neem tree such as azadirachtin, nimbidin, and various flavonoids exhibit strong antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties (Ajayan & Hebsur, 2020; Hooda, 2021). These properties augment the neem extract as an attractive alternative for use in textile applications, in particular those made from garments that are typical odor causing and are a result of sweat and microbial activity. By adding neem extract to fabric dyeing processes, it not only serves as a natural substitute for synthetic colorants but further enhances the functional effectiveness of the fabric. Findings show that odor- causing bacteria can successfully be controlled using fabrics treated with neem excerpt thus improving the hygiene & durability of clothes (Fabric, 2013; Koli, Rohtela, & Meena, 2022). For example, there are studies which have established the fact that neem excerpt can be used effectively in areas looking to combat bacterial counts through infusion in fabrics making them ideal for activewear and other clothing specifics such as washables (Oyekanmi et al., 2021; Surendra, Gagan, Soundarya, & Naresh, 2020, p. 100017).

Equally important, the incorporation of neem extract for textile purposes addresses the increasing consumer demand for sustainable and eco-friendly products. The advancing knowledge of the negative impacts of synthetic dyes and chemical finishes makes it certain that the textile sector will have to look for natural products that are efficient and safe for human beings and the ecosystem (Ikhioya, Nkele, & Ochai-Ejeh, 2023, pp. 214–220; Putsakum, Lee, Suthiluk, & Rawdkuen, 2018, pp. 611–620). Provided neem extract can function as a dye in addition to an antimicrobial agent, it would become an increasingly significant raw material in the quest for new textile designs.

The aim of this work is to investigate if the neem extract can turn into a natural dye and also an antimicrobial agent in apparels. Thus, it will be a wonder product for all studying the link between fashion and sustainability, and also one of its many properties could be used to study all aspects of technology that are eco-friendly. These products are made in response to the growing demand for eco-friendly textiles in today’s market.

Since ancient times, dyes were originally produced by plants, insects, and minerals; therefore, the use of natural dyes has been a common practice in dyeing textiles for centuries. For instance, natural dyes have been used to create such distinctive dyes as indigo, madder, and cochineal, which boast their natural colors and cultural significance in various parts of the world (Chauhan, Parekh, & Solanki, 2023, pp. 1–2). But when the 19th century brought the discovery of synthesized dyes, the completely changed industry introduced not only wider color gamut and fastness but also economic aspects. Although, synthetic dyes pose additional problems due to their non-biodegradable nature, causing high-toxicity effluent discharge both at the time of manufacture and during application also,(Chauhan, Parekh, & Solanki, 2023, pp. 1–2). Most recently, development of dyeing processes has recently received considerable interest in the use of natural dyes as textile mills recently search for sustainable products and so-called ecofriendly products as presented by (Chauhan et al., 2023, pp. 1–2).

Other literature also presents the result of recent research that was conducted into the possibility of mordant dyes in place of synthetic dyes. Mordant dyes, which involve a mordant in order to make the dye fix to the fabric, improve the color fastness in natural dyes as per (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p.1). Ding and Freeman (2017) explored the optimization of mordant dye application on cotton, demonstrating that shades comparable to those produced by natural dyes can be achieved using specific mordant dyes following pretreatments with iron and aluminum salts (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 1). Their findings indicated that the combination of mordant and natural dyes could extend the color gamut in textile applications without losing the ecological advantages of natural dyeing. (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 1)

On the other hand, Chauhan et al. (2023) have reviewed historical uses and sources of natural dyes and emphasized the need for sustainable practices in the dyeing industry (Chauhan et al., 2023, pp. 1–2). They pointed out that natural dyes not only provide aesthetic appeal but also contribute to environmental conservation by reducing reliance on synthetic alternatives (Chauhan et al., 2023, pp. 1–2). The integration of natural dyes with mordanting techniques is an innovative approach to textile dyeing, meeting the modern demands of sustainability and eco-friendliness. This is supported by (Chauhan et al., 2023, p. 1) and (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 1).

The following research work is based on the application of different natural and mordant dyes on cotton fabrics to study their color fastness properties and overall dyeing performance. The study of the interaction of natural and mordant dyes can perhaps help in evolving processes for sustainable dyeing that would respect traditional techniques but answer the call of modern environmental concerns.

2. Related Work

Body odor management, especially auxiliary body odor, has been the focus of recent research on account of its social issues and shortcomings of conventional deodorants. Recent studies explored the potential of natural alternatives to combat microbial causes of body odor, with particular focus on medicinal plant extracts.

2.1. Antimicrobial Properties of Medicinal Plants Like Neem

In a recently conducted broad study, (Athirah et al., 2021) assessed the antimicrobial activities of ten medicinal plant extracts against axillary microbiota responsible for body odor: Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum, and Corynebacterium jeikeium. The authors determined that the ethanol extracts exhibited various levels of antibacterial action with MIC values ranging from 1.563 to 0.098 mg/mL using the agar well diffusion and microbroth dilution techniques. Notably, extracts from Piper betle, Syzygium aromaticum, and Curcuma xanthorrhiza demonstrated the most potent antibacterial effects, indicating their potential as active ingredients in natural deodorants (Athirah et al.,2021,p.1). In a complementary study, (Sidek et al., 2021) evaluated the antimicrobial potential of ten medicinal plant extracts against skin microbiota responsible for body odor. Their findings were that Piper betle, Curcuma xanthorrhiza, and Syzygium aromaticum extracts had presented significant activities against Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum, and Corynebacterium jeikeium. The present study represents an illustration of the useful contribution of natural extracts in a more effective formulation of deodorants and antiperspirants, which is a safer alternative than using conventional products with hazardous chemicals (Sidek et al., 2021, pp. 1, 4).

2.2. Odor Control Technologies in Textiles

This was supported by several research studies, such as the review by (McQueen & Vaezafshar, 2019), who provided an overview of the various methods of odor evaluation in textiles and fabric characteristics, together with a review of various odor-controlling technologies. Such reviews have pointed out that the origins of textile odor are very diverse, including microbial growth on fabrics, hence underlining an imperative necessity for effective control over textile odor. (McQueen & Vaezafshar, 2019, p. 1). The authors indicated that conventional washing methods seldom remove stubborn odors from fabrics, and thus, textiles should be designed to naturally prevent the development of odor (McQueen & Vaezafshar, 2019, pp. 1–2).

2.3. Environmentally Friendly Methods for Textile Finishing

Other than antimicrobial finishing treatments, environmentally friendly surface modification methods have also been developed, which can improve dyeing properties and confer antimicrobial activity on textiles. Singh et al. (2021) discussed various methods that improve the dyeing process and give an antimicrobial finish, such as plasma treatment and enzyme application. Such approaches are not only improving aesthetic aspects but also functional performance; hence, they are suitable for activewear and other odor-sensitive products (Singh et al., 2021, pp. 1, 3).

2.4. Implications for Sustainable Practices

This growing consumer awareness of health and environmental problems related to synthetic chemicals is a facilitating trend toward natural and sustainable alternative options in the personal care industry as well as textiles. Overall, the research evidence obtained, reviews conducted separately, support the acceptability of using plant extractations combined with clean technology methods within product formulation processes. This not only increases the functionality of textiles but also meets the increasing demand for sustainability in the textile industry. (Athirah et al., 2021; McQueen & Vaezafshar, 2019; Singh et al., 2021)

It has been established that research on the antimicrobial properties of medicinal plants and new methods of textile finishing provides promising pathways to efficient development of natural products for body odor management. Further studies are needed on practical ways such findings could be used to produce effective, yet safe, commercial products.

2.5. Natural Dyes and Effects

In recent years, natural antimicrobial agents have attracted the interest of many industries including textiles and personal care. Karolia & Khaitan (2012) did a study on some natural dyes’ antibacterial properties against cotton fabrics. Among them, neem leaves, turmeric, pomegranate rind, tea leaves, and myrobalan were tested, and the result showed neem leaves were most effective against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, followed by pomegranate rind and turmeric. It is reiterated from the research that these natural dyes have tremendous potential, serving not only aesthetic purposes but also increasing functionality in terms of giving textiles antimicrobial properties. (Karolia & Khaitan, pp. 1-2,10).

Increased environmental concern due to synthetic dyes is one of the major causes for revived interest in the use of natural dyes in textiles. Chauhan et al. (2023) have presented a review on natural dyeing of textiles, covering historical background and sources of natural dyes, including plants, minerals, and insects. They highlight the ecological benefits of natural dyes, including biodegradability and lower toxicity, unlike the synthetic ones, which have been responsible for considerable water pollution and have had negative impacts on biodiversity (Chauhan et al., 2023, pp. 1–2).

2.6. Mordanting for Natural Dyes

Mordant dyes have been applied on cotton in a number of works with the goal of optimizing dyeing processes and improving color fastness. For instance, Ding and Freeman (2017) investigated the application of mordant dyes along with natural dyes. They showed that colors similar to natural dyes can be obtained on cotton by applying specific mordant pre-treatments (Ding & Freeman, 2017, pp. 1,6). The study focused on a two-step, two-bath approach to enhance dye uptake and depth of color (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 6).

It was also revealed that the history of natural dyes is fraught with a lack of availability and inefficient processes for production, so a need to reorient attention towards synthetics was felt (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 1). As highlighted by Ding and Freeman in their work, even though natural dyes have enjoyed the favor of the public throughout history, the incorporation of mordant dyes into natural dyes would reduce such challenges as color fastness and uneven dyeing (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 1,7).

In addition, some studies have established that mordanting with eco-friendly mordants, such as aluminum and iron salts, enhances the bonding of dyes with cotton fibers, thereby enhancing the dyeing process (Ding & Freeman, 2017, p. 1,5). That agrees with the findings by Ding and Freeman, where they stated that dye fixation might be further enhanced by application of tannic acid together with mordanting (Ding & Freeman, 2017, pp. 5,7).

3. Methodology

3.1. Odor Formation Technique by Sweat

The formation of body odor from sweat is essentially a product of the metabolic activity of skin-resident bacteria, especially in the axillary region. In itself, sweat is odorless when secreted from the apocrine glands. However, once in contact with skin microbiota, the bacteria such as Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus start to metabolize the components of sweat, giving rise to volatile organic compounds responsible for body odor (Gill et al., 2014; James, Austin, Cox, & Taylor, 2004, pp. 787–793).

The major odoriferous compounds generated in this process are short-chain fatty acids and sulfur-containing compounds, such as 3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol (3M3T) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylhexanoic acid (HMHA) (James et al., 2004, pp. 787–793; Troccaz et al., 2008, pp. 203–210). Such bacteria and their activities depend on the individual skin microbiota composition, hygiene practices, and environmental conditions (Gill et al., 2014; James et al., 2004, pp. 787–793).

3.2. Recipe of Dyeing with Neem

| Neem extract: |

15 mL |

| Mordant - Al2(SO4)3: |

5% OWF (On the Weight of Fabric) |

| Glauber salt: |

50 g/L |

| Soda ash: |

25 g/L |

| Levelling agent: |

1.5 ml/L |

| Wetting agent: |

1.5 ml/L |

| Sequestering agent: |

1.5 ml/L |

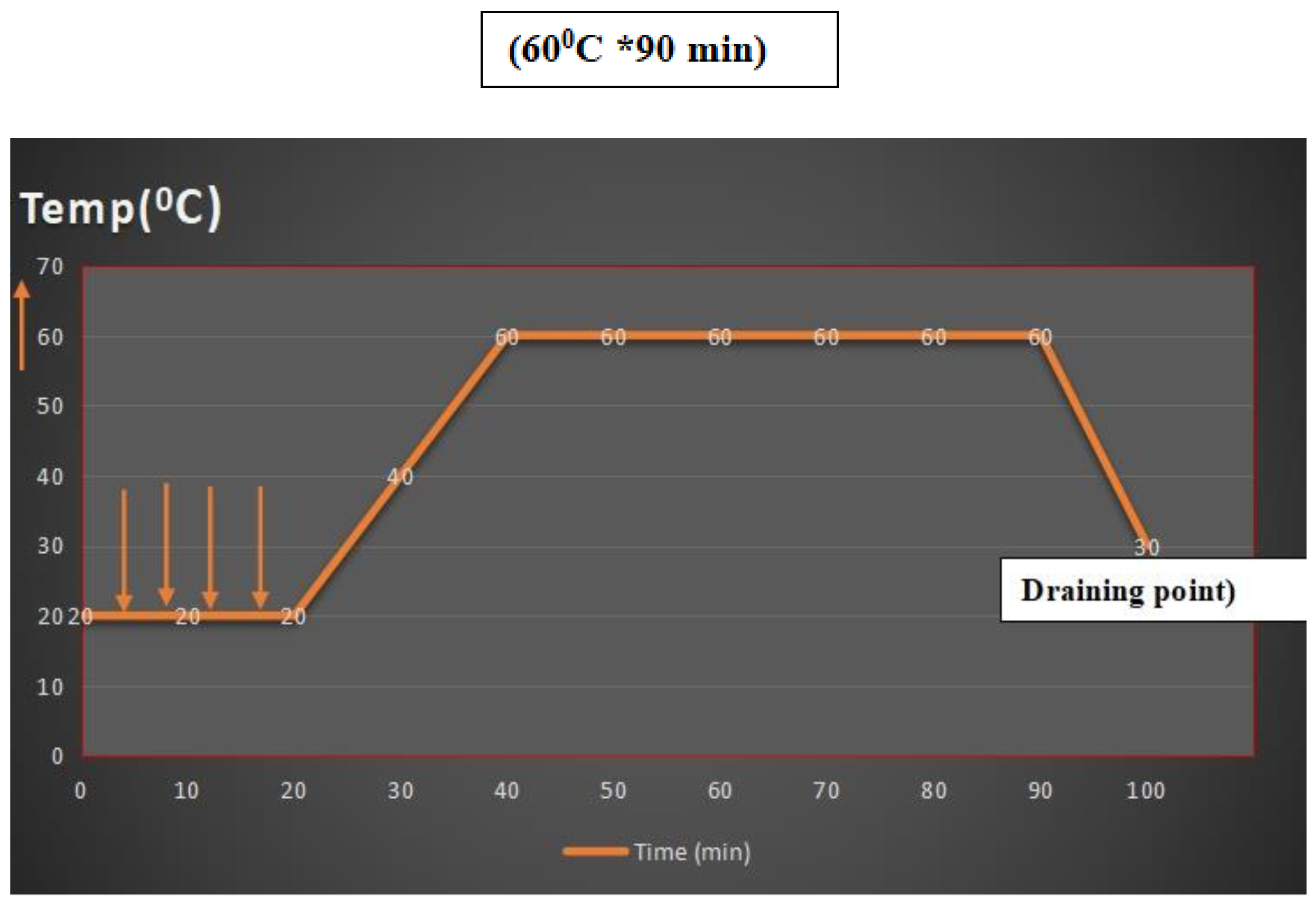

| Temperature: |

60 °C |

| Time: |

1.5 hours |

| PH: |

10 ~ 11 |

| M:L: |

1:20 |

| Fabric weight: |

10 gm |

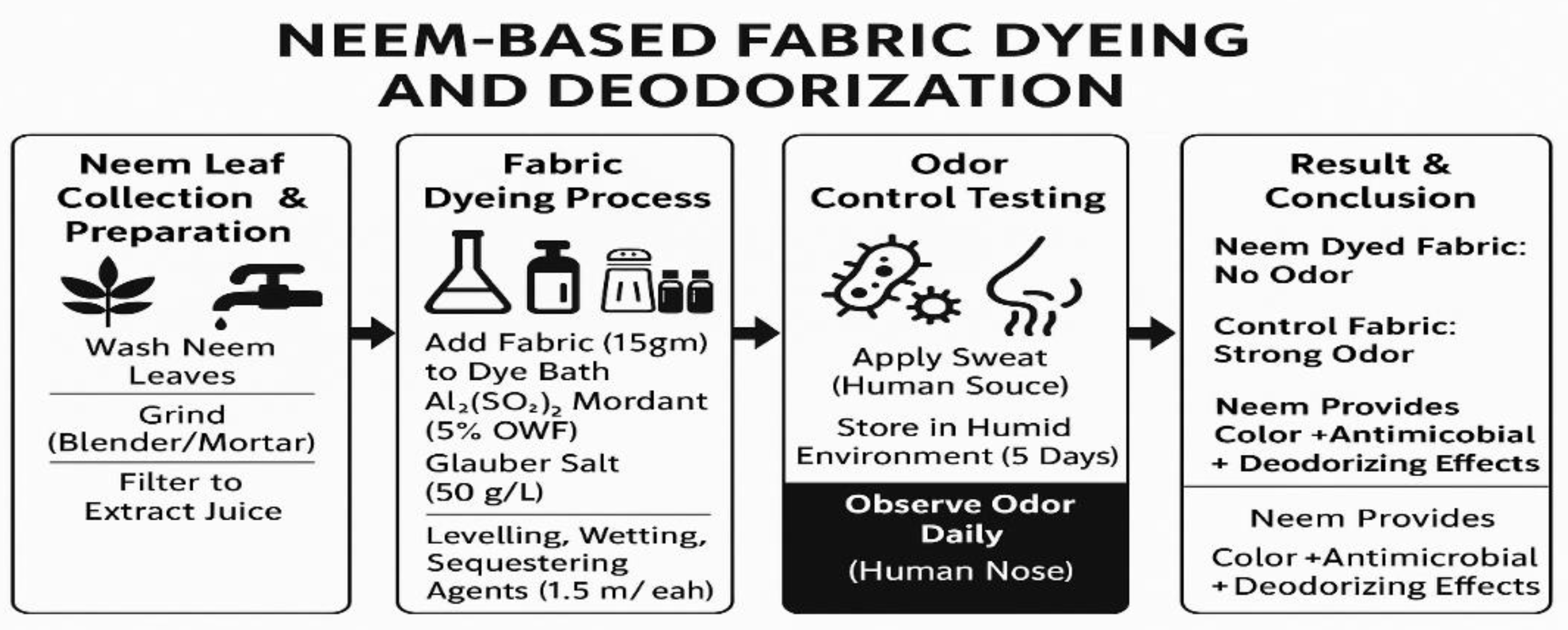

3.3. Preparation of Neem Extract

- ➢

At first, we collected the neem leaf and washed thoroughly with water to remove any impurities.

- ➢

Then we blend it by using an electric blender and wooden mortar.

- ➢

After that, the paste is filtered.

3.4. Procedure of Dyeing with Neem

- ➢

At first, we measured all the required elements in the recipe.

- ➢

Next, we need to prepare a solution and pour it into a tin pot. Shake the solution properly.

- ➢

After that, we need to add the sample fabric and mix well.

- ➢

Next, we placed the pot on a tripod and started heating it using a machine.

- ➢

We must keep the temperature at 600 C and continue the cooking process for 90 minutes.

- ➢

After 90 minutes, we need to wash the sample fabric properly and dry it. Then iron the sample.

3.4.1. Adjusting pH

Measure the pH of the dye bath. If the pH is lower than required, add more soda ash in small increments until the PH is within the desired range.

3.5. Pre-Cautions

- ➢

All chemicals should be measured properly.

- ➢

You must maintain the time and temperature correctly.

- ➢

Shake the solution thoroughly to ensure the chemicals are well mixed; otherwise, it will result in an uneven dye shade.

- ➢

All recipes should be calculated properly.

3.6. Limitation

- ➢

Its effectiveness is temporary and does not provide long-lasting sweat odor control.

- ➢

The level of odor control depends on the dyeing process, fabric types, interactions with materials, etc.

- ➢

All of the fabrics are not suitable for sweat odor control.

- ➢

The conditions of washing have an impact on its efficacy.

4. Results and Discussion

As shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, dyeing with neem leaves changed the fabric used in the experiment from gray to olive green, and the smell of neem is coming from the fabric. Then a sufficient amount of perspiration is applied to both the dyed olive green color fabric and the normal scoured/bleached fabric. Both fabrics were then kept in a humid environment for five days and reviewed. Gradually, it can be seen that the smell of perspiration is gradually increasing from the normal gray fabric; on the other hand, the smell of neem is gradually decreasing from the olive green color fabric, and no sweat smell is found.

As shown in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, the research ends by stating that cloth or fabric colored with neem does not give out any smell of sweat, because of the antimicrobial properties of neem. And also which country takes more benefits from functional clothes.

Fabrics treated with neem have remarkable ability to resist the invasion of microbes preventing the odor cause by sweat. Due to the economic and environmental benefits, neem can not only be used as a fabric dye but its antibacterial and anti-odor attributes make neem a great choice in promoting green textiles. The studies suggest that neem dyed fabric may lead to the development of new fabrics using natural substances that could be used to prevent odours of sweat in the fabric.

- ➢

Color obtained in Fabric: Olive Green

- ➢

Sample Fabric (Neem dyed): No bad odor caused by sweat.

- ➢

Sample Fabric (Without Neem dyeing): Very bad odor caused by sweat.

- ➢

Medicinal Benefit: Reduces the possibilities of bacterial infections on skin/body

5. Conclusions

We know the role of neem leaves in our daily life. Similarly, it’s role in our textiles is immense. First, neem leaves are anti-fungal and anti-bacterial. If we want, we can use this neem leaf to take the textile sector much further. Basically, we can use this neem leaf to remove bad smell created by sweat. We worked on it and got good results from it. It mainly works against fungi and bacteria. When we sweat, salt water is released from our body. The salt water reacts with fungi and bacteria to produce a foul smell. As a result of this smell, we feel uneasy to mix with people. As a result we are deprived of many things. So we can say if we can increase the use of this neem leaf in our industry, then we can get rid of this problem. In the industry, it can be used in various ways, one of which is when we can take a coating of neem leaf juice while doing fabric dyeing. Due to which bacteria, fungus cannot have any effect on that cloth, as a result no bad smell will be created. So we say if we can increase the use of this neem leaf, then we can get rid of this problem.

Basically there is no smell of sweat. But when sweat comes to the contact of body bacteria of skin or garments, then bacteria start decomposes the sweat and makes bad odor. Neem is an antimicrobial agent. So, any kind of treatment with neem (below 60° temperature) kills the body bacteria and prevents bad odor caused by sweat.

References

- Ajayan, A. S., & Hebsur, N. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using neem (Azadirachta indica) and tulasi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) leaf extract and their characterization. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences 2020, 9(12), 2301–2310.

- Athirah, N., Sidek, M., Van Der Berg, B., Husain, K., & Said, M. M. Antimicrobial potential of ten medicinal plant extracts against axillary microbiota causing body odor. Pharmacophore 2021, 12(6), 1–5.

- Chauhan, J., Parekh, S., & Solanki, H. A. Natural textile dyeing: A review. InfoKara 2023, 9(6), 1–13. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372514203.

- Ding, Y., & Freeman, H. S. Mordant dye application on cotton: Optimisation and combination with natural dyes. Coloration Technology 2017, 133(1), 1–10.

- Fabric, W. K. Application of herbal finish to alkali treated polyester cotton. Journal of Herbal Textile Research 2013, 5(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, L., Williams, M. I., & Hamzavi, I. Update on hidradenitis suppurativa: Connecting the tracts. F1000Prime Reports 2014, 6, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hooda, D. S. Application of textile finishing using neem extract: A move towards sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Textiles 2021, 4(2), 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ikhioya, I. L., Nkele, A. C., & Ochai-Ejeh, F. U. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles using neem leaf extract (Azadirachta indica) for energy storage applications. Materials Research Innovations 2023, 28(3), 214–220.

- James, A., Casey, J., Hyliands, D., & Mycock, G. Fatty acid metabolism by cutaneous bacteria and its role in axillary malodour. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2004, 20(8), 787–793. [CrossRef]

- Karolia, A., & Khaitan, U. Antibacterial properties of natural dyes on cotton fabrics. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 2012, 16(2), 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Koli, K., Rohtela, K., & Meena, D. Comparative study and analysis of structural and optical properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles using neem and mint extract prepared by green synthesis method. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2022, 1248(1), 012079.

- McQueen, R. H., & Vaezafshar, S. Odor in textiles: A review of evaluation methods, fabric characteristics, and odor control technologies. Textile Research Journal 2019, 89(12), 1–17.

- Oyekanmi, A., Kumar, U., Syafiq, A. H. P., Olaiya, N. G., Amirul, A., Rahman, A. A., Nuryawan, A., Abdullah, C., & Rizal, S. Functional properties of antimicrobial neem leaves extract-based macroalgae biofilms for potential use as active dry packaging applications. Polymers 2021, 13(2), 124. [CrossRef]

- Putsakum, G., Lee, D., Suthiluk, P., & Rawdkuen, S. The properties of gelatin film–neem extract and its effectiveness for preserving minced beef. Packaging Technology and Science 2018, 31(9), 611–620.

- Rohani Shirvan, A., Hemmatinejad, N., Bahrami, S., & Bashari, A. A comparison between solvent casting and electrospinning methods for the fabrication of neem extract-containing buccal films. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2021, 51 (1_suppl), 311S–335S.

- Seth, M., Khan, H., & Jana, S. Antimicrobial activity study of Ag-ZnO nanoflowers synthesised from neem extract and application in cotton textiles. International Journal of Nanotechnology 2021, 18(1–2), 96–106.

- Sidek, N. A. M., Van Der Berg, B., Husain, K., & Said, M. M. Antimicrobial potential of ten medicinal plant extracts against axillary microbiota causing body odor. Pharmacophore 2021, 12(6), 1–5.

- Singh, M., Vajpayee, M., & Ledwani, L. Eco-friendly surface modification of natural fibres to improve dye uptake using natural dyes and application of natural dyes in fabric finishing: A review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 43, 2868–2871.

- Surendra, B., Gagan, R., Soundarya, G., & Naresh. Thermal barrier and photocatalytic properties of La₂Zr₂O₇ NPs synthesized by a neem extract-assisted combustion method. Journal of Advanced Materials Science 2020, 1(1), 100017.

- Troccaz, M., Borchard, G., Vuilleumier, C., & Starkenmann, C. Gender-specific differences between the concentrations of nonvolatile (R)/(S)-3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol and (R)/(S)-3-hydroxy-3-methyl-hexanoic acid odor precursors in axillary secretions. Chemical Senses 2008, 34(3), 203–210.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).