Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Background

Goals and Hypotheses of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

- Protocol approvals and patient consents

2.3. Tools (for a Detailed Description, Please See Supplementary Material)

2.4. Neuroimaging: Brain Perfusion SPECT Scans

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

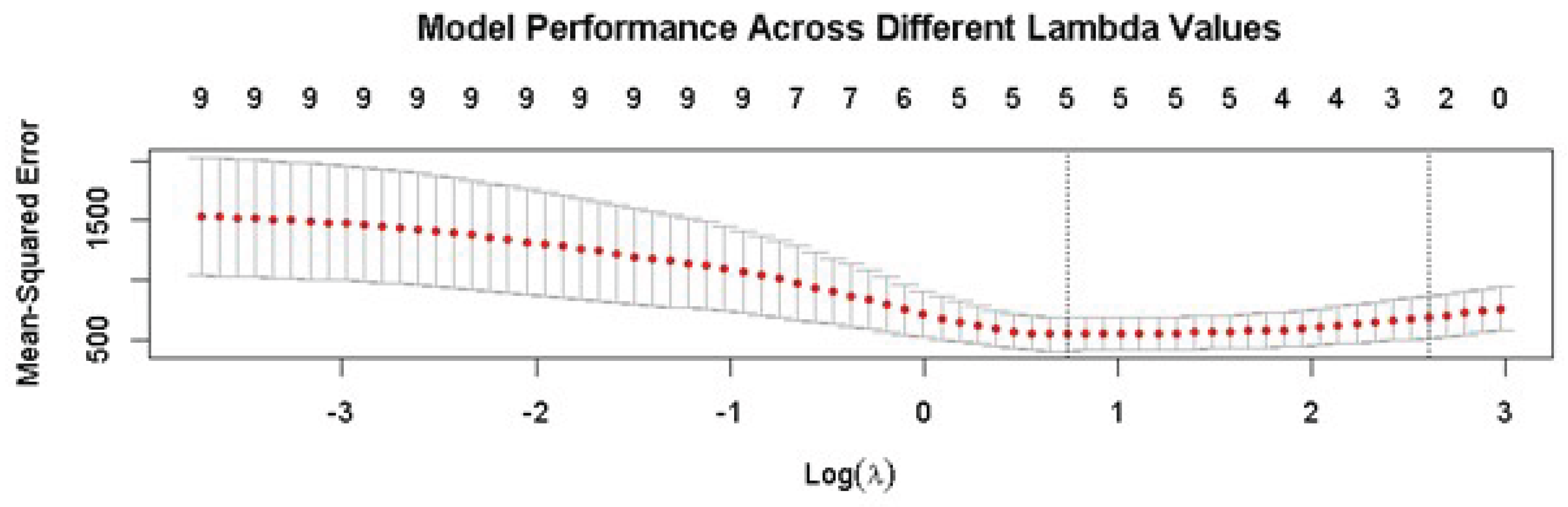

Selection of Variables for Inclusion in the Penalized LASSO Regression Analysis

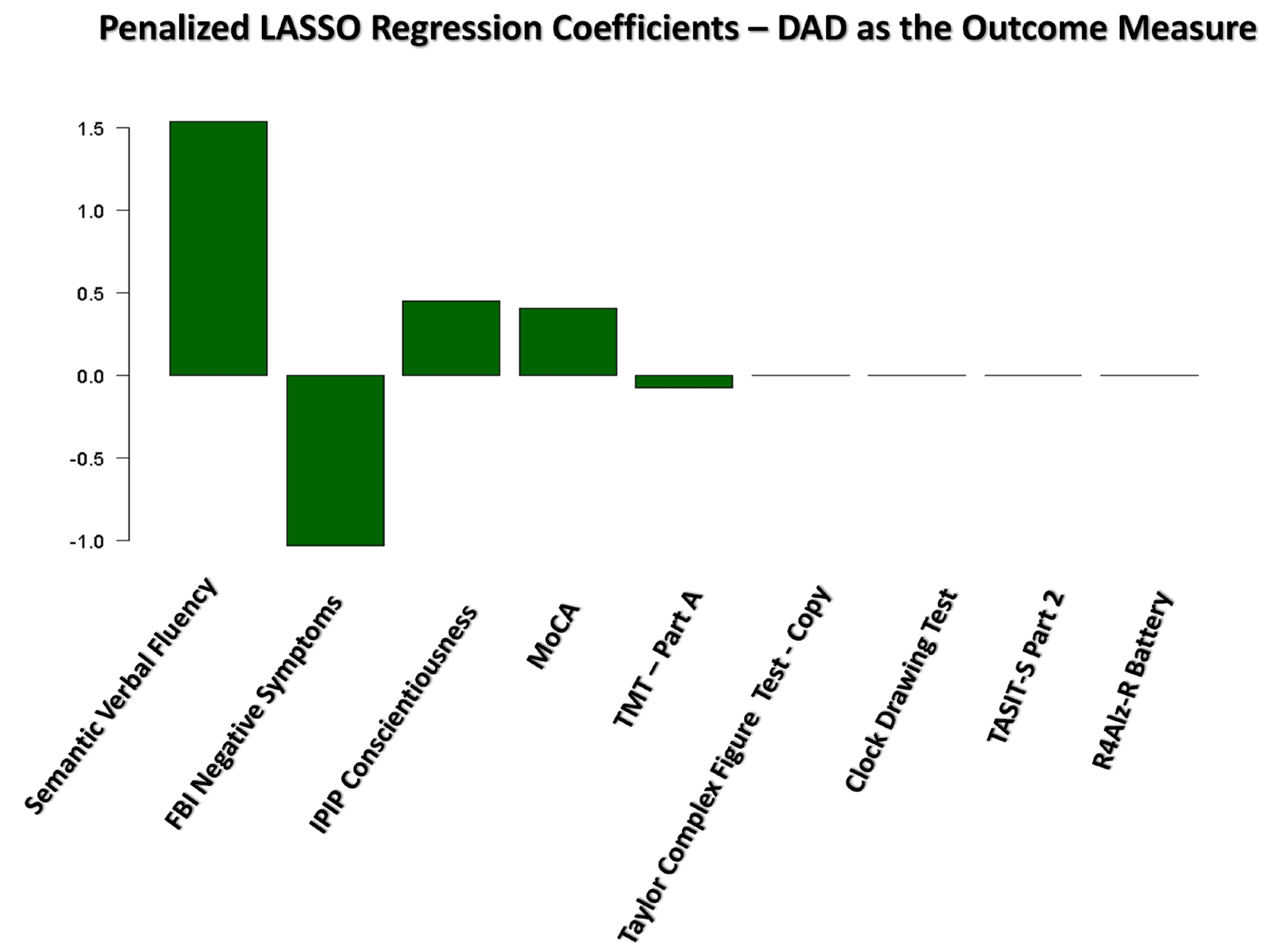

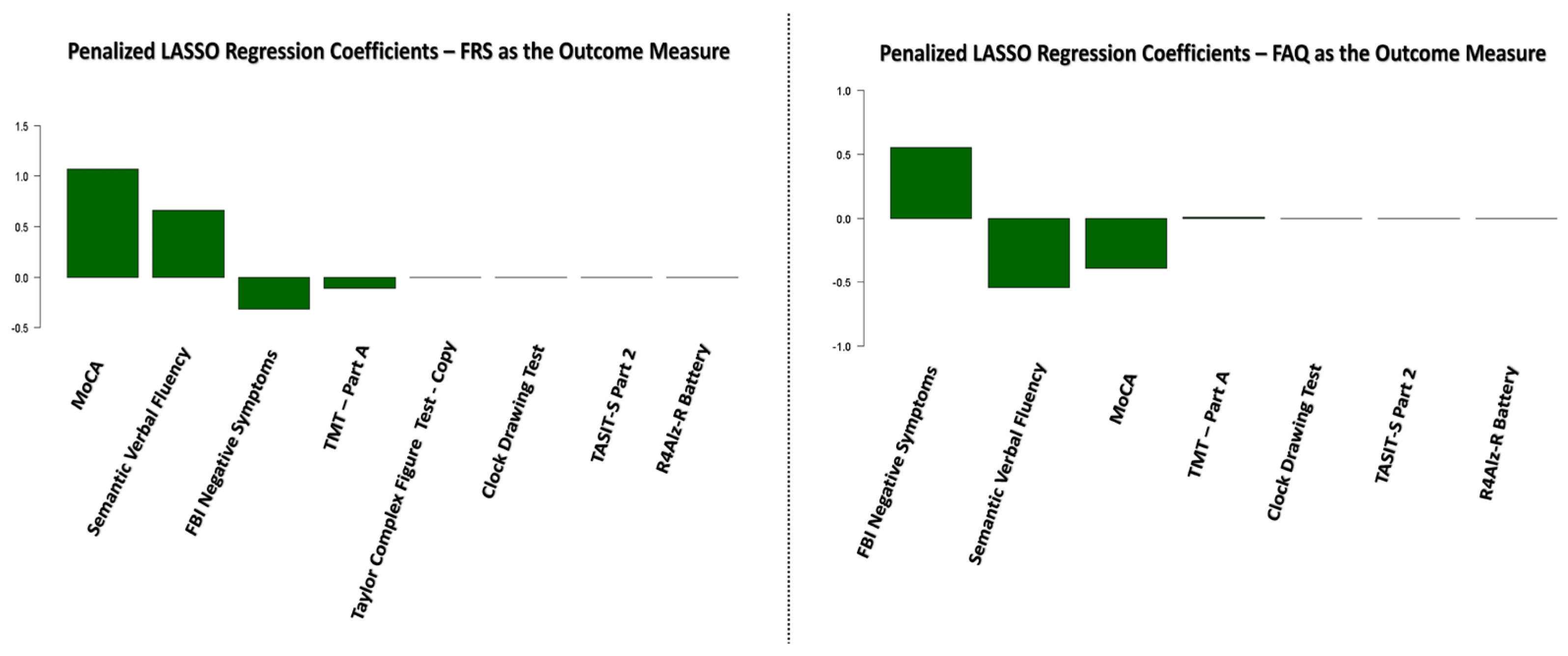

Results of the Penalized LASSO Regression Analysis

Brain Perfusion Contributions to Functional Status in bvFTD

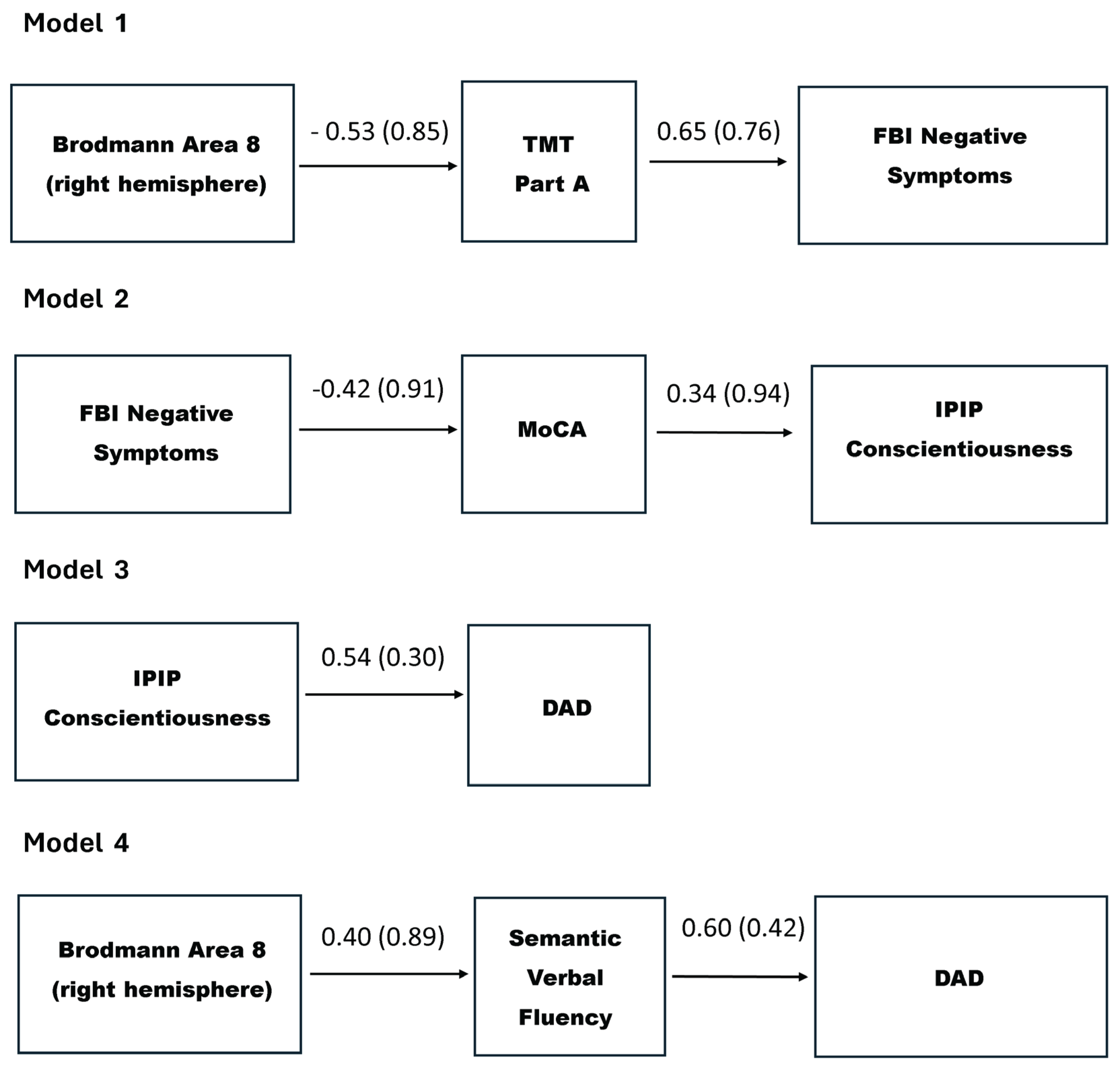

Path Analysis Results

4. Discussion

- Clinical Implications

Limitations

Strengths and Unique Contribution

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| bvFTD | Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia |

| FTLD LASSO |

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration Penalized Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator regression analysis |

| ADLs | Activities of daily living |

| BADLs | Basic activities of daily living |

| IADLs | Instrumental activities of daily living |

| SPECT | Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| rCBF | Regional Cerebral Blood Flow |

| BA | Brodmann area |

| AUTh | Aristotle University of Thessaloniki |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| CDT | Clock Drawing Test |

| TMT | Trail Making Test |

| FES | Frontier Executive Screen |

| R4Alz-R | REMEDES for Alzheimer-Revised battery |

| TASIT-S | The Awareness of Social Inference Test - Short |

| EET | Emotion Evaluation Test |

| SI-M | Test of Social Inference – Minimal |

| IPIP | Goldberg’s International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) Big-Five Questionnaire |

| FBI | Frontal Behavioral Inventory |

| CDR | Clinical Dementia Rating Scale |

| FTLD-CDR | Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration-Modified Clinical Dementia Rating Scale |

| FRS | Frontal Rating Scale |

| DAD | Disability Assessment for Dementia |

| FAQ | Functional Activities Questionnaire |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| Χ2 | Chi-square test |

References

- Hogan, D.B.; Jetté, N.; Fiest, K.M.; Roberts, J.I.; Pearson, D.; Smith, E.E.; Roach, P.; Kirk, A.; Pringsheim, T.; Maxwell, C.J. The Prevalence and Incidence of Frontotemporal Dementia: a Systematic Review. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 2016, 43, S96–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnavalli, E.; Brayne, C.; Dawson, K.; Hodges, J.R. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2002, 58, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rascovsky, K.; Hodges, J.R.; Knopman, D.; Mendez, M.F.; Kramer, J.H.; Neuhaus, J.; Van Swieten, J.C.; Seelaar, H.; Dopper, E.G.P.; Onyike, C.U.; Hillis, A.E.; Josephs, K.A.; Boeve, B.F.; Kertesz, A.; Seeley, W.W.; Rankin, K.P.; Johnson, J.K.; Gorno-Tempini, M.-L.; Rosen, H.; Prioleau-Latham, C.E.; Lee, A.; Kipps, C.M.; Lillo, P.; Piguet, O.; Rohrer, J.D.; Rossor, M.N.; Warren, J.D.; Fox, N.C.; Galasko, D.; Salmon, D.P.; Black, S.E.; Mesulam, M.; Weintraub, S.; Dickerson, B.C.; Diehl-Schmid, J.; Pasquier, F.; Deramecourt, V.; Lebert, F.; Pijnenburg, Y.; Chow, T.W.; Manes, F.; Grafman, J.; Cappa, S.F.; Freedman, M.; Grossman, M.; Miller, B.L. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011, 134, 2456–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima-Silva, T.B.; Bahia, V.S.; Nitrini, R.; Yassuda, M.S. Functional status in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, E.; Ioannidis, P.; Aretouli, E.; Papaliagkas, V.; Moraitou, D. Correlates of Functional Impairment in Patients with the Behavioral Variant of Frontotemporal Dementia: A PRISMA-Compliant Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, E.; Ioannidis, P.; Moraitou, D.; Konstantinopoulou, E.; Aretouli, E. The cognitive and behavioral correlates of functional status in patients with frontotemporal dementia: A pilot study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Bristow, M.; Cook, R.; Hodges, J.R. Factors underlying caregiver stress in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 2009, 27, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Kipps, C.M.; Dawson, K.; Mitchell, J.; Graham, A.; Hodges, J.R. Activities of daily living in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2007, 68, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Silva, T.B.; Bahia, V.S.; Carvalho, V.A.; Guimarães, H.C.; Caramelli, P.; Balthazar, M.; Damasceno, B.; De Campos Bottino, C.M.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Nitrini, R.; Yassuda, M.S. Functional profile of patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) compared to patients with Alzheimer’s disease and normal controls. Dementia & Neuropsychologia 2013, 7, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Hodges, J.R. Rate of change of functional abilities in frontotemporal dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 2009, 28, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devenney, E.; Bartley, L.; Hoon, C.; O’Callaghan, C.; Kumfor, F.; Hornberger, M.; Kwok, J.B.; Halliday, G.M.; Kiernan, M.C.; Piguet, O.; Hodges, J.R. Progression in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia. JAMA Neurology 2015, 72, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephs, K.A.; Whitwell, J.L.; Weigand, S.D.; Senjem, M.L.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Smith, G.E.; Ivnik, R.J.; Jack, C.R.; Petersen, R.C. Predicting functional decline in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011, 134, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Premi, E.; Gualeni, V.; Costa, P.; Cosseddu, M.; Gasparotti, R.; Padovani, A.; Borroni, B. Looking for measures of disease severity in the frontotemporal dementia continuum. Journal of Alzheimer S Disease 2016, 52, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanzio, M.; D’Agata, F.; Palermo, S.; Rubino, E.; Zucca, M.; Galati, A.; Pinessi, L.; Castellano, G.; Rainero, I. Neural correlates of reduced awareness in instrumental activities of daily living in frontotemporal dementia. Experimental Gerontology 2016, 83, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinacker, P.; Anderl-Straub, S.; Diehl-Schmid, J.; Semler, E.; Uttner, I.; Von Arnim, C.A.F.; Barthel, H.; Danek, A.; Fassbender, K.; Fliessbach, K.; Foerstl, H.; Grimmer, T.; Huppertz, H.-J.; Jahn, H.; Kassubek, J.; Kornhuber, J.; Landwehrmeyer, B.; Lauer, M.; Maler, J.M.; Mayer, B.; Oeckl, P.; Prudlo, J.; Schneider, A.; Volk, A.E.; Wiltfang, J.; Schroeter, M.L.; Ludolph, A.C.; Otto, M.; Albrecht, F.; Bisenius, S.; Feneberg, E.; Haefner, S.; Kasper, E.; Kurzwelly, D.; Lampe, L.; Levin, J.; Lornsen, F.; Luley, M.; Oberstein, T.; Pellkofer, H.; Prix, C.; Richter-Schmidinger, T.; Roth, N.; Sabri, O.; Schachner, L.; Schomburg, R.; Schönecker, S.; Schuemberg, K.; Spottke, A.; Teipel, S.; Wilken, P.; Zech, H. Serum neurofilament light chain in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2018, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benussi, A.; Dell’Era, V.; Cantoni, V.; Cotelli, M.S.; Cosseddu, M.; Spallazzi, M.; Micheli, A.; Turrone, R.; Alberici, A.; Borroni, B. TMS for staging and predicting functional decline in frontotemporal dementia. Brain Stimulation 2019, 13, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassuda, M.S.; Da Silva, T.B.L.; O’Connor, C.M.; Mekala, S.; Alladi, S.; Bahia, V.S.; Almaral-Carvalho, V.; Guimaraes, H.C.; Caramelli, P.; Balthazar, M.L.F.; Damasceno, B.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Nitrini, R.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O.; Mioshi, E. Apathy and functional disability in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology Clinical Practice 2018, 8, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Silva, T.B.; Bahia, V.S.; Carvalho, V.A.; Guimarães, H.C.; Caramelli, P.; Balthazar, M.L.F.; Damasceno, B.; De Campos Bottino, C.M.; Brucki, S.M.D.; Nitrini, R.; Yassuda, M.S. Direct and indirect assessments of activities of daily living in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2014, 28, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moheb, N.; Mendez, M.F.; Kremen, S.A.; Teng, E. Executive Dysfunction and Behavioral Symptoms Are Associated with Deficits in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Frontotemporal Dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 2017, 43, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salech, G.M.; Lillo, P.; Van Der Hiele, K.; Méndez-Orellana, C.; Ibáñez, A.; Slachevsky, A. Apathy, executive function, and emotion recognition are the main drivers of functional impairment in behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, E.; . Chen, Y.; Moraitou, D.; Ioannidis, P.; Aretouli, E.; Kramer, J.H.; Miller, B.L.; Gorno-Tempini, M.; Seeley, W.W.; Rosen, H.R.; Rankin, K.P. The Predictive Value of Social Cognition Assessment for 1-year Follow-Up Functional Outcomes in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia. Journal of Neurology.

- O’Connor, C.M.; Landin-Romero, R.; Clemson, L.; Kaizik, C.; Daveson, N.; Hodges, J.R.; Hsieh, S.; Piguet, O.; Mioshi, E. Behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2017, 89, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, C.M.; Clemson, L.; Hornberger, M.; Leyton, C.E.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O.; Mioshi, E. Longitudinal change in everyday function and behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology Clinical Practice 2016, 6, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipps, C.M.; Mioshi, E.; Hodges, J.R. Emotion, social functioning and activities of daily living in frontotemporal dementia. In Psychology Press eBooks; 2020; pp 182–189. [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros Correia Marin, S.; Mansur, L.L.; De Oliveira, F.F.; Marin, L.F.; Wajman, J.R.; Bahia, V.S.; Bertolucci, P.H.F. Swallowing in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Arquivos De Neuro-Psiquiatria 2021, 79, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverberi, C.; Cherubini, P.; Baldinelli, S.; Luzzi, S. Semantic fluency: Cognitive basis and diagnostic performance in focal dementias and Alzheimer’s disease. Cortex 2014, 54, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laisney, M.; Matuszewski, V.; Mézenge, F.; Belliard, S.; Sayette, V.; Eustache, F.; Desgranges, B. The underlying mechanisms of verbal fluency deficit in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. Journal of Neurology 2009, 256, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Segawa, E.; Sytsma, J.; Bennett, D.A. Conscientiousness, dementia related pathology, and trajectories of cognitive aging. Psychology and Aging 2015, 30, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Amin, N.; Van Duijn, C.; Littlejohns, T.J. Association of neuroticism with incident dementia, neuroimaging outcomes, and cognitive function. Alzheimer S & Dementia 2024, 20, 5578–5589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, L.-F.; Harrison, F.; Lackersteen, S.M. Does Personality affect Risk for dementia? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2013, 21, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaup, A.R.; Harmell, A.L.; Yaffe, K. Conscientiousness Is Associated with Lower Risk of Dementia among Black and White Older Adults. Neuroepidemiology 2019, 52, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Stephan, Y.; Terracciano, A. Facets of Conscientiousness and risk of dementia. Psychological Medicine 2017, 48, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, J.; Spina, S.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal dementia. The Lancet 2015, 386, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekiz, E.; Videler, A.C.; Van Alphen, S.P.J. Feasibility of the Cognitive Model for Behavioral Interventions in Older Adults with Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Clinical Gerontologist 2020, 45, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union 2016, 119, http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05–04. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MOCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounti, F.; Tsolaki, M.; Eleftheriou, M.; Agogiatou, C.; Karagiozi, K.; Bakoglidou, E.; Nikolaides, E.; Nakou, S.; Poptsi, E.; Zafiropoulou, M.; et al. Administration of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test in Greek healthy elderly, patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and patients with Dementia. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Psychological Assessment and 2th International Conference of the Psychological Society of Northern Greece, Thessaloniki, Greece, 5–7 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulos, K.; Vogazianos, P.; Doskas, T. Normative data of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in the Greek population and Parkinsonian dementia. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2016, 31, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poptsi, E.; Moraitou, D.; Eleftheriou, M.; Kounti-Zafeiropoulou, F.; Papasozomenou, C.; Agogiatou, C.; Bakoglidou, E.; Batsila, G.; Liapi, D.; Markou, N.; Nikolaidou, E.; Ouzouni, F.; Soumpourou, A.; Vasiloglou, M.; Tsolaki, M. Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in Greek older adults with subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2019, 32, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, M; Clock drawing: A neuropsychological analysis. Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Shulman, K.I. Clock-drawing: is it the ideal cognitive screening test? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2000, 15, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozikas, V.P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Hatzigeorgiadou, M.; Karavatos, A.; Kosmidis, M.H. Do age and education contribute to performance on the clock drawing test? Normative data for the Greek population. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 2008, 30, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, M.H.; Bozikas, V.; Vlahou, C.H.; Giaglis, G. Neuropsychological Battery. Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTh): Thessaloniki, Greece, 2011; Unpublished work.

- Taylor, E.M. Psychological Appraisal of Children with Cerebral Deficits; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Borod, J.C.; Goodglass, H.; Kaplan, E. Normative data on the boston diagnostic aphasia examination, parietal lobe battery, and the boston naming Test. Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology 1980, 2, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, R.M. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills 1958, 8, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsatali, M.; Surdu, F.; Konstantinou, A.; Moraitou, D. Normative data for the D-KEFS Color-Word interference and trail making tests adapted in Greek adult population 20–49 years old. NeuroSci 2024, 5, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalonis, I.; Kararizou, E.; Triantafyllou, N.I.; Kapaki, E.; Papageorgiou, S.; Sgouropoulos, P.; Vassilopoulos, D. A normative study of the trail making test A and B in Greek adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist 2008, 22, 842–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lezak, M.; Howieson, M.; Loring, D. Neuropsychological Assessment, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroop, J.R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology 1935, 18, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalonis, I.; Christidi, F.; Bonakis, A.; Kararizou, E.; Triantafyllou, N.I.; Paraskevas, G.; Kapaki, E.; Vasilopoulos, D. The Stroop effect in Greek healthy population: Normative data for the Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2009, 24, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmidis, M.H.; Vlahou, C.H.; Panagiotaki, P.; Kiosseoglou, G. The verbal fluency task in the Greek population: Normative data, and clustering and switching strategies. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2004, 10, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, F.V.C.; Foxe, D.; Daveson, N.; Flannagan, E.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O. FRONTIER Executive Screen: a brief executive battery to differentiate frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2015, 87, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinopoulou, E.; Vilou, I.; Falega, I.; Papadopoulou, V.; Chatzidimitriou, E.; Grigoriadis, N.; Aretouli, E.; Panagiotis, I. Screening for Executive Impairment in Patients with Frontotemporal Dementia: Evidence from the Greek Version of the Frontier Executive Screen. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poptsi, E.; Tsardoulias, E.; Moraitou, D.; Symeonidis, A.L.; Tsolaki, M. REMEDES for Alzheimer-R4ALZ Battery: Design and development of a new tool of Cognitive Control assessment for the diagnosis of minor and major neurocognitive disorders. Journal of Alzheimer S Disease 2019, 72, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poptsi, E.; Moraitou, D.; Tsardoulias, E.; Symeonidis, A.L.; Tsolaki, M. Subjective Cognitive Impairment Can Be Detected from the Decline of Complex Cognition: Findings from the Examination of Remedes 4 Alzheimer’s (R4Alz) Structural Validity. Brain Sciences 2024, 14, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poptsi, E.; Moraitou, D.; Tsardoulias, E.; Symeonidis, A.L.; Tsolaki, M. R4Alz-R: a cutting-edge tool for spotting the very first and subtle signs of aging-related cognitive impairment with high accuracy. GeroScience 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraitou, D.; Papantoniou, G.; Gkinopoulos, T.; Nigritinou, M. Older adults’ decoding of emotions: age-related differences in interpreting dynamic emotional displays and the well-preserved ability to recognize happiness. Psychogeriatrics 2013, 13, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.; Flanagan, S.; Honan, C. ; The Awareness of Social Inference Test – Short (TASIT-S). ASSBI Resources: Sydney, Australia, 2017.

- Tsentidou, G.; Moraitou, D.; Tsolaki, M. Similar Theory of Mind Deficits in Community Dwelling Older Adults with Vascular Risk Profile and Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: The Case of Paradoxical Sarcasm Comprehension. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, L.R.; Johnson, J.A.; Eber, H.W.; Hogan, R.; Ashton, M.C.; Cloninger, C.R.; Gough, H.G. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality 2005, 40, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment 1992, 4, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. The Five-Factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders 1992, 6, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ypofanti, M.; Zisi, V.; Zourbanos, N.; Mouchtouri, B.; Tzanne, P.; Theodorakis, Y.; Lyrakos, G. Psychometric properties of the International Personality Item Pool Big-Five personality questionnaire for the Greek population. Health Psychology Research 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertesz, A.; Davidson, W.; Fox, H. Frontal Behavioral Inventory: diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1997, 24, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertesz, A.; Nadkarni, N.; Davidson, W.; Thomas, A.W. The Frontal Behavioral Inventory in the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2000, 6, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, D.; Snowden, J.S.; Gustafson, L.; Passant, U.; Stuss, D.; Black, S.; Freedman, M.; Kertesz, A.; Robert, P.H.; Albert, M.; Boone, K.; Miller, B.L.; Cummings, J.; Benson, D.F. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 1998, 51, 1546–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinopoulou, E.; Aretouli, E.; Ioannidis, P.; Karacostas, D.; Kosmidis, M.H. Behavioral disturbances differentiate frontotemporal lobar degeneration subtypes and Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the Frontal Behavioral Inventory. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2012, 28, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, J.C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Neurology 1993, 43, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopman, D.S.; Kramer, J.H.; Boeve, B.F.; Caselli, R.J.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Mendez, M.F.; Miller, B.L.; Mercaldo, N. Development of methodology for conducting clinical trials in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain 2008, 131, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiovis, P.; Ioannidis, P.; Gerasimou, G.; Gotzamani-Psarrakou, A.; Karacostas, D. Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration-Modified Clinical Dementia Rating (FTLD-CDR) scale and Frontotemporal Dementia Rating Scale (FRS) correlation with regional brain perfusion in a series of FTLD patients. Journal of Neuropsychiatry 2016, 29, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopman, D.S.; Weintraub, S.; Pankratz, V.S. Language and behavior domains enhance the value of the clinical dementia rating scale. Alzheimer S & Dementia 2011, 7, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Hsieh, S.; Savage, S.; Hornberger, M.; Hodges, J.R. Clinical staging and disease progression in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2010, 74, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornari, X.; Tsantali, E.; Tsolaki, M.; Kigiaki, E. Do Functional Disability Is a Good Predictor Index for Alzheimer’s Disease? Annals of General Psychiatry 2006, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gélinas, I.; Gauthier, L.; McIntyre, M.; Gauthier, S. Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer’s disease: the Disability Assessment for Dementia. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 1999, 53, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, R.I.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Harrah, C.H.; Chance, J.M.; Filos, S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. Journal of Gerontology 1982, 37, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, Ö.L.; Nobili, F.; Varrone, A.; Booij, J.; Borght, T.V.; Någren, K.; Darcourt, J.; Tatsch, K.; Van Laere, K.J. EANM procedure guideline for brain perfusion SPECT using 99mTc-labelled radiopharmaceuticals, version 2. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2009, 36, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2025, Vienna, Austria.

- Zhou, D.J.; Chahal, R.; Gotlib, I.H.; Liu, S. Comparison of lasso and stepwise regression in psychological data. Methodology 2024, 20, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; An, S.; Hong, S. Exploring the factors that influence academic stress among elementary school students using a LASSO penalty regression model. Asia Pacific Education Review 2023, 25, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovens, I.B.; Dalenberg, J.R.; Small, D.M. A Brief Neuropsychological Battery for Measuring Cognitive Functions Associated with Obesity. Obesity 2019, 27, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, D.; Hsieh, S.; Caga, J.; Leslie, F.V.C.; Kiernan, M.C.; Hodges, J.R.; Mioshi, E.; Burrell, J.R. Motor function and behaviour across the ALS-FTD spectrum. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2015, 133, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P. M; EQS 6.4 for Windows [Computer Software]; Encino, CA: Multivariate Software Inc. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: AMOS, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bryant, S.E.; Waring, S.C.; Cullum, C.M.; Hall, J.; Lacritz, L.; Massman, P.J.; Lupo, P.J.; Reisch, J.S.; Doody, R. Staging dementia using Clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes scores. Archives of Neurology 2008, 65, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, M.A.L.; Jefferies, E.; Patterson, K.; Rogers, T.T. The neural and computational bases of semantic cognition. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 2016, 18, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhla, M.Z.; Banuelos, D.; Pagán, C.; Olvera, A.G.; Razani, J. Differences between episodic and semantic memory in predicting observation-based activities of daily living in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Applied Neuropsychology Adult 2021, 29, 1499–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, E.E.; Giovannetti, T.; Libon, D.J.; Eppig, J. Everyday task knowledge and everyday function in dementia. Journal of Neuropsychology 2017, 13, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, R.; Humphreys, G.F.; Jung, J.; Ralph, M. a. L. Controlled semantic cognition relies upon dynamic and flexible interactions between the executive ‘semantic control’ and hub-and-spoke ‘semantic representation’ systems. Cortex 2018, 103, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, L.; Poos, J.M.; Van Den Berg, E.; De Houwer, J.F.H.; Swartenbroekx, T.; Dopper, E.G.P.; Boesjes, P.; Tahboun, N.; Bouzigues, A.; Foster, P.H.; Ferry-Bolder, E.; Adams-Carr, K.; Russell, L.L.; Convery, R.S.; Rohrer, J.D.; Seelaar, H.; Jiskoot, L.C. Montreal Cognitive Assessment vs the Mini-Mental State Examination as a Screening Tool for Patients With Genetic Frontotemporal Dementia. Neurology 2025, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrides, M. Lateral prefrontal cortex: architectonic and functional organization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences 2005, 360, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadario, N.B.; Tanglay, O.; Sughrue, M.E. Deconvoluting human Brodmann area 8 based on its unique structural and functional connectivity. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, M.; Sadato, N.; Kochiyama, T.; Nakamura, S.; Naito, E.; Matsunami, K.-I.; Kawashima, R.; Fukuda, H.; Yonekura, Y. Role of the cerebellum in implicit motor skill learning: a PET study. Brain Research Bulletin 2004, 63, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouin, F.; Richards, C.L.; Jackson, P.L.; Dumas, F.; Doyon, J. Brain activations during motor imagery of locomotor-related tasks: A PET study. Human Brain Mapping 2003, 19, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler, A.; Dixon, V.; Garavan, H. Automaticity and Reestablishment of Executive Control—An FMRI study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2006, 18, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rämä, P.; Martinkauppi, S.; Linnankoski, I.; Koivisto, J.; Aronen, H.J.; Carlson, S. Working Memory of identification of Emotional Vocal Expressions: an FMRI study. NeuroImage 2001, 13, 1090–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Fujita, H.; Kanno, I.; Miura, S.; Tanaka, K. Human cortical regions activated by wide-field visual motion: an H2(15)O PET study. Journal of Neurophysiology 1995, 74, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.T. Brain correlates of stuttering and syllable production: A PET performance-correlation analysis. Brain 2000, 123, 1985–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carli, D.; Garreffa, G.; Colonnese, C.; Giulietti, G.; Labruna, L.; Briselli, E.; Ken, S.; Macrì, M.A.; Maraviglia, B. Identification of activated regions during a language task. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2007, 25, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godefroy, V.; Batrancourt, B.; Charron, S.; Bouzigues, A.; Bendetowicz, D.; Carle, G.; Rametti-Lacroux, A.; Bombois, S.; Cognat, E.; Migliaccio, R.; Levy, R. Functional connectivity correlates of reduced goal-directed behaviors in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain Structure and Function 2022, 227, 2971–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, Y. Brodmann Areas 39 and 40: human parietal association area and higher cortical function. PubMed 2017, 69, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silani, G.; Lamm, C.; Ruff, C.C.; Singer, T. Right supramarginal gyrus is crucial to overcome emotional egocentricity bias in social judgments. Journal of Neuroscience 2013, 33, 15466–15476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Trujillo, J. Visual attention in the prefrontal cortex. Annual Review of Vision Science 2022, 8, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesulam, M. Large-scale neurocognitive networks and distributed processing for attention, language, and memory. Annals of Neurology 1990, 28, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.; Kumfor, F. Overcoming apathy in frontotemporal dementia: challenges and future directions. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2018, 22, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).