1. Introduction

Dementia represents one of the most pressing global health challenges of the 21st century, affecting over 55 million people worldwide, with nearly 10 million new cases each year. As populations age, the prevalence of dementia is projected to triple by 2050, creating profound implications for healthcare systems, caregivers and society at large (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009; Livingston et al., 2024). Despite advances in understanding its pathophysiology, dementia remains a complex syndrome influenced by biological, psychological and social factors, necessitating multidimensional approaches to both research and care.

Traditional biomedical models have emphasized the role of neuropathology, particularly amyloid and tau accumulation, in the development of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. More recently, neuroimaging evidence has highlighted additional mechanisms such as demyelination, which appears to play a role in both mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia (Bouhrara et al., 2018). At the same time, protective factors across the life course, including education, occupation, lifestyle and social engagement, are recognized as contributors to the concept of cognitive reserve (Kim et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024; Roe et al., 2008). Individuals with higher education and richer cultural experiences tend to show delayed clinical manifestations of neuropathological burden, underscoring the relevance of sociodemographic context in dementia outcomes.

Multimorbidity and frailty are also highly prevalent in dementia populations, with cardiovascular, metabolic and nutritional issues frequently coexisting. Among them, appetite disturbances are particularly relevant, being linked to malnutrition, frailty and accelerated disease progression (Fostinelli et al., 2020; Scheufele et al., 2023; Yamamoto et al., 2020). Similarly, sleep disruptions are increasingly recognized not only as consequences of dementia but also as potential precursors of neurodegeneration, with recent evidence showing that sleep disturbances may precede diagnosis by more than a decade (Simmonds et al., 2025).

Beyond the biomedical framework, the social and cultural context profoundly shapes the dementia experience. Family networks often provide the primary source of support, especially in countries with limited formal services, but this reliance places a disproportionate burden on caregivers (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009). Spirituality, religious practices and alternative explanatory models may also influence coping strategies and health-seeking behavior. Recent studies indicate that higher levels of spirituality in persons with mild to moderate dementia are associated with slower cognitive decline and fewer neuropsychiatric symptoms (Britt et al., 2022), while qualitative evidence shows that caregivers often turn to prayer, faith and religious reading as mechanisms of resilience and meaning-making in the face of dementia (McGee et al., 2022). Such findings highlight the importance of perspectives that integrate cultural and anthropological insights into dementia research.

Taken together, these considerations underscore the importance of integrated, caregiver-informed research that accounts not only for biomedical and cognitive dimensions, but also for lifestyle, cultural and social determinants of health. This study seeks to contribute to this growing field by analyzing dementia through an anthropological perspective, focusing on caregiver-reported data on risk factors, behavioral manifestations, comorbidities and quality of life.

Despite the growing body of research on dementia, much of the existing literature remains dominated by biomedical models that focus primarily on neuropathology. While such approaches are fundamental to understanding disease mechanisms, they often overlook the lived experiences of patients and caregivers, as well as the broader sociocultural and lifestyle contexts in which dementia unfolds. Recent findings highlight the influence of multimorbidity, nutritional factors, sleep disturbances and social networks on the trajectory of dementia, yet these dimensions are still underrepresented in clinical and epidemiological research (Fostinelli et al., 2020; Simmonds et al., 2025; Scheufele et al., 2023).

In Romania and similar settings with limited formal dementia care infrastructure, caregiving is predominantly provided by family members. This reality not only places a considerable burden on caregivers but also makes their perceptions and reports a crucial source of knowledge regarding the manifestations and management of dementia. Caregivers are uniquely positioned to observe changes in appetite, sleep, activity, cognition and behavior over time, providing valuable insights that complement clinical assessments.

Furthermore, cultural and anthropological dimensions — including spirituality, religious practices and alternative explanatory models — shape coping strategies and health-seeking behaviors in ways that biomedical frameworks cannot fully capture (Britt et al., 2022; McGee et al., 2022). Integrating these perspectives allows for a more holistic understanding of dementia, particularly in contexts where formal healthcare services are fragmented and families rely on traditional, spiritual or community-based support systems.

In Romania and other Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, dementia and dementia care remain areas where formal support systems are underdeveloped, making family caregivers the primary providers of care. Recent initiatives, such as Strengthening Research Capacity and Policy Responses – Dementia Romania, have highlighted the urgent need for a coherent national dementia plan to ensure equitable access to diagnosis, outpatient services, long-term care, and psychosocial support for families. Studies show that Romanian general practitioners perceive their role in dementia detection and monitoring as limited due to insufficient training, scarce resources, and the lack of specialized services, particularly in rural communities (Sfetcu et al., 2021). Comparative European analyses further underline major regional disparities in dementia care provision: in Romania, services are fragmented and concentrated mainly in urban centers, with restricted access in rural areas (Schmachtenberg et al., 2022). Under these conditions, caregivers’ perceptions—regarding state support, stigma, cultural beliefs, or the role of religion—are not peripheral, but central to the way dementia is experienced, understood, and managed.

The present study addresses these gaps by adopting an anthropological perspective on dementia, using caregiver-reported data to explore risk factors, comorbidities, behavioral manifestations and quality of life. This approach not only enriches our understanding of dementia beyond neuropathology but also emphasizes the voices of caregivers as key informants in shaping both scientific inquiry and care practices. By situating biomedical, behavioral and cultural aspects within the same analytic framework, the study seeks to contribute evidence that is both contextually grounded and globally relevant.

2. Materials and Methods

This investigation was conceived as a single-center, observational, analytical cross-sectional study aimed at exploring the interplay between biomedical, behavioral and sociocultural dimensions of dementia, as perceived and reported by family caregivers. A total of 73 caregivers of patients with a clinical diagnosis of dementia were recruited between November 2023 and April 2024 from the Neurology–Psychiatry Department of the C.F.2 Clinical Hospital in Bucharest, Romania.

Eligibility criteria were designed to ensure that participants possessed both sustained caregiving experience and the ability to provide valid insights. Caregivers were included if they were aged 30 years or older, were a family member of the person with dementia, had been engaged in caregiving for at least six months and were actively involved in the care process at the time of recruitment. Exclusion criteria eliminated non-family caregivers and respondents with incomplete questionnaire data. Of 120 individuals seeking dementia-related services during the study period, 73 met these criteria and were enrolled.

Data collection combined standardized psychological instruments with context-specific measures to capture both clinical and anthropological dimensions of dementia. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores were extracted from medical records of the patients (at diagnosis). To address the cultural and social context of dementia, an Anthropological Questionnaire (AQ) was specifically developed for this study, gathering socio-demographic information, lifestyle habits, beliefs and perceptions regarding the illness and caregiving. A pilot test with 15 formal caregivers was conducted to refine the AQ in orfer to design its final version.

Written informed consent was obtained from all caregiver participants, with explicit clarification that data regarding patients’ cognitive status were retrieved exclusively from medical records in a de-identified form, thus ensuring confidentiality and obviating the need for separate patient consent. The protocol received full approval from the Ethics Committee of C.F.2 Clinical Hospital (Reference No. 1781/06.02.2023). Participants were fully informed about the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks and benefits and assured of their right to withdraw at any stage without repercussions for themselves or their relatives’ access to medical care. Data storage and analysis were performed in aggregate form, guaranteeing anonymity.

3. Results

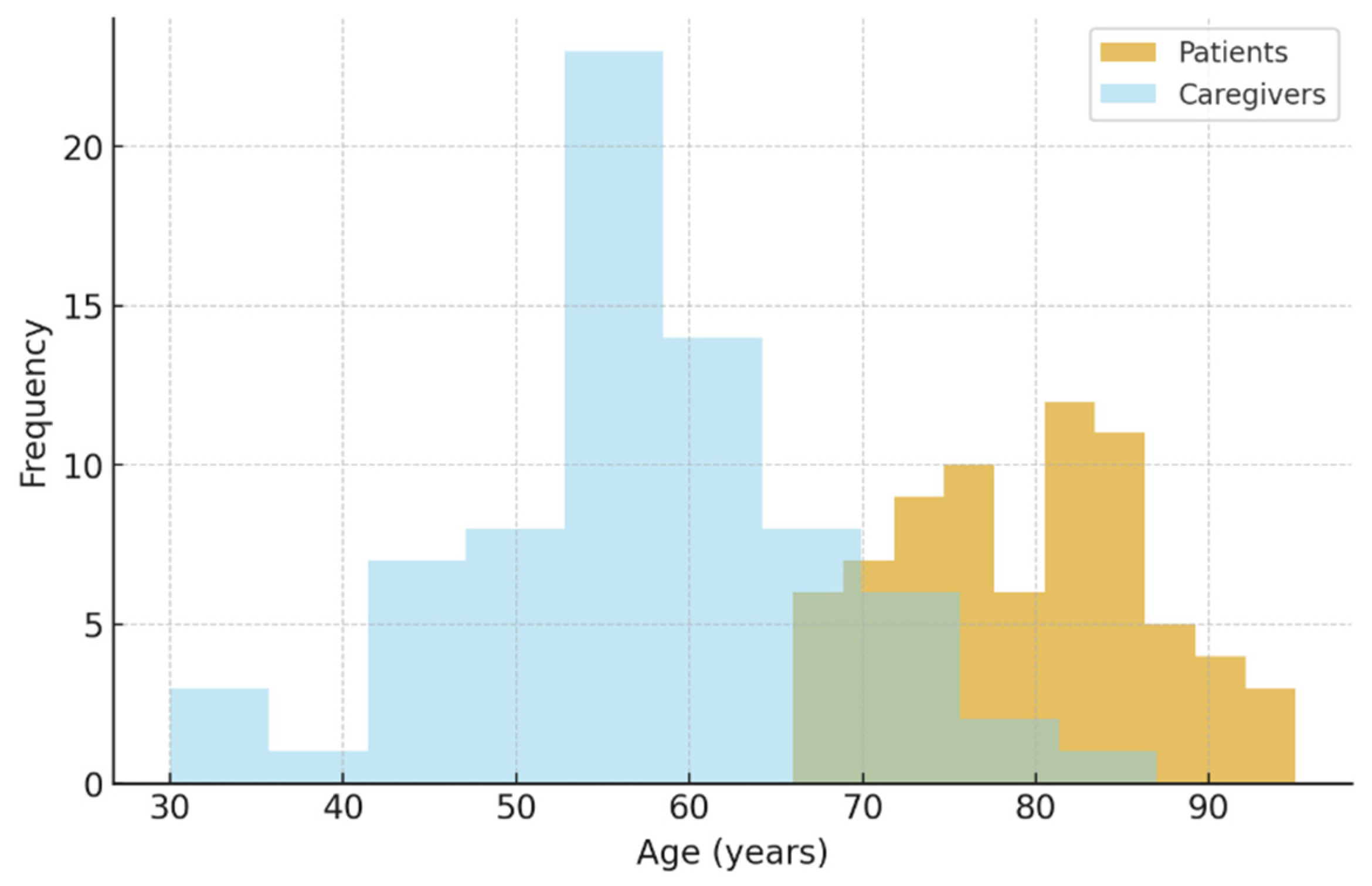

Seventy-three patients diagnosed with dementia were included in this study, based on caregiver reports. The mean age was 79 years (range 66–95) (

Table 1,

Figure 1). The mean body weight was 72.6 kg (SD = 15.3) and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.9 kg/m² (SD = 4.8), placing the average patient in the overweight category. Only 11 (15.1%) of the pacients were living alone, the others residing in households with a mean size of 3 members.

Educational level was generally modest, with only a few individuals having completed higher education. Cognitive impairment in care recipients was marked (MMSE M = 11.47, SD = 7). When cognitive performance was examined across educational strata, clear differences emerged. Patients with only secondary education had the lowest average MMSE scores (9.7 ± 5.8), pointing to a greater degree of impairment in this group. In contrast, those who had completed high school demonstrated higher cognitive scores on average (14.3 ± 7.9), while the small group with higher education (n = 3) also showed relatively preserved performance (13.0 ± 8.8). Although variability was considerable across all groups, the trend suggests that greater educational attainment was associated with better MMSE outcomes, in line with the cognitive reserve hypothesis. Household income clustered mainly below 1,000 EUR/month, with a substantial group (n=43, 58.9%) in the 400–1000 EUR bracket and a smaller fraction above 1,000 EUR (12.3%).

Chronic conditions were highly prevalent among the participants, reflecting the complex health profiles that often accompany dementia. Neurological disorders affected 84.9% of the sample, while cardiovascular diseases were also very frequent (68.5%). In contrast, pulmonary and digestive conditions were reported appeared only in a minority of cases, suggesting a less central role in this cohort. Metabolic (27.4%) and endocrine disorders (15.1%), although less widespread than neurological and cardiovascular diseases, contributed significantly to the overall burden. On average, individuals presented with 2.22 ± 1.03 comorbidities (median 2, IQR 2–3, range 0–6), a burden that is consistent with the advanced age of the sample and reflects the cumulative health challenges typically observed in older adults living with dementia (

Table 2). In subsequent analyses, comorbidity count showed no association with age (Spearman ρ = –0.026; p = 0.824) or age strata (65–74, 75–84, ≥85 years: 2.18 ± 0.85 vs 2.27 ± 0.98 vs 2.17 ± 1.34; χ² = 0.48; p = 0.788) and did not differ by appetite or sleep (p>0.99 and p = 0.167, respectively) (

Table 2).

In subsequent analyses, comorbidity count showed no association with age (Spearman ρ = –0.026; p = 0.824) or age strata (65–74, 75–84, ≥85 years: 2.18 ± 0.85 vs 2.27 ± 0.98 vs 2.17 ± 1.34; χ² = 0.48; p = 0.788) and did not differ by appetite or sleep (p>0.99 and p = 0.167, respectively).

Appetite changes were frequently reported (reduced/affected - 60.3%) (

Table 3). Despite this, BMI did not differ across appetite categories (Kruskal–Wallis χ² = 6.68; p = 0.352). By contrast, appetite was strongly linked to sleep (χ² = 159.44; df = 36; p < 0.0001), physical activity (χ² = 394.40; df = 282; p < 0.001), with reduced appetite clustering alongside sleep disturbance and low activity.

Smoking status alcohol consumption was also assessed. 18 participants (24.7%) were identified as smokers, while 55 (75.3%) were non-smokers. Alcohol consumption varied by beverage type , but was mostly reduced (

Table 4).

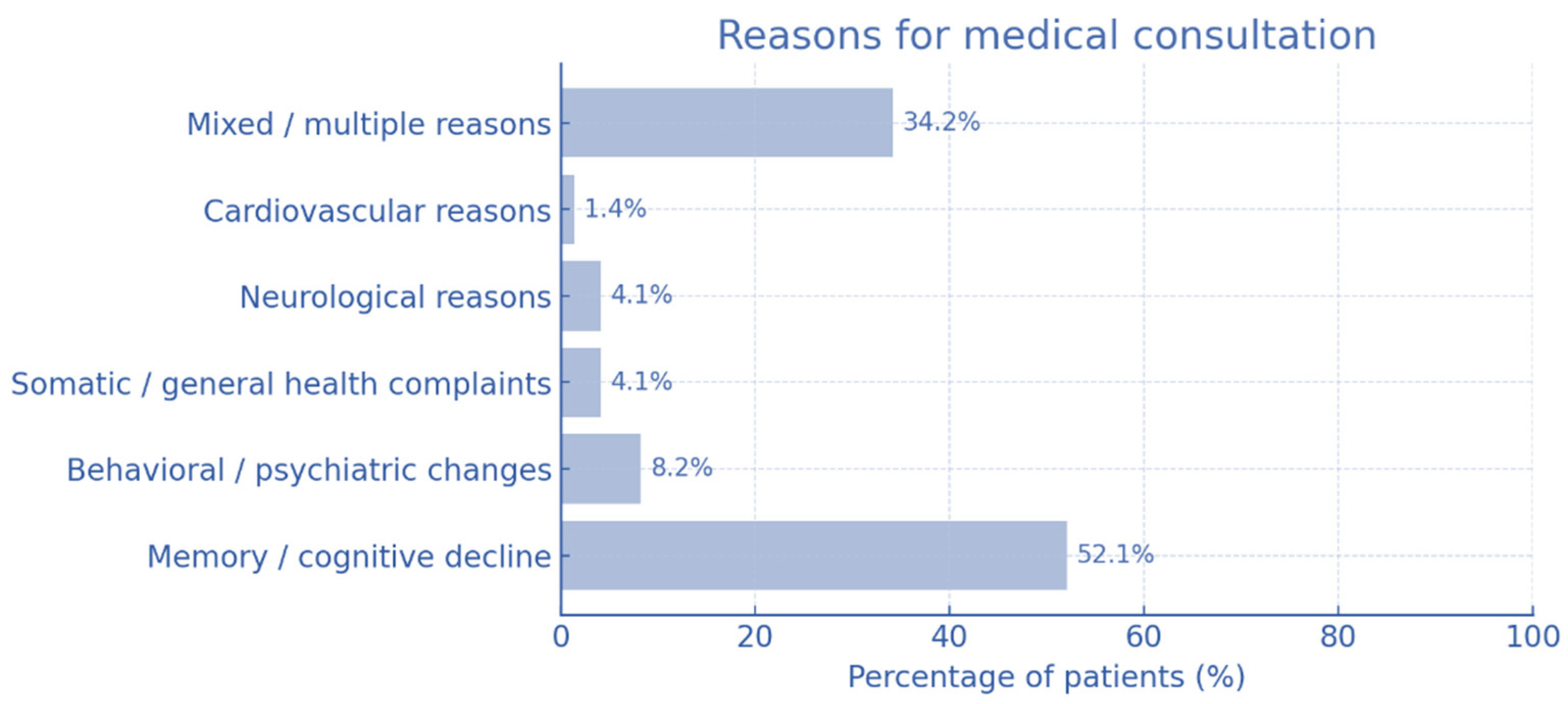

Caregivers most often reported memory impairment and cognitive decline as the presenting complaints, followed by confusion, disorientation and progressive deterioration (

Figure 2). In many cases, multiple symptoms coexisted, reflecting overlapping cognitive and behavioral issues that prompted medical consultation that lead to diagnosing dementia.

Disclosure of the dementia diagnosis to patients was reported by most caregivers, although not uniformly. In nearly three-quarters of cases (74%), the diagnosis was explicitly communicated, while about one-quarter (26%) of patients were not informed. Patients’ initial reactions to disclosure varied widely (Table 16). Some caregivers described emotional shock, sadness or crying (15.1%), while others reported denial or outright refusal of the diagnosis (16.4%). A substantial proportion reacted with confusion or lack of understanding (13.7%), consistent with cognitive decline at the time of disclosure. Acceptance—whether immediate or gradual—was described in 12.3% of cases, while smaller groups displayed indifference or minimization (6.8%) or marked anxiety and worry (8.2%). Almost one-third of accounts (27.4%) fell into mixed or less clearly defined categories, highlighting the heterogeneity of responses.

Family members also displayed a spectrum of reactions. The most frequent were worry and concern (27.4%) and anxiety, panic or sadness (20.5%). Some caregivers reported acceptance and a supportive stance (12.3%), while others described denial or refusal (5.5%) or indifference (2.7%). Notably, nearly one-third (31.5%) of family reactions were mixed, suggesting that adjustment to the diagnosis was often uneven across family members.

When describing patients’ current positioning toward their illness, caregivers reported a similarly diverse landscape. While confusion and lack of understanding were still frequent (19.2%), other patients exhibited persistent sadness and crying (12.3%), indifference (8.2%) or denial/refusal (9.6%). A minority demonstrated partial or gradual acceptance (11.0%) and some combined refusal with partial adherence to treatment (4.1%). A large proportion (35.6%) fell into heterogeneous or mixed categories, reflecting the dynamic and fluctuating process of adaptation as perceived by caregivers.

Taken together, these findings indicate that disclosure and adjustment to dementia diagnosis are not linear but rather oscillate between acceptance, confusion, denial and distress, influenced by both the patient’s cognitive state and the family’s interpretive frameworks.

According to caregiver reports, 12 patients (16.4%) had a positive family history of dementia, while 53 (72.6%) did not and in 8 (11.0%) cases the information was missing or unclear. In those with a positive history, the most frequently affected relatives were parents (7 patients, 58.3%), followed by siblings (4, 33.3%). In one case the affected relative was unspecified.

Mealtime behaviors (eating independently, meal regularity, meals/day, skipped meals and reasons) are ilustrated in

Table 5, outlining fragile routines with missed meals due to poor appetite, forgetfulness or distraction

Food-group consumption (fruits, vegetables, animal-source foods, cereals, milk/dairy) is summarized in

Table 6. Milk/dairy differed by appetite category (χ² = 14.71; p = 0.023), while the other food groups did not.

Supplement use and stimulants intake (coffee/tea/cola/energy drinks) were modest overall (

Table 7).

Some of the care recipients slept separately from spouse/family (61.6%), reflecting household adaptations to nocturnal symptoms.

Physical activity was generally low, ranging from minimal in-home movement to homebound/bedbound status; only 5% reported performing consistent chores or structured exercise (

Table 8). BMI did not differ by activity (χ² = 50.84; p = 0.401) or sleep (χ² = 5.74; p = 0.453).

Family relationships were mostly positive, though a non-negligible minority reported limited, strained or absent ties. Friendships were commonly reduced or absent, consistent with social network narrowing as disease advances (

Table 9).

Regarding sources of support, caregivers almost unanimously endorsed family and expressed high confidence in medical assistance; hope and lifestyle/diet were frequently mentioned. Religious resources (faith in God) were salient for many, while the priest’s role varied. Alternative practices (bioenergy, “breaking curses”) were rarely endorsed (

Table 10).

At the institutional level, state support was acknowledged by a majority of caregivers, although it primarily referred to the disability allowance received by patients, whereas NGO/association involvement was virtually absent (

Table 11).

Narrative items captured whether dementia diagnostic was disclosed to the patient and the following emotional reactions—for both patients and relatives—together with the current stance toward the diagnosis. In a considerable proportion of cases, caregivers reported that the patient had not been informed, either intentionally or because of perceived lack of benefit.

Patients’ immediate emotional responses upon learning of their diagnosis ranged widely, from acceptance or calm resignation reported in some cases, to shock, sadness or anxiety in many others. A smaller subset demonstrated denial or refusal to acknowledge the diagnosis, while others displayed indifference or had not been informed at all.

Family reactions mirrored this heterogeneity. While some relatives reported acceptance and readiness to adapt, many described distress, sadness or anxiety and a notable minority exhibited denial or avoidance behaviors.

The patients’ current stance toward their diagnosis changed over time, a portion of patients appeared more accepting and calm, whereas others continued to demonstrate anxiety, sadness or denial. Caregivers frequently highlighted emotional ambivalence, suggesting that adaptation to the diagnosis was not linear but rather an ongoing process shaped by disease progression, personality and family context.

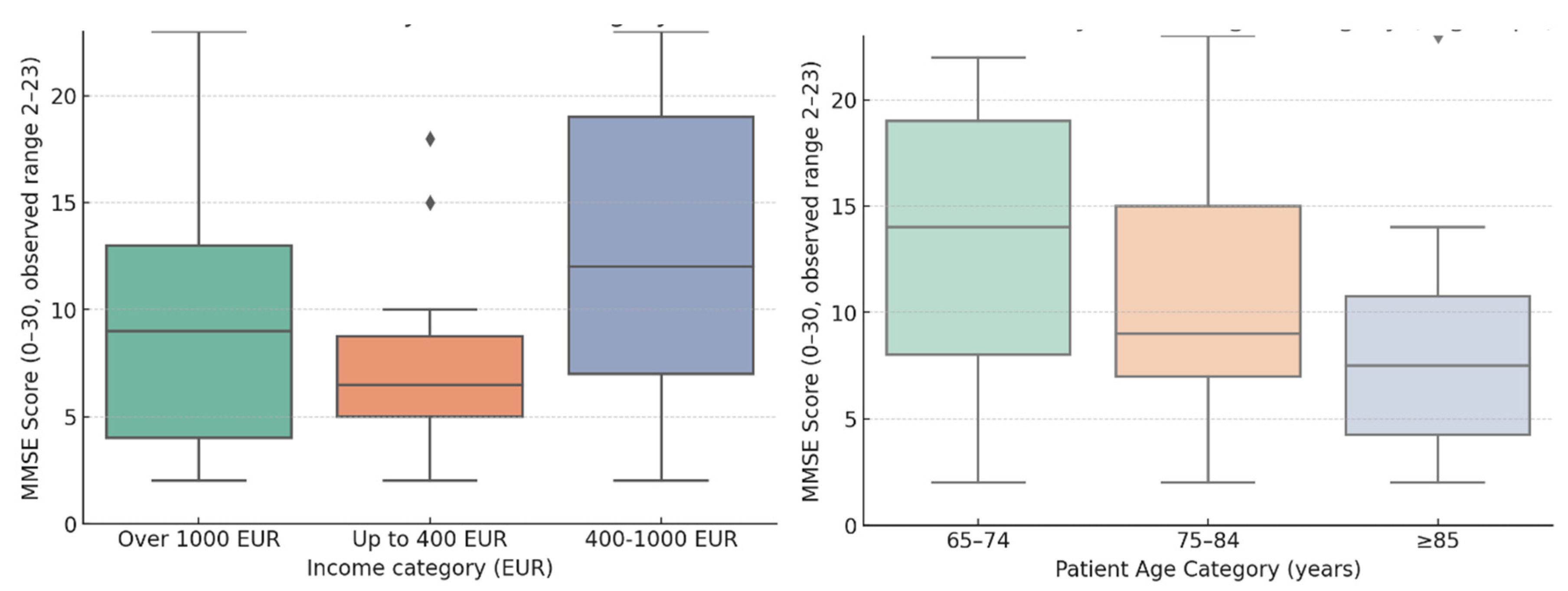

Most patients falling into severe impairment category and only a minority in mild impairment. We performed a bivariate analyses and found that age was significantly associated with MMSE category (Kruskal–Wallis χ² = 4.77; p = 0.029), delineating a gradient from mild impairment at younger ages to severe impairment in the oldest groups. Income showed a trend (χ² = 5.69; p = 0.058), whereas appetite, sleep, BMI, physical activity and comorbidity count were not related to MMSE status. MMSE scores were higher among those with greater education and varied across income categories (

Figure 3).

The association matrix and network highlighted age as the principal correlate of MMSE category, with income near significance. In a multivariable logistic model (mild vs severe impairment; factors: age, education, income, BMI, comorbidities, appetite, sleep, activity), no factor reached statistical significance; the largest, though nonsignificant, effects were education (OR = 2.56; 95% CI 0.70–9.32) and age (OR = 0.94; 95% CI 0.85–1.03). Beyond statistical thresholds, the overall pattern suggests that socio-educational resources and advancing age shape cognitive profiles, while somatic load (BMI, multimorbidity) likely exerts a less direct influence at this stage.

4. Discussion

This caregiver-based study provides an integrated perspective on the clinical, lifestyle and social dimensions of dementia in older adults. Several findings deserve emphasis.

The sample was characterized by advanced age, relatively low educational attainment and limited financial resources. These sociodemographic features are relevant because both education and income showed associations with MMSE score. This observation aligns with the concept of cognitive reserve, according to which higher education and better socioeconomic conditions may mitigate the clinical expression of neuropathology (Kim et al., 2024; Wilson et al., 2019; Roe et al., 2008).

The burden of multimorbidity was high, with an average of more than two chronic conditions per patient, dominated by neurologic and cardiovascular diseases. Yet, comorbidity count was not significantly related to cognitive status, suggesting that although prevalent, multimorbidity may exert indirect rather than direct effects on cognition, possibly through functional decline and reduced resilience. Similar findings have been reported in population-based cohorts, where somatic burden predicted frailty but not always cognitive performance (Liu et al., 2024).

Appetite and sleep disturbances were commonly reported and strongly interrelated. Reduced appetite co-occurred with poor sleep and low physical activity, pointing to a frailty-like syndrome that extends beyond cognition. Although not directly linked to MMSE categories in our data, these patterns resonate with previous work emphasizing the clustering of behavioral and nutritional symptoms in dementia (Fostinelli et al., 2020). Importantly, large-scale cohort studies demonstrate that sleep disturbances can precede dementia by many years and act as risk factors for neurodegeneration, even independent of genetic predisposition (Simmonds et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2018).

Lifestyle behaviors such as smoking and alcohol use were infrequent, reflecting either underreporting or genuine abstinence in a frail elderly sample. Nutritional patterns were dominated by staple foods, with only dairy intake differing significantly by appetite status. These results echo evidence linking dietary variety, appetite and sleep quality with cognitive decline risk in older adults (Shang et al., 2021; Yamamoto et al., 2023).

Social environment emerged as a crucial domain. Family relationships were described as supportive, whereas friendships and community ties were weak. Caregivers perceived only partial support from the state and almost no involvement of NGOs. These findings are consistent with other reports from Central and Eastern Europe that underline the fragility of community dementia services and the reliance on family-based care. Religious beliefs and, occasionally, alternative practices were integrated into coping narratives, reflecting the cultural context in which dementia care is embedded.

Finally, diagnostic disclosure generated heterogeneous reactions—ranging from acceptance to denial, sadness or indifference—highlighting the diversity of coping mechanisms among patients and families. These results underscore the importance of communication strategies that are sensitive to cultural and individual differences.

Overall, our study suggests that in this population, cognitive status is more closely linked to age and educational background than to somatic comorbidities or lifestyle habits. The picture that emerges is one of multidimensional vulnerability, in which biological, psychosocial and cultural determinants intersect.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study have several practical implications for dementia care. The strong influence of education and age on cognitive status suggests that strategies to promote cognitive reserve across the life course remain essential, even in late life. Interventions that stimulate cognitive activity, encourage engagement in meaningful tasks and adapt communication to educational background may help sustain residual function and quality of life.

Equally, the high prevalence of appetite and sleep disturbances points to the need for routine screening and integrated management of these symptoms in dementia care. Addressing sleep hygiene, tailoring dietary support and promoting small but regular physical activity could mitigate frailty-like features that often compound cognitive decline. These domains represent modifiable targets where caregiver guidance and clinical monitoring can have a direct impact.

The centrality of family support highlights both a strength and a vulnerability: while families remain the cornerstone of care, they also carry a disproportionate burden in the absence of robust formal services. Strengthening community-based support systems, expanding the role of NGOs and ensuring consistent state involvement are therefore critical. Importantly, the integration of caregiver perspectives into individualized care planning should become standard practice, as caregivers provide crucial insights into patient needs and daily realities.

The heterogeneity of reactions to diagnostic disclosure underscores the necessity of personalized communication strategies. Clinicians should adapt their approach to cultural values, family dynamics and individual coping styles, recognizing that acceptance, denial and ambivalence may coexist over time. Dementia care should evolve beyond a narrow biomedical framework to embrace multimodal, culturally sensitive approaches that address biological, behavioral and social dimensions. Such strategies hold the potential not only to improve patient well-being but also to alleviate the substantial burden borne by caregivers.

5. Conclusions

This caregiver-based study provides a multidimensional view of dementia in older adults, highlighting the intersection of sociodemographic, clinical, behavioral and cultural factors. Our findings suggest that cognitive outcomes are more strongly influenced by age and educational attainment than by comorbidities, nutritional status or lifestyle factors, supporting the concept of cognitive reserve (Kim et al., 2024; Wilson et al., 2019).

Disturbances of appetite and sleep emerged as frequent and interrelated, forming part of a broader syndrome of frailty that extends beyond cognition. These results are consistent with evidence that behavioral and nutritional symptoms play a critical role in dementia trajectories (Fostinelli et al., 2020; Yamamoto et al., 2023). Moreover, recent longitudinal data indicate that sleep disturbances may precede neurodegeneration by over a decade, even in individuals with low genetic risk (Simmonds et al., 2025).

Social and institutional dimensions also proved central. While family support was nearly universal, friendships were scarce and state or NGO involvement was limited, confirming the reliance on informal caregiving in Central and Eastern Europe (Oprea, 2024). Religious beliefs and alternative practices added further layers of cultural context to coping strategies.

Taken together, these findings emphasize the need for comprehensive, multimodal interventions that address not only the medical aspects of dementia but also nutrition, sleep, physical activity and social support. Strengthening formal care systems and integrating caregiver perspectives into personalized care plans represent urgent priorities for both practice and policy.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

The study offers a comprehensive caregiver-based dataset spanning clinical, lifestyle and social dimensions. Limitations include the small sample size, the underrepresentation of higher education and income groups, the reliance on caregiver reports (which may introduce subjectivity) and the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference.

Despite these limitations, the findings highlight the need for multimodal interventions that address medical, nutritional, sleep, activity and social needs. Policy should strengthen both state and NGO involvement, while clinical practice should integrate caregiver perspectives into individualized care plans.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; formal analysis, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; investigation, L.F.T.; methodology, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; software, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; supervision, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; validation C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; writing—original draft, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, C.S.G., L.F.T. and S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of C.F.2 Clinical Hospital (Ref. Number: 1781; and the approval date is 6 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouhrara, M.; Reiter, D.A.; Bergeron, C.M.; Zukley, L.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Resnick, S.M.; Spencer, R.G. Evidence of Demyelination in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Using a Direct and Specific Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measure of Myelin Content. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2018, 14, 998–1004. [CrossRef]

- Brodaty, H.; Donkin, M. Family Caregivers of People with Dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2009, 11, 217–228. [CrossRef]

- Fostinelli, S.; De Amicis, R.; Leone, A.; Giustizieri, V.; Binetti, G.; Bertoli, S.; Battezzati, A.; Cappa, S.F. Eating Behavior in Aging and Dementia: The Need for a Comprehensive Assessment. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 604488. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Stern, Y.; Seo, S.W.; Na, D.L.; Jang, J.; Jang, H.; Cognitive Reserve Research Group of Korea Dementia Association Factors Associated with Cognitive Reserve According to Education Level. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2024, 20, 7686–7697. [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.; Priest, A.; Delaney, T.; Hogan, J.; Herrawi, F. Toward Pre-Diagnostic Detection of Dementia in Primary Care. JAD 2022, 86, 479–490. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, G.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Gong, W. Cognitive Reserve over the Life Course and Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1358992. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care: 2024 Report of the Lancet Standing Commission. The Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.S.; Davie, M.; Meraz, R.; Myers, D.; Boddie, S.C. Does the Tough Stuff Make Us Stronger? Spiritual Coping in Family Caregivers of Persons with Early-Stage Dementia. Religions 2022, 13, 756. [CrossRef]

- Roe, C.M.; Mintun, M.A.; D’Angelo, G.; Xiong, C.; Grant, E.A.; Morris, J.C. Alzheimer Disease and Cognitive Reserve: Variation of Education Effect With Carbon 11–Labeled Pittsburgh Compound B Uptake. Arch Neurol 2008, 65, 1467. [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, P.; Rappl, A.; Visser, M.; Kiesswetter, E.; Volkert, D. Characterisation of Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Poor Appetite. Eur J Nutr 2023, 62, 1991–2000. [CrossRef]

- Schmachtenberg, T.; Monsees, J.; Thyrian, J.R. Structures for the Care of People with Dementia: A European Comparison. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 1372. [CrossRef]

- Sfetcu, R.; Toma, D.; Tudose, C.; Vladescu, C. Romanian GPs Involvement in Caring for the Mental Health Problems of the Elderly Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 641217. [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, E.; Levine, K.S.; Han, J.; Iwaki, H.; Koretsky, M.J.; Kuznetsov, N.; Faghri, F.; Solsberg, C.W.; Schuh, A.; Jones, L.; et al. Sleep Disturbances as Risk Factors for Neurodegeneration Later in Life. npj Dement. 2025, 1, 6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).