Introduction

Dementia is characterized by the progressive deterioration of multiple cognitive functions, leading to functional impairment. Alongside these cognitive deficits, neuropsychiatric (NP) symptoms are also commonly observed [

1]. While traditionally believed to manifest only in the advanced stages of the disease, recent studies have shown that NP symptoms can emerge as early as the prodromal stages. These symptoms significantly contribute to the burden experienced by caregivers [

2,

3].

Research on Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), in particular, has demonstrated that depression is more prominent in the early stages of the disease, whereas delusions and hallucinations tend to dominate in later stages. Apathy, however, is frequently observed throughout all stages of AD [

4]. Notably, apathy is not limited to AD but is also present across various types of dementia [

5].

Apathy is characterized by symptoms such as loss of motivation, reduced goal-directed behavior, diminished cognitive activity, and decreased emotional expression, persisting for at least four weeks [

6]. It is among the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia syndromes and has been suggested to play a prognostic role in the progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia [

4,

7,

8]. Consequently, some studies propose that apathy could serve as a predictor of dementia through non-invasive methods [

9]. However, if not specifically assessed, apathy can be difficult to recognize and challenging to manage.

In this study, we investigated the frequency of apathy in dementia patients across different types of dementia and examined its relationship with other neuropsychiatric symptoms, cognitive functions, and cranial imaging findings.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study included 200 patients followed at the Dementia Clinic of Sancaktepe Prof. Dr. İlhan Varank Training and Research Hospital, along with 100 healthy volunteers (HV). Diagnoses of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) were made based on the criteria of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) [

10]. For Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), the International Behavioural Variant FTD Criteria Consortium criteria were applied [

11]. The International Society of Vascular Behavioural and Cognitive Disorders criteria were used for Vascular Dementia (VD) [

12], while the revised criteria proposed by McKeith et al. in 2017 were employed for Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) [

13].

Patients were included in the study regardless of dementia stage. All participants were informed about the study, and consent was obtained either from the patients themselves or their legal guardians. Participants were matched for age, sex, and education level. Patients with any condition impairing physical functionality within the past six months were excluded.

Demographic data and disease onset durations were recorded. Apathy was evaluated in both the patient and HV groups using the Apathy Evaluation Scale. In the patient group, depression and anxiety levels were assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale and the Geriatric Anxiety Scale. Cognitive status was evaluated with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were analyzed using atrophy scales.

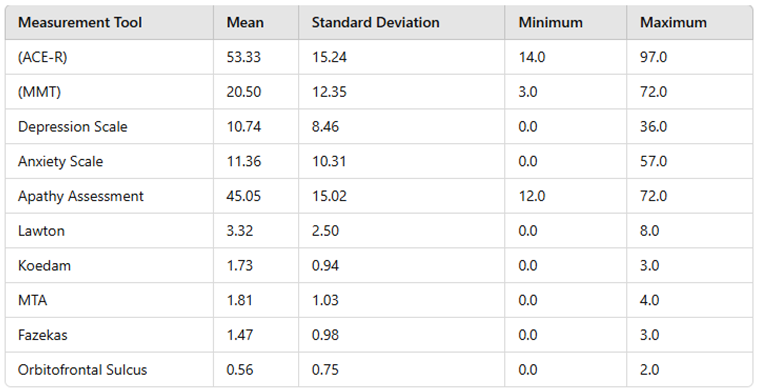

Table 1.

Mean, Minimum, Maximum, and Standard Deviation Values of Measurement Tools.

Table 1.

Mean, Minimum, Maximum, and Standard Deviation Values of Measurement Tools.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE):

The MMSE, developed by Folstein et al. in 1975, has undergone validation studies in Turkish [

14,

15]. It evaluates cognitive function across five sections: orientation, registration, attention/calculation, language, and recall. The maximum score is 30. Score ranges are categorized as follows: 0–9 indicates severe cognitive impairment, 10–19 indicates moderate cognitive impairment, 20–23 indicates mild cognitive impairment, and 24–30 is considered "normal cognitive functioning."

Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R):

The ACE-R is particularly sensitive in differentiating early-stage dementia. It assesses five subdomains: attention/orientation, memory, verbal fluency, language, and visuospatial abilities. The test has been adapted and validated for use in Turkish [

16,

17].

Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES):

The AES measures the prevalence and severity of apathy by evaluating behavioral, cognitive, and social/emotional domains of indifference and lack of motivation over the past four weeks [

18]. A Turkish validity and reliability study has been conducted (Gülseren et al., 2001, Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 38(3), 142–150). The scale comprises 18 items, with scores ranging from 18 to 72, where higher scores indicate greater levels of apathy. Both self-report and clinician-administered forms are available; in this study, the self-report form was used. Scores of 25 or above were considered indicative of apathy.

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS):

The GDS is a self-report scale consisting of 30 questions designed to detect depressive symptoms in the elderly population [

19]. The scale has been validated for reliability and validity in the Turkish population (Ertan, T., Eker, E., & Şar, V., 1997. Validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Scale in the Turkish elderly population.

Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 34(1), 62–71). Each question uses a binary response format ("yes" or "no"), with responses indicative of depression scored as 1 point, and others scored as 0. Higher scores indicate greater levels of depressive mood. Scoring is categorized as follows:

0–4 points: Normal,

5–8 points: Mild depressive symptoms,

9–11 points: Moderate depressive symptoms,

≥12 points: Severe depressive symptoms.

Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS):

The GAS is a self-report tool designed to assess anxiety symptoms in the elderly population. It evaluates three subdomains: somatic, cognitive, and emotional [

20]. The Turkish version consists of 28 items, with the first 23 items contributing to the total score. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale: "Never (0)," "Sometimes (1)," "Often (2)," and "Always (3)." Items 24–28 are used by clinicians to determine the domain of anxiety but are not included in the total score. Participants are asked to reflect on their symptoms over the past week. The total score ranges from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety.

Radiological Imaging Findings

All scans were performed on 1.5 T MRI units (GE Signa Explorer; GE, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Non-contrast T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and FLAIR sequences were obtained. The imaging parameters were as follows: axial and sagittal T1-weighted MRI (TR/TE: 543/24 ms), axial and coronal T2-weighted MRI (TR/TE: 5724/102 ms), and axial FLAIR images (TR/TE: 8000/86 ms). The neurology expert (SND) performed all assessments blinded to patient demographic and clinical data.

Koedam, medial temporal atrophy (MTA), orbitofrontal cortex grading, and Fazekas scores were evaluated by a single neuroradiologist (NHS) with over five years of clinical experience. Lesions were analyzed in terms of their location (juxtacortical, periventricular, and deep brain structures), subcortical atrophy, and lesion burden using the Fazekas grading system:

Fazekas 0: No lesions or a single punctate lesion (white matter hyperintensity).

Fazekas 1: Multiple punctate lesions.

Fazekas 2: Beginning to coalesce lesions (bridging).

Fazekas 3: Large, confluent lesions.

Subcortical atrophy was calculated using the ventricle-to-brain ratio, without differentiating white and gray matter. Lesions in white matter adjacent to the cortex were classified as juxtacortical, while signal abnormalities extending up to 5 mm from the ventricles to the cortex were categorized as periventricular.

MTA Score

The medial temporal atrophy (MTA) score was qualitatively evaluated based on the degree of atrophy in the choroid fissure, temporal horn, and hippocampal volume, following the criteria described by Frisoni et al. [

21]:

MTA 0: Normal choroid fissure, temporal horn, and hippocampal volume.

MTA 1: Mildly enlarged choroid fissure.

MTA 2: Moderately enlarged choroid fissure, with mild enlargement of the temporal horn and mild reduction in hippocampal volume.

MTA 3: Significantly enlarged choroid fissure, with moderate enlargement of the temporal horn and moderate reduction in hippocampal volume.

MTA 4: Severely enlarged choroid fissure, significant enlargement of the temporal horn, and marked reduction in hippocampal volume [

22,

23].

Koedam Score

Parietal atrophy was qualitatively assessed using the Koedam score, based on the degree of atrophy in the parietal region in the sagittal plane, as described by Koedam et al. [

24]:

Koedam 0: No sulcal widening or precuneus atrophy.

Koedam 1: Mild sulcal widening and mild precuneus atrophy.

Koedam 2: Marked sulcal widening and moderate parietal cortical atrophy.

Koedam 3: Severe parietal atrophy with a "knife-edge" sulcal appearance [

25].

Orbitofrontal Grading

Orbitofrontal atrophy was graded on a scale from 0 (no atrophy) to 4 (severe atrophy) based on established criteria [

26].

MRIs affected by motion artifacts caused by patient movement during scanning were deemed unsuitable and excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Frequency analysis was conducted to examine the demographic characteristics of the study participants. Subsequently, scores for the subdimensions and total dimensions of the measurement tools were calculated, and descriptive statistics for these scores were presented. Average comparison tests were performed to analyze the subdimension and overall scores of the scales in relation to specific participant characteristics.

Before performing comparisons, the skewness and kurtosis values of the variables were checked to ensure they fell between -3 and +3, confirming the normality of the distribution. Descriptive statistics for numerical variables were reported as mean (Mean), standard deviation (SD), median (Med.), minimum (Min.), and maximum (Max.) values.

A statistical significance level of p < 0.05 was considered in all analyses. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 27.

Results

The frequency analysis results for the descriptive characteristics of the participants are summarized as follows. A total of 200 dementia patients (110 women) and 100 healthy volunteers (HV) (60 women) participated in the study. The mean age of the patient group was 71.31 ± 11.71 years, while the mean age of the HV group was 68 ± 3.5 years.

In terms of education levels, 146 participants (48.67%) had 0–5 years of education, 105 participants (35%) had 6–11 years of education, and 49 participants (16.33%) had 12 or more years of education. The years of education of healthy volunteers and patients were selected to be similar to each other.

The distribution of participants by diagnosis showed that 94 patients (47%) were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), 30 patients (15%) with Vascular Dementia (VD), 30 patients (15%) with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), 26 patients (13%) with Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), and 20 patients (10%) with Lewy Body Dementia (LBD).

In terms of disease duration, 135 patients (67.5%) had a disease duration of 1–3 years, 38 patients (19%) had a duration of 3–5 years, and 27 patients (13.5%) had a disease duration of 5 years or more.

The prevalence of apathy in the patient group was calculated as 88.24%.

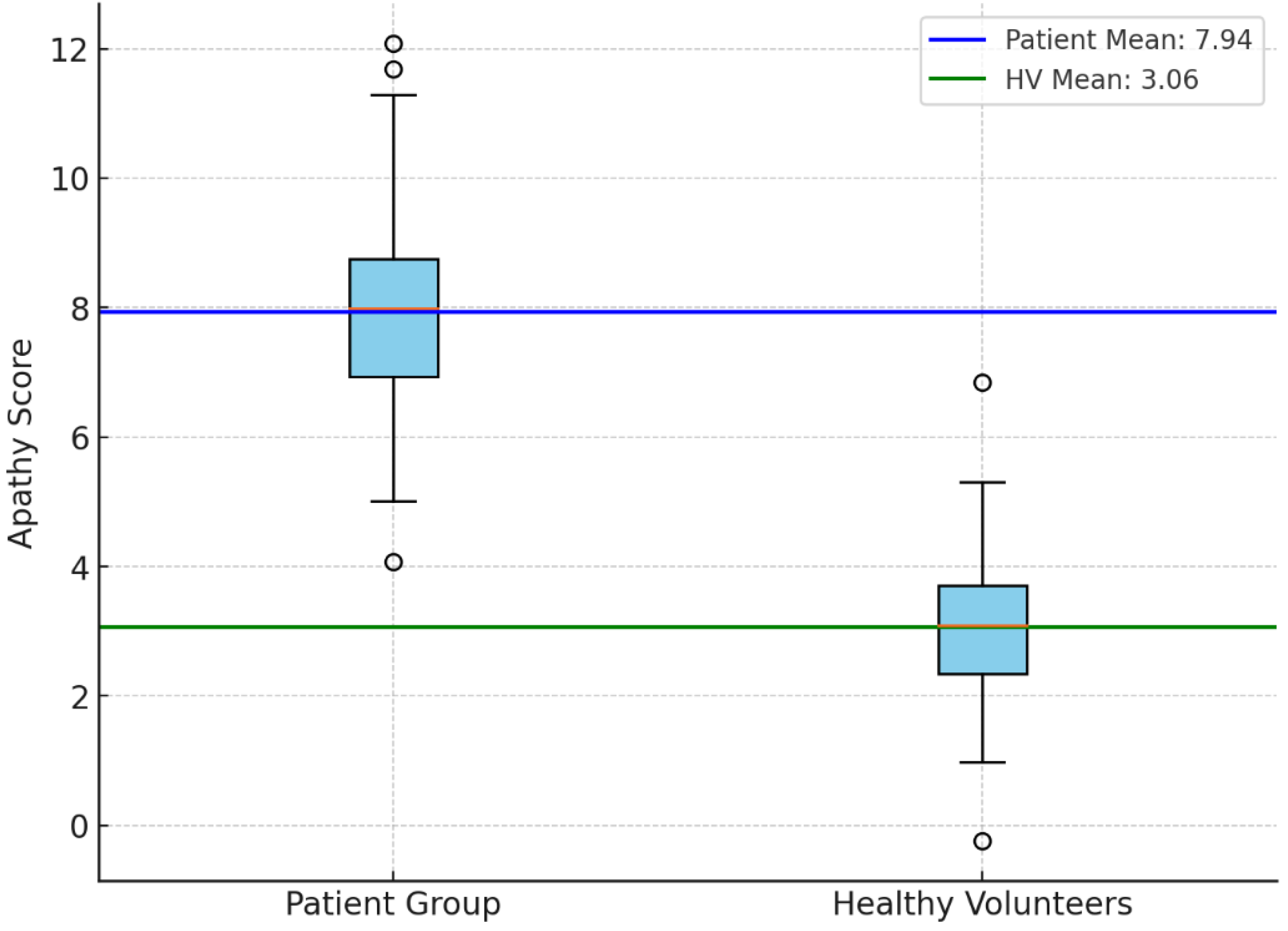

An independent samples t-test was performed to compare the apathy evaluation scores between the patient group and the healthy volunteer (HV) group. The results revealed a statistically significant difference, with the patient group exhibiting higher apathy scores compared to the HV group (t = 9.69, p < 0.001; p-value: 1.54e-17) (

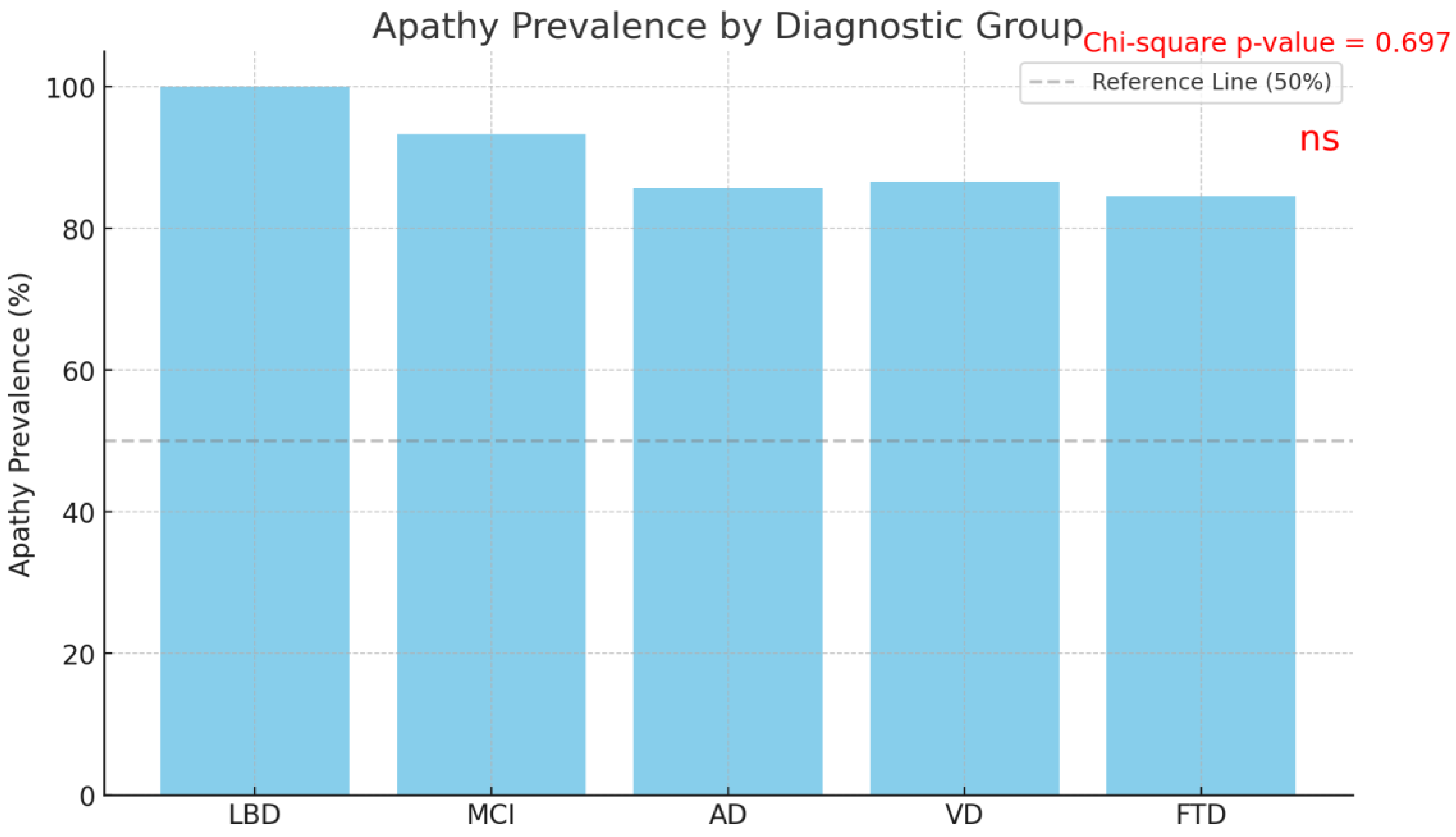

Figure 1). When the prevalence of apathy was analyzed by diagnosis, the rates were found to be 100.0% in Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), 93.33% in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), 85.71% in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), 86.67% in Vascular Dementia (VD), and 84.62% in Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD).

The Chi-square test conducted to compare the prevalence of apathy among diagnostic groups revealed no statistically significant difference (χ² = 2.21, p = 0.697) (

Figure 2). Similarly, Chi-square and t-test analyses demonstrated no statistically significant relationships between the presence of apathy and gender (p = 0.617), age (p = 0.463), education duration (p = 0.716), or disease onset year (p = 0.067).

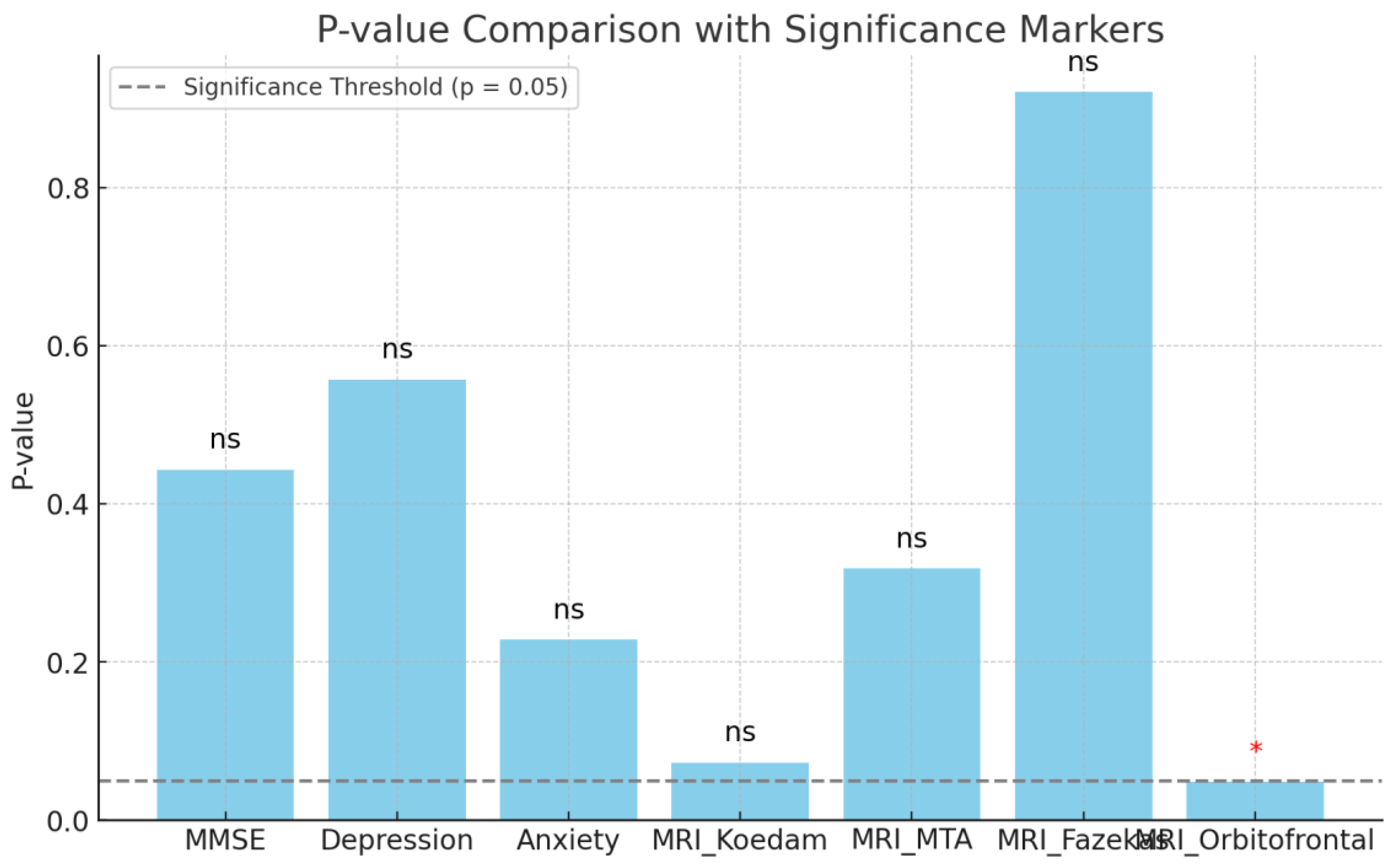

Additionally, comparison tests showed no statistically significant associations between the presence of apathy and cognitive status, as assessed by the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (p = 0.505 and p = 0.443, respectively). No significant relationships were observed between apathy and depression (p = 0.557) or anxiety (p = 0.228) (

Figure 3).

The analysis examining the relationship between the presence of apathy and MRI atrophy scales found no significant differences for the Koedam scale (t = -1.94, p = 0.073), MTA scale (t = -1.04, p = 0.318), or Fazekas scale (t = -0.10, p = 0.921). However, a significant difference was observed between the apathetic and non-apathetic groups on the Orbitofrontal Sulcus Scale (t = -2.18, p = 0.048) (

Figure 3).

Discussion

This study investigated the frequency of apathy in dementia patients, differences in the presence of apathy among various types of dementia, its relationship with cognitive function and other neuropsychiatric symptoms, and its association with MRI findings.

The prevalence of apathy in dementia varies widely in the literature. A review reported prevalence ranges of 26–82% for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), 28.6–91.7% for Vascular Dementia (VaD), and 54.8–88.0% for Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) [

29]. In some studies, the overall prevalence across all dementia types has been reported as 36% [

27]. In the present study, the frequency of apathy in the patient group was calculated as 88.24%. When analyzed by specific diagnoses, the prevalence of apathy was 100.0% in Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), 93.33% in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), 85.71% in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), 86.67% in Vascular Dementia (VD), and 84.62% in Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD). Variations in prevalence rates reported in the literature may stem from differences in the tools and criteria used to assess apathy.

In studies comparing Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), apathy has generally been observed more frequently in FTD [

30]. However, contrary to our hypothesis, no significant differences in the frequency of apathy were found among the dementia types in this study.

Although long-term follow-up studies suggest that apathy may increase over time, no significant differences were observed in our study regarding the years since the onset of dementia [

31].

The relationship between apathy and depression is frequently discussed in the literature, with publications often focusing on their coexistence or their predictive value for dementia. While some studies suggest an overlap between apathy and depression, these are distinct symptoms. In our study, no significant relationship was found between apathy and depression [

32]. Regarding their predictive value for dementia, particularly in Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) patients, long-term monitoring is required.

An increase in the frequency of apathy is generally expected with cognitive decline [

33].

Imaging studies have consistently shown the strongest association with apathy in the orbitofrontal cortex [

34]. In our study, among the atrophy regions evaluated, a significant relationship was found only with the orbitofrontal sulcus, which reflects orbitofrontal cortex atrophy. This finding is particularly important in settings where access to functional imaging devices is limited, as structural MRI may provide supportive evidence for the presence of this symptom.

Some studies have suggested that white matter changes are associated with apathy and may serve as a predictor of dementia, particularly in cases involving small vessel disease [

35,

36]. However, in our study, no significant association was observed between apathy and the Fazekas classification, which assesses white matter changes.

Strengths of the Study

This study encompasses multiple types of dementia, which is a significant strength as it allows for comparisons of apathy and other neuropsychiatric symptoms across dementia subtypes, thereby contributing to the existing body of knowledge. Such comprehensive analyses help address gaps in the literature.

In addition to apathy, the study evaluated other neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression and anxiety. This provides a more detailed understanding of the neuropsychiatric profiles of dementia patients and paves the way for more targeted interventions aimed at improving patient management.

Another notable strength of the study is its investigation of the relationships between apathy, neuropsychiatric symptoms, cognitive functions, and cranial imaging findings. The use of structural MRI, a widely accessible imaging modality, enhances the practical applicability of the study’s findings.

Finally, the exploration of connections between cognitive assessments and neurological structures offers valuable insights into the neurobiological basis of dementia, thereby advancing our understanding of the disease.

Weaknesses of the Study

This study was conducted at a single hospital’s dementia clinic, which may limit the generalizability of its findings. Additionally, the retrospective and cross-sectional design represents another limitation. Longitudinal follow-up studies are needed to provide more comprehensive insights into the mechanisms underlying the occurrence of apathy in dementia.

Conclusions

Apathy is a highly prevalent symptom in dementia, including in its prodromal stages. This study contributes significantly to the literature by demonstrating a relationship between apathy and orbitofrontal sulcus atrophy. The absence of differences in apathy prevalence among dementia subtypes highlights the need for further research into the neurobiological origins of this symptom. Apathy may serve as an important marker for facilitating the early diagnosis of dementia.

However, the retrospective design and single-center data limit the generalizability of the findings. To validate these results, multicenter, longitudinal studies are recommended.

Recommendations for Future Studies

To better understand the effects of apathy on the dementia process and its long-term impact on prognosis, longitudinal studies are recommended. Such studies could clarify the role of apathy in transitions between different stages of dementia. Incorporating biomarker evaluations would provide deeper insights into the underlying biological mechanisms.

Conducting a multicenter study with a larger and more diverse population would improve the generalizability of the findings. This approach would offer more comprehensive data on the prevalence of apathy and its relationship with dementia subtypes, contributing to a broader understanding of its universal applicability.

Author Contributions

Concept - OT; Design - OT, ŞŞ; Supervision - ŞŞ; Resources - OT, ŞŞ; Materials - OT; Data Collection and/or Processing - OT; Analysis and/or Interpretation - ŞŞ; Literature Search - OT; Writing Manuscript - OT; Critical Review - OT, ŞŞ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article received no financial support.

Ethics Committee Approval

University of Health Sciences, Hamidiye Faculty of Medicine, Sancaktepe Sehit Prof. Dr. Ilhan Varank SUAM Ethics Committee granted approval for this study (date: 20.02.2024, number: 2024/30).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants involved in the study, and consent forms were signed by the parents of all participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants involved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Q.F.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Jiang, T.; Tan, M.S.; Tan, L.; et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016, 190, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegri, R.F.; Sarasola, D.; Serrano, C.M.; Taragano, F.E.; Arizaga, R.L.; Butman, J.; et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as a predictor of caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006, 2, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong, S.; Irish, M.; Husain, M.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O.; Kumfor, F. Apathy and its impact on carer burden and psychological wellbeing in primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol Sci. 2020, 416, 117007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyketsos, C.G.; Carrillo, M.C.; Ryan, J.M.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Trzepacz, P.; Amatniek, J.; et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2011, 7, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimo, S.; Santangelo, G.; D’Iorio, A.; Trojano, L.; Grossi, D. Neural correlates of apathy in patients with neurodegenerative disorders: an activation likelihood estimation (ALE) meta-analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019, 13, 1815–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, P.; Lanctôt, K.L.; Agüera-Ortiz, L.; Aalten, P.; Bremond, F.; Defrancesco, M.; et al. Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. Eur Psychiatry J Assoc Eur Psychiatr. 2018, 54, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafarikas, N.; Selbaek, G.; Fladby, T.; Šaltytė Benth, J.; Auning, E.; Aarsland, D. Frequency and subgroups of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and different stages of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018, 30, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresnais, D.; Humble, M.B.; Bejerot, S.; Meehan, A.D.; Fure, B. Apathy as a Predictor for Conversion From Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2023, 36, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dalen, J.W.; Van Wanrooij, L.L.; Moll van Charante, E.P.; Richard, E.; van Gool, W.A. Apathy is associated with incident dementia in community-dwelling older people. Neurology. 2018, 90, e82–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascovsky, K.; Hodges, J.R.; Knopman, D.; Mendez, M.F.; Kramer, J.H.; Neuhaus, J.; et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain J Neurol. 2011, 134 Pt 9, 2456–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, P.; Kalaria, R.; O’Brien, J.; Skoog, I.; Alladi, S.; Black, S.E.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for vascular cognitive disorders: a VASCOG statement. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014, 28, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.P.; Weintraub, D.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güngen, C.; Ertan, T.; Eker, E.; Yaşar, R.; Engin, F. Reliability and validity of the standardized Mini Mental State Examination in the diagnosis of mild dementia in Turkish population. Turk Psikiyatri Derg Turk J Psychiatry. 2002, 13, 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mioshi, E.; Dawson, K.; Mitchell, J.; Arnold, R.; Hodges, J.R. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): a brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006, 21, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gürv, H.; Baran, B. Demanslar ve Kognitif Bozukluklarda Ölçekler.

- Marin, R.S.; Biedrzycki, R.C.; Firinciogullari, S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991, 38, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pifer, M.A.; Segal, D.L. Geriatric Anxiety Scale: Development and Preliminary Validation of a Long-Term Care Anxiety Assessment Measure. Clin Gerontol. 2020, 43, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoni, G.B.; Scheltens P h Galluzzi, S.; Nobili, F.M.; Fox, N.C.; Robert, P.H.; et al. Neuroimaging tools to rate regional atrophy, subcortical cerebrovascular disease, and regional cerebral blood flow and metabolism: consensus paper of the EADC. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003, 74, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlund, L.O.; Westman, E.; van Westen, D.; Wallin, A.; Shams, S.; Cavallin, L.; et al. Imaging biomarkers of dementia: recommended visual rating scales with teaching cases. Insights Imaging. 2017, 8, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtner, J.; Prayer, D. Neuroimaging in dementia. Wien Med Wochenschr 1946. 2021, 171, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koedam, E.L.G.E.; Lehmann, M.; van der Flier, W.M.; Scheltens, P.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Fox, N.; et al. Visual assessment of posterior atrophy development of a MRI rating scale. Eur Radiol. 2011, 21, 2618–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo Rodríguez, L.; Tovar Salazar, D.J.; Fernández García, N.; Pastor Hernández, L.; Fernández Guinea, Ó. Magnetic resonance imaging in dementia. Radiologia. 2018, 60, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, L.; Fumagalli, G.G.; Barkhof, F.; Scheltens, P.; O’Brien, J.T.; Bouwman, F.; et al. MRI visual rating scales in the diagnosis of dementia: evaluation in 184 post-mortem confirmed cases. Brain J Neurol. 2016, 139, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyketsos, C.G.; Lopez, O.; Jones, B.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Breitner, J.; DeKosky, S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002, 288, 1475–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, T.W.; Miller, B.L.; Boone, K.; Mishkin, F.; Cummings, J.L. Frontotemporal dementia classification and neuropsychiatry. The Neurologist. 2002, 8, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrotta, I.; Cacciatore, S.; D’Andrea, F.; D’Anna, M.; Giancaterino, G.; Lazzaro, G.; et al. Prevalence, treatment, and neural correlates of apathy in different forms of dementia: a narrative review. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol. 2024, 45, 1343–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.G.; Rademaker, A.W.; Bigio, E.H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Weintraub, S. Apathy and Disinhibition Related to Neuropathology in Amnestic Versus Behavioral Dementias. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2019, 34, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, R.; Zuidema, S.; Jansen, I.; Verhey, F.; Koopmans, R. Course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in residents with dementia in long-term care institutions: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 1040–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkstein, S.E.; Ingram, L.; Garau, M.L.; Mizrahi, R. On the overlap between apathy and depression in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005, 76, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deardorff, W.J.; Grossberg, G.T. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer’s dementia and vascular dementia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019, 165, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tunnard, C.; Whitehead, D.; Hurt, C.; Wahlund, L.O.; Mecocci, P.; Tsolaki, M.; et al. Apathy and cortical atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011, 26, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, J.; Tuladhar, A.M.; Hollocks, M.J.; Brookes, R.L.; Tozer, D.J.; Barrick, T.R.; et al. Apathy is associated with large-scale white matter network disruption in small vessel disease. Neurology. 2019, 92, e1157–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.; Edman, A.; Lind, K.; Rolstad, S.; Sjögren, M.; Wallin, A. Apathy is a prominent neuropsychiatric feature of radiological white-matter changes in patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010, 25, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).