Submitted:

28 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

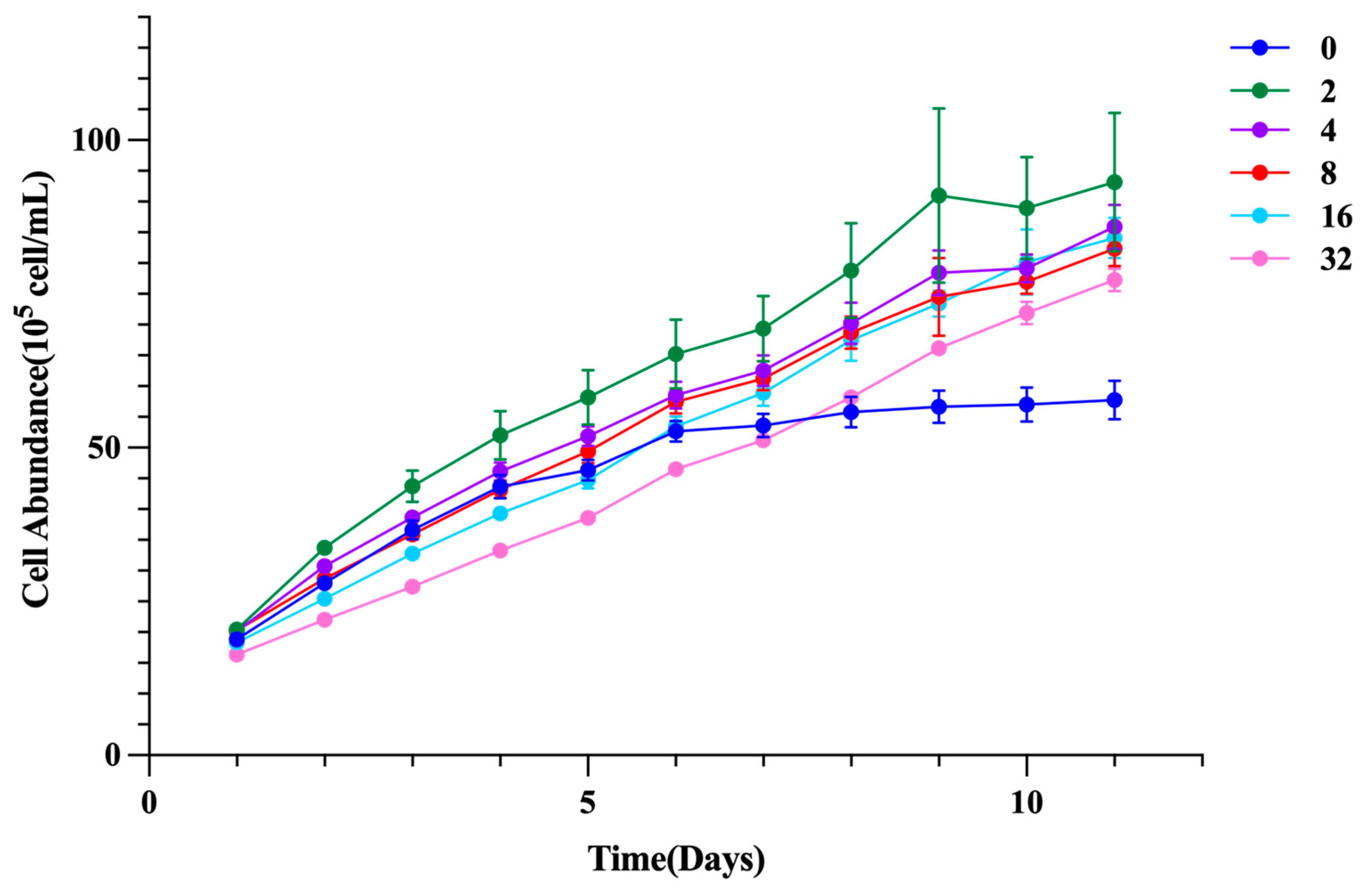

2.1. Effects of Glycine Concentration on the Growth of I. zhanjiangensis

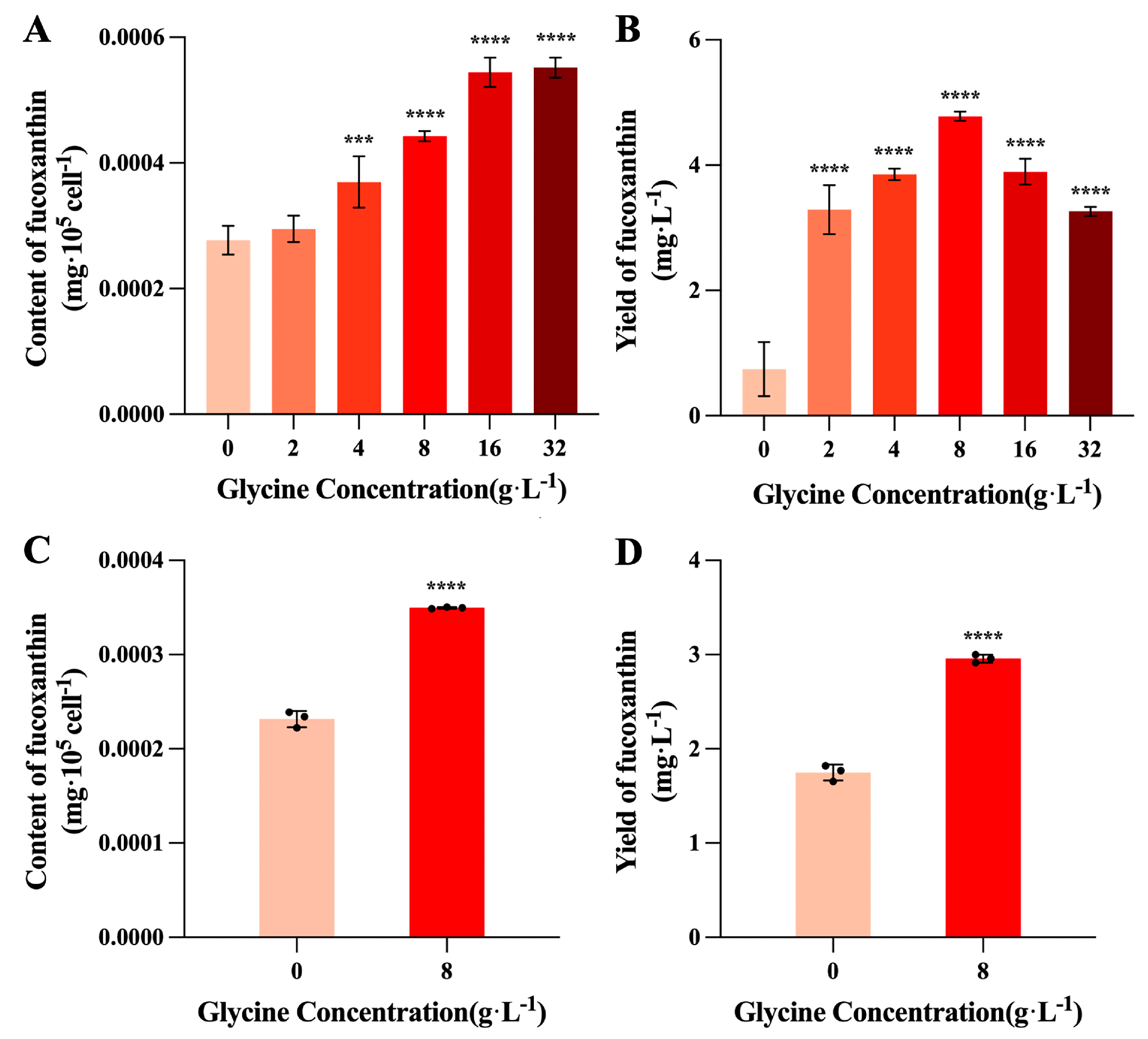

2.2. Effects of Glycine Concentration on Fucoxanthin Content and Yield in I. zhanjiangensis

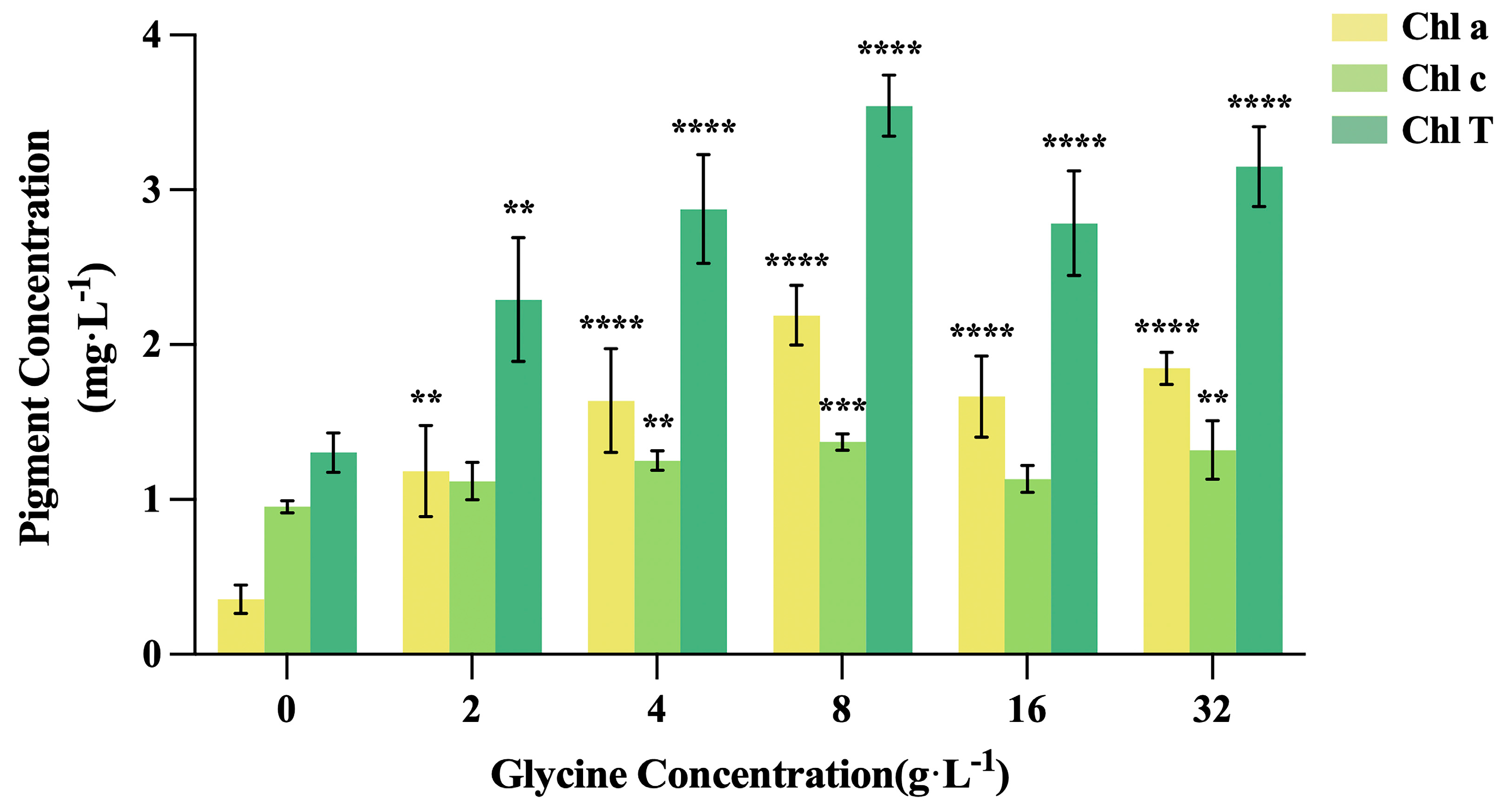

2.3. Effects of Glycine Concentrations on Chlorophyll Concentration in I. zhanjiangensis

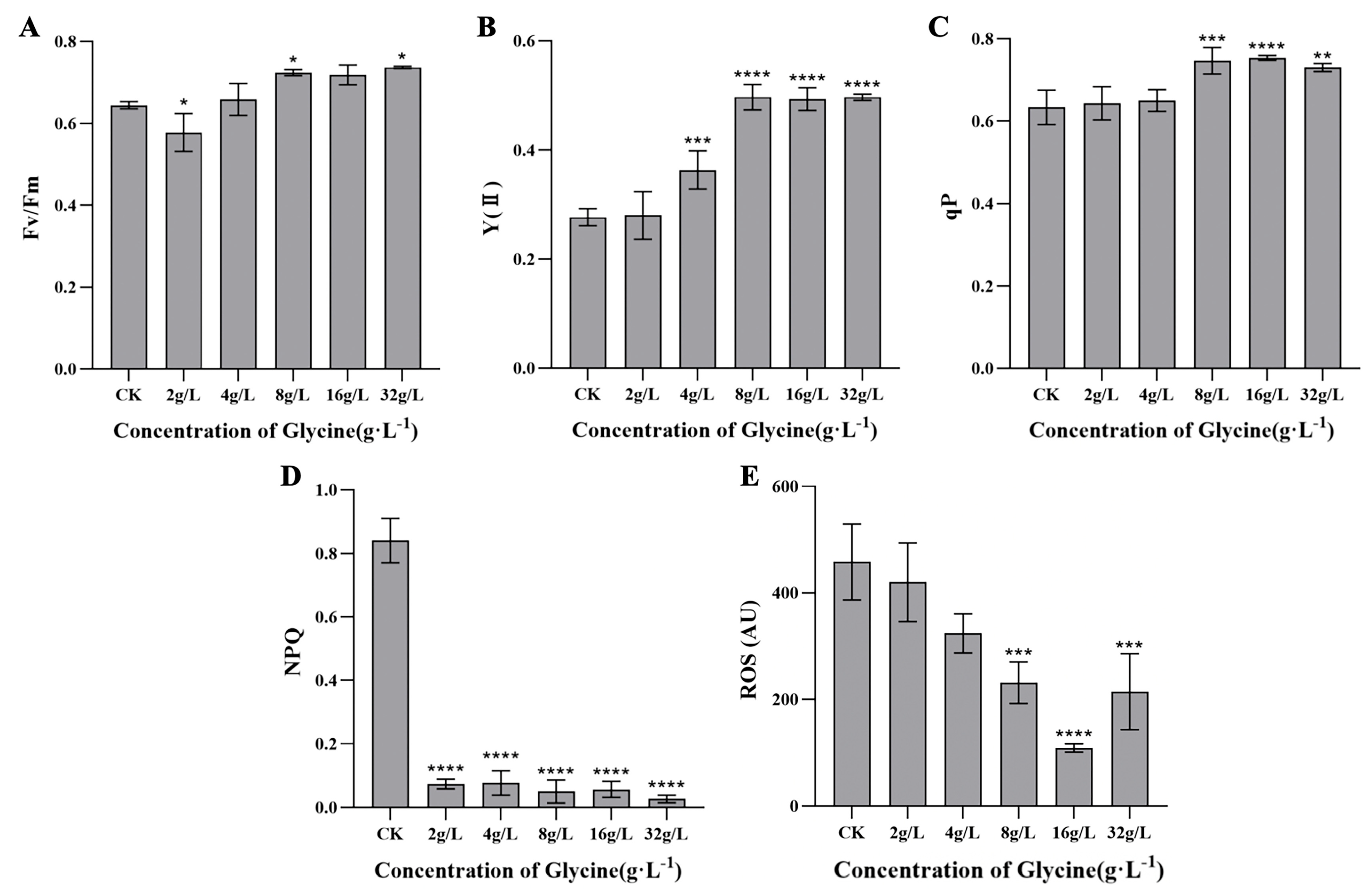

2.4. Effects of Glycine Concentrations on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters and ROS Levels in I. zhanjiangensis

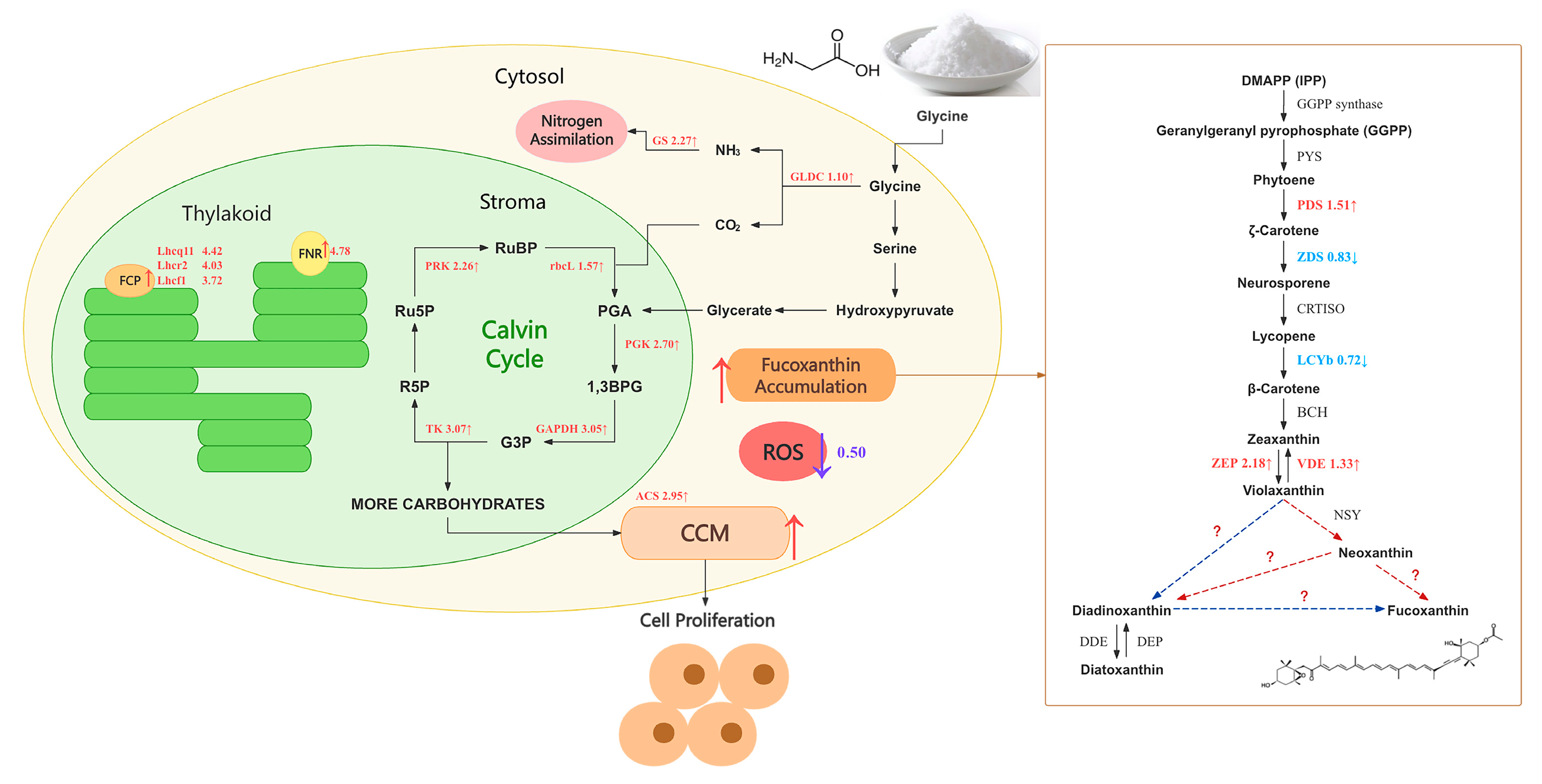

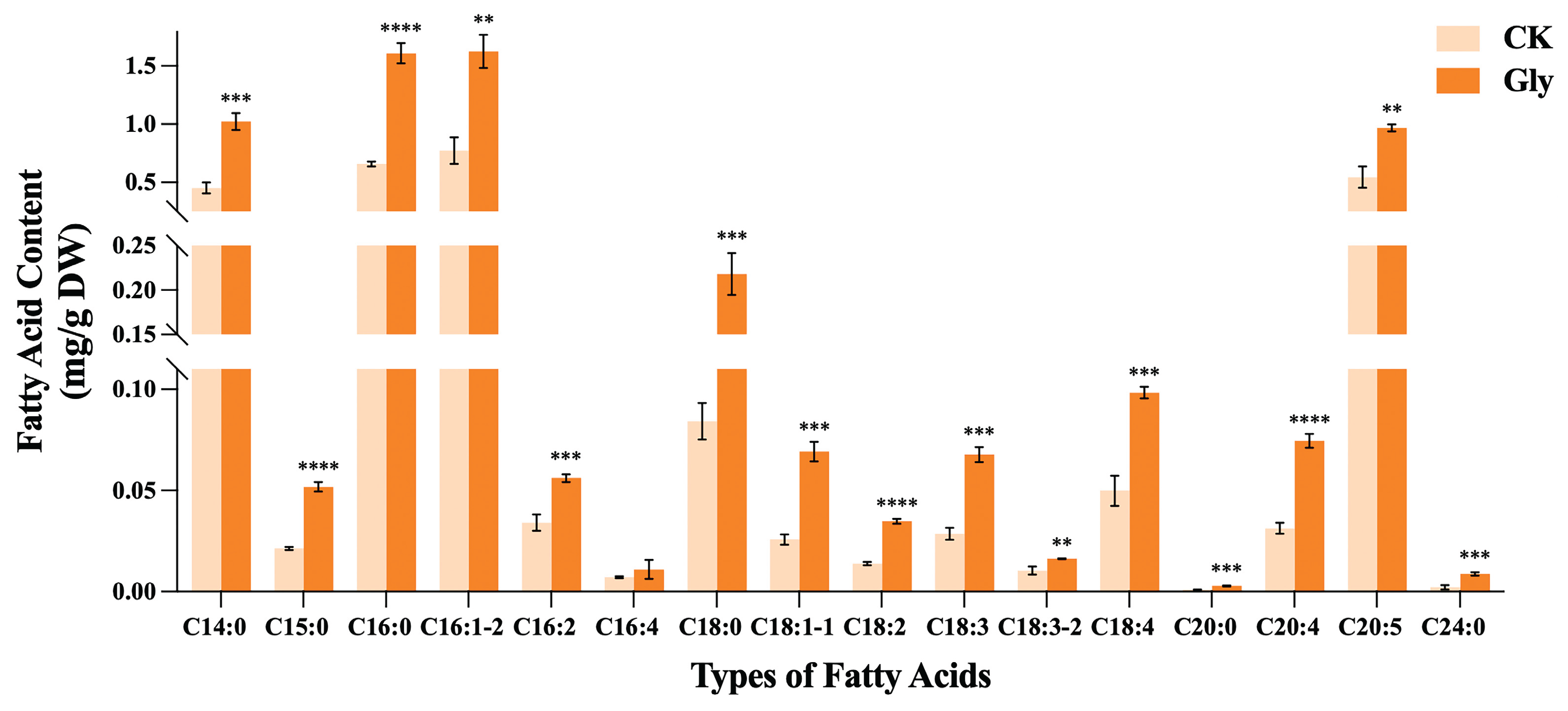

2.5. Potential Mechanisms of Glycine Affecting Cell Proliferation and Fucoxanthin Synthesis in I. zhanjiangensis

3. Discussion

3.1. Glycine Significantly Promotes the Accumulation of Biomass in I. zhanjiangensis

3.2. Glycine Induces the Production of Fucoxanthin in Algae Through Carbon and Nitrogen Supplementation

3.3. Glycine Promotes the Synthesis of Chlorophyll as a Nitrogen Source

3.4. Glycine Enhances the Photosynthetic Activity of I. zhanjiangensis

3.5. Potential Mechanisms by Which Glycine Affects Cell Proliferation and Fucoxanthin Synthesis in I. zhanjiangensis

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Algal Strains and Culture Conditions

4.2. Determination of Cell Parameters

4.3. Determination of Fucoxanthin Content and Yield

4.4. Determination of Fucoxanthin Content and Yield in Scaled-Up Cultures

4.5. Effects of Glycine on Photosynthetic Parameters in I. zhanjiangensis

4.5.1. Determination of Chlorophyll Content

4.5.2. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

4.6. Determination of ROS Content

4.7. Transcriptome Assay

4.8. Esterification and Analysis of Fatty Acids

4.9. Data Statistics and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acetyl-CoA Synthetase |

| BCH | β-Carotene Hydroxylase |

| CCM | Central Carbon Metabolism |

| CRTISO | Carotenoid Isomerase |

| DDE | Diadinoxanthin De-epoxidase |

| DEP | Diatoxanthin Epoxidase |

| DMAPP | Dimethylallyl Pyrophosphate |

| FCP | Fucoxanthin-Chlorophyll a/c-binding Protein |

| FNR | Ferredoxin–NADP+ Reductase |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| GCS | Glycine Cleavage System |

| GLDC | Glycine Decarboxylase |

| GS | Glutamine Synthetase |

| IPP | Isopentenyl Pyrophosphate |

| LCYb | Lycopene β-Cyclase |

| Lhcr, Lhcf, Lhcq | Fucoxanthin-Chlorophyll a/c-binding Protein subfamilies |

| NSY | Neoxanthin Synthase |

| PDS | Phytoene Desaturase |

| PGK | Phosphoglycerate Kinase |

| PRK | Phosphoribulokinase |

| PYS | Phytoene Synthase |

| rbcL | Rubisco Large Subunit |

| TK | Transketolase |

| VDE | Violaxanthin De-epoxidase |

| ZDS | ζ-Carotene Desaturase |

| ZEP | Zeaxanthin Epoxidase |

References

- Peng, J.; Yuan, J.-P.; Wu, C.-F.; Wang, J.-H. Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid present in brown seaweeds and diatoms: Metabolism and bioactivities relevant to human health. Marine drugs 2011, 9, 1806–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammone, M.A.; D’Orazio, N. Anti-obesity activity of the marine carotenoid fucoxanthin. Marine drugs 2015, 13, 2196–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, K. Function of marine carotenoids. Food factors for health promotion 2009, 61, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, T.; Kikuchi, M.; Kubodera, A.; Kawakami, Y. Proton-donative antioxidant activity of fucoxanthin with 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). IUBMB Life 1997, 42, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; He, Y. Analysis and Identification of Major Carotenoids in Isochrysis zhanjiangensis. Journal of Food Safety & Quality 2018, 9, 1901–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Lü, S.; Liu, H. A New Species of the Genus Isochrysis (Isochrysidales)—Isochrysis zhanjiangensis sp. nov. and Observations on Its Ultrastructure. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 2007, 29, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, F.; Manyakhin, A.Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Ge, B.; Yan, X.; Ruan, R. The influence of spermidine on the build-up of fucoxanthin in Isochrysis sp. Acclimated to varying light intensities. Bioresource Technology 2023, 387, 129688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcıa, M.C.; Mirón, A.S.; Sevilla, J.F.; Grima, E.M.; Camacho, F.G. Mixotrophic growth of the microalga Phaeodactylum tricornutum: influence of different nitrogen and organic carbon sources on productivity and biomass composition. Process Biochemistry 2005, 40, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ano, A.; Funahashi, H.; Nakao, K.; Nishizawa, Y. Effect of glycine on 5-aminolevulinic acid biosynthesis in heterotrophic culture of Chlorella regularis YA-603. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 1999, 88, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Liu, B.; Yang, B.; Sun, P.; Lu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, F. Screening of diatom strains and characterization of Cyclotella cryptica as a potential fucoxanthin producer. Marine Drugs 2016, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Sun, H.; Zhao, W.; Cheng, K.-W.; Chen, F.; Liu, B. A hetero-photoautotrophic two-stage cultivation process for production of fucoxanthin by the marine diatom Nitzschia laevis. Marine Drugs 2018, 16, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, N.A.; Sanders, J.P.; Bruins, M.E. Solubility of the proteinogenic α-amino acids in water, ethanol, and ethanol–water mixtures. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 2018, 63, 488–497. [Google Scholar]

- Neilson, A.; Lewin, R. The uptake and utilization of organic carbon by algae: an essay in comparative biochemistry. Phycologia 1974, 13, 227–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Duan, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Z. Effects of Organic Carbon Compounds on the Growth of Isochrysis zhanjiangensis. Ecological Sciences 2007, 26, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berland, B.; Bonin, D.; Guerin-Ancey, O.; Antia, N. Concentration requirement of glycine as nitrogen source for supporting effective growth of certain marine microplanktonic algae. Marine biology 1979, 55, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, W.A.; AbdElgawad, H.; Essawy, E.A.; Tawfik, E.; Abdelhameed, M.S.; Hammouda, O.; Korany, S.M.; Elsayed, K.N. Glycine differentially improved the growth and biochemical composition of Synechocystis sp. PAK13 and Chlorella variabilis DT025. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023, 11, 1161911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Feng, L.; Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Hassani, D.; Huang, D. Effect of glycine nitrogen on lettuce growth under soilless culture: A metabolomics approach to identify the main changes occurred in plant primary and secondary metabolism. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 98, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhong, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Sajid, H.; Wu, L.; Jin, Q. Glycine increases cold tolerance in rice via the regulation of N uptake, physiological characteristics, and photosynthesis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2017, 112, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Wang, C.-L.; He, W.-P.; Qu, Y.-Z.; Li, Y.-S. Photosynthetic characteristics and effects of exogenous glycine of Chorispora bungeana under drought stress. Photosynthetica 2016, 54, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.; Wu, H.; Lu, B.; Luo, X.; Gong, C.; Bai, J. Low concentrations of glycine inhibit photorespiration and enhance the net rate of photosynthesis in Caragana korshinskii. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, Y. Identification of Potential Factors for the Promotion of Fucoxanthin Synthesis by Methyl Jasmonic Acid Treatment of Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Marine Drugs 2023, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cai, X.; Gu, W.; Wang, G. Transcriptome analysis of carotenoid biosynthesis in Dunaliella salina under red and blue light. Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 2020, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, T.; Padhan, J.K.; Kumar, P.; Sood, H.; Chauhan, R.S. Comparative transcriptomics uncovers differences in photoautotrophic versus photoheterotrophic modes of nutrition in relation to secondary metabolites biosynthesis in Swertia chirayita. Molecular biology reports 2018, 45, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Muthuraj, M.; Palabhanvi, B.; Ghoshal, A.K.; Das, D. High cell density lipid rich cultivation of a novel microalgal isolate Chlorella sorokiniana FC6 IITG in a single-stage fed-batch mode under mixotrophic condition. Bioresource technology 2014, 170, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthuraj, M.; Kumar, V.; Palabhanvi, B.; Das, D. Evaluation of indigenous microalgal isolate Chlorella sp. FC2 IITG as a cell factory for biodiesel production and scale up in outdoor conditions. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2014, 41, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, S. Effects of various amino acids as organic nitrogen sources on the growth and biochemical composition of Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Bioresource technology 2015, 197, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Mujtaba, G.; Lee, K. Effects of nitrogen sources on cell growth and biochemical composition of marine chlorophyte Tetraselmis sp. for lipid production. Algae 2016, 31, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Li, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, X. Research Progress on Photorespiration. Journal of Tropical and Subtropical Botany 2022, 30, 782–790. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, K.; Jokinen, M.; Canvin, D.T. Reduction of nitrate via a dicarboxylate shuttle in a reconstituted system of supernatant and mitochondria from spinach leaves. Plant Physiology 1980, 65, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tang, H.; Ma, H.; Holland, T.C.; Ng, K.S.; Salley, S.O. Effect of nutrients on growth and lipid accumulation in the green algae Dunaliella tertiolecta. Bioresource technology 2011, 102, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamoto, A.; Kato, Y.; Yoshida, E.; Hasunuma, T.; Kondo, A. Development of a method for fucoxanthin production using the Haptophyte marine microalga Pavlova sp. OPMS 30543. Marine Biotechnology 2021, 23, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Liu, B.; He, Y.; Guo, B.; Sun, H.; Chen, F. Novel insights into mixotrophic cultivation of Nitzschia laevis for co-production of fucoxanthin and eicosapentaenoic acid. Bioresource Technology 2019, 294, 122145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premaratne, M.; Liyanaarachchi, V.C.; Nimarshana, P.; Ariyadasa, T.U.; Malik, A.; Attalage, R.A. Co-production of fucoxanthin, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and bioethanol from the marine microalga Tisochrysis lutea. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2021, 176, 108160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, W.; Liu, T. Combined production of fucoxanthin and EPA from two diatom strains Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Cylindrotheca fusiformis cultures. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering 2018, 41, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wang, K.; Wan, L.; Li, A.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, C. Production, characterization, and antioxidant activity of fucoxanthin from the marine diatom Odontella aurita. Marine drugs 2013, 11, 2667–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durnford, D.; Deane, J.; Tan, S.; McFadden, G.; Gantt, E.; Green, B. A phylogenetic assessment of the eukaryotic light-harvesting antenna proteins, with implications for plastid evolution. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1999, 48, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Gao, B.; Fu, J.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, C. Production of fucoxanthin, chrysolaminarin, and eicosapentaenoic acid by Odontella aurita under different nitrogen supply regimes. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2018, 126, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.Q.; Park, Y.J.; Winarto, J.; Huynh, P.K.; Moon, J.; Choi, Y.B.; Song, D.-G.; Koo, S.Y.; Kim, S.M. Understanding the Impact of Nitrogen Availability: A Limiting Factor for Enhancing Fucoxanthin Productivity in Microalgae Cultivation. Marine Drugs 2024, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajot, A.; Lavaud, J.; Carrier, G.; Garnier, M.; Saint-Jean, B.; Rabilloud, N.; Baroukh, C.; Bérard, J.-B.; Bernard, O.; Marchal, L. The fucoxanthin chlorophyll a/c-binding protein in tisochrysis lutea: influence of nitrogen and light on fucoxanthin and chlorophyll a/c-binding protein gene expression and fucoxanthin synthesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 830069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ördög, V.; Stirk, W.A.; Bálint, P.; van Staden, J.; Lovász, C. Changes in lipid, protein and pigment concentrations in nitrogen-stressed Chlorella minutissima cultures. Journal of Applied Phycology 2012, 24, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berges, J.A.; Charlebois, D.O.; Mauzerall, D.C.; Falkowski, P.G. Differential effects of nitrogen limitation on photosynthetic efficiency of photosystems I and II in microalgae. Plant Physiology 1996, 110, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, T.; Angun, P.; Demiray, Y.E.; Ozkan, A.D.; Elibol, Z.; Tekinay, T. Differential effects of nitrogen and sulfur deprivation on growth and biodiesel feedstock production of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biotechnology and bioengineering 2012, 109, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, I.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, G.; Song, X.; Hussein Ibrahim, M.E.; Ibrahim Salih, E.G. Effect of N on growth, antioxidant capacity, and chlorophyll content of sorghum. Agronomy 2022, 12, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.K.; Han, X.; Lin, E.; Norton, R.; Chen, D. Does elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration increase wheat nitrogen demand and recovery of nitrogen applied at stem elongation? Agriculture, ecosystems & environment 2012, 155, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Badran, E.G.; Abogadallah, G.M.; Nada, R.M.; Nemat Alla, M.M. Role of glycine in improving the ionic and ROS homeostasis during NaCl stress in wheat. Protoplasma 2015, 252, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Hong, H.; Li, W.-C.; Yang, L.; Huang, J.; Xiao, Y.-L.; Chen, X.-Y.; Chen, G.-Y. Downregulation of rubisco activity by non-enzymatic acetylation of RbcL. Molecular plant 2016, 9, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Walker, B.J. Photorespiratory glycine contributes to photosynthetic induction during low to high light transition. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 19365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Wu, T.; Lu, X.; Chu, Y.; Chen, F. Integrated metabolic tools reveal carbon alternative in Isochrysis zhangjiangensis for fucoxanthin improvement. Bioresource Technology 2022, 347, 126401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longworth, J.; Wu, D.; Huete-Ortega, M.; Wright, P.C.; Vaidyanathan, S. Proteome response of Phaeodactylum tricornutum, during lipid accumulation induced by nitrogen depletion. Algal research 2016, 18, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Cao, T.; Dautermann, O.; Buschbeck, P.; Cantrell, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Lein, C.D.; Shi, X.; Ware, M.A.; Yang, F.; et al. Green diatom mutants reveal an intricate biosynthetic pathway of fucoxanthin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2203708119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambek, M.; Eilers, U.; Breitenbach, J.; Steiger, S.; Büchel, C.; Sandmann, G. Biosynthesis of fucoxanthin and diadinoxanthin and function of initial pathway genes in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Journal of Experimental Botany 2012, 63, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Z.; Keereetaweep, J.; Liu, H.; Xu, C.; Shanklin, J. The role of sugar signaling in regulating plant fatty acid synthesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 643843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).