Submitted:

17 November 2023

Posted:

20 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

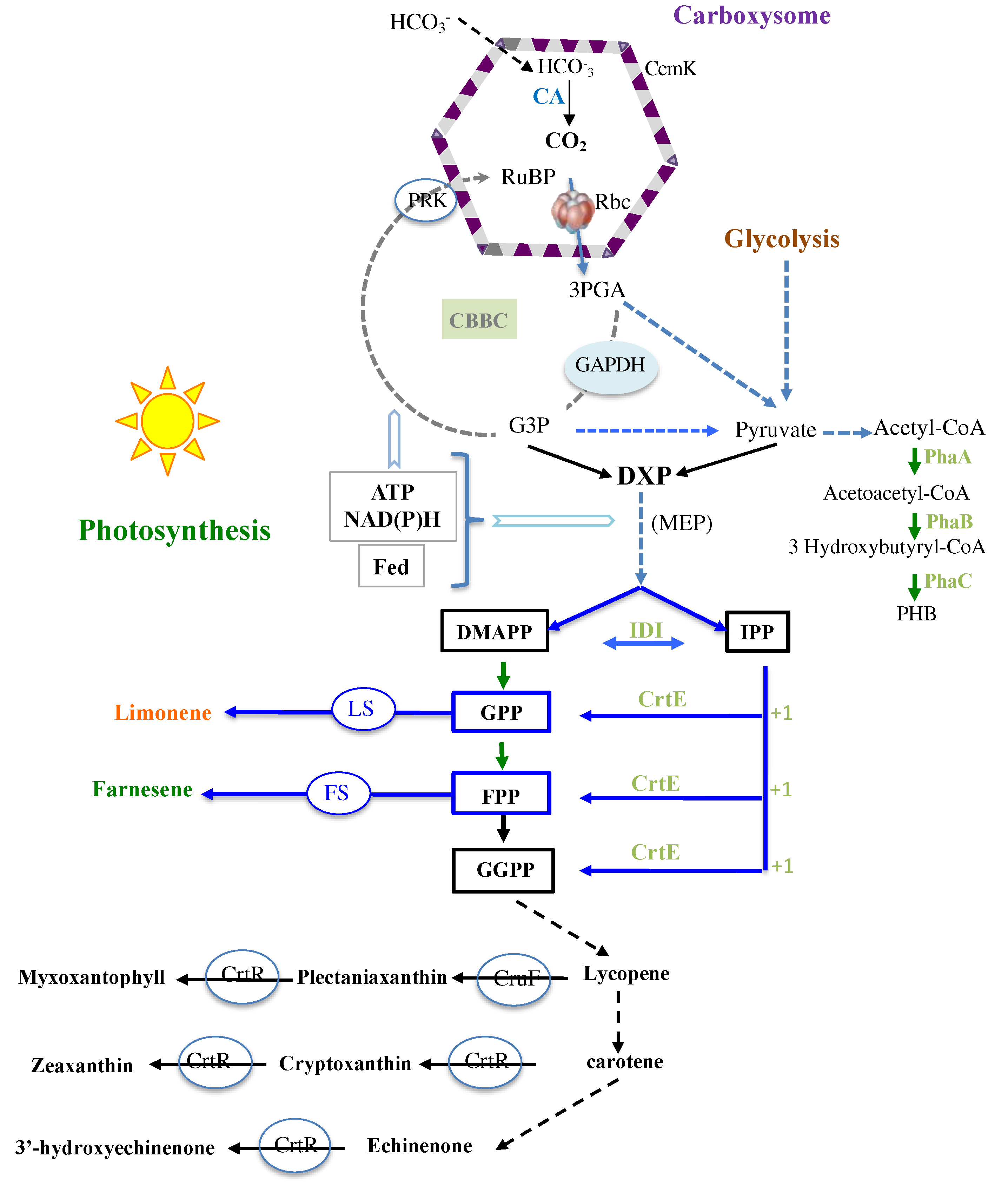

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

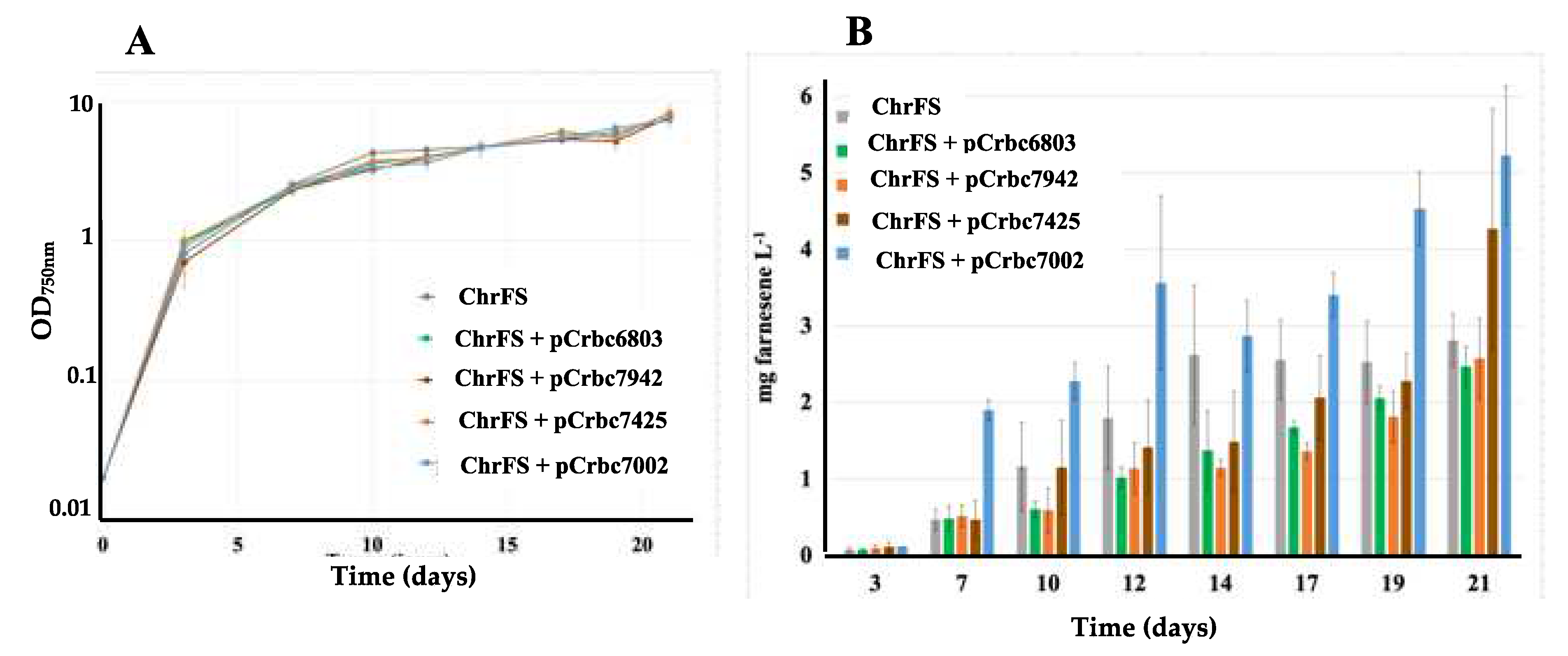

2.1. The Overexpression of the RubisCO genes from Synechococcus PCC 7002 Increases Farnesene Production in Synechocystis PCC 6803

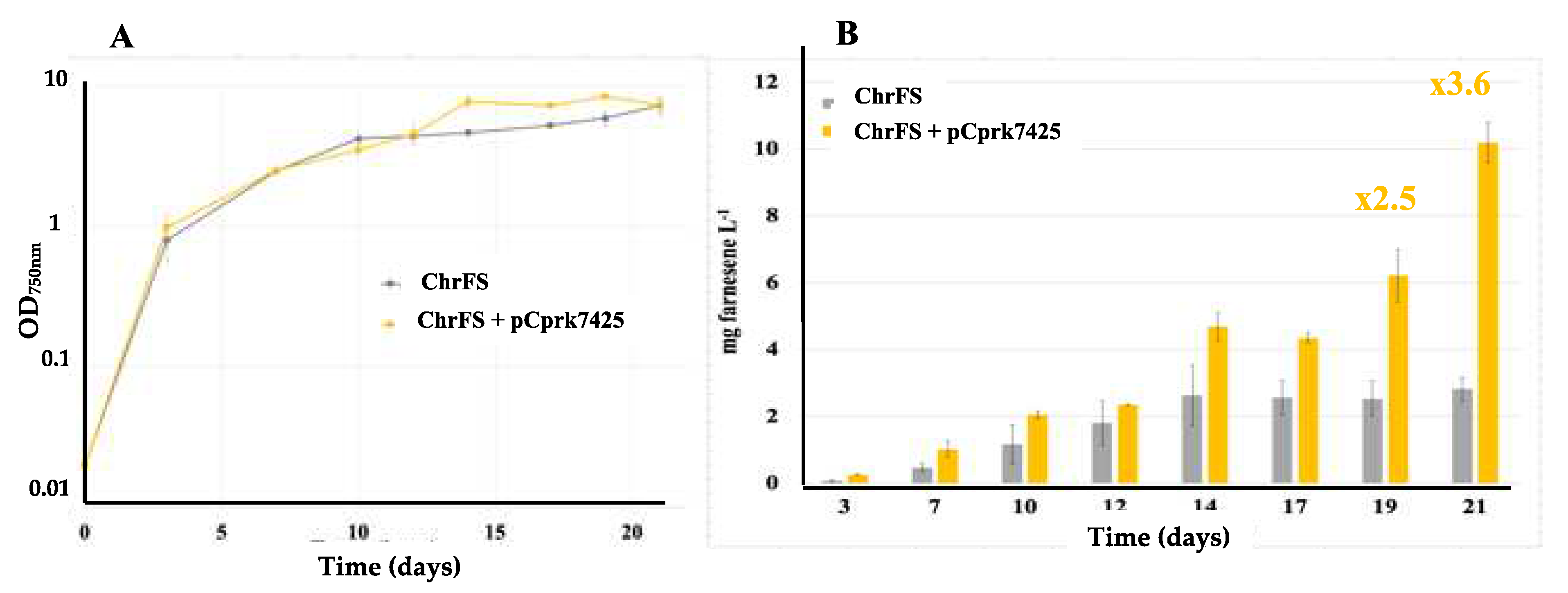

2.2. The Overexpression of the Phosphoribulokinase Gene from Cyanothece PCC 7425 Increases Farnesene Production in Synechocystis PCC 6803

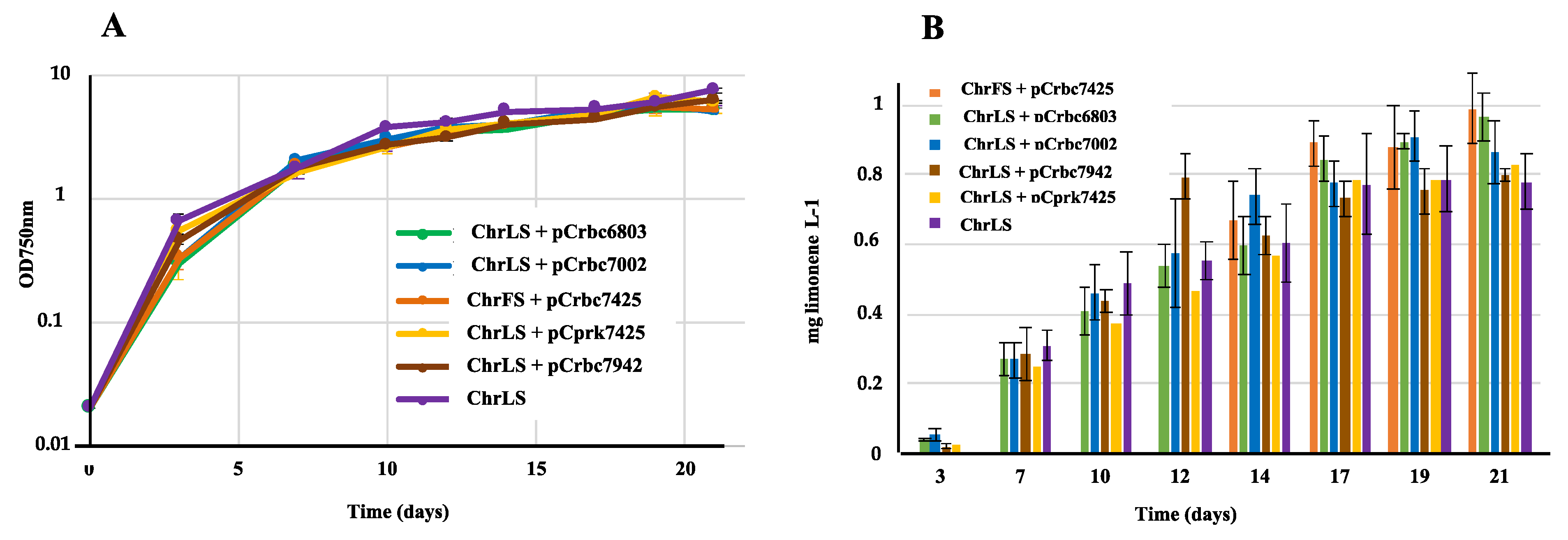

2.3. The Overexpression of the Genes Encoding Rubisco and PRK Enzymes does not Increase Limonene Production in Synechococcus PCC 7002

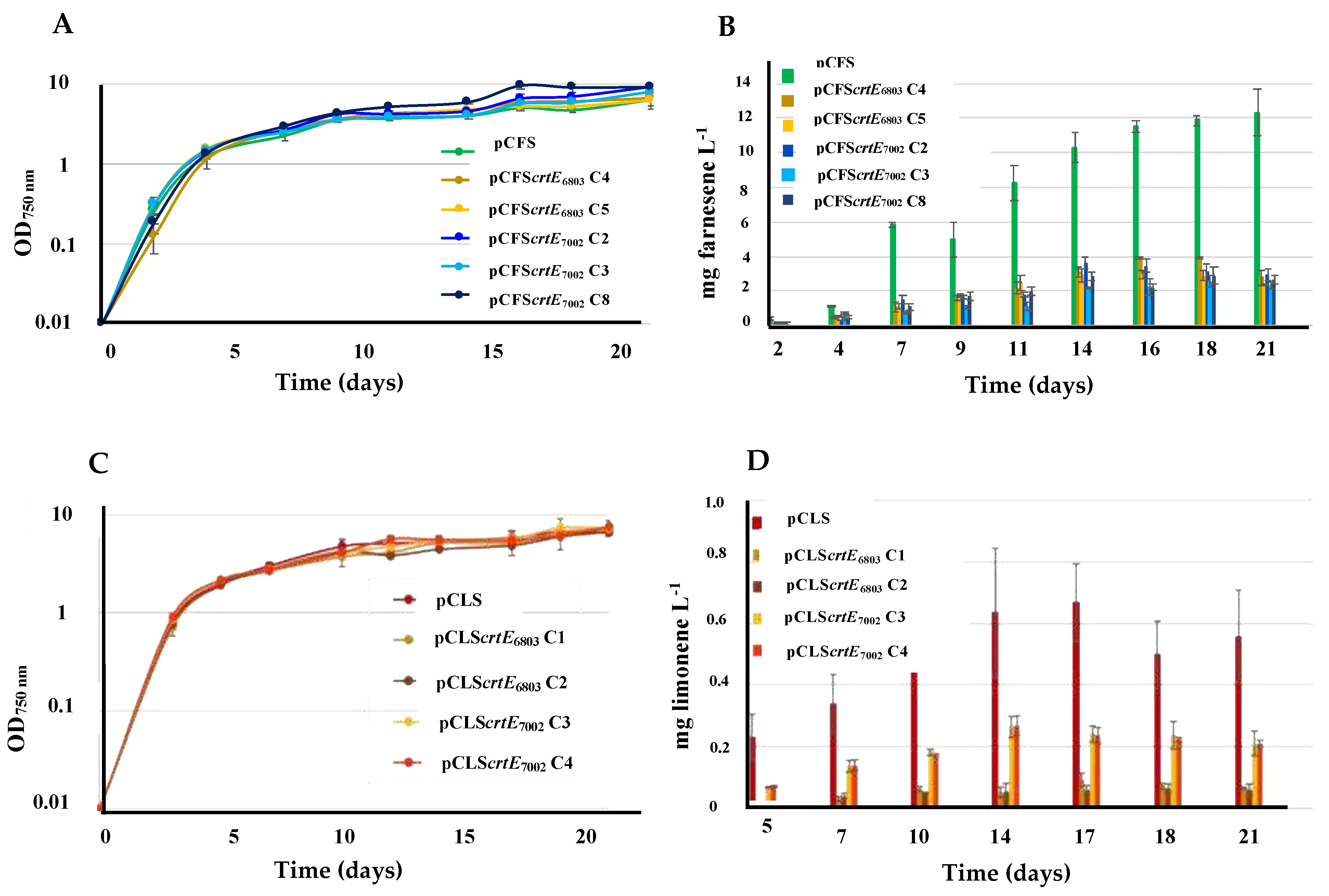

2.4. The Overexpression of the Crte Genes from Synechocystis PCC 6803 or Synechococcus PCC 7002 Decreases the Production of Both Farnesene and Limonene in Synechocystis PCC 6803

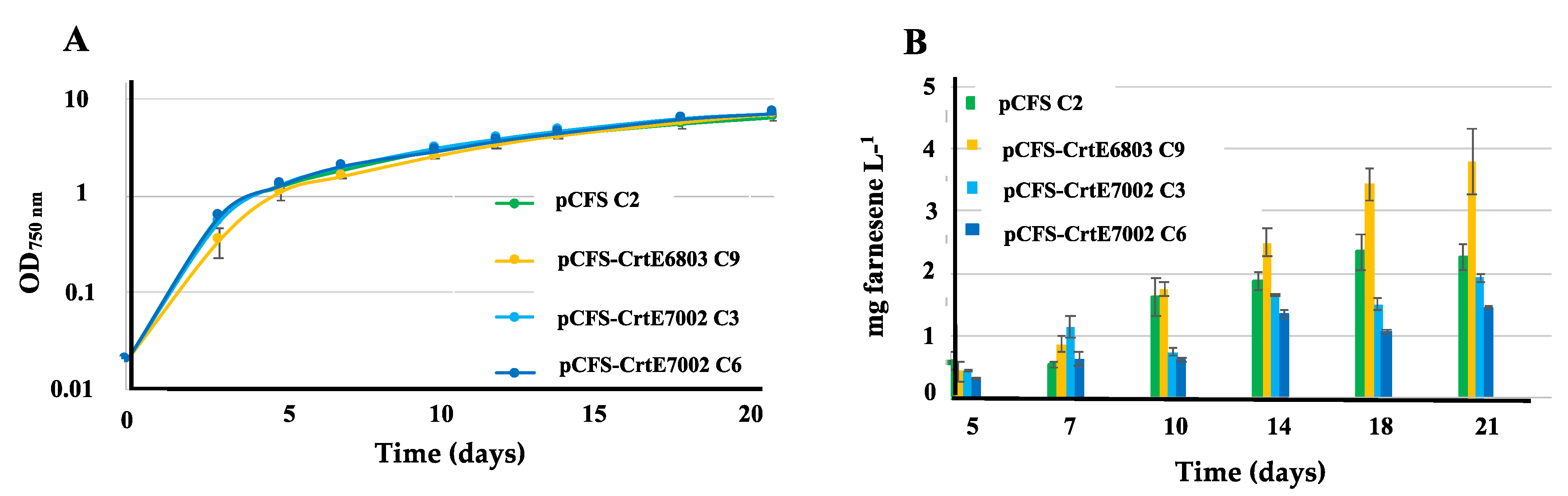

2.5. The Overexpression of the Crte Gene from Synechocystis PCC 6803, but not Synechococcus PCC 7002 Increases Farnesene Production in Synechococcus PCC 7002

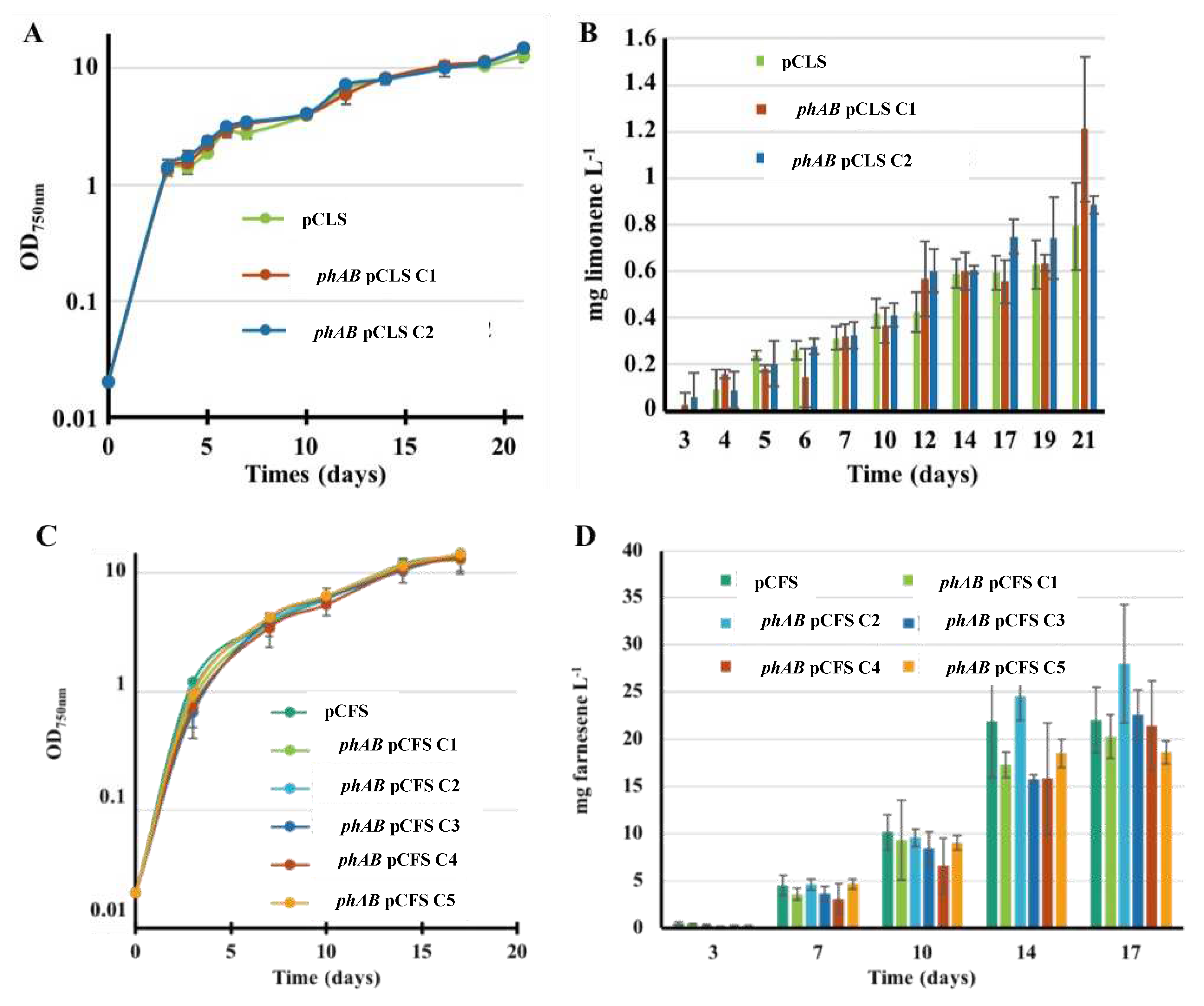

2.6. The Deletion of PHB Synthesis Genes does not Increase the Photoproduction of Terpenes in Synechocystis PCC 6803

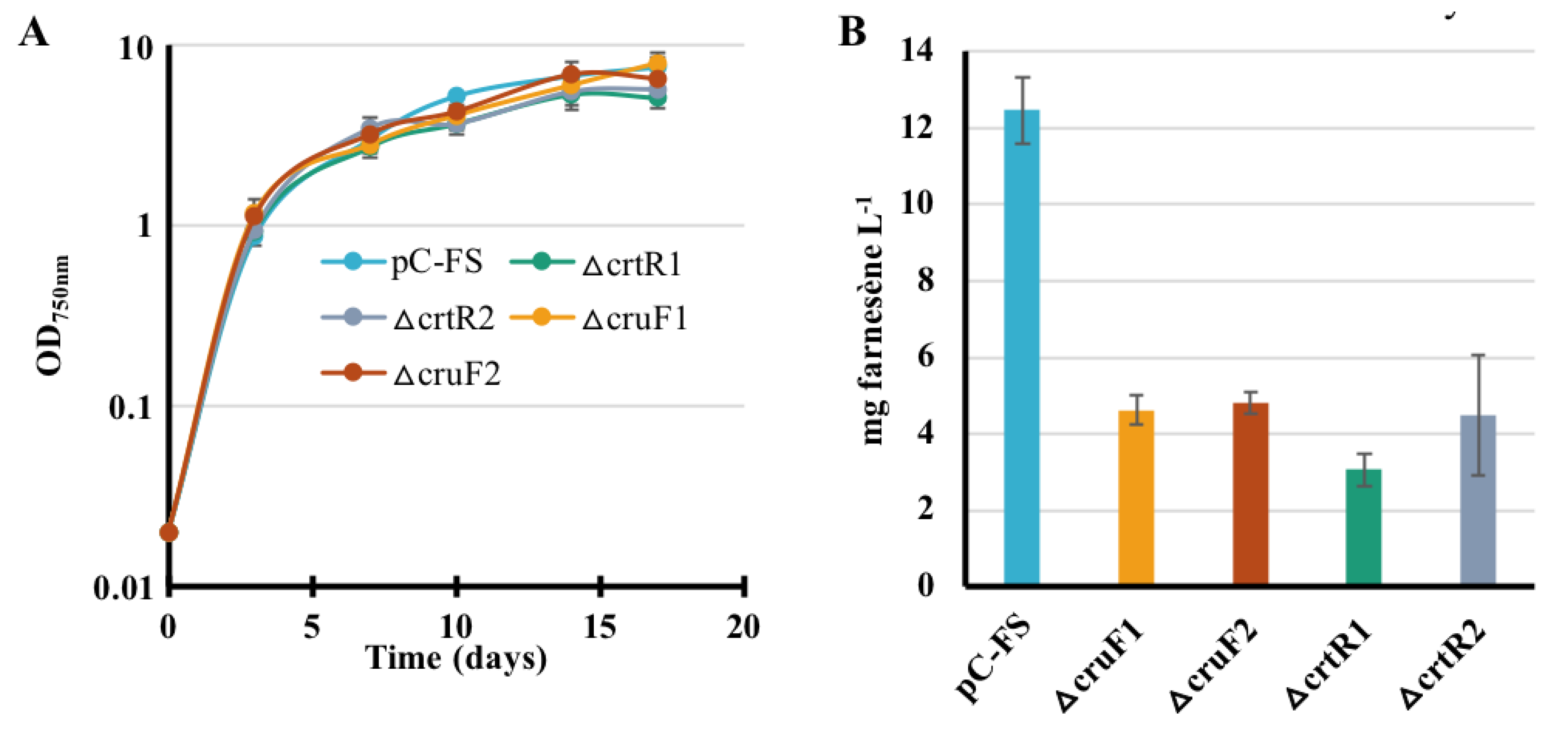

2.7. The Deletion of the Carotenoid Synthesis Genes crtR and cruF Decreases the Production of Farnesene in Synechocystis PCC6803

2.8. Deletion of Both the ccmK3 and ccmK4 Genes Encoding Carboxysome Shell Proteins does not Alter the Production of Limonene but Decreases the Production of Farnesene in Synechocystis PCC 6803

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

3.2. Genetic Manipulations and Gene Transfer Techniques

3.3. Terpenes Collection, and Quantification by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, P.C.; Pakrasi, H.B. Engineering cyanobacteria for production of terpenoids. Planta 2019, 249, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautela, A.; Kumar, S. Engineering plant family TPS into cyanobacterial host for terpenoids production. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1791–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veaudor, T.; Blanc-Garin, V.; Chenebault, C.; Diaz-Santos, E.; Sassi, J.F.; Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Chauvat, F. Recent advances in the photoautotrophic metabolism of cyanobacteria: Biotechnological implications. Life 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanova, E.; Pronina, N.A.; Los, D.L. Adapting from Low to High: An Update to CO2-Concentrating Mechanisms of Cyanobacteria and Microalgae. Plants 2023, 12, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Morgan, R.M.L.; Fraser, P.D.; Hellgardt, K.; Nixon, P.J. Crystal Structure of Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate Synthase (CrtE) Involved in Cyanobacterial Terpenoid Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Blanc-Garin, V.; Chauvat, F. Genetic, Genomics, and Responses to Stresses in Cyanobacteria: Biotechnological Implications. Genes 2021, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenebault, C.; Diaz-Santos, E.; Kammerscheit, X.; Görgen, S.; Ilioaia, C.; Streckaite, S.; Gall, A.; Robert, B.; Marcon, E.; Buisson, D.-A.; et al. A Genetic Toolbox for the New Model Cyanobacterium Cyanothece PCC 7425: A Case Study for the Photosynthetic Production of Limonene. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Garin, V.; Chenebault, C.; Diaz-Santos, E.; Vincent, M.; Sassi, J.F.; Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Chauvat, F. Exploring the potential of the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 for the photosynthetic production of various high-value terpenes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc-Garin, V.; Veaudor, T.; Sétif, P.; Gontero, B.; Lemaire, S.D.; Chauvat, F.; Cassier-Chauvat, C. First in vivo analysis of the regulatory protein CP12 of the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803: Biotechnological implications. Front. Plant Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenebault, C.; Blanc-Garin, V.; Vincent, M.; Diaz-Santos, E.; Goudet, A.; Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Chauvat, F. Exploring the Potential of the Model Cyanobacteria Synechococcus PCC 7002 and PCC 7942 for the Photoproduction of High-Value Terpenes. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsumi, S.; Higashide, W.; Liao, J.C. Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 1177–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffing, A.M. Improved free fatty acid production in cyanobacteria with Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 as host. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, F.; Englund, E.; Lindberg, P.; Lindblad, P. Engineered cyanobacteria with enhanced growth show increased ethanol production and higher biofuel to biomass ratio. Metab. Eng. 2018, 46, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharasirivat, V.; Jantaro, S. Increased Biomass and Polyhydroxybutyrate Production by Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Overexpressing RuBisCO Genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emlyn-Jones, D.; Woodger, F.J.; Price, G.D.; Whitney, S.M. RbcX can function as a Rubisco chaperonin, but is non-essential in Synechococcus PCC7942. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracher, A.; Whitney, S.M.; Hartl, F.U.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Biogenesis and Metabolic Maintenance of Rubisco. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017, 68, 29–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermet-Bouvier, P.; Chauvat, F. A conditional expression vector for the cyanobacteria Synechocystis sp. strains PCC6803 and PCC6714 or Synechococcus sp. strains PCC7942 and PCC6301. Curr. Microbiol. 1994, 28, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veaudor, T.; Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Chauvat, F. Overproduction of the cyanobacterial hydrogenase and selection of a mutant thriving on urea, as a possible step towards the future production of hydrogen coupled with water treatment. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, D.; Tamoi, M.; Iwaki, T.; Shigeoka, S.; Wanado, A. Molecular characterization and redox regulation of phosphoribulokinase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiguchi, H.; Liao, J.; Shimizu, H.; Matsuda, F. Novel allosteric inhibition of phosphoribulokinase identified by ensemble kinetic modeling of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 metabolism. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2020, 11, e00153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohto, C.; Ishida, C.; Nakane, H.; Nishiro, T.; Obata, S. A thermophilic cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus has three different Class I prenyltransferase genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 40, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.S.; Lindberg, P. Metabolic engineering of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 for improved bisabolene production. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2021, 12, e00159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satta, A.; Esquirol, L.; Ebert, B.E.; Newman, J.; Peat, T.S.; Plan, M.; Schenk, G.; Vickers, C.E. Molecular characterization of cyanobacterial short-chain prenyltransferases and discovery of a novel GGPP phosphatase. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 6672–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsami, E.A.; Psychogyiou, M.E.; Pateraki, A.; Chrysoulaki, E.; Melis, A.; Ghanotakis, D.F. Fusion constructs enhance heterologous β-phellandrene production in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.; Sim, S.J.; Um, Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, T.S.; Keasling, J.D.; Woo, H.M. Photosynthetic conversion of CO2 to farnesyl diphosphate-derived phytochemicals (amorpha-4,11-diene and squalene) by engineered cyanobacteria. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Saha, R.; Zhang, F.; Pakrasi, H.B. Metabolic engineering of the pentose phosphate pathway for enhanced limonene production in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betterle, N.; Melis, A. Photosynthetic generation of heterologous terpenoids in cyanobacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Long, B.; Dai, S.Y.; Golden, J.W.; Wang, X.; Yuan, J. Altered Carbon Partitioning Enhances CO2 to Terpene Conversion in Cyanobacteria. BioDesign Res. 2022, 9897425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, G.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Lu, X. Progress and perspective on cyanobacterial glycogen metabolism engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Forchhammer, K. Polyhydroxybutyrate: A Useful Product of Chlorotic Cyanobacteria. Microbiol Physiol. 2021, 31, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, A. Carbon partitioning in photosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taroncher-Oldenbourg, G.; Nishina, K.; Stephanopulos, G. Identification and Analysis of the Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Specific β-Ketothiolase and Acetoacetyl Coenzyme A Reductase Genes in the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC6803. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 4440–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetkorn, W.; Incharoensakdi, A.; Lindblad, P.; Jantaro, S. Enhancement of poly-3-hydroxybutyrate production in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 by overexpression of its native biosynthetic genes. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 214, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, R.; Incharroensakdi, A. Disruption of Polyhydroxybutyrate Synthesis Redirects Carbon Flow towards Glycogen Synthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 Overexpressing glgC/glgA. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Bryant, D.A. Metabolic engineering of Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 to produce poly-3-hydroxybutyrate and poly-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate. Metab. Eng. 2015, 32, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagels, F.; Vasconcelos, V.; Guedes, A.C. Carotenoids from Cyanobacteria: Biotechnological Potential and Optimization Strategies. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, D.; Vermaas, W. The zeaxanthin biosynthesis enzyme beta-carotene hydroxylase is involved in myxoxanthophyll synthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett. 1999, 454, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, L.; Vioque, A.; Sandmann, G. Functional in situ evaluation of photosynthesis-protecting carotenoids in mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2005, 78, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.L.; Gordon, G.C.; Bennett, N.R.; Lyu, H.; Root, T.W.; Pfleger, B.F. High-CO2 Requirement as a Mechanism for the Containment of Genetically Modified Cyanobacteria. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, J., II; Woo, H.M. Biocontainment of Engineered Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 for Photosynthetic Production of α-Farnesene from CO2. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Alles, L.; Root, K.; Maveyraud, L.; Aubry, N.; Lesniewska, E.; Mourey, L.; Zenobi, R.; Truan, G. Occurrence and stability of hetero-hexamer associations formed by β-carboxysome CcmK shell components. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Sutter, M.; Gupta, S.; Kirst, H.; Turmo, A.; Lechno-Yossef, S.; Burton, R.L.; Saechao, C.; Sloan, N.B.; Cheng, X.; et al. Heterohexamers formed by CcmK3 and CcmK4 increase the complexity of beta carboxysome shells. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, B.D.; Long, B.M.; Badger, M.R.; Price, G.D. Structural determinants of the outer shell of β-carboxysomes in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942: Roles for CcmK2, K3-K4, CcmO, and CcmL. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Laborde, S.M.; Frankel, L.K.; Bricker, T.M. Four Novel Genes Required for Optimal Photoautotrophic Growth of the Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803 Identified by In Vitro Transposon Mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanier, R.Y.; Kunisawa, R.; Mandel, M.; Cohen-Bazire, G. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales). Bacteriol. Rev. 1971, 35, 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domain, F.; Houot, L.; Chauvat, F.; Cassier-Chauvat, C. Function and regulation of the cyanobacterial genes lexA, recA and ruvB: LexA is critical to the survival of cells facing inorganic carbon starvation. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, S.E.; Pat Paterson, C.O.; Myers, J. The production of hydrogen peroxide by blue-green algae: A survey. J. Phycol. 1973, 9, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mermet-Bouvier, P.; Cassier-Chauvat, C.; Marraccini, P.; Chauvat, F. Transfer and replication of RSF1010-derived plasmids in several cyanobacteria of the genera Synechocystis and Synechococcus. Curr. Microbiol. 1993, 27, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarre, J.; Chauvat, F.; Thuriaux, P. Insertional mutagenesis by random cloning of antibiotic resistance genes into the genome of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 3449–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).