Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials, Design, and Processing Methods

2.2. Screening and Physicochemical Properties Analysis of the GATA Gene Family

2.3. Analysis of GATA Gene Structure, Conserved Domain, and Motif

2.4. GATA Phylogeny and Amino Acid Homology Alignment

2.5. Prediction and Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in GATA Promoter

2.6. Heat Map Analysis of GATA Gene Expression

2.7. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.8. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.9. Interaction Network of GATA Transcription Factors

2.10. Data Statistics and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physical and Chemical Properties Analysis of GATA Transcription Factors

3.2. Prediction and Analysis of GATA Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs, and Conserved Domains

3.3. Phylogenetic Evolution and Conservative Structural Domain Analysis of GATA

3.4. GATA Chromosome Location Analysis

3.5. Analysis of Homeopathic Regulatory Elements in the GATA Promoter

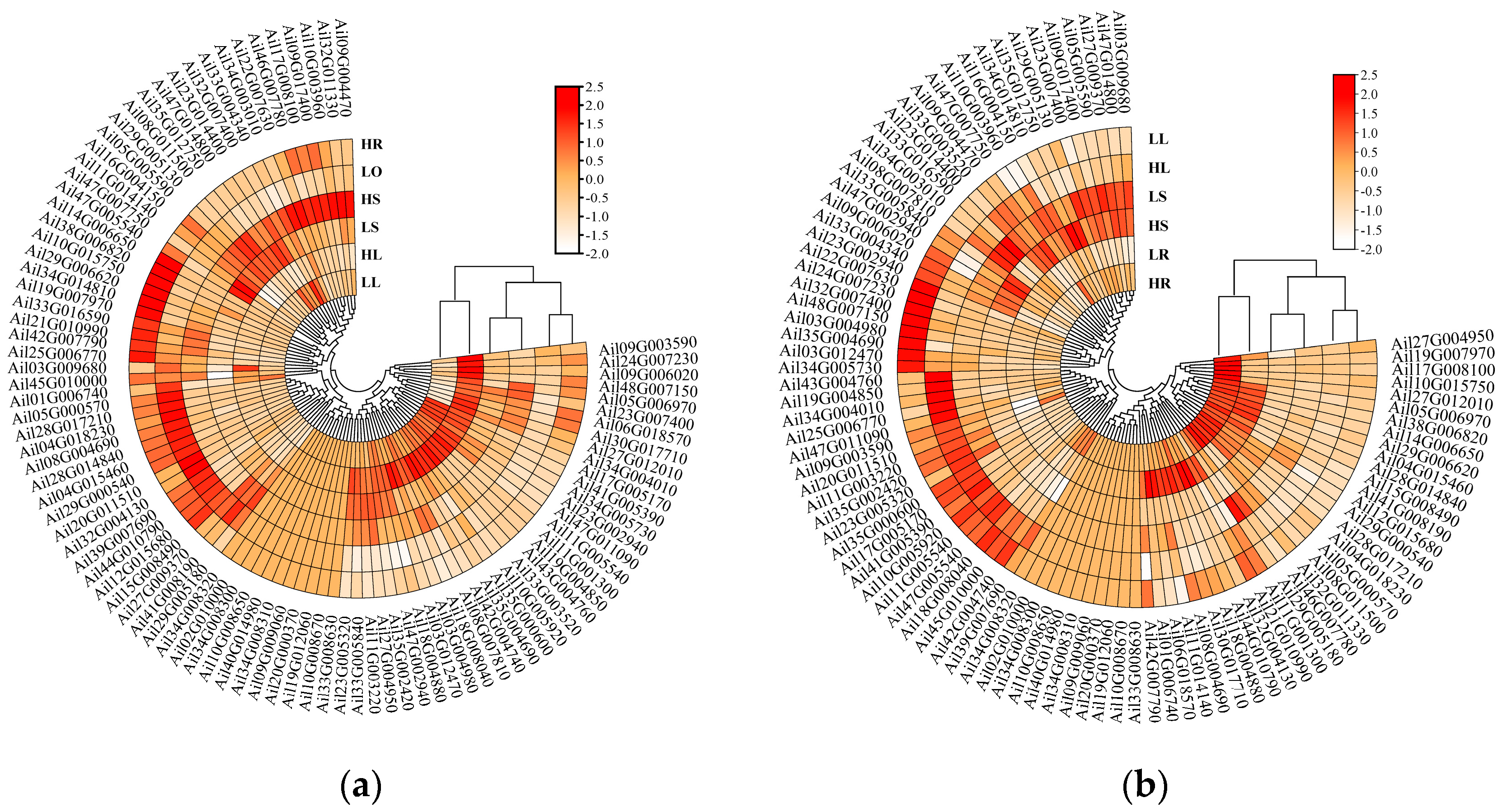

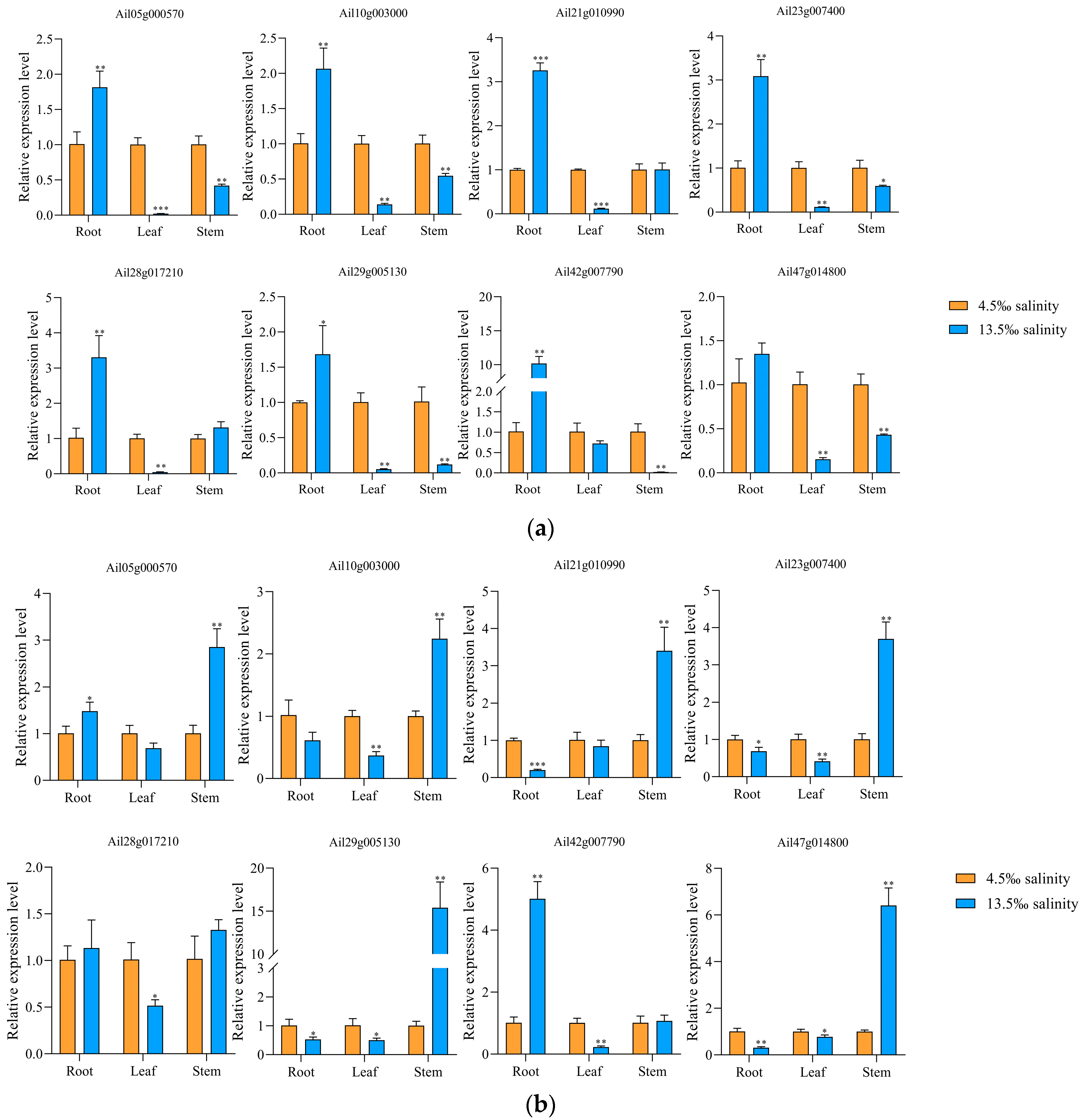

3.6. GATA Expression Heatmap Analysis

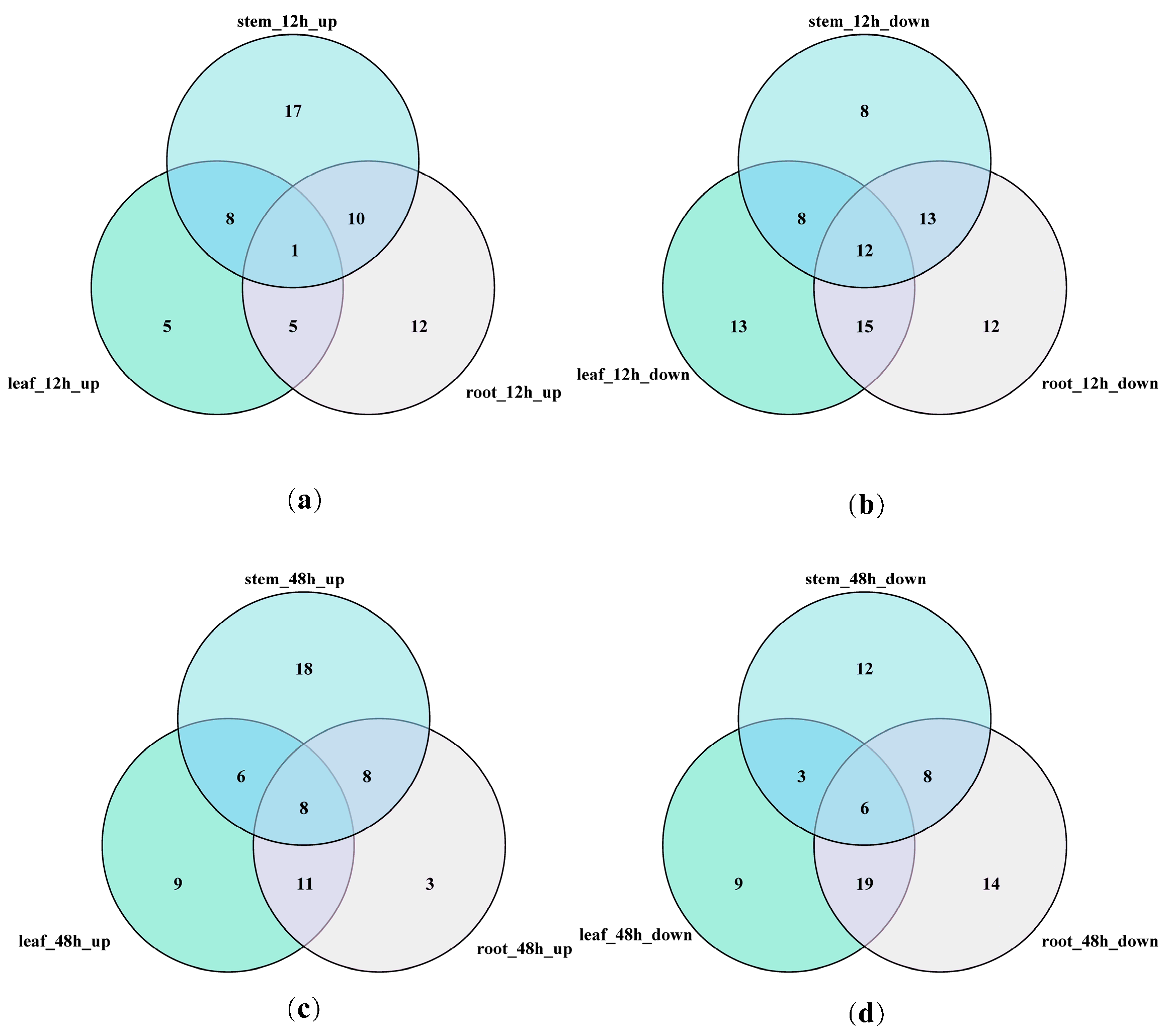

3.7. Venn Diagram of GATA Differentially Expressed Genes

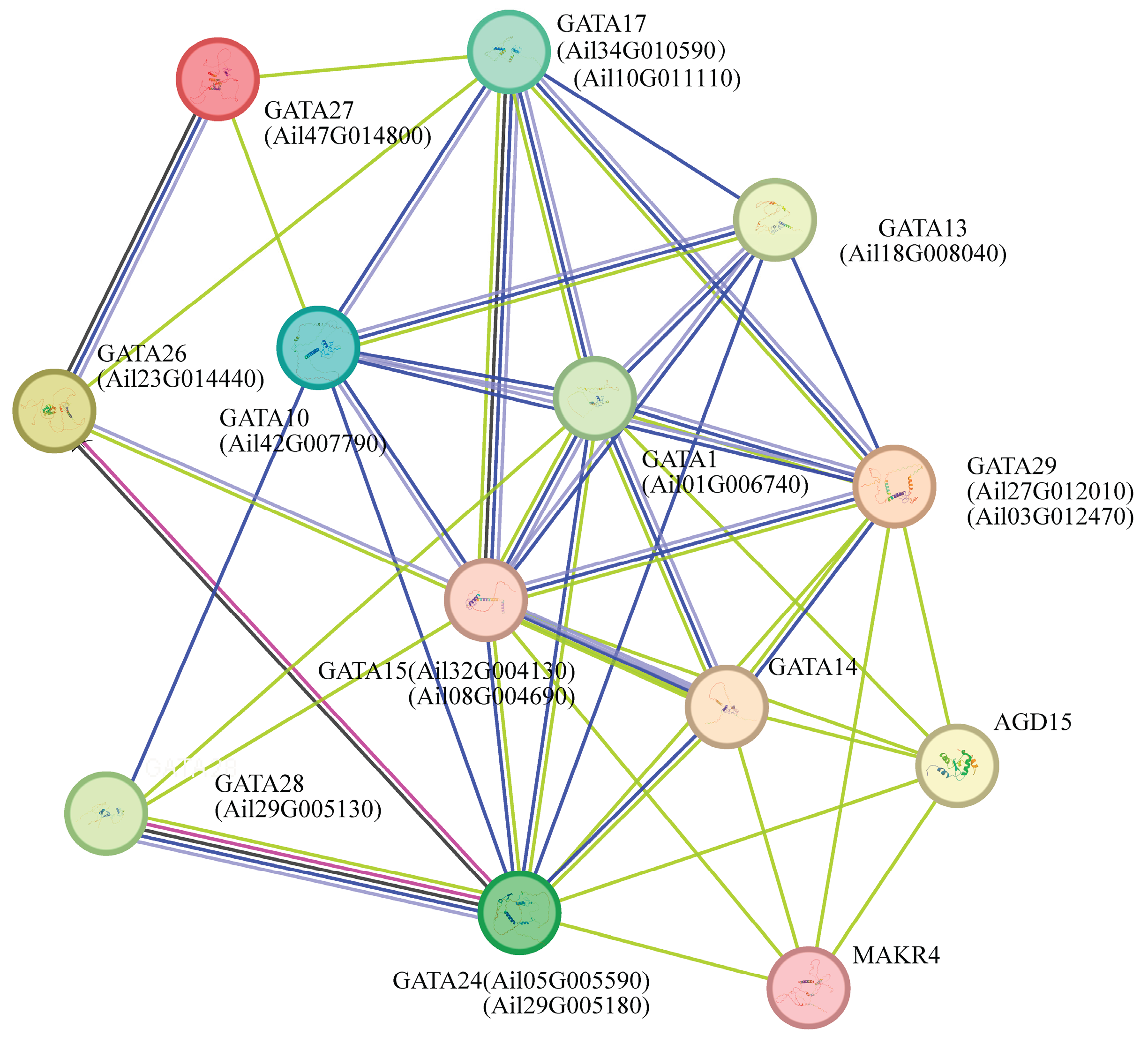

3.9. Interaction Network of GATA Transcription Factors in Arabidopsis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R.; et al. Arabidopsis Transcription Factors: Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis among Eukaryotes. Science 2000, 290, 2105–2110. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yan, J.; Lai, D.; Yang, H.; Xue, G.; He, A.; Guo, T.; Chen, L.; Cheng, X.; Xiang, D.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Expression Analysis, and Functional Study of the GRAS Transcription Factor Family and Its Response to Abiotic Stress in Sorghum [Sorghum Bicolor (L.) Moench]. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 509. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhou, M.; Ruan, J.; He, A.; Ma, C.; Wu, W.; Lai, D.; Fan, Y.; Gao, A.; Weng, W.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Evolution, and Expression Pattern Analysis of the GATA Gene Family in Tartary Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Tataricum). IJMS 2022, 23, 12434. [CrossRef]

- Rueda-López, M.; Cañas, R.A.; Canales, J.; Cánovas, F.M.; Ávila, C. The Overexpression of the Pine Transcription Factor PpDof 5 in Arabidopsis Leads to Increased Lignin Content and Affects Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism. Physiol. Plant. 2015, 155, 369–383. [CrossRef]

- Darigh, F.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Oraghi Ardebili, Z.; Ebadi, M.; Hassanpour, H. Simulated Microgravity Contributed to Modification of Callogenesis Performance and Secondary Metabolite Production in Cannabis Indica. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 186, 157–168. [CrossRef]

- Bose, C.; Das, P.K.; Roylawar, P.; Rupawate, P.; Khandagale, K.; Nanda, S.; Gawande, S. Identification and Analysis of the GATA Gene Family in Onion (Allium Cepa L.) in Response to Chromium and Salt Stress. BMC Genomics 2025, 26, 201. [CrossRef]

- Strader, L.; Weijers, D.; Wagner, D. Plant Transcription Factors — Being in the Right Place with the Right Company. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2022, 65, 102136. [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C.; Schroder, P.M.; Blaby-Haas, C.E. Plant GATA Factors: Their Biology, Phylogeny, and Phylogenomics. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2022, 73, 123–148. [CrossRef]

- Virolainen, P.A.; Chekunova, E.M. GATA Family Transcription Factors in Alga Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Curr Genet 2024, 70, 1. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Xi, H.; Park, S.; Yun, Y.; Park, J. Genome-Wide Comparative Analyses of GATA Transcription Factors among Seven Populus Genomes. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 16578. [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C.; Schröder, P.M.; Blaby-Haas, C.E. Plant GATA Factors: Their Biology, Phylogeny, and Phylogenomics. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 123–148. [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, S.; Kai, G. Genome-Wide Survey of the GATA Gene Family in Camptothecin-Producing Plant Ophiorrhiza Pumila. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 256. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Comparative Analysis of Amino Acid Sequence Level in Plant GATA Transcription Factors. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 29786. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hou, Y.; Hao, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; Yuan, S.; Shan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, D.; et al. Genome-Wide Survey of the Soybean GATA Transcription Factor Gene Family and Expression Analysis under Low Nitrogen Stress. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125174. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhong, W.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, P.; Wan, Y.; Shi, S.; Yang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Mu, F.; Chen, S. Integrative Analysis of Metabolome and Transcriptome Reveals the Improvements of Seed Quality in Vegetable Soybean (Glycine Max (L.) Merr.). Phytochemistry 2022, 200. [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Lai, D.; Zhou, M.; Ruan, J.; Ma, C.; Wu, W.; Weng, W.; Fan, Y.; Cheng, J. Genome-Wide Identification, Evolution and Expression Pattern Analysis of the GATA Gene Family in Sorghum Bicolor. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1163357. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Li, N.; Yin, Y.; Wang, F.; Gao, S.; Jiao, C.; Yao, M. Genome-Wide Identification and Function Characterization of GATA Transcription Factors during Development and in Response to Abiotic Stresses and Hormone Treatments in Pepper. J Appl Genetics 2021, 62, 265–280. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lai, X.; Luo, K.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, K.; Wan, X. Integrated Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses of Two Peanut (Arachis Hypogaea L.) Cultivars Differing in Amino Acid Metabolism of the Seeds. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 185, 132–143. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y. Comparative Analysis of the GATA Transcription Factors in Five Solanaceae Species and Their Responses to Salt Stress in Wolfberry (Lycium Barbarum L.). Genes 2023, 14, 1943. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yu, Q.; Zeng, J.; He, X.; Liu, W. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of GATA Family Genes in Wheat. BMC Plant Biol 2022, 22, 372. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jia, L.; Yang, D.; Hu, Y.; Njogu, M.K.; Wang, P.; Lu, X.; Yan, C. Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic and Expression Pattern Analysis of GATA Family Genes in Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.). Plants 2021, 10, 1626. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; Huang, Z.; Fan, S.; Qun, G.; Liu, A.; Gong, J.; Li, J.; Gong, W.; Shi, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of the Evolution and Expression Patterns of the GATA Transcription Factors in Three Species of Gossypium Genus. Gene 2019, 680, 72–83. [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Han, X.; Shen, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Yin, W.; Xia, X. The GATA Transcription Factor GNC Plays an Important Role in Photosynthesis and Growth in Poplar. Journal of Experimental Botany 2020, 71, 1969–1984. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, W.; Song, N.; Tang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Pan, S.; Dai, L.; Wang, B. Genome-Wide Characterization, Evolution, and Expression Profile Analysis of GATA Transcription Factors in Brachypodium Distachyon. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Nan, S.; Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, J.; Jin, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, S. Comprehensive Analysis and Characterization of the GATA Gene Family, with Emphasis on the GATA6 Transcription Factor in Poplar. IJMS 2023, 24, 14118. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-H.; Zubo, Y.O.; Tapken, W.; Kim, H.J.; Lavanway, A.M.; Howard, L.; Pilon, M.; Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Functional Characterization of the GATA Transcription Factors GNC and CGA1 Reveals Their Key Role in Chloroplast Development, Growth, and Division in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2012, 160, 332–348. [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Behringer, C.; Zourelidou, M.; Schwechheimer, C. Convergence of Auxin and Gibberellin Signaling on the Regulation of the GATA Transcription Factors GNC and GNL in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 13192–13197. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.-M.; Lin, W.-H.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Sun, Y.; Fan, X.-Y.; Cheng, M.; Hao, Y.; Oh, E.; Tian, M.; et al. Integration of Light- and Brassinosteroid-Signaling Pathways by a GATA Transcription Factor in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 2010, 19, 872–883. [CrossRef]

- Zubo, Y.O.; Blakley, I.C.; Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; Yamburenko, M.V.; Solano, R.; Kieber, J.J.; Loraine, A.E.; Schaller, G.E. Coordination of Chloroplast Development through the Action of the GNC and GLK Transcription Factor Families. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 130–147. [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xie, J.; Ni, J.; et al. Short and Narrow Flag Leaf1, a GATA Zinc Finger Domain-Containing Protein, Regulates Flag Leaf Size in Rice (Oryza Sativa). BMC Plant Biol 2018, 18, 273. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Nutan, K.K.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A. Abiotic Stresses Cause Differential Regulation of Alternative Splice Forms of GATA Transcription Factor in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1944. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Casaretto, J.A.; Ying, S.; Mahmood, K.; Liu, F.; Bi, Y.-M.; Rothstein, S.J. Overexpression of OsGATA12 Regulates Chlorophyll Content, Delays Plant Senescence and Improves Rice Yield under High Density Planting. Plant Mol Biol 2017, 94, 215–227. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, T.; Li, Z.; Huang, K.; Kim, N.-E.; Ma, Z.; Kwon, S.-W.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. OsGATA16, a GATA Transcription Factor, Confers Cold Tolerance by Repressing OsWRKY45–1 at the Seedling Stage in Rice. Rice 2021, 14, 42. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, E.; Yavuz, C.; Yagiz, A.K.; Unel, N.M.; Baloglu, M.C. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of GATA Transcription Factors under Combination of Light Wavelengths and Drought Stress in Potato. Plant Direct 2024, 8, e569. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Duan, H.; Zhang, N.; Majeed, Y.; Jin, H.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification of GATA Family Genes in Potato and Characterization of StGATA12 in Response to Salinity and Osmotic Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.A.; Sabir, I.A.; Shah, I.H.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Rasool, F.; Mazhar, M.Z.; Younas, S.; Abdullah, M.; Cai, Y. Comprehensive Comparative Analysis of the GATA Transcription Factors in Four Rosaceae Species and Phytohormonal Response in Chinese Pear (Pyrus Bretschneideri) Fruit. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Donato, D.C.; Kauffman, J.B.; Murdiyarso, D.; Kurnianto, S.; Stidham, M.; Kanninen, M. Mangroves among the Most Carbon-Rich Forests in the Tropics. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 293–297. [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.K.; Jha, B. Salt Tolerance Mechanisms in Mangroves: A Review. Trees 2010, 24, 199–217. [CrossRef]

- Friess, D.A.; Rogers, K.; Lovelock, C.E.; Krauss, K.W.; Hamilton, S.E.; Lee, S.Y.; Lucas, R.; Primavera, J.; Rajkaran, A.; Shi, S. The State of the World’s Mangrove Forests: Past, Present, and Future. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 89–115. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.K.; Singh, R.; Kathiresan, K. Multi-Gene Phylogenetic Analysis Reveals the Multiple Origin and Evolution of Mangrove Physiological Traits through Exaptation. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 2016, 183, 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xie, Y.; Liu, G.; Shang, X.; Zhan, N. Transcriptome and Metabolome Profiling Provide Insights into Flavonoid Synthesis in Acanthus Ilicifolius Linn. Genes 2023, 14, 752. [CrossRef]

- Lowry, J.A.; Atchley, W.R. Molecular Evolution of the GATA Family of Transcription Factors: Conservation Within the DNA-Binding Domain. J Mol Evol 2000, 50, 103–115. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zong, X.; Ren, P.; Qian, Y.; Fu, A. Basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) Transcription Factors Regulate a Wide Range of Functions in Arabidopsis. IJMS 2021, 22, 7152. [CrossRef]

- Atchley, W.; Fitch, W. A Natural Classification of the Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Class of Transcription Factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997, 94 10, 5172–5176. [CrossRef]

- Behringer, C.; Schwechheimer, C. B-GATA Transcription Factors – Insights into Their Structure, Regulation, and Role in Plant Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 90. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X.; Fu, M.; Yang, Q.; Liu, L.; Wan, X.; Chen, Q. Identification of the GATA Transcription Factor Family in Tea Plant (Camellia Sinensis) and the Characterizations in Nitrogen Metabolism. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2025, 221, 109661. [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Xia, Y.; Zhan, D.; Xu, T.; Lu, T.; Yang, J.; Kang, X. Genome-Wide Identification of the Eucalyptus Urophylla GATA Gene Family and Its Diverse Roles in Chlorophyll Biosynthesis. IJMS 2022, 23, 5251. [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Liao, W.; Li, J.; Pan, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, S. Genome-Wide Identification of GATA Family Genes in Phoebe Bournei and Their Transcriptional Analysis under Abiotic Stresses. IJMS 2023, 24, 10342. [CrossRef]

- Hwarari, D.; Radani, Y.; Guan, Y.; Chen, J.; Liming, Y. Systematic Characterization of GATA Transcription Factors in Liriodendron Chinense and Functional Validation in Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 2349. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Mu, D.; Wilson, I.W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, X.; Luo, L.; He, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification of GATA Transcription Factor Family and the Effect of Different Light Quality on the Accumulation of Terpenoid Indole Alkaloids in Uncaria Rhynchophylla. Plant Mol Biol 2024, 114, 15. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.-K.; Rao, G.-Y. Insights into the Diversification and Evolution of R2R3-MYB Transcription Factors in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 637–655. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Wang, H.-W.; Cao, Y.-N.; Kan, S.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y. Comprehensive Evolutionary Analysis of the TCP Gene Family: Further Insights for Its Origin, Expansion, and Diversification. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 994567. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, R.; Yu, T.; Shen, S.; Cao, R.; Ma, X.; Song, X. Large-scale Analysis of Trihelix Transcription Factors Reveals Their Expansion and Evolutionary Footprint in Plants. Physiologia Plantarum 2023, 175, e14039. [CrossRef]

- Mengarelli, D.A.; Zanor, M.I. Genome-Wide Characterization and Analysis of the CCT Motif Family Genes in Soybean (Glycine Max). Planta 2021, 253, 15. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Tai, Z.; Hu, K.; Luo, L.; Yang, S.; Liu, M.; Xie, X. Comprehensive Review on Plant Cytochrome P450 Evolution: Copy Number, Diversity, and Motif Analysis From Chlorophyta to Dicotyledoneae. Genome Biol. Evol. 2024, 16, evae240. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Gu, X.; Peterson, T. Identification of Conserved Gene Structures and Carboxy-Terminal Motifs in the Myb Gene Family of Arabidopsis and Oryza Sativa L. Ssp. Indica. Genome Biol 2004, 5, R46. [CrossRef]

- Gushchina, L.V.; Kwiatkowski, T.A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Weisleder, N.L. Conserved Structural and Functional Aspects of the Tripartite Motif Gene Family Point towards Therapeutic Applications in Multiple Diseases. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2018, 185, 12–25. [CrossRef]

- Corbin, C.; Drouet, S.; Markulin, L.; Auguin, D.; Lainé, É.; Davin, L.B.; Cort, J.R.; Lewis, N.G.; Hano, C. A Genome-Wide Analysis of the Flax (Linum Usitatissimum L.) Dirigent Protein Family: From Gene Identification and Evolution to Differential Regulation. Plant Mol Biol 2018, 97, 73–101. [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Lu, Y.; Sun, H.; Duan, W.; Hu, Y.; Yan, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis of Wheat GATA Transcription Factor Genes Reveals Their Molecular Evolutionary Characteristics and Involvement in Salt and Drought Tolerance. IJMS 2022, 24, 27. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Bai, X.; Dai, K.; Yuan, X.; Guo, P.; Zhou, M.; Shi, W.; Hao, C. Identification of GATA Transcription Factors in Brachypodium Distachyon and Functional Characterization of BdGATA13 in Drought Tolerance and Response to Gibberellins. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 763665. [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, M.F.; Mostafa, K.; Aydin, A.; Kavas, M.; Aksoy, E. GATA Transcription Factor in Common Bean: A Comprehensive Genome-Wide Functional Characterization, Identification, and Abiotic Stress Response Evaluation. Plant Mol Biol 2024, 114, 43. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, H.; Bi, Y. cGMP Regulates Hydrogen Peroxide Accumulation in Calcium-Dependent Salt Resistance Pathway in Arabidopsis Thaliana Roots. Planta 2011, 234, 709–722. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhai, H.; He, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Liu, Q. A Novel Sweetpotato GATA Transcription Factor, IbGATA24, Interacting with IbCOP9-5a Positively Regulates Drought and Salt Tolerance. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2022, 194, 104735. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jia, K.; Tian, Y.; Han, K.; El-Kassaby, Y.A.; Yang, H.; Si, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y. Time-Course Transcriptomics Analysis Reveals Key Responses of Populus to Salt Stress. Industrial Crops and Products 2023, 194, 116278. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y. Comparative Analysis of the GATA Transcription Factors in Five Solanaceae Species and Their Responses to Salt Stress in Wolfberry (Lycium Barbarum L.). Genes 2023, 14, 1943. [CrossRef]

- Gémes, K.; Poór, P.; Horváth, E.; Kolbert, Z.; Szopkó, D.; Szepesi, Á.; Tari, I. Cross-talk between Salicylic Acid and NaCl-generated Reactive Oxygen Species and Nitric Oxide in Tomato during Acclimation to High Salinity. Physiologia Plantarum 2011, 142, 179–192. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Cai, J.; Deng, L.; Li, G.; Sun, J.; Han, Y.; Dong, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, T.; Liu, S.; et al. SlSTE1 Promotes Abscisic Acid-dependent Salt Stress-responsive Pathways via Improving Ion Homeostasis and Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging in Tomato. JIPB 2020, 62, 1942–1966.

- Julkowska, M.M.; Testerink, C. Tuning Plant Signaling and Growth to Survive Salt. Trends in Plant Science 2015, 20, 586–594. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.Y.; Jin, J.F.; Lou, H.Q.; Dang, F.F.; Xu, J.M.; Zheng, S.J.; Yang, J.L. Abscisic Acid-dependent PMT1 Expression Regulates Salt Tolerance by Alleviating Abscisic Acid-mediated Reactive Oxygen Species Production in Arabidopsis. JIPB 2022, 64, 1803–1820. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, N.; Ji, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Lyu, M.; You, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A GmSIN1/GmNCED3s/GmRbohBs Feed-Forward Loop Acts as a Signal Amplifier That Regulates Root Growth in Soybean Exposed to Salt Stress. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2107–2130. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Tian, Y.; Hou, X.; Hou, X.; Jia, Z.; Li, M.; Hao, M.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Pu, Q.; et al. Multiple Forms of Vitamin B6 Regulate Salt Tolerance by Balancing ROS and Abscisic Acid Levels in Maize Root. Stress Biology 2022, 2, 39. [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Zhang, B.-L.; Li, F.; Li, Y.-R.; Li, J.-H.; Lu, Y.-T. General Control Non-Repressible 20 Functions in the Salt Stress Response of Arabidopsis Seedling by Modulating ABA Accumulation. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2022, 198, 104856. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, C.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Deng, S.; Zhao, N.; Sa, G.; Zhou, X.; Lu, C.; et al. Populus Euphratica JRL Mediates ABA Response, Ionic and ROS Homeostasis in Arabidopsis under Salt Stress. IJMS 2019, 20, 815. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Matsuda, O.; Iba, K. ITN1 , a Novel Gene Encoding an Ankyrin-repeat Protein That Affects the ABA-mediated Production of Reactive Oxygen Species and Is Involved in Salt-stress Tolerance in Arabidopsis Thaliana. The Plant Journal 2008, 56, 411–422. [CrossRef]

- Rachowka, J.; Anielska-Mazur, A.; Bucholc, M.; Stephenson, K.; Kulik, A. SnRK2.10 Kinase Differentially Modulates Expression of Hub WRKY Transcription Factors Genes under Salinity and Oxidative Stress in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1135240. [CrossRef]

- Laohavisit, A.; Shang, Z.; Rubio, L.; Cuin, T.A.; Véry, A.-A.; Wang, A.; Mortimer, J.C.; Macpherson, N.; Coxon, K.M.; Battey, N.H.; et al. Arabidopsis Annexin1 Mediates the Radical-Activated Plasma Membrane Ca2+ - and K+ -Permeable Conductance in Root Cells. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 1522–1533. [CrossRef]

- Price, A.H.; Taylor, A.; Ripley, S.J.; Griffiths, A.; Trewavas, A.J.; Knight, M.R. Oxidative Signals in Tobacco Increase Cytosolic Calcium. Plant Cell 1994, 1301–1310. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Seo, P.J. Ca2+talyzing Initial Responses to Environmental Stresses. Trends in Plant Science 2021, 26, 849–870. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, L.; Peng, R. Crosstalk between Ca2+ and Other Regulators Assists Plants in Responding to Abiotic Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 1351. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.-Y.; Deisseroth, K.; Tsien, R.W. Activity-Dependent CREB Phosphorylation: Convergence of a Fast, Sensitive Calmodulin Kinase Pathway and a Slow, Less Sensitive Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 2808–2813. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka-Hino, M.; Sagasti, A.; Hisamoto, N.; Kawasaki, M.; Nakano, S.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J.; Bargmann, C.I.; Matsumoto, K. SEK-1 MAPKK Mediates Ca2+ Signaling to Determine Neuronal Asymmetric Development in Caenorhabditis Elegans. EMBO Reports 2002, 3, 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Han, X.; Lu, Z.; Qiu, W.; Yu, M.; Li, H.; He, Z.; Zhuo, R. MAPK Cascades and Transcriptional Factors: Regulation of Heavy Metal Tolerance in Plants. IJMS 2022, 23, 4463. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Y. Plant Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Cascades in Environmental Stresses. IJMS 2021, 22, 1543. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, C. The Function of MAPK Cascades in Response to Various Stresses in Horticultural Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 952. [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qian, L.; Wang, Y.; Cailin, G.; Ding, H. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Action in Plant Response to High-Temperature Stress: A Mini Review. Protoplasma 2021, 258, 477–482. [CrossRef]

- Taj, G.; Agarwal, P.; Grant, M.; Kumar, A. MAPK Machinery in Plants: Recognition and Response to Different Stresses through Multiple Signal Transduction Pathways. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2010, 5, 1370–1378. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).