Submitted:

26 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

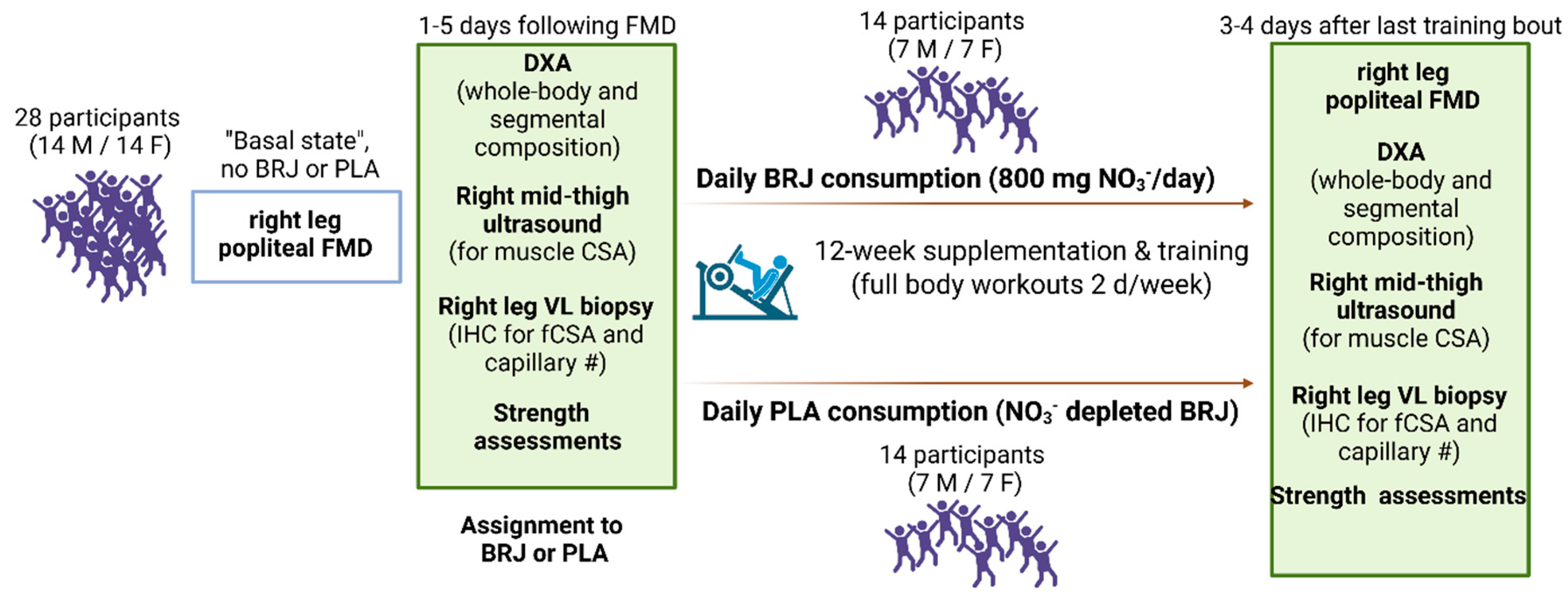

2.1. Ethical Approval, Consent, and Experimental Design

2.2. PRE- and POST-Intervention Blood Pressure and Right Leg Popliteal Artery FMD

2.3. Pre- and Post-Intervention DXA Scans for Body Composition

2.4. Pre- and Post-Intervention Right Mid-Thigh Ultrasonography Assessment

2.5. Pre- and Post-Intervention Right Mid-Thigh VL Biopsies

2.6. Resistance Training Program

2.7. Analyses on Biopsy Specimens

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants, Protocol Adherence, and Missing Data

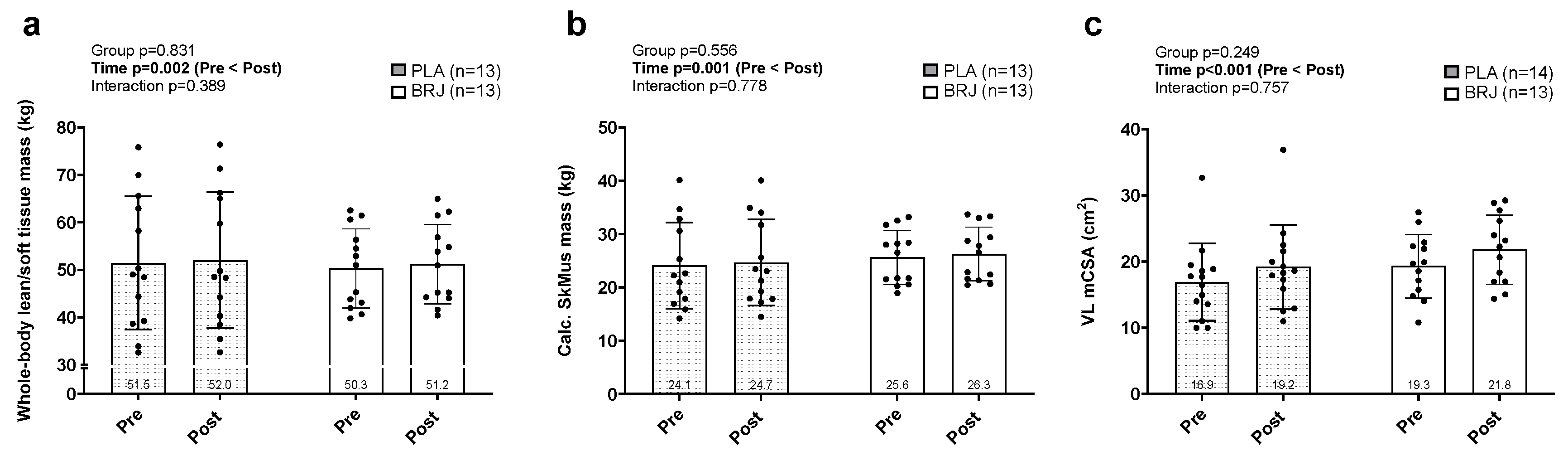

3.2. Whole Body and Mid-Thigh Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophic Outcomes

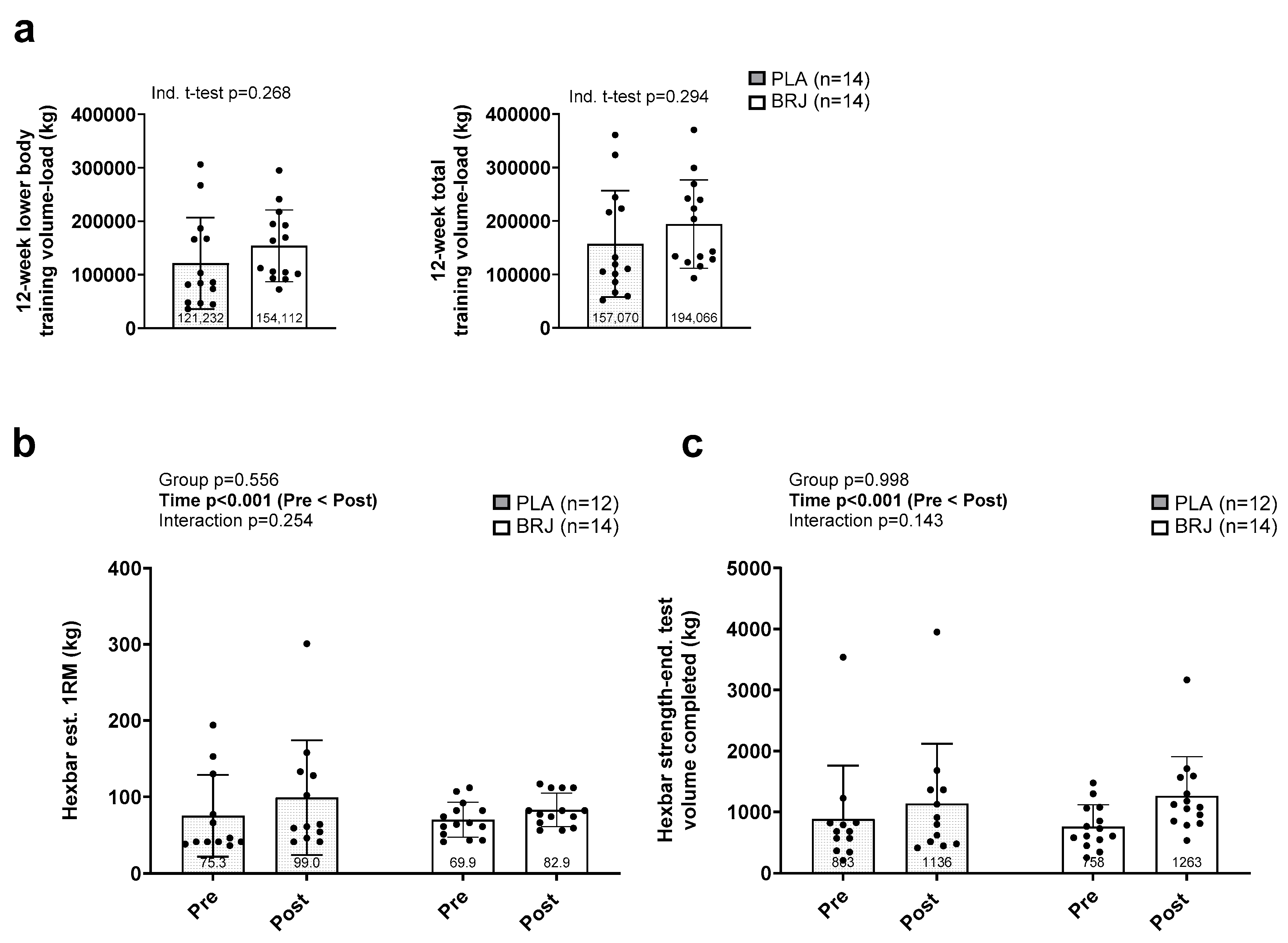

3.3. Strength and Strength-Endurance Outcomes

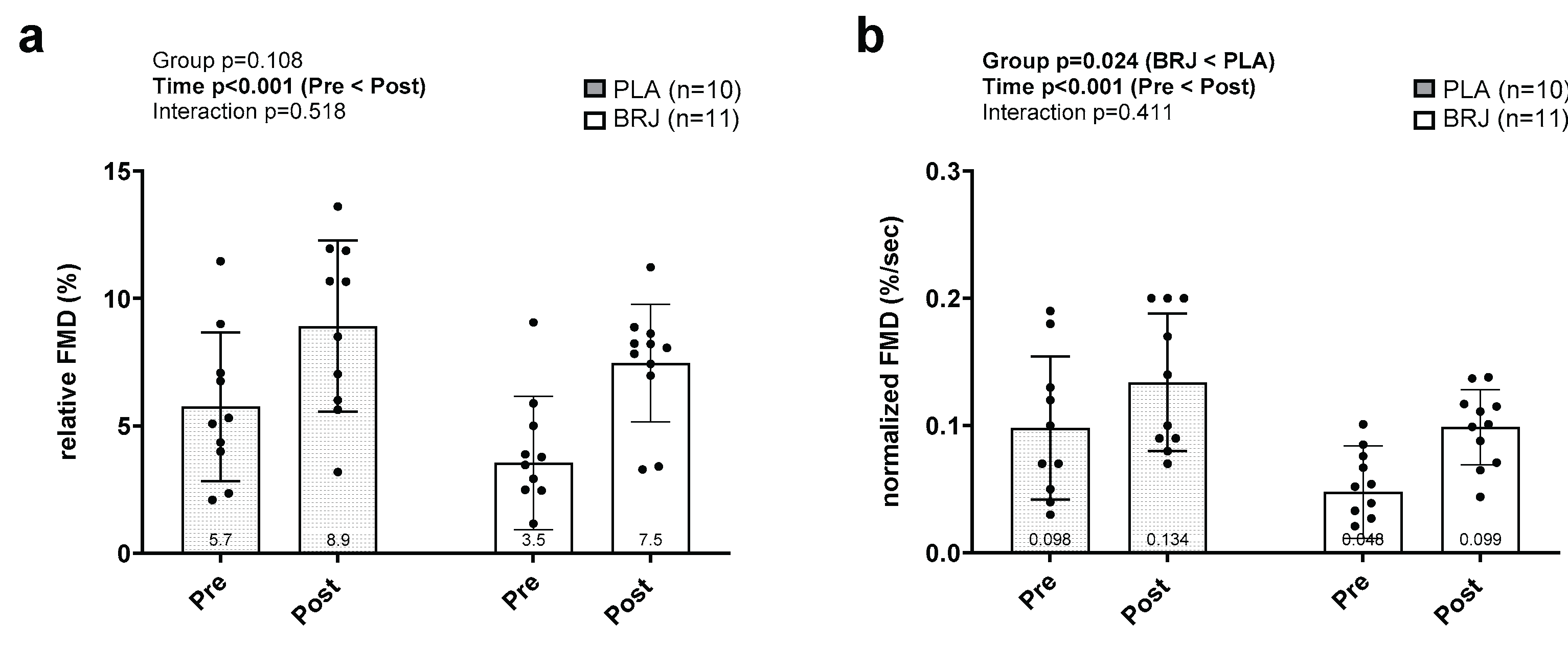

3.4. Popliteal Artery FMD Outcomes

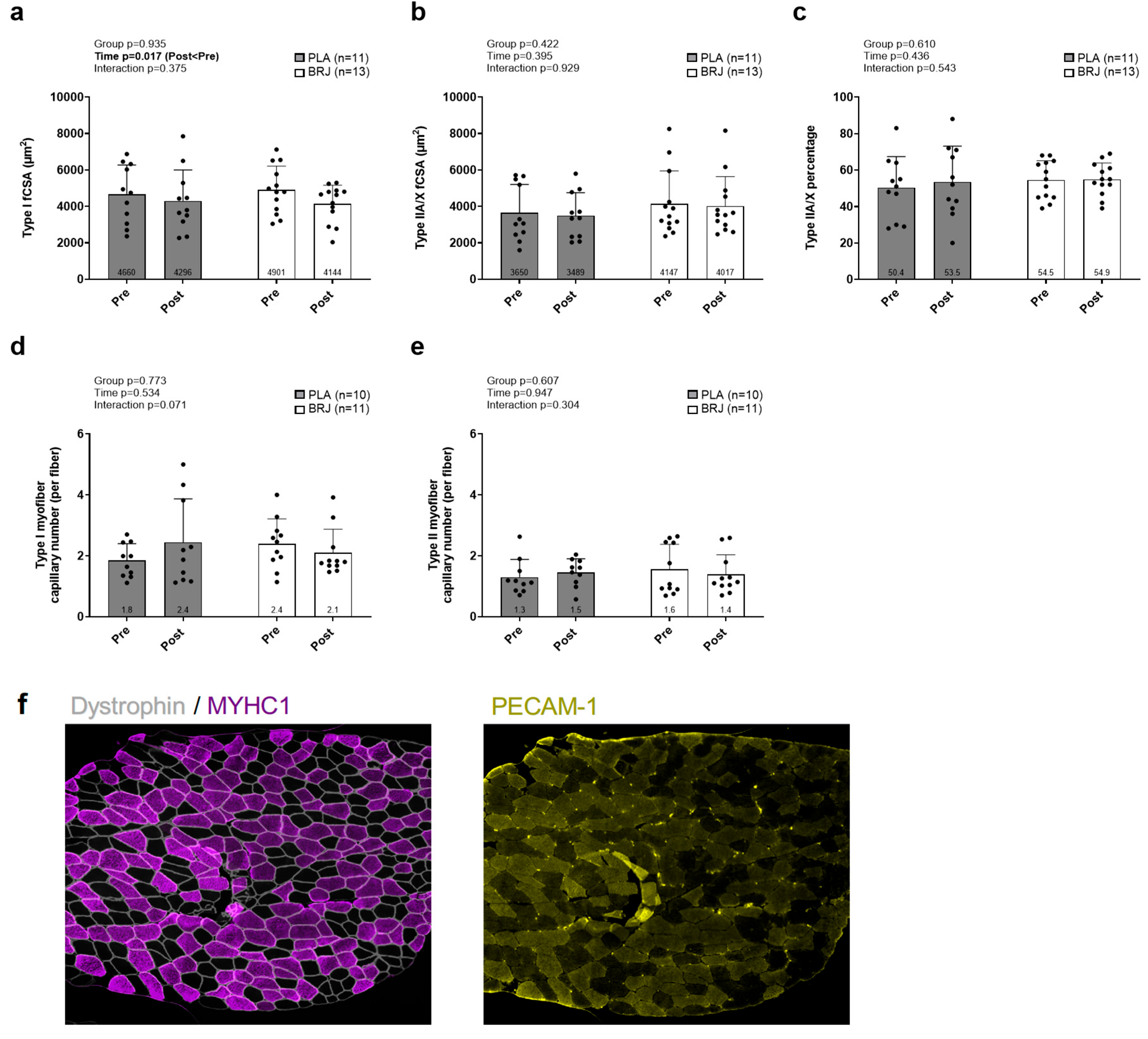

3.5. Fiber Cross-Sectional, Fiber Type, and Skeletal Muscle Capillarization Outcomes

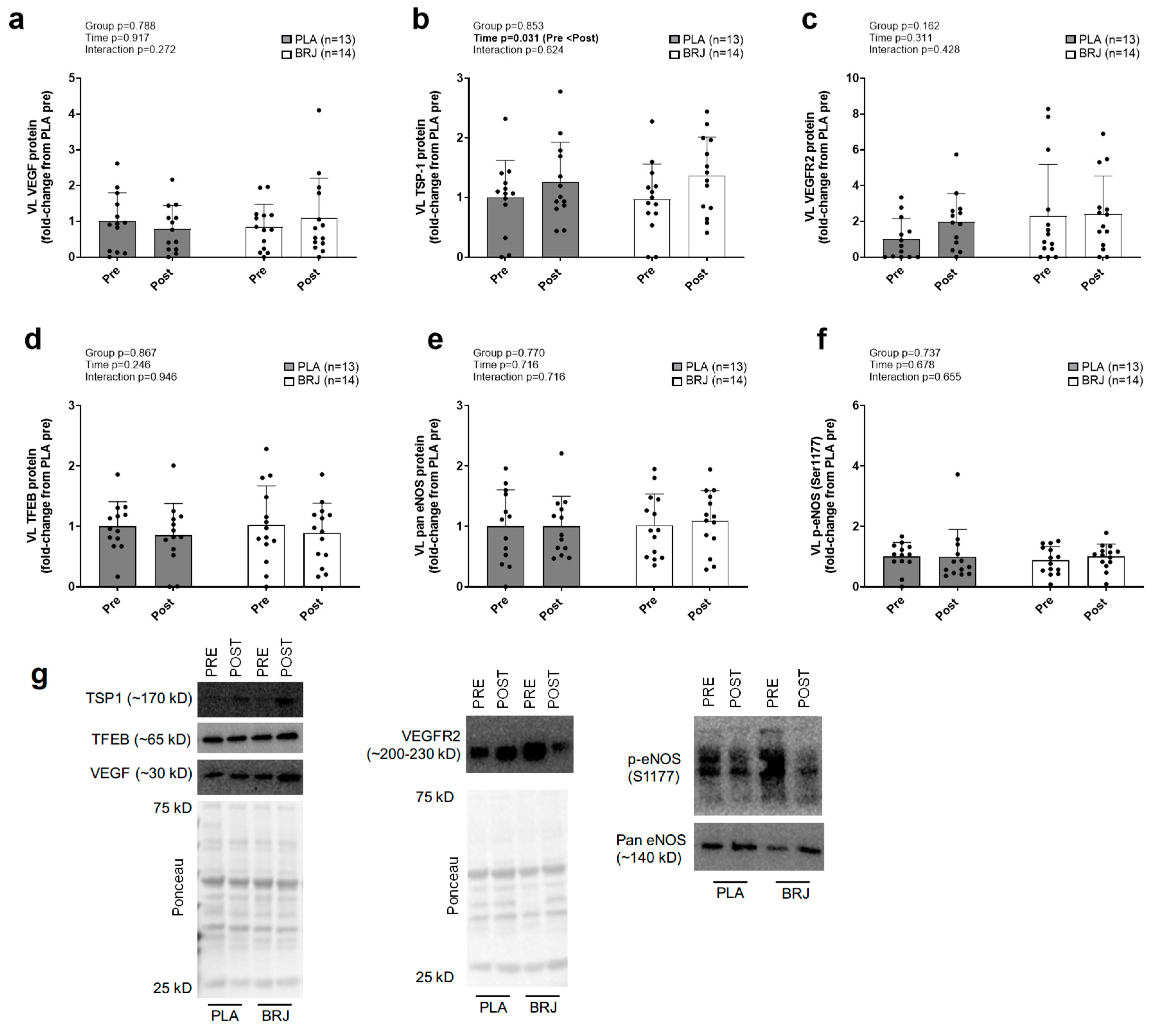

3.6. Immunoblotting Markers and Muscle NOx

3.7. Exploratory Analysis of Sex Effects for Non-FMD Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Considerations

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Troen BR. The biology of aging. Mt Sinai J Med 70: 3-22, 2003.

- Breen L, and Phillips SM. Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in the elderly: Interventions to counteract the 'anabolic resistance' of ageing. Nutr Metab (Lond) 8: 68, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Bell KE, von Allmen MT, Devries MC, and Phillips SM. Muscle Disuse as a Pivotal Problem in Sarcopenia-related Muscle Loss and Dysfunction. J Frailty Aging 5: 33-41, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ruple BA, Mattingly ML, Godwin JS, McIntosh MC, Kontos NJ, Agyin-Birikorang A, Michel JM, Plotkin DL, Chen SY, Ziegenfuss TN, Fruge AD, Gladden LB, Robinson AT, Mobley CB, Mackey AL, and Roberts MD. The effects of resistance training on denervated myofibers, senescent cells, and associated protein markers in middle-aged adults. FASEB J 38: e23621, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Michel JM, Lievense KK, Norton SC, Costa JV, Alphin KH, Bailey LA, and Miller GD. The Effects of Graded Protein Intake in Conjunction with Progressive Resistance Training on Skeletal Muscle Outcomes in Older Adults: A Preliminary Trial. Nutrients 14: 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kosek DJ, Kim JS, Petrella JK, Cross JM, and Bamman MM. Efficacy of 3 days/wk resistance training on myofiber hypertrophy and myogenic mechanisms in young vs. older adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 531-544, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Phillips BE, Williams JP, Greenhaff PL, Smith K, and Atherton PJ. Physiological adaptations to resistance exercise as a function of age. JCI Insight 2: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Shad BJ, Thompson JL, and Breen L. Does the muscle protein synthetic response to exercise and amino acid-based nutrition diminish with advancing age? A systematic review. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 311: E803-E817, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Banks NF, Rogers EM, Church DD, Ferrando AA, and Jenkins NDM. The contributory role of vascular health in age-related anabolic resistance. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13: 114-127, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Morton RW, Traylor DA, Weijs PJM, and Phillips SM. Defining anabolic resistance: implications for delivery of clinical care nutrition. Curr Opin Crit Care 24: 124-130, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Burd NA, Gorissen SH, and van Loon LJ. Anabolic resistance of muscle protein synthesis with aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 41: 169-173, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Haran PH, Rivas DA, and Fielding RA. Role and potential mechanisms of anabolic resistance in sarcopenia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 3: 157-162, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Aragon AA, Tipton KD, and Schoenfeld BJ. Age-related muscle anabolic resistance: inevitable or preventable? Nutr Rev 81: 441-454, 2023.

- Holder SM, Bruno RM, Shkredova DA, Dawson EA, Jones H, Hopkins ND, Hopman MTE, Bailey TG, Coombes JS, Askew CD, Naylor L, Maiorana A, Ghiadoni L, Thompson A, Green DJ, and Thijssen DHJ. Reference Intervals for Brachial Artery Flow-Mediated Dilation and the Relation With Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Hypertension 77: 1469-1480, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Wang B, Ren C, Hu J, Greenberg DA, Chen T, Xie L, and Jin K. Age-related Impairment of Vascular Structure and Functions. Aging Dis 8: 590-610, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Verdijk LB, Snijders T, Holloway TM, J VANK, and LJ VANL. Resistance Training Increases Skeletal Muscle Capillarization in Healthy Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48: 2157-2164, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Dvoretskiy S, Lieblein-Boff JC, Jonnalagadda S, Atherton PJ, Phillips BE, and Pereira SL. Exploring the Association between Vascular Dysfunction and Skeletal Muscle Mass, Strength and Function in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 12: 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yoo JI, Kim MJ, Na JB, Chun YH, Park YJ, Park Y, Hah YS, Ha YC, and Park KS. Relationship between endothelial function and skeletal muscle strength in community dwelling elderly women. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 9: 1034-1041, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Snijders T, Nederveen JP, Joanisse S, Leenders M, Verdijk LB, van Loon LJ, and Parise G. Muscle fibre capillarization is a critical factor in muscle fibre hypertrophy during resistance exercise training in older men. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 8: 267-276, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Moro T, Brightwell CR, Phalen DE, McKenna CF, Lane SJ, Porter C, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB, and Fry CS. Low skeletal muscle capillarization limits muscle adaptation to resistance exercise training in older adults. Exp Gerontol 127: 110723, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Olfert IM, Baum O, Hellsten Y, and Egginton S. Advances and challenges in skeletal muscle angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 310: H326-336, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ryan NA, Zwetsloot KA, Westerkamp LM, Hickner RC, Pofahl WE, and Gavin TP. Lower skeletal muscle capillarization and VEGF expression in aged vs. young men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 100: 178-185, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Croley AN, Zwetsloot KA, Westerkamp LM, Ryan NA, Pendergast AM, Hickner RC, Pofahl WE, and Gavin TP. Lower capillarization, VEGF protein, and VEGF mRNA response to acute exercise in the vastus lateralis muscle of aged vs. young women. J Appl Physiol (1985) 99: 1872-1879, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Endo Y, Hwang CD, Zhang Y, Olumi S, Koh DJ, Zhu C, Neppl RL, Agarwal S, and Sinha I. VEGFA Promotes Skeletal Muscle Regeneration in Aging. Adv Biol (Weinh) 7: e2200320, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AL, and Webster M. Dark Chocolate Elevates Resting Energy Expenditure in Postmenopausal Women. Int J Exerc Sci 18: 316-328, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wageh M, Fortino SA, Pontello R, Maklad A, McGlory C, Kumbhare D, Phillips SM, and Parise G. The Effect of Multi-Ingredient Protein versus Collagen Supplementation on Satellite Cell Properties in Males and Females. Med Sci Sports Exerc 56: 2125-2134, 2024. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh MC, Ruple BA, Kontos NJ, Mattingly ML, Lockwood CM, and Roberts MD. The effects of a sugar-free amino acid-containing electrolyte beverage on 5-kilometer performance, blood electrolytes, and post-exercise cramping versus a conventional carbohydrate-electrolyte sports beverage and water. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 21: 2296888, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mueller BJ, Roberts MD, Mobley CB, Judd RL, and Kavazis AN. Nitric oxide in exercise physiology: past and present perspectives. Front Physiol 15: 1504978, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jones AM. Dietary nitrate supplementation and exercise performance. Sports Med 44 Suppl 1: S35-45, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Lansley KE, Winyard PG, Bailey SJ, Vanhatalo A, Wilkerson DP, Blackwell JR, Gilchrist M, Benjamin N, and Jones AM. Acute dietary nitrate supplementation improves cycling time trial performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43: 1125-1131, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Stanaway L, Rutherfurd-Markwick K, Page R, and Ali A. Performance and Health Benefits of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 9: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Gee LC, and Ahluwalia A. Dietary Nitrate Lowers Blood Pressure: Epidemiological, Pre-clinical Experimental and Clinical Trial Evidence. Curr Hypertens Rep 18: 17, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Williams TD, Martin MP, Mintz JA, Rogers RR, and Ballmann CG. Effect of Acute Beetroot Juice Supplementation on Bench Press Power, Velocity, and Repetition Volume. J Strength Cond Res 34: 924-928, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Zamani H, de Joode M, Hossein IJ, Henckens NFT, Guggeis MA, Berends JE, de Kok T, and van Breda SGJ. The benefits and risks of beetroot juice consumption: a systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 61: 788-804, 2021. [CrossRef]

- McMahon NF, Leveritt MD, and Pavey TG. The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 47: 735-756, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs DA, George TW, and Lovegrove JA. The effects of dietary nitrate on blood pressure and endothelial function: a review of human intervention studies. Nutr Res Rev 26: 210-222, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs DA, Goulding MG, Nguyen A, Malaver T, Walker CF, George TW, Methven L, and Lovegrove JA. Acute ingestion of beetroot bread increases endothelium-independent vasodilation and lowers diastolic blood pressure in healthy men: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr 143: 1399-1405, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Clifford PS, and Hellsten Y. Vasodilatory mechanisms in contracting skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97: 393-403, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Tan R, Pennell A, Price KM, Karl ST, Seekamp-Hicks NG, Paniagua KK, Weiderman GD, Powell JP, Sharabidze LK, Lincoln IG, Kim JM, Espinoza MF, Hammer MA, Goulding RP, and Bailey SJ. Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Performance and Muscle Oxygenation during Resistance Exercise in Men. Nutrients 14: 2022. [CrossRef]

- bold>Carter SJ, Blechschmid TH, Baranauskas MN, Long EB, Gruber AH, Raglin JS, Lim K, and Coggan AR. Preworkout dietary nitrate magnifies training-induced benefits to physical function in late postmenopausal women: a randomized pilot study. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 327: R534-R542, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jones AM, Ferguson SK, Bailey SJ, Vanhatalo A, and Poole DC. Fiber Type-Specific Effects of Dietary Nitrate. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 44: 53-60, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Kolluru GK, Sinha S, Majumder S, Muley A, Siamwala JH, Gupta R, and Chatterjee S. Shear stress promotes nitric oxide production in endothelial cells by sub-cellular delocalization of eNOS: A basis for shear stress mediated angiogenesis. Nitric Oxide 22: 304-315, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Rammos C, Luedike P, Hendgen-Cotta U, and Rassaf T. Potential of dietary nitrate in angiogenesis. World J Cardiol 7: 652-657, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto M, Akishita M, Eto M, Ishikawa M, Kozaki K, Toba K, Sagara Y, Taketani Y, Orimo H, and Ouchi Y. Modulation of endothelium-dependent flow-mediated dilatation of the brachial artery by sex and menstrual cycle. Circulation 92: 3431-3435, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Thijssen DHJ, Bruno RM, van Mil A, Holder SM, Faita F, Greyling A, Zock PL, Taddei S, Deanfield JE, Luscher T, Green DJ, and Ghiadoni L. Expert consensus and evidence-based recommendations for the assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans. Eur Heart J 40: 2534-2547, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Thijssen DH, Black MA, Pyke KE, Padilla J, Atkinson G, Harris RA, Parker B, Widlansky ME, Tschakovsky ME, and Green DJ. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H2-12, 2011.

- Wylie LJ, Kelly J, Bailey SJ, Blackwell JR, Skiba PF, Winyard PG, Jeukendrup AE, Vanhatalo A, and Jones AM. Beetroot juice and exercise: pharmacodynamic and dose-response relationships. J Appl Physiol (1985) 115: 325-336, 2013.

- Siervo M, Lara J, Ogbonmwan I, and Mathers JC. Inorganic nitrate and beetroot juice supplementation reduces blood pressure in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nutr 143: 818-826, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Silva KVC, Costa BD, Gomes AC, Saunders B, and Mota JF. Factors that Moderate the Effect of Nitrate Ingestion on Exercise Performance in Adults: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions. Adv Nutr 13: 1866-1881, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Benjamim CJR, da Silva LSL, Sousa YBA, Rodrigues GDS, Pontes YMM, Rebelo MA, Goncalves LDS, Tavares SS, Guimaraes CS, da Silva Sobrinho AC, Tanus-Santos JE, Gualano B, and Bueno Junior CR. Acute and short-term beetroot juice nitrate-rich ingestion enhances cardiovascular responses following aerobic exercise in postmenopausal women with arterial hypertension: A triple-blinded randomized controlled trial. Free Radic Biol Med 211: 12-23, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Walker MA, Bailey TG, McIlvenna L, Allen JD, Green DJ, and Askew CD. Acute Dietary Nitrate Supplementation Improves Flow Mediated Dilatation of the Superficial Femoral Artery in Healthy Older Males. Nutrients 11: 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hord NG, Tang Y, and Bryan NS. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 1-10, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Wang Z, Heymsfield SB, Baumgartner RN, and Gallagher D. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: estimation by a new dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry method. Am J Clin Nutr 76: 378-383, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Kephart WC, Wachs TD, Thompson RM, Mobley CB, Fox CD, McDonald JR, Ferguson BS, Young KC, Nie B, Martin JS, Company JM, Pascoe DD, Arnold RD, Moon JR, and Roberts MD. Correction to: Ten weeks of branched-chain amino acid supplementation improves select performance and immunological variables in trained cyclists. Amino Acids 50: 1495, 2018.

- Strength N-N, and Association C. Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Human kinetics, 2021.

- Zourdos MC, Klemp A, Dolan C, Quiles JM, Schau KA, Jo E, Helms E, Esgro B, Duncan S, Garcia Merino S, and Blanco R. Novel Resistance Training-Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve. J Strength Cond Res 30: 267-275, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Michel JM, Godwin JS, Plotkin DL, McIntosh MC, Mattingly ML, Agostinelli PJ, Mueller BJ, Anglin DA, Kontos NJ, Berry AC, Vega MM, Pipkin AA, Stock MS, Graham ZA, Baweja HS, Mobley CB, Bamman MM, and Roberts MD. Effects of leg immobilization and recovery resistance training on skeletal muscle-molecular markers in previously resistance-trained versus untrained adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 138: 450-467, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wen Y, Murach KA, Vechetti IJ, Jr., Fry CS, Vickery C, Peterson CA, McCarthy JJ, and Campbell KS. MyoVision: software for automated high-content analysis of skeletal muscle immunohistochemistry. J Appl Physiol (1985) 124: 40-51, 2018. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh MC, Michel JM, Godwin JS, Plotkin DL, Anglin DA, Mattingly ML, Agyin-Birikorang A, Kontos NJ, Baweja HS, Stock MS, Mobley CB, and Roberts MD. Disuse and subsequent recovery resistance training affect skeletal muscle angiogenesis related markers regardless of prior resistance training experience. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lawler PR, and Lawler J. Molecular basis for the regulation of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 and -2. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2: a006627, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Doronzo G, Astanina E, Cora D, Chiabotto G, Comunanza V, Noghero A, Neri F, Puliafito A, Primo L, Spampanato C, Settembre C, Ballabio A, Camussi G, Oliviero S, and Bussolino F. TFEB controls vascular development by regulating the proliferation of endothelial cells. EMBO J 38: 2019. [CrossRef]

- Carlstrom M, Liu M, Yang T, Zollbrecht C, Huang L, Peleli M, Borniquel S, Kishikawa H, Hezel M, Persson AE, Weitzberg E, and Lundberg JO. Cross-talk Between Nitrate-Nitrite-NO and NO Synthase Pathways in Control of Vascular NO Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal 23: 295-306, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Coggan AR, Hoffman RL, Gray DA, Moorthi RN, Thomas DP, Leibowitz JL, Thies D, and Peterson LR. A Single Dose of Dietary Nitrate Increases Maximal Knee Extensor Angular Velocity and Power in Healthy Older Men and Women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 75: 1154-1160, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Barkhidarian B, Khorshidi M, Shab-Bidar S, and Hashemi B. Effects of L-citrulline supplementation on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Avicenna J Phytomed 9: 10-20, 2019.

- Maharaj A, Fischer SM, Dillon KN, Kang Y, Martinez MA, and Figueroa A. Effects of L-Citrulline Supplementation on Endothelial Function and Blood Pressure in Hypertensive Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 14: 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kang Y, Dillon KN, Martinez MA, Maharaj A, Fischer SM, and Figueroa A. L-Citrulline Supplementation Improves Arterial Blood Flow and Muscle Oxygenation during Handgrip Exercise in Hypertensive Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 16: 2024. [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Garcia A, Pascual-Fernandez J, Noriega-Gonzalez DC, Bello HJ, Pons-Biescas A, Roche E, and Cordova-Martinez A. L-Citrulline Supplementation and Exercise in the Management of Sarcopenia. Nutrients 13: 2021. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Parker JR, Strahler TR, Bassett CJ, Bispham NZ, Chonchol MB, and Seals DR. Curcumin supplementation improves vascular endothelial function in healthy middle-aged and older adults by increasing nitric oxide bioavailability and reducing oxidative stress. Aging (Albany NY) 9: 187-208, 2017.

- Holloway TM, Snijders T, J VANK, LJC VANL, and Verdijk LB. Temporal Response of Angiogenesis and Hypertrophy to Resistance Training in Young Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50: 36-45, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gavin TP, Drew JL, Kubik CJ, Pofahl WE, and Hickner RC. Acute resistance exercise increases skeletal muscle angiogenic growth factor expression. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 191: 139-146, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kim HB, Seo MW, and Jung HC. Effects of Aerobic vs. Resistance Exercise on Vascular Function and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Older Women. Healthcare (Basel) 11: 2023. [CrossRef]

- Fry AC. The role of resistance exercise intensity on muscle fibre adaptations. Sports Med 34: 663-679, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Ruple BA, Mesquita PHC, Godwin JS, Sexton CL, Osburn SC, McIntosh MC, Kavazis AN, Libardi CA, Young KC, and Roberts MD. Changes in vastus lateralis fibre cross-sectional area, pennation angle and fascicle length do not predict changes in muscle cross-sectional area. Exp Physiol 107: 1216-1224, 2022.

- Toth MJ, Miller MS, VanBuren P, Bedrin NG, LeWinter MM, Ades PA, and Palmer BM. Resistance training alters skeletal muscle structure and function in human heart failure: effects at the tissue, cellular and molecular levels. J Physiol 590: 1243-1259, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Babcock MC, DuBose LE, Witten TL, Brubaker A, Stauffer BL, Hildreth KL, and Moreau KL. Assessment of macrovascular and microvascular function in aging males. J Appl Physiol (1985) 130: 96-103, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Capper TE, Siervo M, Clifford T, Taylor G, Iqbal W, West D, and Stevenson EJ. Pharmacokinetic Profile of Incremental Oral Doses of Dietary Nitrate in Young and Older Adults: A Crossover Randomized Clinical Trial. J Nutr 152: 130-139, 2022. [CrossRef]

- McManus CJ, Collison J, and Cooper CE. Performance comparison of the MOXY and PortaMon near-infrared spectroscopy muscle oximeters at rest and during exercise. J Biomed Opt 23: 1-14, 2018. [CrossRef]

| Antibody | Host species (isotype) | Company (Cat. No.) |

| Western blotting | ||

| VEGF | Rb | Cell Signaling (65373) |

| VEGFR2 | Rb | Cell Signaling (9698) |

| TSP-1 | Rb | Cell Signaling (37879) |

| TFEB | Rb | Cell Signaling (83010) |

| eNOS | Rb | Cell Signaling (32027) |

| Phospho-eNOS (Ser1177) | Rb | Cell Signaling (9507) |

| Anti-Rb IgG, HRP-conjugated | G | Cell Signaling (7074) |

| Immunohistochemistry | ||

| CD31/PECAM-1 | M (IgG1) | DSHB (P2B1) |

| Type I myosin heavy chain | M (IgG2b) | DSHB (BA-D5) |

| Dystrophin | Rb (IgG) | Abcam (ab218198) |

| Anti-M IgG1, AF555-conjugated | G | Thermo Fisher (A-21127) |

| Anti-M IgG2b, AF488-conjugated | G | Thermo Fisher (A-21141) |

| Anti-Rb IgG, AF647-conjugated | G | Thermo Fisher (A-21245) |

| Variable | BRJ (n=14) | PLA (n=14) | Ind. t-test p-value |

| Age (years) | 56±6 | 56±7 | 1.000 |

| Sex | 7 M / 7 F | 7 M / 7 F | 1.000 |

| Height (cm) | 174±8 | 172±13 | 0.685 |

| Body mass (kg) | 87.3±16.9 | 85.1±25.1 | 0.788 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4±5.6 | 28.9±5.1 | 0.788 |

| Hex bar est. 1-RM | 70.0±22.8 | 75.2±53.7 | 0.741 |

| Variable | BRJ | PLA | p-values | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | Pre: 61 ± 6 Post: 66 ± 9 |

Pre: 65 ± 7 Post: 73 ± 25 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.061 0.472 0.587 0.317 |

| SBP (mmHg) | Pre: 126 ± 13 Post: 131 ± 17 |

Pre: 128 ± 19 Post: 128 ± 19 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.400 0.460 0.420 0.795 |

| DBP (mmHg) | Pre: 80 ± 6 Post: 81 ± 8 |

Pre: 83 ± 10 Post: 83 ± 13 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.681 0.082 0.506 0.918 |

| MAP (mmHg) | Pre: 111 ± 10 Post: 114 ± 13 |

Pre: 113 ± 16 Post: 113 ± 17 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.424 0.356 0.442 0.837 |

| Baseline Diam. (mm) | Pre: 6.28 ± 1.31 Post: 6.25 ± 1.31 |

Pre: 6.19 ± 1.42 Post: 5.82 ± 1.49 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.723 0.738 0.488 0.476 |

| Average Shear Rate (s⁻¹) |

Pre: 44.4 ± 19.0 Post: 39.1 ± 17.6 |

Pre: 49.4 ± 22.8 Post: 44.3 ± 17.3 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.210 0.950 0.805 0.944 |

| Peak Shear Rate (s⁻¹) |

Pre: 67.1 ± 22.1 Post: 77.8 ± 22.8 |

Pre: 62.8 ± 9.7 Post: 65.9 ± 13.8 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.004 0.659 0.599 0.762 |

| Shear Rate Area Under the Curve (AU) | Pre: 6275 ± 2046 Post: 7000 ± 2054 |

Pre: 5228 ± 1858 Post: 5929 ± 1238 |

Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.005 0.959 0.987 0.494 |

| FMD (%) | Data presented in Figure 4 | Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.001 0.844 0.327 0.151 |

|

| Normalized FMD (%) |

Data presented in Figure 4 | Time Sex × time Supplement × time Sex × supplement × time |

0.001 0.699 0.279 0.211 |

|

| Variable | BRJ & PLA F/M | Stats |

| DXA lean tissue mass | BRJ: 7F/6M PLA: 7F/6M |

Sex p<0.001 (M>F) Sex × time p=0.478 Sex × supplement × time p = 0.615 |

| VL mCSA | BRJ: 6F/7M PLA: 7F/7M |

Sex p=0.021 (M>F) Sex × time p=0.074 Sex × supplement × time p = 0.456 |

| Hex bar est. 1-RM | BRJ: 6F/7M PLA: 7F/7M |

Sex p<0.001 (M>F) Sex × time p=0.119 Sex × supplement × time p = 0.106 |

| Hex bar strength-end. test | BRJ: 6F/7M PLA: 7F/5M |

Sex p<0.001 (M>F) Sex × time p=0.176 Sex × supplement × time p = 0.492 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).