Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a ubiquitous molecule involved in many cellular functions. The depletion of NO is implicated in cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, neurodegenerative disease, and maladies associated with the metabolic syndrome (Litvinova et al., 2015; Naseem, 2005; Snyder, 1992; Soodaeva et al., 2020). With such extensive involvement in human health, it is not surprising that researchers have sought to reveal the functions, mechanisms, and positive or negative effects of the depletion or abundance of NO in the human body.

Though it is most readily recognized for its role in vasodilation, NO is also involved in skeletal muscle contractility, mitochondrial function, and redox state (Mueller et al., 2024). Several reports have described the role of NO during exercise (Jones, 2014; Jones et al., 2021; F. J. Larsen et al., 2007; McMahon et al., 2017; Tan, Baranauskas, et al., 2023), with beetroot juice serving as a functional medium for nitrate supplementation. Investigation of nitrate supplementation and exercise has primarily focused on acute doses and endurance exercise. In this regard, two meta-analyses have indicated that acute nitrate supplementation confer small-to-moderate improvements in time to exhaustion and time trial performance (Hoon et al., 2013; McMahon et al., 2017). In contrast, nitrate supplementation has been less investigated in the context of resistance exercise. Preliminary findings suggest that acute nitrate supplementation with resistance exercise mirrors effects observed with endurance exercise and similarly improves exercise tolerance via increasing repetitions to failure (Mosher et al., 2016). Moreover, a recent study by Carter et al. examined the effects of beet root juice supplementation on performance outcomes in postmenopausal women who engaged in 8 weeks of circuit training (Carter et al., 2024). Notably, one group consumed 140 mL per day (~13 mmol nitrates) for the first 7 weeks of the study, while the other group did not engage in supplementation. Interestingly, nitrate supplementation elicited large effects on increases in maximal knee extensor power and aerobic capacity. However, the aforementioned study was open label and potential mechanisms of action were not elucidated.

It is well established that chronic resistance training improves muscular strength, muscular endurance, and skeletal muscle mass (Roberts et al., 2023). These improvements are predominantly caused by increases in myofibrillar content, increased myofiber size, and neural adaptations (Furrer et al., 2023). Resistance training has also been shown to stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis, particularly in older individuals (Parry et al., 2020). Critically, this latter adaptation is beneficial to older individuals who typically possess reductions in mitochondrial function (Kedlian et al., 2024). Although nitrates have been implicated in enhancing aspects of mitochondrial biogenesis and function, there are potential concerns with nitrates facilitating increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, especially in older individuals (Fan et al., 2014; Mueller et al., 2024). We recently conducted a double-blinded placebo-controlled study indicating that 12 weeks of beetroot juice supplementation (providing ~13 mmol nitrates/day) did not enhance resistance training adaptations in older individuals (McIntosh et al., 2025). The targeted outcomes in that study included whole-body skeletal muscle mass, vastus lateralis muscle cross-sectional area (CSA), myofiber CSA, and maximal lower body strength. However, mitochondrial markers or redox outcomes were not assessed, and various aspects of strength-endurance were not reported. Therefore, the purpose of this follow-up study was to determine if 12 weeks of nitrate supplementation with resistance training affected the following outcomes affected: i) markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling, ii) antioxidant protein levels and markers of oxidative damage, and iii) strength-endurance measures of the leg extensors assessed using isokinetic dynamometry. Compared to a group who supplemented daily with nitrate-free beet root juice (i.e., placebo), we hypothesized that those engaged in nitrate supplementation would experience increases in skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling. We additionally hypothesized that nitrate supplementation would increase skeletal muscle antioxidants and reduce oxidative damage. Finally, we hypothesized that nitrate supplementation would enhance aspects of strength-endurance.

Methods

Ethical Approval and Participants

The study herein was conducted following review and approval from the Auburn University Institutional Review Board and is in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki (IRB approval number 24-863). Participants recruited and admitted to the study were untrained, defined as having no or minimal experience participating in aerobic or resistance exercise more than once per week during the year prior to participation in the study. Exclusion criteria were: i) having consumed ergogenic aids one month prior to the start of the study including supplements containing beetroot juice, L-citrulline, L-arginine, and creatine, ii) having blood clotting issues precluding muscle biopsies, iii) being allergic to lidocaine or supplement contents in beetroot juice or Placebo, iv) having musculoskeletal impairments or past injuries precluding participation in resistance training, v) having medical issues precluding participation in resistance training. Before participating in the study, each participant met with laboratory personnel to review the requirements, risks, and benefits of the study. After completing pre-screening and providing verbal and written consent, 28 qualified participants were admitted to and completed the study. However, one participant was unable to complete isokinetic dynamometer testing and tissue limitations were evident for four participants. Hence, 27 participants (13 M, 14 F) were included in the current isokinetic dynamometer analysis, and 24 participants (12 M, 12 F) were included for biochemical analysis.

Study Design

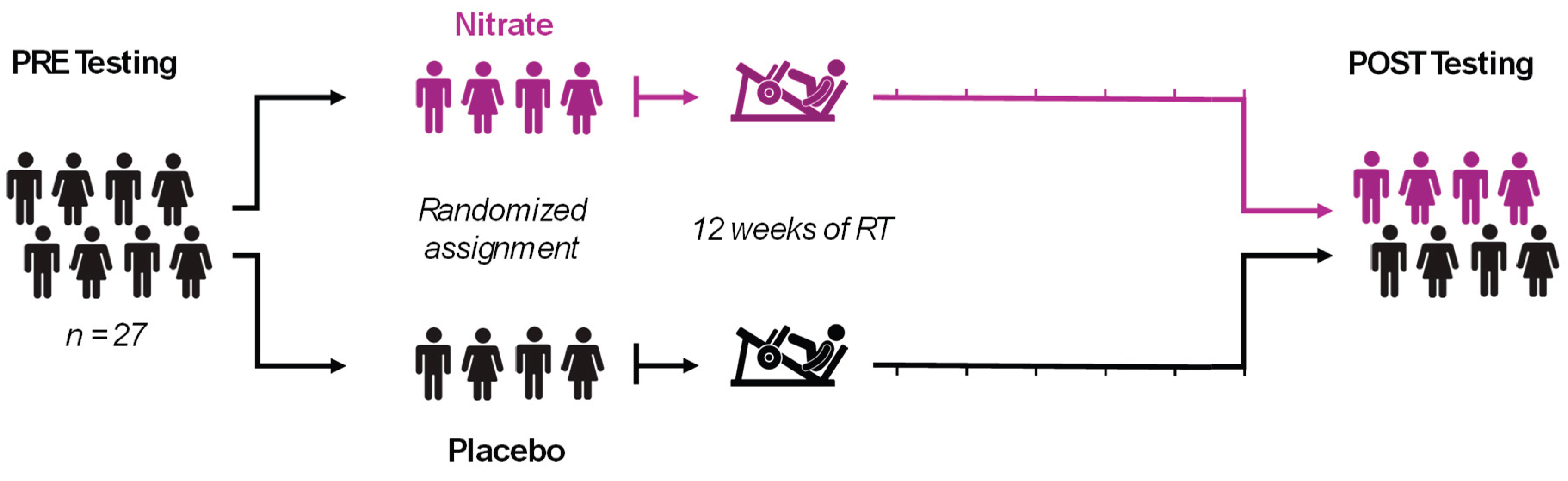

Following pre-intervention (PRE) testing, participants were block-randomized by sex (male and female) and PRE lean body mass measured by whole-body dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (above and below median within sex) to either the Placebo group or Nitrate supplementation group. Participants engaged in physiological assessments on two occasions: PRE and post-intervention (POST) testing. For each testing session, participants arrived following a ≥4 hour fasting session. Each testing session was completed within the same time of day for each participant. Beginning 3-6 days after PRE testing, participants completed 12 weeks of total body resistance training twice per week while consuming daily doses of either a nitrate-free beet root juice (Placebo) or nitrate-rich beetroot juice supplement until one day prior to POST testing. POST testing was conducted ~3 days following the final resistance training session and testing measures and conditions were identical to PRE testing (

Figure 1).

Resistance Training

Participants completed 12 weeks of total body RT performed twice per week on either Mondays/Wednesdays or Tuesdays/Fridays (

Table 1). Exercises completed in each workout included hex bar deadlifts, 45º leg press, seated leg extensions, lying hamstring curls, machine chest press and cable pulldowns. Training sessions were supervised by laboratory personnel with prior experience in instructing exercise techniques, and who were able to ensure proper form and intensity were achieved safely. Intensity was monitored using repetitions in reserve (RIR) as described by Zourdos et al. (Zourdos et al., 2016). Participant RIR was recorded after every set of exercise and adjustments in load were made to achieve an RIR of 0-2. If RIR was >2, the load was increased by an additional ~4.5-9 kg (10-20 pounds) for lower-body exercises and ~2.3-4.5 kg (5-10 pounds) for upper-body exercises. If participants were unable to complete the prescribed number of repetitions, the load was decreased by ~4.5-9 kg (10-20 pounds) for lower-body exercises and ~2.3-4.5 kg (5-10 pounds) for upper-body exercises. The training program utilized linear progression where load was increased, and volume was decreased throughout the 12-week period. Note that no participant was excluded from the study due to exercise adherence, which was predetermined to be ≥4 workouts over the 12-week intervention.

Nitrate Supplementation

Participants were instructed to consume the Placebo or Nitrate supplement daily throughout the duration of the 12-week training period with supplementation beginning on the first day of training. On rest days, participants were instructed to consume their assigned supplement during the morning hours. On training days, participants were instructed to consume their supplement two hours prior to their session. The supplemental dosage was two shots (140 mL) of either the nitrate-depleted Placebo (~0.08 mmol nitrate; Beet It, James White Drinks, Ipswich, UK) or a nitrate-rich beetroot juice (~12.8 mmol nitrate; Beet It, James White Drinks, Ipswich, UK). Participants received weekly allocations of supplements in identical bottles. Although the bottles themselves were indistinguishable, the shipping cases contained labeling that identified the contents as either nitrate-rich or nitrate-depleted. To maintain double blinding, a laboratory technician not involved in data collection or participant interaction removed the bottles from their shipping cases and placed them in unmarked bags prior to distribution to participants.

PRE/POST Testing Measures

Anthropometrics, DXA and Ultrasound. Upon arrival, participant height and body mass were measured using a digital scale (Seca 769; Hanover, MD, USA). Next, DXA (Lunar Prodigy; GE Corporation, Fairfield, CT, USA) was performed to determine whole-body lean body mass, fat mass, and body fat percentage. Following the DXA scan, real-time B-mode ultrasonography (NextGen LOGIQe R8, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to determine the thickness of the vastus lateralis (VL) of the right leg as previously described by our laboratory (Ruple, Mesquita, et al., 2022; Ruple, Smith, et al., 2022). Measurements were taken at the midway point between the iliac crest and proximal patella (Mesquita et al., 2023). Note, all these data were previously analyzed and reported by McIntosh et al. (McIntosh et al., 2025).

Muscle biopsies and tissue processing. Skeletal muscle samples were collected from the vastus lateralis (VL) of the right leg via skeletal muscle biopsy as previously described by our laboratory (Kephart et al., 2015). Briefly, muscle biopsies were taken midway between the patella and iliac crest using a 5-gauge Bergstrom needle. Biopsies at POST were obtained approximately 2 cm proximally of each preceding biopsy scar. Participants lay supine on an athletic training table, and the upper thigh was shaven and cleaned with 70% isopropanol before receiving a 0.8 mL injection of 1% lidocaine. Participants rested for 5–10 minutes to allow the lidocaine to take effect before the area was cleaned with chlorhexidine and a pilot incision through the dermis was made with a sterile No. 11 surgical blade (AD Surgical; Sunnyvale CA, USA). Approximately 50–100 mg of skeletal muscle tissue was collected, immediately teased of blood and connective tissue, and separated for biochemical analysis. From this sample, ~20–40 mg of tissue was placed in pre-labelled foil and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for the Western Blotting and biochemical analyses described below. Notably, removal of tissue and all tissue processing occurred within a 5-minute period (Mesquita et al., 2023).

Muscular strength, power and endurance testing. Following the biopsy procedure, two concentric isokinetic knee extension tests were performed on a BioDex 4.0 (BioDex Medical Systems; Shirley, New York, USA) and utilized to assess muscular strength, power and strength-endurance. Participants were secured in the BioDex seat with straps across the chest, midsection and left thigh. The left lateral femoral condyle of the knee was aligned to the fulcrum of the dynamometer, and the resistance pad was secured proximally to the medial malleolus. Chair position measurements were recorded at PRE testing and replicated at POST testing to ensure identical testing conditions. Participants were instructed to brace themselves only by tucking their thumbs under their chest straps and to flex and extend their leg as hard as possible for each repetition of each test. Five minutes of passive recovery were given between tests. Before beginning the tests, participants performed 5 leg extensions for familiarization. The first test consisted of 6 leg extensions (6LE) against a fixed rotational velocity of 90 degrees per second. The second test consisted of 30 leg extensions (30LE) against a fixed rotational velocity of 180 degrees per second.

Strength testing. Participants then completed a strength assessment consisting of a five-repetition maximum (5RM) test for Hex-bar deadlift. Following a standardized warm up and instruction of exercise technique, participants completed one warm up set of 10 reps with an unloaded hex bar, one warm up set of 5 reps at an estimated 50% 5RM, and a final warm up set of 5 reps at an estimated 75% 5RM before attempting their 5RM. Starting load for the first 5RM attempt was self-selected, and adjustments thereafter were made in ~2.3-4.5-kg (or 5-10-lb) increments. 5RM values were determined when participants could not increase in weight while maintaining correct technique. Again, these strength testing data were previously analyzed and reported by McIntosh et al. (McIntosh et al., 2025).

Biochemical Analyses

Protein isolation. Approximately 30 mg of muscle tissue that was flash-frozen in foil was retrieved from −80°C, weighed using an analytical scale, and homogenized in 1.7 mL tubes using a general cell homogenization buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; Cat no: 9803) using tight-fitting hard-plastic microtube pestles on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 800 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and supernatants were removed and placed in new 1.7 mL tubes. Protein concentrations from the resulting supernatants were determined using a commercially available BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Supernatants were then used for citrate synthase (CS) activity and western blotting.

Western blotting. Muscle supernatants were prepared for Western blotting using 4x Laemmli buffer and deionized water (diH2O) at equal protein concentration (1 µg/µL). Samples (10 μL) were pipetted onto SDS-PAGE gels (4%–15% Criterion TGX Stain-free gels; Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercules, CA, USA), and proteins were separated by electrophoresis (200 V for approximately 40 minutes). Proteins were then transferred to preactivated PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 2 hours at 200 mA. Gels were then Ponceau stained for 5 minutes, washed with diH2O for 30 seconds, dried, and digitally imaged (ChemiDoc Touch, Bio-Rad). Following Ponceau imaging, membranes were reactivated in methanol, blocked with nonfat bovine milk for 1 hour, washed three times in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with primary antibodies overnight (1:1000 v/v dilution in TBST with 5% BSA). See

Table 2 for a list of primary and secondary antibodies used to detect proteins of interest. Membranes were then washed in TBST, developed using chemiluminescent substrate (Millipore; Burlington, MA, USA), and digitally imaged. Raw target band densities were obtained and normalized by Ponceau densitometry values. Additionally, gel-to-gel correction values were applied, wherein overall intensities for gels were normalized to increase comparative efficacy.

Citrate synthase activity. Tissue lysates obtained through cell lysis buffer processing (described above) were batch processed for citrate synthase activity as previously described by our laboratory (Kephart et al., 2015; Mesquita et al., 2023; Ruple, Godwin, Mesquita, Osburn, Sexton, et al., 2021). This metric was used as a surrogate for mitochondrial content per the findings of Larsen et al. (2012) suggesting citrate synthase activity highly correlates with transmission electron micrograph (TEM) images of mitochondrial content (r = 0.84, p < 0.001) (S. Larsen et al., 2012). The assay principle is based upon the reduction of 5,50-dithiobis (2- nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) at 412 nm (extinction coefficient 13.6 mmol/L/cm) coupled to the reduction of acetyl-CoA by the citrate synthase reaction in the presence of oxaloacetate. Briefly, 5 μg of skeletal muscle protein was added to a mixture composed of 0.125 mol/L Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 0.03 mmol/L acetyl-CoA, and 0.1 mmol/L DTNB. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 5 μL of 50 mmol/L oxaloacetate and the absorbance change was recorded for 1 min. The average CV values for all duplicates was 1.1%.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in Jamovi v2.3.28, and graphs were constructed in Prism v10. Data were assessed for normality, homogeneity of variance and sphericity. The Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to dependent variables which violated the sphericity assumption. Repeated measures two-way ANOVAs (group x time) were used to investigate the effect of Nitrate supplementation on functional measures and molecular markers. The sphericity assumption of all dependent variables was tested using Mauchly’s Test of Sphericity. Post hoc analyses were performed using Tukey tests when ANOVA interactions reached statistical significance. Statistical significance was established at p < 0.05 and all data reported are displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) values throughout. Eta-squared values (ƞp2) are also presented as effect sizes for all outcome variables.

Results

General Effects of Supplementation and Training Outcomes

General effects of supplementation have been reported by McIntosh et al. (McIntosh et al., 2025) but are provided in-text for convenience to the reader. Two-way ANOVAs indicated significant main effects of time where POST was greater than PRE for DXA-derived whole-body bone-free lean tissue mass (+1.5% for all 28 participants, p = 0.002), vastus lateralis muscle cross-sectional area (+10.8% for all 28 participants, p < 0.001), and estimated Hexbar deadlift strength (+31.4% for all 28 participants, p < 0.001). However, no group x time interactions were evident for these variables (interaction p-values = 0.389, 0.757, and 0.254, respectively). Independent t-tests also indicated that no significant differences existed between supplement groups for 12-week total-body training volume (p = 0.294) or lower-body training volume (p = 0.268). Finally, although no significant interaction existed for muscle NOx (nitrates + nitrates) concentrations (p = 0.272), forced post hocs indicated that values trended upward from PRE to POST in the Nitrate group (+15.4%, p = 0.073), whereas this statistical trend was not evident in the Placebo group (+7.0%, p = 0.514).

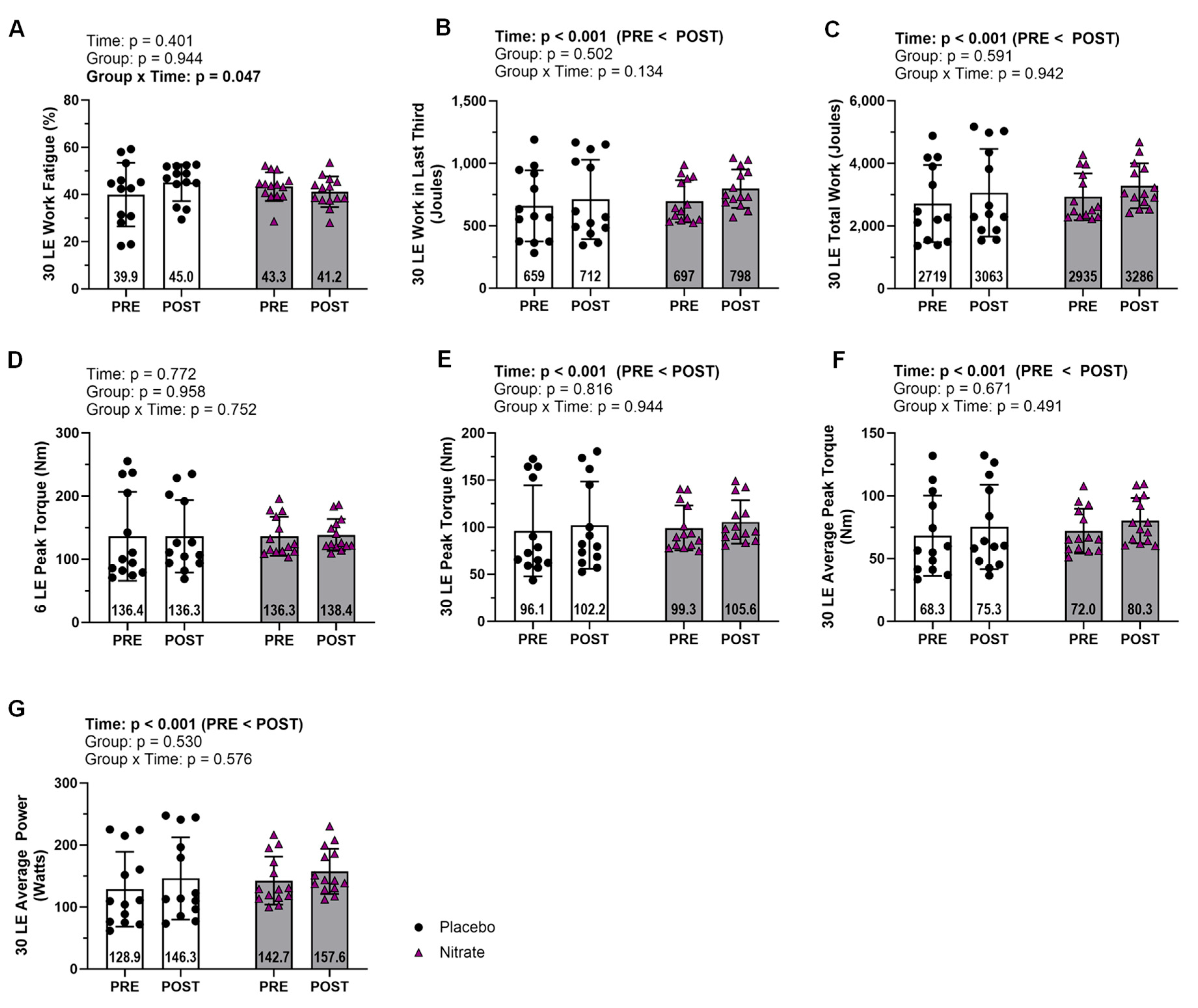

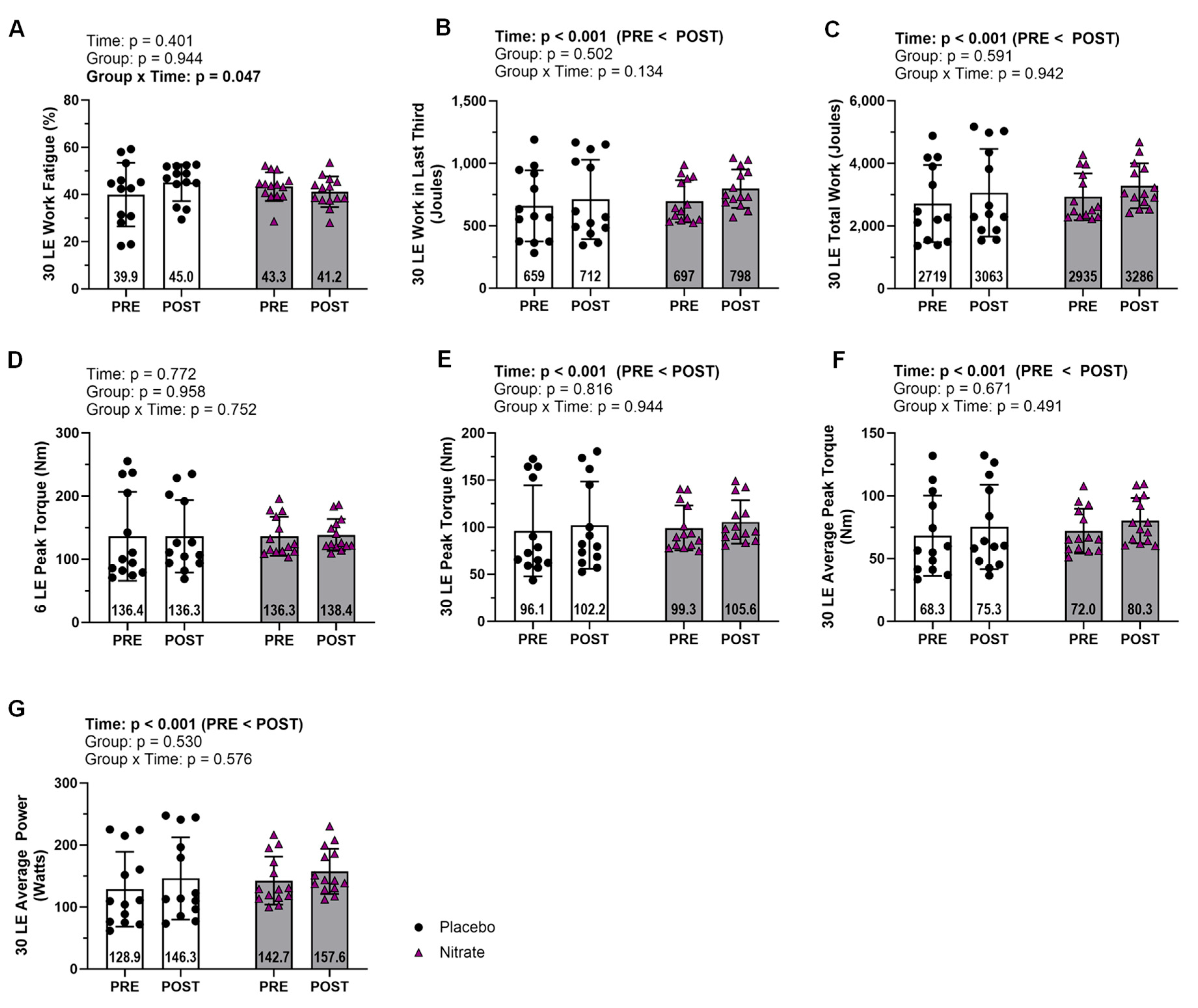

Knee Extensor Strength-Endurance and Power Outcomes

There were no significant group x time interactions present for any left leg knee extensor isokinetic dynamometry outcome (p > 0.05) except for work fatigue (ƞ

p2 = 0.149; p = 0.047;

Figure 2A) which is a measure of muscular endurance. However, significant between- or within-group effects were observed. All other measures except for 6LE peak torque exhibited a main effect of time where POST was greater than PRE.

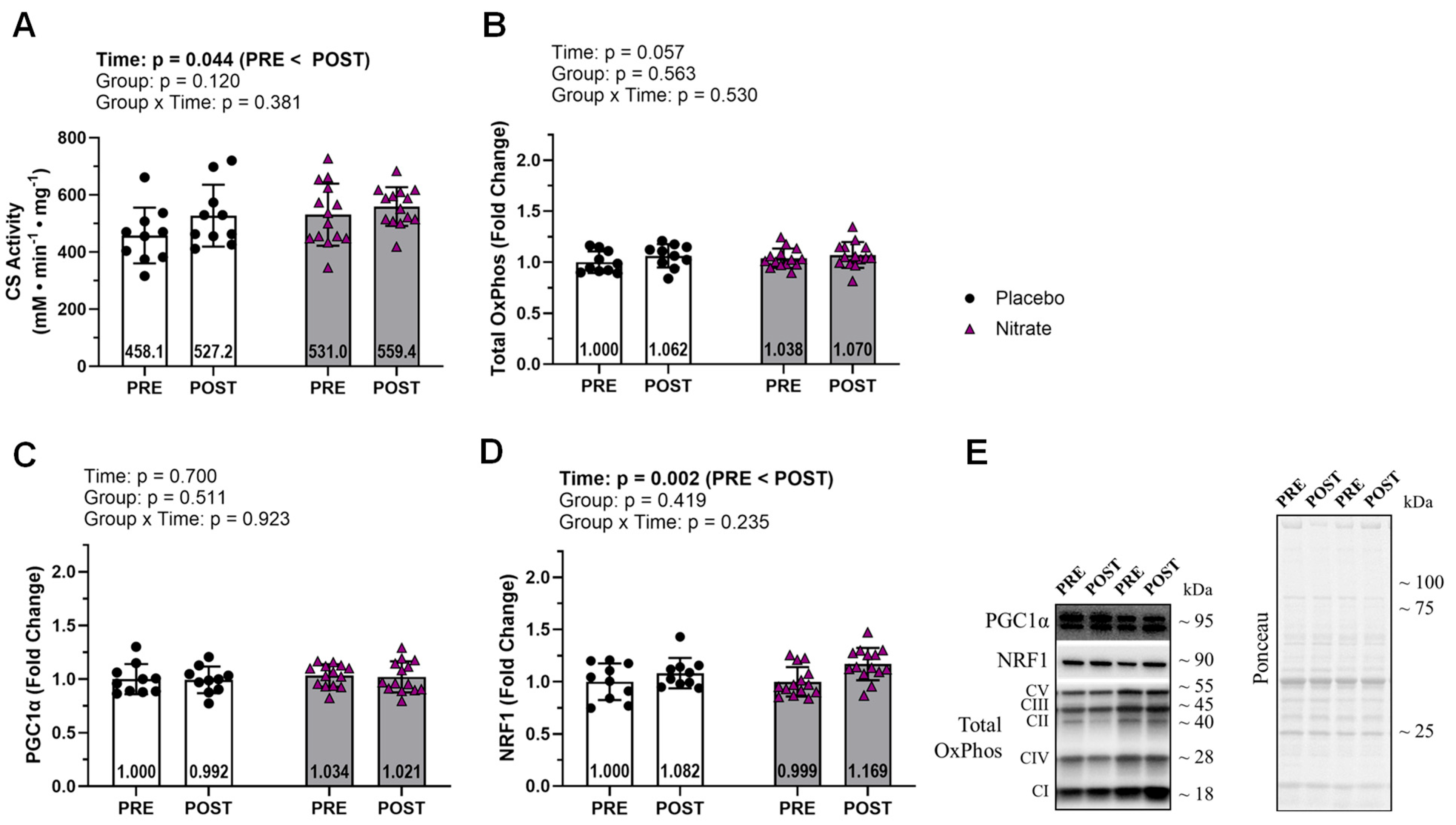

Mitochondrial Markers

Markers of mitochondrial content and biogenesis did not display any significant interactions (ƞ

p2 ≤ 0.063; p ≥ 0.235;

Figure 3). CS activity and NRF1 did, however, display significant main effects of time where POST was greater than PRE (ƞ

p2 ≥ 0.172; p ≤ 0.044;

Figure 3A&D).

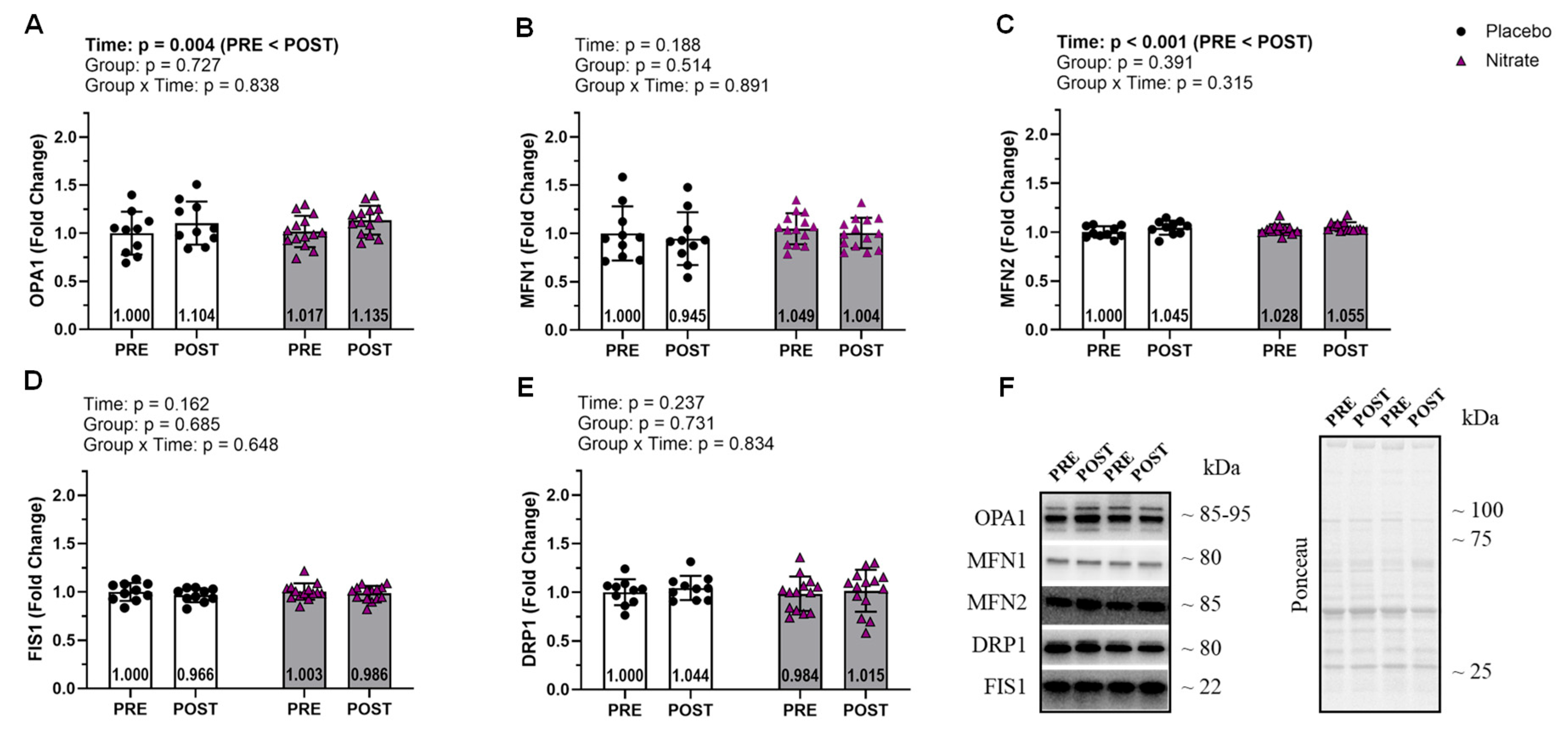

Proteins related to mitochondrial fusion and fission did not display significant interactions (ƞ

p2 ≤ 0.046; p ≥ 0.315;

Figure 4). However, OPA1 and MFN2 displayed significant main effects of time where POST was greater than PRE (ƞ

p2 ≥ 0.313; p ≤ 0.004;

Figure 4A&C).

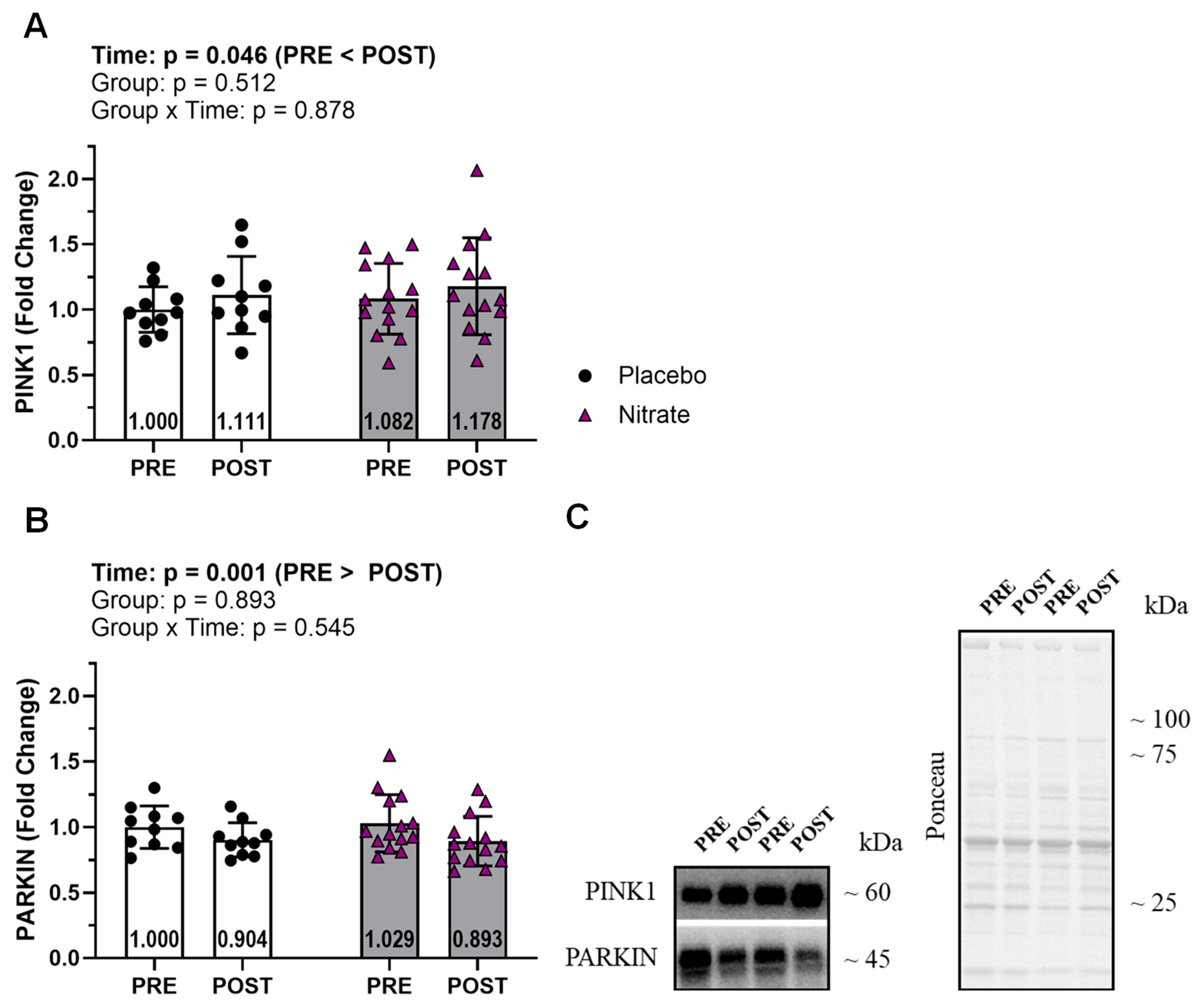

Mitophagy proteins PINK1 and PARKIN did not demonstrate significant interactions (ƞ

p2 ≤ 0.017; p ≥ 0.545;

Figure 5). However, both demonstrated significant main effects of time where PINK1 was higher at POST versus PRE and PARKIN was lower at POST versus PRE (ƞ

p2 ≥ 0.169; p ≤ 0.046).

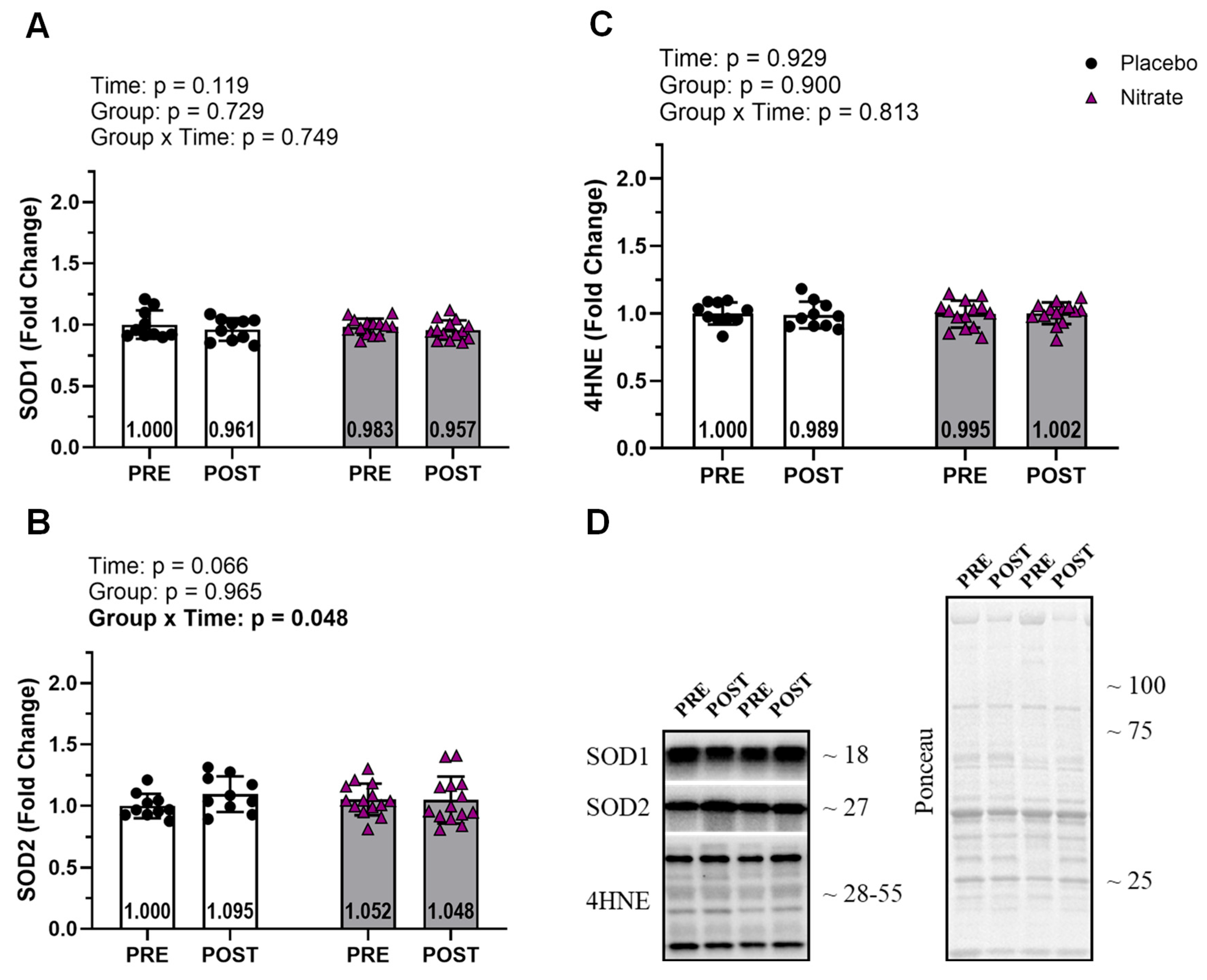

Markers of Redox Balance

Among markers of oxidative stress, only SOD2 demonstrated a significant interaction (ƞ

p2 = 0.166; p = 0.048;

Figure 6B). However, post hoc within- and between-group comparisons did not reach statistical significance (p ≥ 0.067). All other redox marker interactions were not significant (p ≥ 0.749;

Figure 6).

Discussion

In this study, nitrate supplementation did not alter markers of mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling or redox markers in older individuals over a 12-week resistance training period. Moreover, supplementation did not alter measures of knee extensor strength-endurance, power, or fatiguability. However, our results do support previous findings from our laboratory and others that resistance training stimulates changes in various markers of mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial remodeling, antioxidant production, and oxidative stress in older adults (Mesquita et al., 2020; Parise, Brose, et al., 2005; Parise, Phillips, et al., 2005; Parry et al., 2020). An expanded discussion of these results is presented in the following paragraphs.

Our hypothesis that nitrate supplementation would enhance mitochondrial adaptations with resistance training is based on previous findings that indicate nitric oxide stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis through AMPK and cGMP pathways (Lira et al., 2010; Nisoli & Carruba, 2006). We speculated that increases in mitochondrial biogenesis markers would be accompanied by increases in fission, fusion and mitophagy markers involved in quality control of the mitochondria. However, we observed only marginal increases in a marker of mitochondrial content (CS activity) and NRF1 protein levels in response to resistance training that was not enhanced with nitrate supplementation. There are a few possible reasons why we were unable to confirm our original hypotheses. First, it is possible that the enhanced stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis via dietary nitrates was masked by the training stimulus. In this regard, several studies indicate that mitochondrial biogenesis occurs in previously untrained older adults during periods of RT (Frank et al., 2016; Mesquita et al., 2020; Ogborn et al., 2015; Ruple, et al., 2021). RT is also known to stimulate [Akt and] mTOR signaling, which inhibits AMPK (Frank et al., 2016). Given that NO stimulates AMPK signaling, it is possible that training-induced increases in mTOR signaling interfered with NO-AMPK-mediated increases in mitochondrial biogenesis (Lira et al., 2010). The metabolic status of skeletal muscle may also influence the efficacy of NO-mediated stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis pathways. For example, Wadley and colleagues investigated the effects of NO in acute and chronic endurance exercise on mitochondrial biogenesis pathways in mice (Wadley et al., 2007). These authors utilized nitric oxide synthase knockout mouse models and assessed mRNA and protein levels of several genes involved in mitochondrial pathways (PGC1a, NRF2α, AMPK, COX IV). Interestingly, the authors reported that NO-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis occurs in skeletal muscle in the basal state, but that endurance training has no additive effect. Thus, these rodent data resonate with our current findings in that NO-mediated mitochondrial effects may be washed out with an exercise training stimulus.

Contrary to limited in vitro data indicating a role for NO in stimulating mitochondrial remodeling, we observed no effects of nitrate supplementation in enhancing these outcomes (He et al., 2018). However, we did observe training effects with increased levels of the mitochondrial fusion proteins OPA1 and MFN2, and no change in mitochondrial fission markers (DRP1 and FIS1). These results are consistent with observations that RT alters markers of mitochondrial fusion, but has little effect on markers of mitochondrial fission (Kitaoka et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2023; Mesquita et al., 2020). Although enhanced fusion and diminished fission may produce elongated mitochondria with a reduced functional capacity, these divergent dynamics events may also act to conserve mitochondrial content in older skeletal muscle (Marzetti et al., 2013). Fission and fusion events are closely linked to mitophagy, which is the degradation of sections of dysfunctional mitochondria. An increase in mitochondrial fission, which segments damaged portions of the mitochondria, is followed by an increase in mitophagy where these defective portions are eliminated (Nicholls & Ferguson, 2013). Indeed, we also observed an increase in PINK1 and a decrease in Parkin protein levels; both of which are involved in mitophagy (Nicholls & Ferguson, 2013). Our extensive interrogation of muscle mitochondrial markers in older adults suggests that: i) RT modestly increases mitochondrial content, ii) this increase is likely related to an interplay between increased biogenesis and dynamics, and iii) dietary nitrate supplementation does not alter this response.

We also hypothesized that dietary nitrate supplementation would increase antioxidant production and decrease oxidative stress compared to the placebo group. It has previously been reported that NO is able to activate antioxidant pathways through an indirect role in redox signaling (Mason et al., 2016). Due to its interactions with the electron transport chain, NO can augment ROS produced within the mitochondria (Moncada & Erusalimsky, 2002). ROS, in turn, stimulates antioxidant production pathways via activation of AMPK, MAPK, and NF-κB (Irrcher et al., 2009; Mason et al., 2016). NO has also been shown to affect redox state by acting as an antioxidant itself and neutralizing ROS (Wink et al., 1999, 2001). However, our results revealed a non-meaningful interaction effect of SOD2 and no significant interaction with our oxidative stress outcome (4HNE). Further post hoc analysis revealed an increase in SOD2 from PRE to POST in the placebo group and no significant change within the nitrate group. Taken together, these results indicate that dietary nitrate supplementation likely has no meaningful effect on skeletal muscle redox outcomes during RT.

Lastly, we hypothesized that nitrate supplementation would improve leg extensor performance outcomes. Though a limited number of studies have investigated the effect of nitrate supplementation on resistance exercise performance, initial findings have demonstrated an increase in repetitions to failure (Garnacho-Castaño et al., 2022; Ranchal-Sanchez et al., 2020; Tan, Pennell, et al., 2023). However, the overall results of this study showed no effect of chronic nitrate supplementation on measures of leg extensor strength, power, strength-endurance, or fatiguability. Although our findings are difficult to reconcile with prior studies, the observed effects are likely due to the age of participants and/or supplement timing and dosage. As previously reported by Wiley and colleagues, increased dosage of nitrate supplementation corresponds to increases in plasma nitrate and nitrite concentration (Wylie et al., 2013). Specifically, these authors reported that larger doses (140 mL and 280 mL containing 8.4 mmol and 16.8 mmol nitrate respectively) correlate with greater plasma nitrate and nitrite concentrations and improved exercise performance (i.e., time to task failure and end-exercise VO2). It is also notable that the timing of nitrate consumption (e.g., 1-2 hours prior to exercise) likely influences outcomes, and our participants discontinued supplementation 24 hours prior to post-testing (Mueller et al., 2024). However, it is notable that Carter et al. recently reported that 7 weeks of nitrate supplementation (followed by a one-week discontinuation period) increases in maximal knee extensor power in postmenopausal women who engaged in 8 weeks of circuit training (Carter et al., 2024). Thus, more research is needed to determine how supplement timing, dosage, and age of participants affects these outcomes.

Limitations

It is important to note key limitations of this study. One limitation is that nitrate dosage was not normalized to body weight. However, several studies have shown 140 mL of beet root juice is effective in improving exercise performance (Mueller et al., 2024). Notwithstanding, there is the potential existence of “non-responders” to nitrate supplementation (Wylie et al., 2013). In a study from Wilkerson and colleagues, “non-responders” to a lower (4.2 mmol nitrate) nitrate dosage required a significant increase in dosage before an effect on exercise performance was observed (Wilkerson et al., 2012). Regarding functional measures of muscular performance, we were unable to detect acute effects of nitrate supplementation since POST testing occurred one day after the final dose of nitrate supplementation, and skeletal muscle nitrate stores have been shown to return to normal levels as soon as 24 hours after consumption (Wei et al., 2024). Finally, while our small sample size was likely underpowered to detect differences between groups, the calculated effect sizes provide evidence that nitrate supplementation likely did not have meaningful effects on the assayed outcomes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results indicate that chronic nitrate supplementation during RT does not alter select markers of mitochondrial biogenesis or remodeling, redox balance, or leg extensor strength-endurance and fatiguability. However, our data provide further evidence that RT stimulates mitochondrial adaptations in older adults. Future studies are needed to further illuminate potential dietary nitrate timing and dosage considerations in this population.

Funding

Participant compensation and supplement costs were covered by a research grant (VCOM REAP) awarded to D.T.B., M.C.M., and M.D.R. by the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine. M.C.M. was fully supported by an American Physiological Society Porter fellowship. D.L. was fully supported by a Presidential Graduate Research Fellowship funded by Auburn University’s President’s office, the College of Education, and School of Kinesiology. Assay costs were provided through discretionary laboratory funds of A.N.K.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants who volunteered and participated in the study as well as other laboratory members who assisted with aspects of data collection unrelated to the current aims. Raw data related to the current study outcomes will be provided upon reasonable request by emailing the corresponding authors (mdr0024@auburn.edu and ank0012@auburn.edu).

Conflicts of Interest

All co-authors have no apparent conflicts of interest in relation to these data.

References

- Carter, S. J.; Blechschmid, T. H.; Baranauskas, M. N.; Long, E. B.; Gruber, A. H.; Raglin, J. S.; Lim, K.; Coggan, A. R. Preworkout dietary nitrate magnifies training-induced benefits to physical function in late postmenopausal women: A randomized pilot study. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2024, 327(6), R534–R542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Chen, L.; Cheng, S.; Li, F.; Lau, W. B.; Wang, L. F.; Liu, J. H. Aging aggravates nitrate-mediated ROS/RNS changes. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2014, 2014, 376515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, P.; Andersson, E.; Pontén, M.; Ekblom, B.; Ekblom, M.; Sahlin, K. Strength training improves muscle aerobic capacity and glucose tolerance in elderly. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2016, 26(7), 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, R.; Hawley, J. A.; Handschin, C. The molecular athlete: Exercise physiology from mechanisms to medals. Physiological Reviews 2023, 103(3), 1693–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnacho-Castaño, M. V.; Sánchez-Nuño, S.; Molina-Raya, L.; Carbonell, T.; Maté-Muñoz, J. L.; Pleguezuelos-Cobo, E.; Serra-Payá, N. Circulating nitrate-nitrite reduces oxygen uptake for improving resistance exercise performance after rest time in well-trained CrossFit athletes. Scientific Reports 2022, 12(1), 9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Ye, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, W.; Qian, X.; Yang, Y. Super-Resolution Monitoring of Mitochondrial Dynamics upon Time-Gated Photo-Triggered Release of Nitric Oxide. Analytical Chemistry 2018, 90(3), 2164–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoon, M. W.; Johnson, N. A.; Chapman, P. G.; Burke, L. M. The effect of nitrate supplementation on exercise performance in healthy individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2013, 23(5), 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrcher, I.; Ljubicic, V.; Hood, D. A. Interactions between ROS and AMP kinase activity in the regulation of PGC-1alpha transcription in skeletal muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology 2009, 296(1), C116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A. M. Dietary nitrate supplementation and exercise performance. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2014, 44 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A. M.; Vanhatalo, A.; Seals, D. R.; Rossman, M. J.; Piknova, B.; Jonvik, K. L. Dietary Nitrate and Nitric Oxide Metabolism: Mouth, Circulation, Skeletal Muscle, and Exercise Performance. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 2021, 53(2), 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedlian, V. R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Bolt, L.; Tudor, C.; Shen, Z.; Fasouli, E. S.; Prigmore, E.; Kleshchevnikov, V.; Pett, J. P.; Li, T.; Lawrence, J. E. G.; Perera, S.; Prete, M.; Huang, N.; Guo, Q.; Zeng, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H. Human skeletal muscle aging atlas. Nature Aging 2024, 4(5), 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kephart, W. C.; Mobley, C. B.; Fox, C. D.; Pascoe, D. D.; Sefton, J. M.; Wilson, T. J.; Goodlett, M. D.; Kavazis, A. N.; Roberts, M. D.; Martin, J. S. A single bout of whole-leg, peristaltic pulse external pneumatic compression upregulates PGC-1α mRNA and endothelial nitric oxide sythase protein in human skeletal muscle tissue. Experimental Physiology 2015, 100(7), 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaoka, Y.; Ogasawara, R.; Tamura, Y.; Fujita, S.; Hatta, H. Effect of electrical stimulation-induced resistance exercise on mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins in rat skeletal muscle. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism=Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et Metabolisme 2015, 40(11), 1137–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, F. J.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J. O.; Ekblom, B. Effects of dietary nitrate on oxygen cost during exercise. Acta Physiologica (Oxford, England) 2007, 191(1), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, S.; Nielsen, J.; Hansen, C. N.; Nielsen, L. B.; Wibrand, F.; Stride, N.; Schroder, H. D.; Boushel, R.; Helge, J. W.; Dela, F.; Hey-Mogensen, M. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. The Journal of Physiology 2012, 590(14), 3349–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, V. A.; Brown, D. L.; Lira, A. K.; Kavazis, A. N.; Soltow, Q. A.; Zeanah, E. H.; Criswell, D. S. Nitric oxide and AMPK cooperatively regulate PGC-1 in skeletal muscle cells. The Journal of Physiology 2010, 588 Pt 18, 3551–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, L.; Atochin, D. N.; Fattakhov, N.; Vasilenko, M.; Zatolokin, P.; Kirienkova, E. Nitric oxide and mitochondria in metabolic syndrome. Frontiers in Physiology 2015, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R. N.; McKendry, J.; Smeuninx, B.; Seabright, A. P.; Morgan, P. T.; Greig, C.; Breen, L. Acute resistance exercise training does not augment mitochondrial remodelling in master athletes or untrained older adults. Frontiers in Physiology 2023, 13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.1097988. [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Calvani, R.; Cesari, M.; Buford, T. W.; Lorenzi, M.; Behnke, B. J.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: From signaling pathways to clinical trials. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2013, 45(10), 2288–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S. A.; Morrison, D.; McConell, G. K.; Wadley, G. D. Muscle redox signalling pathways in exercise. Role of antioxidants. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2016, 98, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.; Mueller, B.; Tiede, D.; Anglin, D.; Jr, G. K.; Plotkin, D.; Mattingly, M.; Kontos, N.; Michel, J. M.; Agyin-Birikorang, A.; Harrison, K.; Peoples, B.; Roper, J.; Lewis, D.; Chirico, M. K.; Kannan, H.; Goodlett, M.; Gladden, L. B.; Fruge, A.; Roberts, M. Effects of 12-Week Dietary Nitrate Supplementation with Resistance Training on Skeletal Muscle and Vascular Outcomes and in Older Adults (2025072250). Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, N. F.; Leveritt, M. D.; Pavey, T. G. The Effect of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Endurance Exercise Performance in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2017, 47(4), 735–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, P. H. C.; Godwin, J. S.; Ruple, B. A.; Sexton, C. L.; McIntosh, M. C.; Mueller, B. J.; Osburn, S. C.; Mobley, C. B.; Libardi, C. A.; Young, K. C.; Gladden, L. B.; Roberts, M. D.; Kavazis, A. N. Resistance training diminishes mitochondrial adaptations to subsequent endurance training in healthy untrained men. The Journal of Physiology 2023, 601(17), 3825–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, P. H. C.; Lamb, D. A.; Parry, H. A.; Moore, J. H.; Smith, M. A.; Vann, C. G.; Osburn, S. C.; Fox, C. D.; Ruple, B. A.; Huggins, K. W.; Fruge, A. D.; Young, K. C.; Kavazis, A. N.; Roberts, M. D. Acute and chronic effects of resistance training on skeletal muscle markers of mitochondrial remodeling in older adults. Physiological Reports 2020, 8(15), e14526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncada, S.; Erusalimsky, J. D. Does nitric oxide modulate mitochondrial energy generation and apoptosis? Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 2002, 3(3), 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosher, S. L.; Sparks, S. A.; Williams, E. L.; Bentley, D. J.; Mc Naughton, L. R. Ingestion of a Nitric Oxide Enhancing Supplement Improves Resistance Exercise Performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2016, 30(12), 3520–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, B. J.; Roberts, M. D.; Mobley, C. B.; Judd, R. L.; Kavazis, A. N. Nitric oxide in exercise physiology: Past and present perspectives. Frontiers in Physiology 2024, 15, 1504978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseem, K. M. The role of nitric oxide in cardiovascular diseases. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2005, 26(1–2), 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, D.; Ferguson, S. Bioenergetics, 4th ed.; Academic Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nisoli, E.; Carruba, M. O. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial biogenesis. Journal of Cell Science 2006, 119 Pt 14, 2855–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogborn, D. I.; McKay, B. R.; Crane, J. D.; Safdar, A.; Akhtar, M.; Parise, G.; Tarnopolsky, M. A. Effects of age and unaccustomed resistance exercise on mitochondrial transcript and protein abundance in skeletal muscle of men. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2015, 308(8), R734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, G.; Brose, A. N.; Tarnopolsky, M. A. Resistance exercise training decreases oxidative damage to DNA and increases cytochrome oxidase activity in older adults. Experimental Gerontology 2005, 40(3), 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parise, G.; Phillips, S. M.; Kaczor, J. J.; Tarnopolsky, M. A. Antioxidant enzyme activity is up-regulated after unilateral resistance exercise training in older adults. Free Radical Biology & Medicine 2005, 39(2), 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, H. A.; Roberts, M. D.; Kavazis, A. N. Human Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Adaptations Following Resistance Exercise Training. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2020, 41(6), 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchal-Sanchez, A.; Diaz-Bernier, V. M.; De La Florida-Villagran, C. A.; Llorente-Cantarero, F. J.; Campos-Perez, J.; Jurado-Castro, J. M. Acute Effects of Beetroot Juice Supplements on Resistance Training: A Randomized Double-Blind Crossover. Nutrients 2020, 12(7), 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M. D.; McCarthy, J. J.; Hornberger, T. A.; Phillips, S. M.; Mackey, A. L.; Nader, G. A.; Boppart, M. D.; Kavazis, A. N.; Reidy, P. T.; Ogasawara, R.; Libardi, C. A.; Ugrinowitsch, C.; Booth, F. W.; Esser, K. A. Mechanisms of mechanical overload-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy: Current understanding and future directions. Physiological Reviews 2023, 103(4), 2679–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruple, B. A.; Godwin, J. S.; Mesquita, P. H. C.; Osburn, S. C.; Sexton, C. L.; Smith, M. A.; Ogletree, J. C.; Goodlett, M. D.; Edison, J. L.; Ferrando, A. A.; Fruge, A. D.; Kavazis, A. N.; Young, K. C.; Roberts, M. D. Myofibril and Mitochondrial Area Changes in Type I and II Fibers Following 10 Weeks of Resistance Training in Previously Untrained Men. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2021.728683. [CrossRef]

- Ruple, B. A.; Godwin, J. S.; Mesquita, P. H. C.; Osburn, S. C.; Vann, C. G.; Lamb, D. A.; Sexton, C. L.; Candow, D. G.; Forbes, S. C.; Frugé, A. D.; Kavazis, A. N.; Young, K. C.; Seaborne, R. A.; Sharples, A. P.; Roberts, M. D. Resistance training rejuvenates the mitochondrial methylome in aged human skeletal muscle. The FASEB Journal 2021, 35(9), e21864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruple, B. A.; Mesquita, P. H. C.; Godwin, J. S.; Sexton, C. L.; Osburn, S. C.; McIntosh, M. C.; Kavazis, A. N.; Libardi, C. A.; Young, K. C.; Roberts, M. D. Changes in vastus lateralis fibre cross-sectional area, pennation angle and fascicle length do not predict changes in muscle cross-sectional area. Experimental Physiology 2022, 107(11), 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruple, B. A.; Smith, M. A.; Osburn, S. C.; Sexton, C. L.; Godwin, J. S.; Edison, J. L.; Poole, C. N.; Stock, M. S.; Fruge, A. D.; Young, K. C.; Roberts, M. D. Comparisons between skeletal muscle imaging techniques and histology in tracking midthigh hypertrophic adaptations following 10 wk of resistance training. Journal of Applied Physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985) 2022, 133(2), 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S. H. Nitric oxide and neurons. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 1992, 2(3), 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soodaeva, S.; Klimanov, I.; Kubysheva, N.; Popova, N.; Batyrshin, I. The State of the Nitric Oxide Cycle in Respiratory Tract Diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 2020, 4859260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.; Baranauskas, M. N.; Karl, S. T.; Ortiz de Zevallos, J.; Shei, R.-J.; Paris, H. L.; Wiggins, C. C.; Bailey, S. J. Effects of dietary nitrate supplementation on muscular power output: Influence of supplementation strategy and population. In Biology and Chemistry; Nitric Oxide, 2023; Volume 136–137, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Pennell, A.; Karl, S. T.; Cass, J. K.; Go, K.; Clifford, T.; Bailey, S. J.; Storm Perkins, C. Effects of Dietary Nitrate Supplementation on Back Squat and Bench Press Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15(11), 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadley, G. D.; Choate, J.; McConell, G. K. NOS isoform-specific regulation of basal but not exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse skeletal muscle. The Journal of Physiology 2007, 585 Pt 1, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Vanhatalo, A.; Black, M. I.; Blackwell, J. R.; Rajaram, R.; Kadach, S.; Jones, A. M. Relationships between nitric oxide biomarkers and physiological outcomes following dietary nitrate supplementation. In Biology and Chemistry; Nitric Oxide, 2024; Volume 148, pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, D. P.; Hayward, G. M.; Bailey, S. J.; Vanhatalo, A.; Blackwell, J. R.; Jones, A. M. Influence of acute dietary nitrate supplementation on 50 mile time trial performance in well-trained cyclists. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2012, 112(12), 4127–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, D. A.; Miranda, K. M.; Espey, M. G.; Pluta, R. M.; Hewett, S. J.; Colton, C.; Vitek, M.; Feelisch, M.; Grisham, M. B. Mechanisms of the antioxidant effects of nitric oxide. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2001, 3(2), 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, D. A.; Vodovotz, Y.; Grisham, M. B.; DeGraff, W.; Cook, J. C.; Pacelli, R.; Krishna, M.; Mitchell, J. B. Antioxidant effects of nitric oxide. Methods in Enzymology 1999, 301, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L. J.; Kelly, J.; Bailey, S. J.; Blackwell, J. R.; Skiba, P. F.; Winyard, P. G.; Jeukendrup, A. E.; Vanhatalo, A.; Jones, A. M. Beetroot juice and exercise: Pharmacodynamic and dose-response relationships. In Journal of Applied Physiology; Bethesda, Md., 2013; Volume 115, 3, pp. 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zourdos, M. C.; Klemp, A.; Dolan, C.; Quiles, J. M.; Schau, K. A.; Jo, E.; Helms, E.; Esgro, B.; Duncan, S.; Garcia Merino, S.; Blanco, R. Novel Resistance Training-Specific Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale Measuring Repetitions in Reserve. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2016, 30(1), 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Study Design. Twenty-seven older participants (13 M,14 F) were block randomized to either the Placebo (nitrate-depleted beet root juice) or Nitrate (nitrate-rich beet root juice) group and completed 12 weeks of total body resistance training (RT). All participants consumed 140 mL per day of their respective supplement, with the Nitrate supplement providing ~13 mmol of dietary nitrates. PRE and POST testing measures were completed 3-6 days before and ~3 days after the intervention and supplementation was discontinued 24 hours prior to POST testing.

Figure 1.

Study Design. Twenty-seven older participants (13 M,14 F) were block randomized to either the Placebo (nitrate-depleted beet root juice) or Nitrate (nitrate-rich beet root juice) group and completed 12 weeks of total body resistance training (RT). All participants consumed 140 mL per day of their respective supplement, with the Nitrate supplement providing ~13 mmol of dietary nitrates. PRE and POST testing measures were completed 3-6 days before and ~3 days after the intervention and supplementation was discontinued 24 hours prior to POST testing.

Figure 2.

Muscular Strength-endurance, Power, and Fatigue. 30 LE Work Fatigue included 30 isokinetic left leg extensor repetitions at 180 degrees per second (A). 30 LE Work in Last Third indicates work performed during the last 10 repetitions of the test (B), 30 LE Total Work indicates work performed during all 30 repetitions (C). 6 LE Peak Torque is the maximal strength/torque during 6 repetitions at 90 degrees per second (D). 30 LE Peak Torque is the maximal strength/torque during 30 repetitions at 180 degrees per second (E). 30 LE Average Peak Torque is the mean value during 30 repetitions at 180 degrees per second (F). 30 LE Average Power is the mean value during 30 repetitions at 180 degrees per second (G). All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 2.

Muscular Strength-endurance, Power, and Fatigue. 30 LE Work Fatigue included 30 isokinetic left leg extensor repetitions at 180 degrees per second (A). 30 LE Work in Last Third indicates work performed during the last 10 repetitions of the test (B), 30 LE Total Work indicates work performed during all 30 repetitions (C). 6 LE Peak Torque is the maximal strength/torque during 6 repetitions at 90 degrees per second (D). 30 LE Peak Torque is the maximal strength/torque during 30 repetitions at 180 degrees per second (E). 30 LE Average Peak Torque is the mean value during 30 repetitions at 180 degrees per second (F). 30 LE Average Power is the mean value during 30 repetitions at 180 degrees per second (G). All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial Content and Biogenesis. Data for mitochondrial content markers including Citrate Synthase Activity (A) and total OxPhos (B). Mitochondrial biogenesis markers include PGC1α and NRF1 (C and D). Representative western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel E. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 3.

Mitochondrial Content and Biogenesis. Data for mitochondrial content markers including Citrate Synthase Activity (A) and total OxPhos (B). Mitochondrial biogenesis markers include PGC1α and NRF1 (C and D). Representative western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel E. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial Fusion and Fission. Data for mitochondrial fusion markers including OPA1, MFN1, and MFN2 (A-C). Data for mitochondrial fission markers FIS1 and DRP1 (D and E). Representative western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel F. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial Fusion and Fission. Data for mitochondrial fusion markers including OPA1, MFN1, and MFN2 (A-C). Data for mitochondrial fission markers FIS1 and DRP1 (D and E). Representative western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel F. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 5.

Mitophagy. Assayed mitophagy markers included PINK and PARKIN (A and B). Representative western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel C. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 5.

Mitophagy. Assayed mitophagy markers included PINK and PARKIN (A and B). Representative western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel C. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 6.

Redox balance. Endogenous antioxidants SOD1 and SOD2 (A and B), and an oxidative damage marker 4HNE (C) are presented. Representative of the western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel D. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Figure 6.

Redox balance. Endogenous antioxidants SOD1 and SOD2 (A and B), and an oxidative damage marker 4HNE (C) are presented. Representative of the western blot for each protein and representative ponceau are presented in panel D. All bar graph data are presented as means ± standard deviation values, with individual respondent values superimposed and mean values provided at the bottom of bars. P-values for supplementation group (group), training effects (time), and interactions are provided within each graph.

Table 1.

Resistance Training Program.

Table 1.

Resistance Training Program.

| Exercises |

Week |

Sets |

Repetitions |

RIR |

Upper body

Chest press

Lat pulldown

Lower body

Hex-bar deadlift

Leg press

Leg extension

Hamstring curl |

1-4

5-8

9-12 |

3

3

3 |

15

12

10 |

0-2

0-2

0-2 |

Table 2.

Western Blot Antibodies.

Table 2.

Western Blot Antibodies.

| Target |

Acronym |

Company |

Catalog # |

RRID |

| Total OXPHOS |

- |

Abcam |

ab110411 |

RRID:AB_2756818 |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

PGC1α |

GeneTex |

GTX37356 |

RRID:AB_11175466 |

| Nuclear respiratory factor 1 |

NRF1 |

GeneTex |

GTX103179 |

RRID:AB_11168915 |

| Optic atrophy 1 |

OPA1 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

67589 |

RRID:AB_2799728 |

| Dynamin related protein 1 |

DRP1 |

Novus |

NB110– 55288SS |

RRID:AB_921147 |

| Mitofusin 1 |

MFN1 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

14739 |

RRID:AB_2744531 |

| Mitofusin 2 |

MFN2 |

BioVision |

3882– 100 |

RRID:AB_2142625 |

| PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

PINK1 |

Cell Signaling Technology |

6946 |

RRID:AB_11179069 |

| Parkin protein 2, E3 ubiquitin protein ligase |

PARKIN |

Cell Signaling Technology |

2132 |

RRID:AB_10693040 |

| Superoxide dismutase 1 |

SOD1 |

GeneTex |

GTX100554 |

RRID:AB_10618670 |

| Superoxide dismutase 2 |

SOD2 |

GeneTex |

GTX116093 |

RRID:AB_10624558 |

| 4-Hydroxynonenal |

4HNE |

Abcam |

ab46545 |

RRID:AB_722490 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG |

- |

GeneTex |

GTX213110-01 |

RRID:AB_10618573 |

| Anti-mouse IgG |

- |

Cell Signaling Technology |

7076 |

RRID:AB_330924 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).