Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

12 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Size

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Participants and Screenings

2.4. Experiments

2.4.1. Experiment 1

2.4.2. Experiment 2

2.5. Jelly Preparation

2.6. Biochemical Assays

2.7. Antioxidant Biomarker Assay

2.8. Inflammatory Cytokines Assay

2.9. Endurance Performance Test

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Participant Characteristics

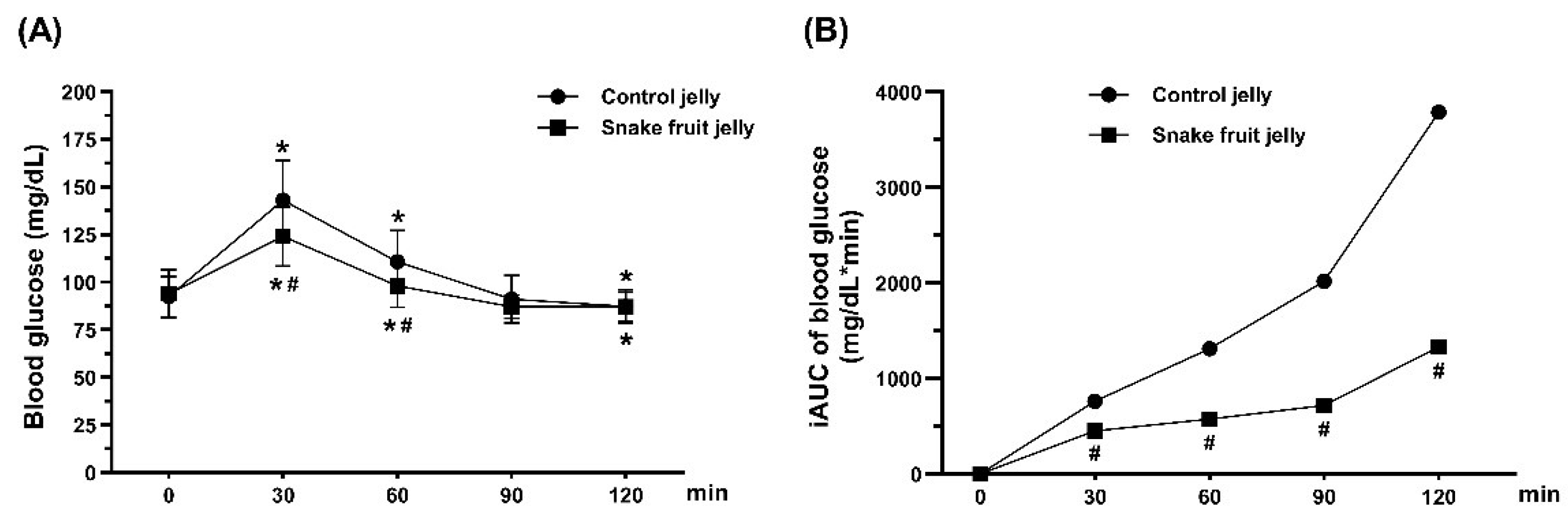

3.1.2. Blood Glucose and Incremental Area Under the Blood Glucose Curve

3.2. Experiment 2

3.2.1. Participant Characteristics

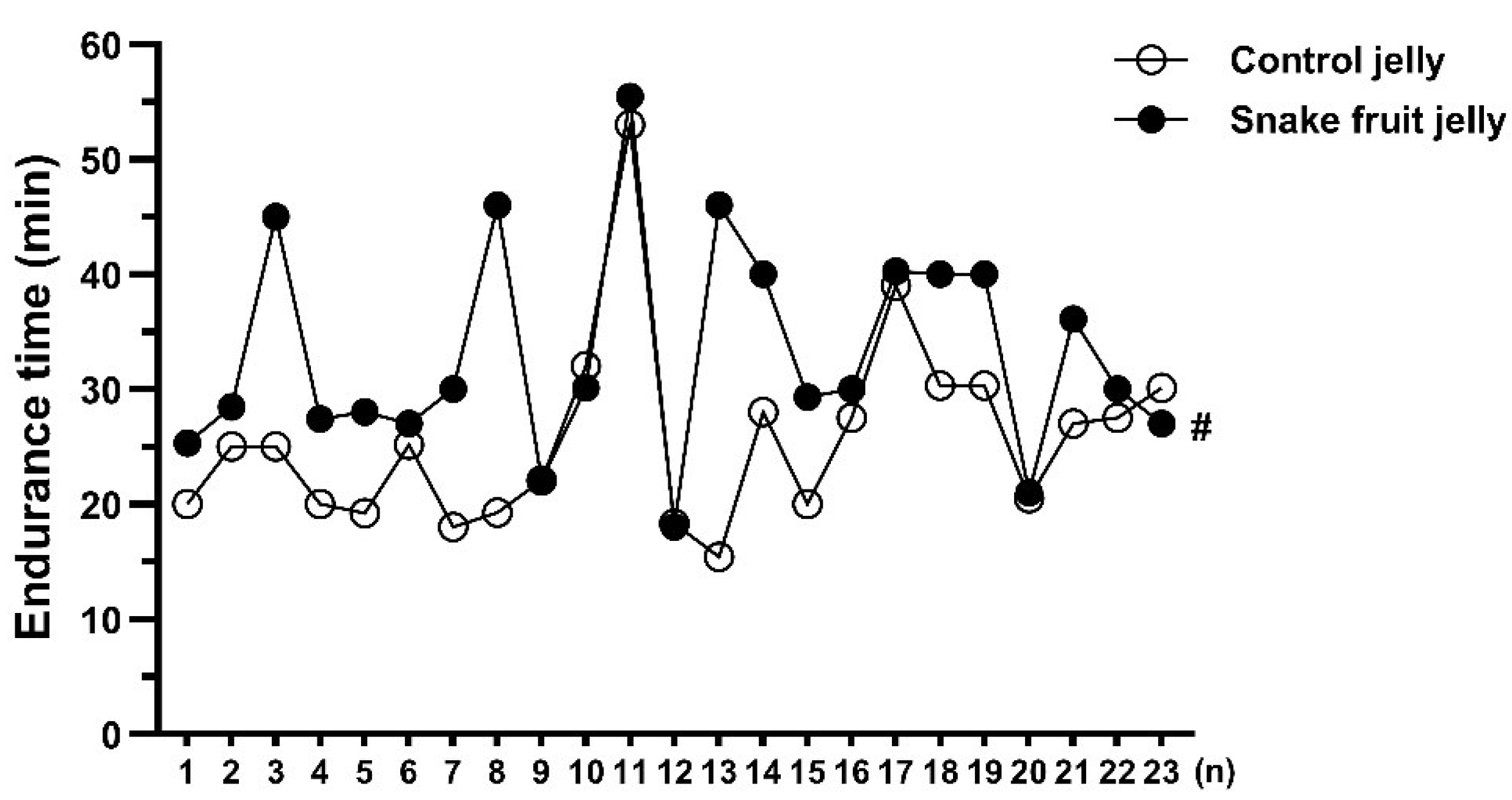

3.2.2. Endurance Performance

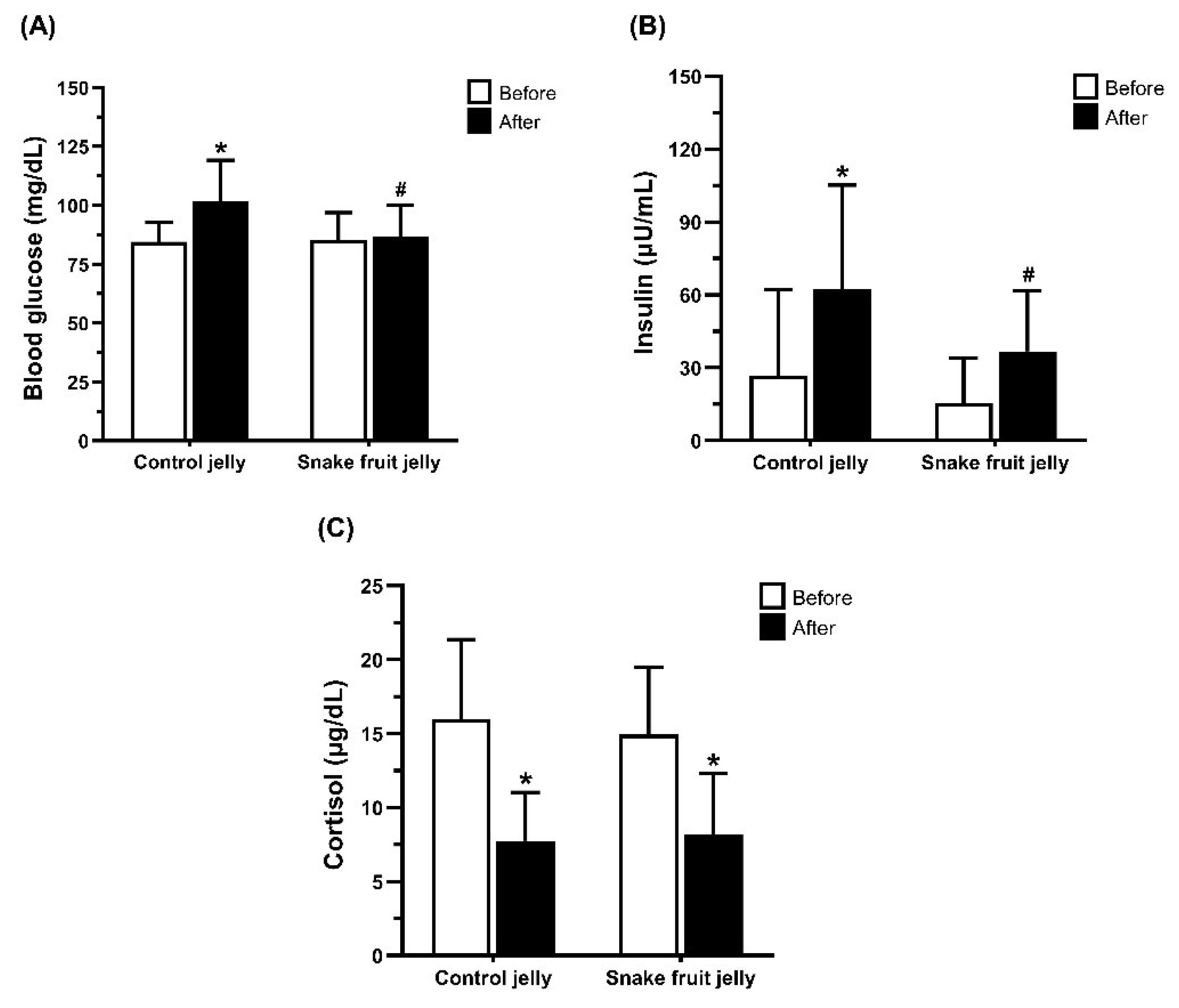

3.2.3. Blood Glucose, Insulin, and Cortisol

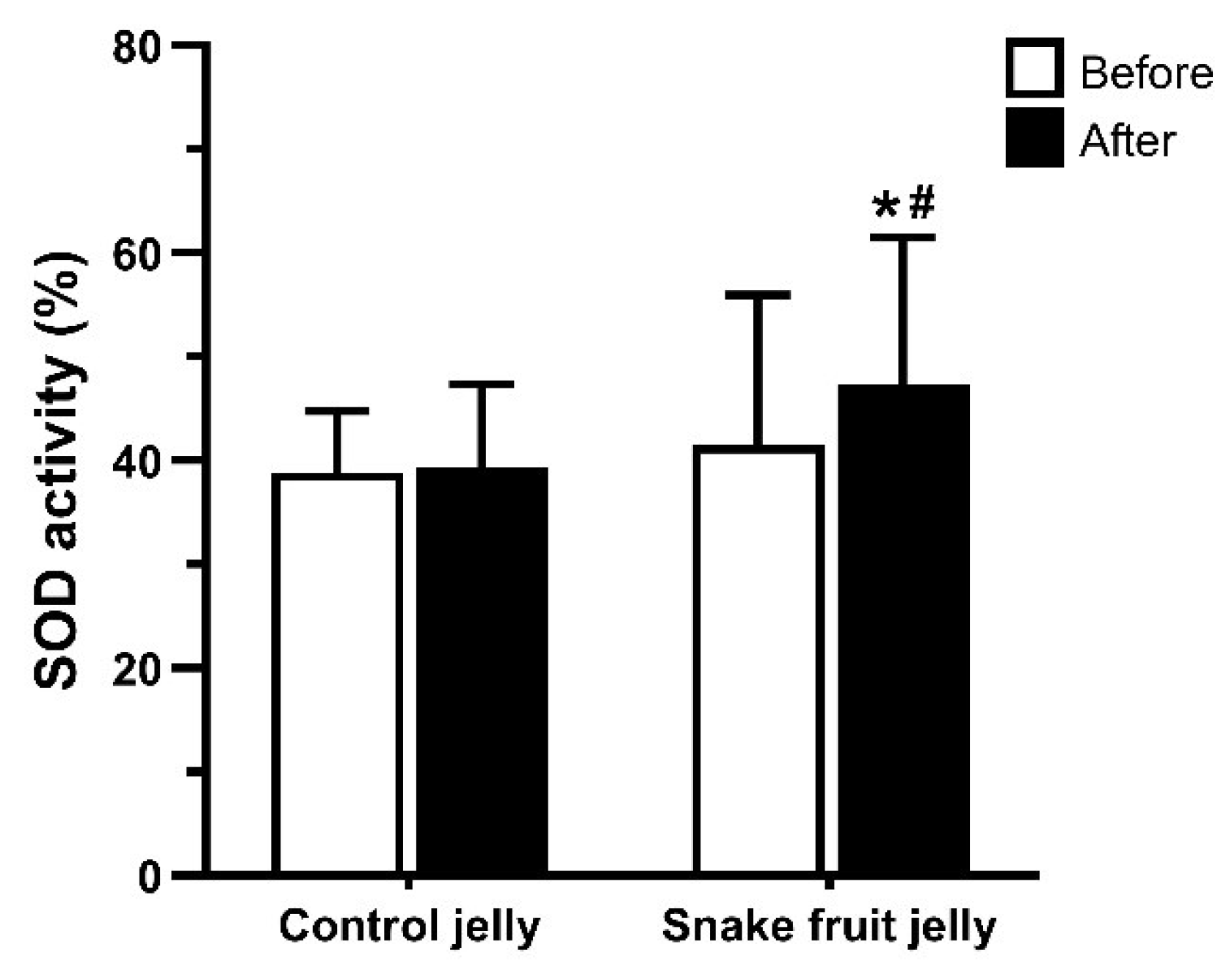

3.2.4. Antioxidant Biomarker

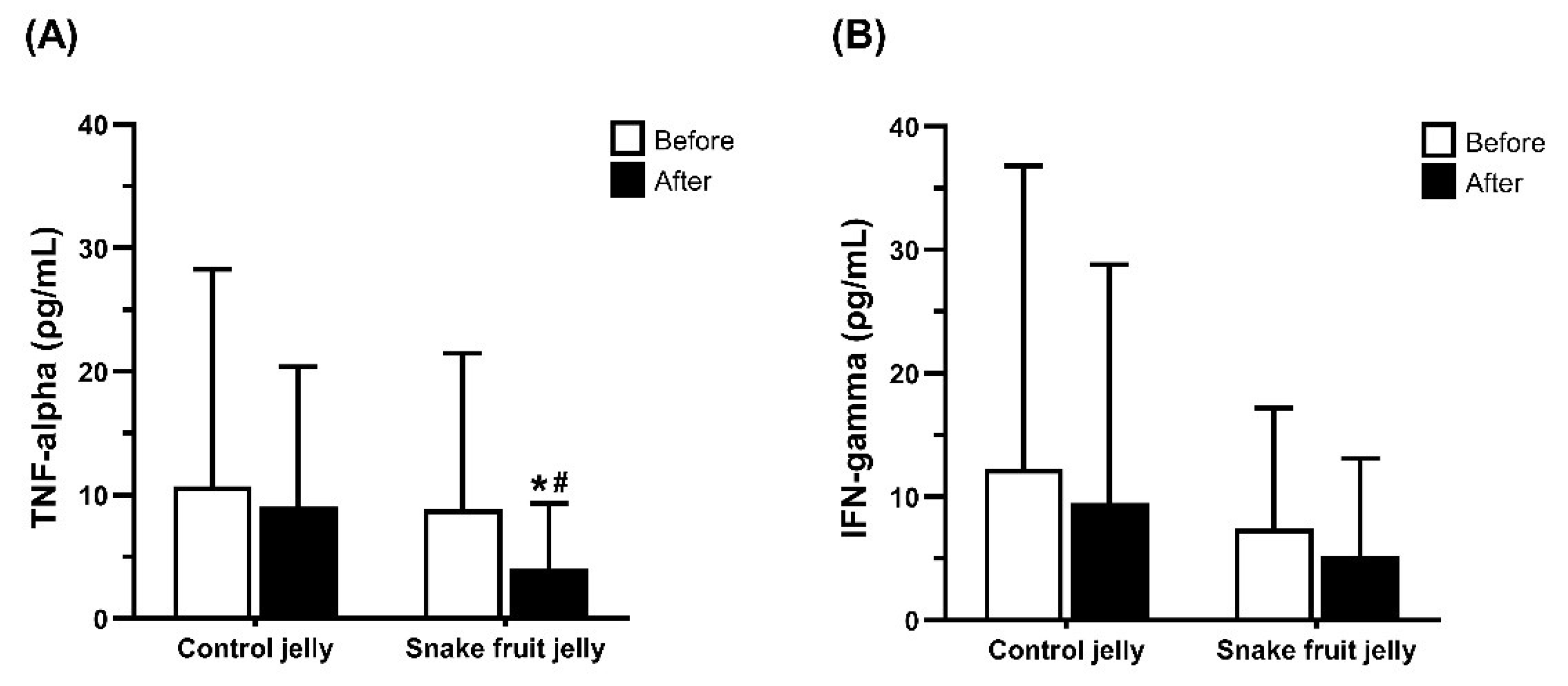

3.2.5. Inflammatory Cytokines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BM | Body mass |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| iAUC | Incremental area under the curve |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| PGC | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| VO2max | Maximal oxygen consumption |

| VO2peak | Peak oxygen consumption |

References

- Lauritzen, F.; Gjelstad, A. Trends in dietary supplement use among athletes selected for doping controls. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1143187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maughan, R.J.; Depiesse, F.; Geyer, H. The use of dietary supplements by athletes. J Sports Sci 2007, 25 Suppl 1, S103–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthe, I.; Maughan, R.J. Athletes and Supplements: Prevalence and Perspectives. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018, 28, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, M.R.; Izadi, A.; Kaviani, M. Antioxidants and Exercise Performance: With a Focus on Vitamin E and C Supplementation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlásná Čepková, P.; Jágr, M.; Janovská, D.; Dvořáček, V.; Kotrbová Kozak, A.; Viehmannová, I. Comprehensive Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Snake Fruit: Salak (Salacca zalacca). J Food Qual 2021, 2021, 6621811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Siddiqui, M.J.; Mat So’ad, S.; Murugesu, S.; Khatib, A.; Rahman, M. Antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry profile of salak (Salacca zalacca) fruit peel extracts. Pharmacogn Res 2018, 10, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.S.M.; Siddiqui, M.J.; Mediani, A.; Ismail, N.H.; Ahmed, Q.U.; So’ad, S.Z.M.; Saidi-Besbes, S. Salacca zalacca: A short review of the palm botany, pharmacological uses and phytochemistry. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2018, 11, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontowicz, H.; Leontowicz, M.; Drzewiecki, J.; Haruenkit, R.; Poovarodom, S.; Park, Y.-S.; Jung, S.-T.; Kang, S.-G.; Trakhtenberg, S.; Gorinstein, S. Bioactive properties of Snake fruit (Salacca edulis Reinw) and Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) and their influence on plasma lipid profile and antioxidant activity in rats fed cholesterol. Eur Food Res Technol 2006, 223, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, D.; Campbell, M., J. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Studies. In Design of Studies for Medical Research; 2005; pp. 78-108.

- Prasertsri, P.; Booranasuksakul, U.; Naravoratham, K.; Trongtosak, P. Acute Effects of Passion Fruit Juice Supplementation on Cardiac Autonomic Function and Blood Glucose in Healthy Subjects. Prev Nutr Food Sci 2019, 24, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, A.M.; Mullenbach, M.J.; Fountaine, C.J. Actual Versus Predicted Cardiovascular Demands in Submaximal Cycle Ergometer Testing. Int J Exerc Sci 2015, 8, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.B. Reactive Oxygen Species as Agents of Fatigue. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016, 48, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pļaviņa, L.; Edelmers, E. Oxidative Stress Modulation and Glutathione System Response During a 10-Day Multi-Stressor Field Training. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.A.; Trewin, A.J.; Parker, L.; Wadley, G.D. Antioxidant supplements and endurance exercise: Current evidence and mechanistic insights. Redox Biol 2020, 35, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braakhuis, A.J. Effect of vitamin C supplements on physical performance. Curr Sports Med Rep 2012, 11, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Effect of high-dose vitamin C and E supplementation on muscle recovery and training adaptation: a mini review. Phys Act Nutr 2023, 27, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Touyz, R.M.; Park, J.B.; Schiffrin, E.L. Antioxidant effects of vitamins C and E are associated with altered activation of vascular NADPH oxidase and superoxide dismutase in stroke-prone SHR. Hypertension 2001, 38, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, G.; Gleeson, M. Influence of acute vitamin C and/or carbohydrate ingestion on hormonal, cytokine, and immune responses to prolonged exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2005, 15, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, L.M.; Mitic, N.R.; Miric, D.; Bisevac, B.; Miric, M.; Popovic, B. Influence of vitamin C supplementation on oxidative stress and neutrophil inflammatory response in acute and regular exercise. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 295497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimcharoen, M.; Kittikunnathum, S.; Suknikorn, C.; Nak-On, W.; Yeethong, P.; Anthony, T.G.; Bunpo, P. Effects of ascorbic acid supplementation on oxidative stress markers in healthy women following a single bout of exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Wentz, L.M. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. J Sport Health Sci 2019, 8, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karshikoff, B.; Sundelin, T.; Lasselin, J. Role of Inflammation in Human Fatigue: Relevance of Multidimensional Assessments and Potential Neuronal Mechanisms. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicer, S.; Reiser, P.J.; Ching, S.; Quan, N. Induction of muscle weakness by local inflammation: an experimental animal model. Inflamm Res 2009, 58, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.J.; Qin, Z.; Wang, P.Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X. Muscle fatigue: general understanding and treatment. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49, e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhostin-Roohi, B.; Babaei, P.; Rahmani-Nia, F.; Bohlooli, S. Effect of vitamin C supplementation on lipid peroxidation, muscle damage and inflammation after 30-min exercise at 75% VO2max. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2008, 48, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Righi, N.C.; Schuch, F.B.; De Nardi, A.T.; Pippi, C.M.; de Almeida Righi, G.; Puntel, G.O.; da Silva, A.M.V.; Signori, L.U. Effects of vitamin C on oxidative stress, inflammation, muscle soreness, and strength following acute exercise: meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials. Eur J Nutr 2020, 59, 2827–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos de Lima, K.; Schuch, F.B.; Camponogara Righi, N.; Chagas, P.; Hemann Lamberti, M.; Puntel, G.O.; Vargas da Silva, A.M.; Ulisses Signori, L. Effects of the combination of vitamins C and E supplementation on oxidative stress, inflammation, muscle soreness, and muscle strength following acute physical exercise: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2023, 63, 7584–7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, E.; Koekkoek, W.A.C.; Grefte, S.; Witkamp, R.F.; van Zanten, A.R.H. Feeding mitochondria: Potential role of nutritional components to improve critical illness convalescence. Clin Nutr 2019, 38, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, G.; Ghiasvand, R.; Karimian, J.; Feizi, A.; Paknahad, Z.; Sharifirad, G.; Hajishafiei, M. Does quercetin and vitamin C improve exercise performance, muscle damage, and body composition in male athletes? J Res Med Sci 2012, 17, 328–331. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.C.; Sung, Y.C.; Davison, G.; Chen, C.Y.; Liao, Y.H. Short-Term High-Dose Vitamin C and E Supplementation Attenuates Muscle Damage and Inflammatory Responses to Repeated Taekwondo Competitions: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int J Med Sci 2018, 15, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillam, I.H.; Cunningham, R.B.; Telford, R.D. Antioxidant Supplementation Protects Elite Athlete Muscle Integrity During Submaximal Training. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2022, 17, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Bustamante-Sanchez, Á.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Martínez-Guardado, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Antioxidants and Sports Performance. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Yin, J.; Chen, J.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; Liu, G.; Yao, K.; Tan, B.; Yin, Y. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants: A Step towards Disease Treatment. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 8837893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Zhao, J.; Li, F.; Zhao, X.; Feng, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, J. Vitamin A regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and function through p38 MAPK-PGC-1α signaling pathway and alters the muscle fiber composition of sheep. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 2024, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oboh, G.; Agunloye, O.M.; Adefegha, S.A.; Akinyemi, A.J.; Ademiluyi, A.O. Caffeic and chlorogenic acids inhibit key enzymes linked to type 2 diabetes (in vitro): a comparative study. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 2015, 26, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkhaleq, L.A.; Assi, M.A.; Noor, M.H.M.; Abdullah, R.; Saad, M.Z.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Therapeutic uses of epicatechin in diabetes and cancer. Vet World 2017, 10, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Li, D.; Shi, R.; Wang, M. Proanthocyanidin B(2) attenuates postprandial blood glucose and its inhibitory effect on alpha-glucosidase: analysis by kinetics, fluorescence spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy and molecular docking. Food Funct 2018, 9, 4673–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni Iii, V.L.; Welland, D. Intake of 100% Fruit Juice Is Associated with Improved Diet Quality of Adults: NHANES 2013-2016 Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Rasmussen, B.; van Loon, L.J.C.; Salmon, J.; Wadley, G.D. Ascorbic acid supplementation improves postprandial glycaemic control and blood pressure in individuals with type 2 diabetes: Findings of a randomized cross-over trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019, 21, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashor, A.W.; Werner, A.D.; Lara, J.; Willis, N.D.; Mathers, J.C.; Siervo, M. Effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycaemic control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr 2017, 71, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Hosseini, F.; Namkhah, Z.; Mohammadi, S.; Salamat, S.; Nadery, M.; Yarmand, S.; Zamani, M.; Wong, A.; et al. The effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2023, 17, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afkhami-Ardekani, M.; Shojaoddiny-Ardekani, A. Effect of vitamin C on blood glucose, serum lipids & serum insulin in type 2 diabetes patients. Indian J Med Res 2007, 126, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J.H.; Gheewala, N.M.; O’Keefe, J.O. Dietary strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 51, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viña, J.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Lloret, A.; Marquez, R.; Miñana, J.B.; Pallardó, F.V.; Sastre, J. Free radicals in exhaustive physical exercise: mechanism of production, and protection by antioxidants. IUBMB Life 2000, 50, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, P.A.; DeRubertis, F.R.; Kagan, V.E.; Melhem, M.; Studer, R.K. Effects of supplementation with vitamin C or E on albuminuria, glomerular TGF-beta, and glomerular size in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997, 8, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, male–female) | 4:21 | - | - |

| Age (years) | 22.60 ± 3.33 | 19 | 35 |

| Height (cm) | 159.52 ± 7.12 | 148 | 174 |

| Body mass (kg) | 52.89 ± 8.68 | 40.80 | 72.10 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 20.64 ± 2.15 | 18.51 | 24.89 |

| Heart rate (/min) | 78.62 ± 12.52 | 56 | 97 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 103.02 ± 10.41 | 88 | 131 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 66.30 ± 7.99 | 54 | 85 |

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (n, male–female) | 2:21 | - | - |

| Age (years) | 21.57 ± 1.88 | 20 | 29 |

| Height (cm) | 159.52 ± 7.12 | 148 | 174 |

| Body mass (kg) | 53.26 ± 6.71 | 41 | 69 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 20.86 ± 1.52 | 17.60 | 23.60 |

| Heart rate (/min) | 100.83 ± 12.96 | 69 | 120 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 110.48 ± 9.75 | 90 | 126 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 68.57 ± 6.97 | 59 | 81 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 98.70 ± 1.02 | 96 | 100 |

| Peak oxygen consumption (L/min) | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 0.90 | 1.60 |

| Maximum workload (watts) | 58.91 ± 10.87 | 50 | 105 |

| Workload at 60% VO₂peak (watts) | 35.35 ± 6.52 | 30 | 63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).