1. Introduction

Proper diet and physical training positively affect health and physical performance. Recent scientific knowledge has led to a better understanding of the different physiological mechanisms of performance. In particular, it has highlighted the role of various macro and micronutrients in energy supply, regulation of metabolism, and muscle contraction [

1].

The various research studies that have focused on

Moringa Oleifera (MO) have suggested the potential effect this plant could have on the diet of athletes. Indeed, the powder of MO leaves is a Phyto biotic, well known for its medicinal use [

2]. It contains phytochemicals, such as alkaloids and flavonoids, which provide immunomodulatory and antimicrobial properties [

3]. MO also includes many natural antioxidants (vitamin E and selenium), minerals (calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium), and phytochemicals such as caffeic acid [

4], which decrease fatigue and the perception of exertion during physical activity.

The positive effects of this part of the plant on sports performance could be due to its rich composition of calcium (known for its role in neuromuscular excitability functions) [

5], potassium (necessary for the control of muscle contraction as well as in the regulation of water between the intracellular and extracellular environment) [

6], in protein intake (effects on maintenance and increase in muscle mass) [

7]. The presence of flavonoids in the plant’s leaf could also contribute to improved athletic performance. They can modulate the activity of certain enzymes and modify the behavior of several cellular systems, suggesting that they could exert a multitude of biological activities, including significant antioxidant, vascular protective, anti-hepatotoxic, antiallergic, anti-inflammatory, anti-ulcer, and even antitumor properties [

8]. It has been reported that MO can be an ergogenic aid that improves energy metabolism in adult skeletal muscle. It increases the expression of critical metabolic markers, including those involved in glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial biogenesis, and angiogenesis in rats [

9]. It has also been reported that the aqueous extract of the leaves of this plant improves the swimming ability of rats by delaying the accumulation of blood lactate and urea nitrogen in the blood [

10]. The anti-fatigue potential of this herb may be expressed through mechanisms involving its antioxidant activity [

10]. This potential could be associated with increased hemoglobin concentration and hepatic and muscle glycogen stores. Not to mention, there is a reduction in lactic acid tissue accumulation by extracting this plant’s leaf [

10].

FitnoxT, which consists of 50% MO, has an antioxidant and vasodilatory effect on men aged 18 to 55. It also increased red blood cell count and dopamine levels (36%) from 225 μg/24h to 354 μg/24h in the blood before and after exercise in these individuals [

11].

Therefore, the present research aims to document the effect of MO leaf powder supplementation on cardiorespiratory endurance during exercise in athletes.

2. Results

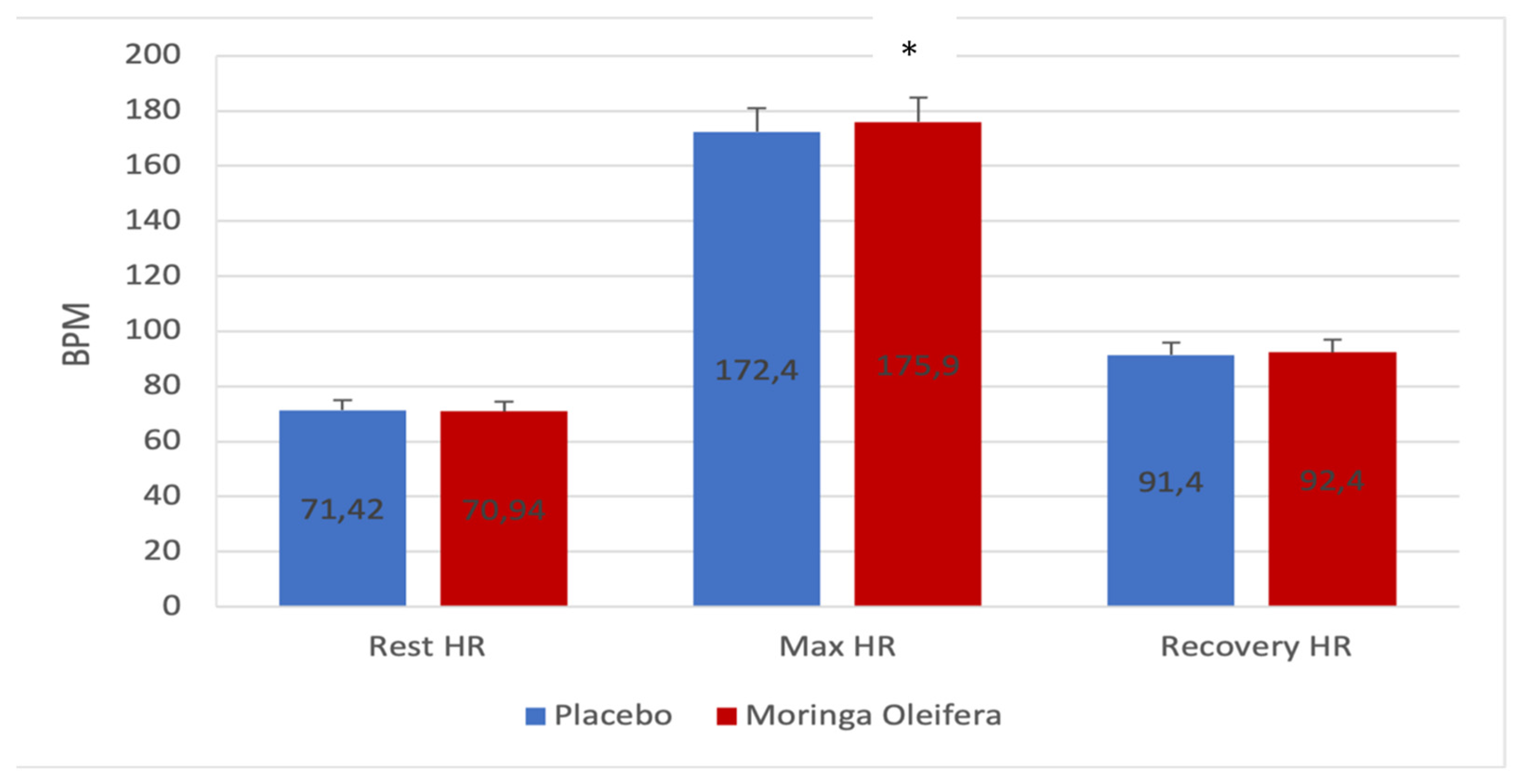

2.1. Effects of MO on Heart Rate

Figure 1 shows the resting heart rate, the highest heart rate on exertion, and the recovery rate before and after consumption of the MO infusion. Consumption of the MO leaf powder infusion did not induce a significant change in resting and recovery heart rate (Δ 71.42 ± 11.7 vs 70.94 ± 12.1; p=0.764; d=0.05

/ Δ 91.4 ± 15.9 vs 92.4 ± 15.0; p=0.625; d=-0.1 respectively). However, a significant increase was observed in the maximum heart rate during exercise (172.4 ± 22.5 vs 175.9 ± 23.1; p=0.02; d=-0.9). The MO, therefore, seems to allow an increase in the heart rate during exercise. This is not an anomaly since the increase was observed during training. However, at rest and 7 min after exercise, the heart rate remained similar in response to the two treatments (MO and Placebo). It can, therefore, be noted that in the presence of MO, the participants made a more intense effort, which led to an increase in heart rate.

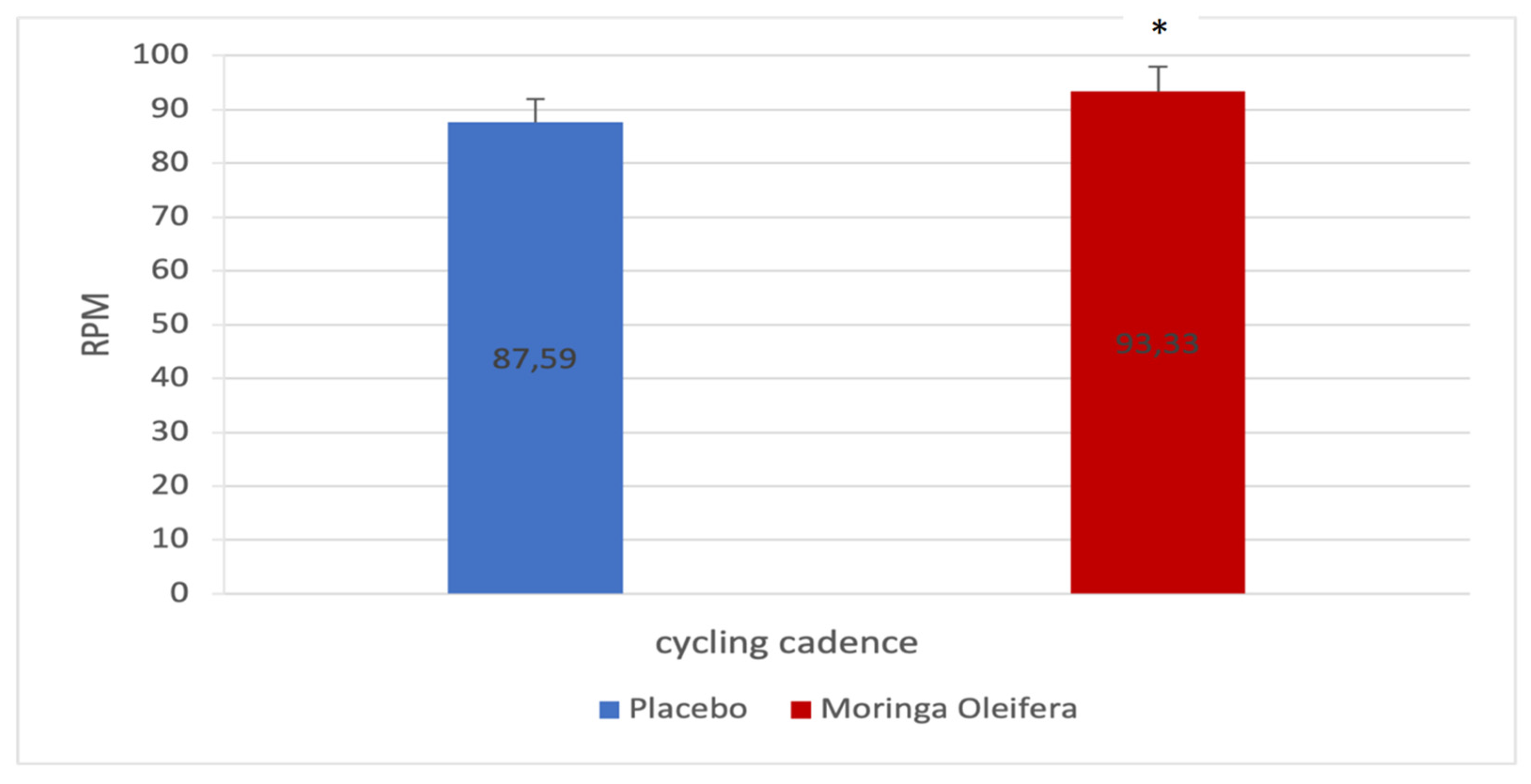

2.2. Effects of MO on the Average Pedaling Cadence

Figure 2 shows the average pedaling cadence before and after consumption of the MO infusion. There was a significant increase in the average pedaling cadence (Δ 87.6 ± 18.5 vs. 93.3 ± 15.8; p=0.008; d=-0.5) during the endurance test after consuming an MO leaf infusion compared to the placebo consumption.

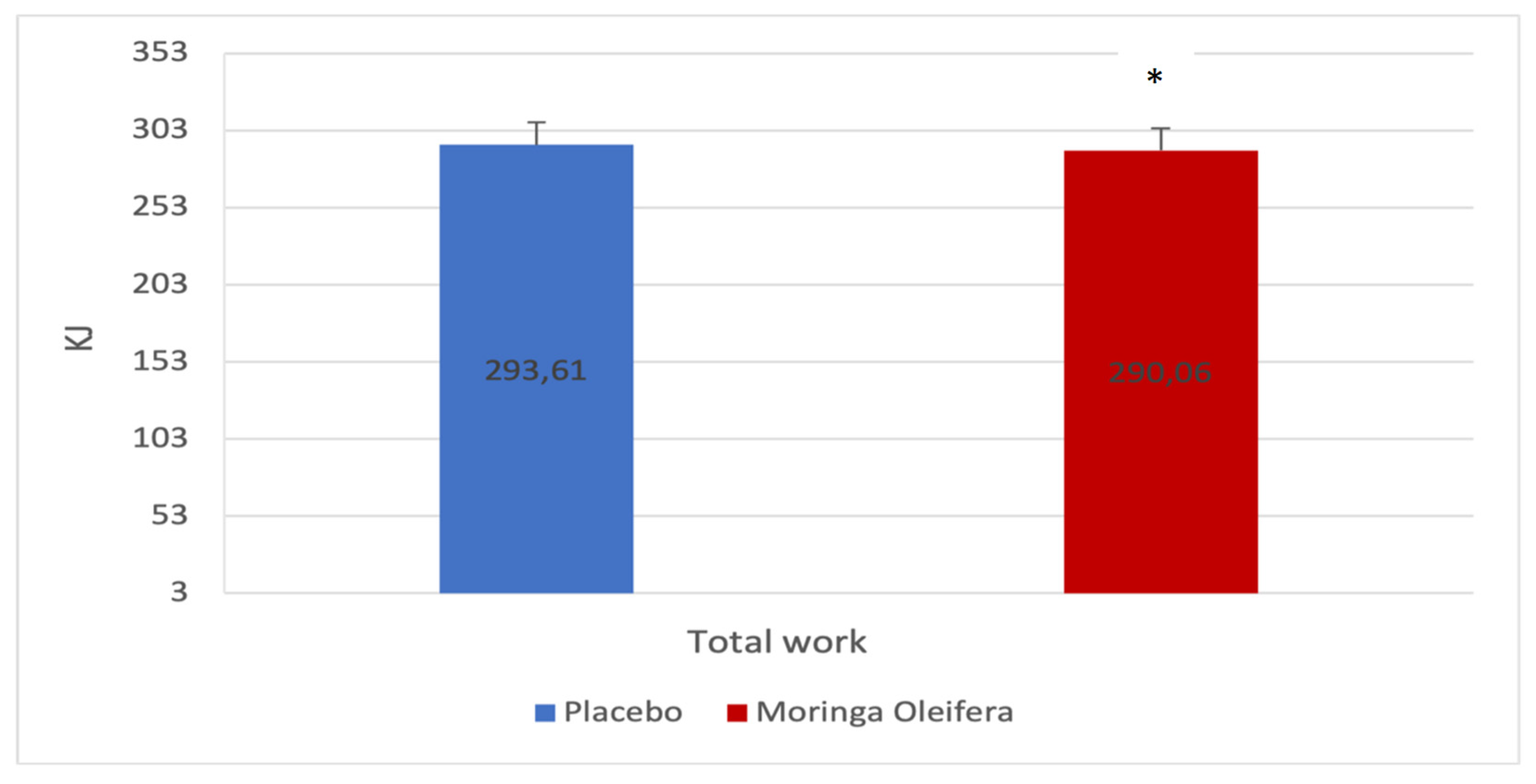

2.3. Effects of MO on the Total Work

Figure 3 shows the total work before and after MO infusion consumption. The energy supplied to perform the endurance test is significantly different (Δ 293.6 ± 75.3 vs 290.1 ± 77.4; p=0.012; d=0.5).

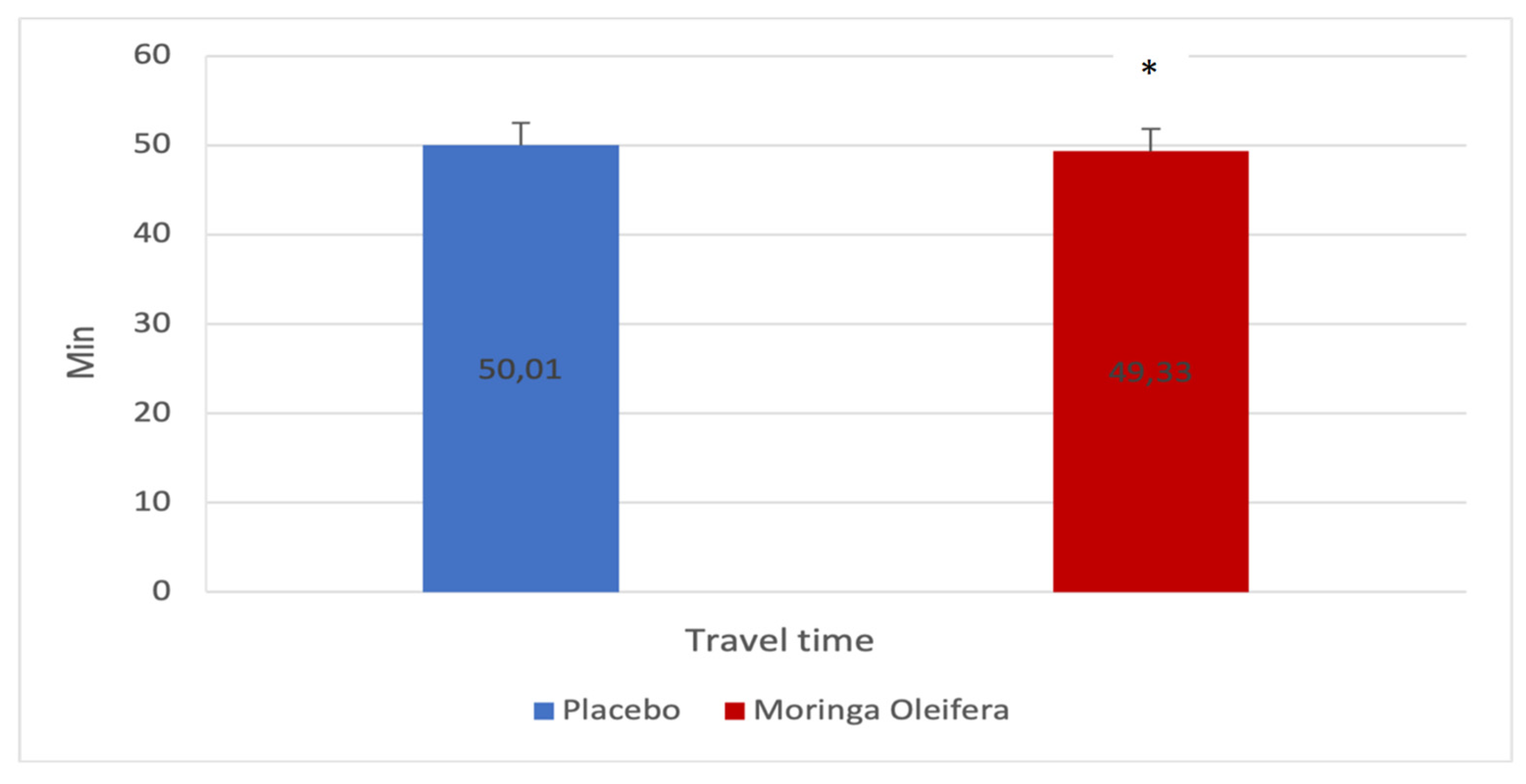

2.4. Effects of MO on the Travel Time

Figure 4 shows the travel time before and after consumption of MO infusion. There was a significant difference in the minutes needed to complete the endurance test (Δ 50.0±22.3 vs. 49.33±21.9; p=0.021; d=0.4). It would, therefore, seem that the consumption of MO favors the reduction of the time needed to complete the endurance test compared to the consumption of a placebo.

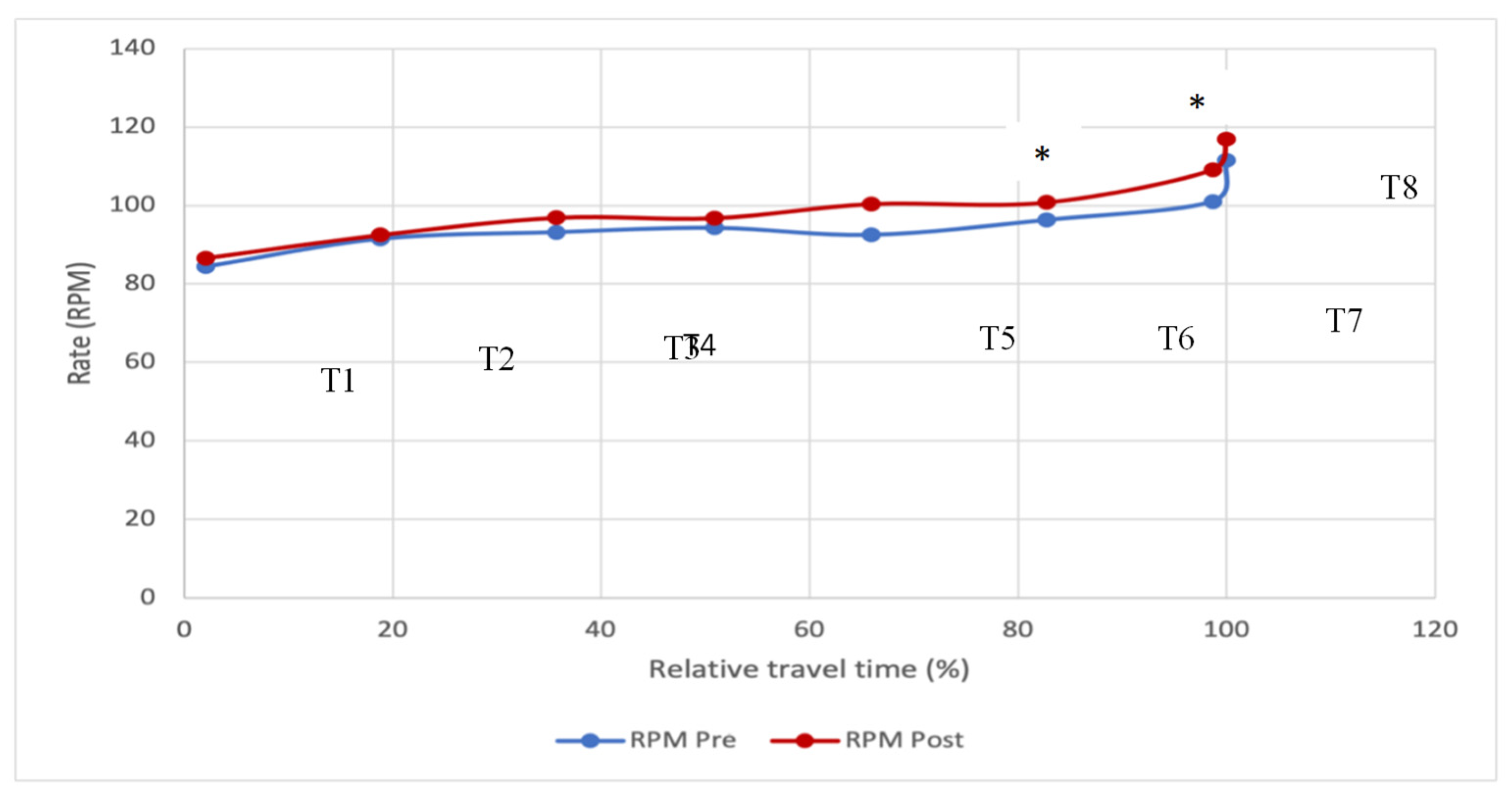

2.5. Effects of MO on the Pedaling Cadence with the Relative Travel Time

Figure 5 shows the pedaling cadence with the relative travel time before and after consumption of the MO infusion. This indicates that the strategy adopted by the participants seems to be the same before and after the consumption of MO: low cadence at the beginning, followed by a slight gradual acceleration. From T4 onwards, we observe a slight difference in the curve profiles, but this is not significant. Thus, the difference is significant between the two groups from time T6, corresponding to about 80% of the course, where we notice an increase in the pace until the end of the test (T7=100% for 33 participants). The T8 point, corresponding to only one participant who took longer than the others to finish the test, was not tested, so we cannot confirm the significance with and without MO.

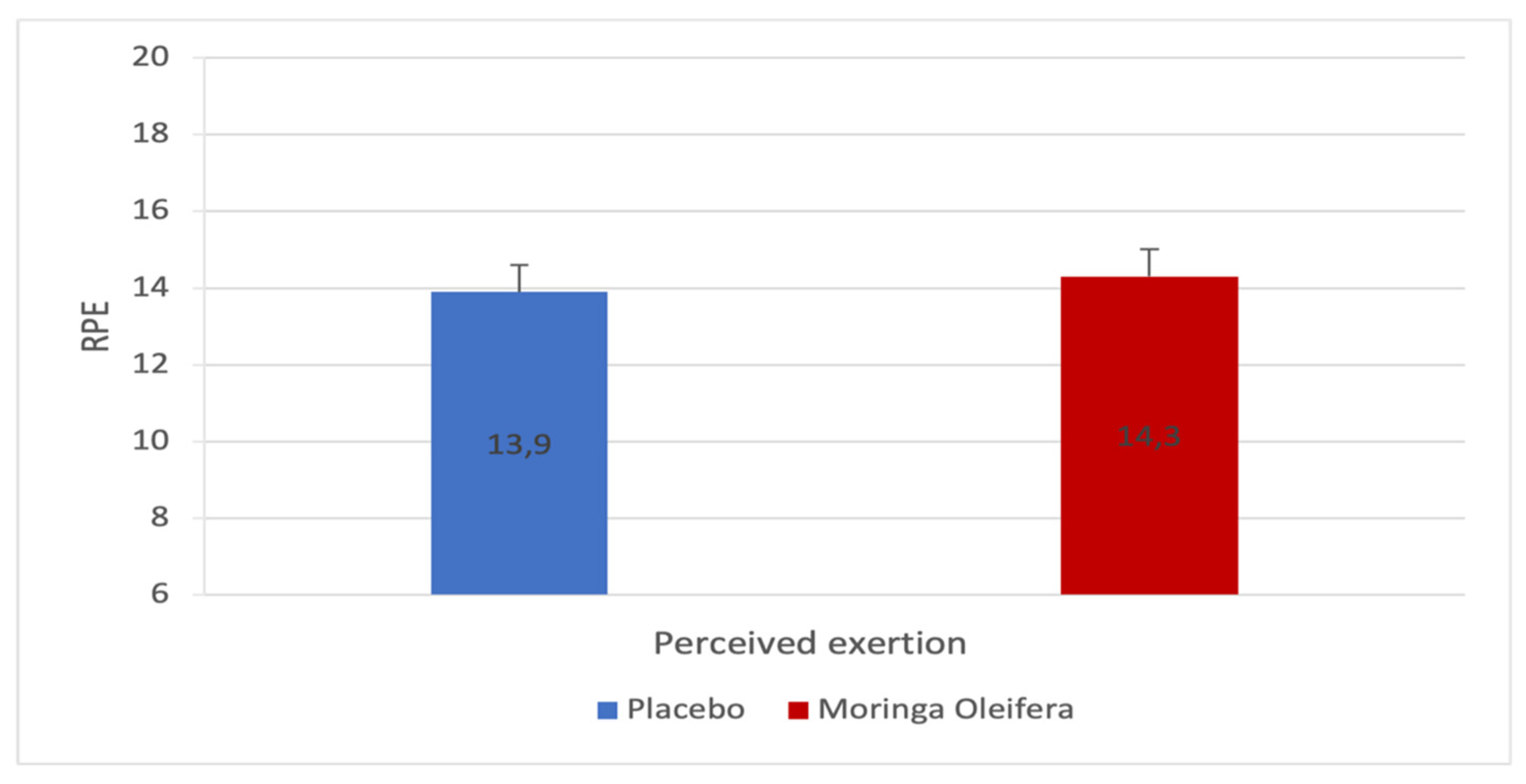

2.6. Effects of MO on the Rate of Perception of the Effort (RPE)

Figure 6 shows the participant’s perception of the effort estimated before and after consumption of the MO infusion. The RPE estimated by the participants at the end of the two tests was not significantly different (Δ 13.9 ± 2.8 vs 14.3 ± 2.5; p=0.357; d=-0.2). MO does not seem to affect participants’ perception of effort.

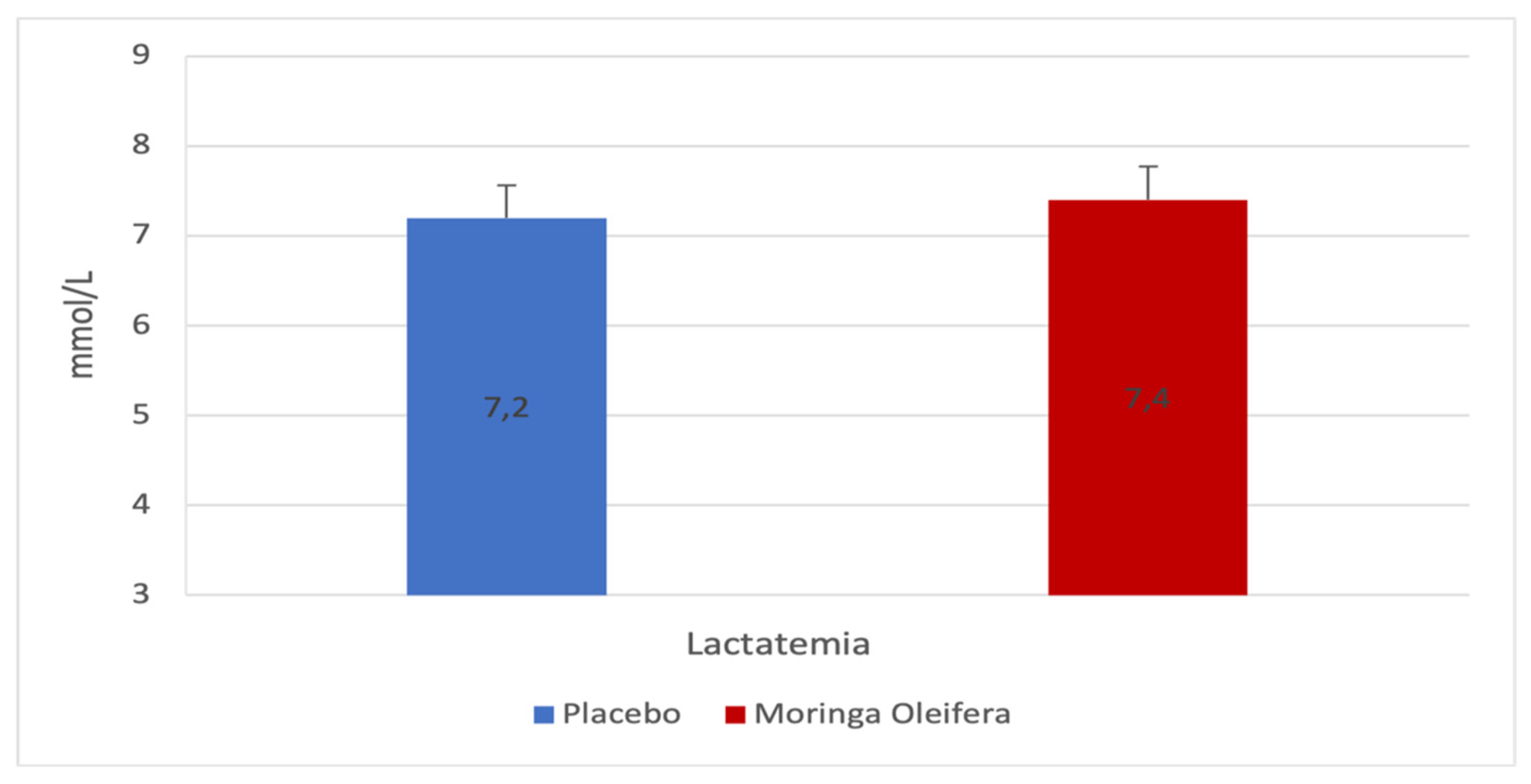

2.7. Effects of MO on the Blood Lactate

Figure 7 Blood lactate levels following endurance exercise do not reveal a significant difference between MO or placebo (Δ 7.2 ± 4.2 vs 7.4 ± 3.5; p=0.635; d=-0.1).

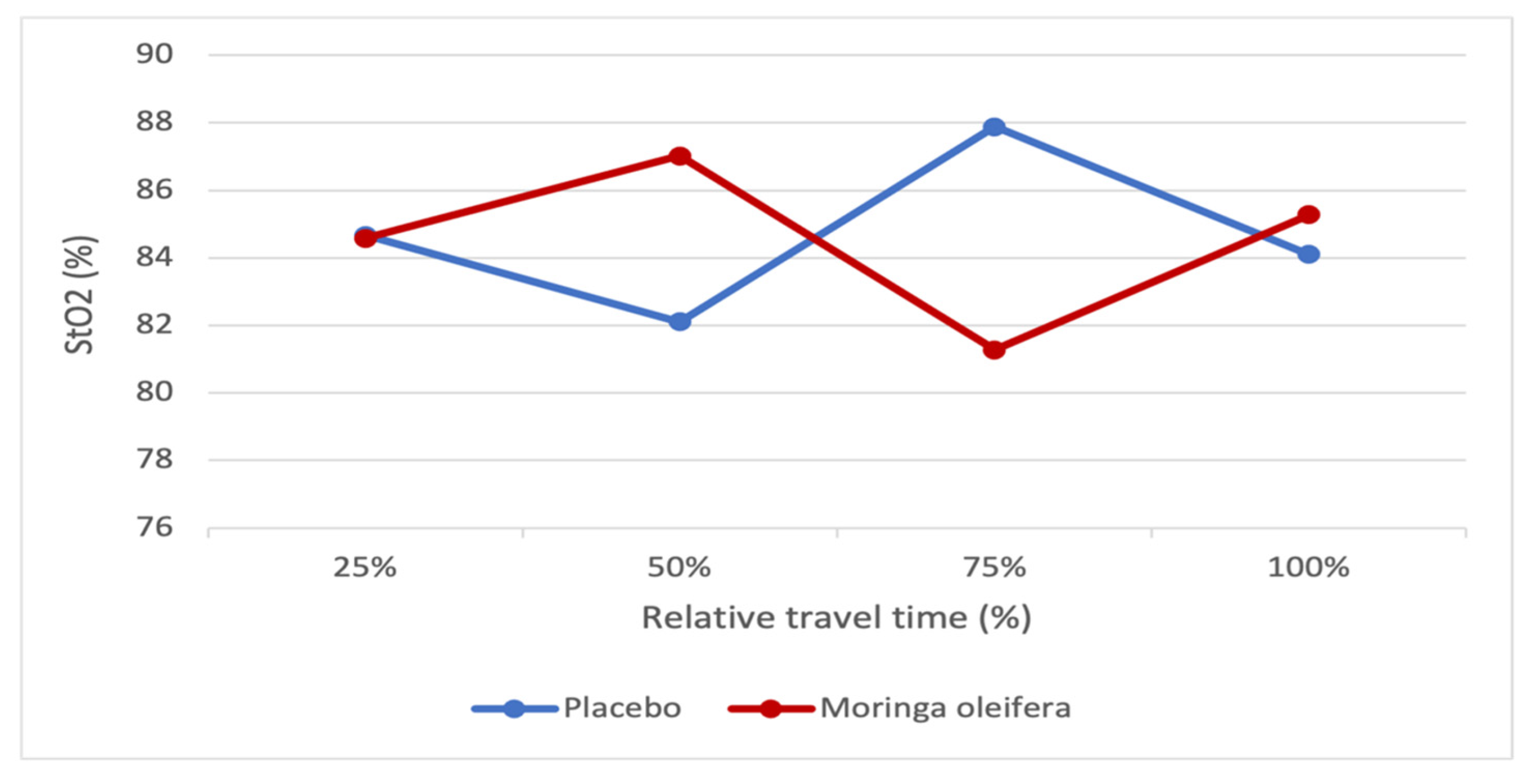

2.8. Effects of MO on Muscle Oxygenation

Figure 8 shows muscle oxygen saturation (SmO

2) and the relative travel time percentage before and after MO infusion consumption. We compared the values at 25, 50, 75, and 100% of the participants’ travel time before and after MO consumption. The figure shows that at 25% of the travel time, the SmO

2 is almost the same with and without MO. At 50 and 100%, there is a decrease in SmO

2 before MO consumption, while it increases after consumption. However, at 75%, muscle oxygen saturation is higher before than after MO consumption.

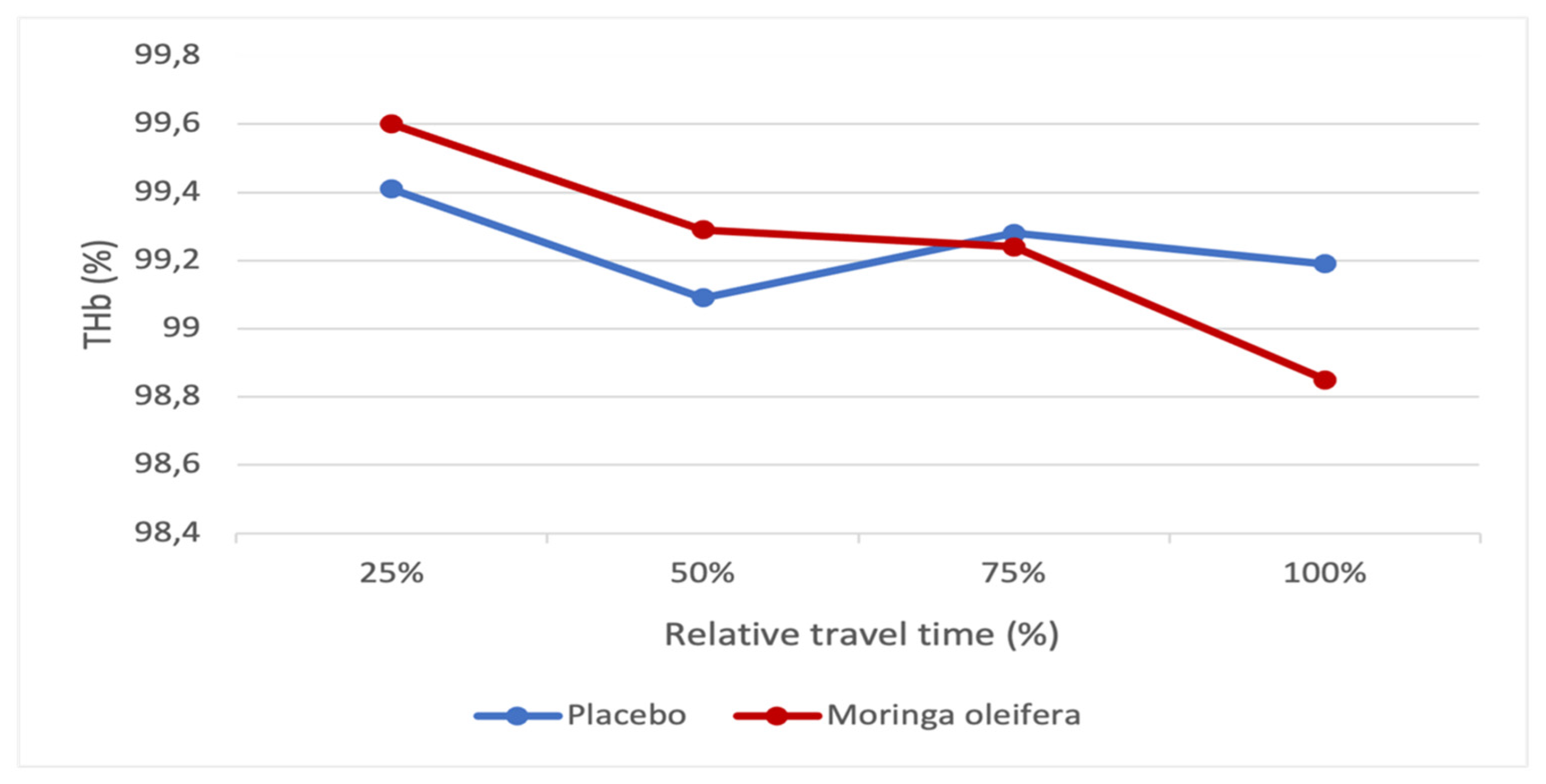

2.9. Effects of MO on the Total Oxygenated Hemoglobin

Figure 9 shows the total oxygenated hemoglobin (THb) level and the percentage of relative travel time before and after consumption of the MO leaf infusion. We compared the values at 25, 50, 75, and 100% of the participants’ travel time before and after MO consumption. The figure shows that the THB before MO consumption decreases by 25% to 50%. It increases slightly from 50% to 75%, then decreases slightly from 75% to 100%. However, after MO consumption, there is a gradual drop in THB from 25% to 100% of the travel time. Compared to each other, we observe that at 25% and 50%, the THB before consuming MO is lower than that after consumption. At 75% and 100%, the THB before consumption of MO remained higher than that after consumption. However, these differences are not significant and practically do not show any change in THb between the conditions of consumption and the absence of MO during the test.

Comparing

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, for the test performed in the absence of MO, the only increase in SmO

2 observed from 50% to 75% was accompanied by the rise in total oxygenated hemoglobin in the same period. The same was true for all times that a decrease in SmO

2 was observed, accompanied by a reduction in THb (25 to 50% and 75 to 100%). However, the test performed in the presence of MO shows that despite the constant decrease in total oxygenated hemoglobin, muscle oxygen saturation (

Figure 9) increased from 25% to 50% and from 75% to 100% of the time the test was performed. This shows that MO could extract oxygen better.

3. Discussion

The objective of the present study was to compare the performance before and after MO consumption in volunteers subjected to an endurance test. The results make it possible to test the hypothesis that the MO leaf improves endurance performance.

The MO allowed the participants to achieve a higher maximum heart rate during the endurance test. This goes in the opposite direction of our hypothesis. However, this could be explained by the intensity of the effort provided by the participants, which was higher during the endurance test. Indeed, during physical exertion, total peripheral vascular resistance (TPVR) decreases following vasodilation of the arterioles in active muscles via the effect of the orthosympathetic nervous system [

19]. Cardiac output (QC), dependent on stroke volume (ESV) and heart rate (HR), also increases with exercise. The increase in heart rate on exercise is explained by the fact that the duration of the cardiac cycle decreases with a duration of diastole time shorter than the duration of systole time and, therefore, a duration of ventricular filling time that is reduced [

19]. Then, the MO may act as a vasodilator, allowing a higher effort and thus causing an increase in heart rate to perform the same type of time trial (our protocol is described in the methodology section). The results of the study by Aekthammarat et al. (2020) on MO showed the plant leaf’s vasodilatory effect, which corroborates our observations [

20].

The total work (energy deployed to carry out the test) and performance (time) were significantly reduced, as advanced in our hypothesis. Thus, the infusion of the MO leaf decreased total labor and time following its consumption. This indicates that the MO leaf would increase efficiency and that it would be necessary to deploy less energy and time to perform the same exercise (i.e., here, to travel 20km with a fixed load). In other words, the infusion of the MO leaf could play a role in fighting fatigue. The participants’ pedaling cadence (RPM) intensified significantly with the MO. In addition, a decrease in the energy deployed and the time it takes to reach 20km are affected, indicating an improvement in efficiency. This set of acute adaptations supports the hypothesis that MO leaf infusion may have direct anti-fatigue properties on activated skeletal muscle. The RPM increased in the participants after consuming the MO infusion. Scientifically, this could be explained by the fact that the effort made by the participants after consuming the MO infusion was more intense (Increased pedaling cadence). Therefore, the fact that the RPM has increased, coupled with a decrease in total work required, possibly indicates a direct ergogenic effect on muscle performance. All of this is correlated with the results of several studies that have shown the anti-fatigue effect of the plant [

10], [

21,

22]. However, it cannot be ruled out that consuming an MO leaf infusion has a cognitive placebo effect. Nevertheless, our cross-referenced experimental design partially corrects the placebo effect.

Barodia et al. found that MO leaf extracts improved endurance and locomotor activity in rats [

19]. Our study allows us to affirm a similar effect in humans, as we saw a significant decrease in travel time and total work with the consumption of the infusion. It would also seem that the MO had a motor effect that favored the efficiency of the movement. This is justified by the significant increase in the pedaling cadence after consumption.

By relating the travel time relative to the cadence (RPM), it is possible to observe a beginning of divergence in terms of cadence between the two treatments from half of the travel time and a significant divergence of the RPMs at 80 and 100% of the route. In addition, even if the difference in cadence is not substantial at times T3 (35%) and T5 (65%), there is still a significant difference and an effect of the average size of the MO on the cadence at the end of the journey. The MO, therefore, seems to favor an increase in the pace at the end of an endurance trial and, thus, an improvement in endurance.

Muscle Oxygenation

The analysis of muscle oxygenation and related to the relative duration of the journey expressed as a percentage of travel time showed that in the presence of MO, it is observed that despite an appearance of a (non-significant) constant decrease in total hemoglobin, muscle oxygen saturation increased at the beginning and end of the effort. This could indicate better oxygen extraction by the muscle in the presence of MO. This observation is corroborated by the work of Eze et al. (2020), who revealed that MO has the potential to be an ergogenic aid through an improvement in energy metabolism in adult skeletal muscle by increasing the expression of critical metabolic markers (PGC-1α, PPARγ, SDHB, SUCLG1, VEGF, PGAM-2, PGK1 and MYLPF) [

9]. However, a recent study by Tsuk et al. showed that MO does not physiologically improve the endurance of young and healthy subjects [

23]. However, it should be noted that this is a pilot study in which the dosage, treatment time, and sample size were small compared to the methodology adopted in our research.

Despite this, the consumption of the MO leaf infusion did not result in a significant decrease in resting heart rate. We expected a reduction in heart rate induced by MO since the cardioprotective properties conferred by N,α-L-rhamnopyranosyl vincosamide (alkaloid) extracted from its leaves allow the reduction of the level of serum cardiac markers such as troponin-T, creatine kinase-MB following isoproterenol-induced cardiac toxicity [

24]. In addition, the aqueous extract of MO leaves has been shown to fight high blood pressure (decreased blood pressure and heart rate) in hypertensive rats. Indeed, it would cause better vasodilation by acting directly on the endothelium and, therefore, seems to be a natural product against hypertension [

20]. This could be due to high amounts of arginine in the MO leaf powder (160mg/100g) [

25]. The latter is credited with improving NO production in rats [

26].

The Rate of Perception of Effort (RPE) and Lactatemia

The result of the perception of effort did not verify our hypothesis. Yet, we expected to observe a decrease since Lamou et al.’s study showed that MO had anti-fatigue properties during a swimming test [

10]. In our research, it is possible that the increase in the rate following the consumption of MO tea acted to maintain a high RPE.

Lactate levels were also expected to decrease with MO consumption, as observed in the study by Lamou et al. [

10]. However, the blood lactate level after the MO leaf infusion was slightly higher than that obtained after the consumption of the placebo. This could be explained by the intensity of the effort made by the participants after consuming MO.

Limits

The possible limits of our study are of several kinds:

A small amount of data was collected for certain variables, specifically muscle oxygenation and lactatemia.

We followed up with the participants regarding compliance with the instructions based on their honesty in informing us in case of non-compliance. Perhaps the instructions were not followed entirely by the participants: forgetting to take a one-time dose, being associated with alcohol, and having modified daily habits. However, a few participants informed us of this, and their results were removed from the study.

Some of our participants were student researchers already used to this type of study. This may be a bias since they were not 100% blind and could try to adapt to the situation.

Pratical Applications

The following practical applications can be considered in the context of the use of moringa oleifera by athletes:

Enhanced Athletic Performance: Athletes can incorporate Moringa Oleifera leaf powder into their diets to improve endurance and overall performance during training and competitions.

Natural Supplementation: Coaches and sports nutritionists can recommend Moringa Oleifera as a natural alternative to synthetic supplements, providing athletes with a sustainable and health-friendly option.

Cardiorespiratory Benefits: The study’s findings could be used to develop targeted nutrition plans to optimize cardiorespiratory functions, aiding in faster recovery and enhanced stamina for endurance athletes.

Training Programs: Fitness professionals can integrate Moringa Oleifera supplementation into training regimens to enhance athletes’ endurance capabilities, tailoring programs to maximize the benefits observed in the study.

4. Materials and Methods

Subjects

Thirty-nine participants (22 men and 17 women) aged 18 to 35 were included. They were healthy and physically active (more than 150 minutes per week) and recruited through posters and mass emails. The first participants were also asked to bring the information to their loved ones. Smokers, alcohol users (more than two drinks per day), and individuals taking medications such as stimulants, opiates, hormone antagonists, and modulators are excluded from the study. The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee of the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQÀM) (2023-4759, multi-faculty CERPE). All participants were allowed to ask any questions to fully understand the requirements, benefits, and risks associated with this study before giving their informed approval. Participants agreed not to use medications, including vitamins and caffeine, a few days before the start of this study and during the period of the experiment. They also agreed not to change their eating and sports training habits during the study.

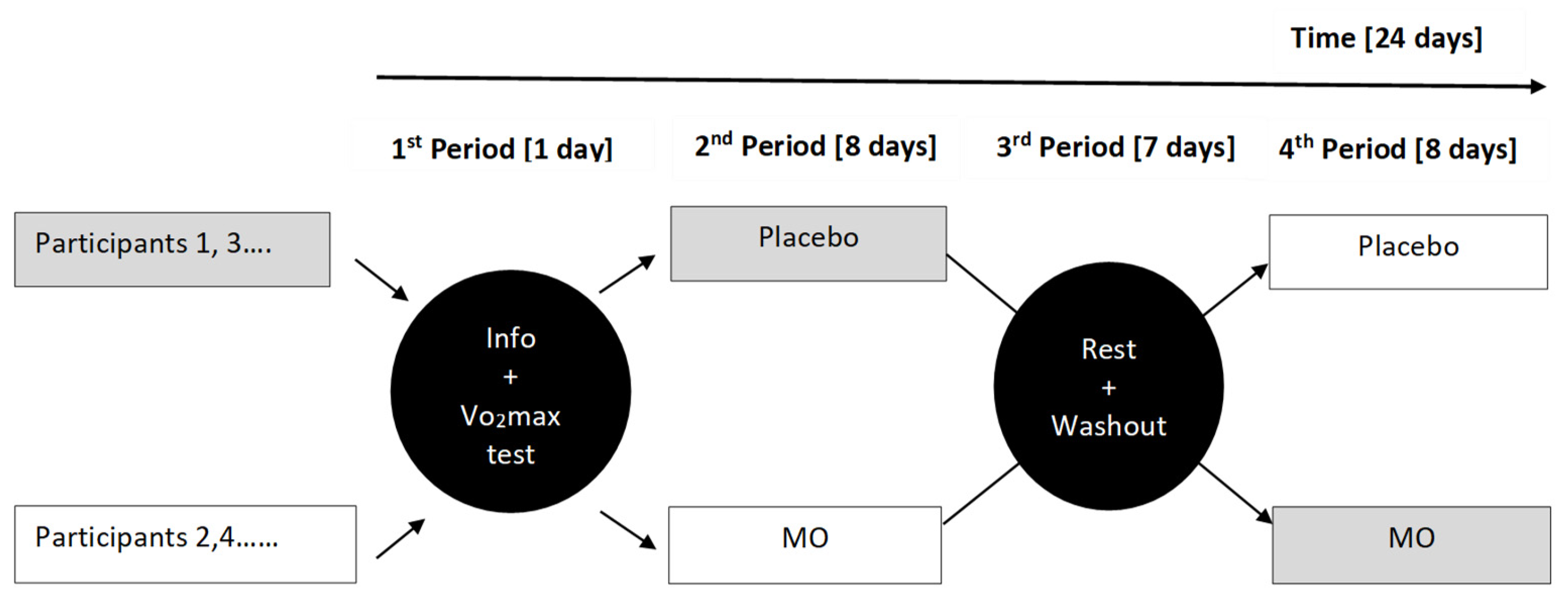

Design

This randomized clinical study consists of a group with a cross-over experimental design with the same subjects as their controls. The time a subject was involved in the trial was divided into three periods. The first period was one day and consisted of welcoming the participant to the laboratory to explain the project’s purpose and the experiments’ progress, then submitting him to the VO

2max test. During the remaining two periods, each participant received a double-blinded different treatment. The order of treatment created two groups with a size equal to half the number of participants included in the trial. Each participant’s order of application of the treatments (MO-Placebo or Placebo-MO sequence) was randomly determined. At mid-term, subjects in the treatment group (M, MO) were cross-crossed to join the treatment group (P, placebo). Ultimately, all patients went through each treatment group (

Figure 10).

1st Period (1 day): The participants were invited to the laboratory to learn about the experiments’ progress and then subjected to the VO2max test. The second half began the next day.

2nd Period (8 days): Both groups, after taking two doses of 200 ml of water (Placebo) or two doses of 200 ml of MO leaf tea (Treatment) per day for seven days, were subjected to sustained effort on the eighth day.

3rd Period (7 days): After the second period, participants had one week (7 days) of rest and weaning before the fourth period.

4th Period (8 days): During this period, we changed the order of treatment administration. After taking two doses of 200ml of water (Placebo) or two doses of 200ml of MO leaf tea (Treatment) per day for seven days, both groups were subjected to sustained effort on the eighth day.

The study was double-blinded. Opaque green containers were used to administer the various treatments to the participants. The study lasted 24 days.

Methodology

Tests and MeasurementsAnthropometric Measurements

The following parameters were measured: Height was measured using a stadiometer (Stadler), and body weight was measured using a Bio-impedance scale (Inbody 270).

Heart Rate Measurement

We measured the participants’ heart rate (HR) using a monitor (H10, Polar, Fi). Resting HR was measured for five (5) minutes in a seated position before the start of exercise. Then, it was recorded during both events (VO2 max and endurance) and for five (5) minutes after stopping the endurance exercise (post-exercise recovery period).

Measurement of the Maximum Volume of Oxygen Consumed (VO2max)

The primary objective of this test is to obtain the VO

2max and metabolic threshold (ventilatory threshold one and ventilatory threshold 2) using a progressive test until exhaustion on a stationary bike (Excalibur, Lode, SE) coupled with a metabolic cart system breath by breath (MetaMax, Cortex, DE). Indeed, each participant had a mask attached to their face and connected by a tube to the gas exchange measuring device. The exercise test was conducted as described by Lalonde et al. (2020). Before each test, the gas analyzers were calibrated with calibration gases (25% O

2 and N

2 balance and 16% O

2, 5% CO

2, and N

2 balance) and the air volume turbine with a 3 L syringe. The manufacturer provided the software to display VO

2max and other parameters (ver. 7.2.0.52, 2001-2011, Medgraphics Corporation, St-Paul, MN) [

15].

A five-minute warm-up was carried out before the incremental test on a stationary bike at a cadence of 90 repetitions per minute (rpm). The initial load was set at 25 watts (W) and, after two minutes, was increased to 50 W for the remainder of the warm-up period. At the end of the warm-up, the load was set at 25 W at the beginning, and then it was increased by 25 W every minute until exhausted while maintaining a minimum cadence of 60 RPM (rotations per minute), which could vary from 60 to 100 RPM. Participants should achieve two of the following four criteria to confirm VO

2max: an O

2 absorption plateau despite increased workload, a respiratory exchange ratio value >1.15, the predicted maximum heart rate achieved using the age equation 220 (if no V̇O

2 plateau was reached), or an inability to maintain pedaling cadence above 50 RPM [

16]. To obtain the moderate and high-intensity range, ventilatory thresholds 1 and 2 were visually determined as the point at which, during the incremental stress test, the ventilatory equivalent for O

2 (V̇E /V̇O

2) increases without any change in the ventilatory equivalent for CO

2 (V̇E/V̇CO

2) [

17]. At the end of the test, participants were asked to rate their perceived effort on a Borg scale [

18].

Endurance Test

HR and muscle oxygenation were also measured during the endurance event. The perception of the effort of the endurance test (EPR session) was also measured 20 minutes after the end of the test. The endurance event started with a warm-up period where the participant had to pedal at a comfortable cadence (60-120 RPM) for 3 minutes with a resistance of 50W. At the end of their warm-up, the resistance was increased to the level corresponding to their ventilatory threshold 1+10% (VT1+10%). The participants were then invited to complete a 20 km race against the clock as soon as possible. During the race, participants could see how far they had to go but were blinded to all other information. The time needed to complete the 20 km race was recorded. The total work, corresponding to the energy supplied (in kilojoules) to perform the exercise, was calculated using the formula:

Statistical Analysis

The results are presented as mean values ± the standard deviation. The normality of the results was verified using the Shapiro-Wilks test. The t-test for the matched samples was used to compare the mean of our different variables before and after the intervention. The significant difference was defined at p<0.05. The sample size was calculated using G-Power (ver 3.7) using 80% statistical power and a 5% improvement in endurance test performance. The required sample size was 34 participants. The analyses were carried out using the statistics software SPSS 27.0.

The study received approval from the institutional ethics committee of the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQÀM) (2023-4759, multi-faculty CERPE).

5. Conclusions

This study indicates that infusion of the MO leaf over seven (7) days improves endurance performance in young and active participants.

The infusion reduced the energy deployed and the time needed to cover the 20km by helping the participants maintain a higher effort. However, it did not significantly affect the other parameters studied: perception of effort (RPE), lactatemia, muscle oxygenation, and resting and recovery heart rate.

Given our observations on MO, it would be interesting to characterize better the mechanisms by which MO would influence our results and then study the potential effects the latter could have on skeletal muscle and its functioning. Also, check if MO increases products that are considered doping, such as octopamine and many others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.E.G, D.H.S, A.S.C, and G.D.; methodology, D.G.E.G, D.H.S, A.S.C, and G.D.; validation, D.G.E.G, D.H.S, A.S.C, and G.D.; formal analysis, D.G.E.G, D.H.S, A.S.C, and G.D.; investigation, D.G.E.G, and A.S.C.; resources, A.S.C; data curation, D.G.E.G, and A.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.E.G, D.H.S, A.S.C, and G.D.; writing—review and editing, D.H.S, A.S.C, and G.D.; visualization, D.G.E.G, D.H.S, A.S.C and G.D.; supervision, D.H.S, A.S.C and G.D.;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

To preserve the identity of the participants and the confidentiality of the research data obtained, the participants in this study are identified only by a code number. Following the requirements of the UQAM Ethics Committee, all information collected as part of this project is confidential. Only UQAM researchers who are associated with this project will be able to see the results of the tests. Research data is stored on a password-protected computer and USB key. The information consent form and test results will be kept in a locked filing cabinet in a locked UQAM office. Secondary use of data. The data collected in this study may be the subject of secondary studies. In this case, requests for access to this data will be evaluated and approved by a UQAM Research Ethics Board. Research data are stored securely.

Acknowledgments

The authors do not endorse the product based on the current study’s results. They would like to thank all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bielinski, R.W. Magnesium and physical activity. Rev Med Suisse. 2006, 2, 1783–1786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nkukwana, T.; Muchenje, V.; Masika, P.; Hoffman, L.; Dzama, K.; Descalzo, A. Fatty acid composition and oxidative stability of breast meat from broiler chickens supplemented with Moringa oleifera leaf meal over a period of refrigeration. Food Chemistry 2013, 142, 255–261. [CrossRef]

- Bukar, A.; Uba, A.; Oyeyi, T. Antimicrobial profile of Moringa Oleifera Lam. extracts against some food-borne microorganisms. Bayero Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2010, 3, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, B.; Oyedemi, S.; Masika, P.; Muchenje, V. Polyphenolic content and antioxidant properties of Moringa oleifera leaf extracts and enzymatic activity of liver from goats supplemented with Moringa oleifera leaves/sunflower seed cake. Meat Sci. 2012, 91, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppée, G. The Role of Calcium Ions in Neuro-Muscular Transmission. International Archives of Physiology 1946, 3, 323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lindinger, M.I.; Sjøgaard, G. Potassium Regulation during Exercise and Recovery. Sports Med. 1991, 11, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigard, A.X. Protein Intake and Muscle Mass. Science & Sports 1996, 4, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ghedira, K. Flavonoids: structure, biological properties, prophylactic role and therapeutic uses. Phytotherapy 2005, 4, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.M.; Mowa, C.N.; Wanders, D.; Doyle, J.A.; Wong, B.; Otis, J.S. Moringa oleifera improves skeletal muscle metabolism and running performance in mice. South Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 170, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamou, B.; Taiwe, G.S.; Hamadou, A.; Abene; Houlray, J.; Atour, M.M.; Tan, P.V. Antioxidant and Antifatigue Properties of the Aqueous Extract of Moringa oleifera in Rats Subjected to Forced Swimming Endurance Test. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3517824. [CrossRef]

- Gopi, S.; Jacob, J.; Varma, K.; Amalraj, A.; Sreeraj, T.R.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Divya, C. Natural sports supplement formulation for physical endurance: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Sport Sci. Heal. 2017, 13, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, H.; Betton, G.; Robinson, D.; Thomas, K.; Monro, A.; Kolaja, G.; Lilly, P.; Sanders, J.; Sipes, G.; Bracken, W.; et al. Concordance of the Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals in Humans and in Animals. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2000, 32, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomis TA, Hayes AW. Loomis Essentials of Toxicology (4th ed.). California, USA: Academic Press; 1996.

- Coz-Bolaños, X.; Campos-Vega, R.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; Ramos-Gómez, M.; Loarca-Piña, G.F.; Guzmán-Maldonado, S. Moringa infusion (Moringa oleifera) rich in phenolic compounds and high antioxidant capacity attenuate nitric oxide pro-inflammatory mediator in vitro. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 118, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalonde, F.; Martin, S.-M.; Boucher, V.G.; Gosselin, M.; Roch, M.; Comtois, A.S. Preparation for an Half-Ironmantm Triathlon amongst Amateur Athletes: Finishing Rate and Physiological Adaptation. Int J Exerc Sci. 2020, 13, 766–777.

- Beltz NM, Gibson AL, Janot JM, Kravitz L, Mermier CM, Dalleck LC. Graded Exercise Testing Protocols for the Determination of VO2max: Historical Perspectives, Progress, and Future Considerations. J Sports Med (Hindawi Publ Corp). 2016;3968393.

- A Dolezal, B.; Storer, T.W.; Neufeld, E.V.; Smooke, S.; Tseng, C.-H.; Cooper, C.B. A Systematic Method to Detect the Metabolic Threshold from Gas Exchange during Incremental Exercise. J Sports Sci Med. 2017, 16, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borg G, Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales. Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998.

- Barodia, K.; Cheruku, S.P.; Kanwal, A.; Menon, A.; Rajeevan, R.; Rukade, A.; Shenoy, R.U.K.; Prabhu, C.; Sharma, V.; Divya, K.; et al. Effect of Moringa oleifera leaf extract on exercise and dexamethasone-induced functional impairment in skeletal muscles. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2021, 13, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aekthammarat, D.; Tangsucharit, P.; Pannangpetch, P.; Sriwantana, T.; Sibmooh, N. Moringa oleifera leaf extract enhances endothelial nitric oxide production leading to relaxation of resistance artery and lowering of arterial blood pressure. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 130, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, R.; Ma, Y.; Dong, W.; Guo, C.; Gao, W. Anti-fatigue properties of the ethanol extract of Moringa oleifera leaves in mice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 5500–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.-N.; Bian, X.-Y.; Xu, Q.-G.; Dong, W.-Y.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Guo, C.-J. [Antifatigue effects of the composition of Moringa oleifera leaves and Polygonatum polysaccharide and its mechanisms]. Chinese Journal of Applied Physiology 2022, 38, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuk S, Engel A, Odem T, Ayalon M. Evaluation of the effects of commercial Moringa Oleifera supplement on physical fitness of young fit adults: A pilot study. Scientific Journal of Sport and Performance. 2023;1:44-51.

- Panda, S.; Kar, A.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, A. Cardioprotective potential of N,α-l-rhamnopyranosyl vincosamide, an indole alkaloid, isolated from the leaves of Moringa oleifera in isoproterenol induced cardiotoxic rats: In vivo and in vitro studies. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo, T. Effect of fertilization on the growth and production of local Moringa oleifera and Moringa oleifera PKM-l in the Cascades Region (Burkina Faso). Bobo –Dioulasso: Master’s thesis; 2014.

- Dudley, R.W.R.; Comtois, A.S.; St-Pierre, D.H.; Danialou, G. Early administration of L-arginine in mdx neonatal mice delays the onset of muscular dystrophy in tibialis anterior (TA) muscle. FASEB BioAdvances 2021, 3, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).