1. Introduction

The obesity epidemic has partly stemmed from increased calorie consumption and reduced physical activity levels. [

1]. Of particular interest has been the role that resistance training can play in maintaining a healthy body weight and good overall health.

Resistance training, which includes strength and power exercises that stimulate skeletal muscle, has garnered interest for its role in maintaining a healthy body weight and overall health. This type of training has been shown to enhance muscle strength and mass, reduce body fat and blood pressure, lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, increase high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, help prevent osteoporosis, and reduce the risk of metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes by stabilizing blood glucose and insulin levels [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Despite these documented benefits of resistance training, many people tend to favor aerobic exercises or high-intensity interval training when aiming to lose weight and reduce fat mass. In contrast, competitive bodybuilders focus on resistance training and building lean mass to reduce fat mass. They often follow a dietary protocol that includes a bulking cycle (i.e., high caloric and protein intake) followed by a cutting cycle (i.e., reduced caloric intake with maintained protein intake). This approach helps them gain lean mass while lowering fat mass. While it is uncertain if this combined resistance training and dietary bulk-and-cut protocol is feasible and beneficial for untrained individuals, exploring this method could provide a viable alternative for weight loss and overall health improvements in the general population. Therefore, we designed a pilot study to examine the feasibility and effects of a novel 24-week resistance training intervention combined with a dietary protocol, consisting of bulk and cut cycles, on body composition, blood lipids (triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL) and inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and the anti-inflammatory interleukin (IL-10) in untrained adult males. To confirm the preliminary efficacy of this newly designed intervention, secondary outcomes also included muscle strength and VO2max (cycle ergometer).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 12 adult males, aged 25-45 years, free from any chronic conditions, and nonsmokers were recruited to participate in this pilot study. One of those dropped out before starting the intervention, thus attaining a final sample of 11 participants (mean age: 33.0 ± 3.0 y; mean height: 180 ± 6 cm). To be included in the study, participants must have had no prior experience with any structured strength training program (i.e., never worked with a personal trainer) and were not taking any medications related to a chronic condition or any supplements to aid in training adaptations (e.g., performance-enhancing drugs like steroids) or any nutritional supplements (e.g., vitamin D, calcium, creatine). Moreover, participants were free from any substantial injuries over the past year and did not suffer from any ailment or conditions for which exercise, and maximal exertion efforts may be contraindicated (e.g., chronic low back pain, arthritis, neuromuscular diseases). Specifically, criteria from the American College of Sports Medicine and American Heart Association [

8] were used to determine contraindications to aerobic and resistance training/testing including recent myocardial infarction or electrocardiography changes, complete heart block, acute congestive heart failure, unstable angina, and uncontrolled hypertension. Participants were excluded if they were on a restrictive dietary lifestyle that would require substantial alterations to participant nutritional intake (e.g., vegan, vegetarian) and/or any eating disorders (e.g., bulimia, anorexia).

All participants agreed to participate in this study by signing a consent form. The study was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethics approval from the Brock University Research Ethics Board (REB #22-135).

2.2. Study Design and Procedures

The pilot intervention study used a within-subject design where all participants were exposed to the same intervention. Participants visited the Applied Exercise Physiology Lab (Brock University) four times; first for a preliminary meeting, followed by three assessment visits which occurred before the start of the intervention (week 0), at the end of the bulking cycle (week 12) and at the end of the cutting cycle (week 24). All these visits were scheduled in the morning between 800 and 1100 hours to control for any circadian effects.

During the preliminary visit, participants were informed on the purpose, procedures, risks of the study, educated on the style of training (i.e., types of exercises, reps/sets) and types/quantities of foods they would be allowed to consume. They also completed questionnaires on their medical history, physical activity, and dietary habits [

9].

All assessment visits at weeks 0, 12 and 24 followed the same protocol starting with a fasted baseline blood draw followed by anthropometric and body composition measurements. Specifically, height was measured with a stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm with no shoes, and body composition was measured via air displacement plethysmography (BodPod; Life Measurement Inc., Concord, CA, USA) to get measures of body mass (kg), fat mass (kg), fat-free mass (kg) and percent body fat (%). During these visits, participants also performed an incremental exercise test to exhaustion on the bicycle ergometer (Lode, 911905, Netherlands) to determine their maximal aerobic capacity (VO2max). Participants began the test with a 2-min warm-up at a workload of 100 Watts then continued with an incremental 25-Watt increase in workload applied every minute until volitional fatigue. Following completion of the test a 3-min cool-down period was performed. Oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) were measured continuously with a gas collection system (MAX-II, AEI Technologies, PA, USA). Heart rate (HR) was continuously recorded using an integrated HR monitor (Omron, HR-310, USA).

In addition to the above measurements, three strength testing sessions were scheduled separately at the Core Health Collective Centre during weeks 0, 12 and 24. During these sessions, participants underwent strength testing using the following exercises: squat, chest press, deadlift, and seated row. The testing was supervised and included several practice sets building up from 40-50% of 1RM and progressively adding weight until 1RM was determined. There were 2–3-min rests between sets. If after 5 sets a 1RM was not determined, then it was calculated using O’Conner’s equation [

10] [(1-RM = weight x (1+(0.025 x reps)].

2.3. Dietary Protocol

2.3.1. Bulking Cycle (Weeks 1-12)

During the first 12 weeks (3 months), daily caloric intake was determined on an individual basis using the Mayo Clinic Calorie Calculator which considers age, height, weight, sex, and daily activity levels [

11]. Based on their individual daily caloric needs, participants were instructed to consume a slightly hyperenergetic diet (~15% more calories/day than suggested by the Calorie Calculator). Importantly, participants were instructed to consume 25-30% of those calories from protein, 55-60% from carbohydrates, and 15-20% from fats. This breakdown falls within the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (AMDRs) recommended by Health Canada [

12]. An emphasis was placed on whole foods, but sustainability and balance were also taken into consideration, and thus, a 80/20 rule was employed (i.e., 80% whole foods, 20% foods of personal choice), but always aiming for the daily caloric allotment. To this end, participants were provided with a food scale to measure portion sizes and were educated on how to use the scale and the macronutrient make-up of common foods/beverages. Although not mandatory, to ensure consistency, we recommended the LeanFit whey protein (

Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada) to whoever chose to use a protein powder as part of their increased protein diet. Additionally, participants were provided with a journal to log their daily dietary consumption and checked on twice weekly to ensure they were adhering to the diet.

2.3.2. Cutting Cycle (Weeks 13-24)

During weeks 13-24, participants’ daily caloric intake was reduced initially by 200 calories from that consumed during the bulking cycle. They were weighed each week aiming to lose a ½ pound of body mass per week. If this was achieved, they stayed on the same 200-calorie deficit. If, however, a ½ pound was not lost over the week, an additional 200 calorie deficit was implemented. These weekly check-ins and calorie adjustments were maintained for the entire 12 weeks. There was no restriction on water intake. Participants were provided with a food scale to measure portion sizes and be educated on how to use the scale and the macronutrient makeup of common foods/beverages. Additionally, participants were provided with a journal to log their daily dietary consumption and checked on twice weekly to ensure adherence to the diet as well as address any concerns they may have had.

2.3.3. Dietary Assessment

Participants recorded all food and beverages throughout the entirety of the study using an app or dietary journal of their choice. We recommended participants use MyFitnessPal application (San Francisco, California, USA) as it is free and easy to use. Food records were then shared and analyzed for 7 consecutive days during both the bulking and the cutting cycles and percent adherence to each cycle was calculated using these records [

13,

14]. Diet adherence was calculated for each participant using the following equation: 7-day recorded calorie sum / 7-day target calorie sum x 100.

2.4. Resistance Training Sessions

This study consisted of a novel resistance training intervention designed for the study to include three resistance training phases (muscle hypertrophy, muscle strength, muscle endurance) as described below. The training was scheduled twice per week, on non-consecutive days, at the Core Health Collective Centre (St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada). All training sessions were led and supervised by a trainer and included three distinct resistance training phases (each 4 weeks in duration) during both the bulking and cutting dietary cycles for a total of 24 weeks. Throughout the 24 weeks, an emphasis was placed on compound exercises including squats, deadlifts, lunge variations, bench press, overhead press, pull-ups, and row variations. As a secondary consideration, accessory exercises such as bicep curls, triceps pushdowns, lateral shoulder raises, calf raises, and core work were also included. Each workout over the 24-week program was a full-body workout and included 3 compound movements followed by 2-3 accessory movements based on the trainer’s discretion (e.g., fatigue level of the participant). Since participants had 2 training sessions/week, workouts were designed in a manner where individuals performed one hip or knee dominant movement on alternating days (e.g., Workout #1 = squats, Workout #2 = deadlift), an upper body horizontal or upper body vertical pushing movement on alternating days (e.g., Workout #1 = dumbbell press, Workout #2 = overhead press) and a compound pull (e.g., seated cable row, pull-ups) each workout. There was no emphasis placed on the order of the exercises, although compound movements were performed before the accessory ones. In terms of the structure of the sessions, these involved groups of 1-3 participants at a time being led through the training and were scheduled based on participant availability.

As mentioned above, the intervention involved three resistance training phases. The first phase (weeks 1-4 and 13-16) was a hypertrophy phase, initially meant to familiarize participants with various exercises and correct form. Participants performed 3 sets of 8-12 repetitions of every exercise (a total of 5-6 exercises) starting with a safe baseline load. As the weeks proceeded, the goal was to progressively overload, and an emphasis was placed on increasing the load for each exercise.

The second phase (weeks 5-8 and weeks 17-20) of the training was a strength phase where a greater focus was placed on eliciting maximal strength. Participants executed 3-5 sets of 3-6 repetitions per exercise (i.e., more sets, lower reps). The exercises selected in this cycle were tailored for maximal strength efforts and included bilateral movements where more weight could be lifted (e.g., squats, barbell bench press).

The third phase (weeks 9-12 and weeks 21-24) of training was a muscle endurance phase with an emphasis on more supersets (i.e., performing multiple exercises consecutively with a very short rest period). Participants performed 3 sets of 15-20 reps for each exercise to increase heart rate and blood flow to the muscle. During this phase, participants may have been asked to perform hip and knee dominant movements in the same workout (e.g., super-setting squats and kettlebell swings) or even combine push and pull movements in a superset.

Finally, participants were asked to abstain from any strength exercise/training outside of that conducted for the study. Compliance with the 24-week training program was calculated as [training sessions completed / total training sessions] x 100.

2.5. Blood Analysis

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast of 10–12 h from the antecubital vein at three different time points: at baseline (week 0), the end of the bulking period (week 12) and the end of the cutting period (week 24). For each sample, 10 mL of blood was collected. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000rpm for 10 min at 4°C and the serum was aliquoted into air-tight Eppendorf tubes and stored in a locked freezer at -80˚C until analysis.

Blood lipids, including triglycerides, total cholesterol and HDL were measured in serum using a standard lipid panel, and low-density cholesterol (LDL) was calculated using the Friedewald equation [

15] by a diagnostic laboratory (LifeLabs, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The circulating concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6, and the anti-inflammatory IL-10 were analyzed in serum using a commercially available ELLA kit (cat. # SPCKE-PS-010895; ProteinSimple, San Jose, California, USA). This method analyses each sample in triplicate. All samples were run using Simple Plex software Runner and Explorer (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) analysed in one single plate. The intra-assay coefficients of variation (%CV) for TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 were 2.54%, 4.6% and 6.69%, respectively.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The data were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and z-scores for skewness and kurtosis. We used repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine changes in all variables across time (i.e., week 0, week 12, week 24). In the case of a significant main effect for time, post hoc comparisons using paired

t-tests were performed. Effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (

pη

2) for ANOVA and Cohen’s d for significant

post hoc comparisons and were interpreted based on the Cohen’s criteria for

pη

2: 0.01– 0.05 = small, 0.06 – 0.13 = moderate, 0.14 and over =large effect; and for d: 0.2 – 0.49 = small, 0.5 – 0.7 = medium, 0.8 and over = large effect [

16,

17]. Data are reported as means ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05 and performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Feasibility of the Intervention

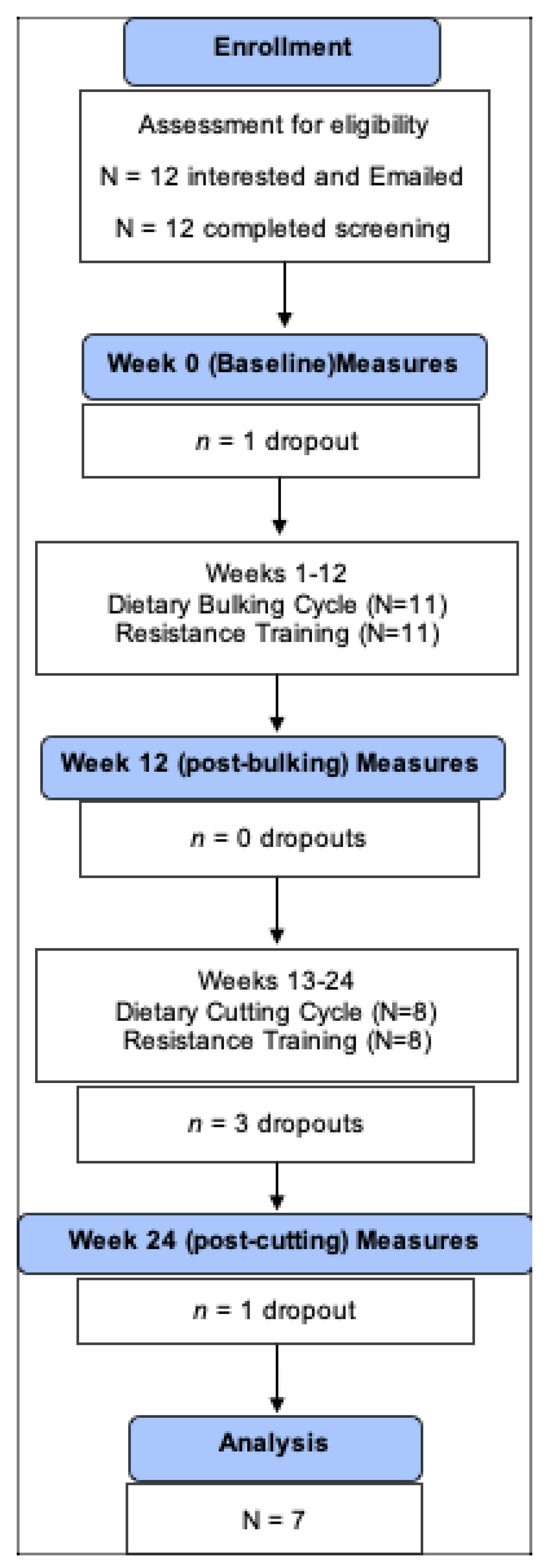

Of the 11 participants who started the intervention, three dropped out of the study during the cutting phase, two due to relocation and one for reasons unknown. One participant completed the 24 weeks of intervention but missed the last, post-cutting assessment for reasons unrelated to the intervention. Therefore, a total of 7 participants, completed the 24-week intervention, attended all 3 assessments and were included in the study, which is a retention rate of 64%.

Figure 1 illustrates the study enrollment.

The mean age of these 7 participants was 33±4 years. At baseline, participants were classified with obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) having a mean BMI 35.0 ± 4.6 kg/m2. Compliance with the 24-week resistance training program among the 7 participants was 96.7±4.3 %. Adherence to the 12-week bulking and 12-week cutting cycles of the dietary regimen was 93.7±5.1 % and 94.5±3.0 %, respectively.

3.2. Efficacy of Resistance Training

Strength significantly improved over time with large effect sizes observed (

Table 1). The deadlift and squat exercises both showed significant main effects for time (F=46.7, p<0.001,

pη

2=0.90; F=44.0, p<0.001,

pη

2=0.90, respectively), with increases from baseline to week 12 testing and then plateaus, such that week 24 values were still significantly higher than baseline, but not significantly higher than week 12 values. Specifically, the weight of the deadlift showed a progressive 40% increase from baseline to week 12 (p<0.001, d=2.70), with 24-week values 46% higher than baseline (p<0.001, d=3.21). The same was observed for the squat, which showed a considerable 56% increase from baseline to week 12 (p<0.001, d=2.55) with 24-week values reaching 65% above the baseline (p<0.001, d=4.44). The bench press and seated cable row exercises also showed significant main effects for time (F=22.39, p<0.001,

pη

2=0.82; F=22.2, p<0.001,

pη

2=0.82, respectively), with significant increases from baseline to week 12, and then continued significant increases from week 12 to week 24. Specifically, bench press weight showed a significant 15% increase from baseline to week 12 (p=0.004, d=1.68) and a further 6% significant increase from week 12 to week 24 (p=0.018, d=1.42) reaching a 22% (p=0.02, d=1.88) overall improvement from baseline. Likewise, weight lifted in the seated cable row significantly increased by 23% from baseline to week 12 (p=0.001, d=2.12) and a further 5% significant increase from week 12 to week 24 (p=0.013, d=1.54) reaching a 28% overall improvement (p=0.005, d=1.95) from baseline (

Table 1).

As per

Table 1, we found no significant main effect for time for absolute VO

2max (F=1.5, p=0.27,

pη

2=0.23), or VO

2max adjusted for FFM (F=0.39, p=0.69,

pη

2=0.07).

3.3. Body Composition

There was a significant main effect for time for body mass (F=5.2, p=0.02,

pη

2=0.46), which significantly increased from baseline to week 12, i.e., post-bulking (+3%, p=0.01, d=1.32) and then significantly dropped from week 12 to week 24, i.e., post-cutting (-3%, p=0.02, d=1.22) back to its baseline value (

Table 2). Fat-free mass also showed a significant main effect for time (F=14.9, p<0.001,

pη

2=0.71), with a significant 4% increase from baseline to week 12 (p=0.003, d=1.76), and then a plateau such that week 24 values were still 3% higher than baseline (p=0.004, d=1.50) but not significantly different than week 12. Although fat mass at 24 weeks was about 9% lower than baseline, there was no significant main effect for time (F=3.2, p=0.76,

pη

2=0.35). However, and importantly, there was a significant main effect for time for relative body fat (F=4.0, p=0.046,

pη

2=0.40), which significantly decreased from week 12 to week 24 (-4%, p=0.03, d=0.86), reaching values 6% lower than baseline (p=0.01, d=1.20) (

Table 2).

3.3. Circulating Lipid Concentrations

The absolute values for lipid concentrations are presented in

Table 3. Analysis revealed no significant main effect for time for any of the lipid measures, including triglyceride concentrations (F=0.81; p=0.46;

pη

2=0.119), total cholesterol (F=1.05; p=0.36;

pη

2=0.15), HDL cholesterol (F=0.77; p=0.45;

pη

2=0.11) and LDL cholesterol (F=1.08; p=0.34;

pη

2=0.153). These findings suggest that lipid levels remained relatively stable over time. There was also no significant main effect for relative lipid changes (

Figure 2).

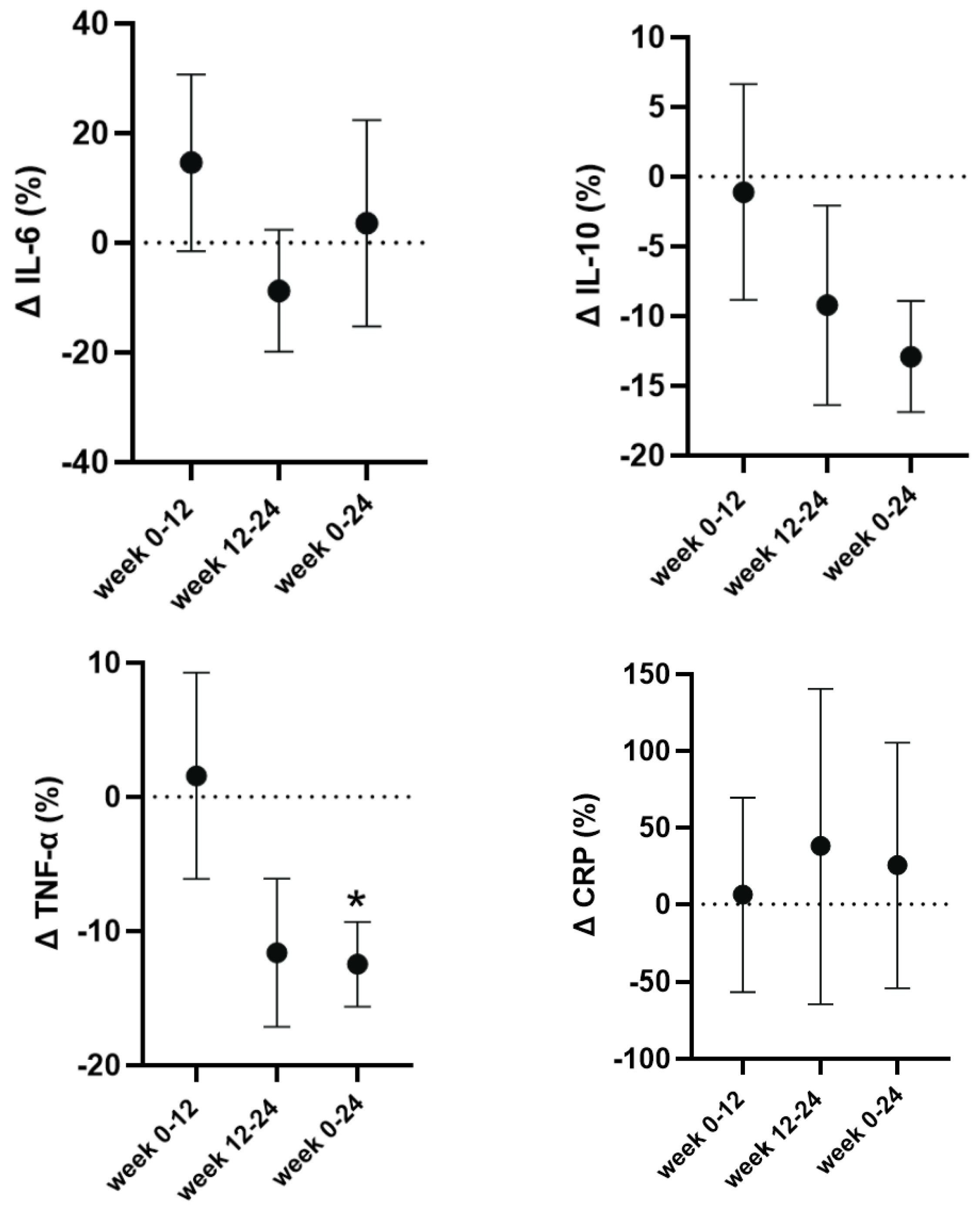

3.4. Circulating Inflammatory Markers

The absolute values for inflammatory markers can be found in

Table 4. CRP showed no significant main effect for time (F=0.12; p=0.87;

pη

2=0.01), and likewise, there was no significant main effect for time for IL-6 (F=0.55; p=0.59;

pη

2=0.08) or IL-10 (F=2.26, p=0.15,

pη

2=0.27). However, we observed a significant and large main effect for time for TNF-α (F=3.88, p=0.05,

pη

2=0.39), which at week 24, i.e., post-cutting had significantly lower concentrations compared to baseline (-15%, p=0.008, d=1.47) and to week 12 (-15%, p=0.04, d=0.96) (

Table 4). To account for the typical individual variability in absolute concentrations, we also present the percent CRP and cytokine changes in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to pilot a novel 24-week resistance training intervention combined with a bulk-and-cut dietary protocol in untrained adults with obesity. In general, the feasibility of the pilot study was confirmed by a 64% retention rate and excellent compliance and adherence to the 24-week training and dietary cycles. In terms of its preliminary efficacy, the results show that the 24-week intervention led to improvements in body composition marked by a significant increase in fat-free mass, and a decrease in body fat percentage, which was accompanied by significant increases in strength, irrespective of the decrease in caloric intake during the cutting cycle. Additionally, TNF-α had a significant overall decrease from baseline to post-cutting indicating reduced inflammation. However, no changes were observed in lipids, CRP, IL-6 and IL-10.

4.1. Intervention Feasibility

The purpose of this pilot 24-week novel intervention was to tailor a body building program that combined resistance training with bulking and cutting dietary cycles to be feasible for middle-aged, untrained men. The retention was 64%, which is high given the length and invasiveness of the intervention with most of the participants dropping out near the end, i.e., during the cutting cycle. Most of the dropouts in this study were due to participants relocating, making the commute to the gym difficult. The compliance to the training for our group of untrained men (living with overweight and obesity) was 96.7± 4.3 % with an adherence of 93.7 ± 5.1 % and 94.5 ± 3.0 % to the respective bulking and cutting cycles. All training sessions were supervised by both a personal trainer and a researcher, which led to not only the excellent compliance but ensured participants were performing all exercises properly and safely. Exercises were taken near or to failure with progressive overload marked by an increase in weight or repetitions to push participants to improve each session. As expected, given its type and design, this training protocol, which was focused on strength with no aerobic component, resulted in significant increases in strength but no significant increase in the absolute VO

2max or VO

2max adjusted for FFM. The obvious explanation for this result relates to the non-aerobic type of training, but this may also stem from the small sample size, as the absolute VO

2max seemed to increase by 11% after week 12 (post-bulk) and remained elevated by +8% after week 24 (post-cutting phase). Power calculations using the effect size (

pη

2=0.23) derived from this pilot study indicate that a sample size of 11 was required. However, the impact of our intervention on VO

2max was reduced when accounting for FFM (

pη

2=0.07). This outcome is expected considering that FFM increased as a result of the resistance training type of intervention (as discussed below) and the established connection between FFM and VO

2max[

18] . The dietary protocol was also closely monitored with weekly checks done at each training session to ensure participants were recording their meals.

If participants fell behind or missed days, we encouraged them to take pictures of all meals and log their food as accurately as possible when they had free time. This constant monitoring and supervision were significant strengths of this pilot intervention.

4.2. Improvements in Body Composition and Strength

Compared to current literature, which has looked at strictly resistance training or aerobic training and hypocaloric diets, our study showed greater improvements in strength and body composition with only 2 training sessions per week (compared to 3 sessions per week)[

19,

20]. One probable reason for these differences is the consistent monitoring of the training by the personal trainer and researchers who were always present to ensure exercises were performed correctly and close to maximum/failure, thus, leading to high compliance. In previous studies, compliance was often self-reported by the participants, and it is unknown whether subjects trained safely and effectively. Moreover,

even if compliance in previous studies matched that of the present study, it suggests that resistance training twice per week may be as effective as three times per week for untrained individuals. Another possible explanation is that our bulking and cutting diet was more conducive to improvements in body composition and strength, although further research is needed to confirm this assumption.

Although the effects of the dietary bulk and cut alone on body composition and strength are unknown, we observed a favourable change in body composition with our combined training and dietary intervention. A major concern for most of the participants was that they may lose strength while eating a hypocaloric diet, yet our resistance training program successfully resulted in increasing strength from the end of the bulking phase to the end of the cutting phase in two of the four exercises. We attribute this outcome to an increase in lean mass following the bulking phase (week 12), which was then sustained after the cutting phase (week 24). Moreover, following the bulking phase, there was a significant increase in body mass, which was expected as participants were instructed to consume more calories. After the subsequent cutting phase, body mass returned to baseline levels, though not without a favourable shift in body composition. That is, by week 24, body mass was similar to baseline levels, yet there was a significant increase in FFM and a notable decrease in body fat percentage. Since obesity is more accurately defined by adiposity rather than BMI, we view this result to be important since obesity, or higher levels of adiposity, is associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease [

21], type 2 diabetes [

22], several types of cancer [

23], low-grade inflammation [

24] and early mortality [

25]. Furthermore, obesity also decreases physical ability and quality of life [

26]; thus, an intervention that lowers fat mass without compromising muscle strength can significantly impact the lives of those living with obesity.

4.3. No Changes in Circulating Lipids

There were no significant changes in triglycerides and cholesterol levels. Previous studies using comparable resistance training protocols alone have demonstrated significant reductions in triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels [

27,

28,

29,

30]. One potential reason for the lipids remaining the same in the current study could be from the diets adapted by participants. Many were inclined towards eating a diet high in carbs and saturated fats to reach caloric goals during the bulking phase. This style of eating can lead to an increase in circulating cholesterol and triglycerides [

31,

32]. Moreover, the limited studies incorporating time-restricted eating or low-calorie diets alongside resistance training have reported conflicting findings on lipid profile improvements [

33,

34,

35]. As a result, the approach to eating and training in the current study may not be the most effective for improving lipid levels.

4.4. Changes in Resting Concentrations of Inflammatory Markers

Given that CRP levels exceeding 2.0 mg/L are considered a risk-enhancing factor for cardiovascular disease, the CRP concentrations of our male participants with obesity can be classified as slightly elevated [

36]. Importantly, CRP did not significantly change across the 24-week intervention. This finding agrees with previous studies using resistance training alone 3 times per week for 9 and 16 weeks in a comparable population, which also reported similar resting CRP concentrations and no training-induced changes[

37,

38]. Regarding exercise and diet, current research shows aerobic and high intensity interval training (HIIT) paired with caloric restriction were the most effective at reducing elevated levels of CRP [

39,

40,

41]. In these studies, participants exhibited higher baseline CRP levels, while groups engaging in HIIT and aerobic training without caloric restriction showed inconsistent CRP results.

Regarding the cytokine concentrations, the most notable change was the reduction in TNF-α which by the end of the 24-weeks, and after the cutting cycle reached significance. In addition, IL-6 concentrations, although not significant, decreased post-bulk and then returned near its baseline levels post-cut. Previous studies have also reported decreases in the circulating concentrations of major pro-inflammatory cytokines during timed-restricted eating and hypocaloric diets in endurance and resistance-trained individuals [

42,

43]. However, other studies using intermittent fasting on healthy males have found no significant changes [

44]. Increased adipose tissue has also been directly correlated with higher levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α [

45,

46,

47]. This makes it challenging to determine whether the decrease in TNF-α in the current study was due directly to either the loss of fat by our participants, the dietary changes, or the consistent resistance training. However, the significant decrease of circulating TNF-α is an indication of reduced inflammation, which is consistent with the loss of fat and an important factor for individuals with obesity.

In contrast, we observed no significant changes in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. The current literature presents mixed findings on the effects of exercise training on circulating IL-10 levels. For instance, a decrease in resting IL-10 concentrations was noted in frail older women after a resistance training program [

48]. Conversely, a meta-analysis on aerobic, resistance, and combined training in patients with metabolic syndrome reported increases in IL-6 and IL-10 levels following the combined regimen [

49]. In cancer patients, exercise training did not significantly affect IL-10 levels [

50]. Additionally, a large 12-month randomized controlled trial found no impact of aerobic exercise training on circulating IL-10 concentrations in post-menopausal women [

51]. This suggests that the relationship between exercise, diet and IL-10 remains unclear and may vary based on individual factors and training regimens.

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

This was a pilot study, and therefore, it was limited by its small sample size and the absence of a control group. The small sample size cannot be representative of the general population. The absence of a control group that would follow the bulk-and-cut dietary protocol without resistance training makes it challenging to isolate the effects of the intervention. Another limitation was regarding strategies participants used to hit target calories. While we encouraged participants to maintain usual eating habits, many adopted new strategies for both the bulking and the cutting cycles. Some gravitated towards a Western-styled diet to consume higher calories while others took this as an opportunity to prepare healthier meals, characterized by lean protein, unsaturated fats and whole grains. Then, for the cutting phase, when calories had dropped substantially, some participants would fast until the evening while others ate smaller meals throughout the day. This variability was not necessarily a limitation but because of the small sample size it limits generalizability of these findings. Nevertheless, results from the current pilot show substantial improvements in body composition and strength even with the inclusion of western-style food items.

This pilot study has some notable strengths. First, to date, this novel combination of resistance training with the specific bulk and cut dietary protocol, has only been practiced by professional body builders to quickly gain fat-free mass and lose body mass, and the current findings show promise in obese men as well. Second, regarding feasibility, feedback from the participants was all positive. Although some admitted the difficulty and discipline it required to follow the program for 24 weeks, the majority mentioned they enjoyed the experience. Last, the significant changes in body composition and retention/increase in strength demonstrates that this program can be a viable protocol for overweight or obese individuals.

5. Conclusions

The results of this pilot study showed that this novel 24-week resistance training intervention combined with a dietary bulk-and-cut protocol is feasible and can lead to moderate improvements in body composition and pro-inflammatory cytokines but not in lipid profiles in overweight or obese adult males. Specifically, fat-free mass increased, and body fat percentage decreased without compromising muscle strength, which also significantly improved with the training. Inflammatory changes were characterized by an overall decrease in TNF-α from baseline to the end of this 24-week pilot intervention. Since obesity is associated with low-grade inflammation [

24] and higher risk of chronic disease [

21,

22], including cancer [

23] and early mortality [

25], any intervention that can decrease the resting concentrations of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, and lower fat mass without compromising muscle strength is a significant contribution to the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.D., V.A.F. and P.K.; methodology, A.G., S.K., D.D., V.A.F. and P.K.; formal analysis, A.G., S.K. and P.K.; investigation, A.G., S.K., B.A. and J.M.C.; resources, B.A., V.A.F. and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, A.G., S.K., J.M.C.; D.D, V.A.F. and P.K.; supervision, P.K.; project administration, P.K.; funding acquisition, P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), grant number 2023-03572 to P.K.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brock University (protocol code HREB-22-135, 1/3/2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author PK upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants for their commitment and effort throughout the entirety of the study. A special appreciation goes to the personal trainer, whose expertise, guidance, and dedication were instrumental in ensuring the success of the exercise sessions. We also acknowledge the authors and researchers who contributed their time and effort to data collection and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RT |

Resistance Training |

| HIIT |

High Intensity Interval Training |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin-10 |

| TNF-α |

Tumour Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| LDL |

Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| HDL |

High-Density Lipoprotein |

| 1RM |

1 Repetition Maximum |

| AMDR |

Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges |

| FFM |

Fat-Free Mass |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

References

- Stubbs, C.O.; Lee, A.J. The Obesity Epidemic: Both Energy Intake and Physical Activity Contribute. Medical Journal of Australia 2004, 181, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westcott, W.L. Resistance Training Is Medicine: Effects of Strength Training on Health. Curr Sports Med Rep 2012, 11, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winett, R.A.; Carpinelli, R.N. Potential Health-Related Benefits of Resistance Training. Prev Med 2001, 33, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: The Evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigenbaum, M.S.; Pollock, M.L. Prescription of Resistance Training for Health and Disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999, 31, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Rissanen, J.; Pedwell, H.; Clifford, J.; Shragge, P. Influence of Diet and Exercise on Skeletal Muscle and Visceral Adipose Tissue in Men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1996, 81, 2445–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C.J.; Ozemek, C.; Carbone, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circ Res 2019, 124, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Resources. Available online: https://www.acsm.org/education-resources/trending-topics-resources/physical-activity-guidelines (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- BLOCK, G.; HARTMAN, A.M.; DRESSER, C.M.; CARROLL, M.D.; GANNON, J.; GARDNER, L. A DATA-BASED APPROACH TO DIET QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN AND TESTING. American Journal of Epidemiology 1986, 124, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeSuer, Dale A., et al. ‘The Accuracy of Prediction Equations for Estimating 1-RM Performance in the Bench Press, Squat, and Deadlift’. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, 1997, p. 211.

- Calorie Calculator. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/weight-loss/in-depth/calorie-calculator/itt-20402304 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Canada, H. Dietary Reference Intakes Tables: Reference Values for Macronutrients. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/dietary-reference-intakes/tables/reference-values-macronutrients.html (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Meyer, T.E.; Kovács, S.J.; Ehsani, A.A.; Klein, S.; Holloszy, J.O.; Fontana, L. Long-Term Caloric Restriction Ameliorates the Decline in Diastolic Function in Humans. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2006, 47, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, S.; Wei, X.; Zhang, P.; Guo, D.; Lin, J.; Xu, B.; Li, C.; et al. Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaveni, P.; Gowda, V.M. Assessing the Validity of Friedewald’s Formula and Anandraja’s Formula For Serum LDL-Cholesterol Calculation. J Clin Diagn Res 2015, 9, BC01–04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences; New York, 1988; ISBN 964-7445-88-1.

- Ekelund, U.; Franks, P.W.; Wareham, N.J.; Aman, J. Oxygen Uptakes Adjusted for Body Composition in Normal-Weight and Obese Adolescents. Obes Res 2004, 12, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Long, J.; Dan, S.; Johannsen, N.M.; Talamoa, R.; Raghuram, S.; Chung, S.; Kent, K.; Basina, M.; Lamendola, C.; et al. Strength Training Is More Effective than Aerobic Exercise for Improving Glycaemic Control and Body Composition in People with Normal-Weight Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreijen, A.M.; Engberink, M.F.; Memelink, R.G.; Plas, S.E. van der; Visser, M.; Weijs, P.J.M. Effect of a High Protein Diet and/or Resistance Exercise on the Preservation of Fat Free Mass during Weight Loss in Overweight and Obese Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrition Journal 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanthan, P.; Horwich, T.B.; Tseng, C.H. Relation of Muscle Mass and Fat Mass to Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. Am J Cardiol 2016, 117, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ambrosi, J.; Silva, C.; Galofré, J.C.; Escalada, J.; Santos, S.; Gil, M.J.; Valentí, V.; Rotellar, F.; Ramírez, B.; Salvador, J.; et al. Body Adiposity and Type 2 Diabetes: Increased Risk with a High Body Fat Percentage Even Having a Normal BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisling, H.; Arnold, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; O’Doherty, M.G.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Bamia, C.; Kampman, E.; Leitzmann, M.; Romieu, I.; Kee, F.; et al. Comparison of General Obesity and Measures of Body Fat Distribution in Older Adults in Relation to Cancer Risk: Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data of Seven Prospective Cohorts in Europe. Br J Cancer 2017, 116, 1486–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus 14, e22711. [CrossRef]

- Bigaard, J.; Frederiksen, K.; Tjønneland, A.; Thomsen, B.L.; Overvad, K.; Heitmann, B.L.; Sørensen, T.I.A. Body Fat and Fat-Free Mass and All-Cause Mortality. Obes Res 2004, 12, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.B. The Effect of Obesity on Health Outcomes. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2010, 316, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banz, W.J.; Maher, M.A.; Thompson, W.G.; Bassett, D.R.; Moore, W.; Ashraf, M.; Keefer, D.J.; Zemel, M.B. Effects of Resistance versus Aerobic Training on Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003, 228, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, A.L.; Marcus, B.H.; Kampert, J.B.; Garcia, M.E.; Kohl, H.W.; Blair, S.N. Reduction in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: 6-Month Results from ProjectActive. Preventive Medicine 1997, 26, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donovan, G.; Owen, A.; Bird, S.R.; Kearney, E.M.; Nevill, A.M.; Jones, D.W.; Woolf-May, K. Changes in Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factors Following 24 Wk of Moderate- or High-Intensity Exercise of Equal Energy Cost. Journal of Applied Physiology 2005, 98, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami Vatani, D.; Ahmadi, S.; Ahmadi Dehrashid, K.; Gharibi, F. Changes in Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Inflammatory Markers of Young, Healthy, Men after Six Weeks of Moderate or High Intensity Resistance Training. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2011, 51, 695–700. [Google Scholar]

- Laufs, U.; Parhofer, K.G.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Hegele, R.A. Clinical Review on Triglycerides. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 99–109c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.A.S.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Appel, L.J.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Meyer, K.A.; Petersen, K.; Polonsky, T.; Van Horn, L. ; On behalf of the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; and Stroke Council Dietary Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Risk: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e39–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotarsky, C.J.; Johnson, N.R.; Mahoney, S.J.; Mitchell, S.L.; Schimek, R.L.; Stastny, S.N.; Hackney, K.J. Time-Restricted Eating and Concurrent Exercise Training Reduces Fat Mass and Increases Lean Mass in Overweight and Obese Adults. Physiological Reports 2021, 9, e14868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirelles, C.M.; Gomes, P.S.C. Combined Effects of Resistance Training and Carbohydrate-Restrictive or Conventional Diets on Weight Loss, Blood Variables and Endothelium Function. Rev. Nutr. 2016, 29, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REZAEIPOUR, M.; APANASENKO, G.; NYCHYPORUK, V. Investigating the Effects of Negative-Calorie Diet Compared with Low-Calorie Diet under Exercise Conditions on Weight Loss and Lipid Profile in Overweight/Obese Middle-Aged and Older Men. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences 2014, 44, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 74, e177–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, N.F.; Rogers, E.M.; Stanhewicz, A.E.; Whitaker, K.M.; Jenkins, N.D.M. Resistance Exercise Lowers Blood Pressure and Improves Vascular Endothelial Function in Individuals with Elevated Blood Pressure or Stage-1 Hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2024, 326, H256–H269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcellos, F.C.; Del Vecchio, F.B.; Reges, A.; Mielke, G.; Santos, I.S.; Umpierre, D.; Bohlke, M.; Hallal, P.C. Exercise in Patients with Hypertension and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Hum Hypertens 2018, 32, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reljic, D.; Dieterich, W.; Herrmann, H.J.; Neurath, M.F.; Zopf, Y. “HIIT the Inflammation”: Comparative Effects of Low-Volume Interval Training and Resistance Exercises on Inflammatory Indices in Obese Metabolic Syndrome Patients Undergoing Caloric Restriction. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.-Y.N.; Hong, S.; Wilson, K.L.; Calfas, K.J.; Rock, C.L.; Redwine, L.S.; von Känel, R.; Mills, P.J. Effects of Caloric Intake and Aerobic Activity in Individuals with Prehypertension and Hypertension on Levels of Inflammatory, Adhesion and Prothrombotic Biomarkers-Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei Bahmanbeglou, N.; Ebrahim, K.; Maleki, M.; Nikpajouh, A.; Ahmadizad, S. Short-Duration High-Intensity Interval Exercise Training Is More Effective Than Long Duration for Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness But Not for Inflammatory Markers and Lipid Profiles in Patients With Stage 1 Hypertension. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention 2019, 39, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Bianco, A.; Marcolin, G.; Pacelli, Q.F.; Battaglia, G.; Palma, A.; Gentil, P.; Neri, M.; Paoli, A. Effects of Eight Weeks of Time-Restricted Feeding (16/8) on Basal Metabolism, Maximal Strength, Body Composition, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Resistance-Trained Males. Journal of Translational Medicine 2016, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Longo, G.; Grigoletto, D.; Bianco, A.; Ferraris, C.; Guglielmetti, M.; Veneto, A.; Tagliabue, A.; Marcolin, G.; et al. Time-Restricted Eating Effects on Performance, Immune Function, and Body Composition in Elite Cyclists: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2020, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halberg, N.; Henriksen, M.; Söderhamn, N.; Stallknecht, B.; Ploug, T.; Schjerling, P.; Dela, F. Effect of Intermittent Fasting and Refeeding on Insulin Action in Healthy Men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2005, 99, 2128–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Parameswaran, V.; Udayan, R.; Burgess, J.; Jones, G. Circulating Levels of Inflammatory Markers Predict Change in Bone Mineral Density and Resorption in Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2008, 93, 1952–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.M.; Freitas, E.D.S.; Heishman, A.D.; Peak, K.M.; Buchanan, S.R.; Bemben, D.A.; Bemben, M.G. Associations of Serum IL-6 with Muscle, Bone, and Adipose Tissue in Women. Cytokine 2022, 151, 155787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, L.; Pitrone, M.; Guarnotta, V.; Giordano, C.; Pizzolanti, G. Irisin: A Possible Marker of Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eustáquio, F.G.; Uba, C.M.; Guerra, M.L.; Luis, R.; Carlos, C.J.; Eef, H.; Pedro, F.J.; Maria, T.A. The Mediating Effect of Different Exercise Programs on the Immune Profile of Frail Older Women with Cognitive Impairment. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2020, 26, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizaei Yousefabadi, H.; Niyazi, A.; Alaee, S.; Fathi, M.; Mohammad Rahimi, G.R. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Exercise on Metabolic Syndrome Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol Res Nurs 2021, 23, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosravi, N.; Stoner, L.; Farajivafa, V.; Hanson, E.D. Exercise Training, Circulating Cytokine Levels and Immune Function in Cancer Survivors: A Meta-Analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2019, 81, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, S.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Brenner, D.R.; Shaw, E.; O’Reilly, R.; Yasui, Y.; Woolcott, C.G.; Friedenreich, C.M. Impact of Aerobic Exercise on Levels of IL-4 and IL-10: Results from Two Randomized Intervention Trials. Cancer Med 2016, 5, 2385–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).