Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

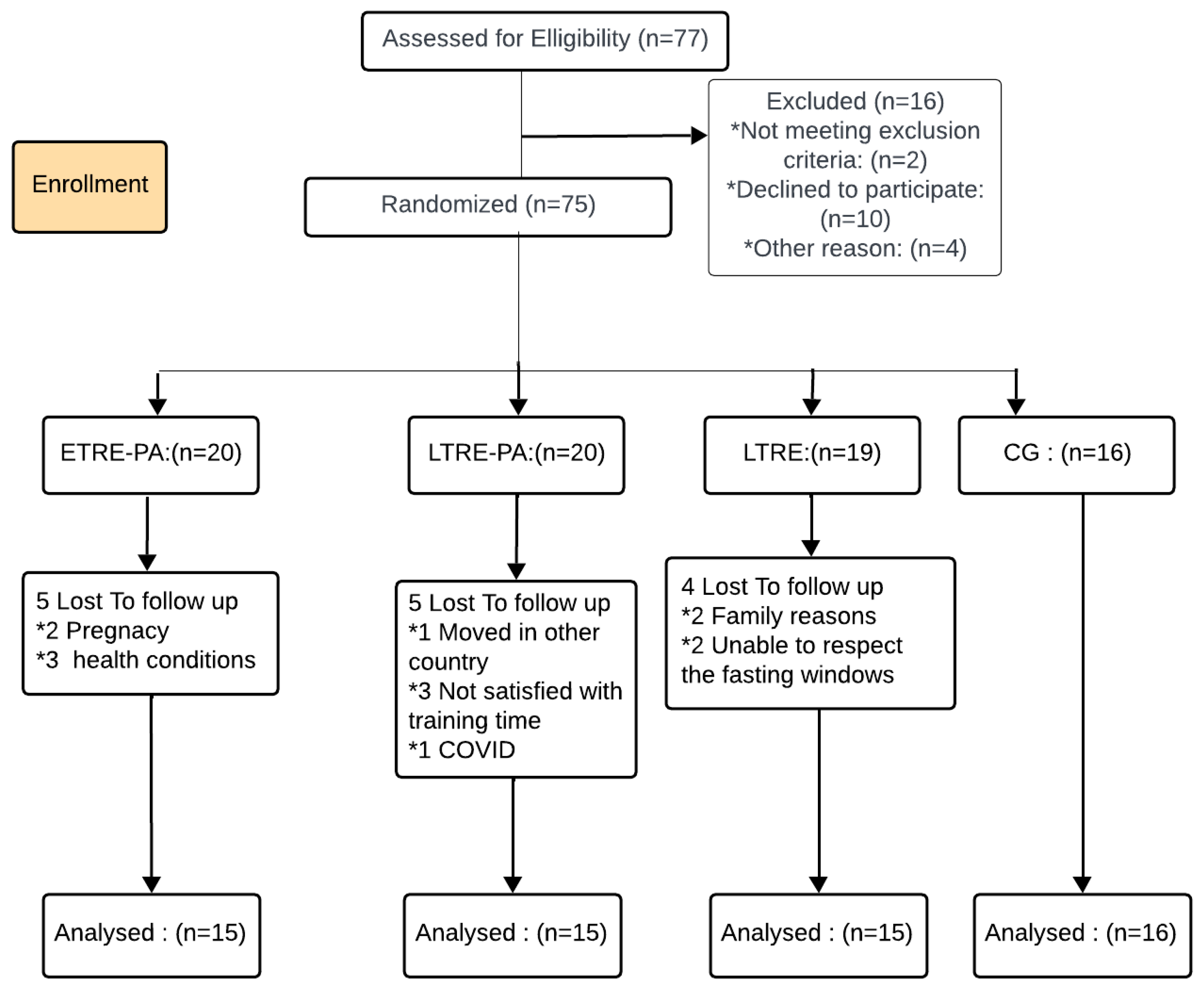

2.1. Participants

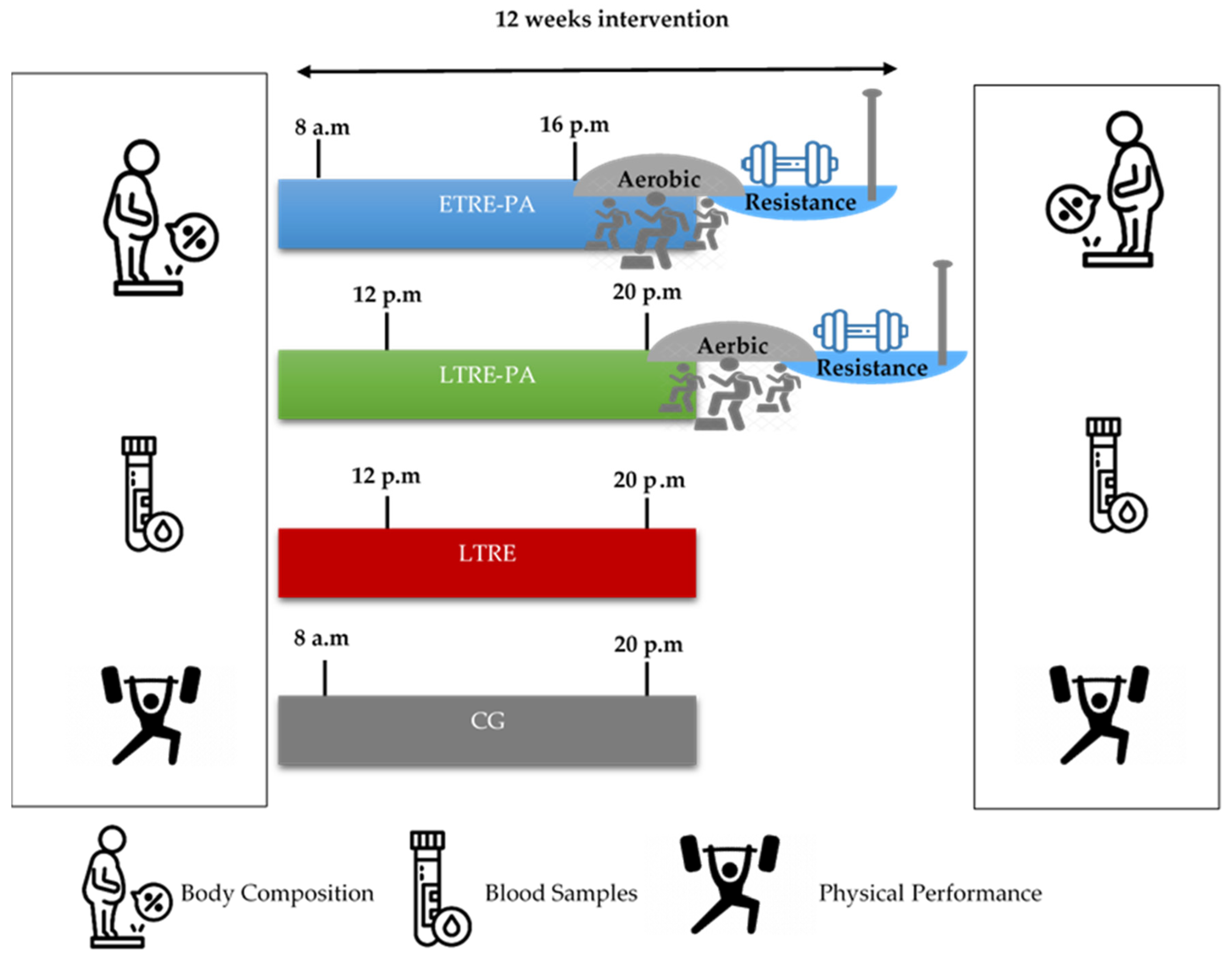

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Training Sessions

2.3.1. Endurance Training

2.3.2. Strength Training

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Blood Samples

2.6. Functional Capacity

2.6.1. Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT)

2.6.2. Strength Tests

2.6.3. Vertical Jump Test

2.6.4. 30 s Crunch and Squat Test

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Body Composition

4.2. Metabolic Parameters

4.3.2. LE and BP 1-RM

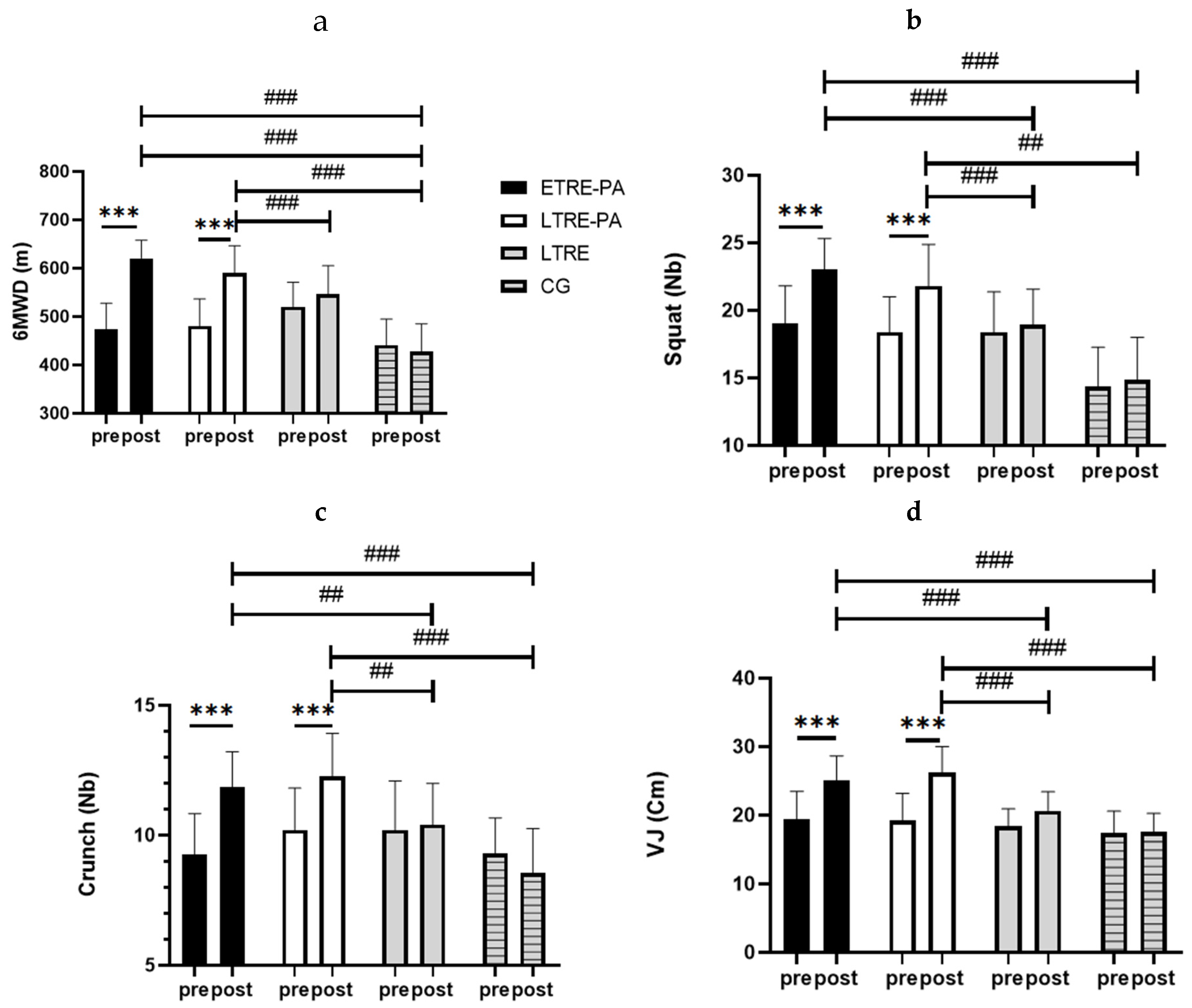

4.3.3. Explosiveness and Endurance Strength

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Okunogbe, A.; Nugent, R.; Spencer, G.; Powis, J.; Ralston, J.; Wilding, J. Economic Impacts of Overweight and Obesity: Current and Future Estimates for 161 Countries. BMJ Glob Health 2022, 7, e009773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, C. M.; Carroll, M. D.; Fryar, C. D.; Ogden, C. L. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017-2018. NCHS Data Brief 2020, 360, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, D.; Su, X.; Gao, Z. Health Wearable Devices for Weight and BMI Reduction in Individuals with Overweight/Obesity and Chronic Comorbidities: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2021, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J. D.; Buscemi, J.; Milsom, V.; Malcolm, R.; O’Neil, P. M. Effects on Cardiovascular Risk Factors of Weight Losses Limited to 5-10. Transl Behav Med 2016, 6, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Y. Optimal Diet Strategies for Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance. J Obes Metab Syndr 2021, 30, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesani, A.; Barkhidarian, B.; Jafarzadeh, M.; Akbarzade, Z.; Djafarian, K.; Shab-Bidar, S. Time-Related Meal Patterns and Breakfast Quality in a Sample of Iranian Adults. BMC Nutrition 2023, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, H.; Beyl, R. A.; Della Manna, D. L.; Yang, E. S.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C. M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Affects Markers of the Circadian Clock, Aging, and Autophagy in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, E1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R. A. D.; Szmuchrowski, L. A.; Rosa, J. P. P.; Santos, M. A. P. dos; de Mello, M. T.; Savoi, L.; Porto, Y. F.; de Assis Dias Martins Júnior, F.; Drummond, M. D. M. Intermittent Fasting Promotes Weight Loss without Decreasing Performance in Taekwondo. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D. L.; Hawley, N. A.; Mohr, A. E.; Hermer, J.; Ofori, E.; Yu, F.; Sears, D. D. Impact of Intermittent Fasting and/or Caloric Restriction on Aging-Related Outcomes in Adults: A Scoping Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Bao, L.; Yang, P.; Zhou, H. Health Effects of the Time-Restricted Eating in Adults with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1079250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E. A.; Zaman, A.; Sloggett, K. J.; Steinke, S.; Grau, L.; Catenacci, V. A.; Cornier, M.-A.; Rynders, C. A. Early Time-Restricted Eating Compared with Daily Caloric Restriction: A Randomized Trial in Adults with Obesity. Obesity 2022, 30, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ye, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, H.; He, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Randomized Controlled Trial for Time-Restricted Eating in Healthy Volunteers without Obesity. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchison, A. T.; Regmi, P.; Manoogian, E. N. C.; Fleischer, J. G.; Wittert, G. A.; Panda, S.; Heilbronn, L. K. Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Glucose Tolerance in Men at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019, 27, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazeminasab, F.; Baharlooie, M.; Karimi, B.; Mokhtari, K.; Rosenkranz, S. K.; Santos, H. O. Effects of Intermittent Fasting Combined with Physical Exercise on Cardiometabolic Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Nutrition Reviews 2023, nuad155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albosta, M.; Bakke, J. Intermittent Fasting: Is There a Role in the Treatment of Diabetes? A Review of the Literature and Guide for Primary Care Physicians. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol 2021, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R. F. L.; Muñoz, V. R.; Junqueira, R. L.; de Oliveira, F.; Gaspar, R. C.; Nakandakari, S. C. B. R.; Costa, S. de O.; Torsoni, M. A.; da Silva, A. S. R.; Cintra, D. E.; de Moura, L. P.; Ropelle, E. R.; Zaghloul, I.; Mekary, R. A.; Pauli, J. R. Time-Restricted Feeding Combined with Aerobic Exercise Training Can Prevent Weight Gain and Improve Metabolic Disorders in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. The Journal of Physiology 2022, 600, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petridi, F.; Geurts, J. M. W.; Nyakayiru, J.; Schaafsma, A.; Schaafsma, D.; Meex, R. C. R.; Singh-Povel, C. M. Effects of Early and Late Time-Restricted Feeding on Parameters of Metabolic Health: An Explorative Literature Assessment. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boege, H. L.; Bhatti, M. Z.; St-Onge, M.-P. Circadian Rhythms and Meal Timing: Impact on Energy Balance and Body Weight. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2021, 70, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.; Grau, L.; Jeffers, R.; Steinke, S.; Catenacci, V. A.; Cornier, M.-A.; Rynders, C. A.; Thomas, E. A. The Effects of Early Time Restricted Eating plus Daily Caloric Restriction Compared to Daily Caloric Restriction Alone on Continuous Glucose Levels. Obesity Science & Practice 2023, 10, e702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaloul, R.; Ben Dhia, I.; Marzougui, H.; Turki, M.; Kacem, F. H.; Makhlouf, R.; Amar, M. B.; Kallel, C.; Driss, T.; Elleuch, M. H.; Ayadi, F.; Ghroubi, S.; Hammouda, O. Is Moderate-Intensity Interval Training More Tolerable than High-Intensity Interval Training in Adults with Obesity? Biol Sport 2023, 40, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. A.; Deasy, W.; Stathis, C. G.; Hayes, A.; Cooke, M. B. Intermittent Fasting with or without Exercise Prevents Weight Gain and Improves Lipids in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, E346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, T. W. The Importance of a Priori Sample Size Estimation in Strength and Conditioning Research. J Strength Cond Res 2013, 27, 2323–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miladi, S.; Hammouda, O.; Ameur, R.; Miladi, S. C.; Feki, W.; Driss, T. Time-Restricted Eating Benefits on Pulmonary Function and Postural Balance in Overweight or Obese Women. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunani, A.; Perna, S.; Soranna, D.; Rondanelli, M.; Zambon, A.; Bertoli, S.; Vinci, C.; Capodaglio, P.; Lukaski, H.; Cancello, R. Body Composition Assessment Using Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) in a Wide Cohort of Patients Affected with Mild to Severe Obesity. Clinical Nutrition 2021, 40, 3973–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beqa Ahmeti, G.; Idrizovic, K.; Elezi, A.; Zenic, N.; Ostojic, L. Endurance Training vs. Circuit Resistance Training: Effects on Lipid Profile and Anthropometric/Body Composition Status in Healthy Young Adult Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W. T.; Levy, R. I.; Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, without Use of the Preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, S. A. F.; Faintuch, J.; Fabris, S. M.; Nampo, F. K.; Luz, C.; Fabio, T. L.; Sitta, I. S.; de Batista Fonseca, I. C. Six-Minute Walk Test: Functional Capacity of Severely Obese before and after Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009, 5, 540–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.; Seelhorst, D.; Snyder, S. Comparison of Metabolic and Heart Rate Responses to Super Slow Vs. Traditional Resistance Training. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association 2003, 17, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarilla, C. T.; Sautter, N. M.; Robinson, Z. P.; Juber, M. C.; Hickmott, L. M.; Cerminaro, R. M.; Benitez, B.; Carzoli, J. P.; Bazyler, C. D.; Zoeller, R. F.; Whitehurst, M.; Zourdos, M. C. Accuracy of Predicting One-Repetition Maximum from Submaximal Velocity in The Barbell Back Squat and Bench Press. J Hum Kinet 2022, 82, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crose, A.; Alvear, A.; Singroy, S.; Wang, Q.; Manoogian, E.; Panda, S.; Mashek, D. G.; Chow, L. S. Time-Restricted Eating Improves Quality of Life Measures in Overweight Humans. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Song, Y. Early Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight and Improves Glycemic Response in Young Adults: A Pre-Post Single-Arm Intervention Study. Obes Facts 2022, 16, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragon, A. A.; Schoenfeld, B. J. Does Timing Matter? A Narrative Review of Intermittent Fasting Variants and Their Effects on Bodyweight and Body Composition. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yi, P.; Liu, F. The Effect of Early Time-Restricted Eating vs Later Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Metabolic Health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023, 108, 1824–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, J. do N.; Macedo, R. C. O.; Dos Santos, G. C.; Munhoz, S. V.; Machado, C. L. F.; de Menezes, R. L.; Menzem, E. N.; Moritz, C. E. J.; Pinto, R. S.; Tinsley, G. M.; de Oliveira, A. R. Cardiometabolic Effects of Early v. Delayed Time-Restricted Eating plus Energetic Restriction in Adults with Overweight and Obesity: An Exploratory Randomised Clinical Trial. Br J Nutr. [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, H.; Steger, F.; Bryan, D.; Richman, J.; Warriner, A.; Hanick, C.; Martin, C.; Salvy, S.-J.; Peterson, C. Effectiveness of Early Time-Restricted Eating for Weight Loss, Fat Loss, and Cardiometabolic Health in Adults With Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 2022, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C.; Yang, S.; Wei, X.; Zhang, P.; Guo, D.; Lin, J.; Xu, B.; Li, C.; He, H.; He, J.; Liu, S.; Shi, L.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, H. Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss. New England Journal of Medicine 2022, 386, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, R.; Watanabe, D.; Ito, K.; Ueda, K.; Nakayama, K.; Sanbongi, C.; Miyachi, M. Dose–Response Relationship between Protein Intake and Muscle Mass Increase: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrition Reviews 2021, 79, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. A.; Zhu, S.; List, E. O.; Duran-Ortiz, S.; Slama, Y.; Berryman, D. E. Musculoskeletal Effects of Altered GH Action. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakupova, E. I.; Bocharnikov, A. D.; Plotnikov, E. Y. Effects of Ketogenic Diet on Muscle Metabolism in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D. A.; Wu, N.; Rohdin-Bibby, L.; Moore, A. H.; Kelly, N.; Liu, Y. E.; Philip, E.; Vittinghoff, E.; Heymsfield, S. B.; Olgin, J. E.; Shepherd, J. A.; Weiss, E. J. Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men With Overweight and Obesity: The TREAT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2020, 180, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R. E.; Laughlin, G. A.; Sears, D. D.; LaCroix, A. Z.; Marinac, C.; Gallo, L. C.; Hartman, S. J.; Natarajan, L.; Senger, C. M.; Martínez, M. E.; Villaseñor, A. INTERMITTENT FASTING AND HUMAN METABOLIC HEALTH. J Acad Nutr Diet 2015, 115, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotarsky, C. J.; Johnson, N. R.; Mahoney, S. J.; Mitchell, S. L.; Schimek, R. L.; Stastny, S. N.; Hackney, K. J. Time-Restricted Eating and Concurrent Exercise Training Reduces Fat Mass and Increases Lean Mass in Overweight and Obese Adults. Physiological Reports 2021, 9, e14868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, P.; O’Connor, S. G.; Heckman-Stoddard, B. M.; Sauter, E. R. Time-Restricted Feeding Studies and Possible Human Benefit. JNCI Cancer Spectr 2022, 6, pkac032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasim, I.; Majeed, C. N.; DeBoer, M. D. Intermittent Fasting and Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.; Mottillo, E. P. Adipocyte Lipolysis: From Molecular Mechanisms of Regulation to Disease and Therapeutics. Biochem J 2020, 477, 985–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Williams, K. J.; Verlande-Ferrero, A.; Chan, A. P.; Su, G. B.; Kershaw, E. E.; Cox, J. E.; Maschek, J. A.; Shapira, S. N.; Christofk, H. R.; Vallim, T. Q. de A.; Masri, S.; Villanueva, C. J. Acute Activation of Adipocyte Lipolysis Reveals Dynamic Lipid Remodeling of the Hepatic Lipidome. Journal of Lipid Research 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirinzi, V.; Poli, C.; Berteotti, C.; Leone, A. Browning of Adipocytes: A Potential Therapeutic Approach to Obesity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taetzsch, A.; Roberts, S. B.; Bukhari, A.; Lichtenstein, A. H.; Gilhooly, C. H.; Martin, E.; Krauss, A. J.; Hatch-McChesney, A.; Das, S. K. Eating Timing: Associations with Dietary Intake and Metabolic Health. J Acad Nutr Diet 2021, 121, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, G.; Souza, M.; Pereira, L. Relationship between Omitting Breakfast and Late Eating with Obesity and Metabolic Disorders: A Review Focusing on Chrononutrition. Archives of Health 2023, 4, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoo, J. L.; Shapiro, S. A.; Bradsell, H.; Frank, R. M. The Essential Roles of Human Adipose Tissue: Metabolic, Thermoregulatory, Cellular, and Paracrine Effects. Journal of Cartilage & Joint Preservation 2021, 1, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R. L.; Yadav, P. K.; Yadav, L. K.; Agrawal, K.; Sah, S. K.; Islam, M. N. Association between Obesity and Heart Rate Variability Indices: An Intuition toward Cardiac Autonomic Alteration—a Risk of CVD. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2017, 10, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucidi, P.; Perriello, G.; Porcellati, F.; Pampanelli, S.; Fano, M.; Tura, A.; Bolli, G.; Fanelli, C. Diurnal Cycling of Insulin Sensitivity in Type 2 Diabetes: Evidence for Deviation From Physiology at an Early Stage. Diabetes 2023, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, P.; Oster, H.; Korf, H. W.; Foster, R. G.; Erren, T. C. Food as a Circadian Time Cue—Evidence from Human Studies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2020, 16, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Wan, K.; Miyashita, M.; Ho, R. S.; Zheng, C.; Poon, E. T.; Wong, S. H. The Effect of Time-Restricted Eating Combined with Exercise on Body Composition and Metabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in Nutrition 2024, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real-Hohn, A.; Navegantes, C.; Ramos, K.; Ramos-Filho, D.; Cahuê, F.; Galina, A.; Salerno, V. P. The Synergism of High-Intensity Intermittent Exercise and Every-Other-Day Intermittent Fasting Regimen on Energy Metabolism Adaptations Includes Hexokinase Activity and Mitochondrial Efficiency. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0202784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Brandhorst, S.; Shelehchi, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Cheng, C. W.; Budniak, J.; Groshen, S.; Mack, W. J.; Guen, E.; Di Biase, S.; Cohen, P.; Morgan, T. E.; Dorff, T.; Hong, K.; Michalsen, A.; Laviano, A.; Longo, V. D. Fasting-Mimicking Diet and Markers/Risk Factors for Aging, Diabetes, Cancer, and Cardiovascular Disease. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9, eaai8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Bianco, A.; Marcolin, G.; Pacelli, Q. F.; Battaglia, G.; Palma, A.; Gentil, P.; Neri, M.; Paoli, A. Effects of Eight Weeks of Time-Restricted Feeding (16/8) on Basal Metabolism, Maximal Strength, Body Composition, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Resistance-Trained Males. Journal of Translational Medicine 2016, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, G. M.; Moore, M. L.; Graybeal, A. J.; Paoli, A.; Kim, Y.; Gonzales, J. U.; Harry, J. R.; VanDusseldorp, T. A.; Kennedy, D. N.; Cruz, M. R. Time-Restricted Feeding plus Resistance Training in Active Females: A Randomized Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2019, 110, 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaïdia, A.-E.; Daab, W.; Bouzid, M. A. Effects of Ramadan Fasting on Physical Performance: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med 2020, 50, 1009–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J. M.; Santos, I.; Pezarat-Correia, P.; Silva, A. M.; Mendonca, G. V. Effects of Ramadan and Non-Ramadan Intermittent Fasting on Body Composition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Nutr 2020, 7, 625240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J. M.; Santos, P. D. G.; Pezarat-Correia, P.; Minderico, C. S.; Infante, J.; Mendonca, G. V. Effect of Time-Restricted Eating and Resistance Training on High-Speed Strength and Body Composition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Montilla, J. J.; Cuevas-Cervera, M.; Gonzalez-Muñoz, A.; Garcia-Rios, M. C.; Navarro-Ledesma, S. Efficacy of Nutritional Strategies on the Improvement of the Performance and Health of the Athlete: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Longo, G.; Grigoletto, D.; Bianco, A.; Ferraris, C.; Guglielmetti, M.; Veneto, A.; Tagliabue, A.; Marcolin, G.; Paoli, A. Time-Restricted Eating Effects on Performance, Immune Function, and Body Composition in Elite Cyclists: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2020, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aird, T. P.; Farquharson, A. J.; Bermingham, K. M.; O’Sulllivan, A.; Drew, J. E.; Carson, B. P. Divergent Serum Metabolomic, Skeletal Muscle Signaling, Transcriptomic, and Performance Adaptations to Fasted versus Whey Protein-Fed Sprint Interval Training. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2021, 321, E802–E820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, A. J.; Langton, H. M.; Mulligan, M.; Egan, B. Effects of 8 Wk of 16:8 Time-Restricted Eating in Male Middle- and Long-Distance Runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2021, 53, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Ratamess, N. A.; Faigenbaum, A. D.; Bush, J. A.; Beller, N.; Vargas, A.; Fardman, B.; Andriopoulos, T. Effect of Time-Restricted Feeding on Anthropometric, Metabolic, and Fitness Parameters: A Systematic Review. J Am Nutr Assoc 2022, 41, 810–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, A. P.; Richardson, C. E.; Keim, N. L.; Van Loan, M. D.; Davis, B. A.; Casazza, G. A. Four Weeks of 16/8 Time Restrictive Feeding in Endurance Trained Male Runners Decreases Fat Mass, without Affecting Exercise Performance. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, G. M.; Forsse, J. S.; Butler, N. K.; Paoli, A.; Bane, A. A.; La Bounty, P. M.; Morgan, G. B.; Grandjean, P. W. Time-Restricted Feeding in Young Men Performing Resistance Training: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur J Sport Sci 2017, 17, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J. M.; Santos, I.; Pezarat-Correia, P.; Minderico, C.; Schoenfeld, B. J.; Mendonca, G. V. Effects of Time-Restricted Feeding on Supramaximal Exercise Performance and Body Composition: A Randomized and Counterbalanced Crossover Study in Healthy Men. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouhal, H.; Bagheri, R.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Wong, A.; Triki, R.; Hackney, A. C.; Laher, I.; Abderrahman, A. B. Effects of Ramadan Intermittent Fasting on Inflammatory and Biochemical Biomarkers in Males with Obesity. Physiology & Behavior 2020, 225, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarkers | ETRE-PA | LTRE-PA | LTRE | CG | ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | F(1, 57) | P (Time) |

ηp² (Time) | |

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.75±0.76 | 2.32**±0.54 | 2.65±0.76 | 2.46±0.95 | 2.38±0.72 | 2.12±0.54 | 3.17±1.08 | 2.39±0.63 | 24.27 | 0.000 | 0.29 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.47±0.90 | 3.76***±0.64 | 4.29±0.96 | 3.98.96±1.38 | 4.13±0.91 | 3.69**±0.69 | 4.96±1.24 | 3.87±0.85 | 43.07 | 0.000 | 0.43 |

| ALAT (UI/L) | 14.73±10 | 6.38**±2.14 | 13.60 ±7.28 | 7.04* ±3.34 | 12.66 ±10.8 | 7.80±2.27 | 19.07±15.66 | 11.31±7.69 | 24.97 | 0.000 | 0.30 |

| ASAT (UI/L) | 18.13±6.45 | 12.53 ±2.16 | 20.20 ±14.10 | 12.60*±5.69 | 19.86±10.09 | 15.33±8.98 | 21.31±15.41 | 15.68±7.94 | 12.85 | 0.001 | 0.18 |

| Phosphatase Alcalin (UI/L) | 77.06±34.77 | 79.6±21.56 | 61.60±13.08 | 56.93±16.69 | 79.60±21.56 | 72.00±20.72 | 59.37±14.54 | 45.37±15.51 | 5.62 | 0.02 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).