Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Physical fitness and diet along with body weight are key determinants of health. Excess body weight, poor dietary choices, and low physical fitness, however, are becoming increasingly prevalent in adolescents. In order to develop adequate intervention strategies additional research on potential interaction effects of these entities is needed. Therefore, this study examined the combined association of physical fitness and diet with body weight in Austrian adolescents. Methods: A total of 164 (56% male) adolescents between 11 and 14 years of age completed the German Motor Test, which consists of 8 items that assess cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular endurance and power, speed and agility, flexibility and balance, along with body weight and height measurements. Additionally, participants completed a standardized food frequency questionnaire. Results: Spearman correlation analyses showed an inverse association between physical fitness and processed foods consumption (rho = -0.25, p<0.01), while sweet consumption was positively associated with physical fitness (rho = 0.17, p=0.03). No significant interaction effects between diet and physical fitness on body weight were observed. However, both higher physical fitness and greater sweet consumption were associated with lower body weight (p<0.01). Conclusions: The present study emphasizes the independent and combined interactions of key correlates of health. It also suggests that high fitness may offset detrimental effects of poor dietary choices. In order to address potential health risks early in life and facilitate future health and well-being, it is important to monitor and control physical fitness, diet and body weight during adolescence.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Factor 1 (processed foods): frozen & fast food, energy drink, alcohol (Eigenvalue=4.12; explains 24.23% of variance)

- Factor 2 (plant-based diet): fruits, nuts, soy milk (Eigenvalue=2.01; explains 11.84% of variance)

- Factor 3 (healthy mixed diet): rice, bread/noodles, fish, vegetables, water (Eigenvalue=1.49; explains 8.75% of variance)

- Factor 4 (animal-based diet): meat, eggs, milk (Eigenvalue=1.14; explains 6.72% of variance)

- Factor 5 (sweets): sweets, jam (Eigenvalue=1.08; explains 6.37% of variance)

- Factor 6 (supplements): dietary supplements (Eigenvalue=1.04; explains 6.11% of variance)

3. Results

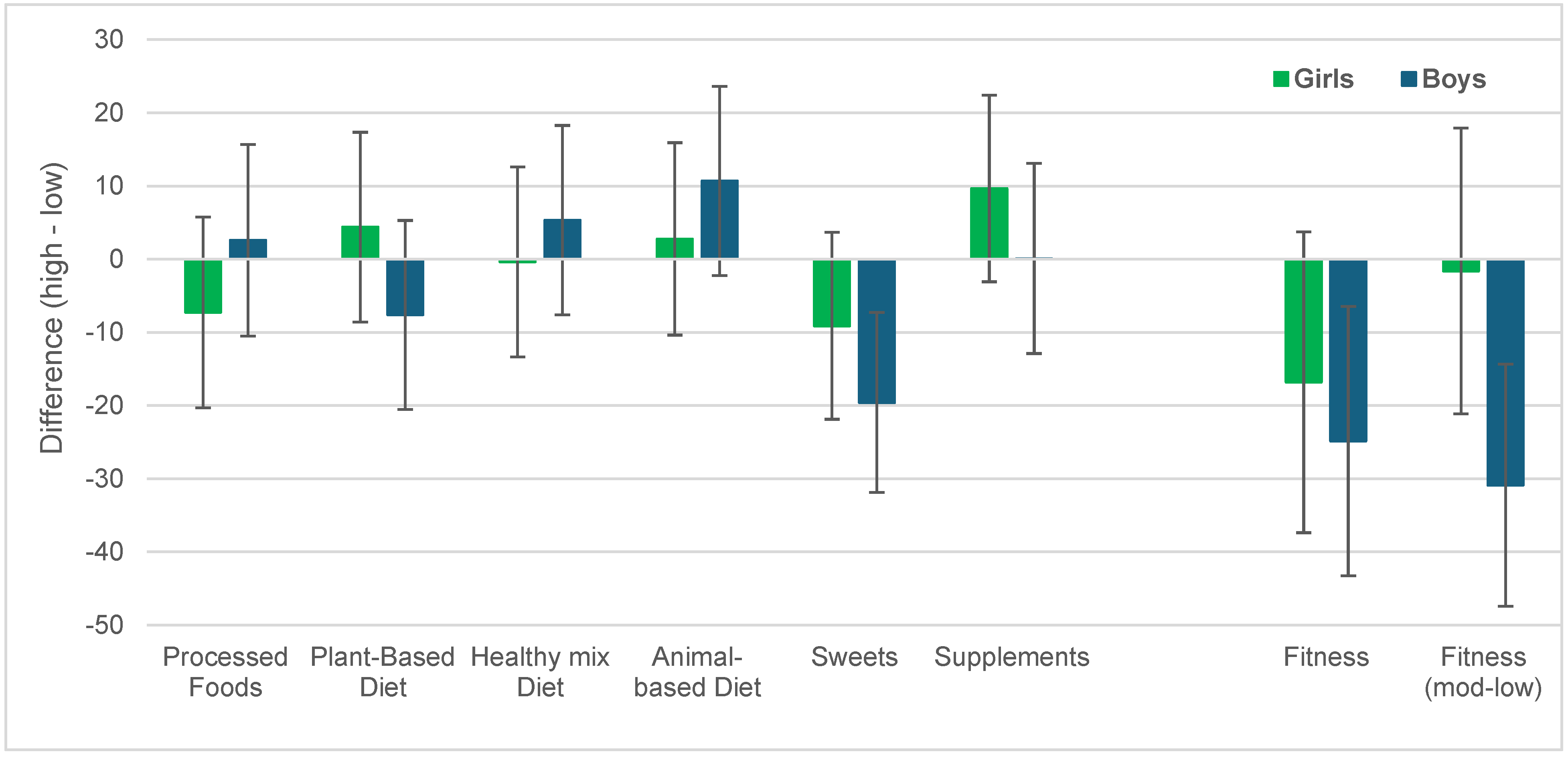

3.1. Diet Factors and Physical Fitness

3.2. Association of Dietary Factors and Physical Fitness with Body Weight

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Candari CJ, Cylus J, Nolte E. Assessing the economic costs of unhealthy diets and low physical activity: An evidence review and proposed framework. Copenhagen, Denmark. 2017.

- Balagopal PB, de Ferranti SD, Cook S, Daniels SR, Gidding SS, Hayman LL, et al. Nontraditional risk factors and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease: mechanistic, research, and clinical considerations for youth: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011, 123(23), 2749-69.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403(10431), 1027-50. [CrossRef]

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384(9945), 766-81.

- Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016, 17(2), 95-107. [CrossRef]

- Apovian, CM. Obesity: definition, comorbidities, causes, and burden. Am J Manag Care 2016, 22(7 Suppl), s176–85. [Google Scholar]

- Finer, N. Medical consequences of obesity. Medicine 2014, 43(2), 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieker EA, Pyzocha N. Economic Impact of Obesity. Prim Care 2016, 43(1), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390(10113), 2627-42.

- Wang ZH, Zou ZY, Dong YH, Xu RB, Yang YD, Ma J. A Healthy Lifestyle Offsets the Increased Risk of Childhood Obesity Caused by High Birth Weight: Results From a Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 736900. [CrossRef]

- Grigorakis DA, Georgoulis M, Psarra G, Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Sidossis LS. Prevalence and lifestyle determinants of central obesity in children. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55(5), 1923-31. [CrossRef]

- Popkin BM, Duffey K, Gordon-Larsen P. Environmental influences on food choice, physical activity and energy balance. Physiol Behav 2005, 86(5), 603-13. [CrossRef]

- Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011, 5(12), CD001871. [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden L, Jones J, Williams CM, Finch M, Wyse RJ, Kingsland M, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 10(10), CD011779. [CrossRef]

- Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, Sjöström M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes (Lond), 2008, 32(1), 1-11.

- Evaristo S, Moreira C, Lopes L, Oliveira A, Abreu S, Agostinis-Sobrinho C, et al. Muscular fitness and cardiorespiratory fitness are associated with health-related quality of life: Results from labmed physical activity study. J Exerc Sci Fit 2019, 17(2), 55-61. [CrossRef]

- Högström G, Nordström A, Eriksson M, Nordström P. Risk factors assessed in adolescence and the later risk of stroke in men: a 33-year follow-up study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2015, 39(1), 63-71. [CrossRef]

- Högström G, Nordström A, Nordström P. High aerobic fitness in late adolescence is associated with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction later in life: a nationwide cohort study in men. Eur Heart J 2014, 35(44), 3133-40. [CrossRef]

- Harber MP, Peterman JE, Imboden M, Kaminsky L, Ashton REM, Arena R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a vital sign of CVD risk in the COVID-19 era. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2023, 76, 44-8. [CrossRef]

- Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, Church TS, Després JP, Franklin BA, et al. Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 134(24), e653-e99. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos P, Faselis C, Samuel IBH, Pittaras A, Doumas M, Murphy R, et al. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality Risk Across the Spectra of Age, Race, and Sex. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 80(6), 598-609. [CrossRef]

- Myers J, McAuley P, Lavie CJ, Despres JP, Arena R, Kokkinos P. Physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness as major markers of cardiovascular risk: their independent and interwoven importance to health status. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2015, 57(4), 306-14. [CrossRef]

- López-Gil JF, Martínez-López MF. Clustering of Dietary Patterns Associated with Health-Related Quality of Life in Spanish Children and Adolescents. Nutrients. 2024, 16(14), 2308. [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem L, Román-Viñas B, Sanchez-Villegas A, Guasch-Ferré M, Corella D, La Vecchia C. Benefits of the Mediterranean diet: Epidemiological and molecular aspects. Mol Aspects Med 2019, 67, 1-55. [CrossRef]

- Yu X, Zou Z. Dietary, Lifestyle, and Children Health. Nutrients 2023, 15(10), 2242.

- Rosi A, Paolella G, Biasini B, Scazzina F, SINU Working Group on Nutritional Surveillance in Adolescents. Dietary habits of adolescents living in North America, Europe or Oceania: A review on fruit, vegetable and legume consumption, sodium intake, and adherence to the Mediterranean Diet. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2019, 29(6), 544-60.

- Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020, 4(1), 23-35.

- Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay MS. Temporal trends in the cardiorespiratory fitness of children and adolescents representing 19 high-income and upper middle-income countries between 1981 and 2014. Br J Sports Med 2019, 53(8), 478-86. [CrossRef]

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh AC, et al. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet 2012, 379(9826), 1630-40. [CrossRef]

- Craigie AM, Lake AA, Kelly SA, Adamson AJ, Mathers JC. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70(3), 266-84. [CrossRef]

- Lake AA, Mathers JC, Rugg-Gunn AJ, Adamson AJ. Longitudinal change in food habits between adolescence (11-12 years) and adulthood (32-33 years): the ASH30 Study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2006, 28(1), 10-6. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilä V, Räsänen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr 2005, 93(6), 923-31.

- García-Hermoso A, Izquierdo M, Ramírez-Vélez R. Tracking of physical fitness levels from childhood and adolescence to adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Pediatr 2022, 11(4), 474-86. [CrossRef]

- Twig G, Yaniv G, Levine H, Leiba A, Goldberger N, Derazne E, et al. Body-Mass Index in 2.3 Million Adolescents and Cardiovascular Death in Adulthood. N Engl J Med 2016, 374(25), 2430-40. [CrossRef]

- Loef M, Walach H. The combined effects of healthy lifestyle behaviors on all cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2012, 55(3), 163-70. [CrossRef]

- de Mello GT, Minatto G, Costa RM, Leech RM, Cao Y, Lee RE, et al. Clusters of 24-hour movement behavior and diet and their relationship with health indicators among youth: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24(1), 1080. [CrossRef]

- Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Wabitsch M, Kunze D, Geller F, Geiß H, Hesse V, et al. Perzentile für den Body-mass-Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2001, 49, 807-18. [CrossRef]

- Bös K, Schlenker L, Büsch D, Lämmle L, Müller H, Oberger J, et al. Deutscher Motorik-Test 6-18 (DMT6-18) [German motor abilities test 6-18 (DMT6-18)]. Hamburg, Germany: Czwalina; 2009.

- Ruiz JR, Castro-Piñero J, Artero EG, Ortega FB, Sjöström M, Suni J, et al. Predictive validity of health-related fitness in youth: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2009, 43(12), 909-23.

- Greier K, Ruedl G, Weber C, Thöni G, Riechelmann H. Ernährungsverhalten und motorische Leistungsfähigkeit von 10- bis 14-jährigen Jugendlichen. E & M - Ernährung und Medizin 2016, 31, 166-71.

- Mishra P, Pandey CM, Singh U, Gupta A, Sahu C, Keshri A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann Card Anaesth 2019, 22(1), 67-72. [CrossRef]

- Galan-Lopez P, Ries F, Gisladottir T, Domínguez R, Sánchez-Oliver AJ. Healthy Lifestyle: Relationship between Mediterranean Diet, Body Composition and Physical Fitness in 13 to 16-Years Old Icelandic Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15(12), 2632. [CrossRef]

- Galan-Lopez P, Sánchez-Oliver AJ, Ries F, González-Jurado JA. Mediterranean Diet, Physical Fitness and Body Composition in Sevillian Adolescents: A Healthy Lifestyle. Nutrients 2019, 11(9), 2009. [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Carrasco S, Felipe JL, Sanchez-Sanchez J, Hernandez-Martin A, Clavel I, Gallardo L, et al. Relationship between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Body Composition with Physical Fitness Parameters in a Young Active Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(9), 3337. [CrossRef]

- Muros JJ, Cofre-Bolados C, Arriscado D, Zurita F, Knox E. Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with lifestyle, physical fitness, and mental wellness among 10-y-olds in Chile. Nutrition 2017, 35, 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Carrasco S, Felipe JL, Sanchez-Sanchez J, Hernandez-Martin A, Gallardo L, Garcia-Unanue J. Weight Status, Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, and Physical Fitness in Spanish Children and Adolescents: The Active Health Study. Nutrients 2020, 12(6), 1680. [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino Idelson P, Scalfi L, Valerio G. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2017, 27(4), 283-99. [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Serrano M, López-Gil JF, Sevil-Serrano J, García-Hermoso A, Sánchez-Miguel PA. What is the role of adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines in relation to physical fitness components among adolescents? Scand J Med Sci Sports 2023, 33(8), 1373-83.

- Tigerstrand Grevnerts H, Delisle Nyström C, Migueles JH, Löf M. Longitudinal associations of meeting the WHO physical activity guidelines and physical fitness, from preschool to childhood. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2024, 34(4), e14624. [CrossRef]

- Eslami O, Zarei M, Shidfar F. The association of dietary patterns and cardiorespiratory fitness: A systematic review. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2020, 30(9), 1442-51. [CrossRef]

- Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Psarra G, Sidossis LS. Association of cardiorespiratory fitness levels with dietary habits and lifestyle factors in schoolchildren. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2019, 44(5), 539-45. [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Valls MR, Adelantado-Renau M, Moliner-Urdiales D. Reallocating time spent in physical activity intensities: Longitudinal associations with physical fitness (DADOS study). J Sci Med Sport 2020, 23(10), 968-72. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz JR, Rizzo NS, Hurtig-Wennlöf A, Ortega FB, Wärnberg J, Sjöström M. Relations of total physical activity and intensity to fitness and fatness in children: the European Youth Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2006, 84(2), 299-303. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier AC, Guimarães RF, Namiranian K, Drapeau V, Mathieu ME. Effect of Physical Exercise on Taste Perceptions: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2020, 12(9), 2741. [CrossRef]

- Larson N, DeWolfe J, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Adolescent consumption of sports and energy drinks: linkages to higher physical activity, unhealthy beverage patterns, cigarette smoking, and screen media use. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014, 46(3), 181-7. [CrossRef]

- Ranjit N, Evans MH, Byrd-Williams C, Evans AE, Hoelscher DM. Dietary and activity correlates of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents. Pediatrics 2010, 126(4), e754-61. [CrossRef]

- Lahoz-García N, García-Hermoso A, Milla-Tobarra M, Díez-Fernández A, Soriano-Cano A, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Cardiorespiratory Fitness as a Mediator of the Influence of Diet on Obesity in Children. Nutrients 2018, 10(3), 358. [CrossRef]

- Abbasalizad Farhangi M, Mohammadi Tofigh A, Jahangiri L, Nikniaz Z, Nikniaz L. Sugar-sweetened beverages intake and the risk of obesity in children: An updated systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Pediatr Obes 2022, 17(8), e12914. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen DD, Brader L, Bruun JM. Association between Food, Beverages and Overweight/Obesity in Children and Adolescents-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2023, 15(3), 764. [CrossRef]

- Wilkie HJ, Standage M, Gillison FB, Cumming SP, Katzmarzyk PT. Multiple lifestyle behaviours and overweight and obesity among children aged 9-11 years: results from the UK site of the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment. BMJ Open 2016, 6(2), e010677. [CrossRef]

- Zandvakili I, Pulaski M, Pickett-Blakely O. A phenotypic approach to obesity treatment. Nutr Clin Pract 2023, 38(5), 959-75. [CrossRef]

- Carpena Lucas PJ, Sánchez-Cubo F, Vargas Vargas M, Mondéjar Jiménez J. Influence of Lifestyle Habits in the Development of Obesity during Adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(7), 4124. [CrossRef]

- Diehl K, Yarmoliuk T, Mayer J, Zipfel S, Schnell A, Thiel A, et al. Eating patterns of elite adolescent athletes: Results of a cross-sectional study of 51 Olympic sports. Dtsch Z Sportmed 2013, 64, 126-31. [CrossRef]

- Larson N, Story M. A review of snacking patterns among children and adolescents: what are the implications of snacking for weight status? Child Obes 2013, 9(2), 104-15. [CrossRef]

- Rauner A, Mess F, Woll A. The relationship between physical activity, physical fitness and overweight in adolescents: a systematic review of studies published in or after 2000. BMC Pediatr 2013, 13, 19. [CrossRef]

- Joensuu L, Tammelin TH, Syväoja HJ, Barker AR, Parkkari J, Kujala UM. Physical activity, physical fitness and self-rated health: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations in adolescents. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2024, 10(1), e001642. [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Moledo C, Fernández-Santos JD, Izquierdo-Gómez R, Esteban-Cornejo I, Rio-Cozar P, Carbonell-Baeza A, et al. Physical Fitness and Self-Rated Health in Children and Adolescents: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(7), 2413. [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola T, Yli-Piipari S, Huotari P, Watt A, Liukkonen J. Fundamental movement skills and physical fitness as predictors of physical activity: A 6-year follow-up study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016, 26(1), 74-81. [CrossRef]

- Glenmark B, Hedberg G, Jansson E. Prediction of physical activity level in adulthood by physical characteristics, physical performance and physical activity in adolescence: an 11-year follow-up study. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1994, 69(6), 530-8. [CrossRef]

- Silva G, Andersen LB, Aires L, Mota J, Oliveira J, Ribeiro JC. Associations between sports participation, levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in childrenand adolescents. J Sports Sci 2013, 31(12), 1359-67. [CrossRef]

- Hui SS, Zhang R, Suzuki K, Naito H, Balasekaran G, Song JK, et al. Physical activity and health-related fitness in Asian adolescents: The Asia-fit study. J Sports Sci 2020, 38(3), 273-9. [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos P, Faselis C, Samuel IBH, Lavie CJ, Zhang J, Vargas JD, et al. Changes in Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Survival in Patients With or Without Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81(12), 1137-47. [CrossRef]

- Liberali R, Del Castanhel F, Kupek E, Assis M. Latent Class Analysis of Lifestyle Risk Factors and Association with Overweight and/or Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review. Child Obes 2021, 17(1), 2-15. [CrossRef]

- Pereira L, Hinnig P, Matsuo L, Di Pietro P, de Assis M, Vieira F. Association between lifestyle patterns and overweight and obesity in adolescents: a systematic review. Br J Nutr 2023, 129(9), 1626-44. [CrossRef]

| Total Sample (N = 164) |

Girls (N = 73) |

Boys (N = 91) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) ** | 12.9 ± 1.2 | 12.7 ± 1.1 | 13.1 ± 1.2 |

| Height (cm) ** | 161.3 ± 8.9 | 158.7 ± 6.7 | 163.4 ± 9.9 |

| Body weight (kg) * | 53.8 ± 14.4 | 51.3 ± 10.0 | 55.9 ± 16.9 |

| BMI Percentile | 59.6 ± 29.4 | 61.3 ± 27.5 | 58.2 ± 31.0 |

| 6 Min Run (Z) | 94.1 ± 11.2 | 99.1 ± 8.6 | 90.2 ± 11.5 |

| Push Ups (Z) | 108.1 + 11.2 | 109.9 + 10.0 | 106.6 ± 11.9 |

| Sit Ups (Z) * | 95.2 ± 8.7 | 97.2 ± 6.9 | 93.6 ± 9.7 |

| Longjump (Z) | 103.3 ± 11.7 | 103.6 ± 10.6 | 102.9 ± 12.5 |

| Side Jumps (Z) | 113.7 ± 10.9 | 114.3 10.9 | 113.2 ± 10.9 |

| 20m Sprint (Z) * | 105.8 ± 12.4 | 103.3 ± 12.5 | 107.8 ± 12.1 |

| Balance (Z) | 105.2 ± 10.0 | 105.4 ± 8.4 | 105.0 ± 11.2 |

| Stand and Reach (Z) * | 99.9 ± 11.5 | 102.5 ± 10.8 | 97.9 ± 11.7 |

| Total Fitness (Z) | 103.3 ± 7.7 | 104.6 ± 7.0 | 102.3 ± 8.1 |

| Processed Foods | Plant-based Diet | Healthy mixed Diet | Animal-based Diet | Sweets | Supple-ments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | High | 57.1 % | 46.2 % | 47.3 % | 57.1 % | 50.5 % | 51.6 % |

| Low | 42.9 % | 53.8 % | 52.7 % | 42.9 % | 49.5 % | 48.4 % | |

| Girls | High | 41.1 % | 53.4 % | 53.4 % | 41.1 % | 49.3 % | 47.9 % |

| Low | 58.9 % | 46.6 % | 46.6 % | 58.9 % | 50.7 % | 48.4 % |

| 6 Min run | Push Ups | Sit Ups | Long Jump | Side Jumps | Sprint | Balance | Flexibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processed Foods | -0.33** | -0.24** | -0.17* | -0.11 | -0.25* | -0.03 | -0.16* | -0.04 |

| Animal-based diet | -0.14 | -0.12 | -0.17* | -0.02 | -0.06 | -0.12 | 0.04 | -0.07 |

| Plant-based diet | 0.18* | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Sweets | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.19** | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| High | Moderate | Low | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processed Foods | 58.5 ± 29.7 | N / A | 60.7 ± 29.3 | 0.63 |

| Plant-based Diet | 58.6 ± 28.8 | N / A | 60.6 ± 30.2 | 0.66 |

| Healthy mixed Diet | 61.1 ± 30.3 | N / A | 58.1 ± 28.7 | 0.52 |

| Animal-based Diet | 62.8 ± 27.9 | N / A | 56.3 ± 30.7 | 0.16 |

| Sweets | 52.1 ± 30.7 | N / A | 67.1 ± 26.2 | <0.01 |

| Supplements | 61.7 ± 30.6 | N / A | 57.5 ± 28.3 | 0.36 |

| Physical Fitness | 50.9 ± 25.5 | 54.7 ± 28.7 | 73.1 ± 29.3 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).