1. Introduction

Mining provides economic opportunities and income streams to several countries, thereby reducing poverty, especially in developing countries (Morley et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2018). However, the continued expansion of mining activities worldwide has profoundly affected the environment of rural communities, intensifying the tension between development discourse and ecosocial cohesion across affected communities (Annor et al., 2024; Hota and Behera, 2016; Oskarsson et al., 2024). Since mining activities mostly occur in rural areas, they are disproportionately affected by environmental degradation and suffer severe consequences (Brown et al., 2024). Mining activities lead to multifaceted environmental degradation, including deforestation, pollution, depletion of natural resources vital for rural communities to maintain their livelihoods (Hinojosa, 2013; Mactaggart et al., 2016), deterioration of environmental aesthetics, and threat to biodiversity (Gençay and Durkaya, 2023; Morley et al., 2022; Tiamgne et al., 2022).

Extractive industries, such as coal mining, permanently disrupt the local ecosystem, which can undermine local economic activities and the long-term sustainability of community livelihoods (Hota and Behera, 2016; Zhao and Niu, 2023). Direct mining effects, such as soil loss, impact the livelihoods of local people by causing a decrease or complete cessation of agricultural activities in rural areas (Oskarsson et al., 2024). This is because mining activities radically change the existing land cover, transforming it into an industry-oriented form of land use (Owen et al., 2024). Thus, in contexts where non-agricultural employment opportunities are limited (Twerefoo, 2021), mining weakens the livelihoods of rural households (Mtero, 2017) that largely depend on natural resource-based livelihoods.

Beyond environmental degradation, mining activities can forcibly or indirectly displace local communities, posing risks of unemployment, impoverishment, marginalization, and deprived access to traditional food sources (Manduna, 2023a), as well as a loss of social capital (Khan and Temocin, 2022; Mactaggart et al., 2016; Ofori et al., 2023). This displacement disproportionately affects rural communities, particularly those where strong bonds with land and established social networks are vital to well-being (Gukurume and Tombindo, 2023). However, research on these mining-induced ecosocial problems remains quite limited in the social work literature (Kvam and Willet, 2019). Investigating these issues—situated at the intersection of nature and human life—from a social work perspective is crucial for providing an evidence base for ecosocial practice at the micro (individuals and families), mezzo (groups and organizations), and macro (societal and structural) levels. Aiming to contribute to this evidence base across multiple levels of intervention, this study seeks to assess the processes of mining-induced environmental degradation and displacement from the perspectives of villagers directly affected in two rural communities in Turkey and to identify the resulting needs within the context of ecosocial work.

2. Conceptual Framework

A growing interest in ecological crises in recent years has effectively increased the visibility of the natural environment in the field of social work (Boetto et al., 2020; Gray and Coates, 2013; Parra Ramajo and Prat Bau, 2024; Powers et al., 2019). This area of focus, centered on ecological crises and sustainability, is often described using overlapping terms such as environmental social work, green social work, and ecosocial work—concepts that aim to place the natural environment at the core of social work practice (Boetto et al., 2020; Nöjd et al., 2024). This study adopts the term “ecosocial work” as it recognizes the intrinsic value of the natural environment and is shaped by a commitment to ecological justice (Boetto, 2017).

Environmental degradation and displacement from mining stem from unsustainable economic activities, which involve both social and ecological destruction. They are directly related to the principles of ecological justice, sustainability, and degrowth advocated by ecosocial work (Boetto, 2017). Ecosocial work aims to protect the sustainability and biodiversity of the ecosystem. It focuses on the inequalities arising from the unfair allocation of environmental resources and risks and advocates for an understanding of ecological justice for all living things (Boetto, 2025; Chang et al., 2025). Rooted in environmental activism, ecosocial work is based on the view that human beings are part of nature and environmental problems are structural and political issues (Närhi et al., 2025).

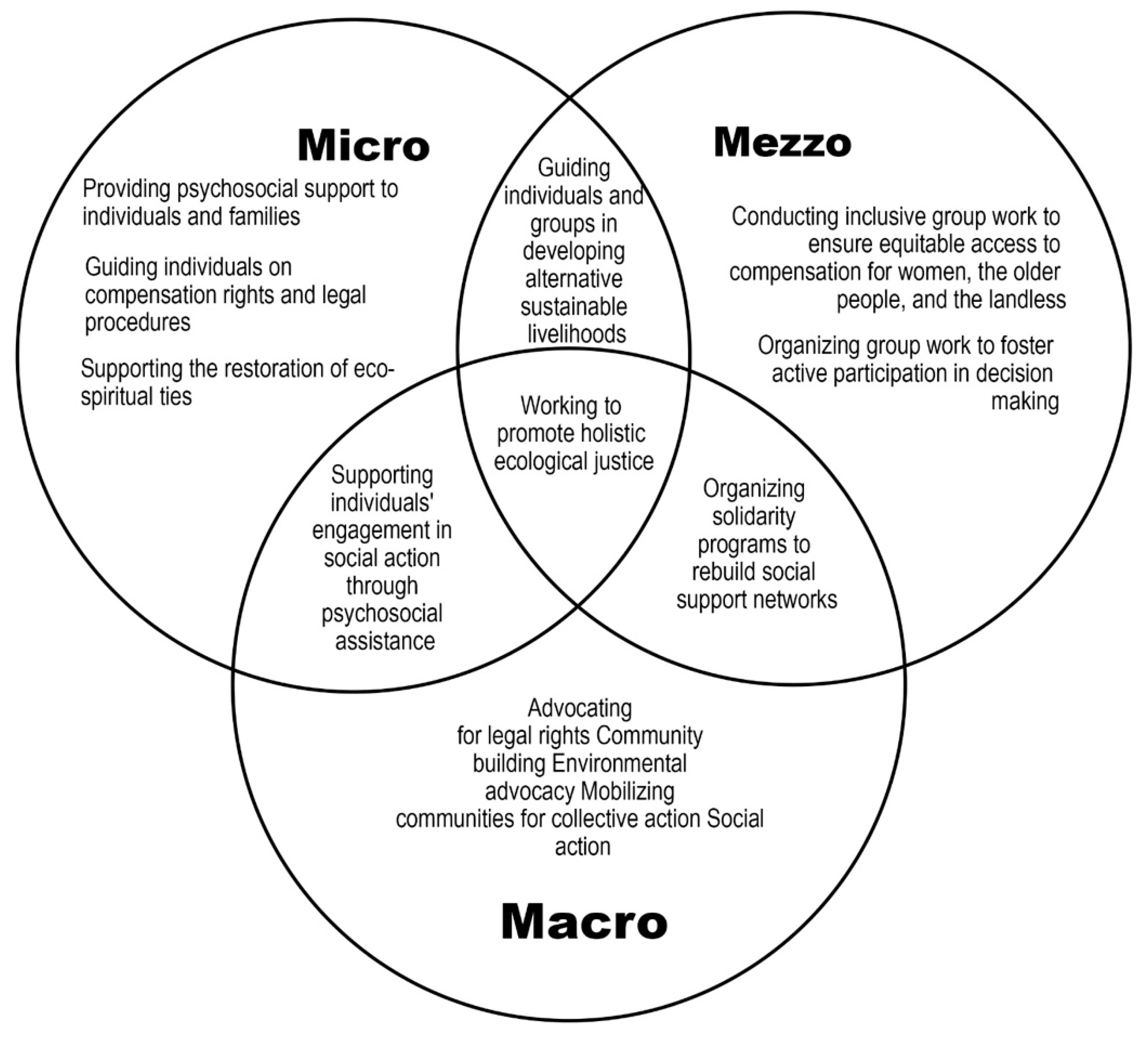

Social work bears an important responsibility toward the global economic structure that is beset by various social and ecological challenges (Matthies et al., 2020; Närhi and Matthies, 2016). Therefore, it must confront not only environmental unsustainability but also unsustainable economic structures; thus, beyond contributing to sustainability, it should include economic transformation in its agenda (Boetto et al., 2024; Matthies et al., 2020). In this context, ecosocial work collectively considers social, ecological, and economic sustainability, suggesting that growth-oriented models lead to inequality and environmental destruction (Närhi et al., 2025; Shackelford et al., 2024). It attempts to systematically understand problems ranging from local to global in a “glocal” context. This approach aims to understand the origins of phenomena that affect individuals and communities and their relationship with sustainability (Ranta-Tyrkkö et al., 2024). As a practice-based approach, ecosocial work involves interventions at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels (Boetto, 2017; Boetto, 2025). Although ecosocial work is a field of practice for social work rather than a theory (Wang and Altanbulag, 2022), there is a notable lack of practice-oriented intervention development (Boetto et al., 2020; Cashwell, 2024; Teixeira et al., 2019). Therefore, the current research aims to provide a knowledge base for micro-, mezzo-, and macro-level interventions within the ecosocial work framework in response to mining-related issues.

3. Literature Review

The increasing demand for minerals and supportive policies for the mining sector make developing countries attractive for mining investments (Hota and Behera, 2016). However, mining entails various risks for developing countries. The main risks include limited regulatory capacity, widespread corruption, and restricted access to justice for vulnerable communities affected by adverse impacts (Boone Barrera, 2019). On the other hand, legal regulations in developing countries are increasingly being expanded to promote mining activities (Jacka, 2018). In 1985, Turkey liberalized its extractive industries to meet the demands of a growing economy, allowing foreign companies to obtain mining licenses (Christensen and Christensen, 2024). Furthermore, with the comprehensive revision of Mining Law No. 3213 and Forest Law No. 6831, mining activities have been permitted even in the most valuable forested areas. As a result, mining has become one of the main causes of deforestation in Turkey (Atmiş et al., 2024; Elvan, 2013; Gençay and Durkaya, 2023; Günşen and Atmiş, 2018). This situation is associated with an inability to establish an appropriate balance between environmental protection and mining activities due to a dominant mining logic, the transfer of land and public spaces into the control of private companies, and a lack of transparency (Christensen and Christensen, 2024; Elvan, 2013). In addition to deforestation, mining activities are also among the leading causes of air, water, and soil degradation in Turkey (Arkoc et al., 2016; Tozsin and Öztaş, 2023).

Mining-related environmental degradation and the expansion of such activities can directly and indirectly lead to the displacement of communities. The spatial transformation process that begins with the establishment of a mining site results in the dispossession of the land’s previous owners and its former uses (Askland, 2018). Mining-induced displacement is characterized by the uncertainty created through the gradual expansion of projects over time, the continued residence of displaced people near mining sites, and the development of mutual dependencies between companies and communities (Owen and Kemp, 2015). This situation threatens housing and food security in mining communities, as well as the social support networks, livelihoods, and sustainability of affected populations (Huang et al., 2023; Manduna, 2023a; Ofori et al., 2023). On the other hand, mining-induced displacement is not unique to developing countries; it also occurs in developed nations. However, problems such as unemployment, food, and housing insecurity are not common consequences of mining-induced displacement in developed countries (Huang et al., 2023). Since there are no prior studies in the social work literature targeting individuals, families, and communities potentially affected before displacement actually occurs, this study can be considered the first significant initiative conducted from an ecosocial work perspective.

4. Research Setting

This study was conducted in two coal mining villages in the Manisa-Soma district in the Aegean Region of Turkey: Deniş and Eğnez. In Turkey, villages that depend on olive cultivation and are situated in areas with significant mineral reserves, such as Deniş and Eğnez, have long been losing their olive groves and natural habitats due to mining activities. Although both villages have a long history of mining, land losses due to mining have become especially evident since 1985. In the last decade, expropriation has accelerated, with residential areas being acquired by companies. Although the state has expropriation authority in Turkey, private mining companies pay the villagers directly for their land because they are the ones conducting the mining activities. In this process, since the consent of landowners is not required under Expropriation Law No. 2942, villagers lose their land for very low compensation and without being meaningfully involved in the process.

This study was conducted after the formal processes such as expropriation and transfer of ownership had been completed, but the actual eviction process had not yet begun. The state was in the process of resettling the villagers of Deniş and Eğnez. However, eligibility for these new settlements was subject to certain criteria, including income security. Consequently, some older people and women living alone in the villages did not meet the eligibility criteria. For the first time in their lives, they would be forced to leave their villages and pay rent for their premises. In both villages, only about half of the population was eligible for the new settlements. However, residences in the new settlement area were valued higher than the beneficiaries’ old homes and land in the villages. The new homes would thus require installment payments for nearly 20 years—a significant economic burden for the displaced villagers.

5. Method

5.1. Purpose and Research Questions

This qualitative case study aimed to assess mining-induced environmental degradation and displacement from the perspective of villagers and to identify the foundational requirements for ecosocial work interventions. To achieve these objectives, the following research questions were explored:

RQ1: How do villagers assess the impacts of mining-induced environmental degradation on the ecological system of their villages?

RQ2: How do villagers assess the impacts of mining-induced environmental degradation on their community?

RQ3: How do villagers assess the process of displacement caused by mining activities?

RQ4: How do villagers assess the resettlement practices in relation to the displacement process?

5.2. Participants

The purposive sample comprised 18 participants recruited using the maximum diversity method and reached through snowball sampling. The selection criteria required participants to be over 18 years of age and permanent residents of either of the two villages. Other participants were identified through the headmen of the two villages, who were designated as key informants. Seven participants were from Eğnez Village, and eleven were from Deniş Village. The sample comprised nine females and nine males. The participants’ ages ranged from 43 to 85 years.

5.3. Data Collection

Data were collected between March and November 2024 in two stages; first from Deniş Village and subsequently from Eğnez Village. The same procedures were followed in the data collection process in both villages. The research was conducted when villagers were preparing for displacement and resettlement. Although the evacuation had not yet officially begun, the villagers were preparing to relocate according to the official decision. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted face-to-face. The functionality of the interview questions was tested by conducting two pilot interviews and obtaining expert opinions. Before starting the interviews, the participants were informed about the purpose and scope of the research, stating that the interviews would be recorded, and participants’ written consent was obtained. Follow-up interviews were conducted to fill in the gaps identified in the first interviews, and each participant was interviewed at least twice to deepen the narratives. Code names such as P1, P2, and so on were assigned to the participants to protect their identities. The data collection process was terminated when information power was considered attained (Braun and Clarke, 2022).

5.4. Data Analysis

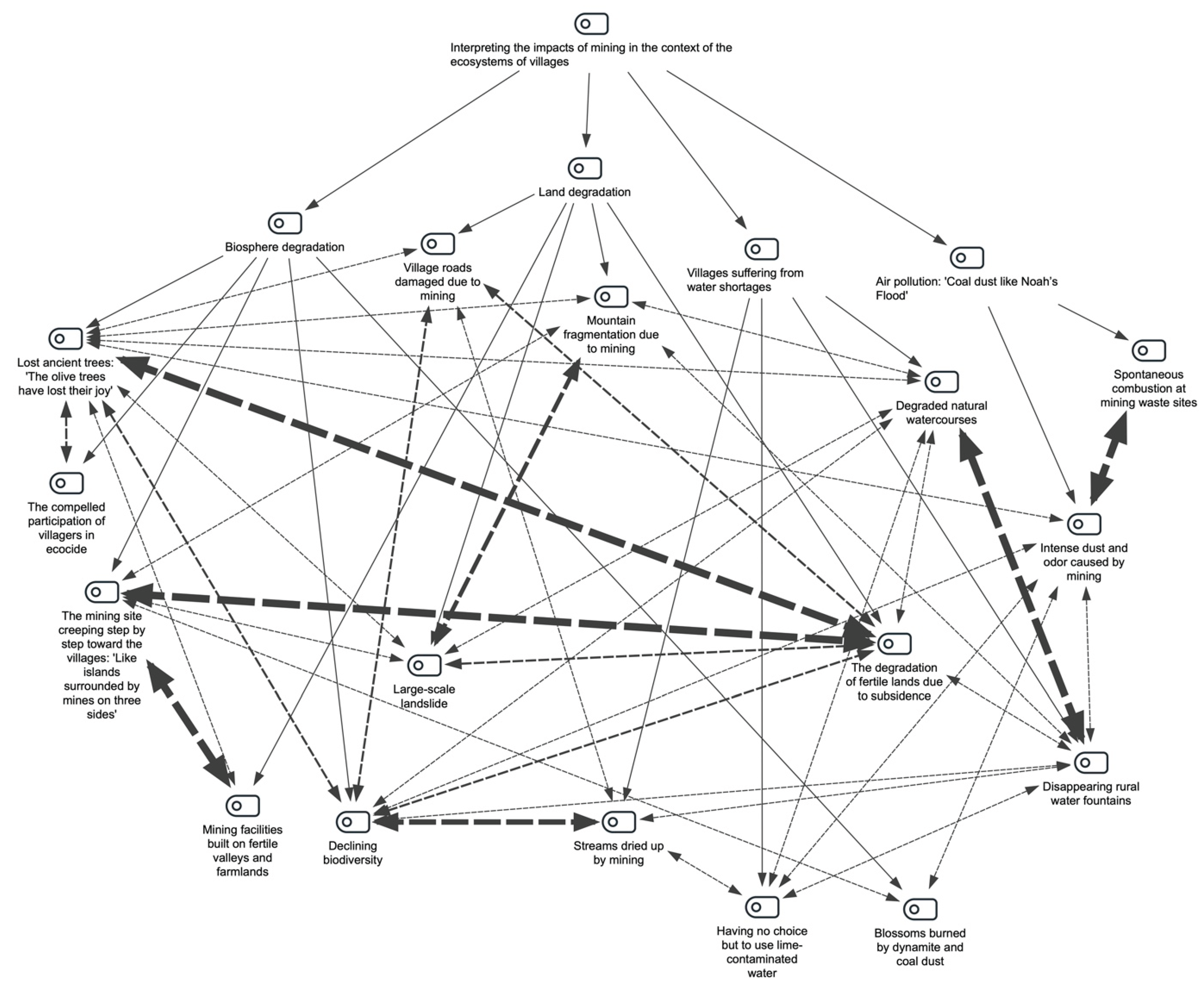

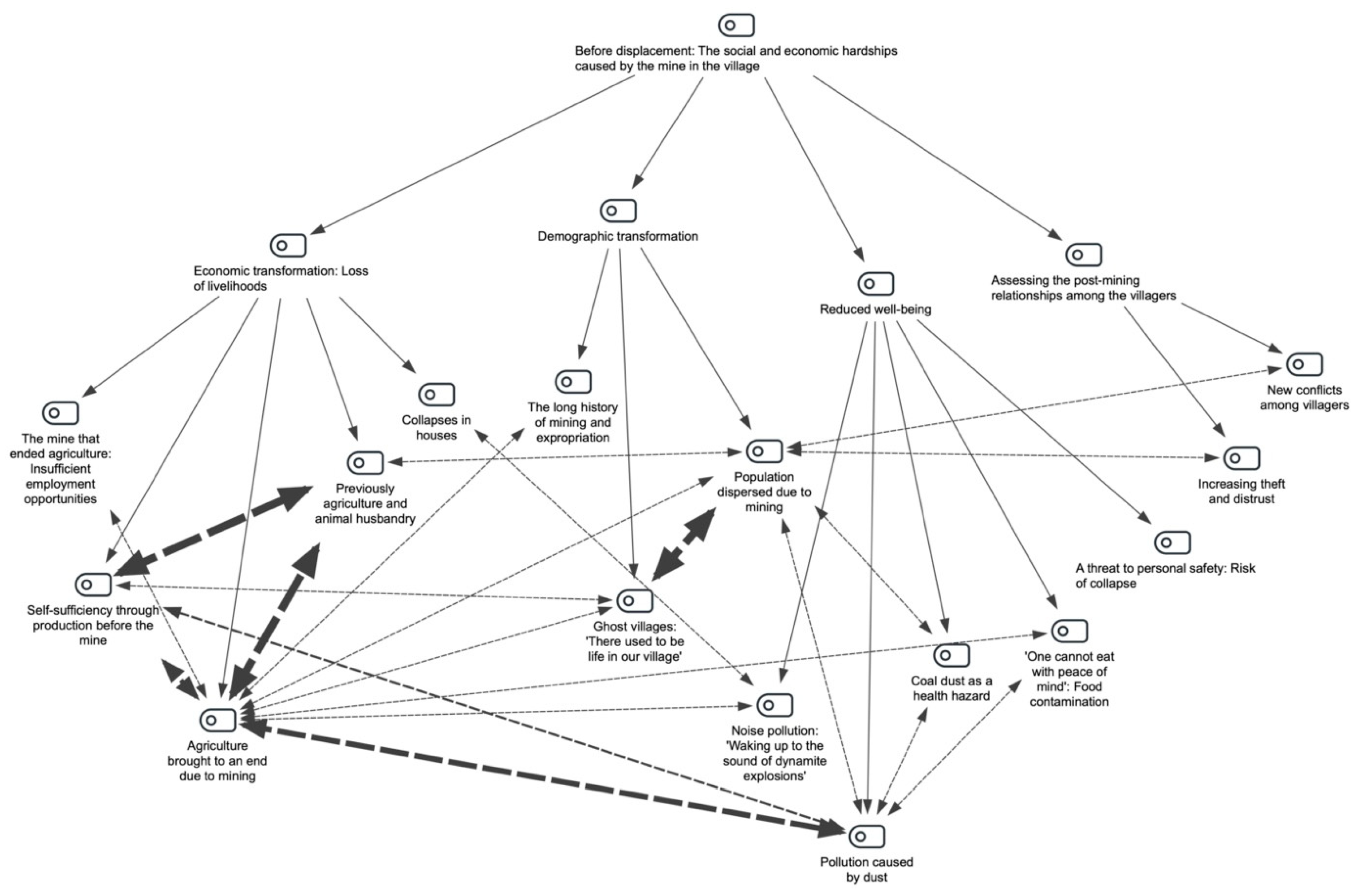

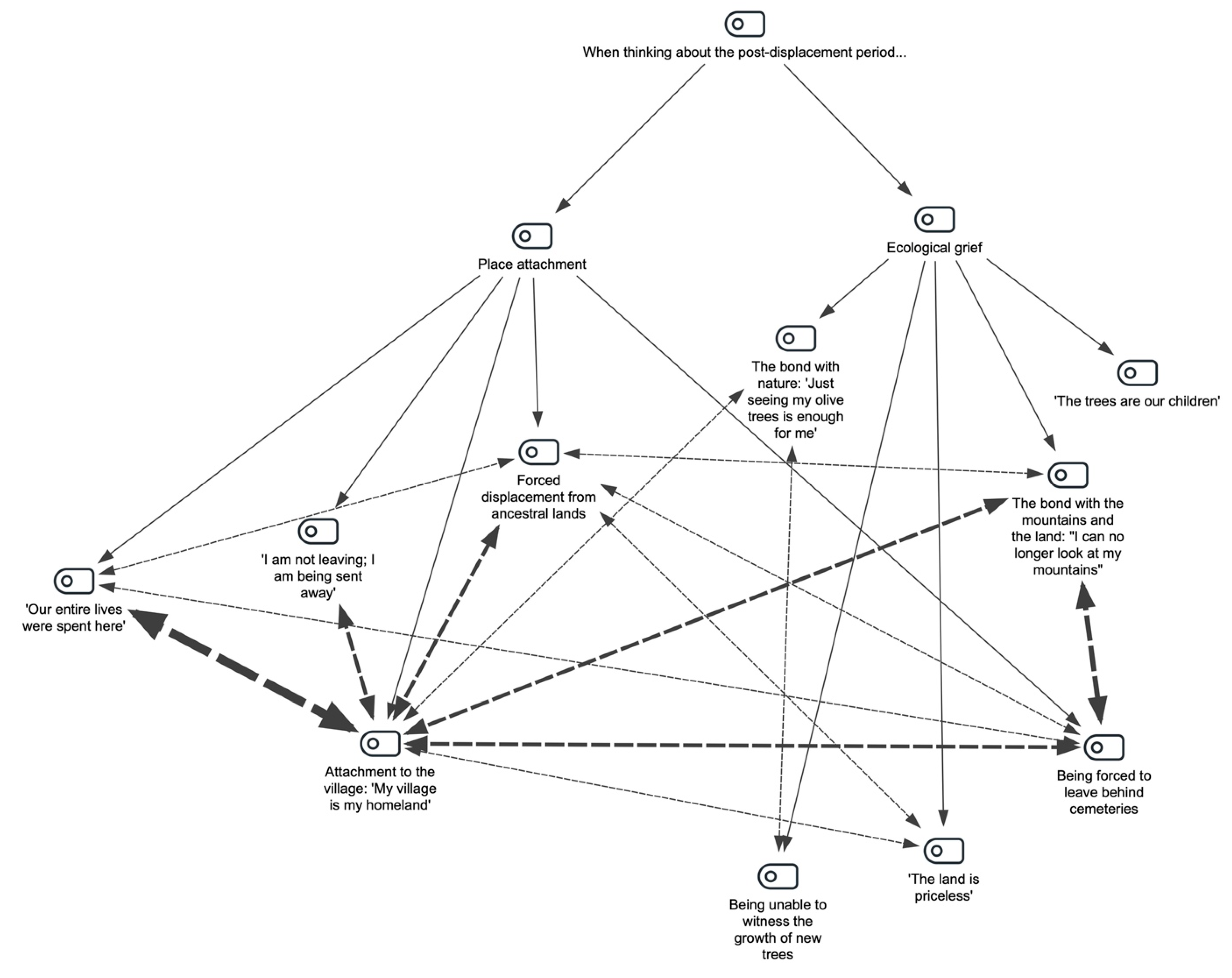

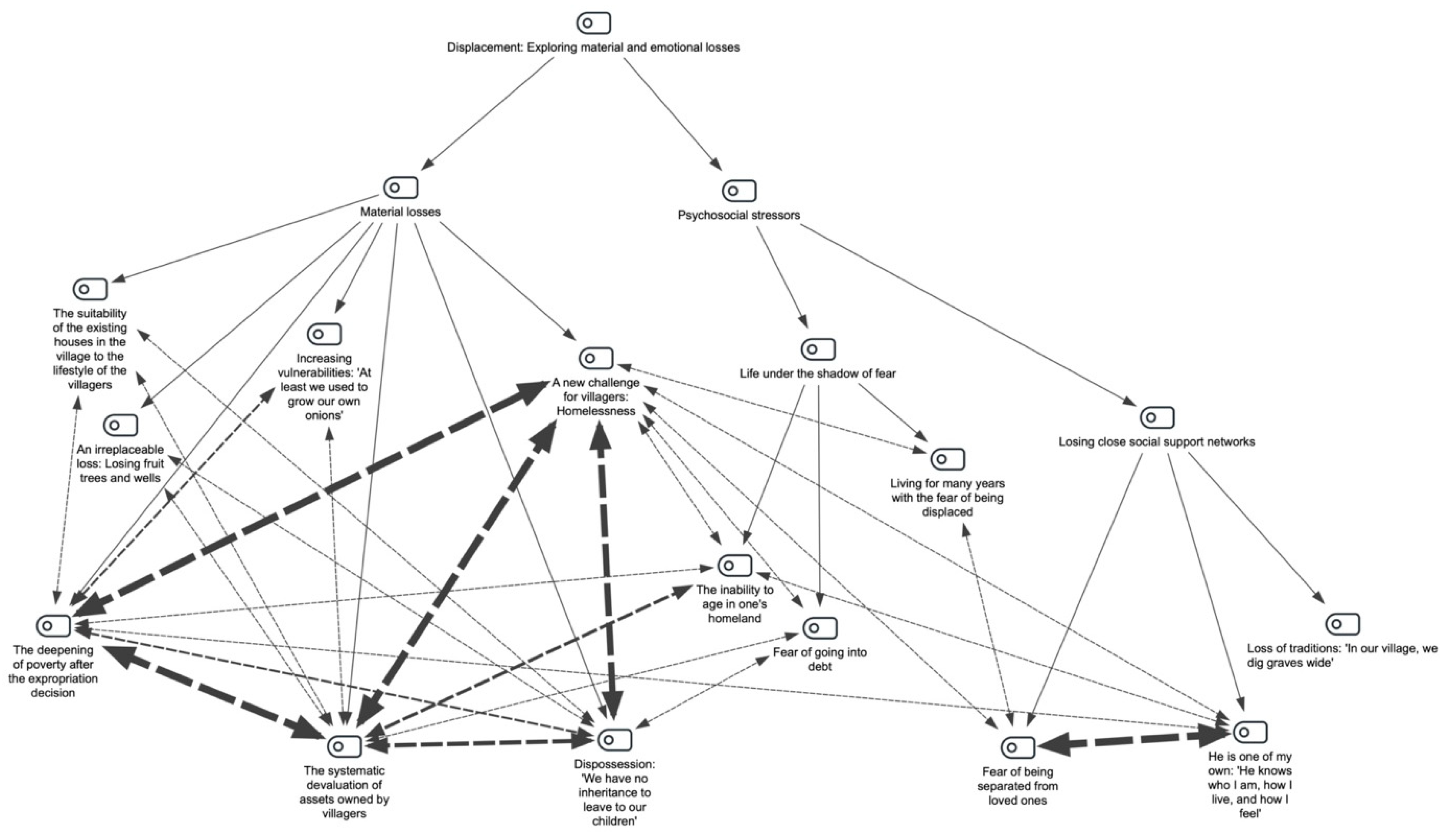

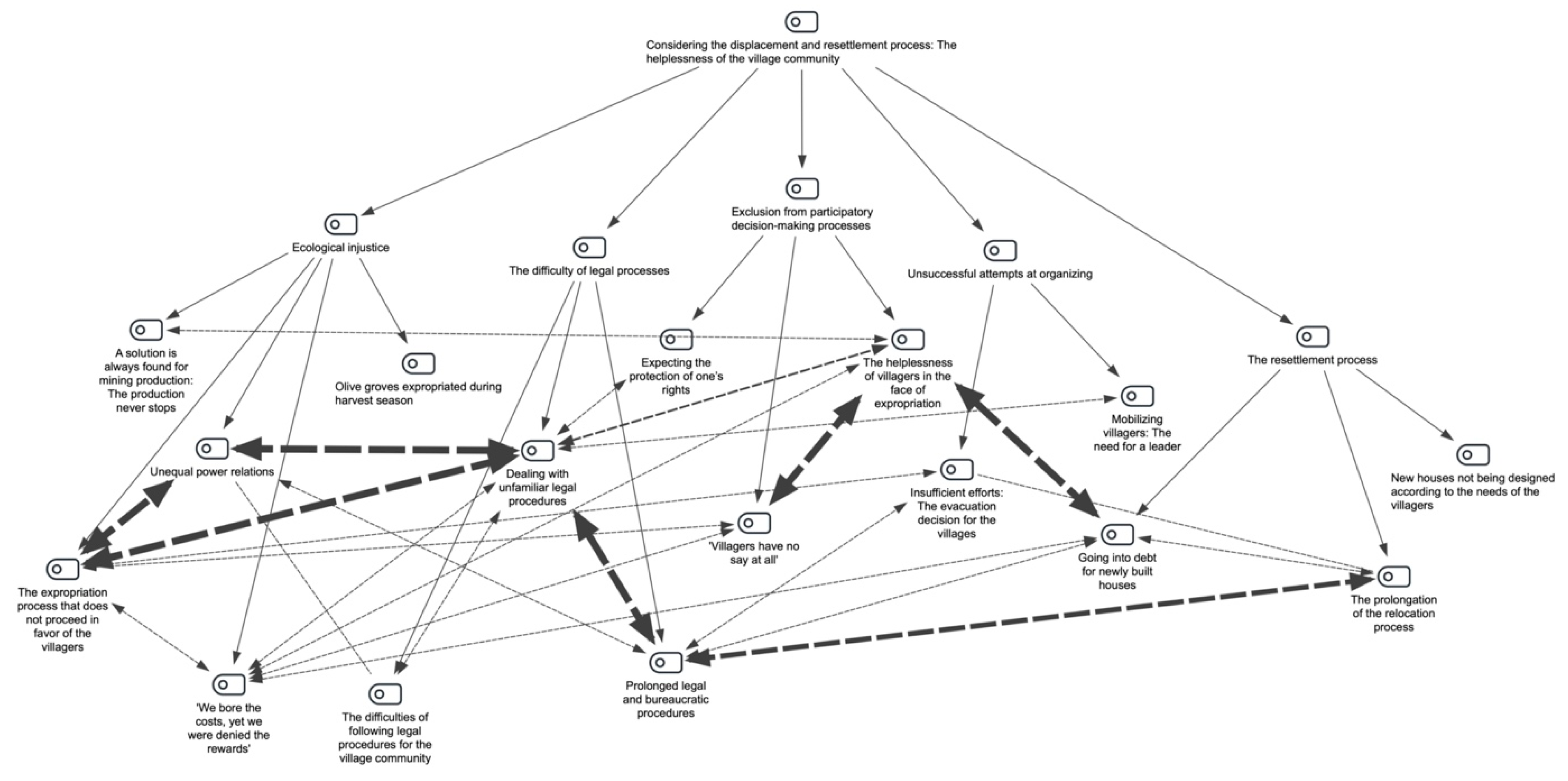

The data collected were analyzed using MAXQDA 2024 software. The analysis was conducted following Braun and Clarke’s (2019) reflexive thematic analysis approach. The analysis began with a review of the interview transcripts and observation notes, during which (i) familiarity with the data was developed. The coding process was then initiated using MAXQDA 2024, and (ii) preliminary codes were generated. In the third step, (iii) potential themes were developed. These themes were then (iv) reviewed, (v) defined, and named. Finally, the reflexive thematic analysis was completed by visualizing the findings in MAXQDA 24 through hierarchical code–subcode models and code relationship models, as shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, resulting in the final version of the research report (vi). In addition, based on the findings, the ecosocial work intervention needs related to mining-induced environmental degradation and displacement were visualized at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels in

Figure 6.

6. Findings

6.1. Reflections on the Impact of Mining Activities on the Villages’ Natural Environment

The theme that emerged in line with the first research question (RQ1) is related to the environmental degradation resulting from mines in villages. Mining activities have a significant effect on all elements of the ecosystem, including the degradation of natural land and aquatic ecosystems and water and air pollution. Air pollution is a salient environmental degradation problem in both villages, which are located almost within the mining sites, with the convergence of mining operations. The villagers explained that the air in their villages was polluted with dynamite, coal dust produced during mining activities, and from combustion events in the waste sites after mining (

Figure 1).

“You can't open your eyes in the summer; it is like Noah’s flood of dust. It is also harmful to health. You don’t have anything to sow.” (P7)

“When the coal meets oxygen, it starts to burn… Since the mine is located in the north, it (coal dust) comes into the village with the wind. Dust, smoke, smell... There’s no place untouched by the dust. It becomes unbearable. It’s like poison...” (P15)

Land degradation is one of the main environmental problems caused by mining activities in Deniş and Eğnez. It is a serious problem that threatens both the environmental balance and livelihoods of rural communities. The construction of mining facilities and landfills on fertile agricultural lands, the deterioration of natural roads in the villages during the extraction and transportation of minerals, and landslides and collapses caused by mineral extraction are among the main causes of the soil/land degradation faced by the villages.

“Our land was mined and collapsed. We had wells in it; we had a lot of water. We had a beautiful garden in our field. We had a very good life. When the mine took over, our fields were restricted.” (P18)

“The olive field collapsed into it... A sinkhole has formed... The mine gets coal from here. Below it was a sinkhole. You would think there’s an earthquake. Dynamite explodes from under it like this. Day and night. It’s like an earthquake is happening.” (P5)

Water degradation is also a significant problem caused by mining activities in both villages (

Figure 1). Mining activities require intensive use of water in processes such as coal washing, processing, and dust suppression. In particular, waste landfills pollute groundwater and lead to the deterioration of water resources. In addition, explosives used to reach mineral deposits destroy natural waterways and divert them. The mining facilities established in the river and stream beds and the waste left in these waters have caused severe water insecurity in villages. The drying up of natural fountains, streams, and ponds has not only threatened the ecosystem but also negatively affected the livelihoods of the villagers.

“... Because of the mine, dynamite is used at work. After that, there are slips. The water bed is deteriorating. The water is going elsewhere... Our livelihood has been restricted because there is no water.” (P18)

“They dried up. There were two streams, and both dried up. They ended up inside the mining site. It used to be beautiful. Agriculture is over here. Farming no longer exists.” (P9)

Evidently, air, soil, water, and biosphere degradation influence and exacerbate each other, as seen in

Figure 1. Moreover, the deterioration of the village ecosystem threatens the food security of the villagers.

“Young people used to dip their baskets like this into the stream. The water would flow and the basket would fill with fish. You could just pick them up and eat them. Those fish were so delicious.” (P6)

“There were a lot of live fish. We used to fish. There were carps. There were a lot of fish in it.” (P9)

Another type of environmental degradation caused by mining activities in the villages is biosphere degradation. This type of degradation has also led to a decrease in the diversity of animals in the villages. This situation can be expressed both as an ecological problem and a threat to the livelihood of the villagers because the mine’s complete removal of natural vegetation did not leave any grazing land for the animals.

“There is damage to the water and everything. There is no place to herd animals now. There is nothing that has not been harmed. There were 50–60 cattle and goats in this village. You know, there’s none left.” (P2)

“I had 17 beehives this year in this mining area across the street. Yesterday, I went and looked and only 2 hives are left. Most of my bees have died, and have turned to dust.” (P14)

“Dust has effects. Where will the bee land? Every collar is dusty. If it lands on the crown of the flower, there is dust; if it lands on the branch of the pine, there is dust. You go out to see the bee, and, come on, there are no bees here because of the dust.” (P8)

The chemicals and coal dust contained in the dynamites used in the mines cause the plants to burn during the flowering period. This situation affects a larger area even beyond the mine site. Consequently, olive groves and other forest areas have been damaged. When we visited the villagers’ olive groves, the leaves of the trees, olives, and other fruits were all covered with dust.

“They’re drying up badly. The olives have no joy.” (P16)

“The fruit doesn’t survive because of this dust. You know, when the trees are in bloom—right at that moment—it releases some dust, ruins them, burns the blossoms… And when does it stick to these trees? It just dries them out.” (P6)

The destruction of olive groves and forests due to mining activities does not stem from coal dust only. Following the expropriation of forested areas and villagers’ agricultural lands, the private companies operating the mining sites demanded that the villagers cut down olive groves and other trees, which would ultimately be destroyed during excavation, even though cutting down olive trees is prohibited by law. This destruction of forests to pave the way for mining activities has been criticized by the public.

“We even cut the olive trees. We looked at it; it is going to the threshing (excavation) now. It will remain under the ground... I have a tree over there now. It’s maybe 700 or 800 years old over there. My father didn’t know when it was planted. My grandfather didn’t know when it was plated either. I mean, the tree trunk is about 2 meters wide.” (P12)

“I was glad when the state said that cutting down olive trees is prohibited. But what’s left anyway? They said it’s forbidden to cut them. The company doesn’t do the cutting itself. They have people cutting down the olive trees they planted themselves. Then it avoids taking any responsibility.” (P16)

6.2. Societal Repercussions of Mining-Induced Environmental Degradation on Villages Prior to Displacement

In line with the second research question (RQ2) of this study, the effects of mining-induced environmental degradation on the demographic structure of the villages were examined. In this context, the villagers stated that even before the decision of displacement due to mining activities had been taken, people had started migrating from the villages mainly because of the difficulties experienced living in the villages. Migration from the villages is closely related to inefficient agriculture due to environmental degradation and the lack of alternative means of livelihood. During the field research, the sparse population in both villages attracted particular attention, with significantly fewer young people and children in the villages.

“It used to be crowded. Everything was good in the neighborhood. There are no people left. Everything is broken. There is nothing left. We don’t have any houses left. We don’t have any fields left.” (P5)

“It was pretty crowded... Everyone started to migrate… Because we can’t farm, because of agriculture...” (P9)

Drying of water resources, deterioration of fields and agricultural lands, and destruction of forests and olive groves due to mining activities are among the main reasons for the cessation of agricultural production in villages. Agricultural activities, including animal husbandry, have become impossible in the villages. The yields of the remaining olive groves have significantly decreased due to coal dust and subsidence of the land, posing a threat to both the livelihoods and food security of the villagers.

“As long as there are collapses, for example, we can’t enter our farmland. It damages trees. We can’t get a yield from olives.” (P4)

“Because of the dust, the plant burns. Nothing grows. Whatever you plant doesn’t grow… During the olive harvest, you can’t even see through the dust in the air. We keep wiping it off, but the dust keeps falling.” (P7)

Before the adverse effects of the mining activities on agricultural production, the villagers were largely able to meet their food needs and earn income from what they produced. Therefore, they were able to ensure the food security and livelihood of their households. However, with the start of mining activities, this situation has changed drastically, severely damaging the food security and livelihoods of the villagers.

“Back then, we were farming. Farming is over now. Everything used to be in abundance in those days. Now, there’s no planting, no harvesting. It doesn’t work anyway because of the dust. Making a living has become much harder.” (P7)

“It was very efficient... We had a field over there on 24 acres. We used to plant wheat for 1 year and not buy any flour for 2 years. Two years was enough.” (P8)

Another example of the economic losses caused by mining activities within the context of this research is the damage to houses. In particular, the progressive underground work in Eğnez under the settlement area has caused cracks to appear in the villagers’ houses.

“There are a lot of cracks in the houses. I evacuated the house, for example.” (P4)

“We are in a difficult situation. Some are afraid that the houses will collapse. There are a lot of cracks in some people’s houses, because of the mine. They’re getting coal out of it.” (P5)

Another major problem caused by mining is the decline in the villagers’ well-being. For instance, the villagers start their day with the sound of dynamites. Food contamination and air pollution are directly related to the deterioration in well-being. Moreover, the safety of villagers is jeopardized by the damage to houses and fields caused by landslides.

“Part of the olive grove slid down the slope. Some of it is still intact. I still go there and harvest olives. We asked the mining company about it. They said, ‘We do not accept any responsibility. If it collapses or anything happens, you can only harvest from the stable part’. So now, we only pick olives from the part that’s still safe...” (P1)

“We go to the fields to harvest olives, but we’re afraid we might fall into a crack. Not going isn’t an option either. Our husbands go to plow the land, and we don’t know if they’ll come back or not—nothing is certain.” (P5)

Furthermore, before the displacement process, that is, during the negotiation process with the companies, significant polarizations and new disputes emerged among the villagers. During the field research, these profound social divisions resulting from mining activities and displacement processes were evident in both villages. These divisions underscore the complex social consequences of mining-induced displacement.

“We're split in two. After that, there were fights, everything happened...” (P13)

“I mean, we are ignorant. The village was divided into two, some bought a house and some did not. We talked a lot at the time, but people talked like that, someone talked like that...” (P15)

6.3. “Is It Easy to Leave Your Ancestral Homeland?”: Material and Spiritual Losses

In this study, two themes emerged in line with the third research question (RQ3). The first theme is related to the ecological grief of the villagers for the loss of their village, and therefore the attachment they had developed with their village and their physical environment. The second theme is related to other material and moral losses experienced by the villagers due to mining.

6.3.1. Place Attachment and Ecological Grief in the Context of Displacement

The first theme is related to the strong sense of place that stands out in the participants’ narratives (

Figure 3). Participants stated that they had deep ties to their villages, referring to the lives they spent there, the importance of their ancestral lands, and the emotional bond they felt with their villages. This deep attachment to place indicates that the village represents not only a physical location but also a deeply embedded part of their identity, ancestry, and history. Despite the environmental and social problems caused by mining, it became evident how difficult it was for them to leave their villages.

“This (land) is from our grandfather and grandmother. Children hold a branch, dig the soil, do something. They don’t know the value of the land; the land is invaluable.” (P8)

“Is it easy to leave your parents’ homeland?” (P3)

“Your childhood was here… I know it, I’ve lived it here. Turkey is my homeland, yes, but Eğnez is like my second homeland. I was born here, lived here, and spent my youth here.” (P17)

Moreover, displacement results in the loss of mosques and cemeteries, which is a significant issue for the participants. Although the option of moving the graves is on the agenda, villagers are hesitant to move the graves, especially owing to religious reasons.

“Our cemetery will remain. Where could we even take it? It’s heartbreaking, deeply painful. So much pain. So much pain...” (P1)

“My soul is here, and my funeral will be here. The graves are full of our ancestors. If you go into the city, when you come here, when you enter the house, we say ‘Oh well!’.” (P5)

This study reveals an interaction between eco-grief, eco-spirituality, and displacement. Specifically, this eco-grief experienced by the villagers is often intertwined with beliefs and practices that emphasize the interconnectedness of man and nature, that is, eco-spirituality. Participants expressed the emotional hardships they experienced due to mining-induced environmental degradation and displacement, often referring to the connection they established with their natural environment. This situation became particularly evident when participants spoke about the emotional distress they experienced upon having to cut down their olive trees.

“How will my hand reach out and cut the olive trees? I sat down with my wife and said, ‘Well, my tree, I watered you a lot, but this is fate’. My wife started crying, but what are you going to do? We cut it off.” (P10)

6.3.2. Villagers’ Material Losses and Loss of Social Support Networks in the Context of Displacement

Mining-induced displacement is closely related to the social and economic effects that follow the dispossession of individuals. This study identified psychosocial difficulties related to displacement. The villagers understood the significance of the loss of their social support networks (

Figure 4).

“There are 55 people’s homes—that’s the saddest part. Behind that, there are 55 to 60 households. These households are left outside… So, what will those people do? No matter what, they are my fellow villagers. They’ve known me for years—they know my ways, my habits, my character, they know everything. I can’t be friends with someone new just like that. It would take 20 years to build that kind of bond.” (P15)

Moreover, a fundamental issue is that older villagers may not be able to grow old in their villages. The relocation and eviction process has already been a part of their lives for many years. The resettlement houses being built for older villagers are significantly more expensive than the expropriated homes they once owned, and many of them are unable to take on new debt. Consequently, villagers may be exposed to the risk of entering a long-term debt cycle that may last up to 20 years.

“Now it’s not possible for me to get a house there. I’ll have to go into debt. I’m already 61 years old. How am I supposed to save that money and pay it off at this age?” (P1)

“You see, this is what really upsets me. Every day I go to bed and wake up thinking: where will I go, where will I stay? Where will I find a place to live? That’s my constant worry. What can I do? This anxiety even comes into my dreams—this uneasiness.” (P7)

Another crucial problem faced by villagers in the process of displacement includes financial losses. While the villagers face the risk of being homeless, landless, and without olive trees (dispossession), they are compensated with only one house, which they will have to pay for for nearly 20 years. The compensation paid for their houses, fields, and olive groves is insufficient to afford a new house in the relocated village. Therefore, this situation creates new vulnerabilities for the villagers. The fears about the displacement process for older and lonely individuals, especially single older women, which were not present in their verbal expressions, were clearly observed during the research.

“We didn’t ask for money—if only they had built houses like our own. We didn’t want money… Even my children and I are in debt now.” (P5)

“Rent.... They say rents are also very expensive... I receive an old-age pension. Should I pay rent with it or take care of myself?” (P7)

As the findings reveal, ownership of land is a crucial factor that protects the villagers against food insecurity, which is now likely to grow because they will lose their land, houses, and barns but will be compensated with only houses in the newly built villages.

“Everything is so expensive now. But here, we have our garden, and we make our own cheese and yogurt. The hens lay five eggs a day, and that’s enough.” (P16)

“Now we grow at least our onions and garlic little by little enough to eat them ourselves. How are we going to do it there? We have quince in our courtyard, we have everything. What are we going to do there?” (P6)

6.4. Exploring the Process of Mining-Induced Displacement and Resettlement from the Perspective of the Villagers

The final theme emerging in line with the fourth research question (RQ4) is related to the processes of displacement and resettlement. In this research, ecological injustice is especially prominent in the processes of displacement and resettlement. Ecological injustice refers to power imbalances that perpetuate injustice to both the natural environment and vulnerable populations. Therefore, the inability of the villagers to benefit from mining, the lack of adequate consideration of the needs and interests of the villagers, and power imbalances between the villagers and the mining companies are considered ecological injustices (

Figure 5).

“If I was born and raised on that land and now, I’m paying the price for it, then of course I have the right to benefit from it.” (P9)

“They sell coal under the name of this village. But no one gives anything to the village.” (P17)

In addition, the problem of injustice and power imbalance has led to the exclusion of villagers from decision-making processes. Although they were directly affected by the expropriation process, their access to accurate information about the process was very limited.

“... Why is this drilling (drilling for the mine) being installed? You know, what are you doing here? They set it up by drilling boreholes. But we don’t know why. Are they looking for water, or are they looking for coal? They don’t explain. They don’t explain this to the villagers. They say we are looking for water. They give an evasive answer. They’re passing it off.” (P18)

Another problem related to this situation is that the consent of the villagers as property owners is not sought in the process of expropriation in the public interest. Meanwhile, the villagers do not have the right to object to relinquishing their property due to the Expropriation Law (1983). They can only apply for legal recourse regarding the level of compensation for their property. However, even if they file a lawsuit, the compensation paid does not change or is only slightly increased.

“They passed a law from the Council of Ministers in our mining area. You can’t stand against the decision in the parliament...” (P4)

“I didn’t have a chance to say no. The court process continued. The company said you can also file a complaint. ‘The court channel is open, but I am confiscating the field’, he said. He went into the field, and we couldn’t intervene... You can’t interfere at all... He doesn’t even ask you...” (P12)

During the interviews, the villagers stated that the most difficult issue was managing the court process against the companies. Most villagers have given up on initiating the court process for reasons such as lack of familiarity with the legal processes, insufficient resources to hire lawyers, and long-drawn-out legal processes. Moreover, the long bureaucratic procedures involved in the relocation and resettlement processes have exacerbated the situation for the villagers.

“The company hired 5 lawyers for you and sued you. What are you going to do? You don’t have any lawyers...” (P12)

“It takes a long time. Now the district court has concluded. The local court gave us a value, and they paid our money. We did not accept those values; we appealed. We don’t know what will come out in the appeal, and from there, it will still go all the way to the Supreme Court.” (P14)

Another problem faced by the villages during the resettlement process is the debt they will incur for the newly built houses. Although the payment terms for the houses have been improved for the villagers, they will still find it difficult to pay off their debts for approximately 20 years. In addition, almost half of the people from both villages would not qualify for homeownership in the newly built villages for various reasons.

“I don’t want to leave the village. For example, the company bought a house here for 150 thousand liras, and now they’re going to offer me a new one over there for 700–800 thousand, maybe even a million. How is an ordinary person supposed to afford that?” (P17)

“They bought my house for 300 thousand liras, and now the new house will be around one million. How am I supposed to pay one million? I have no pension, no job, no income.” (P14)

This study highlights the need to build communities for villagers, who lack a common strategy against mining-induced displacement. Their inability to come together and attract public attention has prevented their voices from being heard.

“She didn’t resist, in our village, my daughter didn’t resist...” (P7)

“... How are you going to put your foot down, girl? When there is no unity...” (P13)

7. Discussion

This study assessed mining-induced environmental degradation and displacement from the perspective of two Turkish villages currently experiencing these issues. The findings highlight the multidimensional adverse impacts of mining activities in rural areas. The research reveals the connection between mining operations and deforestation, land degradation, biodiversity loss, depletion of natural resources, and air, soil, and water pollution (Arkoc et al., 2016; Atmış et al., 2024; Gençay & Durkaya, 2023; Tozsin & Öztaş, 2023), thereby showing how these activities threaten the livelihoods of rural communities in particular (Hinojosa, 2013; Hota and Behera, 2016; Ofori et al., 2023; Sosa et al., 2017). As ecosocial work emphasizes, this relationship can be interpreted as evidence that environmental sustainability and social well-being are deeply interconnected (Boetto, 2025; Nöjd et al., 2024). These challenges may be seen as an opportunity for ecosocial practitioners to develop interventions that promote the sustainable livelihoods of individuals and, by extension, communities.

The way mining activities harm farmers’ natural and human capital, disrupting the ability of rural households to sustain their lives (Ofori et al., 2023; Zhao and Niu, 2023), and exacerbate existing vulnerabilities by causing displacement (Lèbre et al., 2020), is closely related to the notion of ecological justice, which lies at the core of ecosocial work. Ecological justice highlights that those most affected by environmental degradation are often communities left vulnerable due to structural inequalities and limited participation in decision-making processes (Gray and Coates, 2012; Gray et al., 2013). As this research shows, rural communities dependent on common lands and with limited power to defend their rights are disproportionately impacted by mining-related environmental destruction and displacement (Matanzima, 2024; Oskarsson et al., 2024). Ecosocial work frames these injustices not only through a human rights lens but also through a holistic conception of justice—ecological justice—which considers both human and ecosystem well-being (Ramsay and Boddy, 2017). In this context, ecosocial practitioners are responsible not only for supporting rights-based advocacy and developing interventions to build the resilience of rural communities but also for protecting the integrity and rights of the natural environment.

Ecosocial work acknowledges that environmental degradation is a form of injustice rooted in structural inequalities (Besthorn and McMillen, 2002; Willet, 2017). Thus, anti-oppressive intervention is a vital dimension of ecosocial practice (Shackelford et al., 2023; Wang and Altanbulag, 2022). As demonstrated by this study, land is often purchased after the discovery of mineral reserves; however, when deemed necessary, the state resorts to expropriation on the grounds of public interest without the consent of landowners (Baddianaah et al., 2022). Such land acquisition processes force local communities to abandon their ancestral lands, resulting in the loss of homes, property, and traditional livelihoods (Mondal & Mistri, 2021). Displaced individuals and communities often face multidimensional problems such as land loss, lack of access to resources, housing and income insecurity, weakening of social support networks, food insecurity, rights violations, and spiritual hardship (Huang et al., 2023; Manduna, 2023a). Therefore, it is essential for ecosocial workers to work in solidarity with individuals, groups, and communities to expose oppressive structures, strengthen rights-based advocacy, and support active community participation in decision-making processes.

Unjust distribution of benefits from mining projects and depriving communities of adequate compensation or fair resettlement deepen the problem of injustice (Manduna, 2023b). As this research also demonstrates, merely paying the value of land and houses is not sufficient for communities displaced by mining (Wilson, 2019). Compensation should also be provided for other losses, such as cultural values that may be lost during displacement. However, in developing countries, mining-related displacement often results in inadequate compensation. This inadequacy and injustice primarily stem from the lack of negotiation with displaced and resettled people (Manduna, 2023a; Magazzino, 2024; Opoku et al., 2024). As is the case in this study, mining companies often exclude rural communities from decision-making processes (Huang et al., 2017). This situation should be seen by ecosocial practitioners not only as a problem area but also as an intervention space requiring a political stance against structural inequalities, a strengthening of rights-based advocacy, and leadership for justice (Ramsay & Boddy, 2017). Additionally, ecosocial workers may collaborate with local communities in efforts such as environmental advocacy, community-based initiatives, voluntary resource mobilization, and coalition building to help prevent mining-related environmental degradation (Androff et al., 2017).

As the present research also shows, population decline and intra-community conflicts resulting from mining activities over time contribute to the weakening of social bonds (Bell, 2009; Mactaggart et al., 2016). Especially after displacement, communities experience the loss of social relations and sacred places, which in many cases is considered more significant than material losses (Khan et al., 2021; Manduna, 2023a; Ofori et al., 2023). Therefore, the most devastating risk in mining-induced displacement is community disintegration caused by the loss of informal support networks that sustain livelihoods (Ghosh, 2024). Furthermore, for individuals with a strong attachment to place, relocation to another region is often undesirable. Environment-transforming activities like mining may be perceived as threats due to the deep emotional and spiritual ties local populations have with their surroundings (Walker et al., 2015). For them, place transcends the physical realm and represents a shared space of existence where the natural environment, social relations, and spiritual meanings converge (Askland, 2018).

Mining companies, in addition to the physical destruction they cause, also negatively affect the cultural and spiritual relationships that communities have with the land (Mactaggart et al., 2016). As this study illustrates, rural communities’ ecospiritual bonds with the land are damaged in the face of environmental degradation and displacement. This has brought ecological grief to the forefront. As an emotional response to the loss of cherished places, species, and ecosystems, ecological grief may lead to feelings of despair, fear, and identity loss (Qiu & Qiu, 2024). However, ecological mourning is not an emotion that should be suppressed. On the contrary, it can foster resilience and serve as a foundation for meaningful action. Such transformation can be enabled through professional support and collective action (Ágoston et al., 2022). In this context, ecosocial work offers a framework for integrating eco-spiritual connections into social work interventions. This approach can serve as a foundation for advocating not only for human rights but also for the rights of nature (Chigangaidze, 2023).

8. Conclusion

This study reveals that in cases of mining-induced environmental degradation and displacement in rural areas, there is a critical need for multidimensional ecosocial work interventions at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels. At the micro level, psychosocial support services are essential to help individuals and families cope with the emotional impacts of mining-related environmental degradation and displacement, such as trauma, grief, and ecological loss. These interventions should take into account individuals’ spiritual connections with nature. Additionally, the destruction of villagers’ livelihoods has led to increased economic vulnerability, making it necessary to co-develop alternative and sustainable livelihood strategies with local communities. At the mezzo level, developing collaboration-based interventions with organizations focused on environmental sustainability has emerged as a key responsibility for ecosocial workers. In this context, supporting capacity- and skill-building processes among diverse and disadvantaged groups stands out as a crucial area of mezzo-level intervention. At the macro level, political and societal interventions are needed to address structural inequalities and to strengthen the collective rights of rural communities. Given that displacement weakens social ties, rebuilding community relations through grassroots organizing, collective action, and legal advocacy is vital—not only to make rights-based demands visible but also to support the restoration of disrupted community cohesion. However, these levels are not separated by rigid boundaries; rather, the interventions are often intertwined and mutually reinforcing. As illustrated in

Figure 6, what lies at the intersection of all levels is the advocacy for ecological justice, which acknowledges the interdependence of human well-being and environmental sustainability, and reflects a commitment to justice for all living beings.

An important limitation of this study was the significant migration of the younger population to urban centers due to mining-induced environmental degradation, which made it difficult to reach them. Additionally, it was observed that some villagers were hesitant to participate in the study due to fear of private mining companies. Future research could explore the lives of displaced villagers in their new settlements after the relocation process is completed, in order to more comprehensively examine the social, economic, and emotional impacts of resettlement. In this context, longitudinal studies and research focusing on the psychological dimensions, which could not be addressed in depth in the present study, are especially needed.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for the present study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Ankara University on 04/03/2024, with the decision number 56786525-050.04.04.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing financial or personal interests related to this work.

References

- Ágoston, C., Urbán, R., Nagy, B., Csaba, B., Kőváry, Z., Kovács, K., Varga, A., Dúll, A., Mónus, F., Shaw, C. A., & Demetrovics, Z. (2022). The psychological consequences of the ecological crisis: Three new questionnaires to assess eco-anxiety, eco-guilt, and ecological grief. Climate Risk Management, 37, 100441. [CrossRef]

- Androff, D., Fike, C., & Rorke, J. (2017). Greening social work education: Teaching environmental rights and sustainability in community practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(3), 399–413. [CrossRef]

- Annor, F., Annor, S., & Abdul-Nasiru, I. (2024). “In my own land, I am treated like a foreigner”: Mining-induced challenges and psychological distress among farmers in ghanaian mining communities. Society & Natural Resources, 37(9), 1359–1377. [CrossRef]

- Arkoc, O., Ucar, S. & Ozcan, C. (2016). Assessment of impact of coal mining on ground and surface waters in Tozaklı coal field, Kırklareli, northeast of Thrace, Turkey. Environ Earth Sci, 75, 514. [CrossRef]

- Askland, H.H. (2018). A dying village: Mining and the experiential condition of displacement. The Extractive Industries and Society, 5(2), 230–236. [CrossRef]

- Atmiş, E., Yıldız, D., & Erdönmez, C. (2024). A different dimension in deforestation and forest degradation: Non-forestry uses of forests in Turkey. Land Use Policy, 139, 107086. [CrossRef]

- Baddianaah, I., Baatuuwie, B. N., & Adongo, R. (2022). Socio-demographic factors affecting artisanal and small-scale mining (galamsey) operations in Ghana. Heliyon, 8(3), e09039. [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.E. (2009). “There ain’t no bond in town like there used to be”: The destruction of social capital in the west Virginia coalfields. Sociological Forum, 24: 631-657. [CrossRef]

- Besthorn, F.H., & McMillen, D.P. (2002). The oppression of women and nature: Ecofeminism as a framework for an expanded ecological social work. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 83(3), 221–232.

- Boetto, H. (2017). A Transformative eco-social model: Challenging modernist assumptions in social work. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), 48–67. [CrossRef]

- Boetto, H. (2025). Promoting sustainable development in the Australian Murray-Darling basin: Envisioning an EcoSocial work approach. Sustainable Development, 33(1), 904–915. [CrossRef]

- Boetto, H., Bowles, W., Närhi, K., & Powers, M. (2020). Raising awareness of transformative ecosocial work: Participatory action research with Australian practitioners. Int J Soc Welfare, 29: 300-309. [CrossRef]

- Boetto, H., Bowles, W., Ramsay, S., Shephard, M., & Cordoba, P. S. (2024). Australian perspectives on environmental practice: A national survey with human service professionals. Journal of Social Work, 24(6), 746-776. [CrossRef]

- Boone Barrera, E. (2019). Extractive industries and investor–state arbitration: Enforcing home standards abroad. Sustainability, 11(24), 6963. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Brown, D., Begou, B., Clement, F., Coolsaet, B., Darmet, L., Gingembre, M., Harmáčková, Z.V., Martin, A., Nohlová, B., & Barnaud, C. (2024). Conceptualising rural environmental justice in Europe in an age of climate-influenced landscape transformations. Journal of Rural Studies, 110, 103371. [CrossRef]

- Cashwell, S. (2024). Bringing environmental justice to the practice setting: Putting the environment in person-in-environment. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 1-8. 10.1007/s41134-024-00323-1.

- Chang, E., Sjöberg, S., Turunen, P., & Rambaree, K. (2025). A call for ecosocial community work: challenges and possibilities for ecosocial work in local neighbourhoods in Sweden. European Journal of Social Work, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Chigangaidze, R. K. (2022). The environment has rights: Eco-spiritual social work through ubuntu philosophy and Pachamama: A commentary. International Social Work, 66(4), 1059-1063. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M., & Christensen, C. (2024). From the Gezi Park protests to the Akbelen Forest: Care in the context of democracy and political dissent. Environmental Communication, 18(1–2), 173–177. [CrossRef]

- Elvan, O.D. (2013). The legal environmental risk analysis (LERA) sample of mining and the environment in Turkish legislation. Resources Policy, 38(3), 252–257. [CrossRef]

- Gençay, G., & Durkaya, B. (2023). What is meant by land-use change? Effects of mining activities on forest and climate change. Environ Monit Assess, 195, 778. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D. (2024). Aspects of development: Voices from predisplacement site in Eastern India. The Extractive Industries and Society, 19, 101517. [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. and Coates, J. (2012), Environmental ethics for social work: Social work's responsibility to the non-human world. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21: 239-247. [CrossRef]

- Gray, M., & Coates, J. (2013). Changing values and valuing change: Toward an ecospiritual perspective in social work. International Social Work, 56(3), 356-368. (Original work published 2013). [CrossRef]

- Gray, M., Coates, J., & Hetherington, T. (2013). Introduction: Overview of the last ten years and typology of ESW. In M. Gray, J. Coates, & T. Hetherington (Eds.), Environmental social work (pp. 1–29). Routledge.

- Gukurume, S., & Tombindo, F. (2023). Mining-induced displacement and livelihood resilience: The case of Marange, Zimbabwe. The Extractive Industries and Society, 13, 101210. [CrossRef]

- Günşen, H.B., & Atmiş, E. (2019). Analysis of forest change and deforestation in Turkey. The International Forestry Review, 21(2), 182–194. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27101468.

- Hinojosa, L. (2013). Change in rural livelihoods in the Andes: Do extractive industries make any difference?. Community Development Journal, 48(3), 421–436. [CrossRef]

- Hota, P., & Behera, B. (2016). Opencast coal mining and sustainable local livelihoods in Odisha, India. Miner Econ, 29, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., Khan, G. D., & Yoshida, Y. (2023). Assessing health and dietary issues of households displaced due to the Aynak Copper Mine Project, Afghanistan. The Extractive Industries and Society, 13, 101299. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Faysse, N., & Ren, X. (2017). A multi-stakeholder platform involving a mining company and neighbouring villages in China: Back to development issues. Resources Policy, 51, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- Jacka, J.K. (2018). The anthropology of mining: The social and environmental impacts of resource extraction in the mineral age. Annual Review of Anthropology, 47, 61–77.

- Khan, G. D., & Temocin, P. (2022). Human right-based understanding of mining-induced displacement and resettlement: A review of the literature and synthesis. Journal for Social Sciences, 6(2), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Khan, G. D., Yoshida, Y., Katayanagi, M., Hotak, N., & Caro-Burnett, J. (2021). Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Afghanistan's Aynak mining community: Exploring the right to fair compensation. Resources Policy, 74, 102285. [CrossRef]

- Kvam, A., & Willett, J. (2019). “Mining is like a search and destroy mission”: The case of Silver City. Journal of Community Practice, 27(3–4), 388–403. [CrossRef]

- Lèbre, É., Stringer, M., & Svobodova, K. (2020). The social and environmental complexities of extracting energy transition metals. Nat Commun, 11, 4823. [CrossRef]

- Mactaggart, F., McDermott, L., Tynan, A. & Gericke, C. (2016). Examining health and well-being outcomes associated with mining activity in rural communities of high-income countries: A systematic review. Aust. J. Rural Health, 24: 230-237. [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C. (2024). The impact of conflicts in the mining industry: A case study of a gold mining dispute in Greece. Resources Policy, 97, 105292.

- Manduna, K. (2023a). Extractive industries indigenisation, displacement and vulnerabilities: The case of Arda Transau, Zimbabwe. Extractive Industries and Society, 14, 101223. [CrossRef]

- Manduna, K. (2023b). Are mining-induced displacement and resettlement losses compensable? Evidence and lessons from mining communities in Zimbabwe. The Extractive Industries and Society. 15. 101281. 10.1016/j.exis.2023.101281.

- Matanzima, J. (2024). Displaced by the transition: The political ecology of climate change mitigation, displacements and Lithium extraction in Zimbabwe. The Extractive Industries and Society, 101572.

- Matthies, A., Peeters, J., Hirvilammi, T., & Stamm, I. (2020). Ecosocial innovations enabling social work to promote new forms of sustainable economy. International Journal of Social Welfare, 29, 378–389. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, R. & Mistri, B. (2022). Impact of displacement on place attachment, landscape value and trust in the Sonepur–Bazari open cast coal mining area, Raniganj Coalfield, West Bengal. GeoJournal, 87, 3187–3201.

- Morley, J., Buchanan, G., & Mitchard, E.T.A. (2022). Quasi-experimental analysis of new mining developments as a driver of deforestation in Zambia. Sci Rep, 12. [CrossRef]

- Mtero, F. (2017). Rural livelihoods, large-scale mining and agrarian change in Mapela, Limpopo, South Africa. Resources Policy, 53, 190–200. [CrossRef]

- Närhi, K., & Matthies, A.L. (2016). The ecosocial approach in social work as a framework for structural social work. International Social Work, 61(4), 490-502. [CrossRef]

- Närhi, K., Matthies, A.L., Stamm, I., & Hirvilammi, T. (2025). Social work practitioners’ views of ecosocial work. Journal of Social Work, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N., Boruff, B., & Tonts, M. (2018). Fool’s gold: Understanding social, economic and environmental impacts from gold mining in Quang Nam Province, Vietnam. Sustainability, 10(5), 1355. [CrossRef]

- Nöjd, T., Kannasoja, S., Niemi, P., Ranta-Tyrkkö, S., & Närhi, K. (2024). Ecosocial work among social welfare professionals in Finland: Key learnings for future practice. International Journal of Social Welfare, 33(3), 732–744. [CrossRef]

- Ofori, R., Takyi, S.A., & Amponsah, O. (2023). Mining-induced displacement and resettlement in Ghana: an assessment of the prospects and challenges in selected mining communities. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min, 13, 61. [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, P., Krishnan, R., & Lahiri-Dutt, K. (2024). Living with coal in India: A temporal study of livelihood changes. The Extractive Industries and Society, 17, 101437. [CrossRef]

- Owen, J. R., Kemp, D., Lechner, A. M., Ern, M. A. L., Lèbre, É., Mudd, G. M., Macklin, M. G., Saputra, M. R. U., Witra, T., & Bebbington, A. (2024). Increasing mine waste will induce land cover change that results in ecological degradation and human displacement. Journal of Environmental Management, 351, 119691. [CrossRef]

- Parra Ramajo, B., & Prat Bau, N. (2024). The responsibilities of social work for ecosocial justice. Social Sciences, 13(11), 589. [CrossRef]

- Powers, M., Schmitz, C., & Beckwith Moritz, M. (2019). Preparing social workers for ecosocial work practice and community building. Journal of Community Practice, 27(3–4), 446–459. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S., & Qiu, J. (2024). From individual resilience to collective response: reframing ecological emotions as catalysts for holistic environmental engagement. Front. Psychol, 15:1363418. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1363418.

- Ramsay, S., & Boddy, J. (2017). Environmental social work: A concept analysis. The British Journal of Social Work, 47(1), 68–86. [CrossRef]

- Ranta-Tyrkkö, S., Forde, C., & Lievens, P. (2024). Introduction: Addressing the role of the social professions in the sustainability transition. In C. Forde, S. Ranta-Tyrkkö, P. Lievens, K. Rambaree, & H. Belchior-Rocha (Eds.), Teaching and learning in ecosocial work: Concepts, methods and practice (pp. 17-37). Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Shackelford, A., Rao, S., Krings, A., & Frances, K. (2024). Abolitionism and ecosocial work: Towards equity, liberation and environmental justice. The British Journal of Social Work, 54(4), 1402–1419. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, M., Boelens, R., & Zwarteveen, M. (2017). The Influence of Large Mining: Restructuring Water Rights among Rural Communities in Apurimac, Peru. Human Organization, 76(3), 215–226. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S., Mathias, J. & Krings, A. (2019). The future of environmental social work: Looking to community initiatives for models of prevention. Journal of Community Practice, 27:3-4, 414-429. [CrossRef]

- Tiamgne, X.T., Kalaba, F.K., & Nyirenda, V.R. (2022). Mining and socio-ecological systems: A systematic review of Sub-Saharan Africa. Resources Policy, 78, 102947. [CrossRef]

- Tozsin, G. & Öztaş, T. (2023). Plant nutrient contents and spatial distribution patterns of toxic element concentrations in mine site soils. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 47(1). [CrossRef]

- Twerefoo, P.O. (2021). Mining-induced displacement and resettlement policies and local people’s livelihoods in Ghana. Development in Practice, 31(6), 816–827. [CrossRef]

- Walker, I., Leviston, Z., Price, J., & Devine-Wright, P. (2015). Responses to a worsening environment: relative deprivation mediates between place attachments and behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol., 45: 833–846. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., & Altanbulag, A. (2022). A concern for eco-social sustainability: Background, concept, values, and perspectives of eco-social work. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Willett, J. (2017). Micro disasters: Expanding the social work conceptualization of disasters. International Social Work, 62(1), 133-145. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.A. (2019). Mining-induced displacement and resettlement: The case of rutile mining communities in Sierra Leone. Journal of Sustainable Mining, 18(2), 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q., & Niu, K. (2023). Blessings or curses? – The bittersweet impacts of the mining industry on rural livelihoods in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 421, 138548.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).