1. Introduction

The practice of stone quarrying has existed since ancient times [

1,

2]. Stone quarrying has evolved from manual methods to more advanced technologies over time, but it still employs traditional methods. In recent years, sandstone quarrying has become a globally recognized industry that significantly contributes to the economies of many countries [

3,

4]. Similarly, the expansion of extractive industries has sparked debates around development, environmental justice, and the spatial unevenness of risk and reward [

5,

6]. Regardless of settled landscapes, resource extraction is frequently depicted as a development driver, offering employment and infrastructure while also contributing to adverse environmental and societal impacts. Quarrying contributes to employment, government revenue, and foreign investment [

7], which has driven liberalization across many African economies. However, the same economic promise often coincides with weakened regulatory oversight and uneven benefit distribution. Quarrying has been linked to economic development, particularly in impoverished regions of the continent, but it has also contributed to environmental complications such as soil degradation, chemical contamination, and air pollution [

8].

In Lesotho, mining and quarrying activities are the backbone of the country's economy [

9]. However, the Government of Lesotho reported that the mining and mineral sector remains at a nascent stage, and although the sector is dominated by diamond mining, sandstone and dolerite mining are on the rise [

10]. The report further shows that the sector’s contribution to Gross Domestic Product hovered around eight % between 2012 and 2018. The industry's revenue grew from twenty-eight million dollars in 2013 to forty-seven million dollars in 2018, with certain years registering over fifty-seven million dollars [

10,

11]. Despite this growth, the artisanal and small-scale mining sector remains underdeveloped, with muddled guidelines and no legal framework to guide mining prospects [

10].

Moreover, despite the economic benefits, there is growing concern about the socio-economic impacts of quarrying activities on local communities [

7,

12,

13]. Quarrying activities have both positive and negative impacts on the standard of living of local communities and the economy at large [

13,

14]. The positive impacts include job creation and business opportunities, leading to improved income levels and access to better living conditions [

2,

7,

14]. However, quarrying also results in environmental degradation, dust pollution, soil erosion, and groundwater contamination, which can significantly affect agricultural productivity and community health, especially in areas closest to the quarry site [

6,

15,

16]. Although there is extensive literature on the impacts of large-scale mining in Sub-Saharan Africa [

17,

18,

19], studies focusing on the socio-economic and spatial effects of small-scale quarrying remain limited, especially in landlocked countries like Lesotho. While existing literature often generalises the impacts of extraction, this overlooks the spatial inequalities that arise. Households closest to quarries may gain employment but also face disproportionate environmental burdens, such as dust exposure and land degradation. So, by applying a mixed-methods approach across five buffer zones ranging from zero to one thousand m from the formal quarry site, this paper explores how quarrying influences household income, employment opportunities, livelihoods, health, and access to essential resources.

This study draws on the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) and Sustainable Development Theory (SDT) to analyse the socio-economic dynamics of quarrying. SLF helps evaluate the impact of quarrying on key livelihood assets, namely: natural, human, social, financial, and physical capital [

20]. However, SLF has been critiqued for its static approach to sustainability, especially in rapidly changing environmental and economic contexts [

21,

22]. SDT complements this by considering how economic activities align with long-term environmental stewardship, equity, and institutional stability. Together, these frameworks offer a holistic lens through which to assess how sandstone quarrying reshapes livelihoods in Lekokoaneng. It also contributes to addressing the gap in the literature by providing disaggregated data across buffer zones and exploring community-level experiences within a localized but policy-relevant context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study is focused in Lekokoaneng in the Berea district of Lesotho. The Berea district is home to Lekokoaneng village, which is approximately forty kilometers away from Maseru. The sandstone formations in Lesotho are linked to the Karoo Supergroup, dating back to the late Carboniferous to early Jurassic periods, and they are primarily represented by the Clarens Formation, embedded in the Stormberg Group [

23,

24,

25]. These formations significantly influence groundwater storage as they impact runoff and infiltration [

25,

26]. The geological structure of the region affects the movement and availability of groundwater, with variations observed in permeability based on the presence of dykes [

23,

27]. In Lesotho, dykes wider than fifty meters contain massive gabbro below a depth of one meter, making them impermeable and acting as barriers to groundwater flow [

25]. Many dykes' ranges between two and twenty m in width, composed of basalts and dolerites, and are often fractured to depths of twenty to forty m, leading to higher permeability compared to surrounding areas [

25,

27]. Though the primary focus is on Lekokoaneng, the broader description of the Berea district provides necessary context for understanding the study area.

2.2. Data Sources and Methods

The study employed a mixed-methods approach to generate both qualitative and quantitative insights from a purposive sample of two hundred and three community members drawn from a population of two thousand and thirty-two residents across five buffer zones. Population data were obtained directly from the Bureau of Statistics, Lesotho. Structured questionnaires, comprising both open and closed-ended questions, were administered alongside field observations to capture direct community experiences on the socio-economic impacts of sandstone quarrying, including household income, employment opportunities, environmental concerns, and health risks. Kobo Toolbox, an open-source software for digital data management and analysis, was used to facilitate survey design and data collection. Participants were selected through a stratified random sampling technique to ensure responses reflected varying distances from the quarry site.

Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis, which involved familiarisation, coding, generation of categories, reviewing themes, and defining and naming themes [

28]. The themes were further categorised into sub-themes and transformed into quantifiable variables, allowing for frequency and percentage distribution analysis across buffer zones. This integration of qualitative depth with quantitative rigor strengthened the validity and applicability of the findings. To further interpret the socio-economic impacts, the study employed the Sustainable Livelihood Framework [

20] to examine how quarrying affects the five key assets: human, social, natural, physical, and financial, while the Sustainable Development Theory provided a lens for assessing long-term socio-economic and environmental sustainability.

The stratified random sampling formula used to determine proportional representation across buffer zones is as follows. The formula is expressed as Equation 1 as expressed below:

Where:

= the number of sampled households in stratum (each buffer zone)

N= the total number of households in stratum,

N= the total population of households (2032), and

n = the overall sample size.

The total sample size of n=203 was determined by applying a proportion of approximately 10% of the overall population. At a 95% confidence level and assuming a maximum variability of p=0.5, a sample of approximately 203 households yields a margin of error of about ±6.5%. This aligns with Yamane’s (1967) simplified formula for finite populations and is expressed as Equation 2: (n=N/ (1+Ne)), which produces a comparable result when N=2032 and e≈0.066.

3. Results

3.1. Household Income Impact

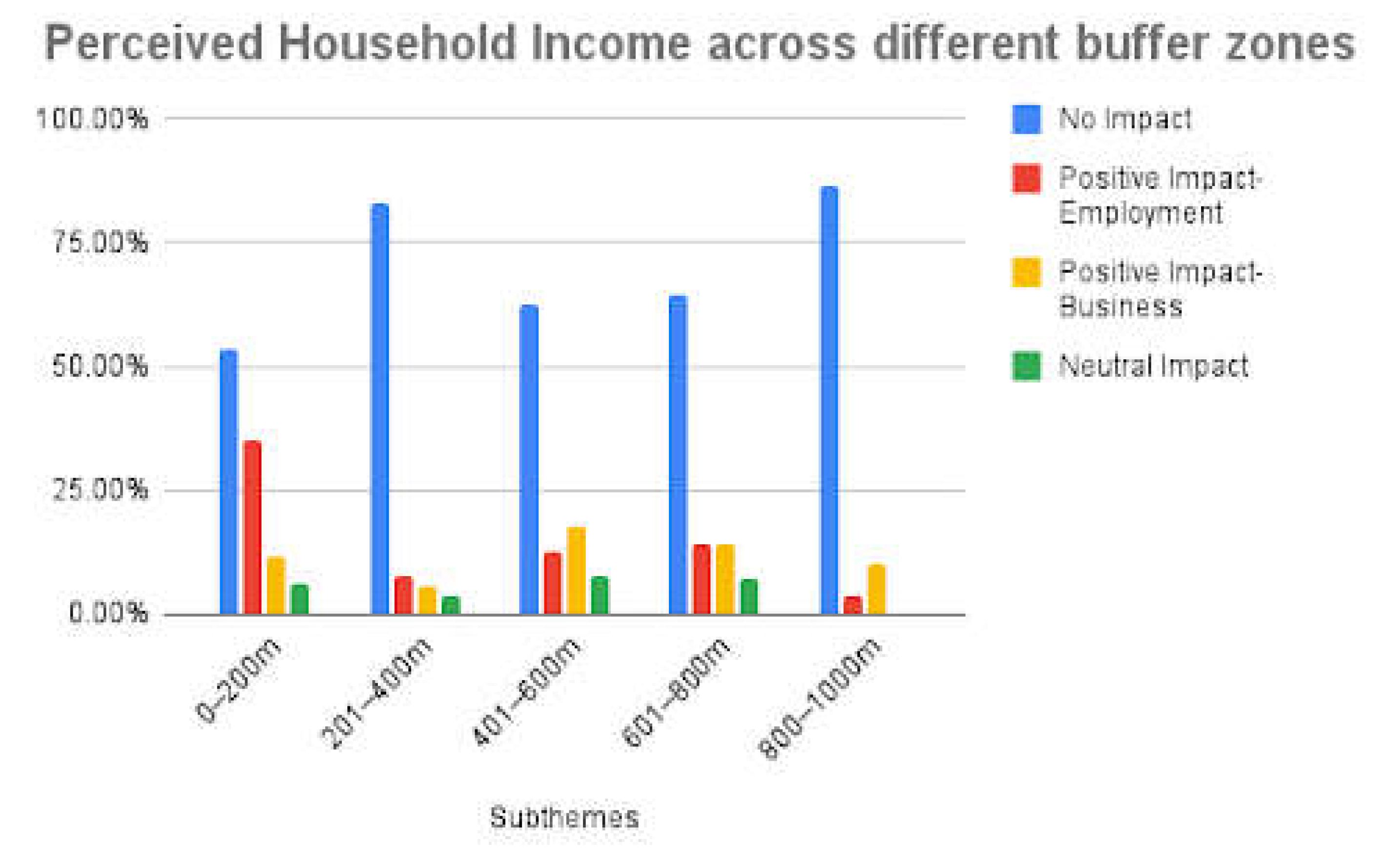

The study classified the impact of sandstone quarrying on household income into four themes: no impact, positive impact through employment, positive impact through business operations, and neutral impact where quarrying had limited influence (

Figure 1). Responses varied across buffer zones. The 0–200-meter buffer zone recorded 35 % positive impact from employment and 11.7 % from businesses, showing that quarrying strongly supports income generation in areas closest to extraction sites. Middle buffer zones of 401–600 m and 601–800 m recorded positive impacts ranging from 12.5 to 17.5 %, reflecting informal quarrying activities. However, households farther from the quarry site reported little to no impact.

In summary, out of all the households surveyed in the area, an estimated 47% to 59% reported that sandstone quarrying had a direct or indirect positive impact on their income, either through full-time employment at quarry sites or from operating small businesses nearby. These impacts were mostly found in the closest and middle buffer zones, where quarry activities-both legal and illegal- are found. In comparison, households in outer zones reported minimal to no income benefits from quarrying, relying instead on alternative livelihoods such as subsistence farming or informal trade. To quantify the study of the household income impact in any buffer zone, a formula (Equation 2) was generated to determine the gradient of economic impact as one move away from the quarry site.

Where: Iq = Average income from quarrying per household

Pe = Proportion of households employed in quarrying

Ae = Average income from employment

Pb = Proportion of households generating income through quarry-related

business

Ab = Average monthly income from business related to quarrying

The positive impact range per buffer zone reported in the study reflects variations in survey responses across zones, informal vs formal employment, temporal differences, and gender or age-based household roles.

This is expressed in Equation 3 as:

Where: Pt = Percentage of households with positive income impact

Hp = Number of households with positive impact

Ht = Total number of surveyed households

3.2. Employment Opportunities

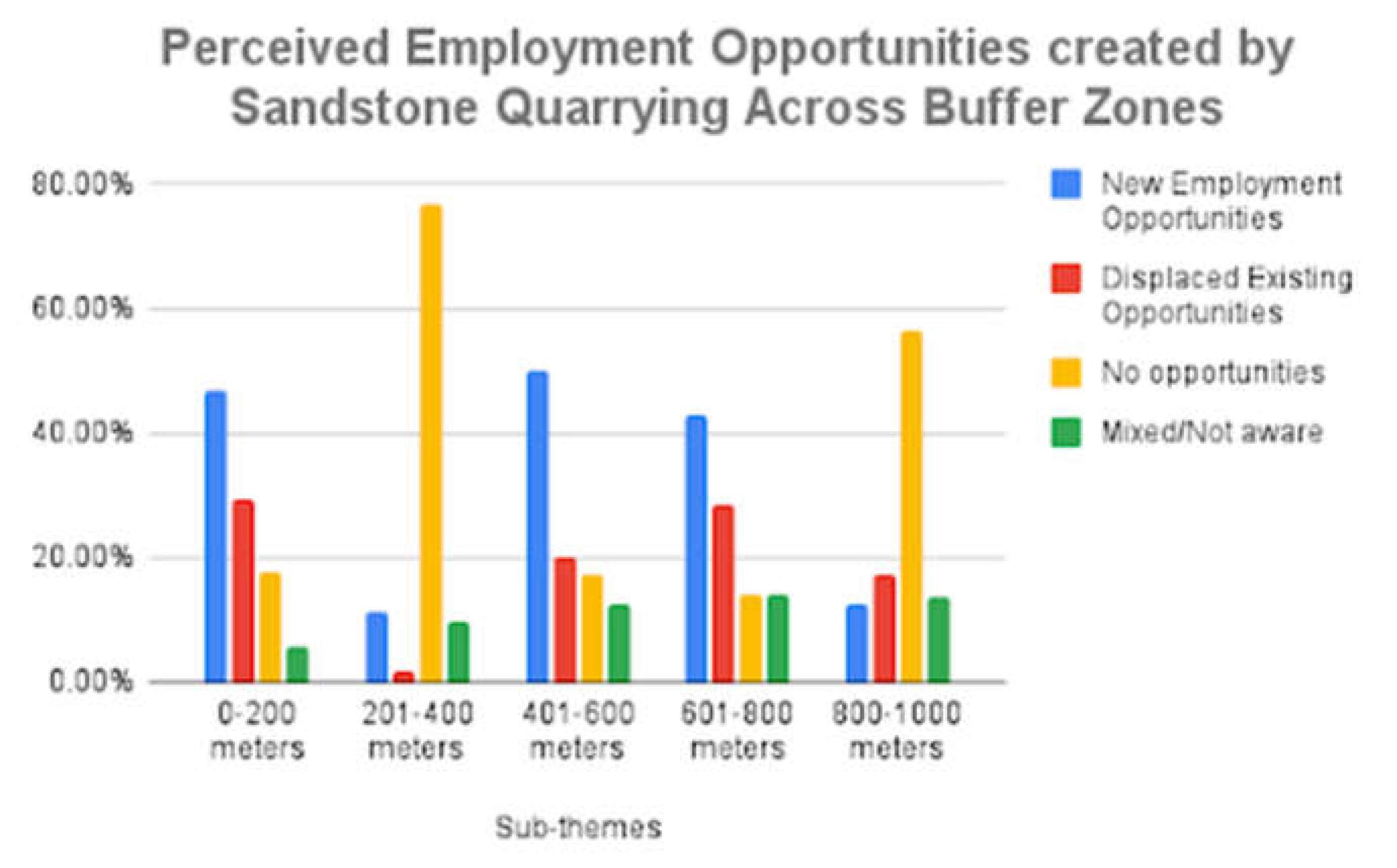

Employment opportunities created by quarrying were categorized into new employment, displaced employment, no opportunities, and mixed responses (

Figure 2). The 0–200-meter buffer zone recorded the highest employment impact at 47 percent, showing direct job creation. Middle buffer zones 401–600 meters and 601–800 meters recorded employment opportunities between 42.8 and 50 percent, demonstrating quarrying’s role in labor markets. However, 29.4 percent of respondents in the closest buffer zone noted displaced employment due to quarry expansion. The 201–400 meters and 800–1000 meters zones recorded the lowest employment impact, with 56 to 76.9 percent of respondents stating no direct benefits from quarrying.

In summary, out of all households surveyed, approximately 47% to 50% of households located within 0–600 meters of the quarry reported new employment opportunities created by sandstone quarrying, particularly in zones closer to active extraction sites. However, these benefits were uneven, as up to 29.4% of respondents in the same zones also reported that quarrying had displaced existing jobs or disrupted prior income-generating activities. Notably, zones further from the quarry (201-400 meters and 800-1000 meters) showed limited benefit, with over 56% to 76.9% of respondents indicating no significant employment impact. These findings suggest that proximity to the quarry strongly influences employment outcomes, creating opportunities for some while displacing others or leaving many unaffected.

To quantitatively assess employment effects per zone, the Employment Opportunity Index (EOI) as proposed by [

29] was used. The Employment Opportunity Index (EOI) is a multidimensional measure of job market perceptions based on both positive (job creation) and negative (job displacement or exclusion). This theorem is expressed in the equation below (Equation 4).

Where: Pn = Proportion of households or respondents reporting new employment

opportunities due to quarrying.

Pd = Proportion of households or respondents reporting displacement from

previous employment because of quarry operations.

A positive EOI value indicates that quarrying generates net employment gains, whereas a negative value reflects situations where job losses outweigh opportunities, highlighting displacement as the dominant outcome.

3.3 Livelihood Impact

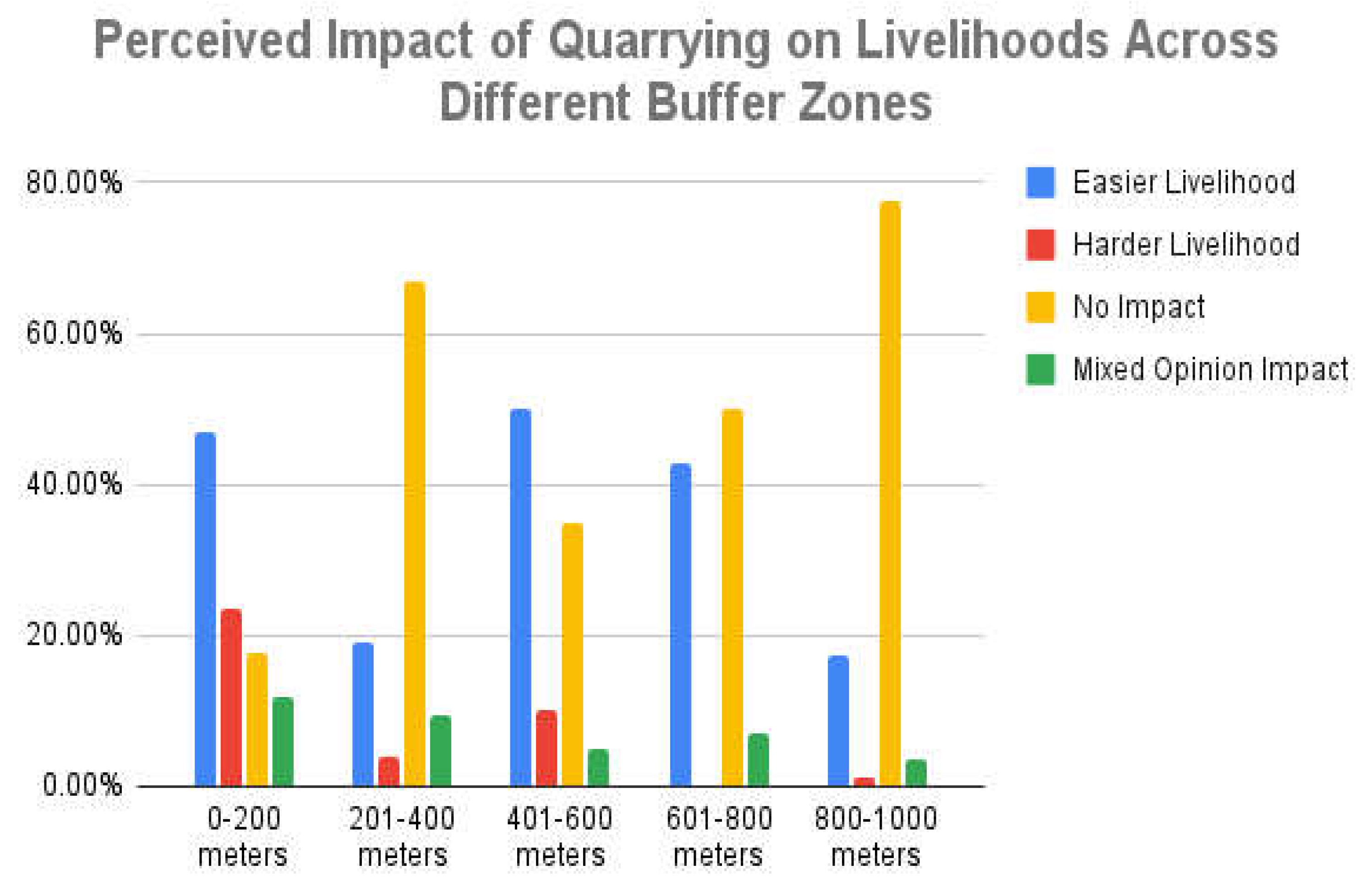

The livelihood impact of quarrying was examined across four themes: easier livelihoods, harder livelihoods, no impact, and mixed responses (

Figure 3). The 0–200-meter buffer zone reported 47 percent of respondents indicating easier livelihoods, due to quarry-related income opportunities. Similarly, 50 percent of respondents in the 401–600-meter zone reported livelihood improvements. However, 23.5 percent of respondents in the closest buffer zone noted that quarrying had made their livelihoods harder, primarily due to environmental degradation affecting agricultural productivity. The 801–1000-meter buffer zone recorded 77.5 percent of respondents indicating no impact, demonstrating that socio-economic benefits diminish with distance.

In all surveyed households across different buffer zones, the closest buffer zone (0-200 meters) reported the most significant improvement in livelihoods, with 47 of respondents indicating that sandstone quarrying had made life easier through increased income and related opportunities. Similarly, 50% of those in the 401–600-meter zone also reported easier livelihoods. However, these improvements were not universal. In the 0–200-meter zone, 23.5% of respondents noted that quarrying had made their livelihoods harder, largely due to environmental degradation and reduced agricultural productivity. The farthest zones (801-1000 meters) showed minimal benefit, with 77.5% of respondents reporting no impact on their livelihoods. These findings suggest that the livelihood benefits of quarrying are spatially uneven, concentrated close to the quarry but diminishing with distance, and offset by emerging environmental and social challenges.

3.4 Access to Water, Food, and Other Resources

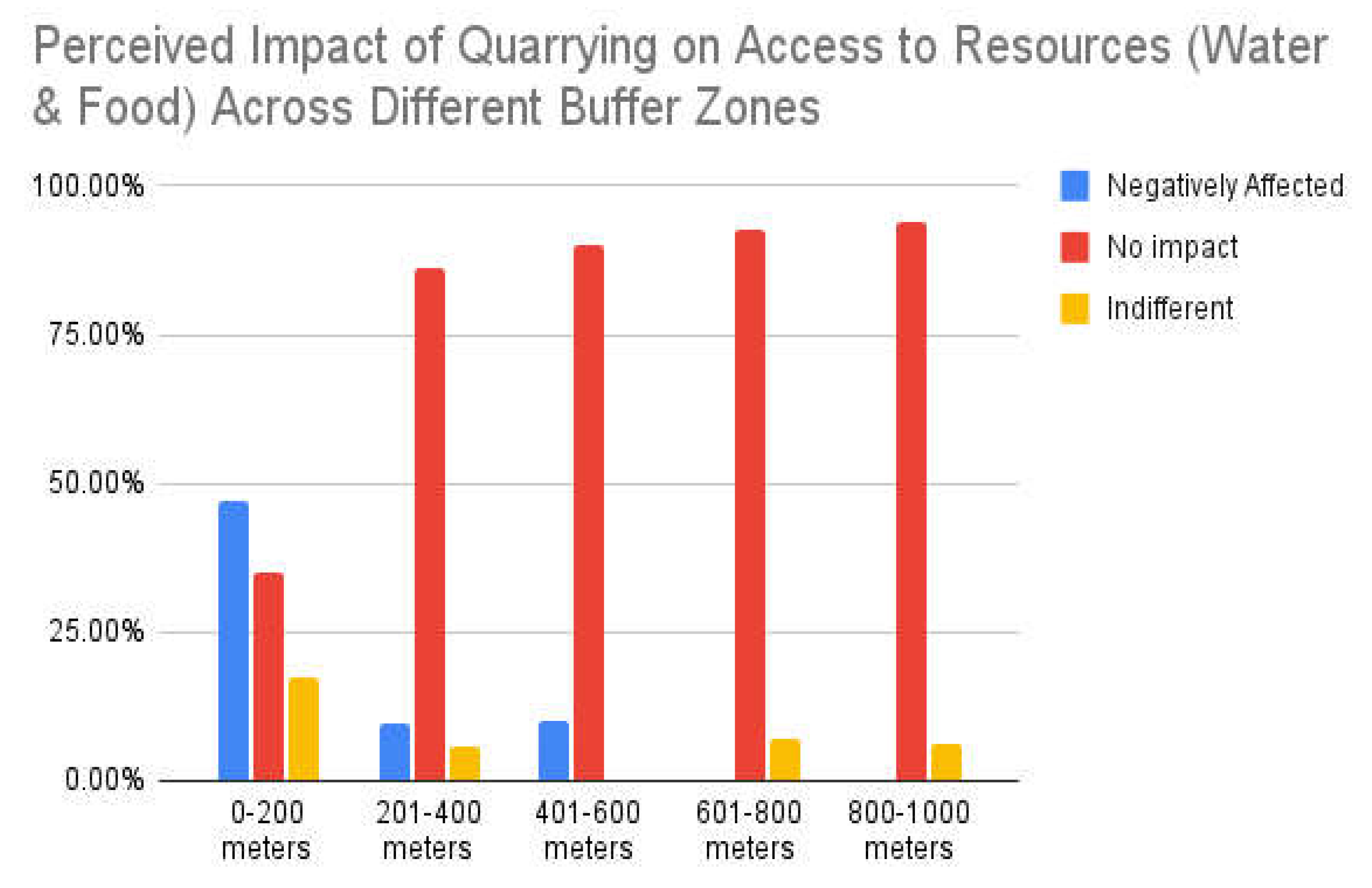

The study assessed the influence of quarrying on access to essential resources, categorizing responses into negatively affected, no impact, and indifferent (

Figure 4). The 0–200-meter buffer zone recorded 47 percent of households experiencing negative impacts, including water contamination, dust pollution, and reduced soil fertility. In contrast, households in the 801–1000-meter zone recorded 93.75 percent indicating no impact, reinforcing that environmental risks are concentrated near the quarry.

The survey findings reveal that the impact of sandstone quarrying on access to water, food, and other essential resources is highly localized. In the closest buffer zone (0–200 meters), 47% of respondents reported negative effects, primarily due to environmental degradation, including dust pollution, water contamination, and reduced land suitability for food production. In contrast, the farthest zone (801–1000 meters) reported minimal disruption, with 93.75% of households indicating no impact on their access to resources. These results suggest that proximity to quarrying activities directly influences household vulnerability to resource access constraints, highlighting the need for targeted environmental management and mitigation strategies in communities closest to extraction sites.

3.5. Health Impact and Medical Attention

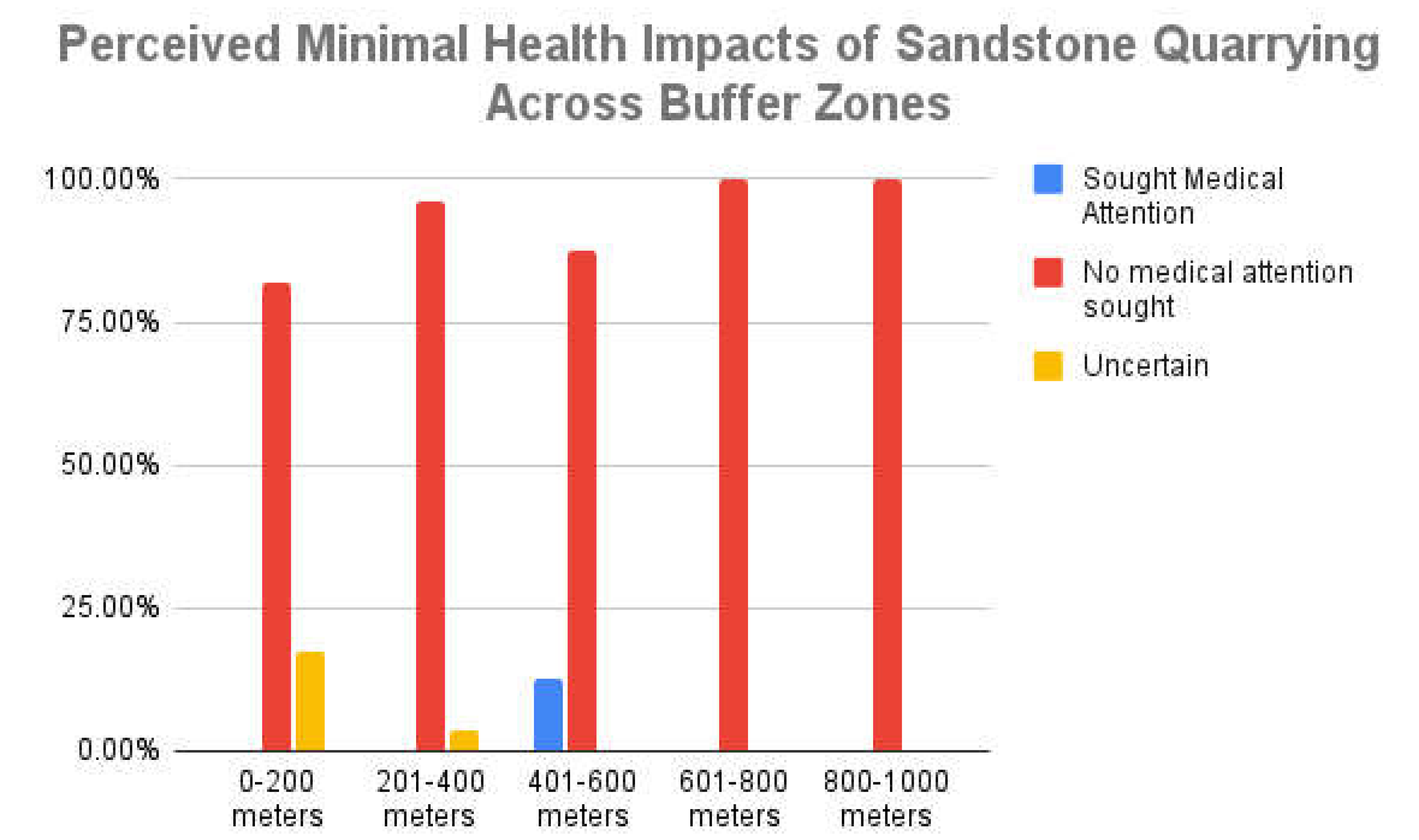

Health effects were categorized into sought medical attention, no medical attention, and uncertain responses (

Figure 5). The 401–600-meter buffer zone recorded 12.5 percent of respondents seeking medical attention, for respiratory issues linked to dust exposure. The 0–400-meter zones reported uncertainty, suggesting underreporting or a lack of formal health assessments. The 601–800-meter and 801–1000-meter zones recorded 100 percent, stating no medical attention sought, indicating lower perceived health risks in distant areas.

Perceptions of health impacts from sandstone quarrying appear to be limited and similar. Across all buffer zones, most respondents reported no need to seek medical attention, with the 601–800 meter and 801–1000-meter zones recording 100% under this theme. However, 12.5% of respondents in the 401–600-meter zone reported having sought medical attention due to quarry-related conditions, while some households in the 0–400-meter zones expressed uncertainty about the link between quarrying and their health status. These findings suggest that while quarrying-related health concerns are not widely reported, possible underreporting or lack of formal diagnosis may obscure the true extent of health impacts, particularly in closer zones. The data highlights the need for community health education and regular environmental health assessments in quarry-affected areas to better understand and manage potential health risks.

3.6. Health and Safety Concerns

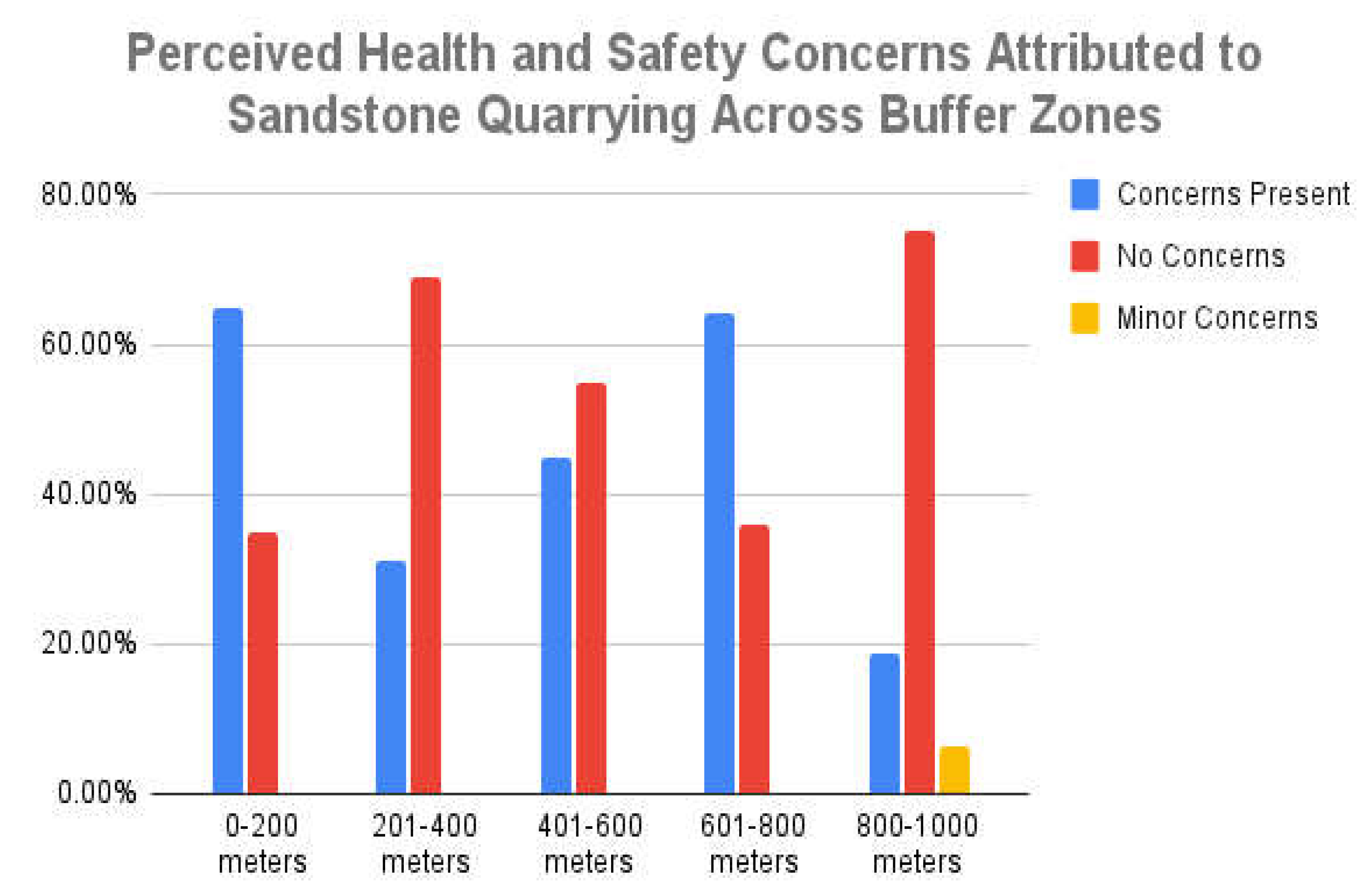

Community concerns regarding health and safety risks were categorized into concerns present, no concerns, and minor concerns (

Figure 6). The 0–200-meter buffer zone recorded 64.7 percent of respondents expressing serious concerns, particularly dust-related illnesses, and water contamination risks. Similarly, 64 percent of respondents in the 601–800-meter buffer zone reported safety concerns. The 201–400 meter and 801–1000-meter zones recorded fewer concerns, with 69 percent and 75 percent of respondents stating no significant issues. Only 6.25 percent of respondents in the farthest zone reported minor concerns, primarily speculative health risks.

In summary, out of the respondents surveyed, 64.7% in the 0–200-meter buffer zone and 64% in the 601–800-meter zone expressed clear health and safety concerns related to quarrying, such as dust-related illnesses like tuberculosis and potential waterborne diseases due to contamination. In contrast, “No Concerns” dominated the 201–400-meter (69%) and 801–1000-meter (75%) zones, suggesting that perceptions of risk decrease with distance from the quarry. Only 6.25% in the farthest zone (801-1000 meters) expressed minor, speculative concerns. These findings reveal that proximity to quarrying activity strongly influences health and safety perceptions, underlining the importance of targeted health interventions and risk communication strategies for communities closest to the quarry sites.

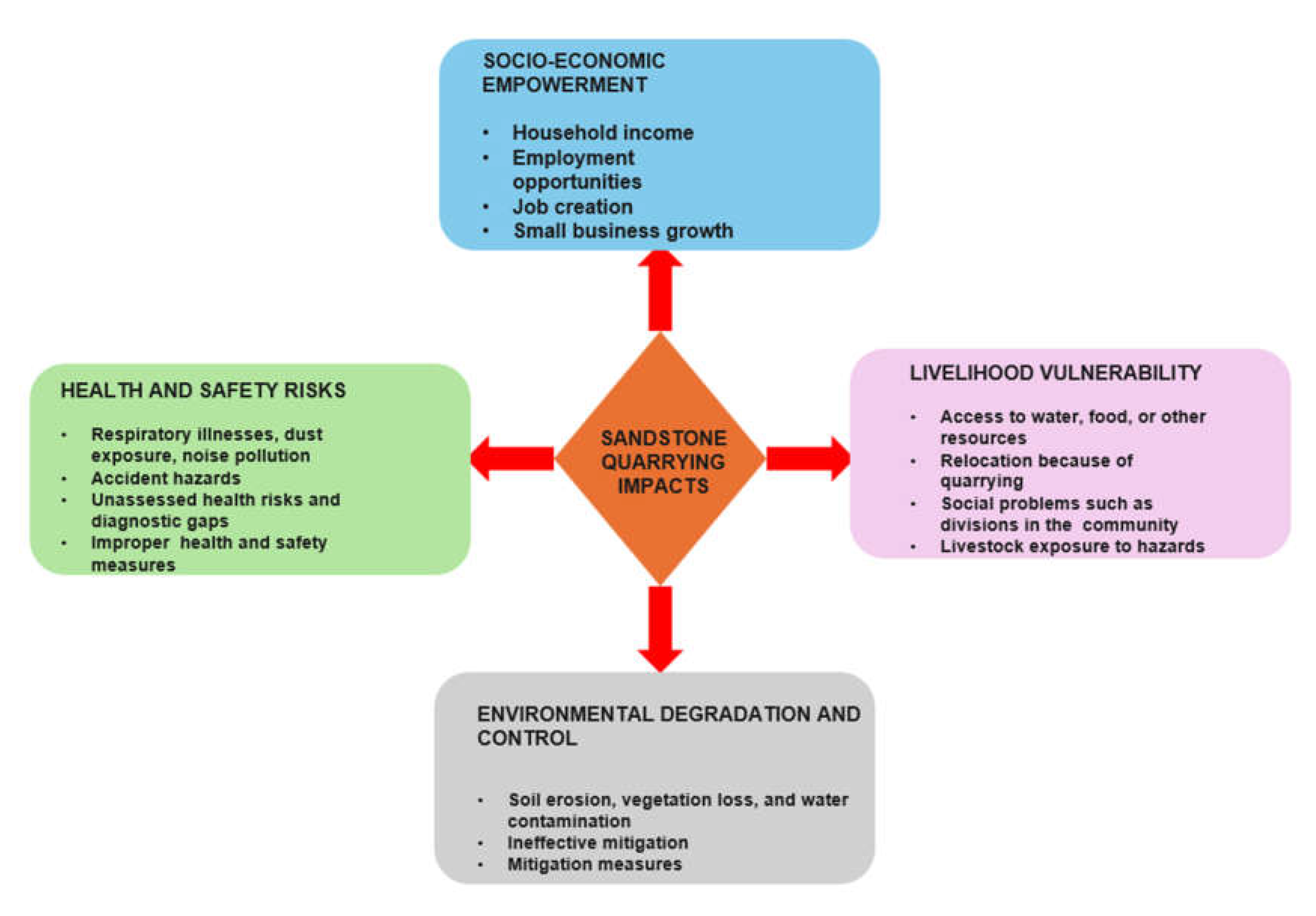

3.7. Thematic Analysis

A qualitative approach was used in this study to gather information about participants' understandings of the economic impact of sandstone quarrying in Lekokoaneng, Lesotho, and meanings attached to their encounter with it, through thematic analysis. [

28] formulated a six-phase guide, which is a very useful framework for conducting this kind of analysis. In this study, thematic analysis was used to analyse the interview responses from the perspectives of familiarisation, coding, generating categories, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, to writing up the results. The results obtained contained the following four themes: Socio-Economic Empowerment, highlighting job creation and household income variety; Livelihood Vulnerability, reflecting reduced agricultural productivity and relocation because of quarrying; Health and Safety Risks, including respiratory illnesses, dust exposure, and accident hazards; and Environmental Degradation and Control, covering soil erosion, vegetation loss, water contamination, and ineffective mitigation measures (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

Quarrying is widely recognised as a twofold activity, offering economic opportunities while simultaneously causing significant environmental and social challenges. In most developing countries, it serves as a critical source of employment, livelihood support, and local economic growth, yet these benefits often come with environmental degradation and health risks (8,13). Thus, it is imperative to look at the importance of adopting a framework which will not only look at the economic contributions but also the environmental costs and social well-being of people.

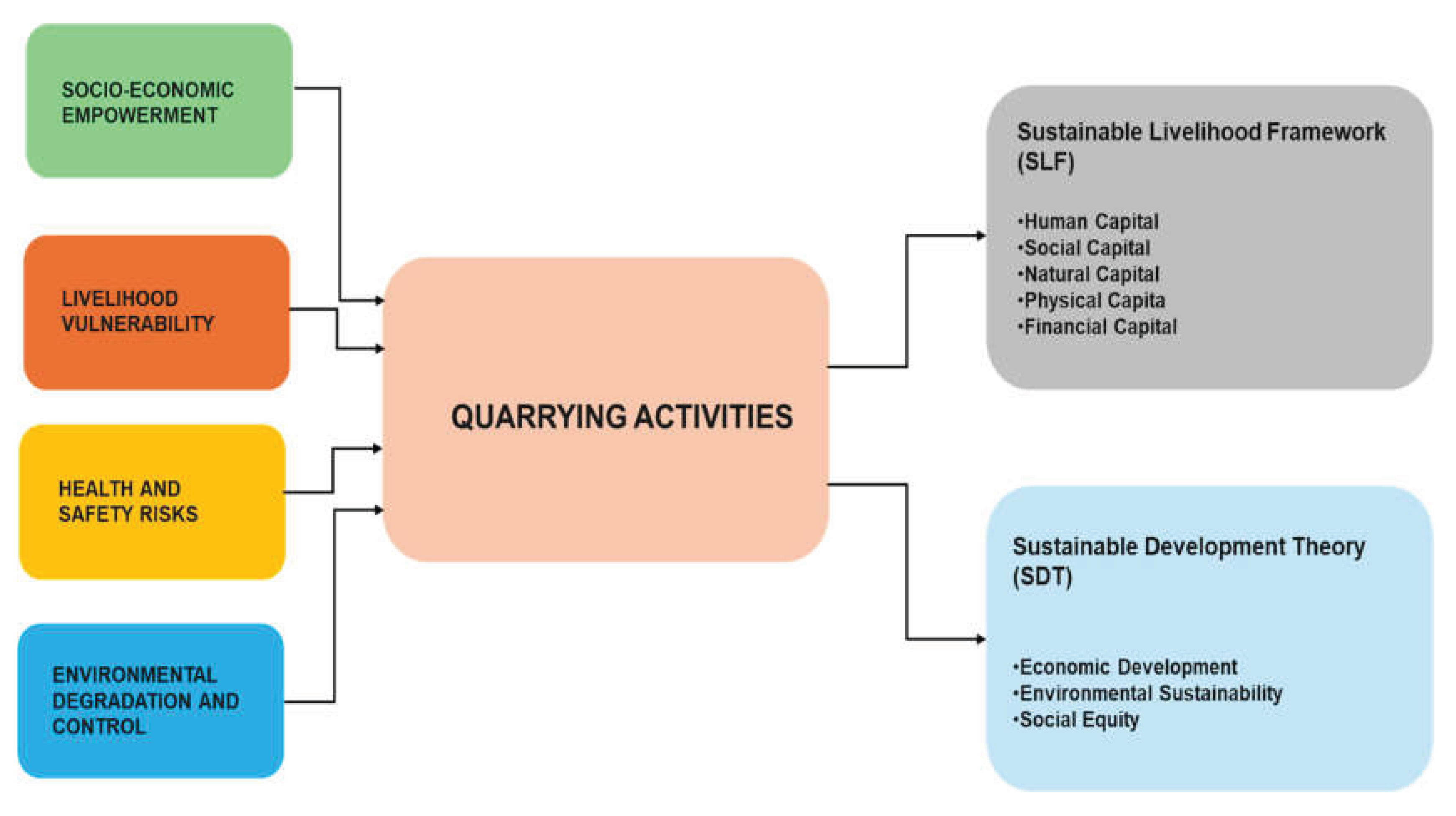

In this study the use of Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) and Sustainable Development Theory (SDT) provided a holistic analysis of the environmental and socio-economic dynamics of sandstone quarrying in Lekokoaneng. The SLF highlights the role of human capital, social capital, natural capital, financial capital and physical capital in creating livelihood outcomes, while SDT offers a framework of understanding development processes in terms of social, environmental and economic aspects. By linking quarrying impacts to these frameworks, the thematic analysis was used to show the coordinated nature of economic empowerment, environmental degradation, livelihood vulnerability, and health and safety concerns.

The framework puts quarrying at the centre of a network of interrelated outcomes, showing how its benefits and challenges intersect across the dimensions of SLF and SDT (

Figure 8).

The thematic framework developed in this study (

Figure 8) positions quarrying at the centre of a network of interrelated outcomes, demonstrating how its benefits and challenges intersect across livelihood capitals and sustainability dimensions. For example, employment opportunities may temporarily empower households, but informal, seasonal work fails to generate lasting skills, leaving human capital fragile. Similarly, small business activities flourish around the quarry, but illegal operations and disputes in mid-range buffer zones weaken social cohesion, reflecting an erosion of social capital. Environmental degradation compounds these vulnerabilities, undermining natural capital through water scarcity, dust, and soil fertility loss, which in turn reduces agricultural productivity and food security. Infrastructure deficits, such as poor access roads, further show how physical capital remains neglected despite the quarry’s economic contribution. These interconnections illustrate how empowerment and vulnerability are not isolated but occur simultaneously, reinforcing one another in ways that shape household resilience.

By integrating quantitative indicators such as the Income Gradient and Employment Opportunity Index with qualitative insights from thematic analysis, the study highlights how quarrying is more than an economic driver, it is a livelihood system marked by trade-offs. Financial gains are concentrated close to the quarry, but so are the steepest environmental costs. Households in outer buffer zones (801–1000m) experience fewer risks but also miss out on economic opportunities, underscoring the spatial inequalities embedded in extractive economies [

19]. These findings align with [

21] critique of livelihood strategies as “sustainability trade-offs,” where immediate gains mask long-term vulnerabilities.

In this sense,

Figure 8 is not merely a schematic but a representation of how quarrying shapes livelihoods in Lekokoaneng: as a nexus of economic empowerment, vulnerability, degradation, and risk. It captures the dynamic interplay between SLF capitals and SDT principles, making visible the contradictions of quarry-led development. The challenge, therefore, is not simply whether quarrying brings benefits, but whether those benefits can be structured in ways that do not erode the ecological and social foundations of community resilience. In the absence of deliberate interventions such as environmental safeguards, institutional oversight, and reinvestment in infrastructure, quarrying risks entrenching cycles of fragility rather than fostering sustainable livelihoods.

5. Conclusions

The socio-economic impacts of sandstone quarrying in Lekokoaneng reveal a complex interplay between livelihood opportunities and sustainability challenges. Quarrying generates direct income and employment, particularly within the 0–600m buffer zones, while also stimulating small business activities that contribute to local economic empowerment. However, these benefits are unstable, largely informal, and concentrated in areas most exposed to severe environmental degradation, including dust pollution, water contamination, and soil fertility loss.

By applying the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) and Sustainable Development Theory (SDT), the study demonstrates how quarrying simultaneously enhances financial capital and undermines natural, social, and human assets, thereby weakening long-term livelihood resilience. The thematic analysis further underscores this duality, with empowerment coexisting alongside vulnerability and environmental decline. Quarrying in Lekokoaneng thus reflects a “double-edged” development pathway, where short-term gains are offset by long-term risks to sustainability.

To realign quarrying with sustainable development, stronger institutional oversight, community-inclusive governance, and corporate reinvestment in physical and social infrastructure are essential. Environmental safeguards must be prioritised to mitigate dust, water, and soil impacts; while formalising employment can strengthen financial and human capital. Without such measures, quarrying risks locking communities into fragile livelihoods that compromise intergenerational equity and broader progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

Ultimately, the Lekokoaneng case illustrates the need for policies that balance extraction with stewardship, therefore transforming quarrying from a narrow economic driver into a platform for resilient and sustainable community development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and N.M.; methodology, L.M. and N.M.; formal analysis, L.M.; investigation, L.M; validation, L.M and N.M; resources, L.M, and N.M.; data curation, L.M.; software, L.M.; writing-original draft preparation, L.M.; writing-review and editing, L.M and N.M.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, N.M.; project administration, L.M. and N.M. funding acquisition, L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Government of Lesotho through the National Manpower Development Secretariat (NMDS). Grant Number: 202321000128

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical considerations.

Acknowledgments

All participants who generously shared their time and experiences for this research are fully acknowledged. Full responsibility for the final content and its scholarly contributions is taken. Gratitude is also extended to the Bureau of Statistics Lesotho for providing essential statistical data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

SLF

SDT |

Sustainable Livelihood Framework

Sustainable Development Theory |

References

- Ankomah Baffour. The Africa factbook : busting the myths. African Union; 2020. 1124 p.

- Legwaila IA, Lange E, Cripps J. QUARRY RECLAMATION IN ENGLAND: A REVIEW OF TECHNIQUES. Journal American Society of Mining and Reclamation. 2015 Oct 3;55–79.

- Nartey VK, Nanor JN, Klake RK. Effects of Quarry Activities on some Selected Communities in the Lower Manya Krobo District of the Eastern Region of Ghana. Atmospheric and Climate Sciences. 2012;02(03):362–72.

- Umar J, Oriri O. Environmental Effect of Quarry Site on the Adjoining Neighborhood in Oluyole Local Government, Oyo State, Nigeria. Ghana Journal of Geography. 2023 Dec 1;15(3):223–57.

- Akanwa AO, Okeke FI, Nnodu VC, Iortyom ET. Quarrying and its effect on vegetation cover for a sustainable development using high-resolution satellite image and GIS. Environ Earth Sci. 2017 Jul 25;76(14):505.

- Kafu-Quvane B, Mlaba S. Assessing the Impact of Quarrying as an Environmental Ethic Crisis: A Case Study of Limestone Mining in a Rural Community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Apr 1;21(4).

- Twerefou K. Daniel. Mineral exploitation, environmental sustainability and sustainable development in EAC, SADC and ECOWAS. 2009 Jan.

- Hilson Gary. Small-Scale Mining in Africa: Tackling Pressing Environmental Problems With Improved Strategy. J Environ Dev. 2002;11(2):149–72.

- Afrobarometer. Basotho want environmental protection but prioritise jobs. Maseru; 2022 Jun.

- Government of Lesotho. National Strategic Development Plan II 2018/19 - 2022/23: In Pursuit of Economic and Institutional Transformation for Private Sector-led Jobs and Inclusive Growth. Maseru; 2018.

- Lesotho Chamber of Mines. 2022 Lesotho Diamond Industry Performance Report. 2022.

- Sagoe D Christopher, Tsra Gershon. Uncontrolled Sand Mining and its SocioEnvironmental Implications on Rural Communities in Ghana: A Focus on Gomoa Mpota in the Central Region. International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences. 2016;6(6):31–7.

- Turyahabwe R, Asaba J, Mulabbi A, Osuna C. Environmental and Socio-economic Impact Assessment of Stone Quarrying in Tororo District, Eastern Uganda. East African Journal of Environment and Natural Resources. 2021 Oct 23;4(1):1–14.

- Singhal A, Goel S. Impact of Sandstone Quarrying on the Health of Quarry Workers and Local Residents: A Case Study of Keru, Jodhpur, India. In: Treatment and Disposal of Solid and Hazardous Wastes. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 97–118.

- Oshim F, Chukwuemeka E, Amaefule WA, Ayajuru NC, Amaeful EO, Anumaka CC. Socioeconomic and Environmental Impacts of Quarrying in Nigeria: A Comprehensive Review of Sustainable Quarrying Practices and Innovative Technologies. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2024.

- Tanushree Mahapatra. Environmental, social and health impacts of stone quarrying in Mitrapur panchayat of Balasore district, Odisha. International Journal of Science and Research Archive. 2023 Feb 28;8(1):678–88.

- Banchirigah, SM. Challenges with eradicating illegal mining in Ghana: A perspective from the grassroots. Resources Policy. 2008 Mar;33(1):29–38.

- Campbell, BK. Regulating mining in Africa : for whose benefit? Nordiska Afrikainstitutet; 2004. 89 p.

- Chuhan-Pole P, Dabalen AL, Land BC. Mining in Africa: Are Local Communities Better Off? The World Bank; 2017.

- DFID (The Department for International Development). Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. 1999.

- Scoones, I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. J Peasant Stud. 2009 Jan 7;36(1):171–96.

- Natarajan N, Newsham A, Rigg J, Suhardiman D. A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Dev. 2022 Jul;155:105898.

- Bordy EM, Smith RMH, Choiniere JN, Rubidge BS. Selected Karoo geoheritage sites of palaeontological significance in South Africa and Lesotho. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 2024 Jul 18;543(1):431–46.

- BORDY EM, ERIKSSON P. LITHOSTRATIGRAPHY OF THE ELLIOT FORMATION (KAROO SUPERGROUP), SOUTH AFRICA. South African Journal of Geology. 2015 Sep 11;118(3):311–6.

- Schmitz G, Rooyani F. Lesotho Geology, Geomorphology, Soils. Maseru: Morija Printing Works; 1987.

- Catuneanu O, Wopfner H, Eriksson PG, Cairncross B, Rubidge BS, Smith RMH, et al. The Karoo basins of south-central Africa. Journal of African Earth Sciences. 2005 Oct;43(1–3):211–53.

- Bruce Rubidge, Hancox John, Mason Richard. Waterford Formation in the south-eastern Karoo: Implications for basin development. S Afr J Sci. 2012.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006 Jan 21;3(2):77–101.

- Griffeth RW, Steel RP, Allen DG, Bryan N. Employment Opportunity Index. PsycTESTS Dataset. 2011. Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C.D. Title of the article. Abbreviated Journal Name.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).