Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of ARF Family Genes in R. roxburghii Genome

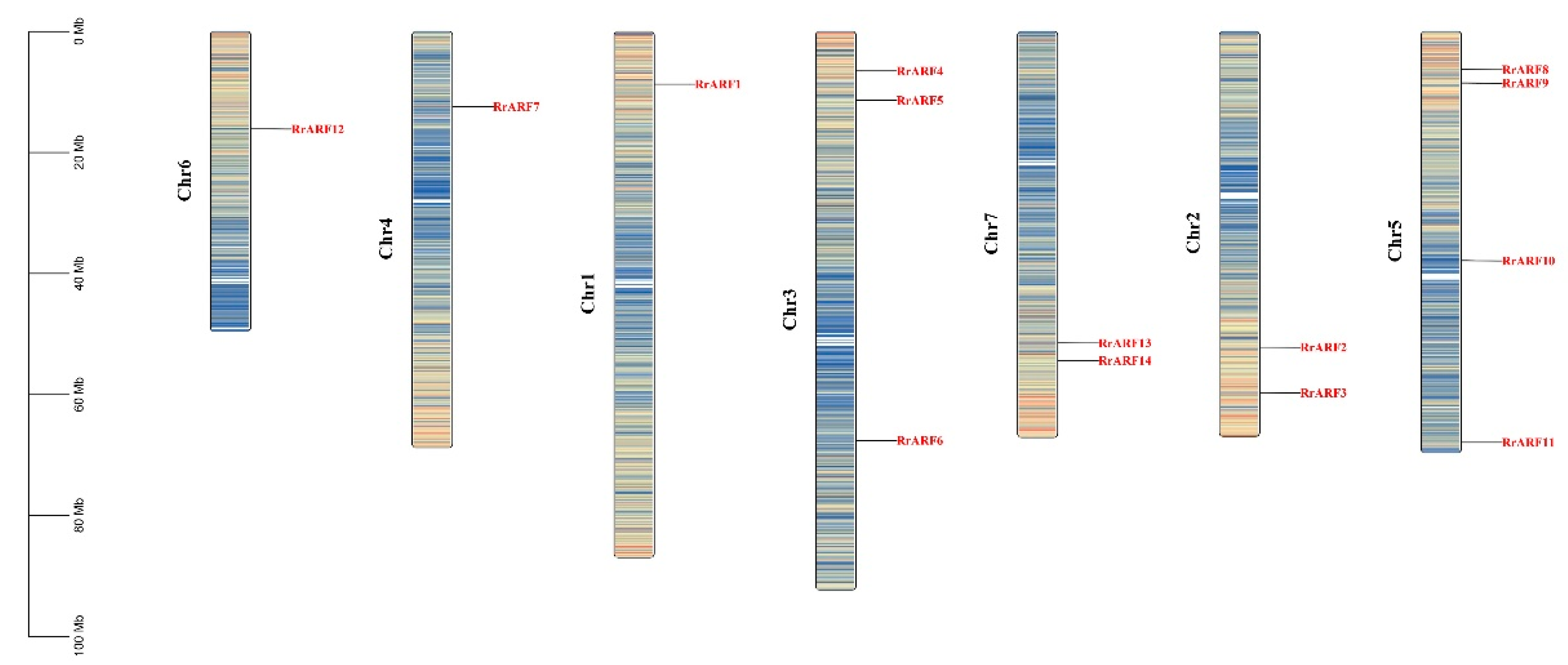

2.2. Chromosomal Distribution of RrARFs

2.3. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in RrARFs Promoters

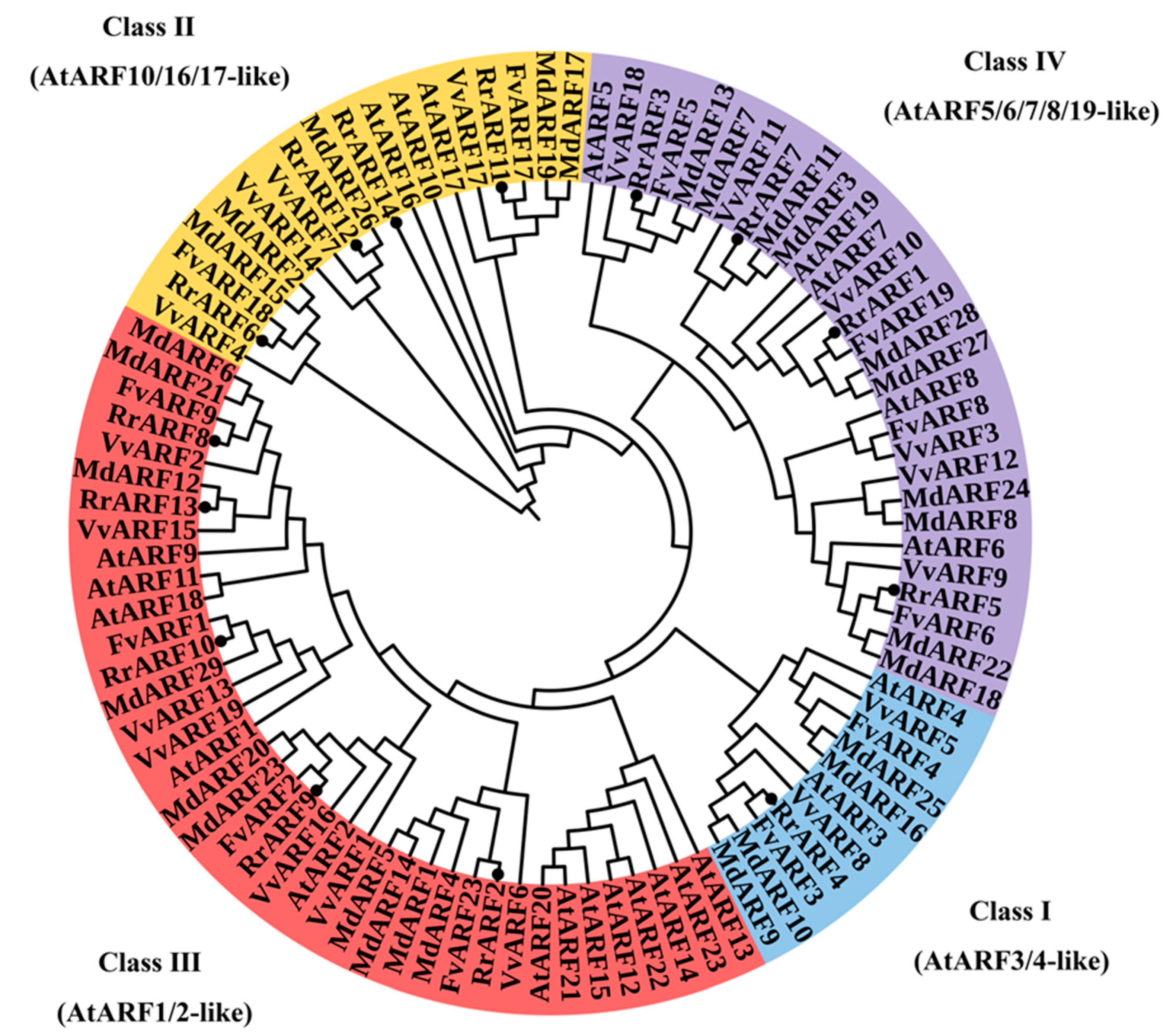

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of the R. roxburghii ARF Gene Family

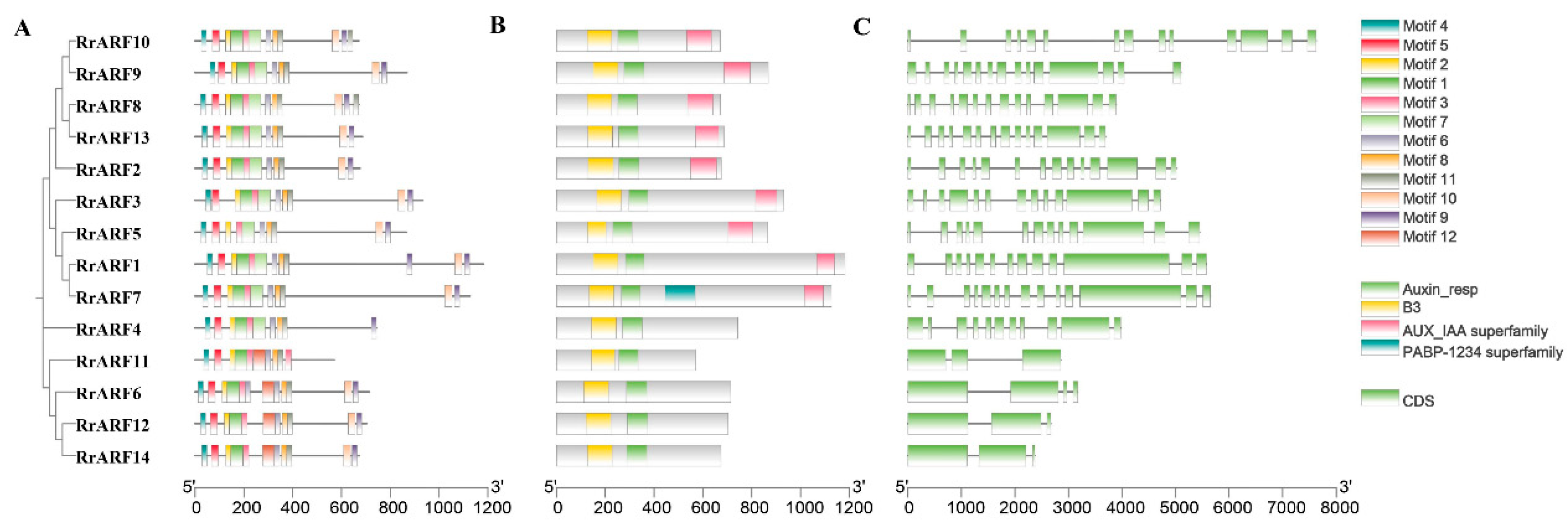

2.5. Gene Structure and Conserved Motifs Characterization

2.6. Gene Expression Analysis of ARF Family Genes

2.7. Weighted Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA)

2.8. Dual-Luciferase (Dual-LUC) Reporter Assay

2.9. Accession Numbers

3. Results

3.1. Identification of ARF Family Genes in R. roxburghii Genome

3.2. Analysis of Conserved Structural Domains and Promoter Sequences of ARF Family Members in R. roxburghii

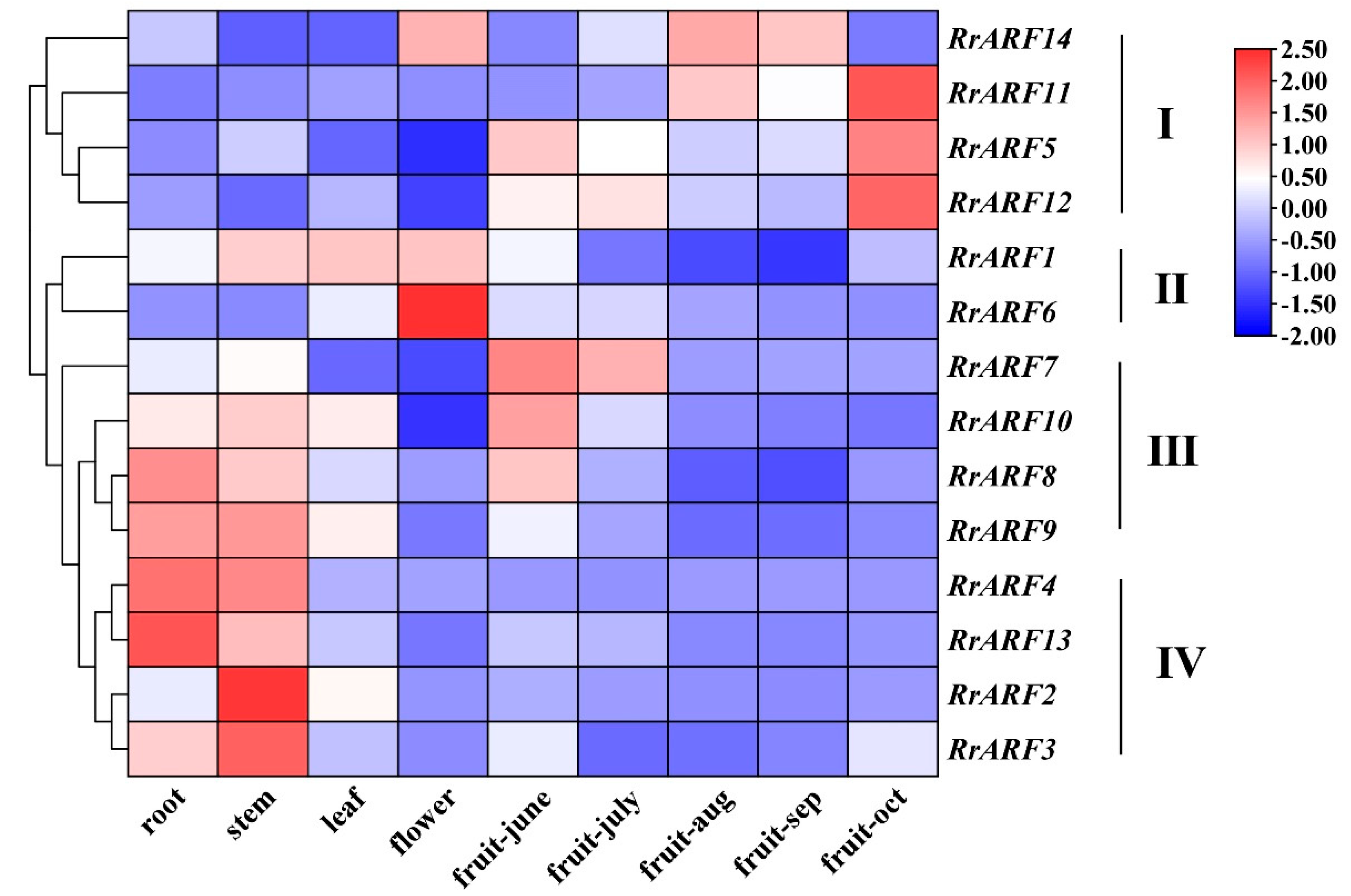

3.3. Expression Profiles of RrARFs in Different Tissues and Developmental Stages

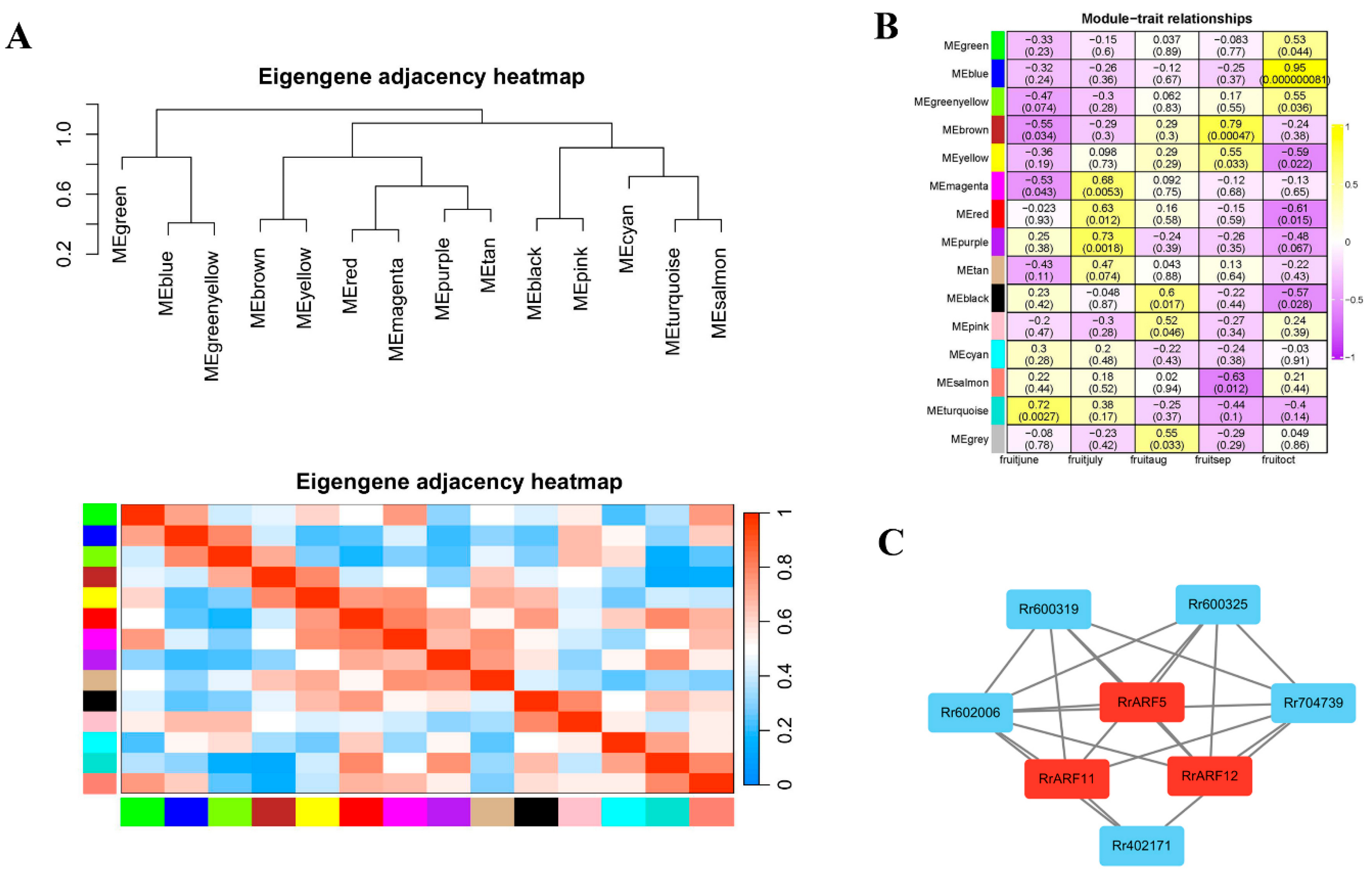

3.4. Co-Expressed Gene Networks of RrARFs

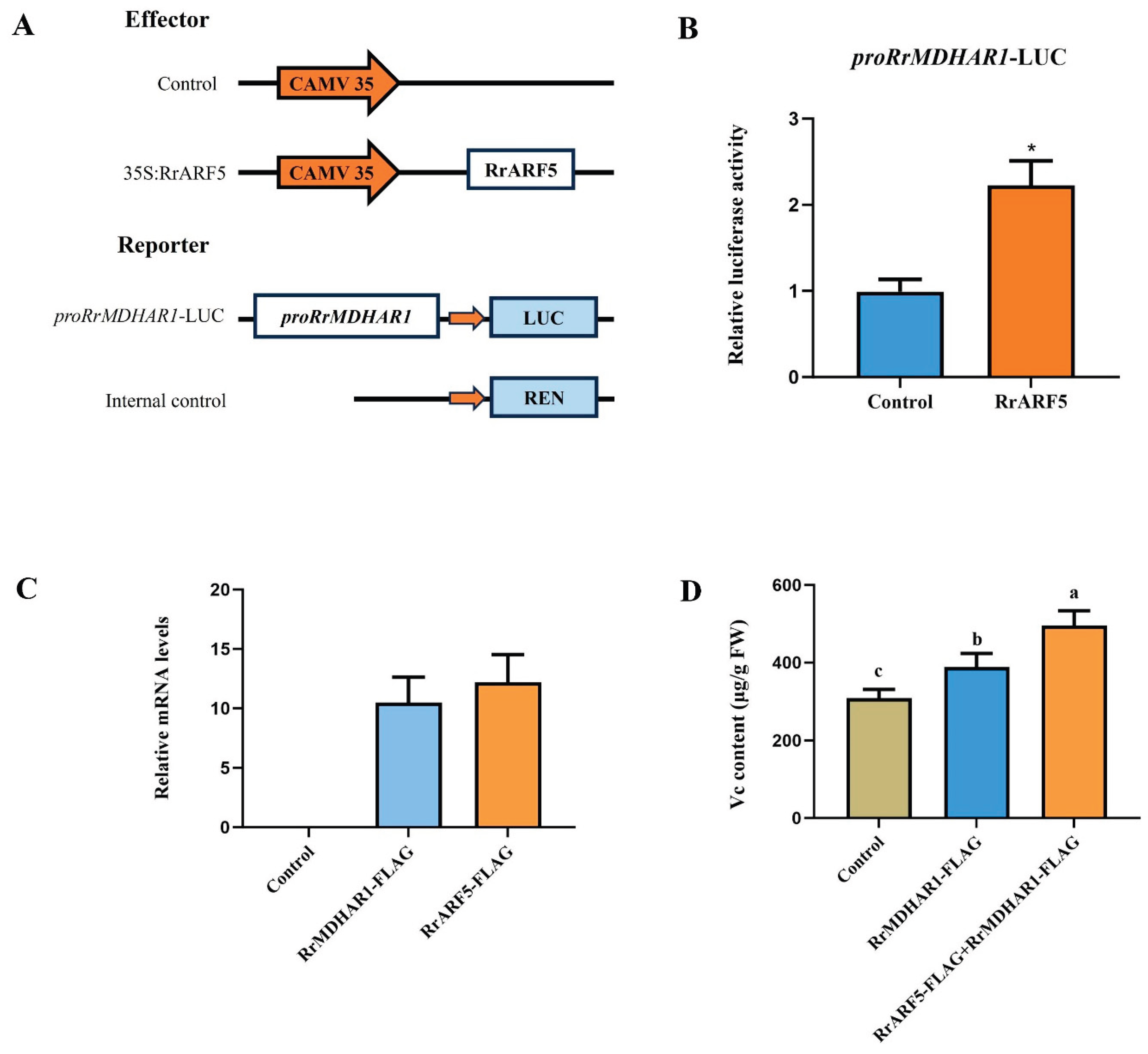

3.5. RrARF5 Involved in VC Biosynthesis by Activating RrMDHAR1 Transcription

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- An, H.; Fan, W.; Chen, L.; Asghar, S.; Liu, Q. Molecular characterisation and expression of L-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase and L-ascorbic acid accumulation during fruit development in Rosa roxburghii. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2007, 82, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Fan, K.; Hu, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, T. Identification and transcriptome data analysis of ARF family genes in five Orchidaceae species. Plant molecular biology 2023, 112, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas Hannah, R.; Frank Margaret, H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Molecular Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weijers, D.; Benkova, E.; Jäger, K.E.; Schlereth, A.; Hamann, T.; Kientz, M.; Wilmoth, J.C.; Reed, J.W.; Jürgens, G. Developmental specificity of auxin response by pairs of ARF and Aux/IAA transcriptional regulators. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 1874–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wu, N.; Fu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, L. A GH3 family member, OsGH3-2, modulates auxin and abscisic acid levels and differentially affects drought and cold tolerance in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 2012, 63, 6467–6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, I.; Sherif Sherif, M.; Jones, B.; Mila, I.; Kumar Prakash, P.; Bouzayen, M.; Jayasankar, S. TIR1-like auxin-receptors are involved in the regulation of plum fruit development. Journal of Experimental Botany 2014, 65, 5205–5215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambhir, P.; Raghuvanshi, U.; Kumar, R.; Sharma Arun, K. Transcriptional regulation of tomato fruit ripening. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2024, 30, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilfoyle Tom, J.; Hagen, G. Auxin response factors. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2007, 10, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilfoyle Tom J, Ulmasov T, Hagen, G. The ARF family of transcription factors and their role in plant hormone-responsive transcription. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 1998, 54, 619–627. [CrossRef]

- Juan Carlos, S.; Mariano, F.; Alejandro, A.; José, L. García-Martínez. Effect of gibberellin and auxin on parthenocarpic fruit growth induction in the cv Micro-Tom of tomato. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2007, 26, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Tyagi Akhilesh, K.; Sharma, A.K. Genome-wide analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family from tomato and analysis of their role in flower and fruit development. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2011, 285, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; OuYang, W.; Hou, X.; Xie, L.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide identification, isolation and expression analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Chen, L.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Lv, Z.; Yi, S.; Zhong, M.; Huang, C.; Jia, D.; Qu, X.; Xu, X. Three metabolic pathways are responsible for the accumulation and maintenance of high AsA content in kiwifruit (Actinidia eriantha). BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Xu, Q.; Allan Andrew, C.; Xu, X. L-Ascorbic acid metabolism and regulation in fruit crops. Plant physiology 2023, 192, 1684–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim Pyung, O.; Lee In, C.; Kim, J.; Kim Hyo, J.; Ryu Jong, S.; Woo Hye, R.; Nam Hong, G. Auxin response factor 2 (ARF2) plays a major role in regulating auxin-mediated leaf longevity. Journal of Experimental Botany 2010, 61, 1419–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yuan, C.; Li, H.; Lin, W.; Yang, Y.; Shen, C.; Zheng, X. Genome-wide identification and characterization of auxin response factor (ARF) family genes related to flower and fruit development in papaya (Carica papaya L.). BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Fu, W.; He, J. Chemical analysis of dietary constituents in Rosa roxburghii and Rosa sterilis fruits. Molecules 2016, 21, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dinh Thanh, T.; Li, D.; Shi, B.; Li, Y.; Cao, X.; Guo, L.; Pan, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Chen, X. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 3 integrates the functions of AGAMOUS and APETALA2 in floral meristem determinacy. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology 2014, 80, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; An, H.; Li, L. Genome survey sequencing for the characterization of the genetic background of Rosa roxburghii Tratt and leaf ascorbate metabolism genes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0147530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Sun, M.; Xu, R.; Shu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S. Genomewide identification and expression analysis of the ARF gene family in apple. Journal of Genetics 2014, 93, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otasek, D.; Morris John, H.; Bouças, J.; Pico Alexander, R.; Demchak, B. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biology 2019, 20, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park Jung-Eun, Park Ju-Young, Kim Youn-Sung, Staswick Paul, E.; Jeon, J.; Yun, J.; Kim Sun-Young, Kim, J.; Lee Yong-Hwan, Park Chung-Mo. Gh3-mediated auxin homeostasis links growth regulation with stress adaptation response in Arabidopsis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 10036–10046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson Andrew H, Bowers John E, Chapman, B.A. Ancient polyploidization predating divergence of the cereals, and its consequences for comparative genomics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 9903–9908. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Xue, Q.; Shu, P.; Xu, W.; Du, X.; Wu, M.; Liu, K.; Pirrello, J.; Bouzayen, M.; Hong, Y.; Liu, M. Bifunctional transcription factors SlERF.H5 and H7 activate cell wall and repress gibberellin biosynthesis genes in tomato via a conserved motif. Developmental Cell 2024, 59, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Fang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, L. Genome–wide identification and expression analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in Longan (Dimocarpus longan L.). Plants 2020, 9, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Yue, R.; Sun, T.; Zhang, L.; Xu, L.; Tie, S.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of auxin response factor gene family in Medicago truncatula. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N. Ascorbic acid metabolism and functions: a comparison of plants and mammals. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2018, 122, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, R.; Page, D.; Gouble, B.; Garchery, C.; Zamir, D.; Causse, M. Tomato fruit ascorbic acid content is linked with monodehydroascorbate reductase activity and tolerance to chilling stress. Plant, Cell & Environment 2008, 31, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari Shiv, B.; Wang, X.; Gretchen, H.; Guilfoyle Tom, J. AUX/IAA proteins are active repressors, and their stability and activity are modulated by auxin. The Plant Cell 2001, 13, 2809–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriezen Wim, H.; Feron, R.; Maretto, F.; Keijman, J.; Mariani, C. Changes in tomato ovary transcriptome demonstrate complex hormonal regulation of fruit set. The New Phytologist 2008, 17, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhan, J. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression analysis of the auxin response factor gene family in Vitis vinifera. Plant Cell Reports 2014, 33, 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Pei, K.; Fu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Tang, K.; Han, B.; Tao, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the auxin response factors (ARF) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa). Gene 2007, 394, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shi, F.; Dong, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2018, 18, 1587–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmoth Jill, C.; Wang, S.; Tiwari Shiv B, Joshi Atul D, Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle Thomas J, Alonso Jose M, Ecker Joseph R, Reed, J.; W. NPH4/ARF7 and ARF19 promote leaf expansion and auxin-induced lateral root formation. The Plant Journal 2010, 43, 118–130.

- Wu, J.; Wang, F.; Cheng, L.; Kong, F.; Peng, Z.; Liu, S.; Yu, X.; Lu, G. Identification, isolation and expression analysis of auxin response factor (ARF) genes in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant cell reports 2011, 30, 2059–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, H.; Pudake, R.N.; Guo, G.; Xing, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Ni, Z. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in maize. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, J.; Huang, X.; Zhou, C.; Li, L.; Fan, M. Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals Pollution for Rosa sterilis and Soil from Planting Bases Located in Karst Areas of Guizhou Province. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2014, 700, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Xu, L. ARF family identification in Tamarix chinensis reveals the salt responsive expression of TcARF6 targeted by miR167. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Mao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H. FveARF2 negatively regulates fruit ripening and quality in strawberry. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 1023739–1023739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okushima, Y.; Fukaki, H.; Onoda, M.; Theologis, A.; Tasaka, M. ARF7 and ARF19 Regulate Lateral Root Formation via Direct Activation of LBD/ASL Genes inArabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoko, O.; Overvoorde Paul, J.; Arima, K.; Alonso Jose, M.; Chan, A.; Chang, C.; Ecker Joseph, R.; Hughes, B.; Lui, A.; Nguyen, D.; Onodera, C.; Quach, H.; Smith, A.; Yu, G.; Theologis, A. Functional genomic analysis of the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR gene family members in Arabidopsis thaliana: unique and overlapping functions of ARF7 and ARF19. The Plant Cell 2005, 17, 444–463. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Mei, L.; Wu, M.; Wei, W.; Shan, W.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, F.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, W.; Miao, M.; Lu, W.; Li, Z.; Deng, W. SlARF10, an auxin response factor, is involved in chlorophyll and sugar accumulation during tomato fruit development. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69, 5507–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xu, X.; Gong, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wu, M.; Yan, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, F.; Hu, X.; Yang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Mei, L.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, C.; Lu, W.; Li, Z.; Deng, W. Auxin response factor 6A regulates photosynthesis, sugar accumulation, and fruit development in tomato. Horticulture Research 2019, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.; Lu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Lyu, T.; Li, X.; Bu, H.; Liu, W.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, H.; Wang, A. Auxin-activated MdARF5 induces the expression of ethylene biosynthetic genes to initiate apple fruit ripening. The New Phytologist 2020, 226, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cao, N.; Dong, C.; Shang, Q. Genome-wide identification and expression of ARF gene family during adventitious root development in hot pepper (Capsicum annuum). Horticultural Plant Journal 2017, 3, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, W.; Xie, R.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Yuan, C.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, L.; Liu, K. CpARF2 and CpEIL1 interact to mediate auxin-ethylene interaction and regulate fruit ripening in papaya. The Plant Journal 2020, 103, 1318–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Schenke, D.; Miao, Y.; Cai, D. Investigation of the crosstalk between the flg22 and the UV-B-induced flavonol pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant, Cell & Environment 2017, 40, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, D.; Liu, H.; Gan, P.; Ma, S.; Liang, H.; Yu, J.; Li, P.; Jiang, T.; Sahu Sunil, K.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Qiu, X.; Shao, W.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Guang, X.; He, C. Chromosomal-scale genomes of two Rosa species provide insights into genome evolution and ascorbate accumulation. The Plant Journal 2023, 117, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouine, M.; Fu, Y.; Chateigner-Boutin Anne-Laure, Mila, I.; Frasse, P.; Wang, H.; Audran Corinne , Roustan Jean-Paul, Bouzayen, M. Characterizationof the tomato ARF gene family uncovers a multi–levels post-transcriptional regulation including alternative splicing. Plos One 2014, 9, e84203.

| Gene Name |

Gene ID |

CDS Size |

Chromosome Location |

Protein | ||

| Length(aa) | MW(KDa) | pI | ||||

| RrARF1 | Rr100998 | 3549 | Chr1 | 1182 | 132.8 | 6.15 |

| RrARF2 | Rr203848 | 2031 | Chr2 | 676 | 75.5 | 5.83 |

| RrARF3 | Rr204729 | 2799 | Chr2 | 932 | 102.6 | 5.25 |

| RrARF4 | Rr300761 | 2232 | Chr3 | 743 | 81.5 | 6.31 |

| RrARF5 | Rr301243 | 2598 | Chr3 | 865 | 95.3 | 6.09 |

| RrARF6 | Rr304962 | 2145 | Chr3 | 714 | 78.7 | 8.56 |

| RrARF7 | Rr400968 | 3384 | Chr4 | 1127 | 124.7 | 6.24 |

| RrARF8 | Rr500747 | 2019 | Chr5 | 672 | 74.6 | 6.23 |

| RrARF9 | Rr500973 | 2607 | Chr5 | 868 | 96.5 | 6.07 |

| RrARF10 | Rr503508 | 2016 | Chr5 | 671 | 74.4 | 6.10 |

| RrARF11 | Rr505360 | 1713 | Chr5 | 570 | 62.6 | 6.13 |

| RrARF12 | Rr601745 | 2112 | Chr6 | 703 | 77.3 | 6.57 |

| RrARF13 | Rr703521 | 2061 | Chr7 | 686 | 76.0 | 6.56 |

| RrARF14 | Rr703808 | 2025 | Chr7 | 674 | 74.4 | 6.54 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).